Abstract

Background & Aims

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is commonly treated with swallowed (topical) corticosteroids (tCS). However, few factors have been described that predict outcomes of steroid therapy. We aimed to identify factors associated with non-response to tCS and report outcomes of second-line treatment for patients with steroid-refractory EoE.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study, using the University of North Carolina

EoE Clinicopathologic Database to identify patients who received tCS for EoE from 2006 through 2013. Demographic, symptom, endoscopic, and histologic data were extracted from medical records. Immunohistochemistry was performed on archived biopsies. Responders and non-responders to tCS were compared.

Results

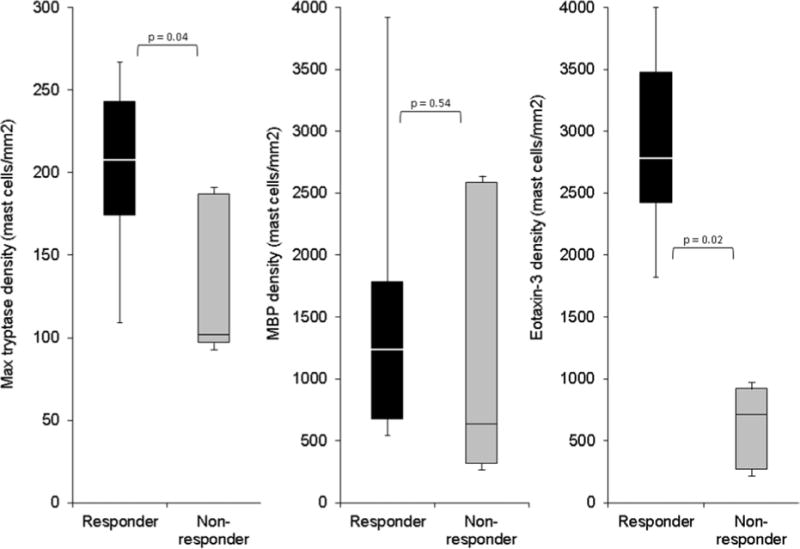

Of 221 patients with EoE who received tCS, 71% had endoscopic improvement, 79% had symptomatic improvement, and 57% had histologic response (<15 eosinophils/high-power field). After multivariate logistic regression, esophageal dilation at the baseline examination predicted nonresponse (odds ratio [OR], 2.9; 95% CI, 1.4–6.3), and abdominal pain predicted response (OR for nonresponse, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12–0.83); no other clinical features were predictive. Based on immunohistochemical analysis, higher levels of tryptase (244 mast cells/mm2 vs 157, P=.04) and eotaxin-3 (2425 cells/mm2 vs 239, P=.02) were associated with steroid response, but levels of major basic protein were not. Among 27 steroid-refractory patients, a mean of 2 additional therapies were tried; only 48% of the patients eventually responded to any second-line therapy.

Conclusions

Based on a retrospective analysis of a large group of patients with EoE, only 57% have a histologic response to steroid therapy. Baseline esophageal dilation and decreased levels of mast cells and eotaxin-3 predicted which patients would not respond to therapy; immunohistochemistry might therefore be used to direct therapy.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, corticosteroids, refractory, therapy, biomarkers

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, immune-mediated disorder of the esophagus defined by esophageal dysfunction and eosinophil infiltration into the esophageal mucosa in the absence of competing causes of esophageal eosinophilia.1–3 Swallowed (“topical”) corticosteroids (tCS) are routinely used for treatment.4–9 While these medications successfully treat the majority of patients, a substantial minority of patients will have incomplete response.4,7

The predictors of successful steroid treatment have not been well explored. Whether demographic factors or endoscopic phenotypes of EoE10 are associated with treatment outcomes is unknown. Similarly, evidence supports a role for food and environmental allergies in the development of EoE,11–14 but the outcomes of patients with and without allergies have not been systematically explored. While the role of biomarkers in EoE is actively being explored, their utility for predicting treatment response has not been established.15–18 We have previously shown that immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for major basic protein (MBP), tryptase, and eotaxin-3 can discriminate EoE from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),19,20 though it is unknown whether these markers at baseline could predict response to tCS.

