Abstract

Objective

Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from oily fish reduce blood pressure (BP) in hypertension. Previously, we demonstrated that hypertension is associated with marked alterations in sphingolipid biology and elevated ceramide-induced vasoconstriction. Here we investigated in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) whether fish oil improves endothelial function including reduced vascular contraction induced via the sphingolipid cascade, resulting in reduced BP.

Methods

Twelve-week-old SHRs were fed a control or fish oil-enriched diet during 12 weeks, and BP was recorded. Plasma sphingolipid levels were quantified by mass spectrometry and the response of isolated carotid arteries towards different stimuli was measured. Furthermore, erythrocyte membrane fatty acid composition, thromboxane A2 formation and cytokine secretion in ex-vivo lipopolysaccharide-stimulated thoracic aorta segments were determined.

Results

The fish oil diet reduced the mean arterial BP (P <0.001) and improved endothelial function, as indicated by a substantially increased relaxation potential towards ex-vivo methacholine exposure of the carotid arteries (P <0.001). The long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diet resulted in altered levels of specific (glucosyl)ceramide subspecies (P <0.05), reduced membrane arachidonic acid content (P <0.001) and decreased thromboxane concentrations in plasma (P <0.01). Concomitantly, the fish oil diet largely reduced ceramide-induced contractions (P <0.01), which are predominantly mediated by thromboxane. Furthermore, thromboxane A2 and interleukin-10 were reduced in supernatants of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated thoracic aorta of SHRs fed the fish oil diet while RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted) was enhanced. This may contribute to reduced vasoconstriction in vivo.

Conclusions

Dietary fish oil lowers BP in SHRs and improves endothelial function in association with suppression of sphingolipid-dependent vascular contraction.

Keywords: blood pressure, ceramide, endothelial function, fish oil, long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, sphingolipid, spontaneously hypertensive rat, thromboxane A2

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease and it is the strongest risk factor for mortality worldwide [1,2]. The prevalence of hypertension is rising and has reached pandemic proportions, affecting around 30% of the population [3]. Hypertension is associated with endothelial dysfunction, which is mainly defined by decreased vasodilatory potential, increased contractile factor release (e.g. thromboxane A2), and endothelial activation (e.g. cytokine release) [4–6].

Next to classical pharmaceutical interventions to reduce blood pressure (BP) in hypertensive patients, there is an increasing interest for nutraceuticals, or functional foods, as part of an advocated lifestyle intervention. Prehypertensive patients, predisposed to develop hypertension as a consequence of their genetic background, may benefit from this. Meta-analysis showed that the beneficial effects of fish consumption, rich in long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFAs), are particularly prevalent in high-risk populations [7]. Supplementation with n-3 LCPUFA at a relatively high dose (3–9 g/day) markedly lowered BP in moderately hypertensive patients [8,9]. A hypotensive effect on SBP, but not DBP, was demonstrated even at low n-3 LCPUFA doses [150 mg docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) + 30 mg eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)] [10]. However, not all studies demonstrate a hypotensive effect of n-3 LCPUFAs on BP [11]. Still, many of these studies did not assess the effect of fish oil on endothelial dysfunction, which contributes to elevated BP and a persistent risk of developing end-stage organ damage [12,13].

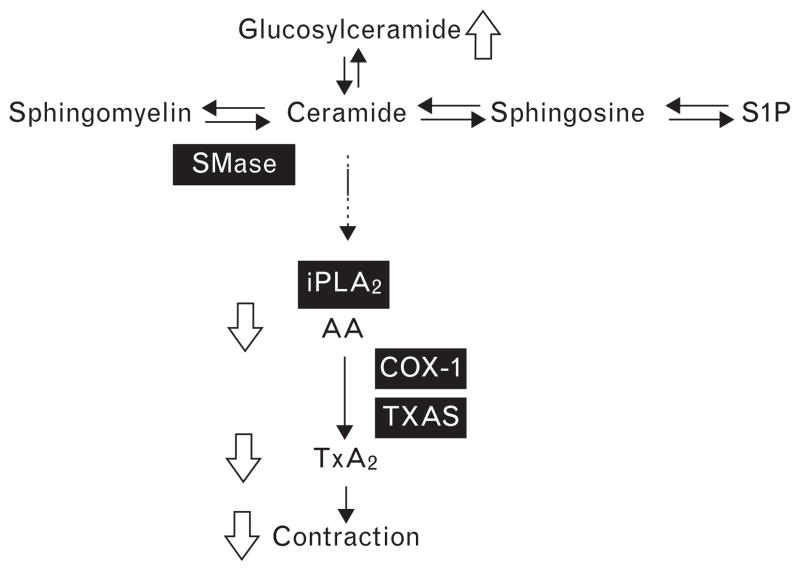

We have previously shown that hypertension is associated with altered sphingolipid levels in both hypertensive humans and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs). Vascular and plasma levels of the bioactive sphingolipid ceramide were higher in SHRs than normotensive rats. Furthermore, in hypertensive patients, plasma ceramide levels correlated positively with their BP. In addition, pharmacological elevation of ceramide using sphingomyelinase in isolated vessels of SHRs, but not normotensive rats, results in vasoconstriction due to the endothelium-dependent production of the contractile factor thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and increases BP in vivo [14]. High ceramide levels stimulate the activation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2), which releases arachidonic acid from the cell membrane. This n-6 LCPUFA serves as a substrate for cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and thromboxane synthase (TXAS) involved in TXA2 synthesis [15,16]. Expression of these enzymes is elevated in the SHR vasculature [14].

