Abstract

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) produced by vascular endothelial cells plays essential roles in the regulation of vascular tone and development of cardiovascular diseases. The objective of this study is to identify novel regulators implicated in the regulation of ET-1 expression in vascular endothelial cells (ECs). By using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), we show that either ectopic expression of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 or pharmacological activation of Nur77 by 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) substantially inhibits ET-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), under both basal and thrombin-stimulated conditions. Furthermore, thrombin-stimulated ET expression is significantly augmented in both Nur77 knockdown ECs and aort from Nur77 knockout mice, suggesting that Nur77 is a negative regulator of ET-1 expression. Inhibition of ET-1 expression by Nur77 occurs at gene transcriptional levels, since Nur77 potently inhibits ET-1 promoter activity, without affecting ET-1 mRNA stability. As shown in electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), Nur77 overexpression markedly inhibits both basal and thrombin-stimulated transcriptional activity of AP-1. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that Nur77 specially interacts with c-Jun and inhibits AP-1 dependent c-Jun promoter activity, which leads to a decreased expression of c-Jun, a critical component involved in both AP-1 transcriptional activity and ET-1 expression in ECs. These findings demonstrate that Nur77 is a novel negative regulator of ET-1 expression in vascular ECs through an inhibitory interaction with the c-Jun/AP-1 pathway. Activation of Nur77 may represent a useful therapeutic strategy for preventing certain cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis and pulmonary artery hypertension.

Keywords: Nur77, Endothelin-1, Transcription, AP-1, c-Jun

1. INTRODUCTION

ET-1, a 21-amino acid peptide, is released continuously and predominantly from vascular ECs and is of significant importance in the regulation of cardiovascular function [1]. Through binding to 2 types of receptors, namely ETA and ETB, ET-1 exerts multiple biological functions in the cardiovascular system, including vasoconstriction, proinflammatory and mitogenic properties in vascular ECs and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [2]. ETA receptors are mainly expressed in vascular SMC and cardiac myocytes, whereas ETB receptors are predominantly localized on ECs and certain vascular SMCs [3]. The binding of ET-1 to ETA and ETB receptors in vascular SMCs results in a potent vasoconstriction, whereas the activation of endothelial ETB receptors by ET-1 stimulates the release of NO and prostacyclin and causes an endothelium-dependent vasodilation [4, 5]. Recently, multiple lines of evidence suggest that increased expression of ET-1 has been implicated in the development of endothelial dysfunction, which is associated with many cardiovascular events, such as atherosclerosis and vascular complications in diabetes [6, 7]. In fact, the increased expression of ET-1 has been documented in atherosclerotic lesions and human coronary artery diseases [8] [9]. Furthermore, endothelial specific overexpression of ET-1 markedly increased the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in Apo-E knockout mice fed with a high fat diet [10], further implicating its essential role in the development of vascular diseases. In the lungs, increased ET-1 has been shown to cause potent vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling, hence, contributing significantly to the development of both primary and secondary pulmonary hypertension [11]. Accordingly, the ET-1 receptor antagonists have been shown to dramatically improve the clinical outcome of the patients with severe pulmonary artery hypertension [12].

Because of critical roles of ET-1 in cardiovascular system, its expression is tightly controlled and primarily regulated at the gene transcriptional levels [13]. Several transcriptional factors, including AP-1, GATA-2, vascular endothelial zinc finger 1(Vezf1), forkhead box O (FOXO), and NF-κB, have been identified to bind to the ET-1 promoter region and transcriptionally regulate the ET-1 expression [14–17]. The AP-1 binding site is located at −108 bp of human ET-1 promoter and recruits both c-Fos and c-Jun, which is of importance for the high basal levels of ET-1 promoter activity in ECs [14]. In addition, PKC dependent activation of AP-1 has also been shown to mediate the increased ET-1 expression stimulated by thrombin, angiotensin II, and High-density lipoprotein [18–20]. Recently, the nuclear receptors have emerged as critical regulators for the ET-1 expression in the cardiovascular system. For instance, through directly binding to the promoter of ET-1, both the mineralocorticoid receptor and the glucocorticoid receptors have been shown to mediate the aldosterone dependent induction of ET-1 expression [13]. Importantly, activation of several nuclear receptors, including estrogen receptor (ER), retinoic acid receptor (RAR), farnesoid X receptor (FXR), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) α and γ, has been shown to attenuate the ET-1 expression in vascular cells [19, 21–23], further implicating the functional importance of the nuclear receptor superfamily in the regulation of cardiovascular function.

NR4A receptors are immediate-early genes that are regulated by various physiological stimuli including growth factors, hormones, and inflammatory signals and involved in a wide array of important biological processes, including cell apoptosis, brain development, glucose and lipid metabolism, and vascular remodeling [24]. The NR4A subfamily consists of 3 well-conserved members, Nur77 (NR4A1), Nurr1 (NR4A2), and NOR-1 (NR4A3), respectively. Like other nuclear receptors, NR4A receptors consist of an N-terminal transactivation domain, a central 2-zinc-finger DNA-binding domain, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain. So far, no ligands have been identified for these receptors and therefore they are classified as orphan receptors. Recently, there has been much attention paid to the function of these receptors in cardiovascular system [25]. In vascular smooth muscle cells, the expression of Nur77 and NOR-1 was significantly induced by atherogenic stimuli, such as platelet-derived growth factor-BB, epidermal growth factor, and α-thrombin, and overexpression of Nur77 has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and attenuate vascular injury-induced neointimal formation in vivo [26] [27]. NR4A nuclear receptors are also induced in vascular ECs by several stimuli, such as hypoxia, TNF-α, and vascular endothelial growth factor, and modulate EC growth, survival, and angiogenesis [28] [29]. Most importantly, our recent study has implicated Nur77 as a potent negative regulator for the pro-inflammatory responses in ECs via a selective inhibition of NF-κB pathway [29]. Recently, Nur77 has been shown to inhibit the development of the atherosclerosis through its anti-inflammatory responses in microphages [30] [31]. Whether Nur77 elicits vascular protective effects through regulating ET-1 production, however, is undetermined.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of Nur77 on the expression of ET-1 in HUVECs. Our results demonstrated that Nur77 potently inhibited the ET-1 production under both basal and thrombin stimulated conditions. Mechanistically, we found that Nur77 inhibits ET-1 production at the gene transcriptional levels, through attenuating the expression of c-Jun, which is a critical component for the activation of AP-1 transcriptional pathway.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Cell Culture

Human umbilical vascular ECs (HUVECs) were purchased from ATCC and cultured in EBM-2 medium (Lonza) supplemented with EGM-2 BulletKit (Lonza). Human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in SmGM-2™ Growth Medium (Lonza). EA.hy926 cells and HEK293 cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

2.2. Mice

Nur77 knockout mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and animals were maintained on a C57BL/6 and 129SvJ hybrid background. Nur77+/− mice were crossed to obtain the wildtype and knockouts. Wildtype (WT) and Nur77 knockouts (KO) (10–12 weeks of age, 5–6 per group) were subjected to intraperitoneal injection (i.p) of thrombin (70 units/g body weight). 3 hours after injection, aorta from WT and Nur77 KO were then collected and total RNA was isolated by using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO/BRL) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The expression of ET-1 was then quantitated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Thomas Jefferson University.

