Abstract

Introduction

We sought to derive literature-based summary estimates of readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality among patients discharged alive from the ICU.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to March 2013, as well as the reference lists in the publications of the included studies. We selected cohort studies of ICU discharge prognostic factors that in which readmission to the ICU or hospital mortality among patients discharged alive from the ICU was reported. Two reviewers independently abstracted the number of patients readmitted to the ICU and hospital deaths among patients discharged alive from the ICU. Fixed effects and random effects models were used to estimate the pooled cumulative incidence of ICU readmission and the pooled cumulative incidence of hospital mortality.

Results

The analysis included 58 studies (n = 2,073,170 patients). The majority of studies followed patients until hospital discharge (n = 46 studies) and reported readmission to the ICU (n = 46 studies) or hospital mortality (n = 49 studies). The cumulative incidence of ICU readmission was 4.0 readmissions (95% confidence interval (CI), 3.9 to 4.0) per 100 patient discharges using fixed effects pooling and 6.3 readmissions (95% CI, 5.6 to 6.9) per 100 patient discharges using random effects pooling. The cumulative incidence of hospital mortality was 3.3 deaths (95% CI, 3.3 to 3.3) per 100 patient discharges using fixed effects pooling and 6.8 deaths (95% CI, 6.1 to 7.6) per 100 patient discharges using random effects pooling. There was significant heterogeneity for the pooled estimates, which was partially explained by patient, institution and study methodological characteristics.

Conclusions

Using current literature estimates, for every 100 patients discharged alive from the ICU, between 4 and 6 patients on average will be readmitted to the ICU and between 3 and 7 patients on average will die prior to hospital discharge. These estimates can inform the selection of benchmarks for quality metrics of transitions of patient care between the ICU and the hospital ward.

Introduction

Transitions of patient care between providers are vulnerable periods in health care delivery that expose patients to preventable errors and adverse events [1]. The discharge of patients from the intensive care unit (ICU) to a hospital ward is one of the highest-risk transitions of care [1]. This has been attributed to the sickest patients in the hospital being transitioned from a resource-rich environment to one with fewer resources, the number of providers involved, a lack of standardized discharge procedures and the complexity of verbal and written communication between providers and patients and/or their families as well as between providers themselves [2-5].

Opportunities exist to improve the quality of care during ICU discharge, and measures of ICU readmission and hospital mortality following patient discharge from the ICU have been proposed as quality metrics [6-10]. However, the reported incidences of readmission and hospital mortality vary widely, and there are currently no established benchmarks to guide quality improvement efforts [11,12].

Therefore, we performed a secondary meta-analysis of studies by conducting a systematic review of prognostic factors for readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality in patients discharged alive from the ICU to derive literature-based estimates of these outcomes.

Material and methods

We followed the recommendations set forth in the Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statements [13,14]. This study did not require research ethics approval, as all of the data are in the public domain. Similarly, no consent was required from patients, as all of the data were abstracted in aggregate and are available in the public domain.

Search strategy and data sources

We systematically searched the following four databases for articles published between the inception dates of the databases and March 2013: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Searches were completed using a combination of the following terms: “intensive care unit,” “patient discharge” and readmission/mortality/medical emergency team activation, with appropriate wildcards and variations in spelling. We identified additional articles by reviewing the reference lists of studies identified for inclusion.

Inclusion criteria

We selected all studies in which prognostic factors for ICU readmission and hospital mortality were reported. The following were the inclusion criteria: (1) study design was a cohort study, (2) study participants were adult patients (>16 years old) who were discharged alive from the ICU, (3) prognostic factors for ICU discharge were reported and (4) raw data were reported that allowed calculation of the cumulative incidence of ICU readmission or the cumulative incidence of hospital mortality for patients discharged alive from the ICU prior to hospital discharge. Because there is no widely accepted time period for measuring readmission and mortality after patient discharge from the ICU (for example, 24 hours), and because authors of previous reviews have reported the use of different time periods, we included all follow-up periods [15]. We excluded articles that described discharge from a high-dependency or step-down unit. Two reviewers independently and in duplicate reviewed the titles and abstracts of retrieved publications and subsequently the full text of relevant articles. Agreement between reviewers for inclusion of full-text articles was good (κ = 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.67 to 1.00).