In this study, we assessed whether n-3 LCPUFAs from fish oil lower BP in SHRs by improving endothelial function in association with modulation of sphingolipid-initiated vascular contraction. Fish oil intake indeed reduced BP in SHRs and substantially improved endothelial function as determined ex vivo by methacholine-induced relaxation of carotid arteries. Furthermore, endothelial function restoration was associated with altered plasma ceramide and glucosylceramide subspecies, decreased erythrocyte cell membrane arachidonic acid content and lowered plasma TXA2 concentrations. In accordance, ceramide-induced contractions of carotid arteries were largely reduced in fish oil compared to control diet-fed SHRs. Ex-vivo mediator secretion by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated vessels was altered by the fish oil diet, which may relate to the reduction in arterial vascular tone in vivo. Therefore, a high n-3 LCPUFA diet may protect against the development or progression of essential hypertension by improving endothelial function, including suppression of sphingolipid-induced vascular contraction.

METHODS

Chemicals

Acetyl-β-methylcholine (methacholine), phenylephrine, bovine serum albumin (BSA, fatty acid free, low endotoxin) and EDTA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Neutral sphingomyelinase C (SMase C; from Staphylococcus aureus) from Enzo Life Sciences (Antwerp, Belgium), U46,619 from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) and LPS (purified Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS) from Invivogen (San Diego, California, USA). Furthermore, ketamine (Eurovet, Putten, The Netherlands), dexmedetomedine (Orion Pharma, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), atropine sulfate (PCH, Teva Pharmachemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands) and NaCl (Calbiochem, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were used. Other chemicals were from Merck Chemicals (Merck KGaA).

Animals

Animal use was performed in accordance with guidelines of the Animal Ethical Committee of the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Twelve-week-old male SHRs (Charles River, Maastricht, The Netherlands) were fed soy protein-based AIN-93G [17] containing 7% soybean oil (control diet), or a fish oil diet containing 3% soybean oil and 4% tuna oil (Research Diet Services, Wijk bij Duurstede, The Netherlands). Tuna oil (38.5% n-3 PUFA) was a kind gift from Bioriginal (Den Bommel, The Netherlands) and contained 27.8% DHA and 7% EPA. The ratio n-3-to-n-6 PUFA was 1 : 9.5 for the control diet, whereas this ratio was reduced to approximately 1 : 1 for the fish oil diet. The control diet contained 120 mg vitamin E/kg chow and the fish oil diet 155 mg/kg chow. Both diets are in the range of 30–200 mg vitamin E per kg of chow for normal rat diets [18] and are well above the minimal requirements for optimal endothelium function [19]. Rats were fed the diets during 12 weeks after which they were sacrificed.

Blood pressure measurements

Intra-arterial BP measurements were performed after rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with a mixture of ketamine (90 mg/kg), dexmedetomedine (0.125 mg/kg) and atropine sulfate (0.05 mg/kg). Furthermore, heparin (750 IU; Leo Pharma B.V., Weesp, The Netherlands) was injected i.p. to prevent blood coagulation. For this purpose, a PE-50 canula with PE-10-fused tip was inserted into the left femoral artery. Arterial pressure was recorded using LabChart data acquisition software (ADInstruments Ltd, Oxford, UK). When BP tracking stabilized, baseline values of BP were recorded and averaged over 10–15 min. Hereafter, plasma, organs and blood vessels were collected and processed. After tissue isolation, the rats were euthanized by exsanguination.

Arterial preparation and isometric force recording

Carotid arteries were isolated and placed in carbogen aerated (95% O2; 5% CO2) Krebs–Henseleit buffer (pH 7.4; in mmol/l: 118.5 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 25.0 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.1 KH2PO4, 0.025 EDTA and 5.6 glucose) at room temperature. After removing connective and adipose tissue, vessel segments were mounted in a multichannel wire myograph organ bath (M610; Danish Myo Technology A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) containing 37°C Krebs–Henseleit buffer under continuous carbogen aeration for isometric force measurement. Arterial lumen diameter was normalized according to Mulvany and Halpern and the experimental protocol was followed as previously described [20]. Briefly, vessels were contracted with the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (0.6 μmol/l) inducing a stable contraction more than 60% of the K+-induced contraction. Relaxation was induced by methacholine (10 μmol/l) to assess endothelial integrity. Subsequently, after 30 min washout, a third high K+-Krebs buffer contraction was performed. After 30 min washout, the enzyme SMase (0.1 U/ml) was applied to the organ baths to measure alterations in vasomotor tone during 1 h. In other arteries, concentration–response curves of methacholine during phenylephrine-induced contractions or the thromboxane analog U46,619 were generated.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry of plasma

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture using a 21G needle (BD Microlance 3) in a lithium heparin tube (4 ml Vacutainer Plasma Tube, BD). Blood samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 1600g at 4°C and plasma samples were stored at −70°C. Lipids were extracted from plasma according to Wijesinghe et al. [21] and Merrill et al. [22] with slight modifications as described in Spijkers et al. [14].

Fatty acid composition erythrocytes

After removal of plasma, erythrocytes were stored at −70°C until analysis. Erythrocyte lipids were extracted as described by Bligh and Dyer [23] and the membrane fatty acid composition was assessed using gas chromatography as previously described [24].