2.3. Adenovirus Construction

Adenoviruses harboring wild-type Flag-tagged Nur77 (Ad-Nur77) and Nor1 (Ad-NOR1) were made using AdMax (Microbix) as previously described [29]. The viruses were propagated in Ad-293 cells and purified using CsCl2 banding followed by dialysis against 20 mmol/l Tris-buffered saline with 10% glycerol.

2.4. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Lac Z, Ad-Nur77 for 48 h and then treated with or without 10 U/ml thrombin (Haematologic Technologies) for 4 hours, subcellular fractions were prepared as described previously [29]. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) were performed with Odyssey® IRDye® 700 infrared dye labelled double-stranded oligonucleotides coupled with the EMSA buffer kit (LI-COR Bioscience) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The specificity of the binding was examined using competition experiments, where 100-fold excess of the unlabelled oligonucleotides were added to the reaction mixture prior to add the infrared dye labelled oligonucleotide. The gel supershift assay was performed by adding c-Jun antibody (Cell Signaling) for AP-1 prior to the addition of the fluorescently labeled probe.

2.5. Western blot

Cell lysates were made using RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) containing 25mM Tris•HCl pH 7.6, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and proteinase inhibitor cocktail containing 2 mM PMSF, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 10μg/ml leupeptin. Supernatants were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose (BioRad). Blots were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and then developed with diluted antibodies for Flag (1:1000 dilution; Genescript), Nur77 (1:250 dilution; BD Biosciences), GAPDH (1:2000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and c-Jun (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling) at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (DyLight 680 conjugated, Thermo Scientific) or goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (DyLight 800 conjugated, Thermo Scientific) for 1 hour.

2.6. Co-immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously [29]. After preclearing for 1 hour at 4°C with protein A/G agarose (Sigma Aldrich). Anti-flag M2 agarose (Sigma Aldrich) was added, and immune complexes were collected after overnight incubation at 4°C. To identify the binding domains of Nur77 and c-Jun, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with flagged tagged Nur77 mutant and Myc-tagged c-Jun mutant cDNAs using FuGENE 6 as described by the manufacturer (Roche Applied Science). Coimmunoprecipitation of Nur77 and c-Jun in HEK293 cells was performed essentially as described [29]. The following antibodies were used for detection and immunoprecipitation: rabbit polyclonal c-Myc (Invitrogen), mouse monoclonal FLAG M2 (Sigma), and rabbit polyclonal c-Jun (Cell Signaling). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)(DyLight 680 conjugated, Thermo Scientific) or goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (DyLight 800 conjugated, Thermo Scientific). Blots were visualized on an Odyssey Imaging System (Licor). The intensity of the bands was quantified by using the Odyssey software.

2.7. Knockdown of Nur77 and c-Jun by Small Interfering RNA

Human Nur77 (5′-GGCUUGAGCUGCAGAAUGA-3′, and 5′-UCAUUCUGCAGCUCAAGCC-3′), human c-Jun (Santa Cruz), and a negative control siRNA (Sigma–Aldrich) were used for the transfection of HUVECs with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen) in serum-free medium according to the recommendations of the manufacturer.

2.8. Quantitative Real Time-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells and treated with DNase I using the RNeasy® Micro kit (Qiagen). mRNA levels of human Nur77 and ET-1 were determined by qRT-PCR using cDNA obtained from the reverse transcription reactions as template, with MyiQ™ Single-Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and HotStart-IT SYBR Green One-Step qRT-PCR Master Mix Kit (Affymetrix). The primer sequences are described as follows: human Nur77 forward, 5′-AAGATCCCTGGCTTTGCTGAGCTG-3′ and reverse 5′-AGGCCAGGATACTGTCAATCCAGT-3′; human ET-1 forward, 5′-GCTCGTCCCTGATGGATAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-ATTCTCACGGTCTGTTGCCT-3′; Mouse ET-1 forward, 5′-TCCTCTGCCCGTCTGAACAAGAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCATCAGCAATAGCATCAAGGCA-3′; 18S forward, 5′-TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCAC-3′; 18S mRNA served as a control for the amount of cDNA present in each sample. Data were analyzed using the comparative difference in cycle number (ΔCT) method according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.9. Measurement of Endothelin-1 by ELISA

HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Lac Z, Ad-Nur77 for 48 hours as described above. Supernatants were collected before and after stimulation of thrombin at 4 U/ml for 24 hours. Human Endothelin-1 QuantiGlo ELISA Kit (R&D systems) was used for the quantitative determination of human ET-1.

2.10. Transient Transfection and luciferase assay

The human ET-1 promoter was amplified by PCR using human genomic DNA (Clontech) with primers and cloned into the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3-Basic (Promega). A luciferase reporter regulated by 7 tandem AP-1 repeats was purchased from Stratagene. NBRE-luc reporter plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Astar Winoto (University of California, Berkeley). HUVECs were seeded in 24-well plates and incubated overnight. The cells were transfected with either 200 ng pGL3-ET-1 promoter luciferase reporter, c-Jun promoter luciferase reporter or NBRE luciferase reporter in the presence or absence of indicated expression vectors using Lipofectamine™ LTX (Invitrogen) transfection reagent. 36 hrs after transfection, cells were treated with or without 4U/ml thrombin for 6 hr or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP, Sigma–Aldrich) for 24 hr, then directly lysed in the lysis buffer (Promega). 20 μl of the cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity with a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and determined with a Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.11. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate) according to the instructions of the manufacture. Soluble chromatin was prepared from HUVECs transduced with either Ad-LacZ or Ad-Nur77 (MOI=100) for 48 hours. DNA-bound c-Jun subunit was immunoprecipitated by incubating with antibody directed against c-Jun (5 μg, Cell Signaling) overnight at 4°C with rotation. After reversal of cross links and digestion of bound proteins, the recovered DNA was quantified by PCR amplified using primer pairs that cover an AP-1 consensus sequence in the ET-1 promoter as follows: sense, 5′-GCCTCTGAAGTTAGCAGTGA-3′; antisense: 5′-GGGGTAAACAGCTCCGACTT-3′.

