Abstract

Hydrogels formed from self-assembling peptides are finding use in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. Given the notorious difficulties associated with producing self-assembling peptides by recombinant expression, most are typically prepared by chemical synthesis. Herein, we report the design of a family of self-assembling β-hairpin peptides amenable to efficient production using an optimized bacterial expression system. Expressing peptides, EX1, EX2 and EX3 contain identical eight-residue amphiphilic β-strands connected by varying turn sequences that are responsible for ensuring chain reversal and the proper intramolecular folding and consequent self-assembly of the peptide into a hydrogel network under physiological conditions. EX1 was initially used to establish and optimize the bacterial expression system by which all the peptides could be eventually individually expressed. Expression clones were designed to allow exploration of possible fusion partners and investigate both enzymatic and chemical cleavage as means to liberate the target peptide. A systematic analysis of possible expression systems followed by fermentation optimization lead to a system in which all three peptides could be expressed as fusions with BAD-BH3, the BH3 domain of the proapoptotic BAD (Bcl-2 Associated Death) Protein. CNBr cleavage followed by purification afforded 50, 31, and 15 mg/L yields of pure EX1, EX2 and EX3, respectively. CD spectroscopy, TEM, and rheological analysis indicate that these peptides fold and assembled into well-defined fibrils that constitute hydrogels having shear-thin/recovery properties.

1. Introduction

Exploiting natural protein folds has proven useful in the design of self-assembled hydrogel networks. Peptides derived from the secondary structural units of globular proteins represent a rich source of building blocks for the construction of higher-order functional assemblies. β-strand[1–16], helical[17–19], β-hairpin[20–23] and sheet[24] secondary structural motifs have all found utility in the design of novel self-assembled biomaterials. Even very small peptides having only a few residues[25–29] and cyclic peptides[30–32] can assemble into complex architectures that support function.

Our lab has been developing shear-thin injectable gels from self-assembling β-hairpin peptides[33–47]. MAX8 is a twenty-residue peptide that when initially dissolved in aqueous solution at pH 7 and low ionic strength adopts an ensemble of random coil conformations rendering it fully soluble. The peptide contains seven lysine residues whose side chains are protonated under these solution conditions resulting in inter-residue charge repulsion, which favors the unfolded state of the peptide. However, intramolecular folding and consequent self-assembly of the peptide into a fibrillar network can be accomplished by increasing the solution pH to deprotonate some of the lysines or by simply increasing the ionic strength of the solution to screen the lysine-borne charge. In addition, increasing the solution temperature also promotes gelation by facilitating the desolvation of hydrophobic residues. Self-assembly results in the formation of a fibrillar network where each fibril is comprised of a bilayer of hairpins that have inter-molecularly hydrogen bonded along the long axis of a given fibril. The association of the hydrophobic faces of the hairpin amphiphiles mediates bilayer formation, Figure 1. During assembly, non-covalent branch points are formed in the fibril network, which serve as physical crosslinks that help define the mechanical properties of the gel. MAX8 gels display shear-thin/recovery behavior, which makes their delivery from simple syringe possible [36, 40, 45].

Figure 1.

Triggered folding and subsequent self-assembly of a β-hairpin resulting in the formation of a fibrillar hydrogel network.

Most self-assembling peptides are typically prepared by solid phase peptide synthesis[48]. This technique is rapid and amenable for small-scale batches. However, it can be limited by cost for scaled efforts and relatively low overall yields, especially if the peptide is purified to homogeneity. MAX8 is synthesized employing an amide solid support resin by Fmoc-based techniques, which results in a C-terminally amidated peptide and yields that hover around 10% after stringent purification.

Recombinant production is an alternative method that employs a host organism’s machinery for peptide synthesis. Once optimized, fermentation represents a scalable, more cost-effective means to produce material-forming peptides. However, recombinant production of amphiphilic, self-assembling peptides is notoriously difficult and yields are typically low. With this said, work from the McPherson laboratory suggests that high yield production of self-assembling peptides is possible[49, 50]. They showed that self-assembling β-strands could be recombinantly produced in optimized media as fusion protein constructs which are shunted to inclusion bodies.

The recombinant production of amphiphilic self-assembling hairpins has not yet been reported and, with respect to the hairpins developed in our lab, is exceedingly challenging. This is due to their repetitive sequences, high hydrophobic content, and with respect to MAX8, it’s C-terminal amide and the inclusion of D-proline at position 10 within its turn region. Residues having D-stereochemistry about their Cα carbon are not accommodated by the ribosomal machinery of bacteria.

Herein, we use de novo design principles to replace the four-residue turn sequence of MAX8 with sequences having high turn propensity and importantly, that contain residues of only L-stereochemistry. Turn replacement as well as the incorporation of a C-terminal carboxylate affords three new peptides (EX1, EX2 and EX3) that are amenable to bacterial expression. We initially prepare EX1-3 by solid phase peptide synthesis to quickly assess their material forming properties before the arduous task of developing an optimal expression system. As will be shown, all three peptides self-assemble into well-defined gel networks capable of shear thin-recovery rheological behavior. Finally, expression vectors were designed to allow rapid identification of a low molecular weight fusion partner and cleavage method that, along with optimized fermentation procedures, afforded effective production of these peptides.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Fmoc-Val-Wang resin, Fmoc-Gly-Thr(ψMe,Mepro)-OH dipeptide and Fmoc-protected amino acids were purchased from Novabiochem. 1H-Benzotriazolium 1-[bis(dimethylamino) methylene]-5chloro-hexafluorophosphate (1-),3-oxide (HCTU) was obtained from Peptides International. Acetonitrile was purchased from EMD Chemicals. Trifluoroacetic acid was purchased from Acros Organics. Dithiothreitol (DTT), thioanisole, anisole, Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, LB agar, LB broth, SOC medium, yeast extract, tryptone, spectinomycin, chloramphenicol, ampicillin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. 1,2-Ethanedithiol was purchased from Fluka. Diethyl ether was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Triton X-100 was obtained from Alfa-Aesar. Laemmli sample buffer, Polypeptide Standard, Tris/Glycine/SDS buffer (10x) and Criterion 18% Tris-HCl precast gel were purchased from Bio-Rad. The miniprep plasmid DNA purification kit was purchased from QIAgen. DNA constructs were ordered from Genscript. BP and LR Clonase, subcloning efficiency DH5α, Rossetta 2 cells, SeeBlue Plus2 pre-stained standard, NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel 1.0 mm, NuPAGE MES-SDS running buffer (20X), SeeBlue Plus2 pre-stained standard and NuPAGE LDS sample buffer were purchased from Life Technologies. Carbenicillin was purchased from Teknova. pDonr253, pDest527, pDest532, pDest533, pDest546, pDest565 were kindly provided by Dominic Esposito (Protein Expression Laboratory, Leidos, NCI-Frederick). TevPep, MetPep, BadEX1, BadEX2 and BadEX3 genes were designed accordingly to be compatible for the Gateway cloning system by flanking attB sites at either ends and they were ordered from Genscript (See Supplemental Information). A cost analysis comparing the chemical synthesis and bacterial production of peptide EX1 is provided in the Supporting Information.

2.2 Solid phase peptide synthesis and purification

An automated ABI 433A peptide synthesizer was used to synthesize the peptides. Fmoc-based solid peptide chemistry with HCTU activation was performed. A trifluoroacetic acid: thioanisole: 1,2-ethanedithiol: anisole (90:5:3:2) cocktail under Argon atmosphere for 2 h was used to cleave the dried resin-bound peptides from the resin and for simultaneous side-chain deprotection. Precipitation by cold diethyl ether and lyophilization of crude peptides were followed by peptide purification that was carried out by reverse phase-HPLC at 40°C equipped with a semi-preparative Vydac C18 column. HPLC solvents A and B were 0.1% TFA in water and 0.1% TFA in 9:1 acetonitrile: water, respectively. For EX1 purification, a gradient was employed as 0% solvent B for 2 min, 0–10% solvent B over 10 min, 10–27% solvent B over 34 min and then 27–37% solvent B over 40 min. EX1 eluted at 28%B. For EX2 purification, a gradient was employed as 0% solvent B for 2 min, 0–15% solvent B over 13 min and then 15–35% solvent B over 40 min. EX2 eluted at 31%B. For EX3 purification, a gradient was employed as 0% solvent B for 1 min, 0–12% solvent B over 11 min, 12–25% solvent B over 26 min and then 25–35% solvent B over 40 min. EX3 eluted at 27%B. LC-MS (ESI-positive mode) was performed to verify the purity of the lyophilized peptides. (See Supplemental Information)