The aims of this study were to determine the frequency of non-response to topical steroid treatment in EoE and to identify clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and immunohistochemical predictors of response. Further, we sought to describe the success of second line therapies in patients refractory to tCS.

Methods

Patients, data sources, and outcomes

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of patients at University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals from 2006–2013. Patients with EoE of any age were identified from the UNC EoE Clinicopathologic Database.20,21 For inclusion, patients had to have EoE by consensus guidelines1–3 including a diagnostic endoscopy while on high dose proton pump inhibitor and undergo treatment with swallowed tCS (fluticasone or budesonide for all study participants). In our practice, the first line course of tCS is either budesonide (0.5–1 mg twice daily, depending on patient age, with the aqueous formula mixed into a slurry with 5g of sucralose)5,9 or fluticasone (440–880 mcg twice daily, depending on patient age).4,7 Patients are instructed not to eat or drink anything for 60 minutes after swallowing the medication. Patients were typically treated for approximately 8 weeks prior to reassessment with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Further endoscopies were dependent on patient symptoms and response to therapy, typically occurring at 8 week intervals until control of disease.

Data were abstracted from the UNC electronic medical record. Using standardized data collection tools, we recorded patient demographics, symptoms, comorbidities, baseline and follow-up endoscopy findings, baseline and follow-up eosinophil counts on esophageal biopsy, and therapeutic regimen. Patient symptoms were assessed prior to the diagnostic endoscopy and before treatments such as dilation or steroids. Eosinophil counts were previously determined for clinical purposes and were recorded as the maximum number of eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf; hpf size = 0.24mm2) from pathologist review. Outcomes included symptom response (dichotomous patient-reported subjective improvement [yes/no]), endoscopic improvement (abstracted from endoscopy reports based on endoscopist’s global assessment), and post-treatment eosinophil count. Because there is no consensus on the histologic cut-point to determine treatment response,3,22 an eosinophil count <15 eos/hpf was considered a response to therapy for the purpose of this analysis and was the main histologic outcome. We used the term “complete response” to describe only those patients with elimination of esophageal eosinophilia (0 eos/hpf). Patients who did not have a repeat endoscopy but who had clinical follow-up data with symptom outcomes were included in the symptom outcomes only.

To assess second-line treatment in steroid non-responders, we identified steroid refractory patients. They were defined as those who had >30 eos/hpf on repeat endoscopy and any one of the following: failure to have a symptomatic response, failure to have an endoscopic response, or requirement for esophageal dilation at presentation. A cutoff of 30 eos/hpf minimized misclassification occurring near the diagnostic cutpoint of 15 eos/hpf and to isolate those with more severe disease. Dilation was included because there were a group of patients with persistent esophageal eosinophilia but relief of symptoms attributable to dilation.

Immunohistochemistry Staining

IHC was performed for MBP, eotaxin-3, and tryptase on a subset of randomly selected patients with baseline tissue blocks available using previously described methodology.19,20 Briefly, IHC was performed using a high volume automated system (Bond Autostainer, Leica Microsystems, Norwell, MA) according to the standard protocol. Slides were deparaffinized with xylene and antigen retrieval was achieved with pepsin (20 mins) for MBP, and with Bond-Epitope Retrieval solution (citrate, pH = 6, AR9961) for eotaxin-3 and tryptase. Slides were incubated with the primary antibody of interest, incubated with a peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody, stained with a diaminobenzidine chromogen, and then counterstained with hematoxylin. The primary antibodies included: anti-MBP (mouse, clone BMK 13, 1:100 dilution; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK and Raleigh, NC); anti-eotaxin-3 (goat, no. 500-P156G, 1:100 dilution; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and a mouse anti-human mast cell tryptase primary antibody (Clone AA1; #M7052; 1:3000 dilution; Dako, Carpinteria, CA). The slides were digitized and viewed with Aperio ImageScope (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA). The maximum density of stain-positive cells in the esophageal epithelial layer, measured in cells/mm2, was determined after examination of five microscopy fields.

Data Analysis

All data was analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC). Bivariate analyses were performed with chi-square testing for categorical variables. Because all continuous variables were non-normally distributed, the Wilcoxon two-tailed t approximation was used.