2.12. Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. The statistical significance of differences was assessed with unpaired Student’s t test or ANOVA, as appropriate; In all cases, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Overexpression of Nur77 inhibits ET-1 expression in HUVECs

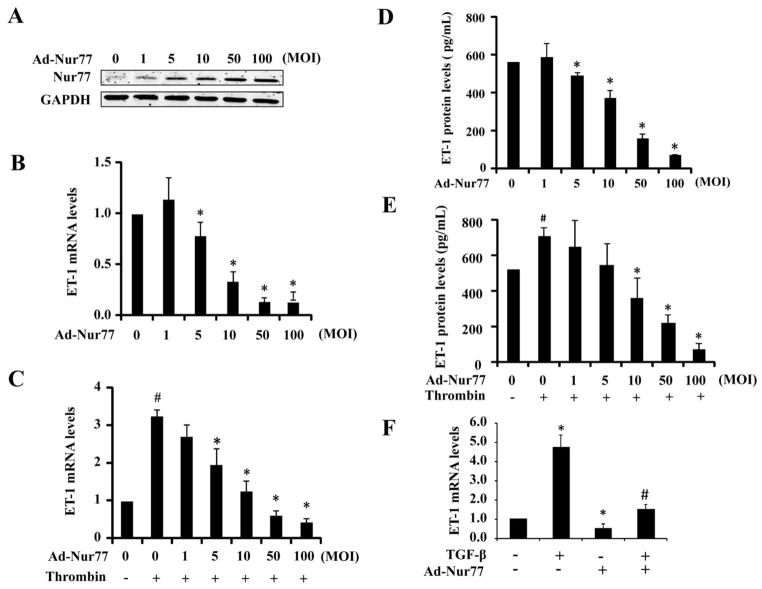

To investigate the role of Nur77 in the regulation of ET-1 expression in ECs, we transduced the HUVECs with recombinant adenovirus bearing human Nur77 cDNA (Ad-Nur77). Transduction of HUVECs with increasing MOIs of Ad-Nur77 led to an increased expression of Nur77 (Figure 1A). To determine whether Nur77 affects the ET-1 expression in ECs, we examined the effect of adenovirus mediated Nur77 over-expression on ET-1 mRNA levels, under both basal and thrombin-stimulated conditions, by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 1B, under basal unstimulated conditions, Nur77 overexpression markedly inhibited the ET-1 expression in a dose dependent manner. Likewise, the thrombin-induced ET-1 expression was also substantially inhibited (Figure 1C). To detect whether Nur77 influences the ET-1 peptide levels in cultured HUVECs, we performed ELISA to determine the levels of ET-1 in the supernatants of HUVECs. Consistent with the ET-1 gene expression results, in a dose dependent manner, Nur77 overexpression markedly inhibited the ET-1 levels under both basal and thrombin stimulated conditions (Figure 1D and 1E). Furthermore, Nur77 overexpression also significantly attenuated the basal and TGF-β1-stimullated ET-1 expression in human pulmonary artery sooth muscle cells (Figure 1F). The expression of both ETA and ETB receptors in HUVECs was not altered by Nur77 overexpression. Taken together, these results suggest that Nur77 may be a critical regulator for the ET-1 expression in vascular cells.

Figure 1. Nur77 inhibits both basal and thrombin-induced ET-1 expression.

(A) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 at indicated mois. 48 hours after transduction, total protein was extracted for the detection of Nur77 expression by western blot analysis. (B) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 at the indicated mois. 48 hours after transduction, ET-1 mRNA expression was detected by qRT- PCR. *P<0.05 compared with MOI=0; n=3. (C) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 at the indicated mois. 48 hours after transduction, HUVECs were treated with 4 U/ml thrombin for 2 hours. ET-1 mRNA expression was detected by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 compared with MOI=0 without thrombin stimulation; #P<0.05 compared with MOI=0 with thrombin stimulation. n=3. (D) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 at indicated mois. 48 hours after transduction, ET-1 expression was measured by ELISA in HUVEC supernatants. *P<0.05 compared with MOI=0. n=3. (E) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 at indicated mois. 48 hours after transduction, HUVECs were treated with 4 U/ml thrombin for 24 hours. The ET-1 levels in supernatants were measured by ELISA. *P<0.05 compared with MOI=0 without thrombin stimulation; # P<0.05 compared with MOI=0 with thrombin stimulation. n=3. (F) HPASMCs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 (mois 100). 24 hours after transduction, cells were starved for 48 hours and stimulated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours, the expression of ET-1 was determined by detected by qRT- PCR. *P<0.05 compared with no TGF-β1/Ad-Nur77 treatment; #P<0.05 compared with TGF-β1 without Ad-Nur77 treatment; n=3.

3.2 Knockdown of Nur77 augments ET-1 expression in ECs

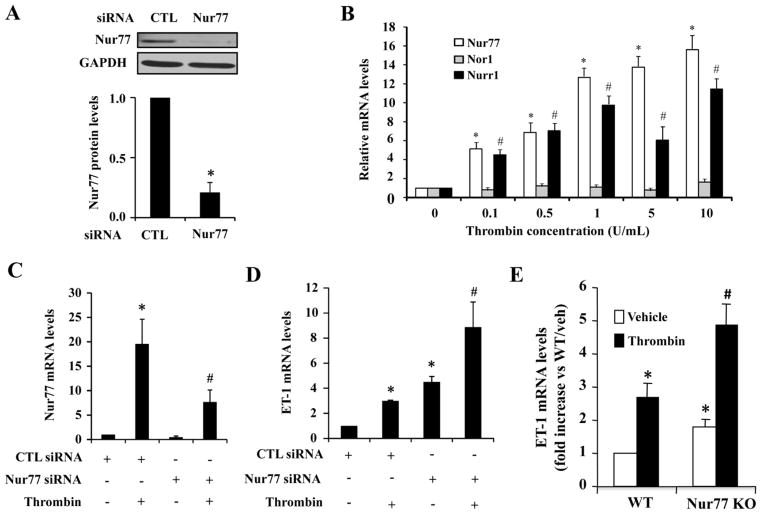

After demonstrating the inhibitory effect of Nur77 on ET-1 expression in HUVECs, we attempted to define the role of endogenous Nur77 in the regulation of ET-1 in ECs by performing loss-of-function studies using Nur77 specific siRNA. Transfection of HUVECs with Nur77 specific siRNA markedly inhibited the expression of Nur77 in HUVECs by approximately 70% (Figure 2A), but not affect the expression of other NR4A members, including Nor1 and Nurr1 (data not shown). Interestingly, consistent with the previous report showing that thrombin increases the expression of Nur77 in VSMCs [24], thrombin (4 U/ml) markedly increased Nur77 and NOR-1 expression in HUVECs (Figure 2B). In HUVECs transfected with Nur77 siRNA, both basal and thrombin-induced Nur77 expression were markedly attenuated (Figure 2C). Furthermore, we sought to examine the ET-1 expression, by using qRT-PCR, under both basal and thrombin stimulated conditions. As shown in Figure 2D, expression of ET-1 was markedly augmented in Nur77 knockdown ECs. To further substantiate the functional significance of Nur77 in regulating ET-1 expression in vivo, we investigated the effect of Nur77 deficiency on ET-1 expression by using Nur77 knockout mice. As shown in Figure 2E, both basal and thrombin-induced ET-1 expression was substantially increased in the aorta of Nur77 knockout mice, as compared to their wild-type littermate control. Together, these results suggest that Nur77 functions as an endogenous inhibitor for ET-1 expression in vasculature.

Figure 2. Nur77 knockdown augments both basal and thrombin-induced ET-1 expression in HUVECs.

