Abstract

Obesity and overweight are significant problems for children in the US, particularly for Hispanic children. This paper focuses on the children in families of immigrant Hispanic farmworkers, as farm work is the portal though which many immigrants come to the US. This paper (1) describes a model of the nutritional strategies of child feeding in farmworker families; and (2) uses this model to identify leverage points for efforts to improve the nutritional status of these children. In-depth interviews were conducted in Spanish with 33 mothers of 2–5 year old children in farmworker families recruited in North Carolina in 2010–2011. The purposive sample was balanced by farmworker status (migrant or seasonal), child age, and child gender. Interviews were transcribed and translated. Multiple coders and a team approach to analysis were used. Nutritional strategies centered on domains of procuring food, using food, and maintaining food security. The content of these domains reflected environmental factors (e.g., rural isolation, shared housing), contextual factors (e.g., beliefs about appropriate food, parenting style), and available resources (e.g., income, government programs). Environmental isolation and limited access to resources decrease the amount and diversity of household food supplies. Parental actions (parental sacrifices, reduced dietary variety) attempt to buffer children. Use of government food sources is valuable for eligible families. Leverage points are suggested that would change nutritional strategy components and lower the risk of overweight and obesity. Further prospective research is needed to verify the nutritional strategy identified and to test the ability of leverage points to prevent childhood obesity in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: USA, Immigrant, Food security, Acculturation, Social Ecological Theory, Household nutritional strategies

1. Introduction

Obesity and overweight, defined as ≥85th and ≥95th body mass index (BMI) percentile (Barlow, 2007), respectively, are significant problems for young children in the US (Ogden et al., 2014). Among children ages 2–5 years, 14.4% were overweight and 8.4% were obese in 2011–12. Proportions of overweight and obesity consistently vary along lines of race and ethnicity. While 17.4% of non-Hispanic white children were overweight and 3.5% were obese in 2011–12, prevalence rates among Hispanic children were 13.1% overweight and 16.7% obese. These disparities set trajectories for disparities in adult chronic disease and chronic disease risk factors such as obesity and hypertension that are elevated among Hispanics (Daviglus et al., 2012; Lara et al., 2005).

Patterns of and factors underlying the overweight and obesity rates of Hispanic adults and adolescents are the subject of considerable research. Among adults of Mexican heritage, those born in the US are more likely to be obese than those born in Mexico (Creighton et al., 2012; Sanchez-Vaznaugh et al., 2008). Those foreign-born tend to increase in BMI with greater length of US residence, and the effect of length of residence is greatest among those with low education and among women (Sanchez-Vaznaugh et al., 2008), findings consistent with observations of intergenerational differences in dietary patterns. Comparing first and later generations of Mexican-heritage adolescents, the latter show a more obesogenic dietary pattern, with reductions in intakes of fruits, vegetables, rice, and beans, and increases in fast food and soda (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2003; Allen et al., 2007). Adults follow similar dietary patterns over time (Duffey et al., 2008). Together, these studies support the need for attention to diet and other precursors of obesity among children of immigrants. Children of farmworkers constitute a unique group of such children.

Farmworkers in the US comprise a medically-underserved, largely Hispanic population, with high rates of chronic disease (Arcury and Quandt, 2007; Arcury and Marín, 2009). Farmworkers work as hired laborers planting, cultivating, and harvesting crops as needed during the agricultural season. Migrant farmworkers move and establish temporary residence to do farm work, while seasonal farmworkers reside in the same area year round, employed part of the year as farmworkers (USDOL, 2014). Farmworkers can suffer significant economic constraints, compared to workers in other industries. The federal Fair Labor Standards Act exempts farmworkers from the usual provision of overtime wages; those on small farms or farms that employ workers only seasonally are not entitled to the federal minimum wage (USDOL, 2008). While some states have passed more stringent pay standards, including some provision for overtime, many states, particularly those without year-round agriculture, have not (Wiggins, 2009). The farmworker population in the US is estimated to number about 900,000 workers, plus dependents (USDA, 2013). Migrant farmworkers frequently live in grower-provided housing where kitchen and living space is shared among multiple families. About three-quarters of farmworkers are foreign-born, the majority from Mexico; income and educational levels are low (Carroll et al., 2005). Many lack US immigration documents (USDA, 2013). Farmworkers are important beyond their numbers, as farm work is the portal through which many Hispanic immigrants have traditionally first come to the US, before moving into better paying jobs such as construction or manufacturing.

Children of farmworkers face a variety of health problems related to nutrition, due to food insecurity (Borre et al., 2010; Quandt et al., 2004; Quandt et al., 2006) or living in situations with limited cooking or food storage facilities (Kilanowski, 2010; Quandt et al., 2013). Farmworker children live in families that face challenges like many other families in the US, including poverty and rural living. At the same time, they face food-related challenges typical of immigrants, confronting discrimination and ineligibility for some government food safety net programs. The migratory lifestyle of some farmworker families also presents a unique set of challenges for feeding children. Most published data on farmworker children nutritional status indicate significant overweight and obesity prevalence (Borre et al., 2010; Kilanowski and Ryan-Wenger, 2007; Kaiser et al., 2002; Rosado et al., 2013). While a few studies have examined the family and community context of feeding these children (Kilanowski, 2010; Quandt et al., 2013), this literature is limited.