For construction of logistic regression models to predict steroid non-response, all variables at the p<0.2 level on bivariate testing were included with the exception of esophageal narrowing. Narrowing was excluded in favor of dilation because the two variables represent related features of the esophagus, but dilation has less subjectivity. Stepwise reduction was performed until only variables at the p<0.05 level remained. The main effects model was then adjusted for variables which influenced treatment response but which did not reach statistical significance. Odds ratios derived from the main effects model and from the adjusted model are reported. This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 221 patients with EoE who were treated with a tCS during their course of care. The mean age was 25.6 ± 18 years, 83% were white, and 70% were male (Table 1). The predominant symptom at the time of diagnosis was dysphagia (70%). Prior to diagnosis, patients had symptoms for an average of 7.5 ± 9.3 years, and co-existing allergic illness was common (58%). One-quarter required dilation at initial endoscopy. Baseline eosinophil count was 79 ± 66 eos/hpf.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population and Steroids Responders/Non-responders

| All Participants (n = 221)* |

<15 eos/hpf on steroids (n = 108) |

≥15 eos/hpf on steroids (n = 81) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years ± SD (range) | 25.6 ± 18.0 (0.6, 78.3) |

28.0 ± 18.9 (1.4, 78.3) |

24.9 ± 17.0 (0.6, 72.2) |

0.23 |

| Adults ≥ 18 years, n (%) | 129 (58) | 64 (59) | 53 (65) | 0.39 |

| Males, n (%) | 155 (70) | 77 (71) | 56 (69) | 0.75 |

| Whites, n (%) | 184 (83) | 95 (88) | 63 (78) | 0.06 |

| Symptoms (n, %) | ||||

| Dysphagia | 152 (70) | 75 (70) | 59 (75) | 0.49 |

| Food impaction | 70 (32) | 35 (33) | 26 (33) | 0.98 |

| Heartburn | 88 (41) | 47 (44) | 28 (35) | 0.24 |

| Chest pain | 25 (12) | 16 (15) | 6 (8) | 0.12 |

| Abdominal pain | 40 (18) | 24 (22) | 6 (8) | 0.007 |

| Nausea | 24 (11) | 13 (12) | 5 (6) | 0.18 |

| Vomiting | 62 (29) | 31 (29) | 19 (24) | 0.43 |

| Failure to thrive | 33 (15) | 19 (18) | 12 (15) | 0.62 |

| Years of symptoms before diagnosis, mean ± SD (range) | 7.5 ± 9.3 (0.0, 53.0) |

9.2 ± 10.6 (0.0, 53.0) |

6.5 ± 7.9 (0.0, 45.0) |

0.12 |

| Allergic diseases (n, %) | ||||

| Atopic Illness | 101 (47) | 47 (44) | 41 (51) | 0.32 |

| Asthma | 56 (26) | 26 (24) | 22 (28) | 0.62 |

| Food allergy | 57 (29) | 31 (31) | 20 (26) | 0.47 |

| Any allergic disease | 125 (58) | 60 (56) | 47 (59) | 0.71 |

| Endoscopic findings (n, %) | ||||

| Normal | 22 (10) | 10 (9) | 5 (6) | 0.43 |

| Rings | 101 (46) | 47 (44) | 46 (57) | 0.08 |

| Stricture | 45 (20) | 19 (18) | 22 (27) | 0.12 |

| Narrowing | 38 (17) | 13 (12) | 23 (28) | 0.005 |

| Linear furrows | 110 (50) | 56 (52) | 50 (62) | 0.20 |

| White plaques | 61 (28) | 31 (29) | 26 (32) | 0.64 |

| Decreased vascularity | 58 (26) | 30 (28) | 27 (33) | 0.43 |

| Crêpe-paper mucosa | 13 (6) | 7 (7) | 6 (7) | 0.82 |

| Hiatal hernia | 21 (10) | 9 (8) | 8 (10) | 0.71 |

| Dilation performed | 55 (25) | 20 (19) | 30 (37) | 0.006 |

| Maximum eosinophil count, mean ± SD (range) | 79 ± 66 (15, 469) |

76 ± 65 (15, 430) |

75 ± 56 (15, 333) |

0.85 |

28 patients declined repeat endoscopy and 4 patients did not have esophageal biopsies during their follow-up EGD; they are only included in non-endoscopic outcomes.