(A) HUVECs were treated with thrombin at different concentrations for 2 hours. The expression of Nur77, Nurr1 and Nor1 were detected by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 compared with control; #P<0.05 compared with control. (B) 72 hours after transfection of Nur77-specific siRNA or control siRNA, the Nur77 protein was determined by western blotting analysis. (C) 72 hrs after transfection of Nur77-specific siRNA or control siRNA, HUVECs were treated with or without 4 U/ml thrombin for 2 hours. The expression of Nur77 was detected by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 compared with control; # indicates P<0.05 compared with control plus thrombin stimulation. (D) 72 hours after transfection of siRNA, HUVECs were treated with or without 4U/ml thrombin for 2 hours. The expression of ET-1 mRNA was detected by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 compared with control; # indicates P<0.05 compared with control plus thrombin stimulation. (E) Wildtype and Nur77 knockout mice were intraperitoneally injected with thrombin (70 units/g body weight). 3 hours after injection, total RNA was extracted from aorta and the expression of ET-1 was then quantitated by qRT-PCR. * indicates P<0.05 compared with WT mice injected with PBS; # indicates P<0.05 compared with WT mice injected with thrombin. qRT-PCR results are shown as means ± SEM and the data is representative of three individual experiments.

3.3. 6-MP inhibits ET-1 expression through activation of Nur77 in ECs

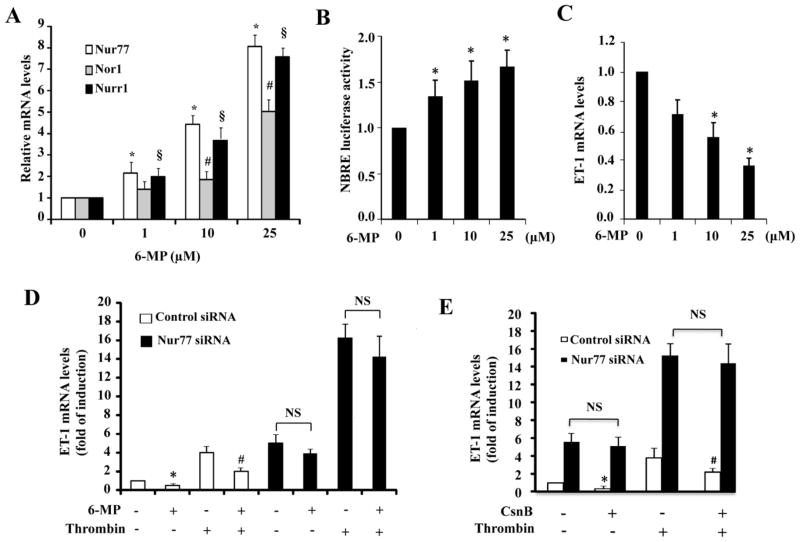

To examine whether pharmacological activation of Nur77 could affect the ET-1 expression in ECs, we employed 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), which was previously identified as an activator of Nur77 [32]. First, we examined whether 6-MP induces the expression of NR4A family in HUVECs. Consistent with the previous report [32], 6-MP, indeed, dose-dependently increased the expression of Nur77 in HUVECs, as determined by qRT-PCR. At the concentration of 25 μM, the expression of Nur77 was increased about 8-fold (Figure 3A). Accordingly, the transcriptional activity of Nur77, as determined by the Nur77-binding response element (NBRE) driven luciferase activity, was also significantly increased (Figure 3B). To investigate whether 6-MP affects the ET-1 expression in HUVECs, we then treated HUVECs with increasing concentrations of 6-MP. As shown in Figure 3C, 6-MP markedly inhibited the ET-1 gene expression in a dose dependent manner. Additionally, in control siRNA transfected cells, the thrombin-stimulated ET-1 production was also inhibited by approximately 60% by 6-MP (Figure 3D). However, in Nur77 knockdown cells, 6-MP-induced inhibitory effect on ET-1 expression was substantially diminished (Figure 3D), under both basal and thrombin stimulated conditions. Furthermore, cytosporone B, which has been shown to activate Nur77 [33], also markedly inhibited both basal and thrombin induced ET-1 expression in a Nur77 dependent manner. Together, these results highlight the functional importance of Nur77 in the regulation of ET-1 expression in ECs.

Figure 3. 6-MP inhibits ET-1 expression through induction of Nur77 in ECs.

(A) HUVECs were treated with 6-MP at different concentrations for 3 hours. The expression of NR4A receptors was detected by qRT-PCR. *, #, §P<0.05 compared with no 6-MP stimulation. (B) HUVECs were transfected with 200 ng of NBRE-luc and the luciferase assays were performed 24 hours after treatment with 6-MP. *P<0.05 compared with no 6-MP stimulation. (C) HUVECs were treated with 6-MP for 3 hours. ET-1 mRNA was detected by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 compared with no 6-MP stimulation. (D) HUVECs were transfected with Nur77-specific siRNA and control siRNA. 72 hours after transfection, HUVECs were pretreated with 25 μM 6-MP for 2 hours and then treated with 4 U/ml thrombin for 2 hours. ET-1 mRNA levels were detected by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 compared with no 6-MP/thrombin; #P<0.05 compared with no 6-MP but with thrombin; NS indicates non-significant. qRT-PCR results and luciferase results are shown as means ± SEM. All the data is representative of 4 individual experiments. (E) HUVECs were transfected with either control siRNA or specific Nur77 siRNA. 72 hours after transfection, HUVECs were then treated with or without 10μM cytosporoneB (CsnB) for 1 hour and then treated with 10 U/ml thrombin for 2 hours. ET-1 mRNA levels were detected by qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR results are shown as means ± SEM and the data is representative of three individual experiments. * P<0.05 compared with control siRNA transfected cells treated with vehicle; # indicates P<0.05 compared with control siRNA transfected cells treated with thrombin.