2.3 Cloning and transformation

The Gateway cloning system (Invitogen) was used to construct the expression clones used for transformation. Initial entry clones were generated by BP recombination of either an attB-flanked TevPep gene (encoding the TEV protease site + EX1, see Table S12 for DNA sequence) or an attB-flanked MetPep gene (encoding the methionine cleavage site + EX1) with the attP-containing donor vector, pDonr253. Subsequent LR recombination reactions between the entry clones and destination vectors containing the various fusion partners afforded the expression clones used for the transformation step. For example, inserts were supplied with 4 μg of lyophilized pUC57 plasmid DNA dissolved in 20 μL of water. For BP and LR reactions, the manufacturer’s protocols were followed (Invitrogen). Briefly, 0.5 μL of 200 ng/μL pUC57 containing the TevPep insert, 1 μL of 120 ng/μL of pDONR253, 4.5 μL of TE buffer and 2 μL of BP clonase were mixed and left at room temperature for at least 1 h to generate the entry clones. Escherichia coli DH5α strain was used for cloning, and 1 μL of BP clonase reaction was transferred into 20 μL of pre-aliquoted subcloning efficiency DH5α cells thawed on ice. After 30 min incubation on ice, 30 sec at 42°C in a water bath and 2 min incubation on ice, 60 μL of SOC medium was added and cells were cultured in a shaker incubator at 37°C (250 rpm) for 1 h. From this culture, 50 μL was spread onto a LB agar plate with Spectinomycin (50 μg/mL) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Single colonies were picked and inoculated in 10 mL of LB media supplemented with Spectinomycin (50 μg/mL) and incubated overnight at 37°C (250 rpm), followed by plasmid DNA isolation using the Qiagen spin miniprep kit according to the manual. Plasmid DNA samples were submitted for sequencing and upon verification of the expected sequences, they were used for the LR cloning reaction.

For a 10 μL LR reaction, 50 ng of entry clone, 150 ng of destination vector that had the fusion partner of interest, 2 μL LR Clonase II and TE buffer pH 8 were mixed and left at room temperature for at least 1 h to generate the expression clones. From this LR clonase reaction, 1 μL was transferred into 20 μL of pre-aliquoted subcloning efficiency DH5α cells thawed on ice. Transformation, cell spreading on LB agar plates with ampicillin (100 μg/mL), single colony inoculation into 10 mL LB media with ampicillin (100 μg/mL), miniprep plasmid DNA isolation and sequence verification were performed as indicated in the previous paragraph, followed by transformation into the expression strain Rossetta 2 cells and cell spreading onto LB agar plates with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/mL). Glycerol stocks (8% glycerol) of Rossetta 2 cells with expression clones were prepared from overnight LB cultures inoculated with single colonies from LB agar plates. Expression clones corresponding to the BadBH3 domain were constructed in a similar fashion. For example, separate entry clones containing the BAD-EX1-3 genes (see Table S12) were used for LR recombination with a HisTag-containing destination vector to afford the expression clones shown in Figure 5A/B.

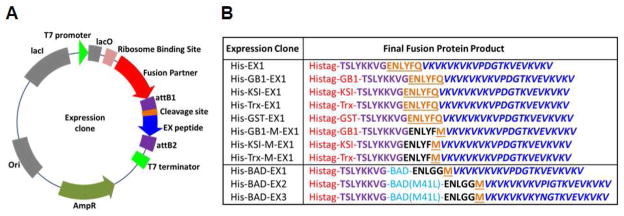

Figure 5.

(A) Representative plasmid map and (B) a list of peptide fusion constructs are shown. Fusion partners are shown in red, attB1 site amino acids in purple, cleavage sites in orange, and EX peptides in blue.

2.4 Bacterial culturing

For Rossetta 2 cell cultures, 100 μg/mL carbenicillin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol were added to the media. For pilot expression experiments, 25 mL of media was used in a 250 mL baffled flask. For larger scale experiments, 800 mL of LB media was used in 2.8 L baffled flasks, and 400 mL of AI or mAI media was used in 2.8 L baffled flasks.

LB media was prepared by dissolving 20 g/L LB broth media (Sigma) in distilled water followed by autoclaving. For starter cultures, 10 mL LB media with antibiotics was inoculated with the glycerol stock of Rossetta 2 cell (with the plasmid of interest) and incubated at 37°C (250 rpm) overnight. Fresh 25 mL LB media with antibiotics was then inoculated with 0.25 mL overnight culture and incubated at 37°C (250 rpm) until the OD600 reached 0.7–0.8. For large scale experiments, 30 mL starter culture was prepared with the glycerol stock of Rossetta 2 cell (with the plasmid of interest) as outlined above. To 800 mL LB media with antibiotics, 8 mL of overnight culture was added and incubated at 37°C (250 rpm) until the OD600 reached 0.7–0.8. A final concentration of 1 mM IPTG was used to induce the expression for 4 h at 37°C (250 rpm). After culturing, wet cell pellets obtained by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 10 min were stored at −80°C overnight prior to processing.

Auto-induction (AI) media was prepared according to Studier’s ZY-5052 media[51]: 10 g/L tryptone (Z) and 5 g/L yeast extract (Y); 0.5% glycerol, 0.05% glucose and 0.2% α-D-Lactose (5052); 25 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NH4Cl and 5 mM Na2SO4 (M), 2 mM MgSO4 and 0.2x trace elements. Modified AI (mAI) media was prepared similar to ZY-5052 media with the exception that it had 8 times of ZY and 4 times of 5052 in addition to the same amounts of M, MgSO4 and trace elements. For culturing in AI or mAI media, first 1 mL of LB media was inoculated with the glycerol stock and vortexed. Then 5 μL of the diluted glycerol stock was transferred and spread onto a LB agar plate with antibiotics for overnight incubation at 37°C. Three different colonies from the same plate were then individually inoculated into tubes with 2 mL LB media supplemented with antibiotics, M, 1% glucose, 2 mM MgSO4 and 0.2x trace elements, and incubated at 37°C (300 rpm) for 6 h. The most turbid culture was chosen and 225 μL was inoculated into 450 mL of AI or mAI media in 2.8 L baffled flasks, and incubated at 37°C (300 rpm) for 64 h. After culturing, wet cell pellets obtained by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 10 min, were stored at −80°C overnight prior to processing.

2.5 Cell Lysis after pilot expression

For TevPep fusions, an amount of culture normalized at OD600=3 were centrifuged in a 1.5 mL tube at 13000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM Dextrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 30 U/μL Ready-Lyse (Epicentre) lysozyme solution) with 5 U Benzonase nuclease (Novagen) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. To this, 100 μL of lysis buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% deoxycholate) was then added and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Following centrifugation, soluble fractions were separated into new tubes and insoluble pellets were solubilized in 100 μL of 8 M urea. For pre-induction samples, 1 mL pre-induction cultures were centrifuged and cell pellets were resuspended in 20 μL Lysis buffer A for 5 min, then 20 μL Lysis buffer B was then added and vortexed.

For MetPep fusions, an amount of culture normalized at OD600=3 were centrifuged in a 1.5 mL tube at 13000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended in 250 μL of Lysis buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5x Bugbuster (Novagen), 1 mM EDTA, 1.5 mg Lysozyme (Sigma), 5 mM MgCl2) with 2.5 U Bezonase nuclease (Novagen) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The cell lysate was then centrifuged for 5 min at 13000 rpm and the soluble fraction was transferred into a new tube. To the insoluble fraction, 250 μL of 8 M Urea was added and vortexed as before.

2.6 SDS-PAGE analysis

For SDS-PAGE analysis of the pilot expression of TevPep fusions, 10 μL pre-induction, soluble and insoluble samples were mixed with 10 μL Laemmli sample buffer with 0.35 M DTT before being heated at 95°C for 3 min. In addition to the samples, 10 μL Polypeptide Standard diluted 20 times in Laemmli sample buffer with 0.35 M DTT, were loaded onto a Criterion 18% Tris-HCl precast gel and electrophoresed (200 V for 60 min).

For SDS-PAGE analysis of MetPep fusion expressions, 20 μL of soluble and insoluble samples were mixed with 10 μL NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (3x) with 0.35 M DTT and heated as above. The samples as well as 10 μL of SeeBlue Plus2 pre-stained standard were loaded onto a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel and electrophoresed (200 V for 35 min). Gels were stained with a solution of 50 mg/L Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and 3 mL/L glacial acetic acid in water.