Budesonide was the most common therapy (63%) with the remainder treated with fluticasone (Table 2). The average total daily dose of budesonide was 1686 mg (2077±576 mg in patients ≥18, 1194±474 mg in patients <18), and fluticasone was 1100 mg (1412±513 mg in patients ≥18, 566±296 mg in patients <18).

Table 2.

Steroid Treatment and Response

| All Participants (n = 221)* |

<15 eos/hpf on steroids (n = 108) |

≥15 eos/hpf on steroids (n = 81) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of topical steroid, n (%) | 0.48 | |||

| Fluticasone | 81 (37) | 27 (25) | 24 (30) | |

| Budesonide | 140 (63) | 81 (75) | 57 (70) | |

| Total daily dose of topical steroid, mean mcg ± SD | ||||

| Fluticasone | 1100 ± 604 | 1279 ± 567 | 1247 ± 641 | 0.89 |

| Budesonide | 1686 ± 690 | 1722 ± 671 | 1654 ± 705 | 0.49 |

| Steroid therapy max eosinophil count, mean ± SD (range) | 27 ± 40 (0, 200) | 2 ± 3 (0, 14) | 61 ± 41 (15, 200) | <0.0001 |

| % change in eos, mean ± SD (range) | −51 ± 79 (−100, 355) | −97 ± 6 (−100, −73) | 10 ± 89 (−88, 355) | <0.0001 |

| Response to tCS, n (%) | ||||

| Symptom response | 150 (79) | 82 (87) | 38 (60) | <0.0001 |

| EGD response | 137 (71) | 99 (92) | 34 (42) | <0.0001 |

| Endoscopy Findings on Steroid Therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Normal | 45 (23) | 38 (35) | 7 (9) | <0.0001 |

| Rings | 78 (41) | 37 (35) | 40 (49) | 0.052 |

| Stricture | 37 (20) | 9 (9) | 26 (32) | <0.0001 |

| Narrowing | 30 (16) | 8 (8) | 21 (26) | 0.0008 |

| Linear furrows | 73 (39) | 19 (18) | 53 (65) | <0.0001 |

| White plaques | 37 (20) | 7 (7) | 30 (37) | <0.0001 |

| Decreased vascularity | 46 (24) | 18 (17) | 28 (35) | 0.007 |

| Crêpe-paper mucosa | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.26 |

| Dilation performed | 46 (24) | 12 (12) | 31 (38) | <0.0001 |

| Candida present | 10 (5) | 8 (8) | 2 (3) | 0.12 |

28 patients declined repeat endoscopy and 4 patients did not have esophageal biopsies during their follow-up EGD; they are only included in non-endoscopic outcomes.

Response to steroid therapy and predictors of non-response

Repeat endoscopy to assess the effect of steroid therapy was performed on 193 (87%) patients, and 137 (71%) had an improved endoscopic appearance. Of the 193 repeat endoscopies, 189 (98%) included biopsies. Those biopsies demonstrated that 108 (57%) patients had <15 eos/hpf, while the remaining 81 (43%) showed ≥15 eos/hpf and were considered non-responders. Additionally, follow-up symptom data were available on 190 patients, 150 of whom (79%) had a symptomatic response to tCS.

Responders did not differ from non-responders for the majority of presenting symptoms, symptom duration prior to diagnosis, rates of allergic illness, or baseline eosinophil counts (Table 1). However, non-responders had baseline EGDs that more frequently showed esophageal narrowing (28% vs 12, p=0.005) and required dilation (37% vs 19, p=0.006). There was no significant difference in the type or dose of steroid used (Table 2).

On multivariate logistic regression, after adjustment for age, allergic disease, and baseline eosinophil count, only the need for dilation predicted steroid non-response (OR 2.9, 95% CI [1.4–6.3]) while abdominal pain at presentation was associated with therapeutic response (OR for non-response 0.31, 95% CI [0.12–0.83]) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of Non-Response to TCS from Multivariate Logistic Regression

| Main Effects Model OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI]* | |

|---|---|---|

| White Race | 0.42 [0.18–0.97] | 0.54 [0.22–1.29] |

| Abdominal Pain | 0.32 [0.12–0.85] | 0.31 [0.12–0.83] |

| Dilation Performed | 2.4 [1.2–4.8] | 2.9 [1.4–6.3] |

Adjusted for age, baseline eosinophil count, and known allergic disease; OR > 1.0 indicates increased odds of not responding to steroids.