3.4. Nur77 downregulates ET-1 Expression at transcriptional levels

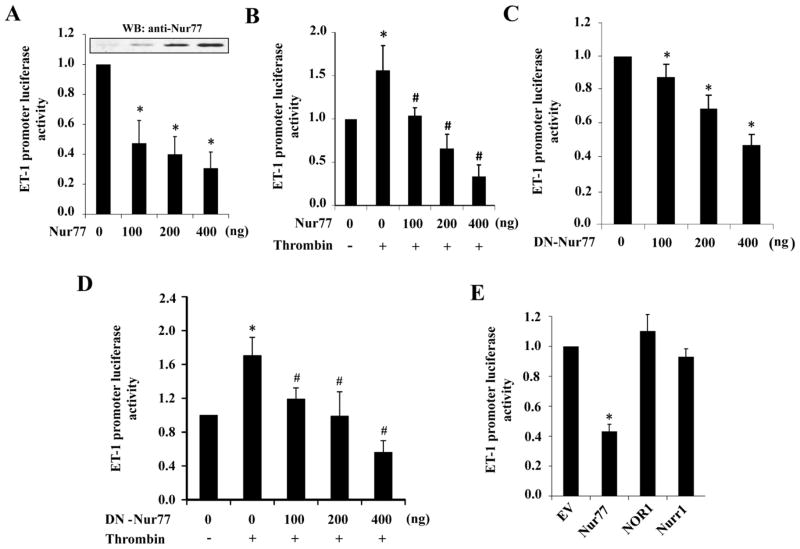

Since ET-1 expression is mainly regulated at gene transcriptional levels [13], to determine the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of ET-1 by Nur77, we investigated the effect of Nur77 on ET-1 promoter activity. As shown in Figure 4A and 4B, ectopic expression of Nur77 not only inhibited the basal ET-1 promoter activity, but also substantially inhibited the thrombin-induced ET-1 promoter activity. Interestingly, the dominant negative Nur77 (DN-Nur77), which lacks the transcriptional activation domain of Nur77 [29], also markedly inhibited both basal and thrombin-induced ET-1 promoter activity (Figure 4C and 4D), indicating that the non-genomic effect of Nur77 might be involved in the regulation of ET-1 in ECs. Furthermore, ET-1 promoter activity was only inhibited by Nur77, but not by NOR-1 and Nurr1 (Figure 4E), indicating the specificity of NR4A family receptors in the regulation of ET-1 expression. Taken together, these findings indicate that Nur77 transcriptionally regulates the expression of ET-1, probably through its non-genomic effect in ECs.

Figure 4. Nur77 inhibits ET-1 promoter activity.

(A) EA.hy926 cells were transfected with 200 ng of pGL3-ET-1 promoter-luc with increasing amounts of pFlag-Nur77. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed. *P<0.05 compared with no Nur77. (B) EA.hy926 cells were transfected with 200 ng of pGL3-ET-1 promoter-luc with increasing amounts of pFlag-Nur77. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed 6 hours after treatment with10 U/ml thrombin. *P<0.05 compared with thrombin without Nur77; #P<0.05 compared with thrombin stimulation without Nur77. (C) EA.hy926 cells were transfected with 200 ng of pGL3-ET-1 promoter-luc together with increasing amounts of pFlag-DN-Nur77. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed. *P<0.05 compared with no DN-Nur77. (D) EA.hy926 cells were transfected with 200 ng of pGL3-ET-1 promoter-luc with increasing amounts of pFlag-DN-Nur77. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed 6 hours after treatment with10 U/ml thrombin. *P<0.05 compared with thrombin stimulation without DN-Nur77; #P<0.05 compared with thrombin stimulation without DN-Nur77. (E) EA.hy926 cells were transfected with 200 ng of pGL3-ET-1 promoter-luc with either Nur77 or NOR-1 or Nurr1 expression vectors. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed. *P<0.05 compared with empty vector (EV). Luciferase results are shown as means ± SEM and the data is representative of four individual experiments.

3.5. Nur77 attenuates ET-1 transcription by inhibiting the AP-1 transcriptional activity

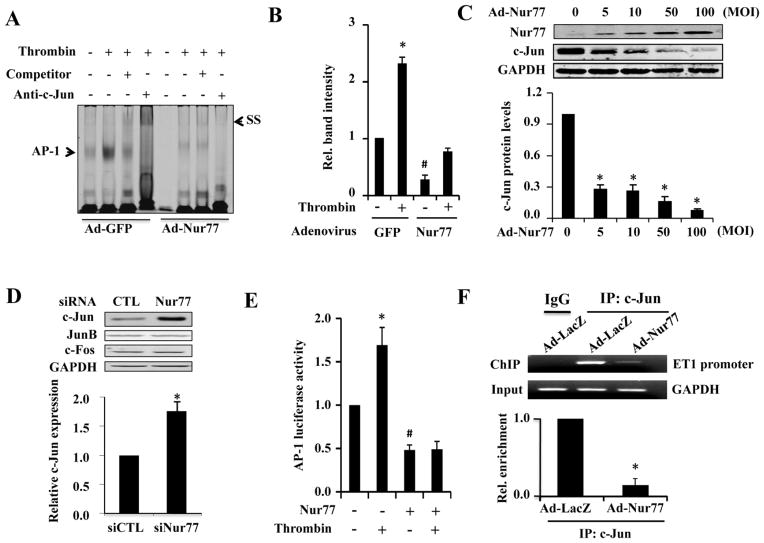

AP-1 site is essential for the activation of ET-1 promoter in endothelial cells [14]. To determine whether AP1 participates in the Nur77-mediated inhibition on ET-1 expression, we performed EMSA to determine whether Nur77 affects the AP-1 activity in the nuclear extracts of thrombin stimulated HUVECs. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, transduction of HUVECs with Ad-Nur77 significantly attenuated the basal AP-1 binding activity, as compared with that in Ad-GFP transduced cells. Furthermore, in Ad-GFP transduced HUVECs, thrombin markedly increased the AP1 binding activity, which was substantially inhibited when Nur77 was overexpressed, suggesting that Nur77 inhibits the ET-1 expression through attenuating the AP1 transcriptional activity. Strikingly, in a dose dependent manner, Nur77 overexpression was found to inhibit the expression of c-Jun (Figure 5C), which is a major component of the AP1 transcriptional complex. Moreover, knockdown of Nur77 specifically increased the expression of c-Jun, but barely affected the expression of Jun B and c-fos (Figure 5D), further implicating the role of Nur77 in regulating c-Jun expression. Consistent with the results obtained in EMSA, Nur77 overexpression markedly inhibited the AP-1 dependent luciferase activity, under both basal and thrombin stimulated conditions (Figure 5E). In addition, the binding of c-Jun to the AP-1 consensus site in ET-1 promoter was significantly attenuated by Nur77 (Figure 5F). Together, these results suggest that Nur77 attenuates the ET-1 expression and AP-1 transcriptional pathway by inhibiting c-Jun expression in HUVECs.

Figure 5. Nur77 inhibits thrombin induced AP-1 activation through inhibiting c-Jun expression.

(A) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-GFP, Ad-Nur77 (mois 100) for 48 hours and then treated in the presence or absence of 4 U/ml thrombin for 4 hours. Nuclear protein was extracted and EMSA was performed. (B) quantitative analysis of AP-1 binding intensity from three independent experiments. Band intensity was normalized to Ad-GFP without thrombin stimulation. *P<0.05 compared with Ad-GFP without thrombin stimulation or Ad-Nur77 plus thrombin; #P<0.05 compared with Ad-GFP without thrombin. (C) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Nur77 at the indicated mois. 48 hours after transduction, the total protein was extracted for the western blot analysis of Nur77 and c-Jun expression. Quantitative data from three independent experiments was shown. *P<0.05 compared with MOI=0. (D) 72 hours after transfection of Nur77-specific siRNA or control siRNA in HUVECs, the protein expression of c-Jun, JunB, and c-Fos was determined by western blotting analysis. (E) EA.hy926 cells were transfected with 200 ng AP-1 promoter-luc and 200 ng of either empty vector (EV) or pFlag-Nur77. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed with or without treatment of 4 U/ml thrombin for 6 hours (n=5). *P<0.05 compared with no Nur77 and no thrombin or Nur77 plus thrombin; #P<0.05 compared with thrombin without Nur77. (F) Nur77 inhibits the binding activity of c-Jun to ET-1 promoter. HUVECs were transduced with either Ad-GFP or Ad-Nur77 for 72 hours. PCR analysis of sheared DNA from control and adenovirus infected cells before immunoprecipitation (input) and after Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with antibody directed against c-Jun. Quantitative analysis of ChiP result from three independent experiments.