1.1. Conceptual frameworks

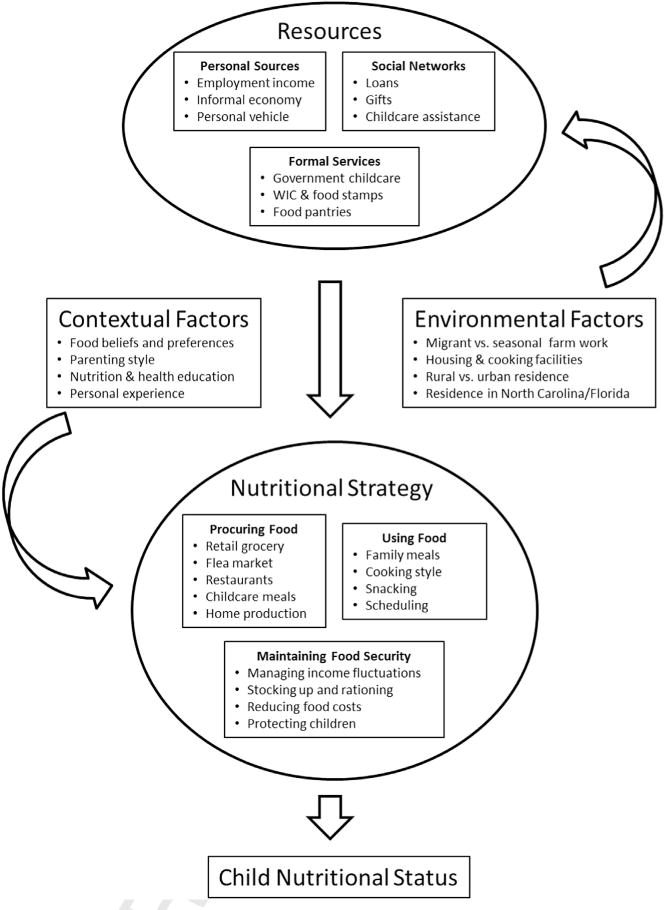

This paper focuses on families with children ages 2–5 years in migrant and seasonal farmworker families in North Carolina. It is grounded, conceptually, on the notion of nutritional strategies (Fig. 1) (Quandt et al., 1998). Households develop nutritional strategies to accomplish the activities necessary for feeding household members. These strategies, which ultimately determine the nutritional status of children and other family members, exist as the intersection of three basic activity domains—procuring food, using food, and maintaining food security—and the resources available to accomplish these activities. Procuring food encompasses the activities surrounding providing food to household members, including shopping for food, dining at restaurants, and home food production. Using food includes activities involved in preparing and serving food, including the scheduling and composition of meals and snacks. Maintaining food security includes activities aimed at maintaining a reliable and adequate supply of food for household members in the face of income fluctuations, food preservation and storage, and using emergency food sources such as food pantries. These three domains of activities are accomplished by drawing on a set of household resources: personal resources (e.g., money) of household members, resources from social networks, and resources from formal programs (e.g., government food benefits). A household’s nutritional strategy is also the product of contextual factors, including the knowledge, beliefs, and values household members use to choose and evaluate potential elements of the nutritional strategy. The resources available to households are influenced by environmental factors, such as the physical environment provided by housing and the neighborhood environment, whether rural or urban.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of nutritional strategy of child feeding in farmworker families.

This study is informed by Social Ecological Theory (Stokols, 1996), which differentiates influences on human health capacity at multiple levels from community to individual. Social Ecological Theory suggests that efforts to prevent negative health outcomes such as childhood obesity or promote positive outcomes such as maintaining a healthy weight must be addressed in a public health context by promoting change in multiple environmental levels, particular in factors that are key determinants of specific health outcomes (“leverage points”), rather than through focusing on personal behavior (Booth et al., 2001). Leverage points that could help modify families’ nutritional strategies to reduce the risk of child overweight and obesity likely exist for each of the components of nutritional strategies. Specifying these leverage points for farmworker children requires first understanding the nutritional strategy itself. The study is also influenced by Family Systems Theory (White et al., 2014), which acknowledges the importance of parent—child interactions, as well as the primary and secondary order systems in families that shape interactions around food (Skelton et al., 2012). Finally, the concept of acculturation is important for understanding dietary behavior of immigrant families. Although cautions on the pitfalls of cultural stereotyping inherent in some research on health behavior change following immigration (Hunt et al., 2004) have substantial merit, the importance of understanding changing behavior in the context of migration into new environmental situations is important.

The paper’s first objective is to articulate a model of nutritional strategies for this population, based on data from in-depth interviews conducted with mothers in farmworker families. The second objective is to use this model to specify key leverage points that can address childhood obesity prevention across multiple components of nutritional strategies. Identifying such leverage points can focus public health practice improving the nutritional status of these children, particularly related to obesity and food insecurity.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This research is part of a prospective study of obesity precursors of young children living in farmworker families. Data for this analysis come from the formative research phase, which used an ethnographic approach, supplementing information from past and ongoing research in the population with in-depth interviews with 33 mothers in farmworker families (Grzywacz et al., 2014; Quandt et al., 2004, 2006).

2.1.1. Recruitment and sample

The sample was balanced on factors hypothesized to affect the approach to and resources available for child feeding: farmworker status (seasonal and migrant), child age (2–3 and 4–5 years), child gender, and eastern and western North Carolina. Farm work in the East focuses on summer crops (e.g., tobacco, cucumbers, sweet potatoes). The West has an agricultural year extending into winter (Christmas trees), and mountains create significant travel and transportation obstacles. Inclusion criteria for mothers were having a resident child aged 2–5 years and a household member employed in agriculture in the previous year. Recruitment was stopped at 33, as saturation was reached (Morse, 1995).