Immunohistochemical Markers for Predicting Response to TCS

To assess the utility of MBP, eotaxin-3, and tryptase for predicting response to tCS, 40 baseline esophageal biopsies were randomly selected with 20 from patients who responded (<15 eos/hpf) and 20 who did not. The characteristics of this patient subset were similar to the overall study population, with the exception of post-treatment eosinophil count. Responders were 31 ± 15 years, 70% were male, 95% were white, the baseline maximum eosinophil count was 80 ± 64 eos/hpf, and the post-treatment count was 3 ± 4. The non-responders were 31 ± 11 years, 70% were male, all were white, the baseline eosinophil count was 97 ± 86 eos/hpf, and the post treatment count was 75 ± 21. On IHC staining, the median tryptase density was greater in steroid responders (244 mast cells/mm2 vs 157, p=0.04) as was eotaxin-3 density (2425 cells/mm2 vs 239, p=0.02). MBP density did not differ between the two groups (1064 cells/mm2 in responders vs 1715 in non-responders, p=0.54) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Predicting steroid response with baseline IHC staining for tryptase, MBP, and eotaxin-3. For this box and whiskers plot, the horizontal line represents the median, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the whiskers end at the maximum and minimum values. Steroid responders (<15 eos/hpf) are in black bars, and non-responders (≥ 15 eos/hpf) are in light gray bars.

Second-line Therapies in Refractory Patients

Of the 57 refractory patients identified, 27 (47%) underwent subsequent second-line therapy. The 30 patients not receiving second-line therapy either declined or were lost to follow up. In this refractory group (mean age 26, 52% male, 74% white), baseline eosinophil count was 95±77 eos/hpf and after steroid therapy was 85±32. A mean of 2 (range 1–7) additional therapies were prescribed after failing tCS (Table 4). The most common was dietary therapy using a targeted or six food elimination diet. This was tried by 16 (59%) of the 27 patients who received second line therapies and resulted in response (<15 eos/hpf) in six (38%). No treatment resulted in response in more than half of patients, and the overall rate of response was 48%. After treatment, these patients achieved an average esophageal eosinophil count of 26±26 eos/hpf. Notably, seven (26%) of these patients acknowledged medication non-compliance. The rate of successful second-line therapy did not differ significantly between patients who endorsed non-compliance and those who did not (43% vs 50%, p=0.74).

Table 4.

Second-Line Therapies for Refractory Patients (n = 27)

| Therapy (n receiving) | Responded with < 15 eos (n, %) |

|---|---|

| Dietary (16) | 6 (38) |

| Increased dose (14) | 2 (14) |

| Changed topical agent (7) | 2 (29) |

| Singular (7) | 1 (14) |

| Prednisone (5) | 1 (20) |

| Ciclesonide (3) | 0 (0) |

| Compounded budesonide (2) | 1 (50) |

| Ketotifen (1) | 0 (0) |

| 6 MP (1) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 13 (48) |

Serial esophageal dilation was used adjunctively in the treatment of refractory patients. Of 57 refractory patients, 19 (33%) underwent dilation at their diagnostic EGD. Fifty-three underwent a second EGD with 25 (47%) receiving dilation at that visit. Of 36 undergoing a third EGD, 18 (50%) were dilated, and of 26 undergoing a fourth EGD 16 (62%) received dilation. The majority of refractory patients required at least one dilation (31, 53%), and among the 53 patients undergoing two or more EGDs, 23 (46%) required 2 or more dilations. In this population, dilation was safe with no esophageal perforations reported.