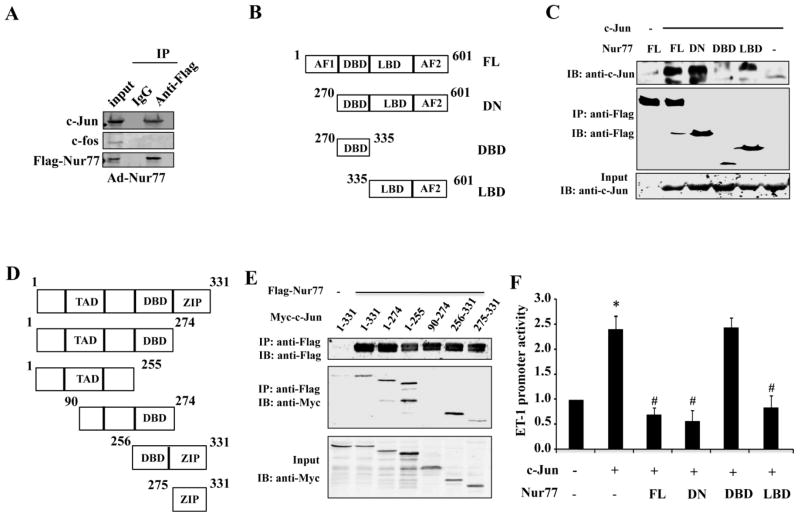

3.6. Nur77 attenuates AP-1 activity through inhibiting c-Jun transcription

Having shown that the c-Jun expression was down-regulated by Nur77 in ECs, we sought to determine the molecular mechanism involved. Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of c-Jun is primarily regulated at the transcriptional levels, and is mainly involved in the binding of AP-1 to the c-Jun gene promoter [34, 35]. In addition, the non-genomic effect of Nur77 on ET-1 promoter activity, as shown in Figure 4C and 4D, further indicates that a protein-protein interaction might contribute to the regulation of ET-1 by Nur77. Therefore, we attempted to speculate that Nur77 might inhibit the c-Jun gene expression through an inhibitory interaction with the transcriptional factor AP-1. To this end, we investigated the potential interaction of Nur77 with c-Jun in HUVECs by using immunoprecipitation. As shown in Figure 6A, immunopreciptation of the Flag-tagged Nur77 led to a co-immunoprecipitation of c-Jun with Nur77 in the nuclear fraction of ECs. Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation in HEK293 cells indicated that the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of Nur77 specifically interacted with c-Jun (Figure 6B and 6C), while both N-terminal and C-terminal fragments of c-Jun interact with Nur77 (Figure 6D and 7E). Accordingly, c-Jun-induced activation of ET-1 promoter was inhibited by the full-length Nur77, DN-Nur77, and Nur77 LBD, but not by DNA binding domain (DBD) of Nur77 (Figure 6F), further indicating the importance of Nur77-c-Jun interaction in regulating ET-1 expression.

Figure 6. Functional interaction of Nur77 with c-Jun.

(A) HUVECs were transduced with Ad-LacZ or Ad-Nur77 for 48 hours. Nuclear fraction was isolated and immunoprecipitation was performed with either normal IgG or anti-Flag M2 antibody. Immunocomplexes were washed and then separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The transferred membrane was immunoblotted with either anti-Flag, anti-c-Jun or anti-fos antibody. (B) Schematic representation of Flag Nur77 domains and deletion mutants. (C) c-Jun expression vector in combination with either empty vector or expression vectors of Flag-Nur77 mutants were co-transfected into HEK293 cells. Extracted proteins were precipitated by anti-Flag antibody and then separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The transferred membrane was immunoblotted with either anti-FLAG or anti-c-Jun antibody. (D) Schematic representation of myc-c-Jun domains. (E) Flag-Nur77 expression vector in combination with either empty vector or expression vectors of c-Jun mutant domains were co-transfected into HEK293 cells. Extracted proteins were precipitated by anti-Flag antibody. (F) EA.hy926 cells in 24 wells plate were co-transfected with 300ng of ET-1-Luc, 300ng Flag-Nur77, 300ng DN-Nur77, 300ng DBD-Nur77 and 300ng LBD-Nur77, as indicated, 50ng RL-SV40 as control. The total DNA content was equalized in each well. The relative promoter activities were calculated from the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activities. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assays were performed. Luciferase results are shown as means ± SEM and the data is representative of four individual experiments.

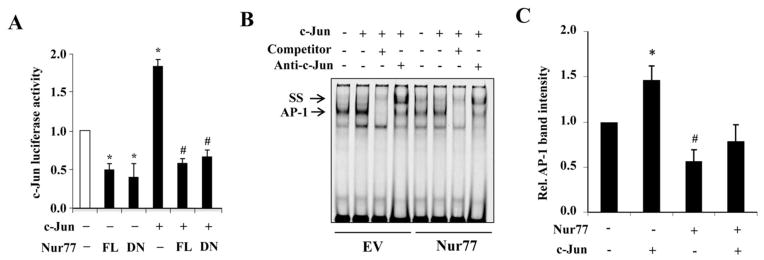

Figure 7. Nur77 inhibits c-Jun dependent transcriptional activity.

(A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with 200 ng c-Jun promoter-luc together with either 200 ng Nur77, DN-Nur77, c-Jun or empty vector as indicated. 36 hours after transfection, luciferase assay was performed. *P<0.05 compared with empty vectors. #P<0.05 compared with c-Jun vector. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with c-Jun and Nur77 expression plasmids as indicated for 36 hours and nuclear protein was extracted and EMSA was performed. (C) Quantitative analysis of AP-1 binding intensity from three independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with either empty vector or Nur77 plus c-Jun. #P<0.05 compared with empty vector.

To further determine the functional importance of this interaction in the regulation of c-Jun expression, we investigated whether Nur77 inhibits the AP-1 dependent c-Jun promoter activity. As shown in Figure 7A, c-Jun overexpression significantly increased the c-Jun promoter driven luciferase activity, which was markedly inhibited by overexpression of either wild-type Nur77 or DN-Nur77. Similarly, overexpression of c-Jun resulted in an increased AP1 binding activity to its consensus site, as determined by EMSA, which was also substantially inhibited by Nur77 overexpression (Figure 7B and 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that Nur77 inhibits the c-Jun expression through functionally interacting with c-Jun and subsequently inhibiting the AP-1 binding to the c-Jun promoter.

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we for the first time demonstrated that Nur77 is a novel negative regulator of ET-1 expression in vascular ECs. Ectopic expression of Nur77 suppresses the expression of ET-1 at transcriptional levels through inhibiting the AP1 transcriptional activity, which is a key transcriptional factor implicated in both basal and thrombin-induced ET-1 expression in vascular ECs. Furthermore, we show that 6-MP, a pharmacological activator of Nur77, potently inhibits ET-1 expression in ECs through an induction of Nur77, which is in fact consistent with a recent study showing that 6-MP decreases ET-1 production in an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) model [36]. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that Nur77 functionally interacts with c-Jun, which leads to an inhibition of AP1 transcriptional activity and attenuation of c-Jun expression in vascular ECs.