Mediator production

Thoracic aorta segments were stimulated ex vivo with 10 μg/ml LPS for 24 h in MEM199 (Gibo, Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). Supernatants were stored at −70°C. Cytokine release was assessed in supernatants by multiplex assay (Bio-Plex Pro, Rat 23-plex; Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands). Concentration of TXB2, the stable metabolite of TXA2, was measured in plasma samples and supernatants according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thromboxane B2 EIA kit; Cayman Chemical, Tallinn, Estonia).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using Student’s t test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test using Graphpad Prism Software version 5.0 (San Diego, California, USA). Concentration response curves were analyzed using nonlinear regression with variable slope to obtain EC50 values. Values of P less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The fish oil diet lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial relaxation potential to methacholine

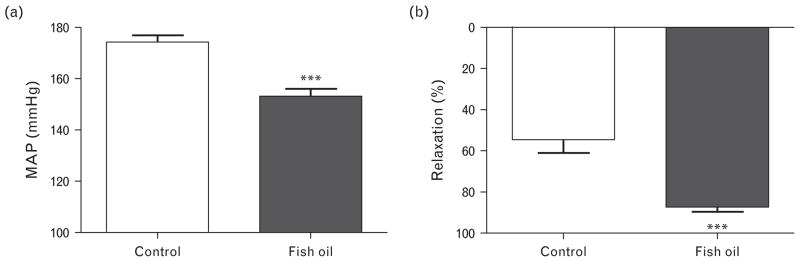

After 12 weeks of dietary intervention, the intra-arterially measured mean arterial BP in anesthetized SHRs was lower in fish oil diet-fed than control diet-fed rats (Fig. 1a). Supplementation with fish oil rich in n-3 LCPUFAs did not significantly affect rat body weight or heart and lung weight (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Blood pressure and endothelium-dependent arterial relaxing response in spontaneously hypertensive rats. (a) Mean arterial pressure (MAP) recorded in anesthetized rats after 12 weeks of dietary intervention. (b) Percentage relaxation of carotid artery after phenylephrine-induced contraction followed by a cumulative dose of methacholine of 30 μmol/l. Data presented as mean ± SEM, n =7–8, ***P <0.001 Student’s t test.

TABLE 1.

General characteristics of control and fish oil-fed spontaneously hypertensive rats

| Control diet (mean ±SEM) | Fish oil diet (mean ±SEM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rat body weight start (g) | 315 ±6 | 310 ±9 |

| Rat body weight 12 weeks (g) | 401 ±7 | 404 ±10 |

| Normalized heart weight (mg/g) | 3.9 ±0.1 | 3.8 ±0.1 |

| Normalized lung weight (mg/g) | 3.5 ±0.1 | 3.5 ±0.1 |

Heart and lung weight were normalized against rat body weight (n = 7–8).

Arteries of fish oil-fed SHRs displayed a significantly enhanced endothelium-dependent relaxation in response to a cumulative dose of methacholine compared to control diet-fed rats (Fig. 1b), whereas the EC50 was unaltered by feeding fish oil (pEC50: control 7.0 ± 0.1 versus fish oil 7.2 ± 0.1, n = 7–8). Contractile responses of isolated carotid artery rings to phenylephrine (0.6 μmol/l) were unaltered, whereas the smooth muscle contractile response to K+ (100 mmol/l) was slightly enhanced in vessels of SHRs fed the fish oil compared to the control diet (data not shown).

Dietary fish oil alters fatty acid composition of plasma ceramide and glucosylceramide

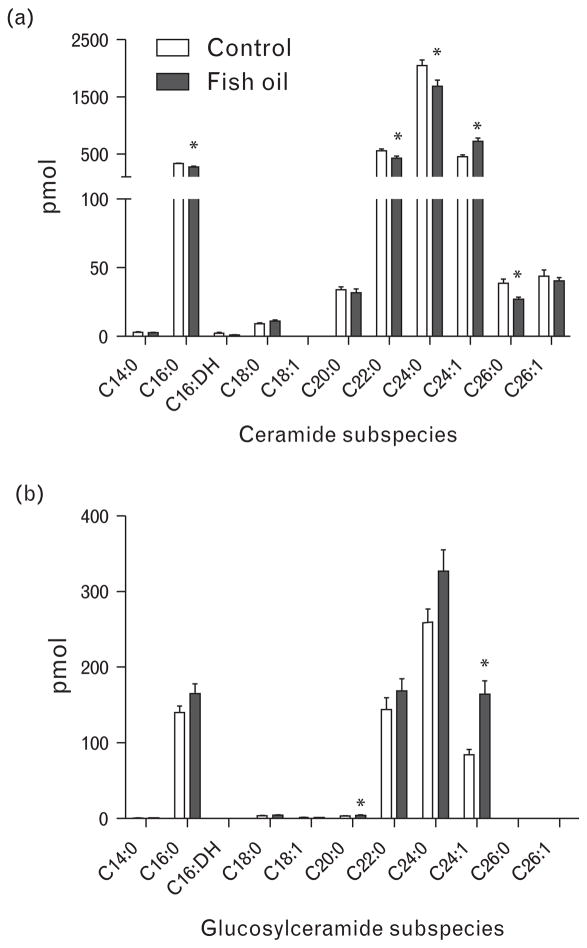

Lipidomic analysis of plasma samples demonstrated that the ceramide subspecies C16:0, C22:0, C24:0 and C26:0 were significantly decreased after fish oil supplementation, with only C24:1 ceramide levels elevated (Fig. 2a). The total ceramide content (cumulative levels of all acyl chain lengths) was not altered by these changes. In addition, elevated levels of C20:0 and C24:1 glucosylceramide were detected in plasma of fish oil-fed SHRs (Fig. 2b), resulting in a 30% increase in total glucosylceramide levels.