Discussion

While tCS remain the primary pharmacologic treatment for EoE,4,17,23 little is known about clinical or biomarker predictors of response, and there are few data on second-line treatments in steroid-refractory patients. In this study of a large cohort of EoE patients treated with tCS, we examined predictors of response to steroid therapy in EoE. There are several notable findings. First, histologic non-response to tCS was common. More than 40% of patients had persistent esophageal eosinophilia defined as ≥15 eos/hpf, despite recommended doses of corticosteroids. This highlights the need for both improved topical steroid formulations and novel non-steroid agents to more effectively treat EoE. This rate of steroid non-response is similar to past randomized studies (38–50% for fluticasone; 13–36% for budesonide), taking into account different treatment endpoints.4,5,7,9,24,25

Our refractory patients were difficult to treat with dietary and second-line pharmacologic therapies, with less than half responding, even after multiple second line therapies. However, this population was small, and results should be interpreted with caution. The rate of medication non-adherence in our refractory patient population reinforces the importance of confirming that patients are taking and administering tCS properly. However, this non-compliance may also reflect patients with truly refractory disease discontinuing medications from which they do not receive benefit. Because we cannot differentiate these two groups (those whose non-compliance resulted in persistent disease and those who self-discontinued their medications due to a lack of effect) we included all non-responders to produce the most conservative estimates.

We found few clinical, endoscopic, or histologic predictors of steroid non-response. After multivariate analysis, patients who had abdominal pain at baseline were more likely to respond, while those requiring dilation at baseline were less likely to respond. The association of abdominal pain and improved clinical response is a new finding. One possible interpretation is that EoE may have different phenotypes, and the abdominal pain phenotype is easier to treat. It is also possible that the abdominal pain reflects an increased level of local inflammation that is more amenable to treatment with steroids. The underlying mechanism causing abdominal pain is not clear and merits further investigation.

The finding that the need for dilation at the time of disease presentation correlates to poor clinical outcomes is important. Dilation may be a proxy for the fibrostenotic phenotype of EoE, corresponding to later stage or more advanced disease,10,26 or it may correlate with a more aggressive form of the disease as our groups did not differ on symptom duration prior to diagnosis. Alternatively, dilation at baseline may decrease the efficacy of tCS by hastening clearance of the medication from the esophagus due to relief of distal obstruction.

There are relatively few data to help contextualize these results. Two small randomized controlled trials of steroid therapy in pediatric patients identified allergies and greater age, height, and weight as predictors of failure of steroid therapy.4,27 The only previous study of predictors of successful steroid therapy in adults was published in abstract form. On multivariate analysis, predictors of non-response were older age, the absence of food impaction, furrows, and dilation.28 While these were preliminary data, the finding that the need for baseline dilation predicts non-response is consistent with our findings. Clinicians should now recognize that strictures are a poor prognostic factor, and can use this finding to guide both patient counseling and plan of care.

A unique aspect of this study is the assessment of immunohistochemical predictors of steroid response. Those patients with high tissue levels of tryptase and eotaxin-3 at baseline were more likely to respond to tCS. This finding potentially opens new avenues of investigation, both to confirm these results and to understand the mechanisms. Previous research has shown that these biomarkers can help differentiate EoE from GERD,20 and eotaxin-3 levels have been shown to correlate with eosinophil counts and to decrease with steroid therapy.15 As of now, it is only possible to speculate whether patients with EoE and high mast cell levels might represent a tCS-responsive EoE sub-phenotype. If confirmed, these biomarkers may help differentiate steroid non-responders earlier in their course of care, allowing patients to be transitioned to alternate therapies earlier.

This study has several weaknesses. Because it is retrospective, not all outcomes are available in all patients and because some variables relied on chart review, there is the possibility of a non-differential classification bias. In addition, we rely on non-validated, binary (yes/no) measures of symptom and endoscopic response. This technique provided limited response detail in terms of individual symptoms and introduced the possibility of bias. While no validated measures of symptomatic or endoscopic response existed during the study time frame, and we have employed similar measures in other studies,29 interpretation of symptomatic and endoscopic outcomes should be done with caution. In addition, we chose <15 eos/hpf as a cutoff for histologic response because it is consistent with the histologic cutpoint of ≥15 eos/hpf which defines EoE.1–3 However, there is no consensus on what eosinophil count should be used to define response to therapy, and current guidelines do not define refractory EoE.3,30 We also rely on a specific definition of refractory disease with a cutpoint of ≥30 eos/hpf with in combination with clinical factors to minimize misclassification occurring near the diagnostic cutpoint of 15 eos/hpf and to better identify those with severe disease.