Data abstraction

Two reviewers independently and in duplicate abstracted data describing study purpose, design, setting (country, type of ICU), sample size, study population (age, length of follow-up, severity of illness), outcomes (readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality following patient discharge alive from the ICU) and study quality. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. Authors of the included studies were contacted to gather missing data.

Risk of bias assessment

Study quality was evaluated using 11 characteristics: ethical approval reported, eligibility criteria described, definition of cohort timing provided, demographics described, comorbidities reported, severity of illness score reported, study duration reported, completeness of follow-up, adjustment for potential confounders, sample size calculation reported and study limitations reported. Studies that satisfied six or more of the criteria were classified as being of high quality.

Analysis

In the primary analysis, we focused on describing the cumulative incidence of readmission to the ICU and the cumulative incidence of hospital mortality for patients discharged alive from the ICU. Readmissions to the ICU and hospital mortality were calculated using data from each article on raw events (total number of events) and study population (total number of patients discharged alive from the ICU). The cumulative incidence was pooled using both Mantel-Haenszel fixed effects (assumes a single common incidence across studies) and DerSimonian and Laird random effects models (does not assume a single common incidence across studies) [16,17].

Statistical heterogeneity was examined by calculating I2-statistics, wherein a P-value <0.05 and an I2-value >50% indicated the presence of heterogeneity among the included studies [18]. Stratified analyses were performed to examine for potential sources of heterogeneity between studies using prespecified subgroups that included geographic region (North America, Europe, Australasia, other region), ICU type (medical-surgical, cardiovascular, other ICU), patient characteristics (age <60 years vs. ≥60 years, predicted mortality <10% vs. ≥10% according to illness severity score) and study characteristics (patients with do-not-resuscitate (DNR) goals of care included, adjustment for confounding factors, duration of follow up ≤21 days vs. >21 days, sample size <1,000 patients vs. ≥1,000 patients, number of ICUs 1 vs. >1 and a composite measure of study quality).

All data analysis was conducted using Stata version 11.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

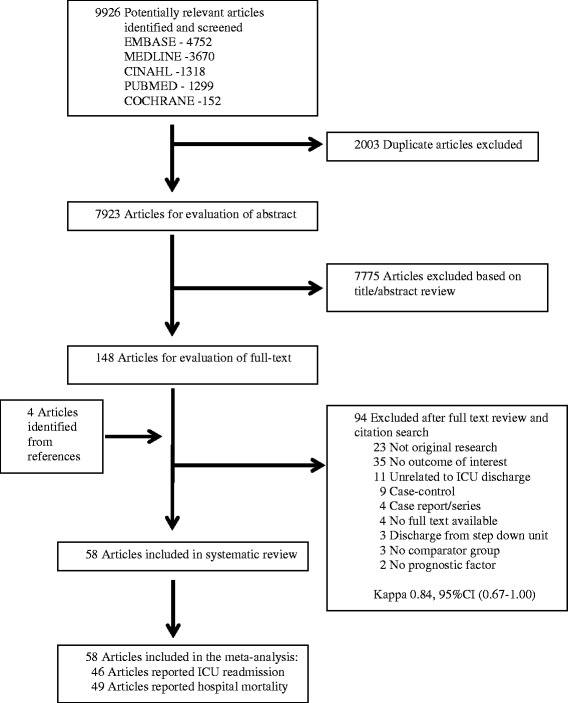

We identified 58 studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria and that had data which allowed calculation of the cumulative incidence of readmission to the ICU (n = 46 studies) or the cumulative incidence of hospital mortality (n = 49 studies) for patients discharged alive from the ICU (Figure 1) [2,4,5,8,11,12,19-70]. The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1. The studies were published between 1986 and 2013 and represented 18 countries, including the United States (n = 12), the United Kingdom (n = 8), Australia (n = 6), Canada (n = 6) and Germany (n = 4). The number of patients within the studies ranged from 86 to 704,963, with an aggregate total of 2,073,170 patients included in our meta-analysis. The majority of studies were conducted in mixed medical-surgical ICUs (n = 34), with fewer studies conducted in cardiac ICUs (n = 7) or exclusively medical ICUs (n = 4) or surgical ICUs (n = 3). The mean (standard deviation) age of patients was 59.7 (5.4) years among the 44 studies in which a mean age was reported. Patient illness severity in most studies was reported based on the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score (n = 31) or the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (n = 12). The majority of studies were single-centered (n = 32), included patients with DNR orders (n = 42) and used multivariable adjustment (n = 49) in their data analysis. Most studies followed patients until hospital discharge (n = 46). In three studies, the investigators reported readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality at fixed time periods following patient discharge from the ICU (48 hours [26], 7 days [44] and 2 weeks [36]).