Recruitment used a site-based strategy, identifying sites such as community organizations with access to the target population and enlisting their assistance identifying potential study participants (Arcury and Quandt, 1999). The research team has almost 20 years’ experience conducting community-based participatory research with Latino farmworkers, and has built an extensive network of relationships with organizations serving the farmworker community. Potential participants were referred to study staff by individuals in this network after meetings about the study purpose and inclusion criteria. Sites included Migrant Head Start Program centers, community and migrant clinics, churches with Latino congregations, farmworker camps, and stores (tiendas) patronized by immigrant farmworkers. Study participants were recruited by trained, bilingual study staff. The final sample included 16 women from migrant farmworker families and 17 women from seasonal farmworker families. Six families lived in shared housing. Families had an average of three children in the household. In most cases the farmworker in the household was the participant’s partner; about 40% of the participants reported performing farm work themselves.

2.1.2. Data collection

Data were collected from April 2010 through February 2011, by two bilingual Hispanic interviewers with graduate training in public health and qualitative interviewing experience. Prior to collecting data, interviewers underwent study-specific training that included a thorough review of the interview guide; human subject protections, confidentiality, and procedures for conducting and recording the interview. Each interviewer conducted practice interviews with English-speaking and Spanish-speaking non-farmworker mothers. These were critiqued by the team; additional practice interviews were conducted until interviewers demonstrated mastery of the interview guide. Interviews took place in participants’ homes. Interviewers explained the project and obtained signed informed consent prior to data collection. Participants received a small incentive ($10) after the interview. All procedures were approved by the Wake Forest Health Sciences IRB. A National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained to protect study participants. Interviews ranged from one to 3 h.

The goal of the data collection was to develop a comprehensive understanding of the beliefs, values, and situational factors underlying farmworker families’ practices for feeding their children. A semi-structured interview guide was created to elicit information about the family and household, descriptions of the dwellings and interactions with the surrounding physical and social environment. The interview guide also elicited descriptions of children’s typical eating and family meal patterns, and of how and when food was procured and issues related to food security. The interview guide was edited during the course of the interviews, as new topics emerged.

2.1.3. Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and translated from Spanish to English by a professional service experienced with research interviews in Mexican Spanish. Transcriptions were edited against audio-recordings by interviewers, and distributed to team members (two interviewers and three investigators) as they became available. Group meetings were held to discuss whole transcripts as cases, to identify emerging findings, and to consider new topics for the interview guide. After most of the interviews had been collected, a list of codes was constructed to reflect original and emergent themes and patterns. Definitions for codes were agreed upon, and several transcripts were assigned to team members for coding. These initial coded transcripts were compared, codes clarified, and codes added, as needed. Then each transcript in the dataset was coded by one team member and reviewed by a second. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Atlas ti v6.0 (Scientific Software Development GMBH, Berlin) text management software was used. For the analysis described here, segments for codes related to food beliefs, eating constraints, food sources, food security, parenting style, and child care meals were reviewed after the initial coding. Weekly meetings were held at which the team identified themes and patterns in a particular code, related it to other codes, and constructed matrices of related ideas. If variations by migrant and seasonal farmworker status, child gender, and child age were found, these were noted. When appropriate, separate matrices were constructed based on these variables.

3. Results

Analysis revealed a nutritional strategy reflecting the economic and environmental circumstances of farmworkers, and the beliefs and preferences shaped by the life experiences of these families (Fig. 1). Each of the three primary components—procuring food, using food, and maintaining food security—is described below. Within each section, aspects of resources, contextual factors, and environmental factors are described.

3.1. Procuring food

Most food consumed by these farmworker families is purchased for cooking at home. Walmart is the store preferred by many, as prices are perceived to be lowest of available stores, and it is possible to do “one-stop” shopping because of the non-food items sold. Most participants report that the food selection at Walmart satisfied their needs, particularly because the stores sell many foods desired by immigrants from Mexico. The most significant drawback reported is distance; for many, the nearest Walmart is at least 1 h away.

A few families do all their shopping at other stores, such as Dollar General and Aldi, a discount supermarket chain. Usually these are chosen due to transportation constraints for traveling to Walmart. Flea markets and tiendas are supplementary sources of food for some families, offering particularly desirable items such as tropical produce and traditional types of cornmeal. A few families report patronizing other stores for specific items, particularly meat, based on perceived higher quality than Walmart.

P8: I can’t find everything I want because I want some things that are Mexican. So I go to the Mexican store, but I still don’t find them there sometimes—cactus and other Mexican things. I can’t find everything I want here, but in Florida, I can.

Families report that they do all their grocery shopping once a week, on the weekend, or less frequently, focusing on staples and non-perishables because of infrequency. Overall, price is the most commonly reported factor determining food procurement practices. Indeed, price usually trumps food preferences.

P7: … I go to Food Lion because in Food Lion, they’re having more discounts than in Walmart…. [B]ecause sometimes they put things on sale. That’s why I go there.

Only a few families have gardens, primarily seasonal, not migrant, farmworker families. Gardens are generally small, and a few families keep chickens for both meat and eggs. Despite living in rural communities, available garden space is quite limited, particularly for migrants and others who do not own property.

Families patronize restaurants as special treats for children. A weekend day devoted to grocery shopping and other errands might include a trip to a fast food restaurant, Chinese buffet, or pizzeria, but cost and distance keep restaurant meals to a minimum.