This study also has multiple strengths. This is one of the largest cohorts reported to have treatment with tCS and follow-up, and has the power to assess predictors of steroid response. Additionally, we feel these response rates represent the real-world clinical effectiveness of these medications, rather than the efficacy measures reported in clinical trials, and therefore can be used by practitioners to inform patients of expected outcomes. Moreover, the use of baseline IHC staining to predict treatment outcomes provides novel findings and opens new areas of study.

In conclusion, while the majority of patients benefited from topical steroid therapy, non-response was common. For those who did not respond to steroid therapy, less than half were able to achieve disease response with other second-line therapies. There were few clinical, endoscopic, or histologic predictors of non-response, but the need for dilation at baseline was a strong independent predictor. Additionally, high esophageal tissue levels of eotaxin-3 and mast cells at baseline predicted treatment response, but this intriguing finding requires prospective confirmation before it can be adopted clinically.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was supported, in part, by NIH awards T32DK007634 (WAW), P30DK034987 (WAW), K24DK100548 (NJS), and K23DK090073 (ESD)

Abbreviations

- EoE

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- eos/hpf

eosinophils per high powered field

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MBP

major basic protein

- tCS

topical corticosteroids

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Dellon has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Meritage, and is a consultant for Aptalsis, Novartis, Receptos, and Regeneron. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions (all authors approved the final draft): Asher Wolf: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, Cary Cotton: acquisition of data, technical expertise, critical review of the manuscript, Daniel Green: acquisition of data, critical review of the manuscript, Julia T. Hughes: acquisition of data, critical review of the manuscript, John T. Woosley: study supervision, critical revision of the manuscript, Nicholas J. Shaheen: study supervision, critical revision of the manuscript, Evan S. Dellon: study concept and design, data interpretation, study supervision, critical revision of the manuscript

References

- 1.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–92. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. quiz 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–429.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–1537.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;10:742–749.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellon ES. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1066–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O, et al. Viscous topical is more effective than nebulized steroid therapy for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:321–324.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013:586–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, et al. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:83–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moawad F, Veerappan G, Lake J, et al. Correlation between eosinophilic oesophagitis and aeroallergens. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurrell JM, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia varies by climate zone in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:698–706. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothenberg ME. Biology and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1238–1249. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konikoff MR, Blanchard C, Kirby C, et al. Potential of blood eosinophils, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, and eotaxin-3 as biomarkers of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;4:1328–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu TX, Sherrill JD, Wen T, et al. MicroRNA signature in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, reversibility with glucocorticoids, and assessment as disease biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1064–1075.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldwell JM, Blanchard C, Collins MH, et al. Glucocorticoid-regulated genes in eosinophilic esophagitis: a role for FKBP51. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:879–888.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4033. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, et al. Tryptase staining of mast cells may differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;106:264–271. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, et al. Diagnostic utility of major basic protein, eotaxin-3, and leukotriene enzyme staining in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1503–1511. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirano I. Therapeutic end points in eosinophilic esophagitis: is elimination of esophageal eosinophils enough? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;10:750–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Straumann A, Degen L, Felder S, et al. Budesonide As Induction Treatment for Active Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adolescents and Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study (Bee-I Trial) Gastroenterology. 2008;134:A–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta SK, Collins MH, Lewis JD, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Budesonide Suspension (OBS) in Pediatric Subjects With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): Results From the Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled PEER Study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(supplement 1):s179. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Increases Risk for Stricture Formation, in a Time-Dependent Manner. Gastroenterology. 2013:1230–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Clinical and immunopathologic effects of swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;2:568–575. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moawad F, Albert D, Heifert T, et al. Predictors of Non-Response to Topical Steroids Treatment in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(Supplement 1):s14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf WA, Jerath MR, Sperry SL, et al. Dietary Elimination Therapy is an Effective Option for Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.12.034. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukkada VA, Furuta GT. Management of Refractory Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Digestive Diseases. 2014;32:134–138. doi: 10.1159/000357296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]