Figure 1.

Selection process for articles for review. CI, Confidence interval; ICU, Intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Description of included studies a

| Study | Year | Countries | Follow-up | Type of ICU | ICUs, n | Patients, n | Age, yr (mean) | Female (%) | SOI measure | SOI score (mean) | Readmission (%) | Mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strauss et al. [70] | 1986 | USA | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 912 | 50 | N/A | APS | N/A | 15 | 9.9 |

| Rubins et al. [69] | 1988 | USA | Hospital discharge | Medical | 1 | 229 | 59.9 | 2.2 | APACHE II | 10.6 | 13.1 | 3 |

| Chen et al. [68] | 1998 | Canada | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 7 | 5,127 | 59.3 | 38.0 | APACHE II | 17.1 | 4.6 | 5.5 |

| Cohn et al. [67] | 1999 | USA | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 38 | 2,228 | 65.3 | 32.4 | N/A | N/A | 5.7 | 1.0 |

| Cooper et al. [8] | 1999 | USA | Hospital discharge | Variousc | 28 | 103,968 | 63.5 | 48.0 | APACHE III | 44.3 | 6.1 | N/A |

| Smith et al. [66] | 1999 | UK | N/A | Medical-surgical | 1 | 283 | 66 | 45.6 | APACHE II | 17b | 7.8 | 11 |

| Goldfrad and Rowan [65] | 2000 | UK | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 62 | 12,748 | 58.2 | N/A | APACHE II | 14.7 | 8.3 | 17.1 |

| Daly et al. [64] | 2001 | UK | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 5,475 | N/A | 30.5 | APACHE II | 13.7 | 2.6 | 3.7 |

| Rosenberg et al. [5] | 2001 | USA | Hospital discharge | Medical | 1 | 3,310 | 53 | 66.5 | APACHE III | 49 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Moreno et al. [63] | 2001 | Netherlands | Hospital discharge | N/A | 48 | 2,958 | N/A | N/A | SAPS II | 30.1 | N/A | 8.6 |

| Calafiore et al. [61] | 2002 | Italy | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 1 | 1,194 | N/A | 18.5 | N/A | N/A | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| Beck et al. [62] | 2002 | UK | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 1,654 | 57 | 38.3 | APACHE II | 18.3 | 7.6 | 12.6 |

| Kogan et al. [58] | 2003 | Israel | Hospital discharge | N/A | 1 | 1,613 | 63.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.3 | 0.4 |

| Bardell et al. [59] | 2003 | Canada | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 1 | 2,117 | 65 | 30.0 | N/A | N/A | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| Metnitz et al. [57] | 2003 | Austria | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 30 | 15,180 | 62.7 | 39.4 | N/A | N/A | 5.1 | N/A |

| Uusaro et al. [56] | 2003 | Finland | Hospital discharge | N/A | 18 | 20,636 | N/A | N/A | SAPS II | 34 | N/A | 10.1 |

| Azoulay et al. [60] | 2003 | France | Hospital discharge | Variousd | 7 | 1,385 | 65b | 36.5 | SAPS II | 36b | N/A | 10.8 |

| Yoon et al. [53] | 2004 | Korea | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 34 | 1,929 | 55.5 | 35.8 | APACHE III | N/A | 4.1 | 17.3 |

| Duke et al. [55] | 2004 | Australia | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 1,870 | 62b | N/A | APACHE II | 18.5 | 5.1 | 4.9 |

| Fortis et al. [54] | 2004 | Greece | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 86 | 63 | 43.0 | APACHE II | 14 | N/A | 15.1 |

| Vohra et al. [52] | 2005 | UK | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 1 | 7,177 | 70.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.5 | N/A |