Time is a significant constraint for obtaining food, particularly during the agricultural season when workdays are long, and some growers work every day. Transportation is difficult, particularly for migrant families. Some do not have cars and depend on other families for rides or, rarely, van rides provided by employers. Even families with cars are reluctant to drive for fear of being stopped by law enforcement. Migrant workers from Florida report that shopping is easier there, where communities are less rural and Mexican stores and Walmart are within a few minutes’ walk or drive from home.

3.2. Using food

Women report most of the families’ meals are prepared at home “from scratch,” with minimal use of purchased prepared foods and no cooked-ahead foods. They report that family members, particularly husbands, do not like either canned or frozen foods. Many of the foods mothers prepare for their children are mixtures. Breakfast is yogurt or fruit with cereal or shakes of milk and mashed fruit, or rice with eggs. Lunches often consist of soups of rice, pasta, chicken, and vegetables. The processed-food exceptions are sugar-sweetened beverages (e.g., sodas and Kool-aid) and snack foods, both savory (e.g., chips, ramen noodles) and sweet (e.g., candy, cookies).

Food use is structured by the kitchen facilities available and parent work schedules, especially those of the mother. Migrants who live in camps face challenges for cooking and food storage for perishable foods, as multiple families share stove and refrigerator space.

P27: [W]e lived with another family the whole time, but it’s very hard to live with somebody else because cooking on one stove with two or three families is hard. Before, they’d only give us one refrigerator to share with another family. Think how hard that is to do.

In other cases, food is cooked communally in a camp, and families do not have access to kitchen facilities for additional food storage or preparation. This can affect the quality of food children eat. If the communal food is too spicy, mothers must provide a substitute. One mother purchased a small refrigerator and microwave to store and prepare convenience foods for her son. This child ate primarily ready-to-eat foods (e.g., frozen burritos or biscuits), in contrast to most other children.

For all families, mothers’ work schedules affect the scheduling and content of meals. If mothers work outside the home, food preparation fits around work schedules. It often has to be quick, and fathers do no food preparation. When mothers work, children are in in-home or formal child care. Migrant Head Start, in particular, can provide children with up to three meals a day, so the children do not eat home-prepared meals.

P9: When not a lot of us live together, we make things that take as long as it takes us to cook …. For example, today, what I’m going to give the children is soup and some cheese quesadillas. But everything depends on what we can make on that day because when I don’t work, I can cook things that take longer to make. But when we work, … I’ll end up making rice and eggs, or something fast. Sometimes the children won’t want to eat dinner because they ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner [at Migrant Head Start]. So, when they get here, all they do is drink a glass of milk and eat some [cookies], fruit, or yogurt….

P19: When I have time to cook, I make chicken soup with vegetables. When I get home from work tired, I cook some rice and fried eggs, or chicken noodle soup, or spaghetti. Sometimes, when I stay home from work, I cook some pork with rice so my children will eat it with beans.

Mothers using in-home child care often provide the caregiver with some or all of the food their child eats during the day. They know, or at least assume they know, what the child is eating.

P5: [The babysitter] just gives him food and tortillas. I take him juice, apples, and milk, and that’s all …. Everything I give him here, they give him there because she’s from Guerrero, too …. I ask her about everything she’s doing and she tells me everything – like if he ate the food that was made for him. I have trusted her for a long time.

Some mothers of children in formal child care report little knowledge of what their child eats. Most report that the food is “American” and includes foods like chicken nuggets, pizza, and canned vegetables that they do not serve children at home. Because children are usually bussed to these facilities, parents have little contact with staff to see menus or know about the food provided.

3.2.1. Contextual factors determining food use: approaches to child feeding

Mothers vary in their approach to what and when their children eat, from child-directed to parent-directed. Those who report a more child-directed approach let the child take the lead. They pay considerable attention to fixing food that the child wants and serving it when the child wants to eat.

P5: If he doesn’t want to eat when he gets up at 8:00, he goes and plays. If he’s not hungry, I don’t make him eat. At 9:30 or 10:00, when he wants to eat, I’ll give him a glass of juice and the food that I made for him [earlier] …. If he doesn’t want to eat something we’re having, he’ll ask me for what he does want.

Some who follow this child-directed approach note that they have learned from their child’s child care center or healthcare provider that such an approach can help children learn to recognize sensations of hunger and satiety, thus preventing overeating and obesity.

P2: In the school, they told us that if we made them eat, that we’d make their stomachs be bigger and then, they would start asking for more and more, and that’s not good.

P3: [Health care providers] say [children] should eat a normal amount of what they want. They say the more you give them … they start eating more and more, and that’s why they gain weight.

Other parents follow a more parent-directed approach, even while espousing the more child-directed. One parent, for example, reported not forcing her child to eat, but she reported that she did not allow him milk, juice, or jello until he ate what she gave him. Still others are clearly following a parent-directed approach.

P15: If he doesn’t want [what I have cooked], I tell him that it’s the only thing there is and the only thing he’s going to get to eat. … He might leave it for a little while, but when he comes back, he’ll know that it was the only thing there was to eat.

Other parent-centered behaviors include mothers promising children rewards for eating (e.g., sweets for finishing a meal), or threatening to withhold treats if meals were not finished. Fathers are reported to insist that children eat the family meal, and this is sometimes a source of tension between parents. Overall, the parent-centered approach is more commonly reported.

3.2.2. Contextual factors determining food use: parents’ own experiences

Parental experiences seem to underlie some of their approaches to child feeding. Some react to the restricted choices of their own childhood by allowing their children greater control. Others are wary of food running out, so control what the children are given.