Transcriptional regulation is thought to be a major mechanism controlling ET-1 bioavailability [13]. Several key transcriptional factors, including Vezf1, FOXO1, GATA-2, AP-1, and NF-κB, have been shown to be involved in this process [14–17]. Our data also indicate that Nur77 inhibits the transcriptional activity of AP-1, a critical transcriptional factor implicated in both basal and induced transcription of ET-1 by thrombin. In vascular ECs, AP-1 is composed of two important major components, namely, c-Fos and c-Jun. c-Jun is the founding member and the most potent transcriptional activator of the AP-1 family [37]. Indeed, thrombin has been shown to increase c-Jun mRNA levels and AP-1 binding activity, which contributes significantly to the increased expression of ET-1 in vascular ECs [38]. Consistent with this role, the activation of nuclear receptors, such as PPARγ, ER, and FXR, has been shown to inhibit the ET-1 expression in vascular ECs by forming a nonproductive complex with c-Jun, and thus preventing the AP-1 binding to the ET-1 promoter [19, 21–23]. Phosphorylation of c-Jun has been implicated in the initiation of the AP1 activation, however, AP-1 activity is more closely associated with a steady elevation of c-Jun expression [39]. Indeed, a high-affinity AP-1 binding site has been identified in the c-Jun promoter, thus constituting a positive feedback circuit in the regulation of AP1 activity, in which AP-1 can activate the c-Jun promoter and gene expression to further enhance AP-1 activity and potentiate its gene promoter activation [39]. In the present study, we demonstrate that Nur77 potently inhibits the ET-1 promoter activity through suppressing the expression of c-Jun in vascular ECs. Furthermore, we showed that in the nucleus of endothelial cells, Nur77 is specifically associated with c-Jun, which in turn inhibits the AP-1 transcriptional activity and AP-1 dependent c-Jun promoter activity. In this regard, our findings provide significant novel insights into the molecular mechanism controlling the activation of AP-1 and ET-1 expression in ECs under both physiological and patho-physiological conditions.

NR4A receptors are immediate-early genes that are regulated by various physiological stimuli including growth factors, hormones, and inflammatory signals in cardiovascular system [25]. An increasing number of evidence suggests that NR4A receptors are highly expressed in advanced atherosclerotic lesions and injury induced vasculature [27]. Additionally, Nur77 deficiency has recently been shown to promote the development of atherosclerotic lesions in Apo-E knockout mice fed with a high fat diet through modulating inflammatory responses in microphages [31], further implicating their important roles in vascular diseases. Since ET-1 is highly expression in human atherosclerotic lesions [8, 9], it is attempted to speculate that Nur77 deficiency may cause a higher expression of ET-1 and this may partially contribute to the increased atherosclerotic formation in Nur77 knockout mice. Depending on the stimuli and its cellular localization, Nur77 can exert biological effects through both genomic and non-genomic actions [40]. For instance, in response to certain apoptosis-inducing agents, Nur77 expression is induced in some cancer cells, and subsequently translocates from the nucleus to mitochondria, where it causes the conformational change of Bcl-2 to promote apoptosis [41]. While in the nucleus, Nur77 can function as a transcription factor by binding to its DNA response elements to regulate the expression of its target genes [29]. In this study, our data suggest that such a genomic action of Nur77 is not likely involved in its inhibitory effect on ET-1 expression in vascular ECs, since DN-Nur77, which lacks the functional N-terminal AF-1 domain of Nur77, exerts the same inhibition on ET-1 promoter activity as wild-type Nur77. In addition, the sequential analysis of the c-Jun promoter did not reveal any potential Nur77 binding sites, further suggesting that the nongenomic action of Nur77, such as protein-protein interactions, may contribute to its inhibitory effect on ET-1 expression. Indeed, our results demonstrate that Nur77 functionally interacts with c-Jun in ECs and inhibits the AP-1-mediated c-Jun and ET-1 expression.

Recently, the NF-κB pathway has been shown to be involved in the regulation of ET-1 expression by some inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α [42]. In endothelial cells, our recent study demonstrated that Nur77 transcriptionally up-regulates the expression of IKBα via directly binding to the promoter region of IKBα, which eventually leads to the suppression of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway in ECs under inflammatory conditions[29]. Indeed, in this study, we found that in addition to inhibiting thrombin-stimulated ET-1 expression, Nur77 also markedly inhibited IL-1β-induced ET-1 expression in HUVECs through inhibiting NF-κB activation (data not shown). Furthermore, we found that hypoxia induced ET-1 expression was also markedly inhibited, although Nur77 increases HIF1α expression in ECs (data not shown). In this regard, our finding is consistent with the notion showing that a cooperative interaction between AP-1 and HIF1α is necessary for the hypoxia induced ET-1 expression[43]. Therefore, it is attempting to speculate that Nur77 may inhibit ET-1 expression in response to multiple stimuli, through both genomic and non-genomic actions, thus eliciting its vascular protective effects under various patho-physiological circumstances.

In summary, the data reported herein provide the evidence that the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 is a novel negative regulator of ET- expression in vascular ECs. Specifically, Nur77 interacts with c-Jun and functionally inhibits the AP-1 dependent ET-1 promoter activity through suppressing the expression of c-Jun. Given the critical roles of both ET-1 and AP-1 in the regulation of cardiovascular function, identification of Nur77 as a negative regulator of ET-1 production in vascular ECs may provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of atherosclerosis, vascular complications of diabetes, and pulmonary artery hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The role of Nur77 in regulating endothelin-1 expression was examined.

Nur77 inhibits endothelin-1 expression in vascular endothelial cells.

Nur77 inhibits endothelin-1 promoter activity through attenuating AP-1 activity.

Nur77 interacts with and suppresses c-Jun expression.

Acknowledgments

Founding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01HL103869 to J. S and the Chinese Natural Science Foundation No. 81000044 to Q. Q