| Azoulay et al. [2] | 2005 | Europe, Canada, Israel | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 28 | 1,872 | 60b | 37.4 | SAPS II | 35b | N/A | 10.4 |

| Alban et al. [51] | 2006 | USA | Hospital discharge | Surgical | 1 | 10,840 | 58.8 | N/A | APACHE II | 15.4 | 2.7 | 9.4 |

| Mayr et al. [49] | 2006 | Austria | 1 yr | Medical-surgical | 1 | 3,347 | 59.2 | 28.6 | SAPS II | 37.6 | 3 | 4.3 |

| Priestap and Martin [48] | 2006 | Canada | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 31 | 47,163 | 61.7 | 40.8 | APACHE II | 15.1 | 5.3 | 9.3 |

| Tobin and Santamaria [47] | 2006 | Australia | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 10,963 | 64 | 35.0 | APACHE II | 13b | N/A | 4.4 |

| Fernandez et al. [50] | 2006 | Spain | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 1,159 | 60.2 | N/A | APACHE II | 20b | N/A | 9.6 |

| Medical-surgical | ||||||||||||

| Pilcher et al. [46] | 2007 | Australia/New Zealand | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 41 | 76,690 | 59 | N/A | APACHE III | 46.3 | 5.3 | 5.8 |

| Song et al. [45] | 2007 | Korea | 54.4 mo | N/A | 1 | 1,087 | 65 | N/A | APACHE III | N/A | 8.6 | N/A |

| Ho et al. [42] | 2008 | Australia | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 603 | 53 | N/A | APACHE II | 15.7 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Gajic et al. [44] | 2008 | USA, Netherlands | 7 days | Medical | 1 | 1,242 | N/A | 45.8 | APACHE III | 59.2 | 8.1 | 0.4 |

| Campbell et al. [12] | 2008 | UK | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 4,376 | 63b | 41.1 | APACHE II | 19b | 8.8 | 11.2 |

| Hanane et al. [43] | 2008 | USA | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 3 | 11,659 | 62.7 | 46.8 | APACHE III | 51.3 | 9.1 | 4.5 |

| Kaben et al. [41] | 2008 | Germany | Hospital discharge | Surgical | 1 | 2,852 | 62 | 35.9 | SAPS I | 33.5 | 13.3 | 4.8 |

| Laupland et al. [40] | 2008 | Canada | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 4 | 17,864 | 63.7b | 26.6 | APACHE II | 25.1 | N/A | 6.7 |

| Sakr et al. [39] | 2008 | Europe | 60 days | N/A | 198 | 1,729 | 59.8 | 39.3 | SAPS II | 31.4 | N/A | 7.2 |

| Chrusch et al. [38] | 2009 | Canada | 7 days | Medical, Surgical | 2 | 8,222 | 59.3 | N/A | APACHE II | 18.6 | 5.2 | 0.3 |

| Litmathe et al. [37] | 2009 | Germany | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 1 | 3,374 | 74.3 | 30.3 | N/A | N/A | 5.9 | 2.1 |

| Fernandez et al. [35] | 2010 | Spain | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 31 | 3587 | 61.5 | 33.6 | N/A | N/A | 4.6 | 5.9 |

| Al-Subaie et al. [36] | 2010 | UK | 14 days | Medical-surgical | 1 | 1,185 | 60 | 45.1 | APACHE II | 16b | 7 | 2.9 |

| Utzolino et al. [33] | 2010 | Germany | Hospital discharge | Surgical | 1 | 2,114 | 62.1 | 36.4 | N/A | N/A | 11.8 | 3.7 |

| Silvestre et al. [34] | 2010 | Portugal | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 156 | 55 | 40.4 | APACHE II | 14.6 | N/A | 18.6 |

| Medical-surgical | ||||||||||||

| Renton et al. [29] | 2011 | Australia | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 97 | 247,103 | 59.9 | N/A | APACHE III | 47 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Fernandez et al. [32] | 2011 | Spain | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 31 | 201 | 60.5 | 31 | N/A | N/A | 6 | 22 |

| Kramer et al. [11] | 2011 | USA | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 38 | 229,961 | N/A | 44.0 | N/A | N/A | 6 | N/A |