P1: [When I was a child, y]ou ate whatever your mom and dad gave you. I vary their food because I have the chance to give them a little more…. For example, where I lived, my father would tell us, “Today, we’ll eat nopales and tomorrow, we’ll eat nopales because we can’t afford anything else.” … If I give them rice with beans and rice with beans, I’m going to repeat the same history of when I was a little girl.

P5: I [serve food] to him because you can’t waste food since it is expensive, and it can run out just like that. When he wants more, I just give him a little bit. He’ll tell me, “Mom, I don’t want any more.” So, I don’t serve him that much because I know how much he can eat. I don’t want it to be wasted because everything is really expensive with the current situation.

3.2.3. Contextual factors determining food use: mothers’ food beliefs

Two sets of beliefs about child feeding underlie mothers’ practices. The first relates to food as ethnic identity (Fig. 2a) and the second, to food quality (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Taxonomies of food beliefs about child feeding in farmworker families associated with (a) food identity and (b) food quality.

3.2.3.1. Ethnic identity

Mothers contrast “Mexican” and “American” food. They lament their children sometimes preferring American over Mexican foods, suggesting that they need to eat in traditional Mexican ways to share being Mexican with their family. Mothers distinguish Mexican foods by the content of the food and the style in which it is consumed. Mothers report that vegetables should be fresh, and dishes consumed should be prepared fresh for each meal as traditional soups, beans and rice, or other combinations; tortillas made from corn are preferred over flour. Eating style should be structured, as scheduled meals in which food is offered to children for their choice, within the boundaries of traditional foods. Children’s foods are similar to adults’, though less spicy. Mothers report that variety from one family to another in seasoning or other aspects of cooking are also part of Mexican style. The contrast is American food, a category much less developed, but characterized as less flavorful, more uniform, and including packaged or prepared foods and fast food.

3.2.3.2. Food quality

Mothers focus on food quality, particularly on healthfulness of food as judged by its effects on children. “Good” food is Mexican and consists of foods deemed to be health-producing, including meat, fruit and fortified juices, and vegetables. Their health benefits include making children happy, providing energy and enabling them to play, filling children up, and protecting children from the effects of heat. In contrast, “bad” food is non-Mexican and unhealthy. Examples of unhealthy foods are articulated primarily as ingredients (e.g., wheat flour or dough, grease, and oil). Sodas also fit into this category. Such foods are perceived as promoting dental caries, stretching the stomach so the child wants to overeat, ultimately resulting in the child becoming too fat. Despite classifying such foods as “unhealthy”, child feeding descriptions include numerous examples of children given these foods as treats.

3.3. Maintaining food security

Mothers describe a managed process by which, in the face of economic challenges to feeding the family, they have two goals: to be able to provide acceptable meals at all times, and to buffer young children from experiencing deprivation. They accomplish this by managing the household food supply even when there is no economic pressure.

P28: We always have something to eat. That’s the most important thing. Always three meals. There could be no money for something else, but there is money for food.

P21: Sometimes, [lack of money affects the food we buy] for us, but not for [our son]. We prefer for us to have less food as long as he has enough. Sometimes, what we want to buy for ourselves, we don’t. Instead we buy something else that’s cheaper; and then, we buy something that he likes or something that we know is going to be good for him to eat.

When extra money is available, they buy extra non-perishable food or save the money for harder times. They also buy some food in bulk and ration it.

P4: If there’s more money, we try to fill the refrigerator. We buy what will last. Instead of buying a box of oatmeal, I’ll buy two. Instead of buying a bag of beans or rice, I’ll buy two bags of each. And that lasts longer …. I don’t know if you’ve seen those bags of chicken that are the cheapest. What I do is cut that up into little pieces so I can cook a certain amount each week. Sometimes, I perform miracles. I buy a package of beef [and] I slice it and put each piece into a bag. If I buy $20 worth of meat, it lasts me for 20 days or more.

P29: We’re trying to save as much as we can so that, if work runs out or if there isn’t any [money], we’ll have something saved up so we can buy things for our children. Now, we make more salads and try not to eat that much meat – more beans, rice, and soup.

Typically in these families, only the children born in the US are eligible for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. Most mothers whose children get such benefits report always having enough money for food, even if they lack money for other expenses, such as diapers.

When money is tight, some participate in the informal economy, selling tamales or other homemade goods. They also decrease general expenses by deferring purchase of clothing or other material goods. Other belt-tightening measures are aimed at reducing food costs. Families report decreasing the amount of more expensive foods they purchase, particularly meat and fruit, and increasing the amount of less costly substitutes like eggs. Soups and salads are prepared to stretch meats and vegetables by adding pasta or potatoes. Foods that might ordinarily be purchased at grocery stores are purchased at flea markets, where they are less expensive. Fewer processed foods are purchased; for example, some women report making more of their tortillas from scratch when money is tight. As a last resort, families tap into the emergency food system. Migrant families, in particular, report seeking food from churches or food pantries in places where they work.

P7: I try to prepare foods like chicken salad or vegetable salad because it seems that when you prepare those foods, the quantity is greater. So, I try to find a way to prepare food for [the children] so that they can always eat and not go without. When we’re working well, they eat a little more …. But the food does change during the time there’s not enough work. I do everything possible so that they eat the same way. When there isn’t enough money, we [adults] all have to sacrifice a little bit so that the children can eat and so they won’t realize that we don’t have enough money.