FIGURE 2.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry measurements of plasma sphingolipid content in control and fish oil-fed spontaneously hypertensive rats. Quantification of the spectrum of single subspecies of (a) ceramide and (b) glucosylceramide. Data presented as mean ±SEM, n =7–8, *P <0.05 Student’s t test. DH, dihydroceramide.

Exchange of arachidonic acid with docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in spontaneously hypertensive rat erythrocyte membranes after fish oil diet

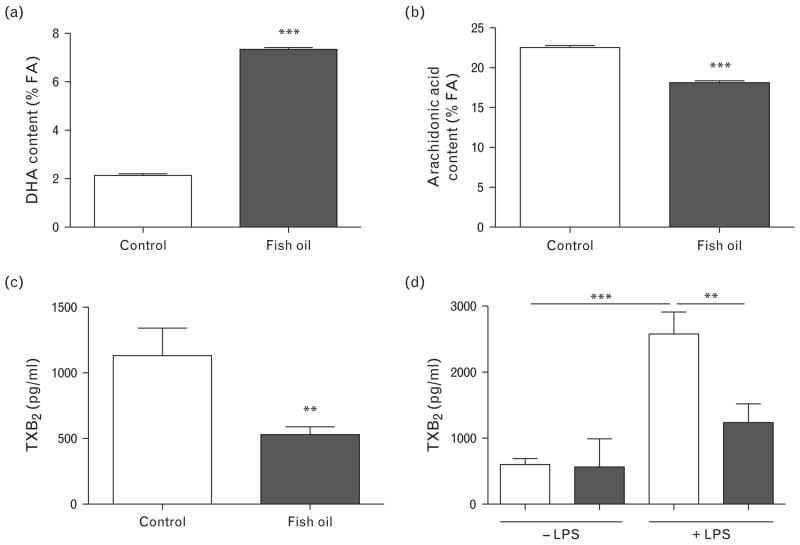

Ceramide stimulates the release of arachidonic acid from the cell membrane by activation of iPLA2. Arachidonic acid serves as a substrate for the synthesis of TXA2. Substitution of arachidonic acid by n-3 LCPUFAs DHA and EPA in the cell membrane reduces TXA2 formation and therefore vasoconstriction. Fish oil supplementation enhanced the DHA content of erythrocyte cell membranes by more than three-fold as compared with control diet-fed rat erythrocytes (Fig. 3a). In addition, the percentage of EPA in the membranes increased in the fish oil group (0.1 ±0.02% control versus 1.3 ±0.04% fish oil, n =7–8; P <0.001). The incorporation of n-3 LCPUFAs in the erythrocyte membrane occurred at the expense of n-6 PUFAs. Membrane arachidonic acid content was reduced by 20% (Fig. 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Erythrocyte membrane fatty acid (FA) content and thromboxane B2 (TXB2) generation. Content of n-3 LCPUFA (a) DHA and n-6 LCPUFA (b) arachidonic acid in erythrocyte cell membranes of control and fish oil-fed spontaneously hypertensive rats. TXB2 content in (c) plasma and (d) supernatants of thoracic aorta ex-vivo stimulated with LPS for 24 h. Data presented as mean ±SEM, n =7–8, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001 Student’s t test. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test to analyze TXB2 in supernatants. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; n-3 LCPUFA, long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid; n-6 LCPUFA, long-chain n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid; TXB2, thromboxane B2.

Fish oil supplementation reduced thromboxane B2 concentrations in spontaneously hypertensive rat plasma and supernatants of thoracic aorta upon ex-vivo lipopolysaccharide stimulation

The concentration of circulating TXB2 (the stable metabolite of TXA2) in plasma of fish oil-fed SHRs was effectively reduced compared with the control group (Fig. 3c). Plasma TXB2 concentrations correlated positively with SBP (r =0.62, P <0.05) and mean arterial pressure (r =0.76, P <0.01). Furthermore, ex-vivo LPS stimulation of thoracic aorta segments of control diet-fed rats resulted in an increase in TXB2 in supernatants (Fig. 3d). This concentration was significantly reduced in the fish oil diet group.

Previously, enhanced expression of iPLA2, COX-1 and TXAS was demonstrated in SHR compared with Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rat vessels [14]. These enzymes are responsible for TXA2 synthesis. Fish oil supplementation did not alter expression of these enzymes in endothelium or smooth muscle cells as determined by immunohistochemistry (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/A334, which demonstrates expression of iPLA2, COX-1 and TXAS in carotid artery).