2.7 Pellet wash and solubilization of BAD-EX fusions

Cell pellets (~1 g) stored at −80°C were thawed and 40 mL wash buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) and 0.5% Triton-X100 was added. Cells were resuspended by sonication (QSonica Q700, 1/2″ tip, 60% Amp, 90 sec) and kept on ice. The sample was centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 min and the soluble fraction was removed. The insoluble fraction was treated with 40 mL wash buffer and 0.5% TritonX-100 once more and then twice with 40 mL wash buffer only, with sonication and centrifugation steps in between each step. The washed cell pellet was solubilized by sonication at low pH. For the washed cell pellets of the BAD-EX1 fusion, 100 mL of 0.1% TFA was used and for that of BAD-EX2 and Bad-EX3 fusions, 100 mL of 1% TFA was used; cell pellets were sonicated (1/2″ tip, 70% Amp, 3 min) and centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 15 min. Soluble fractions were lyophilized.

2.8 CNBr cleavage and purification of recombinant EX peptides

Cleavage of BAD-EX fusions by CNBr was performed by adding 0.1 g/mL CNBr in 70% formic acid to the sample to a final concentration of 60 mg/mL. The flask was purged with Argon and kept in the dark for 3 h before being diluted 10x in 0.1% TFA in 1:3 acetonitrile:water and lyophilized.

The lyophilized samples were dissolved in 0.1% TFA (for rEX1) or 1% TFA (for rEX2 and rEX3), sonicated, centrifuged and purified by RP-HPLC (semi-preparative Vydac protein/peptide C18 column) at 40°C. For rEX1 purification, a linear gradient was employed: 0% solvent B for 1 min, 0–12% solvent B over 12 min, 12–26% solvent B over 28 min and then 26–36% solvent B over 40 min. For rEX2 purification, a linear gradient was employed: 0% solvent B for 1 min, 0–14% solvent B over 10 min, 14–29% solvent B over 30 min and then 29–39% solvent B over 40 min. For rEX3 purification, a linear gradient was employed: 0% solvent B for 1 min, 0–11% solvent B over 7 min, 11–26% solvent B over 30 min and then 26–36% solvent B over 40 min. All three peptides eluted at similar %B values as the chemically synthesized peptides. Lyophilized peptides were weighed and analyzed by LC-MS (ESI-positive mode) (See Supplemental Information).

2.9 Circular dichroism

An Aviv model 410 circular dichroism spectrometer was employed to determine the secondary structure of the peptides in 1 wt% gels. Concentrations of peptide solutions were determined by using a small volume of stock solution and measuring the absorbance at 220 nm in a 1cm path length cell (ε = 15750 cm−1 M−1 for 20 amino acid peptides and ε = 16537 cm−1 M−1 for 21 amino acid peptides). The ε220 value of 15750 cm−1 M−1 was experimentally determined via amino acid analysis previously for a peptide of identical length and similar amino acid composition[20]. The ε220 value for the 21-residue peptides was calculated to account for one additional residue (e.g. (15750 cm−1 M−1/20) × 21).

For CD of 1 wt% gels, lyophilized peptides were dissolved in chilled water to make 2 wt% solutions and mixed with chilled stock buffer (100 mM BTP, 300 mM NaCl pH 7.4) at equal volumes to yield a final concentration of 1 wt% peptide in 50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4 buffer. The resulting solution was immediately transferred to a 0.1 mm quartz cell. The cell was immediately placed into a 37°C pre-equilibrated chamber which induced gelation. Wavelength scans from 260 to 200 nm were collected after 1 hour at 37°C.

Mean residue ellipticity [θ] was calculated from the equation [θ] = θobs/(10lcr), where θobs is the measured ellipticity in millidegrees, l is the path length of the cell (centimeters), c is the concentration (molar), and r is the number of residues in the sequence.

2.10 Oscillatory Rheology

An AR-G2 Magnetic Bearing Rheometer (TA Instruments) with 25 mm or 8 mm diameter parallel plate geometry at a gap height of 0.5 mm was employed for dynamic time, frequency and strain sweep rheology experiments. A 2 wt% peptide stock solution was prepared by dissolving the lyophilized peptide in chilled water and mixed with an equal volume of chilled stock buffer of 100 mM BTP, 300 mM NaCl pH 7.4 to yield a final concentration of 1 wt% peptide in 50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4 buffer. This final solution was immediately transferred to the rheometer peltier plate at 5°C. The temperature was ramped from 5°C to 37°C in 100 sec to induce gelation. The dynamic time sweep experiment, which measures the evolution of storage (G′) and loss modulus (G″) with time, was performed for 1h. at constant strain (0.2%) and frequency (6 rad/s), Figure S9. Independent dynamic frequency sweep (0.1–100 rad/s at 0.2% strain) and strain sweep (0.1–100% strain at 6 rad/s) experiments were performed to confirm that the time sweep measurements were executed within the linear viscoelastic regime. To test the recovery of elastic properties of 1 wt% hydrogels, shear-thinning and recovery experiments were performed. 1 wt% samples were prepared the same way. Following the temperature ramp from 5°C to 37 °C in 100 s and 20 min at 37°C with constant frequency (6 rad/s) and strain (0.2%), the strain was increased to 1000% for 30 sec and then reduced back to 0.2%. Over the next 20 min, the recovery of the hydrogel was monitored by measuring G′ and G″ as a function of time.

2.11 Electron Microscopy

1 wt% peptide samples (50 μL total volume) in 50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4 buffer were prepared by mixing chilled 2 wt% peptide solution in water and chilled stock buffer of 100 mM BTP, 300 mM NaCl pH 7.4. Samples were placed in 37°C incubator for 1 hour and left at room temperature until the TEM experiments were performed.

A small amount of hydrogel was diluted in water 40X and mixed intensely. Then, 2 μL was transferred onto 200 mesh carbon coated copper grid and allowed to sit for 1 min. Filter paper was used to dry the remaining liquid on the grid. As a negative stain, 1% uranyl acetate was transferred onto the grid and filter paper was used to soak up extra stain. Imaging was performed immediately by using Hitachi H-7650 transmission electron microscopy at a voltage of 80 kV. ImageJ was used to measure the fibril widths.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Peptide Design and Hydrogel Forming Properties

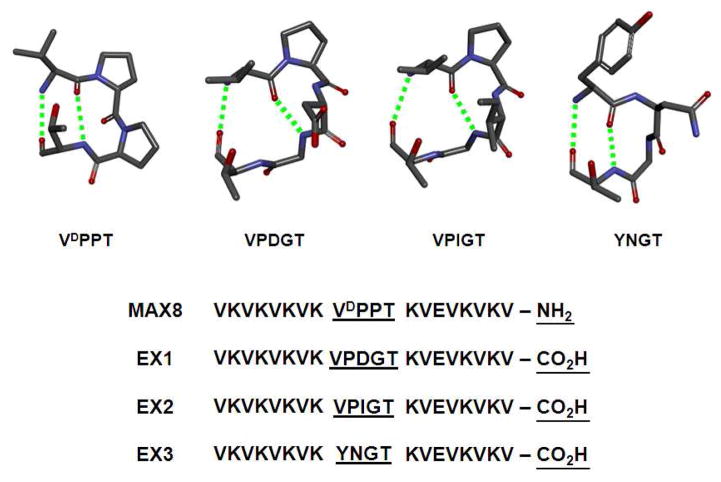

Several structural features of MAX8 preclude its preparation by bacterial expression, namely the D-proline contained within its turn region and the carboxamide functionality at its C-terminus. The four-residue turn of MAX8 (-VDPPT-) is central to its design, Figure 2. This sequence is designed to adopt a 2:2 type II′ β-turn where a full complement of backbone hydrogen bonds are formed between the valine and threonine residues at positions i and i+3 of the turn, respectively[20]. Each of the residues in the turn plays an important role in its folding. The valine residue contains a β-branched side chain that stabilizes a trans amide bond between it and the successive D-proline[52]. The D- and L-proline residues at positions i+1 and i+2 adopt dihedral angles that ensure reversal of the main chain when peptide folding is initiated[53]. The threonine at position i+4 is designed to stabilize the folded turn via hydrogen bond formation between its side chain alcohol and the main-chain carbonyl of the valine at position i (not shown in Figure)[54]. All of these residues collaborate to ensure the formation of a stable turn that, in part, defines the proper folding and assembly of the peptide. Thus, designing a new family of hairpins amenable to bacterial expression necessitates that the entire turn sequence be replaced and not simply the D-Pro of the original turn.

Figure 2.

Beta-turn structures and sequences of peptides MAX8 and EX1-3 are shown along with the hydrogen-bonding pattern of each turn. Design changes made to the parent MAX8 peptide are underlined.