| Silva et al. [28] | 2011 | Brazil | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 4 | 600 | 60.7 | 43.3 | SAPS II | 25.5 | 9.1 | N/A |

| Laupland et al. [31] | 2011 | France | Hospital discharge | Mixed | N/A | 5992 | 62b | 39 | SAPS II | 40b | N/A | 5.9 |

| Ouanes et al. [30] | 2012 | France | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 4 | 3,462 | 60.6 | 38.3 | SAPS II | 35.1 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| Badawi and Breslow [26] | 2012 | USA | 48 hr/Hospital discharge | Mixed | 402 | 704,963 | 62.1 | 45.9 | APACHE IV | 47 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Reini et al. [21] | 2012 | Sweden | 30 days | Medical-surgical | 1 | 354 | 60.6 | 25.4 | SAPS III | 61b | 3.7 | 8.2 |

| Araújo et al. [27] | 2012 | Portugal | Hospital discharge | Medical-surgical | 1 | 296 | 64.7 | 43.0 | SAPS II | 43.7 | 4.7 | 22.6 |

| Brown et al. [25] | 2012 | USA | 21 days | Medical-surgical | 156 | 196,250 | N/A | N/A | MPMO-III | 10.9 | 5.4 | N/A |

| Joskowiak et al. [24] | 2012 | Germany | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 1 | 7,105 | 69.1 | 30.7 | euroSCORE | 9 | 7.8 | 1.2 |

| Timmers et al. [20] | 2012 | Netherlands | 11 yr | Medical-surgical | 1 | 1,682 | 58.6 | 33.3 | APACHE II | 11.1 | 8 | N/A |

| Mahesh et al. [23] | 2012 | UK | Hospital discharge | Cardiovascular | 1 | 6,101 | N/A | 27.8 | euroSCORE | 7.6 | N/A | 0.39 |

| Ranzani et al. [22] | 2012 | Brazil | Hospital discharge | Medical | 1 | 409 | 48.6 | 49 | APACHE II | 16 | 17.4 | 18.3 |

| Kramer et al. [4] | 2013 | USA | Hospital discharge | Mixed | 105 | 263,082 | 61.5 | N/A | APACHE IV | 41.3 | 6.3 | N/A |

| Yip and Ho [19] | 2013 | Australia | 34 mo | Medical-surgical | 1 | 1,446 | 50.2 | 35.7 | APACHE II | 19b | 7.3 | 12.3 |

aAPACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; APS, Acute Physiology Score; ICU, Intensive care unit; MICU, Medical intensive care unit; MPMO-III, Mortality Probability Admission Model; N/A, Not available; NICU, Neurosurgical intensive care unit; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SICU, Surgical intensive care unit;. bMedian score. cMixed, MICU, SICU, NICU. dTwo Mixed, two SICUs and three MICUs.