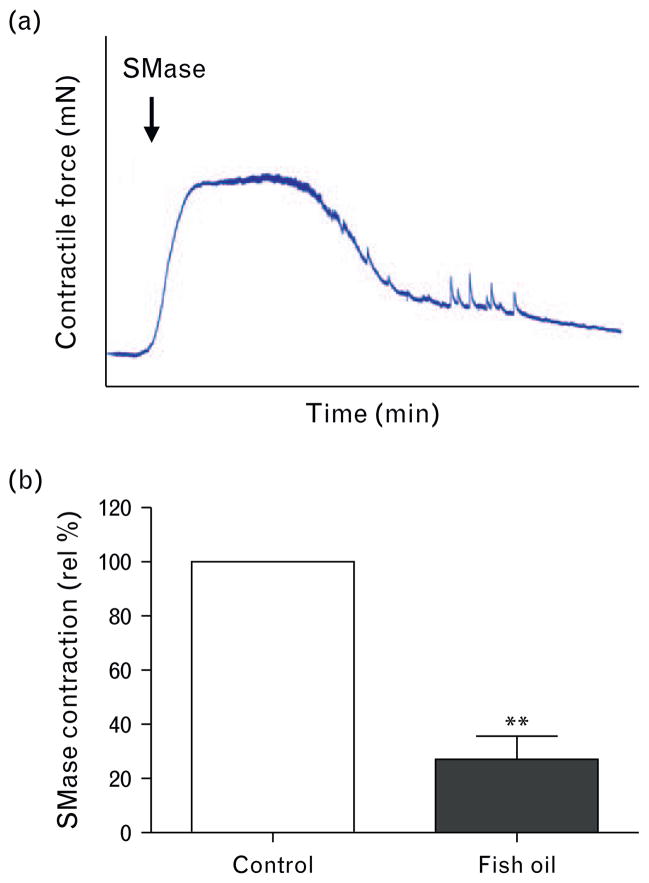

Fish oil diet reduces sphingomyelinase-induced contractions

Addition of exogeneous SMase to increase ceramide levels in isolated carotid arteries resulted in a marked endothelium-dependent contraction (Fig. 4a) in vessel segments of control diet-fed SHRs, which was reduced by more than 70% in the fish oil diet group segments (Fig. 4b). We have previously shown that these constrictions were mediated by the release of TXA2. The thromboxane receptor sensitivity remained unaltered by fish oil, as demonstrated by an equal dose–response curve of the thromboxane analog U46,619 in control SHR carotid artery segments (pEC50: 7.2 ± 0.2, Emax: 4.8 ± 0.1 mN/mm) compared with fish oil-fed rat artery segments (pEC50: 7.1 ± 0.2, Emax: 5.2 ± 0.2 mN/mm) (n =7–8; P >0.05).

FIGURE 4.

Sphingomyelinase-induced contractions in spontaneously hypertensive rat carotid artery. (a) Typical vasomotor tracing of rat carotid artery segments exposed to sphingomyelinase (SMase; 0.1 U/ml). (b) Maximal contractile responses to SMase as a relative percentage of the control group. Data presented as mean±SEM, n =7–8, **P <0.01, Student’s t test.

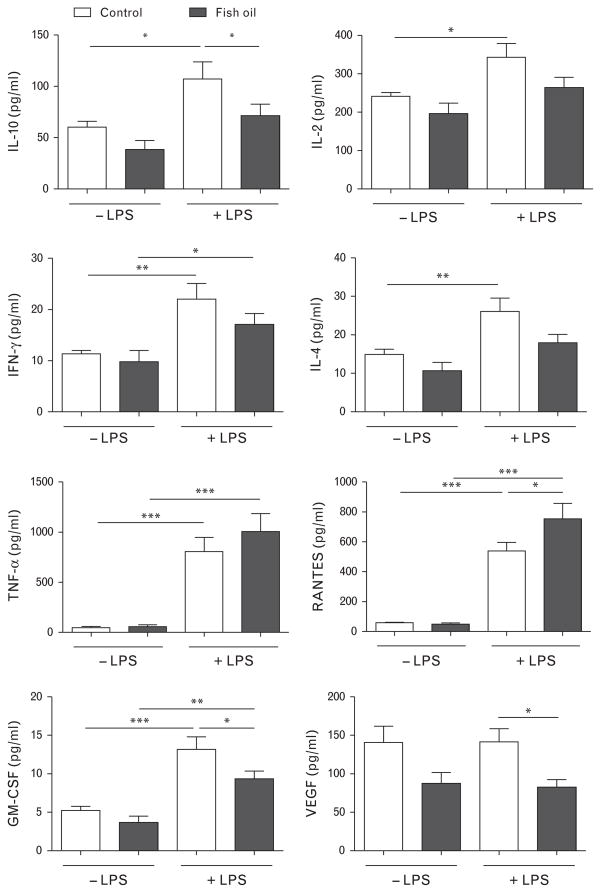

Dietary fish oil alters mediator secretion by ex-vivo lipopolysaccharide-stimulated thoracic aorta

Ex-vivo stimulation with LPS for 24 h induced the secretion of a plethora of mediators from thoracic aorta segments (Fig. 5). Aorta tissue from fish oil-fed SHRs secreted significantly less interleukin (IL)-10 after LPS stimulation when compared to control diet-fed rats. No significant effect of the fish oil diet was observed for the secretion of the other T-cell cytokines IL-2, interferon γ (IFN-γ) and IL-4. The amount of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in culture media from aorta tissue was not affected by the fish oil diet, whereas the production of the chemokine RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted) was significantly increased in LPS-stimulated vessels of fish oil-fed rats. On the contrary, the concentration of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was reduced in supernatants of LPS-treated aortas of fish oil-fed rats.

FIGURE 5.

Cytokine concentrations in supernatants of LPS-stimulated thoracic aorta segments ex vivo. Data presented as mean ±SEM, n =7–8, *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001 two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. ANOVA, analysis of variance; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN-γ, interferon γ; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the mechanism by which n-3 LCPUFA from fish oil contributes to BP-lowering in essential hypertensive rats. Here we show that fish oil indeed has substantial beneficial effects on BP and endothelial function. This may partially be achieved by a reduction in plasma ceramide subspecies which stimulates the formation of TXA2 through activation of iPLA2 and subsequent arachidonic acid liberation. In addition, the substitution of arachidonic acid by DHA and EPA in the cell membranes resulted in reduced TXA2 formation and attenuated ceramide-induced contraction of carotid arteries. Furthermore, reduced TXA2, IL-10 and enhanced RANTES secretion in supernatants of LPS-stimulated thoracic aorta of SHRs fed the fish oil diet may relate to reduced vasoconstriction in vivo.