Figure 2 shows the structures and sequences of three new turns and the corresponding peptides in which they are contained, namely EX1-3. Different turn sequences were incorporated to study their effect on folding, self-assembly, and hydrogel physical properties. This allows ill-behaved sequences to be ruled out for future bacterial expression studies. Each turn sequence contains all L-residues and is designed, based on literature precedence, to form a stable reverse turn. Peptide EX1 contains the five-residue turn –VPDGT-. This sequence is designed to adopt a 3:5 type 1 + G1 β-bulge turn, a motif commonly found in proteins[55]. In this turn, hydrogen bonds are formed between the amide of the valine and the carbonyl oxygen of the threonine as well as the valine’s carbonyl and the amide of the glycine[56]. This distinctive H-bond pattern is made possible by the formation of a classical type I turn centered at the –PD- dipeptide coupled to a β-bulge comprising the glycine and threonine residues, which adopt dihedral angles in αL and β Ramachandran space, respectively[56]. We specifically choose the residues –PDG- to occupy the central three positions of the turn (i+1, i+2 and i+3) based on their prevalence in naturally occurring proteins, for example 15-lipoxygenase (1LOX), and their use in the design of model hairpin peptides[57–59].

Peptide EX2 contains the same turn sequence except that the aspartate at position i+2 has been replaced with isoleucine. In EX1, the negatively charged aspartic acid side chain is positioned on the hydrophobic face of the amphiphilic β-hairpin. Replacing this polar side chain with the nonpolar side chain of isoleucine may stabilize the 3:5 type 1 + G1 β-bulge turn. Lastly, EX3 contains -YNGT-, which is designed to adopt a 2:2 type I′ β-turn. Type I′ turns are predominantly found in hairpin regions of proteins. This turn type has a similar hydrogen bonding pattern when compared to the original type II′ turn of MAX8, but adopts distinct main chain dihedral angles. The -YNGT- sequence was specifically incorporated based on the statistical preference of each of its amino acids to occupy the i through i+3 positions of type I′ turns found in proteins[54] in addition to the careful assessment of the folding propensity of the central -NG- unit in model β-hairpins[60–62]. The design of all three peptides (EX1-3) culminates with replacing the C-terminal amide functionality of its primary sequence with a carboxylate. Taken together, these designs principles yield peptides amenable to bacterial expression that should fold and assemble into well-defined fibrillar hydrogel networks.

3.2 Hydrogel Forming Properties of EX1-3

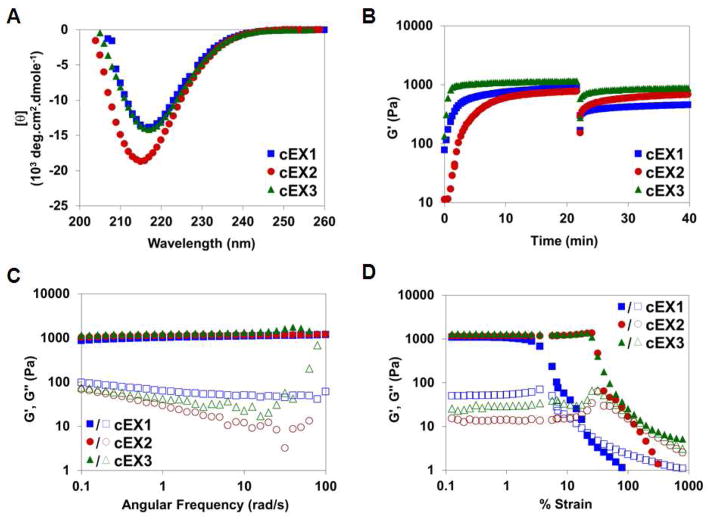

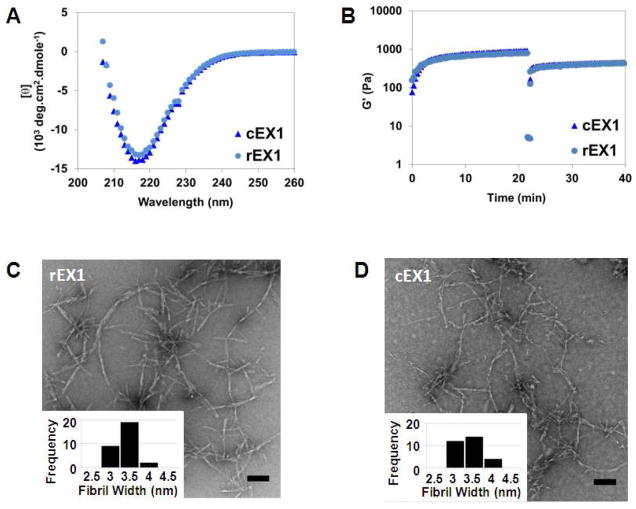

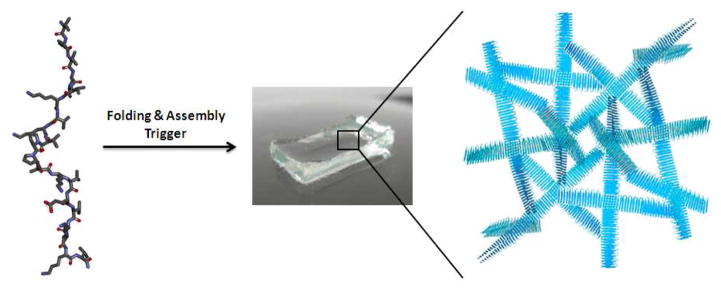

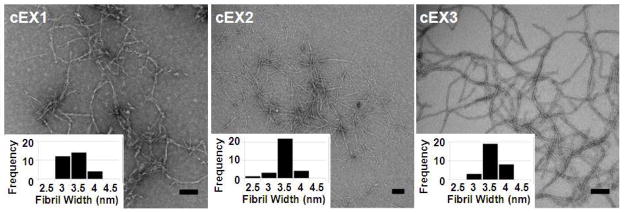

Each peptide was initially prepared via chemical synthesis to quickly assess their hydrogel forming properties before the difficult task of engineering a suitable expression system was embarked. Solid phase peptide synthesis employing Wang-Acid resin yielded peptides that were purified to near homogeneity (>98% purity, Figures S1-S3). Hydrogels can be formed by first dissolving chemically synthesized peptide (cEX1-3) in ice-chilled water at 2 wt%. Under these conditions the peptide remains unfolded. Folding and assembly is initiated by mixing an equal volume of chilled stock buffer and incubating the sample at 37°C. This results in the formation of a 1 wt% hydrogel (50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Figure 3a shows circular dichroism spectra of gels formed from cEX1-3. Spectra display distinct minima centered at ~ 218 nm, which indicates that the peptides fold and assemble into a gel network that is rich in β-sheet secondary structure. The local morphology of the network was confirmed to be fibrillar in nature by TEM. Figure 4 shows micrographs of fibrils formed by each of the peptides. All the peptide formed fibrils whose diameters are 3–4 nm, which corresponds to the length of a folded hairpin in the self-assembled state, Figure 1. Thus, the folded conformation of the peptide helps define the local morphology of the fibrils that constitute the gel.

Figure 3.

Analysis of secondary structure content and rheological properties of gels formed from chemically synthesized EX1-3. (A) Wavelength CD spectra of 1 wt% hydrogels (50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4) at 37°C. (B) Rheological shear-thin/recovery of 1 wt% hydrogels at 37°C. Initial time sweep (6 rad/s and 0.2 % strain) monitors gel formation for 20 min. after gelation was initiated. Then, application of 1000 % strain for 30 s, shear-thins the gel. Finally, a time sweep (6 rad/s, 0.2 % strain) monitors hydrogel recovery for an additional 20 min. (C) Dynamic frequency sweep (0.1–100 rad/s at 0.2% strain) and (D) dynamic strain sweep (0.1–100% strain at 6 rad/s) of 1 wt% hydrogels (50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4) at 37°C.

Figure 4.

TEM analysis of local morphology of fibrils formed by chemically synthesized peptides EX1-3. Insets show analysis of individual fibril widths (n = 30). Scale bar is 100 nm.

The time-dependent formation of the hydrogel and its ability to exhibit shear-thin/recovery properties was assessed in Figure 3b. For each peptide, gel formation was monitored rheologically by performing a dynamic time-sweep experiment that follows the evolution of the gel after folding and assembly are initiated. The data show that all three peptides form hydrogel networks within a minute that further stiffen with time, reaching similar plateau moduli of about 1000 Pa. cEX3 gels most quickly followed by cEX1 and lastly cEX2. After 20 minutes, 1000% strain was applied to the gels for 30 s to thin the materials. The immediate decrease in G′ indicates that the materials have thinned and are capable of flow. After the cessation of high strain, another time sweep at low strain (0.2 %, 6 rad/s) was performed to assess each gels’ ability to recover. The cEX2 and cEX3 gels recover about 90% of their initial mechanical rigidity, and the cEX1 about 50%. All three gels recover their mechanical rigidity within seconds. Gels displaying shear-thin/recovery behavior can be delivered by syringe further expanding their biomedical utility. The dynamic frequency sweep data in figure 3C shows that all three peptides form gels whose G′ values are invariant with frequency in the range of 0.1–100 rad/sec. The dynamic strain sweep experiments in Figure 3D indicate that the cEX2 and cEX3 gels yield at about 25% strain while the cEX1 gel yields at considerably lower strain (~ 6%).