4. Discussion

Among US children, Hispanic children ages 2–5 years bear a disparate burden of overweight and obesity (Ogden et al., 2014). Previous research indicates that US-born generations exceed foreign-born in rates of obesity (Creighton et al., 2012; Sanchez-Vaznaugh et al., 2008), as dietary patterns shift toward more processed food including sugar-sweetened beverages and less of the fresh fruit and vegetables characteristics of diets in the country of origin (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2003; Duffey et al., 2008). Farm work is frequently the gateway by which Hispanic immigrant families enter the US economy, so their children constitute an important point for understanding in detail factors that potentiate documented childhood excess weight. Because the physical and social environment of farmworker families, as well as structural realities of farm work, differ from other Latino families in which the circumstances of child feeding might be investigated, closer study of this population is warranted.

The findings of this study are consistent with its theoretical foundations. As predicted by Social Ecological Theory (Stokols, 1996), the broad policy environment shape practices related to procuring food and food use. Farmworker families are constrained by fears of encountering law enforcement while driving. Some southeastern states have established policies for detaining and deporting suspected undocumented immigrants, policies that impact health-related decisions (Martinez et al., 2013). Parental fears that children will be seized by social services keep families close to home (Grzywacz et al., 2014). Governmental policies on farmworker wages and immigrant eligibility for food safety-net programs further constrain family options or provide opportunities, as found in other studies (Sharkey et al., 2013).

The physical environment also shapes nutritional strategies, as seen in other published research. The rural environment presents challenges of distance, lack of public transportation, and higher food costs, as have been found elsewhere (Smith and Morton, 2009; Morris et al., 1992). Alternative food sources, such as flea markets, are used by some families to find preferred foods, though the diversity and use of such alternative food purchase locations is much less extensive than that reported in areas with a predominantly Hispanic population (Sharkey et al., 2012; Dean et al., 2011; Bustillos et al., 2009). Housing conditions, including kitchens, are often crowded, shared, and in poor condition (Arcury et al., 2012; Quandt et al., 2013; Early et al., 2006), limiting food preparation and storage.

Consistent with Family Systems Theory and the concept of acculturation, family structures shape parentechild interactions over food. Many mothers are concerned about preserving their children’s cultural identity through food, in the face of pressures to assimilate to the dominant culture’s way of eating (Kilanowski and Ryan-Wenger, 2007; Himmelgreen et al., 2007; Greder et al., 2012).

However, this study’s findings differ from some existing studies of food among low-income, working families in the US. Research by Devine and colleagues shows that the demands of parental work are associated with lower frequency of home-prepared meals, more individualized meals, fewer family meals, and greater use of fast food and convenience foods (Blake et al., 2011; Jabs and Devine, 2006; Devine et al., 2006). Farmworker families in the present study consume one restaurant meal, at most, per week. Most evening meals are cooked from scratch and eaten as a family, except when children are fed at Head Start; time constraints are dealt with by substituting a quick-cooking ingredient for one requiring a longer preparation time (e.g., eggs for meat) rather than by using fast food or purchased convenience foods. While snack foods are purchased for treats, few other types of convenience foods are reported. While such practices are typically associated with higher dietary quality, this population is at risk of low diet quality because of infrequent grocery shopping, limited and episodic income, lack of garden space, and worry about impending food insecurity. These limit purchase of fresh produce and encourage diets concentrated on energy dense starches and sugars and other less expensive products unlikely to spoil.

The overriding concern of parents is financial; greater income and income security could increase their ability to assure a reliable supply of food and, within constraints of travel in the rural environment, increase ability to purchase healthy foods. However, farmworker income is limited by longstanding federal policies of agricultural exceptionalism (Wiggins, 2009). Most farmworkers in North Carolina and surrounding states are employed by growers who meet criteria that exempt them from paying minimum wage, and all these growers are exempt from paying overtime (USDOL, 2008). In addition, farmworkers are contingent workers so only work when work is available. When it rains or if crops fail, there is no work. Considering such structural constraints on income, identification of other leverage points in family nutritional strategies is needed to reduce the risk of childhood obesity. Table 1 summarizes some of these leverage points, including actions community organizations can take and expected outcomes.

Table 1.

Proposed actions to leverage changes in nutritional strategies to reduce the risk of childhood obesity among children in farmworker families.

| Proposed Actions at leverage points | Expected outcomes of Actions at leverage points, by component of nutritional strategy

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional strategy component

|

Context | Environment | Resources

|

||||

| Procuring food | Using food | Maintaining food security | Personal resources | Formal services | |||

| Promote mobile produce markets to farmworker camps | Increases diversity of food sources | Promotes healthy food use | Addresses problem of distance from food sources | Addresses lack of personal vehicle | Extends existing formal services | ||

| Promote gardens by cooperative resource sheds, distributing tools and inputs (e.g., seeds, plant sets) | Increases diversity of food sources | Promotes healthy food use | Provides food regardless of income | Addresses problem of distance from food sources | Addresses lack of personal vehicle | Addresses lack of personal vehicle | |

| Provide information on healthy eating at low cost restaurants | Reduces consumption of foods with low nutrient ensity | Provides nutrition education specific to US | Improves diet quality within economic constraints | ||||

| Service providers assist eligible families to register for SNAP benefits | Provides steady food source, despite income dips | Maximizes use of SNAP program | |||||

| Encourage food pantries to establish healthy food standards | Improves quality of food distributed | Improves the quality of food distributed | |||||

| Encourage service providers to target food distribution to times families likely to be food insecure | Matches food with timing of food insecurity | Improves schedule of distribution to match need | |||||

| Provide parenting education on using non-food treats for children | Reduces consumption of foods with low nutrient density | Encourages parents not to use unhealthy food as reward | |||||

| Provide family training for child-centered feeding approach | Encourages child food self-regulation | ||||||