Many studies have demonstrated a negative association between fish consumption and cardiovascular and/or overall morbidity and mortality [25–30]. In accordance, several studies have reported a BP-lowering effect by supplementation with EPA and/or DHA in both SHRs [31–34] and hypertensive patients [35–38], and this effect has been confirmed by meta-analyses [9,39]. Importantly, the study by Triboulot et al. [31] in 2001 indicated that fish oil did not reduce BP in WKY rats, and also in normotensive humans no effect of fish oil supplementation on BP was reported [40]. This suggests that fish oil reduces BP by targeting a mechanism primarily present in hypertensive patients. SHRs are genetically predisposed to develop hypertension and the pathophysiology resembles that of prehypertensive patients. These patients may be an interesting target group for dietary fish oil supplementation aiming to protect against the development or delay the progression of essential hypertension.

Here we demonstrate that a diet rich in fish oil was able to improve endothelium-dependent vasodilation, thus improving endothelial function. SHRs receiving a control diet demonstrated a lower maximal relaxation potential to methacholine than the fish oil group. This was likely due to increased endothelium-derived contractile mediators, of which thromboxane and prostacyclin are major contractile effectors [41]. Similar results were shown by the use of acetylcholine in thoracic aortic segments in SHRs [34]. Mori et al. [42] demonstrated enhanced vasodilator and reduced vasoconstrictor responses in the forearm microcirculation of overweight hyperlipidemic men using DHA, but not EPA, via endothelium-independent mechanisms. However, in the present study, endothelium-independent mechanisms most likely only play a minor role since the contractile responses upon exposure to K+ and the thromboxane analog U46,619, both endothelium-independent constrictors, were not reduced by the fish oil diet.

A possible mechanism which is responsible for BP elevation and endothelium-dependent vasoconstriction in hypertension involves the modulation of the sphingolipid system. We have previously shown that hypertension in both humans and SHRs is associated with elevated ceramide levels and marked ceramide-induced vascular contractions [8]. This indicates the contribution of sphingo-lipid-mediated blood vessel constriction not only in SHRs but also in human BP regulation. This study provides evidence on n-3 LCPUFAs being capable of provoking subtle alterations in sphingolipid biology in the SHRs. Although total ceramide levels were not altered by the diet, we observed some divergent changes in distinct ceramide subspecies. Furthermore, plasma glucosylceramide is reduced in SHRs compared with WKY rats (manuscript submitted), and this imbalance was partly restored by the fish oil diet. These interesting results warrant further investigation. In addition, the contraction of isolated carotid arteries to exogenous SMase was largely reduced in the fish oil group. Previously we have demonstrated that the contractile response to SMase, which generates ceramide from ubiquitously present membrane sphingomyelin, in isolated carotid arteries from SHRs is completely endothelium-dependent [14]. The reduced contraction of isolated carotid arteries to SMase in the fish oil group is most likely the result of decreased membrane arachidonic acid levels, resulting in reduced TXA2 generation after activation of iPLA2 by ceramide (see Fig. 6). Arachidonic acid is the predominant PUFA present in human lipids. A diet rich in n-3 LCPUFA lowers the membrane arachidonic acid content and consequently the production of arachidonic acid-derived eicosanoids [43,44]. Indeed, in SHR erythrocyte membranes, we demonstrated arachidonic acid as one of the predominant fatty acids, which was reduced by the fish oil diet, as demonstrated by others [33]. This substitution likely affects vascular substrate availability for COX to generate the contractile factor thromboxane in our experiments and it is feasible that a similar mechanism may improve endothelial cell function in the human situation as well.

FIGURE 6.

Suggested mechanism by which n-3 LCPUFA improve endothelial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats and contribute to decreased blood pressure. Functional effects of fish oil diet are indicated by hollow arrows. COX-1, cyclooxygenase 1; iPLA2, calcium-independent phospholipase 2; n-3 LCPUFA, long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; SMase, sphingomyelinase; TXA2, thromboxane A2; TXAS, thromboxane synthase.

We previously reported that the antihypertensive drug losartan decreased SMase-induced vasoconstriction by attenuating endothelial iPLA2 expression [45]. However, iPLA2, COX-1 and TXAS expression, responsible for ceramide-induced thromboxane production, appeared unaffected by the intervention with fish oil. Thus, reduced substrate availability is probably responsible for inhibition of the ceramide–thromboxane pathway. Indeed, the lower arachidonic acid membrane content was reflected by lower plasma thromboxane levels in SHRs fed with fish oil, like was shown in Yin et al. [34]. Several studies reported the ability of inflammatory stimuli to activate endogenous SMases to generate ceramide [46], possibly leading to enhanced thromboxane release [14]. In agreement with the latter, LPS treatment resulted in increased thromboxane release ex vivo, which was attenuated in the fish oil-fed group.