The shear-thin/recovery and strain-sweep data suggest that the cEX1 gel behaves differently in that its less effective at recovering after being thinned and it yields at much lower values of strain. In fact, close inspection of the TEM images (Figure 4) show that the fibrils formed by cEX1 appear slightly more heterogenous in morphology when compared to cEX2 and cEX3 fibrils. This heterogeneity is also evident in the fibril width histogram (Figure 4, inset) where cEX1’s histogram is broader than either of the histograms for cEX2 or cEX3. Although speculative, cEX1 is the only peptide whose turn sequence places a negatively charged side chain (Asp) on the hydrophobic face of the hairpin. This point charge may not be well accommodated within the hydrophobic hairpin bilayer that defines the interior of a given fibril. As a result, the aspartic acid side chain may adopt a conformation that removes it from this hydrophobic environment and places it at the edge of the fibril. Here, the side chain would be solvent exposed and capable of making inter-fibril interactions that could lead to heterogeneity in fibril morphology and impact the rheological properties of the network. Although the cEX2 and cEX3 peptides performed slightly better than the cEX1 peptide, all three peptides were judged to be suitable for bacterial expression.

3.3 Vector Design and Pilot Expressions

We choose EX1 as our initial target for bacterial expression reasoning that an optimal expression strategy developed for this less well-behaved peptide should be able to accommodate both EX2 and EX3. The expression of small peptides can be difficult due to their susceptibility to proteolytic degradation. A general approach to overcome this possible limitation is to the express the peptide as a fusion with a larger protein[63]. In our initial studies we choose fusion partners that are well-studied and known to promote efficient expression in bacteria. The Gateway cloning system was used to prepare expression clones containing fusion partners upstream from EX1. Gateway destination vectors containing the various fusion partners upstream of the Att R recombination region were used to prepare expression clones, such as that shown in Figure 5A. Four different protein fusion partners were initially studied along with a control, which consisted of EX1 fused to a small hexahistidine tag (Histag). Each protein fusion also contained an N-terminal Histag, Figure 5B (entries 1–5). The first fusion, the B1 domain of protein G (GB1) from Streptococcus, is a 56-residue, highly soluble and thermally stable protein[64]. The next fusion comprised bacterial ketosteroid isomerase (KSI), a 125-residue oxidoreductase (~ 13 kDa, pI 5.3) that is extremely insoluble. KSI is typically used as a fusion partner to drive the formation of inclusion bodies[65]. Also used was thioredoxin (TrxA) from E. coli, a highly stable redox protein (~ 12 kDa, pI 4.7) that has been used extensively as a fusion partner[66]. Lastly, glutathione Stransferase (GST) is a 26 kDa (pI 5.3) highly soluble protein that is often used as a fusion partner to protect against intracellular proteolysis[67]. In the initial set of expression clones, a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease sequence (ENLYFQ) was included in between the fusion partner and EX1. Enzymatic cleavage C-terminal to the glutamine should liberate free EX1[68].

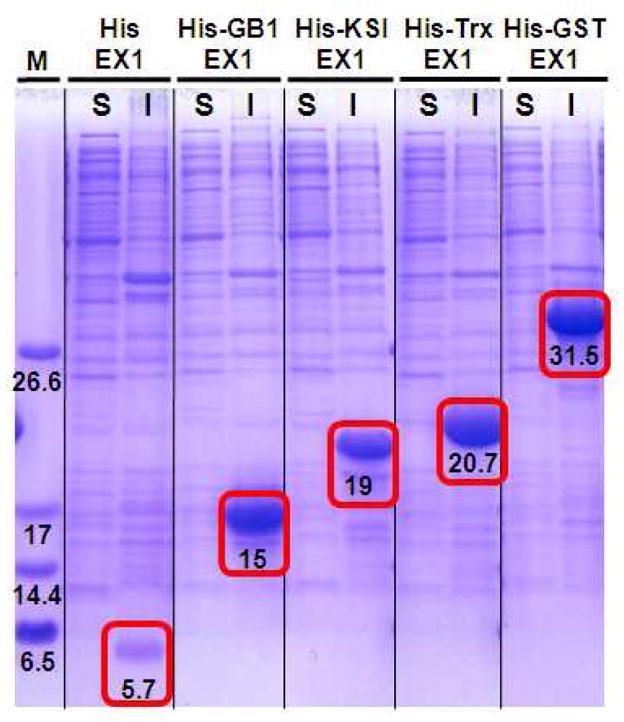

Expression clones were transformed into Rossetta 2 E. coli. for initial pilot expression studies. After fermentation, cells were harvested, lysed and the soluble and insoluble fractions analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Figure 6 shows that all the fusion proteins starting from the 5.7 kDa His-EX1 to the 31.5 kDa His-GST-EX1 were successfully expressed (highlighted by the red rectangles with expected MW values). The band corresponding to the control His-EX1 fusion is relatively faint suggesting that its expression was not as efficient as the other constructs. This may be due to its small size and consequent proteolytic susceptibility, demonstrating the need for a stabilizing fusion partner. Of note is the fact that all of the fusions were found in the insoluble fraction, even those expected to be highly soluble. This suggests that the EX1 peptide drives aggregation, shunting expressed protein-fusions to inclusion bodies. The peptide’s high hydrophobic content, amphiphilic character and propensity to self-assemble may be responsible for this activity. At any rate, larger batch culturing and immobilized metal affinity chromatography employing denaturing buffer afforded sufficient quantities of pure fusion protein (Figure S8) that could be used to optimize the TEV proteolysis step necessary to liberate EX1. Unfortunately, it was impossible to find denaturing buffer conditions that could simultaneously solubilize the EX1 fusion while maintaining the folded, functional state of the TEV protease. Thus, liberating EX1 from its fusion partner was not possible and another strategy was investigated.

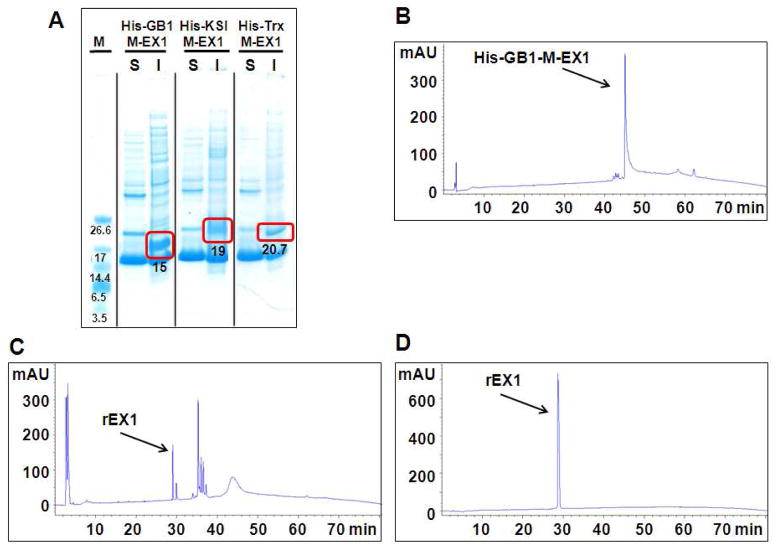

Figure 6.

Expression analysis of EX peptide fusion constructs by SDS-PAGE. Following cell lysis, soluble (S) and insoluble (I) fractions were analyzed along with molecular weight markers (M). Bands corresponding to the fusion constructs are found in the insoluble fractions and indicated by red boxes with the expected MWs.

Since EX1 is efficient at driving the aggregation of the fusion constructs, chemical cleavage was explored as a means to liberate free peptide under denaturing conditions. Thus, the TEV cleavage site was altered to include a methionine residue by mutating its C-terminal glutamine. Treatment of a given fusion with cyanogen bromide (CNBr) should liberate EX1. This approach was examined employing GB1, KSI, and Trx as the fusion partners, Figure 5B (entries 6–8). Following cloning, transformation, and pilot expression, SDS-PAGE analysis (Figure 7A) showed that all the fusion proteins were successfully expressed in the insoluble fraction. Band intensities suggest that the GB1 fusion expressed most efficiently and thus, this fusion alone was selected for further cleavage studies. Larger batch culturing afforded a cell pellet that could be solubilized in 8 M urea containing 0.1 % TFA. The TFA ensures protonation of EX1’s seven lysine residues, enhancing its solubility. Dialysis against 0.1 % TFA in water affords very pure His-GB1-M-EX1 fusion as assessed by RP-HPLC, Figure 7B. After lyophilization, the fusion can be solubilized with 70 % formic acid and cleaved via CNBr. Figure 7c shows a chromatogram of the cleavage reaction and liberation of EX1. Subsequent purification by RP-HPLC afforded pure recombinant rEX1 (Figure 7d) whose mass was validated by ESI-MS, Figure S4. The yield of HPLC purified rEX1 using this protocol was a moderate 4.6 mg/L. We next set out to improve on this yield by optimizing the fusion partner as well as the culturing conditions and the downstream processing of the peptide.