Two leverage points serve as exemplars of ways in which household nutritional strategies can prevent childhood obesity. Both focus on expanding the sources for procuring food to promote greater consumption of healthy food. Working with farmworker service providers or public health agencies, mobile markets can be promoted to bring fresh fruits and vegetables to rural farmworker camps. This also addresses the resource constraint, lack of transportation to access food sources. Promoting home or community gardens through cooperative resource sheds for connecting families with tools and sources of inputs such as plant sets (e.g., Cooperative Extension) can also increase the supply of healthy foods and help overcome income constraints on food purchase. Mobile markets and garden promotion have been used in other populations, but largely in urban settings (Zepeda et al., 2014). Expansion to this population can capitalize on preferences for fresh products and pre-migration experiences with produce markets as food sources. The possible value of such options is supported by research in New York City with Hispanic immigrant women (Park et al., 2011). Like the present study, Park and colleagues found that women stressed that “healthy food” was prepared fresh and locally sourced. Survey research showed that presence of farmers markets, but not supermarkets or grocery stores, was associated with more servings per day of fruits and vegetables. A community gardening project with farmworkers in Oregon increased child and adult vegetable intake and improved food security (Carney et al., 2012).

Other leverage points address fewer aspects of the nutritional strategy, but are likely to be important ways to prevent childhood obesity. Providing information to parents to make healthier choices or limit portions in the types of restaurants available in rural communities (predominantly fast food and all-you-can-eat buffets) is another leverage point. Acknowledging these low income parents’ desires to provide something special to their children, but redirecting it from food treats to non-eating activities (e.g., visits to parks) can improve the quality of children’s diets as well as reduce their association of such foods as rewards. Formal services such as the SNAP are important resources in helping farmworker families weather income shortfalls. Many children in farmworker families are eligible for SNAP. Encouraging families to use these benefits and assisting them in registering can reduce child food insecurity and increase money available for more expensive, nutrient-dense foods. Some local churches and farmworker service organizations run food pantries specifically for farmworkers. Like most pantries in the US, these lack standards for the type of food they accept and distribute, though there is increasing call nationally for food pantries to limit their distribution to healthy food (Handforth et al., 2013). Establishing such standards and seeking to include fresh produce could help farmworker families consume healthier food. Pantries targeting times just before migrant families move, when hours of work diminish, or just after they arrive, when moving expenses have taken available cash, could help even out food supplies.

Helping mothers adopt approaches to child feeding that encourage children’s positive eating behaviors could be a key leverage point. Parent-centered practices, where parents exert high demands over what and how much the child eats, are less effective in teaching children to eat only to satiety than a more child-centered approach, where parents set boundaries, but are responsive to the child’s needs and preferences (Tovar et al., 2012). Parent education associated with Head Start could reinforce these ideas. Because such sessions often include fathers, this might assist mothers in being able to provide a consistent parenting approach in child feeding.

This paper expands existing literature by identifying nutritional strategies of child feeding in farmworker families that reflect the experiences and policy, physical, and family environments in which these children are raised. Poverty, seasonal employment, rural isolation, limited environmental resources, and the beliefs and preferences of parents shape the potential for overweight and obesity in farmworker children. Articulating the nutritional strategy model suggests leverage points at the family and community level.