Not only was LPS-induced TXA2 release affected by the fish oil diet, secretion of other inflammatory mediators by the thoracic aorta was also altered. In hypertension, inflammatory cells are attracted to the activated endothelium and reside in the vascular wall. Inflammatory mediators released by endothelial and immune cells are characteristic for endothelial dysfunction. In patients with essential hypertension, pro-inflammatory cytokines were increased in LPS-stimulated whole blood [47]. Cytokines can directly modulate arterial vascular tone in isolated human vessels, for example, via the induction of SMases or endothelin-1 secretion, leading to vascular contraction [46,48]. Vascular endothelial cells express receptors for various cytokines including IL-10 and TNF-α, but not GM-CSF. TNF-α and IL-10 have been shown to promote endothelium-dependent vasoconstriction in arterial but not venous rings, whereas GM-CSF did not show an effect on vascular tone [48]. In this study, the IL-10 concentration in supernatants of LPS-stimulated thoracic aorta of SHRs fed the fish oil diet was reduced, which may relate to the in-vivo reduced vasoconstriction. Furthermore, other T-cell cytokines IL-2, IL-4 and IFN-γ showed a similar pattern, whereas TNF-α remained unaltered. High levels of circulating cytokines including IL-2 were previously associated with the development of hypertension, and reduced secretion of IL-2 was shown after fish oil intervention in SHRs, but not WKY rats [31]. In addition, a decrease in the LPS-induced production of the growth factors GM-CSF and VEGF was observed for fish oil-fed SHRs in this study, whereas the concentration of the chemokine RANTES was enhanced in media from LPS-treated aorta. Whereas RANTES is involved in the chemotaxis of monocytes, VEGF and GM-CSF have been described to activate monocytes which may contribute to the process of atherosclerosis [49–51]. Reduced levels of the latter two may therefore counter balance the possible pro-inflammatory effect of RANTES. Furthermore, previously, it has been shown that RANTES was down-regulated in SHRs, and this was suggested to induce hypertension [52,53].

In conclusion, these results present sphingolipid signaling alterations by fish oil as a mechanism that can prevent the rise in BP in SHRs, as depicted in Fig. 6. The intervention group presented less endothelial dysfunction as demonstrated by reduced ceramide-mediated contraction and enhanced relaxation to methacholine of carotid arteries, in association with reduced TXA2 and IL-10 and enhanced RANTES secretion by ex-vivo stimulated aortas. Since these factors are known to contribute to BP regulation in humans as well, these findings provide novel mechanistic insight into how n-3 LCPUFAs improve cardiovascular health.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Nutricia Research Foundation. This work was further supported by research grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (Career Development Award CDA1 to D.S.W., VA Merit Award BX001792 to C.E.C. and a Research Career Scientist Award to C.E.C.); from the National Institutes of Health via HL072925 (C.E.C.); NH1C06-RR17393 (to Virginia Commonwealth University for renovation); and from the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation via BSF#2011380 (C.E.C). Services and products in support of the research project were generated by the VCU Massey Cancer Center Lipidomics Shared Resource (Developing Core), supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059, as well as a shared resource grant (S10RR031535 to C.E.C.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- BP