Figure 7.

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of methionine-containing EX1 fusion constructs His-GB1-M-EX1, His-KSI-M-EX1, and His-Trx-M-EX1. Fusions express in the insoluble fraction as indicated by the red boxes. (B) RP-HPLC chromatogram of the His-GB1-M-EX1 fusion and (C) crude rEX1 after CNBr cleavage. (D) Chromatogram of purified rEX1. All chromatograms collected using a gradient of 1% Std B per minute, monitored at 220 nm.

3.3 Design of a low molecular weight fusion partner for peptide EX1

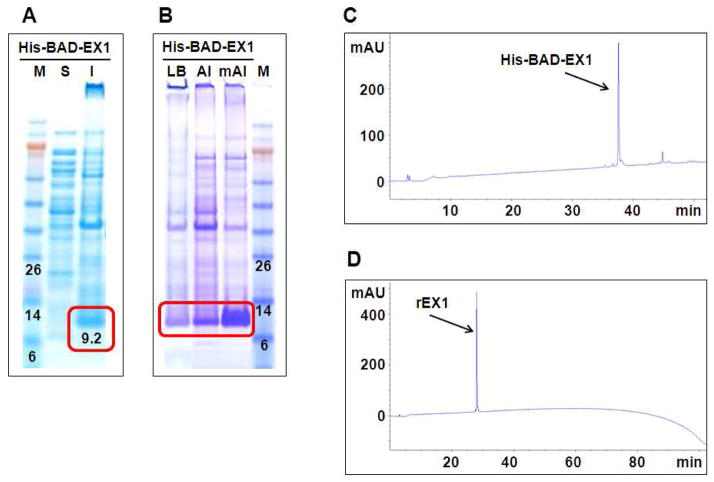

The theoretical yield of rEX1, in part, depends on the relative size (molecular weight) of its fusion partner. A peptide fusion containing a smaller partner yields more peptide on a weight basis. Although GB1 performed adequately, we investigated the possibility of replacing it with a smaller fusion that could be used for subsequent culture and processing optimization studies. The BH3 domain of the proapoptotic BAD (Bcl-2 Associated Death) protein is a small peptide with the propensity to form α-helical structure[69]. BAD-BH3 has a molecular weight of 3.2 kDa, about half the size of GB1, and is characterized by a pI ~ 8.6. A His-Bad-EX1 expression clone was prepared (Figure 5B, Table S12), which was transformed into Rossetta 2 E. coli. SDS-PAGE analysis of a pilot expression shows that the fusion can be found in the insoluble fraction. The relative staining intensity of the band suggests that His-Bad-EX1 is expressed in good yield, especially considering that a significant fraction of the fusion precipitated in the well of the gel (see upper most band in Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of His-BAD-EX1 showing the fusion in the insoluble fraction. (B) Comparison of expression levels using LB, auto-induction (AI) and modified AI medias (C) RP-HPLC chromatogram of the His-BAD-EX1 fusion and (D) chromatogram of purified rEX1 after CNBr cleavage. All chromatograms collected using a gradient of 1% Std B per minute, monitored at 220 nm.

3.4 Optimization of culturing conditions and downstream processing

For all the expression trials described thus far, standard LB media was used employing IPTG for induction. Added during the logarithmic growth phase, IPTG allows for the production of T7 polymerase, which binds to the T7 promoter region upstream of the gene of interest and facilitates its transcription. As an alternative, auto induction (AI) media can be used, in which the bacteria’s preference for carbon source determines the induction time. Here, glucose and lactose are present at the beginning of culture. The presence of glucose prevents the uptake of lactose. When glucose is depleted, lactose is transported into the cell and converted to allolactose, which then facilitates induction. The use of AI media allows the bacteria to define the induction time optimally and thus, can improve the yield of expressed protein. In addition to the AI media, a modified AI media (mAI), which contains an enhanced carbon source, was also assessed. We found that the use of mAI media afforded much higher cell densities (OD600 ~ 19) when compared to LB (OD600 ~ 3) and AI (OD600 ~ 11). Although it took longer to reach these high cell densities, the mAI media yielded the greatest cell mass and amount of protein harvested per cell mass. Figure 8B shows SDS page analysis of pilot expressions using LB, AI and mAI media. All three media support the expression of His-BAD-EX1, however, the relative staining intensities suggest that the mAI media is superior.

Expressing EX1 as a fusion with larger protein partners, such as GB1, afforded cell pellets whose solubilization necessitated the use of 8 M urea, which complicated the isolation of the fusion at a sufficient purity suitable for chemical cleavage. We find that the BAD-BH3 fusion has excellent solubility characteristics, which allows rapid isolation of pure EX1-fusion suitable for chemical cleavage. The following optimized protocol leads to the efficient recovery of pure EX1. Inclusion bodies, isolated from centrifugation, are sonicated and washed with buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) containing 0.5% Triton-X100. The detergent solubilizes bacterial protein while the 0.1 M NaCl ensures that the His-BAD-EX1 remains insoluble. Subsequent washing with buffer alone removes residual detergent from the pellet. The resulting pellet contains the fusion along with a small amount of cellular debris. Sonicating the pellet in 0.1 % TFA solubilizes the EX1-fusion, which can be separated from the debris via centrifugation. Lyophilization of the soluble fraction affords the fusion as a powder of suitable purity for chemical cleavage, Figure 8C. CNBr cleavage, followed by RP-HPLC purification affords pure rEX1 as shown in Figure 8D. Using this protocol, a purified yield of 50 mg of EX1 per liter of culture can be realized.

Similar methodology can be extended to the other β-hairpin self-assembling peptides, EX2 and EX3. Expression clones for these two peptides were prepared with a slight modification, Figure 5B. Namely, a methionine residue at position 41 of the BAD-BH3 helical domain was mutated to leucine to ensure that chemical cleavage only take place at the intended methionine, which is N-terminal to the EX peptide. Leucine was used because of its high helical propensity which should further stabilize the secondary structure of the BAD-BH3 domain. Expression clones containing His-BAD-EX2 and His-BAD-EX3 were transformed into Rossetta 2 E. coli, which ultimately produced 31 mg and 15 mg of rEX2 and rEX3 per liter, respectively. It should be noted that EX2 and EX3 are slightly more hydrophobic in character. As such 1 % TFA was needed to solubilize their pellets as opposed to the 0.1 % TFA needed to solubilize the EX1 pellet. At any rate, the methodology described herein is general and able to accommodate the production of the self-assembling amphiphilic β-hairpin studies here and should be amenable to other classes of material forming peptides.

3.5 Comparison of chemically synthesized and recombinant peptides

Characterization of chemically synthesized and recombinant EX peptides and their corresponding gels was performed by CD, rheology and transmission electron microscopy to assess their secondary structure, elastic properties and local fibril morphologies, respectively. The properties of chemically versus recombinantly-made peptides (and their gels) should be similar since their characteristics should be independent of the method of production. Figure 9A shows wavelength CD spectra of 1wt% cEX1 and rEX1 peptide gels prepared at physiological conditions. Both spectra have similar line shape and characteristic minima around 218 nm, indicated that each peptide has folded and self-assembled, forming β-sheet rich structures. Figure 9B shows rheological evidence that each peptide is capable of forming gels of similar storage moduli that are capable of shear-thin/recovery. Lastly, the TEM micrographs in panels C and D show that each peptide assembles into fibrils having similar local morphologies, with fibril widths of ~ 3.5 nm which corresponds to the length of a folded hairpin in the self-assembled state. A similar analysis was performed comparing cEX2 and rEX2 as well as cEX3 and rEX3 (Figures S9 and S11). These data, along with that in Figure 9 indicate that peptide prepared recombinantly behaves identical to that prepared by chemical synthesis.

Figure 9.

Comparative CD wavelength spectra (A) and rheological analysis (B) of 1 wt% hydrogels (50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4) at 37°C prepared from cEX1 and rEX1. TEM analysis of local morphology of fibrils formed by (C) rEX1 and (D) cEX1. Insets show analysis of individual fibril widths (n = 30). Scale bar is 100 nm.