Abbreviations

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- EMSA

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- siRNA

small interference RNA

- NBRE

Nur77-binding response element

- 6-MP

6 mercaptopurine

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abraham D, Dashwood M. Endothelin--role in vascular disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47 (Suppl 5):v23–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iglarz M, Clozel M. Mechanisms of ET-1-induced endothelial dysfunction. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology. 2007;50:621–8. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31813c6cc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seo B, Oemar BS, Siebenmann R, von Segesser L, Luscher TF. Both ETA and ETB receptors mediate contraction to endothelin-1 in human blood vessels. Circulation. 1994;89:1203–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luscher TF, Barton M. Endothelins and endothelin receptor antagonists: therapeutic considerations for a novel class of cardiovascular drugs. Circulation. 2000;102:2434–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzuca MQ, Khalil RA. Vascular endothelin receptor type B: structure, function and dysregulation in vascular disease. Biochemical pharmacology. 2012;84:147–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton M. Endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis: endothelin receptor antagonists as novel therapeutics. Current hypertension reports. 2000;2:84–91. doi: 10.1007/s11906-000-0064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vignon-Zellweger N, Heiden S, Miyauchi T, Emoto N. Endothelin and endothelin receptors in the renal and cardiovascular systems. Life sciences. 2012;91:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lerman A, Edwards BS, Hallett JW, Heublein DM, Sandberg SM, Burnett JC., Jr Circulating and tissue endothelin immunoreactivity in advanced atherosclerosis. The New England journal of medicine. 1991;325:997–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeiher AM, Ihling C, Pistorius K, Schachinger V, Schaefer HE. Increased tissue endothelin immunoreactivity in atherosclerotic lesions associated with acute coronary syndromes. Lancet. 1994;344:1405–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simeone SM, Li MW, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Vascular gene expression in mice overexpressing human endothelin-1 targeted to the endothelium. Physiological genomics. 2011;43:148–60. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00218.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galie N, Manes A, Branzi A. The endothelin system in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovascular research. 2004;61:227–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin LJ. Endothelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension. Life sciences. 2012;91:517–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stow LR, Jacobs ME, Wingo CS, Cain BD. Endothelin-1 gene regulation. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:16–28. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee ME, Dhadly MS, Temizer DH, Clifford JA, Yoshizumi M, Quertermous T. Regulation of endothelin-1 gene expression by Fos and Jun. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:19034–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aitsebaomo J, Kingsley-Kallesen ML, Wu Y, Quertermous T, Patterson C. Vezf1/DB1 is an endothelial cell-specific transcription factor that regulates expression of the endothelin-1 promoter. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:39197–205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wort SJ, Ito M, Chou PC, Mc Master SK, Badiger R, Jazrawi E, et al. Synergistic induction of endothelin-1 by tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma is due to enhanced NF-kappaB binding and histone acetylation at specific kappaB sites. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:24297–305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiter CE, Kim JA, Quon MJ. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate reduces endothelin-1 expression and secretion in vascular endothelial cells: roles for AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt, and FOXO1. Endocrinology. 2010;151:103–14. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitazumi K, Tasaka K. The role of c-Jun protein in thrombin-stimulated expression of preproendothelin-1 mRNA in porcine aortic endothelial cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 1993;46:455–64. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delerive P, Martin-Nizard F, Chinetti G, Trottein F, Fruchart JC, Najib J, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activators inhibit thrombin-induced endothelin-1 production in human vascular endothelial cells by inhibiting the activator protein-1 signaling pathway. Circulation research. 1999;85:394–402. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu RM, Chuang MY, Prins B, Kashyap ML, Frank HJ, Pedram A, et al. High density lipoproteins stimulate the production and secretion of endothelin-1 from cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1994;93:1056–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI117055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earley S, Resta TC. Estradiol attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary endothelin-1 gene expression. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2002;283:L86–93. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00476.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepailleur-Enouf D, Valdenaire O, Philippe M, Jandrot-Perrus M, Michel JB. Thrombin induces endothelin expression in arterial smooth muscle cells. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2000;278:H1606–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.5.H1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He F, Li J, Mu Y, Kuruba R, Ma Z, Wilson A, et al. Downregulation of endothelin-1 by farnesoid X receptor in vascular endothelial cells. Circulation research. 2006;98:192–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200400.55539.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Gonzalez J, Badimon L. The NR4A subfamily of nuclear receptors: new early genes regulated by growth factors in vascular cells. Cardiovascular research. 2005;65:609–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Tiel CM, de Vries CJ. NR4All in the vessel wall. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;130:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pires NM, Pols TW, de Vries MR, van Tiel CM, Bonta PI, Vos M, et al. Activation of nuclear receptor Nur77 by 6-mercaptopurine protects against neointima formation. Circulation. 2007;115:493–500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.626838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonta PI, Matlung HL, Vos M, Peters SL, Pannekoek H, Bakker EN, et al. Nuclear receptor Nur77 inhibits vascular outward remodelling and reduces macrophage accumulation and matrix metalloproteinase levels. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:561–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng H, Qin L, Zhao D, Tan X, Manseau EJ, Van Hoang M, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 regulates VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis through its transcriptional activity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:719–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You B, Jiang YY, Chen S, Yan G, Sun J. The orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 suppresses endothelial cell activation through induction of IkappaBalpha expression. Circulation research. 2009;104:742–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamers AA, Vos M, Rassam F, Marinkovic G, Kurakula K, van Gorp PJ, et al. Bone marrow-specific deficiency of nuclear receptor Nur77 enhances atherosclerosis. Circulation research. 2012;110:428–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanna RN, Shaked I, Hubbeling HG, Punt JA, Wu R, Herrley E, et al. NR4A1 (Nur77) deletion polarizes macrophages toward an inflammatory phenotype and increases atherosclerosis. Circulation research. 2012;110:416–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo YG, Na TY, Yang WK, Kim HJ, Lee IK, Kong G, et al. 6-Mercaptopurine, an activator of Nur77, enhances transcriptional activity of HIF-1alpha resulting in new vessel formation. Oncogene. 2007;26:3823–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhan Y, Du X, Chen H, Liu J, Zhao B, Huang D, et al. Cytosporone B is an agonist for nuclear orphan receptor Nur77. Nature chemical biology. 2008;4:548–56. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ham J, Eilers A, Whitfield J, Neame SJ, Shah B. c-Jun and the transcriptional control of neuronal apoptosis. Biochemical pharmacology. 2000;60:1015–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma C, D’Mello SR. Neuroprotection by histone deacetylase-7 (HDAC7) occurs by inhibition of c-jun expression through a deacetylase-independent mechanism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:4819–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang CZ, Wu SC, Kwan AL, Lin CL, Hwang SL. 6-Mercaptopurine reverses experimental vasospasm and alleviates the production of endothelins in NO-independent mechanism-a laboratory study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:939–49. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nature cell biology. 2002;4:E131–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trejo J, Chambard JC, Karin M, Brown JH. Biphasic increase in c-jun mRNA is required for induction of AP-1-mediated gene transcription: differential effects of muscarinic and thrombin receptor activation. Molecular and cellular biology. 1992;12:4742–50. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng Q, Xia Y. c-Jun, at the crossroad of the signaling network. Protein Cell. 2011;2:889–98. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang XK. Targeting Nur77 translocation. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2007;11:69–79. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin B, Kolluri SK, Lin F, Liu W, Han YH, Cao X, et al. Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell. 2004;116:527–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dschietzig T, Richter C, Pfannenschmidt G, Bartsch C, Laule M, Baumann G, et al. Dexamethasone inhibits stimulation of pulmonary endothelins by proinflammatory cytokines: possible involvement of a nuclear factor kappa B dependent mechanism. Intensive care medicine. 2001;27:751–6. doi: 10.1007/s001340100882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamashita K, Discher DJ, Hu J, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Molecular regulation of the endothelin-1 gene by hypoxia. Contributions of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, activator protein-1, GATA-2, AND p300/CBP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:12645–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.