blood pressure

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- i.p

intraperitoneal

- IFN-γ

interferon γ

- IL

interleukin

- iPLA2

calcium-independent phospholipase A2

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- n-3 LCPUFA

long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid

- RANTES

regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- SMase

sphingomyelinase

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- TXAS

thromboxane synthase

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WKY

Wistar–Kyoto

Footnotes

The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickering G. Hypertension. Definitions, natural histories and consequences. Am J Med. 1972;52:570–583. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J. Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2004;22:11–19. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spijkers LJ, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL. Sphingolipids and the orchestration of endothelium-derived vasoactive factors: when endothelial function demands greasing. Mol Cells. 2010;29:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Intengan HD, Schiffrin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: roles of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38:581–587. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.096249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S. Human endothelial dysfunction: EDCFs. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:1015–1023. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marckmann P, Gronbaek M. Fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality. A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:585–590. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knapp HR. Omega-3 fatty acids, endogenous prostaglandins, and blood pressure regulation in humans. Nutr Rev. 1989;47:301–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1989.tb02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris MC, Sacks F, Rosner B. Does fish oil lower blood pressure? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Circulation. 1993;88:523–533. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vericel E, Calzada C, Chapuy P, Lagarde M. The influence of low intake of n-3 fatty acids on platelets in elderly people. Atherosclerosis. 1999;147:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobiac L, Nestel PJ, Wing LM, Howe PR. Effects of dietary sodium restriction and fish oil supplements on blood pressure in the elderly. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1991;18:265–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1991.tb01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder L, Kiowski W, Buhler FR, Luscher TF. Indirect evidence for release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in human forearm circulation in vivo. Blunted response in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1990;81:1762–1767. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.6.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Salvetti A. Vasodilation to acetylcholine in primary and secondary forms of human hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;21:929–933. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spijkers LJ, van den Akker RF, Janssen BJ, Debets JJ, De Mey JG, Stroes ES, et al. Hypertension is associated with marked alterations in sphingolipid biology: a potential role for ceramide. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altiere RJ, Kiritsy-Roy JA, Catravas JD. Acetylcholine-induced contractions in isolated rabbit pulmonary arteries: role of thromboxane A2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;236:535–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller VM, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-dependent contractions to arachidonic acid are mediated by products of cyclooxygenase. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H432–H437. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.4.H432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC., Jr AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehr HA, Vajkoczy P, Menger MD, Arfors KE. Do vitamin E supplements in diets for laboratory animals jeopardize findings in animal models of disease? Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:472–481. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhein S, Kabat A, Olbrich A, Rosen P, Schroder H, Mohr FW. Effect of chronic treatment with vitamin E on endothelial dysfunction in a type I in vivo diabetes mellitus model and in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:114–122. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.045740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ Res. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wijesinghe DS, Allegood JC, Gentile LB, Fox TE, Kester M, Chalfant CE. Use of high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry for the analysis of ceramide-1-phosphate levels. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:641–651. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrill AH, Jr, Sullards MC, Allegood JC, Kelly S, Wang E. Sphingolipidomics: high-throughput, structure-specific, and quantitative analysis of sphingolipids by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 2005;36:207–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levant B, Ozias MK, Carlson SE. Diet (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid content and parity affect liver and erythrocyte phospholipid fatty acid composition in female rats. J Nutr. 2007;137:2425–2430. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kromhout D, Bosschieter EB, de Lezenne Coulander C. The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1205–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198505093121901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norell SE, Ahlbom A, Feychting M, Pedersen NL. Fish consumption and mortality from coronary heart disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6544.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daviglus ML, Stamler J, Orencia AJ, Dyer AR, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Fish consumption and the 30-year risk of fatal myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1046–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert CM, Hennekens CH, O’Donnell CJ, Ajani UA, Carey VJ, Willett WC, et al. Fish consumption and risk of sudden cardiac death. JAMA. 1998;279:23–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siscovick DS, Raghunathan T, King I, Weinmann S, Bovbjerg VE, Kushi L, et al. Dietary intake of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:208S–212S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.208S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, Rogers S, Holliday RM, Sweetnam PM, et al. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART) Lancet. 1989;2:757–761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Triboulot C, Hichami A, Denys A, Khan NA. Dietary (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids exert antihypertensive effects by modulating calcium signaling in T cells of rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:2364–2369. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.9.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dlugosova K, Okruhlicova L, Mitasikova M, Sotnikova R, Bernatova I, Weismann P, et al. Modulation of connexin-43 by omega-3 fatty acids in the aorta of old spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellenger-Germain S, Poisson JP, Narce M. Antihypertensive effects of a dietary unsaturated FA mixture in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Lipids. 2002;37:561–567. doi: 10.1007/s11745-002-0933-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin K, Chu ZM, Beilin LJ. Blood pressure and vascular reactivity changes in spontaneously hypertensive rats fed fish oil. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:991–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenz R, Spengler U, Fischer S, Duhm J, Weber PC. Platelet function, thromboxane formation and blood pressure control during supplementation of the Western diet with cod liver oil. Circulation. 1983;67:504–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao DQ, Mori TA, Burke V, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ. Effects of dietary fish and weight reduction on ambulatory blood pressure in overweight hypertensives. Hypertension. 1998;32:710–717. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonaa KH, Bjerve KS, Straume B, Gram IT, Thelle D. Effect of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on blood pressure in hypertension. A population-based intervention trial from the Tromso study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:795–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003223221202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori TA, Bao DQ, Burke V, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ. Docosahexaenoic acid but not eicosapentaenoic acid lowers ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate in humans. Hypertension. 1999;34:253–260. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ, Grobbee DE, Donders AR, Kok FJ. Blood pressure response to fish oil supplementation: metaregression analysis of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1493–1499. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimsgaard S, Bonaa KH, Hansen JB, Myhre ES. Effects of highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on hemodynamics in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:52–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feletou M, Verbeuren TJ, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-dependent contractions in SHR: a tale of prostanoid TP and IP receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:563–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori TA, Watts GF, Burke V, Hilme E, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ. Differential effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on vascular reactivity of the forearm microcirculation in hyperlipidemic, overweight men. Circulation. 2000;102:1264–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Schacky C, Fischer S, Weber PC. Long-term effects of dietary marine omega-3 fatty acids upon plasma and cellular lipids, platelet function, and eicosanoid formation in humans. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1626–1631. doi: 10.1172/JCI112147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yaqoob P, Pala HS, Cortina-Borja M, Newsholme EA, Calder PC. Encapsulated fish oil enriched in alpha-tocopherol alters plasma phospholipid and mononuclear cell fatty acid compositions but not mononuclear cell functions. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30:260–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spijkers LJ, Janssen BJ, Nelissen J, Meens MJ, Wijesinghe D, Chalfant CE, et al. Antihypertensive treatment differentially affects vascular sphingolipid biology in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu B, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Sphingomyelinases in cell regulation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997;8:311–322. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peeters AC, Netea MG, Janssen MC, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW, Thien T. Pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with essential hypertension. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:31–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iversen PO, Nicolaysen A, Kvernebo K, Benestad HB, Nicolaysen G. Human cytokines modulate arterial vascular tone via endothelial receptors. Pflugers Arch. 1999;439:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s004249900149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barleon B, Sozzani S, Zhou D, Weich HA, Mantovani A, Marme D. Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood. 1996;87:3336–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stojakovic M, Krzesz R, Wagner AH, Hecker M. CD154-stimulated GM-CSF release by vascular smooth muscle cells elicits monocyte activation: role in atherogenesis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:1229–1238. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0225-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heil M, Clauss M, Suzuki K, Buschmann IR, Willuweit A, Fischer S, Schaper W. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates monocyte migration through endothelial monolayers via increased integrin expression. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:850–857. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yun YH, Kim HY, Do BS, Kim HS. Angiotensin II inhibits chemokine CCL5 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1313–1320. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gouraud SS, Waki H, Bhuiyan ME, Takagishi M, Cui H, Kohsaka A, et al. Down-regulation of chemokine Ccl5 gene expression in the NTS of SHR may be pro-hypertensive. J Hypertens. 2011;29:732–740. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328344224d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]