4. Conclusion

A new family of β-hairpin peptide hydrogelators is described that are amenable to production by bacterial expression. Expressing peptides, EX1-3, were de novo designed using the parent peptide MAX8 as a template. MAX8 is known to undergo ordered self-assembly into a hydrogel network composed of β-sheet rich fibrils. However, MAX8 contains a D-residue in the turn region of its primary sequence as well as a carboxamidated C-terminus, both of which preclude its production in bacteria. Peptides EX1-3 contain re-engineered turn sequences composed solely of amino acids having L-stereochemistry as well as a carboxlated C-terminus. EX1 and EX2 contain turn designs that are based on consensus sequences know in the literature to a form 3:5 Type I + G1 bulge turn motif. EX3 contains a turn sequence designed to adopt a 2:2 type 1′ β-turn. Both turn types are used by naturally occurring proteins to ensure tight chain reversal, a hallmark of compactly folded globular proteins.

A family of expression clones were prepared that allow the rapid assessment of optimal fusion partners for the EX peptides. After investigating five different fusion partners, expressing the EX peptides as a fusion with the BH3 domain of the proapoptotic BAD (Bcl-2 Associated Death) protein proved most effective. Bacterial expression employing Rossetta 2 E. coli provided yields of 50, 31 and 15 mg/L of HPLC-purified EX1, 2 and 3, respectively. The amphiphilic sequence of the EX peptides directs expressed fusion to inclusion bodies, which aids in its isolation and purification. Chemical cleavage via CNBr liberates EX1-3 which is then purified by chromotography. CD Spectroscopy, rheology and TEM show that each peptide is capable of folding and assembling into a β-sheet rich fibril network affording hydrogels under physiological conditions. Resultant gels display shear-thin/recovery behavior enabling their delivery via syringe. These newly designed peptides, along with their optimized bacterial expression, provide a means to scalable production of peptide-based gels.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of chemically synthesized EX1

Figure S2: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of chemically synthesized EX2

Figure S3: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of chemically synthesized EX3

Figure S4: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of recombinant EX1

Figure S5: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of recombinant EX2

Figure S6: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of recombinant EX3

Figure S7: Dynamic time sweep experiment of 1wt% chemically synthesized EX peptides.

Figure S8: Gel electrophoresis of purified fusion proteins with enzymatic cleavage site

Figure S9: Comparison of secondary structure and elastic properties of 1wt% EX2 and EX3 gels formed by chemically synthesized (cEX) and recombinant (rEX) peptides. Wavelength CD spectra of EX2 (A) and EX3 (B) peptide gels. Dynamic time sweep experiments of EX2 (C) and EX3 (D) peptide gels. Shear-thin and recovery experiment of EX2 (E) and EX3 (F) peptide gels.

Figure S10: Dynamic (A) frequency and (B) strain sweep experiments of 1wt% rEX gels at 37°C (pH 7.4, 50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl).

Figure S11: TEM analysis of local fibril morphologies of rEX2 and rEX3 peptide gels. Insets show the individual fibril widths. Scale bar is 100 nm.

Table S1: DNA Sequences of designed genes

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dominic Esposito, Jacek Lubkowsky, Koreen Ramessar and Lauren Krumpe for helpful discussions.