Public health practice focused on initiating changes suggested by these leverage points may help to reduce the burden of obesity and overweight in this vulnerable population. By making reference to the nutritional strategies model, the impact of changes across different domains can be targeted. The use of leverage points can move action from a focus on changing behaviors of individual families to environmental change that can produce population-wide improvements in child health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD059855). The Institute had no involvement in the study conduct, in writing the paper, or in the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Allen ML, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Diamant AL, Hambarsoomian K, Schuster MA. Adolescent participation in preventive health behaviors, physical activity, and nutrition: differences across immigrant generations for Asians and Latinos compared with Whites. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:337–343. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Marín AJ. Latino/Hispanic farmworkers and farm work in the eastern United States: the context for health, safety, and justice. In: Arcury TA, Quandt SA, editors. Latino Farmworkers in the Eastern United States: Health, Safety and Justice. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Delivery of health services to migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:345–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Participant recruitment for qualitative research: a site-based approach to community research in complex societies. Hum Organ. 1999;58:128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Weir M, Chen H, Summers P, Pelletier LE, Galván L, Quandt SA. Migrant farmworker housing regulation violations in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55:191–204. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow SE, Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl. 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Wethington E, Farrell TJ, Bisogni CA, Devine CM. Behavioral contexts, food-choice coping strategies, and dietary quality of a multiethnic sample of employed parents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, Hays NP, et al. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutr Rev. 2001;59(3):S21–S39. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borre K, Ertle L, Graff M. Working to eat: vulnerability, food insecurity, and obesity among migrant and seasonal farmworker families. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:443–462. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustillos B, Sharkey JR, Anding J, McIntosh A. Availability of more healthful food alternatives in traditional, convenience, and nontraditional types of food stores in two rural Texas counties. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney PA, Hamada JL, Rdesinski R, Sprager L, Nichols KR, Liu BY, Shannon J, et al. Impact of a community gardening project on vegetable intake, food security and family relationships: a community-based participatory research study. J Community Health. 2012;37:874–881. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9522-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll DJ, Samardick R, Bernard S, Gabbard S, Hernandez T. Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2001–2002: A Demographic and Employment Profile of United States Farm Workers (Report 9) US Department of Labor, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy; Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton MJ, Goldman N, Pebley AR, Chung CY. Durational and generational differences in Mexican immigrant obesity: is acculturation the explanation? Soc Sci & Med. 2012;75:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Stamler J, et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;308:1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean WR, Sharkey JR, St John J. Pulga (flea market) contributions to the retail food environment of colonias in the South Texas border region. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:705–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farell TJ, Bisogni CA. A lot of sacrifices: work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Ayala GX, Popkin BM. Birthplace is associated with more adverse dietary profiles for US-born than for foreign-born Latino adults. J Nutr. 2008;138:2428–2435. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early J, Davis SW, Quandt SA, Rao P, Snively BM, Arcury TA. Housing characteristics of farmworker families in North Carolina. J Immigr Minority Health. 2006;8:173–184. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-8525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the US: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci & Med. 2003;57:2023–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greder K, Romero de Slowing F, Doudna K. Latina immigrant mothers: negotiating new food environments to preserve cultural food practices and healthy child eating. Fam Consum Serv Res J. 2012;41:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Arcury TA, Trejo G, Quandt SA. Latino mothers’ in farmworker families beliefs about preschool children’s physical activity and play. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014 Feb 13; doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-9990-1. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handforth B, Hennink M, Schwartz MB. A qualitative study of nutrition-based initiatives at selected food banks in the feeding America network. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelgreen D, Romero Daza N, Cooper E, Martinez D. “I don’t make the soups anymore”: pre- to post-migration dietary and lifestyle changes among Latinos living in West-Central Florida. Ecol Food Nutr. 2007;46:427–444. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc Sci & Med. 2004;59:973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J, Devine CM. Time scarcity and food choices: an overview. Appetite. 2006;47:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser LL, Melgar Quiñonez HR, Lamp CL, Johns MC, Sutherlin J, Harwood JO. Food security and nutritional outcomes of preschool-age Mexican-American children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:924–929. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilanowski JF, Ryan-Wenger NA. Health status in an invisible population: carnival and migrant worker children. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29:100–120. doi: 10.1177/0193945906295484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilanowski JF. Migrant farmworker mothers talk about the meaning of food. MCN, Am J Maternal/Child Nurs. 2010;35:330–335. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181f0f27a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, Pinto R, Chavez-Baray S. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review. J Immigr Minority Health. 2013;28 doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4. ([Epub ahead of print]) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris PM, Neuhauser L, Campbell C. Food security in rural America: a study of the availability and costs of food. J Nutr Educ. 1992;24:52Se58S. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. The significance of saturation. Qual Health Res. 1995;5:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Quinn J, Florez K, Jacobson J, Neckerman K, Rundle A. Hispanic immigrant women’s perspective on healthy foods and the New York City retail food environment: a mixed-method study. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Bell RA. Self-management of nutritional risk among older adults: a conceptual model and case studies from rural communities. J Aging Stud. 1998;12:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Early J, Tapia J, Davis JD. Household food security among Latino farmworkers in North Carolina. Public Health Reports. 2004;119:568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Shoaf JI, Tapia J, Hernandez-Pelletier M, Clark HM, Arcury TA. Experiences of Latino immigrant families in North Carolina help explain elevated levels of food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr. 2006;136:2638–2644. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Summers P, Bischoff WE, Chen H, Wiggins MF, Spears CR, Arcury TA. Cooking and eating facilities in migrant farmworker housing in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e78–e84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JI, Johnson SB, McGinnity KA, Cuevas JP. Obesity among Latino children within a migrant farmworker community. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3 Suppl. 3):S274–S281. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Sánchez BN, Acevedo-Garcia D. Differential effect of birthplace and length of residence on body mass index (BMI) by education, gender and race/ethnicity. Soc Sci & Med. 2008;67(8):1300–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Johnson CM. Use of vendedores (mobile food vendors), pulgas (flea markets), and vecinos o amigos (neighbors or friends) as alternative sources of food for purchase among Mexican-origin households in Texas border colonias. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:705–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Nalty CC. Child hunger and the protective effects of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and alternative food sources among Mexican-origin families in Texas border colonias. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton JA, Buehler C, Irby MB, Grzywacz JG. Where are family theories in family-based obesity treatment?: conceptualizing the study of families in pediatric weight management. Int J Obes Lond. 2012;36:891–900. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Morton LW. Rural food deserts: low-income perspectives on food access in Minnesota and Iowa. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar A, Hennessy E, Pirie A, Must A, Gute DM, Hyatt RR, Economos CD, et al. Feeding styles and child weight status among recent immigrant mother-child dyads. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2012;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor. Who Are Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers? Employment and Training Administration. USDOL. 2014 (accessed 7.3.14.). http://www.doleta.gov/programs/who_msfw.cfm.

- US Department of Labor. Agricultural Employers Under the Fair Labor Standards ACT (FLSA) Fact Sheet #12. 2008 (accessed 9.10.14.). http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs12.pdf.

- USDA. Farm Labor (December 2013). National Agricultural Statistics Service. USDA. 2013 (accessed 3.6.14.). http://usda01.library.cornell.edu/usda/current/FarmLabo/FarmLabo-12-05-2013_revision.pdf.

- White JM, Klein DM, Martin TF. Family Theories. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins MF. Farm labor and the struggle for justice in the eastern United States. In: Arcury TA, Quandt SA, editors. Latino Farmworkers in the Eastern United States. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda L, Reznickova A, Lohr L. Overcoming challenges to effectiveness of mobile markets in US food deserts. Appetite. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.026. ([Epub ahead of print]) [DOI] [PubMed]