Appendix

Supplementary Material: Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sakai H, Watanabe K, Asanomi Y, Kobayashi Y, Chuman Y, Shi LH, et al. Formation of functionalized nanowires by control of self-assembly using multiple modified amyloid peptides. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:4881–4887. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng Y, Taraban M, Yu YB. The effect of ionic strength on the mechanical, structural and transport properties of peptide hydrogels. Soft Matter. 2012;8:11723–11731. doi: 10.1039/C2SM26572A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumura S, Uemura S, Mihara H. Fabrication of nanofibers with uniform morphology by self-assembly of designed peptides. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:2789–2794. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu K, Jacob J, Thiyagarajan P, Conticello VP, Lynn DG. Exploiting amyloid fibril lamination for nanotube self-assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6391–6393. doi: 10.1021/ja0341642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang T, Xu CF, Liu Y, Liu Z, Wall JS, Zuo XB, et al. Structurally defined nanoscale sheets from self-assembly of collagen-mimetic peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4300–4308. doi: 10.1021/ja412867z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segman S, Lee MR, Vaiser V, Gellman SH, Rapaport H. Highly stable pleated-sheet secondary structure in assemblies of amphiphilic alpha/beta-peptides at the air-water interface. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:716–719. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanekamp RJ, DiMaio JTM, Bowerman CJ, Nilsson BL. Coassembly of enantiomeric amphipathic peptides into amyloid-inspired rippled beta-sheet fibrils. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5556–5559. doi: 10.1021/ja301642c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudra JS, Mishra S, Chong AS, Mitchell RA, Nardin EH, Nussenzweig V, et al. Self-assembled peptide nanofibers raising durable antibody responses against a malaria epitope. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6476–6484. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakota EL, Sensoy O, Ozgur B, Sayar M, Hartgerink JD. Self-assembling multidomain peptide fibers with aromatic cores. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1370–1378. doi: 10.1021/bm4000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoe U, Yang YL, Zhang SG. Self-assembly of nanodonut structure from a cone-shaped designer lipid-like peptide surfactant. Langmuir. 2009;25:4111–4114. doi: 10.1021/la8025232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies RPW, Aggeli A. Self-assembly of amphiphilic beta-sheet peptide tapes based on aliphatic side chains. J Pep Sci. 2011;17:107–114. doi: 10.1002/psc.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts D, Rochas C, Saiani A, Miller AF. Effect of peptide and guest charge on the structural, mechanical and release properties of beta-sheet forming peptides. Langmuir. 2012;28:16196–16206. doi: 10.1021/la303328p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowik D, Garcia-Hartjes J, Meijer JT, van Hest JCM. Tuning secondary structure and self-assembly of amphiphilic peptides. Langmuir. 2005;21:524–526. doi: 10.1021/la047578x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amit M, Cheng G, Hamley IW, Ashkenasy N. Conductance of amyloid beta based peptide filaments: Structure-function relations. Soft Matter. 2012;8:8690–8696. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin YA, Ou YC, Cheetham AG, Cui HG. Rational design of mmp degradable peptide-based supramolecular filaments. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:1419–1427. doi: 10.1021/bm500020j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geisler IM, Schneider JP. Evolution-based design of an injectable hydrogel. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:529–537. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher JM, Harniman RL, Barnes FRH, Boyle AL, Collins A, Mantell J, et al. Self-assembling cages from coiled-coil peptide modules. Science. 2013;340:595–599. doi: 10.1126/science.1233936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Leary LER, Fallas JA, Bakota EL, Kang MK, Hartgerink JD. Multi-hierarchical self-assembly of a collagen mimetic peptide from triple helix to nanofibre and hydrogel. Nat Chem. 2011;3:821–828. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stahl PJ, Yu SM. Encoding cell-instructive cues to peg-based hydrogels via triple helical peptide assembly. Soft Matter. 2012;8:10409–10418. doi: 10.1039/C2SM25903F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider JP, Pochan DJ, Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Pakstis L, Kretsinger J. Responsive hydrogels from the intramolecular folding and self-assembly of a designed peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15030–15037. doi: 10.1021/ja027993g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colfer S, Kelly JW, Powers ET. Factors governing the self-assembly of a beta-hairpin peptide at the air-water interface. Langmuir. 2003;19:1312–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Huang LX, Wang LJ, Hong YK, Sha YL. One-dimensional self-assembly of a rational designed beta-structure peptide. Biopolymers. 2007;86:23–31. doi: 10.1002/bip.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valery C, Paternostre M, Robert B, Gulik-Krzywicki T, Narayanan T, Dedieu JC, et al. Biomimetic organization: Octapeptide self-assembly into nanotubes of viral capsid-like dimension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10258–10262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1730609100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rughani RV, Salick DA, Lamm MS, Yucel T, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Folding, self-assembly, and bulk material properties of a de novo designed three-stranded beta-sheet hydrogel. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1295–1304. doi: 10.1021/bm900113z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler-Abramovich L, Aronov D, Beker P, Yevnin M, Stempler S, Buzhansky L, et al. Self-assembled arrays of peptide nanotubes by vapour deposition. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:849–854. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debnath S, Roy S, Ulijn RV. Peptide nanofibers with dynamic instability through nonequilibrium biocatalytic assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16789–16792. doi: 10.1021/ja4086353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma ML, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Gao P, Xu B. Aromatic-aromatic interactions induce the self-assembly of pentapeptidic derivatives in water to form nanofibers and supramolecular hydrogels. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2719–2728. doi: 10.1021/ja9088764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuran S, Razvag Y, Reches M. Coassembly of aromatic dipeptides into biomolecular necklaces. Acs Nano. 2012;6:9559–9566. doi: 10.1021/nn302983e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, McDonald TO, Adams DJ. Salt-induced hydrogels from functionalised-dipeptides. RSC Adv. 2013;3:8714–8720. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montero A, Gastaminza P, Law M, Cheng GF, Chisari FV, Ghadiri MR. Self-assembling peptide nanotubes with antiviral activity against hepatitis c virus. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1453–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richman M, Wilk S, Chemerovski M, Warmlander S, Wahlstrom A, Graslund A, et al. In vitro and mechanistic studies of an antiamyloidogenic self-assembled cyclic d,l-alpha-peptide architecture. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3474–3484. doi: 10.1021/ja310064v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gauthier D, Baillargeon P, Drouin M, Dory YL. Self-assembly of cyclic peptides into nanotubes and then into highly anisotropic crystalline materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4635. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4635::aid-anie4635>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giano MC, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Controlled biodegradation of self-assembling beta-hairpin peptide hydrogels by proteolysis with matrix metalloproteinase-13. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6471–6477. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinthuvanich C, Haines-Butterick LA, Nagy KJ, Schneider JP. Iterative design of peptide-based hydrogels and the effect of network electrostatics on primary chondrocyte behavior. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7478–7488. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veiga AS, Sinthuvanich C, Gaspar D, Franquelim HG, Castanho M, Schneider JP. Arginine-rich self-assembling peptides as potent antibacterial gels. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8907–8916. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan CQ, Mackay ME, Czymmek K, Nagarkar RP, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Injectable solid peptide hydrogel as a cell carrier: Effects of shear flow on hydrogels and cell payload. Langmuir. 2012;28:6076–6087. doi: 10.1021/la2041746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altunbas A, Lee SJ, Rajasekaran SA, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Encapsulation of curcumin in self-assembling peptide hydrogels as injectable drug delivery vehicles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5906–5914. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Branco MC, Pochan DJ, Wagner NJ, Schneider JP. The effect of protein structure on their controlled release from an injectable peptide hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9527–9534. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rughani RV, Branco MC, Pochan D, Schneider JP. De novo design of a shear-thin recoverable peptide-based hydrogel capable of intrafibrillar photopolymerization. Macromolecules. 2010;43:7924–7930. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan CQ, Altunbas A, Yucel T, Nagarkar RP, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Injectable solid hydrogel: Mechanism of shear-thinning and immediate recovery of injectable beta-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Soft Matter. 2010;6:5143–5156. doi: 10.1039/C0SM00642D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Branco MC, Pochan DJ, Wagner NJ, Schneider JP. Macromolecular diffusion and release from self-assembled beta-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haines-Butterick LA, Salick DA, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. In vitro assessment of the pro-inflammatory potential of beta-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4164–4169. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajagopal K, Lamm MS, Haines-Butterick LA, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Tuning the ph responsiveness of beta-hairpin peptide folding, self-assembly, and hydrogel material formation. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2619–2625. doi: 10.1021/bm900544e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salick DA, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Design of an injectable beta-hairpin peptide hydrogel that kills methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Adv Mater. 2009;21:4120. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haines-Butterick L, Rajagopal K, Branco M, Salick D, Rughani R, Pilarz M, et al. Controlling hydrogelation kinetics by peptide design for three-dimensional encapsulation and injectable delivery of cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7791–7796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701980104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hule RA, Nagarkar RP, Altunbas A, Ramay HR, Branco MC, Schneider JP, et al. Correlations between structure, material properties and bioproperties in self-assembled beta-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Faraday Discuss. 2008;139:251–264. doi: 10.1039/b717616c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salick DA, Kretsinger JK, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Inherent antibacterial activity of a peptide-based beta-hairpin hydrogel. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14793–14799. doi: 10.1021/ja076300z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagarkar RP, Schneider JP. Synthesis and primary characterization of selfassembled peptide-based hydrogels. Methods Mol Biol Clifton, NJ. 2008;474:61–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-480-3_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kyle S, Aggeli A, Ingham E, McPherson MJ. Recombinant self-assembling peptides as biomaterials for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9395–9405. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riley JM, Aggeli A, Koopmans RJ, McPherson MJ. Bioproduction and characterization of a ph responsive self-assembling peptide. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:241–251. doi: 10.1002/bit.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high-density shaking cultures. Protein Expres Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grathwohl C, Wuthrich K. X-pro peptide-bond as an nmr probe for conformational studies of flexible linear peptides. Biopolymers. 1976;15:2025–2041. doi: 10.1002/bip.1976.360151012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nair CM, Vijayan M, Venkatachalapathi YV, Balaram P. X-ray crystal-structure of pivaloyl-d-pro-l-pro-l-ala-N-methylamide - observation of a consecutive beta-turn conformation. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1979:1183–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. A revised set of potentials for beta-turn formation in proteins. Protein Sci. 1994;3:2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sibanda BL, Blundell TL, Thornton JM. Conformation of beta-hairpins in protein structures - a systematic classification with applications to modeling by homology, electron-density fitting and protein engineering. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:759–777. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson JS, Getzoff ED, Richardson DC. Beta-bulge - common small unit of nonrepetitive protein-structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2574–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blandl T, Cochran AG, Skelton NJ. Turn stability in beta-hairpin peptides: Investigation of peptides containing 3 : 5 type i g1 bulge turns. Protein Sci. 2003;12:237–247. doi: 10.1110/ps.0228603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Alba E, Rico M, Jimenez MA. The turn sequence directs beta-strand alignment in designed beta-hairpins. Protein Sci. 1999;8:2234–2244. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.11.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Searle MS, Williams DH, Packman LC. A short linear peptide derived from the n-terminal sequence of ubiquitin folds into a water-stable nonnative beta-hairpin. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:999–1006. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stanger HE, Gellman SH. Rules for antiparallel beta-sheet design: D-pro-gly is superior to l-asn-gly for beta-hairpin nucleation. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4236–4237. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Griffiths-Jones SR, Maynard AJ, Sharman GJ, Searle MS. Nmr evidence for the nucleation of a beta-hairpin peptide conformation in water by an asn-gly type i′ beta-turn sequence. Chem Commun. 1998:789–790. [Google Scholar]

- 62.RamirezAlvarado M, Blanco FJ, Niemann H, Serrano L. Role of beta-turn residues in beta-hairpin formation and stability in designed peptides. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:898–912. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murby M, Uhlen M, Stahl S. Upstream strategies to minimize proteolytic degradation upon recombinant production in escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1996;7:129–136. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gronenborn AM, Filpula DR, Essig NZ, Achari A, Whitlow M, Wingfield PT, et al. A novel, highly stable fold of the immunoglobulin binding domain of streptococcal protein-G. Science. 1991;253:657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1871600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuliopulos A, Walsh CT. Production, purification, and cleavage of tandem repeats of recombinant peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4599–4607. [Google Scholar]

- 66.LaVallie ER, DiBlasio-Smith EA, Collins-Racie LA, Lu Z, McCoy JM. Thioredoxin and related proteins as multifunctional fusion tags for soluble expression in E. coli Methods Mol Biol. 2003;205:119–140. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-301-1:119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Terpe K. Overview of tag protein fusions: From molecular and biochemical fundamentals to commercial systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;60:523–533. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. The p1′ specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:949–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bird GH, Bernal F, Pitter K, Walensky LD. Synthesis and biophysical characterization of stabilized alpha-helices of bcl-2 domains. Programmed Cell Death, the Biology and Therapeutic Implications of Cell Death, Part B. 2008:369–386. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of chemically synthesized EX1

Figure S2: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of chemically synthesized EX2

Figure S3: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of chemically synthesized EX3

Figure S4: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of recombinant EX1

Figure S5: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of recombinant EX2

Figure S6: Analytical HPLC (A) and corresponding pure ESI-MS (B) of recombinant EX3

Figure S7: Dynamic time sweep experiment of 1wt% chemically synthesized EX peptides.

Figure S8: Gel electrophoresis of purified fusion proteins with enzymatic cleavage site

Figure S9: Comparison of secondary structure and elastic properties of 1wt% EX2 and EX3 gels formed by chemically synthesized (cEX) and recombinant (rEX) peptides. Wavelength CD spectra of EX2 (A) and EX3 (B) peptide gels. Dynamic time sweep experiments of EX2 (C) and EX3 (D) peptide gels. Shear-thin and recovery experiment of EX2 (E) and EX3 (F) peptide gels.

Figure S10: Dynamic (A) frequency and (B) strain sweep experiments of 1wt% rEX gels at 37°C (pH 7.4, 50 mM BTP, 150 mM NaCl).

Figure S11: TEM analysis of local fibril morphologies of rEX2 and rEX3 peptide gels. Insets show the individual fibril widths. Scale bar is 100 nm.

Table S1: DNA Sequences of designed genes