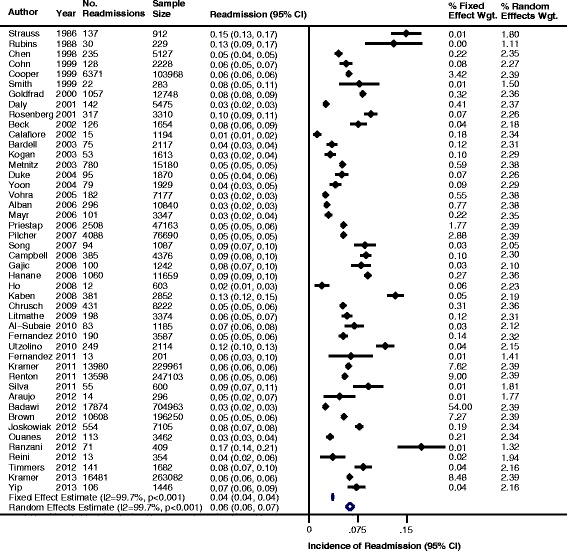

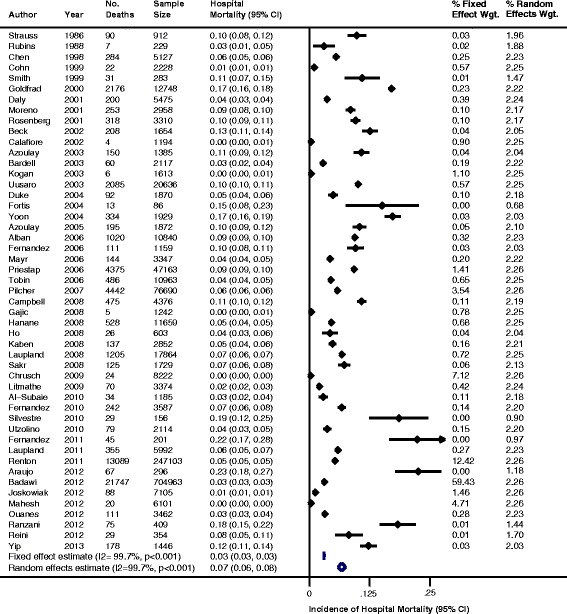

The pooled cumulative incidence of readmission to the ICU and cumulative incidence of hospital mortality using both fixed effects models and random effects models are summarized in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively. In patients discharged alive from the ICU, the fixed effects pooled cumulative incidence of readmission to the ICU during the same hospitalization was 4.0 readmissions per 100 patient discharges (95% CI, 3.9 to 4.0), whereas the random effects pooled cumulative incidence was 6.3 readmissions per 100 patients (95% CI, 5.6 to 6.9). In patients discharged alive from the ICU, the fixed effects pooled hospital mortality cumulative incidence during the same hospitalization was 3.3 deaths per 100 patient discharges (95% CI, 3.3 to 3.3), whereas the random effects pooled cumulative incidence was 6.8 deaths per 100 patient discharges (95% CI, 6.1 to 7.6). Heterogeneity among these estimates was high, with I2-values of 99.7% and P < 0.001 for all estimates.

Figure 2.

Incidence of readmission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for patients discharged alive from the ICU. CI, Confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Incidence of hospital mortality for patients discharged alive from the intensive care unit. CI, Confidence interval.

The stratified pooled cumulative incidence of readmission to the ICU and the stratified pooled cumulative incidence of hospital mortality for patients discharged alive from the ICU varied by geographic region, ICU type, patient characteristics and study characteristics (Table 2). Compared to medical-surgical ICUs, lower cumulative incidences of readmission (3.8 vs. 5.6 readmissions per 100 patient discharges) and hospital mortality (0.1 vs. 4.4 deaths per 100 patient discharges) were reported for cardiovascular ICUs. The cumulative incidence of ICU readmission and hospital mortality varied according to age, severity of illness and goals of care designations of the patients included in the studies. For example, studies that excluded patients with DNRs had lower cumulative incidences of readmission (3.5 vs. 5.5 readmissions per 100 patient discharges) and hospital mortality (2.2 vs. 3.5 deaths per 100 patient discharges) compared to studies that included DNR patients.

Table 2.

Pooled cumulative incidence of ICU readmission and hospital mortality after patient discharge from ICU a

| Variables | ICU readmission | Hospital mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n | Patients, n | Fixed effects pooled proportion (95% CI) | Random effects pooled proportion (95% CI) | Studies, n | Patients, n | Fixed effects pooled proportion (95% CI) | Random effects pooled proportion (95% CI) | |

| Total pooled estimates | 46 | 2,002,269 | 0.040 (0.039 - 0.040) | 0.063 (0.056 - 0.069) | 49 | 1,254,183 | 0.033 (0.033 - 0.033) | 0.068 (0.061 - 0.076) |

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| North America | 16 | 1,591,273 | 0.037 (0.037 - 0.038) | 0.064 (0.053 - 0.076) | 13 | 815,876 | 0.030 (0.029 - 0.030) | 0.050 (0.036 - 0.065) |

| Europe | 20 | 77,646 | 0.048 (0.047 - 0.049) | 0.062 (0.050 - 0.074) | 27 | 95,681 | 0.025 (0.024 - 0.026) | 0.081 (0.064 - 0.098) |

| Australia / New Zealand | 5 | 327,712 | 0.054 (0.054 - 0.055) | 0.051 (0.047 - 0.056) | 6 | 338,675 | 0.054 (0.053 - 0.055) | 0.057 (0.051 - 0.063) |

| Other regions | 5 | 5,638 | 0.049 (0.043 - 0.054) | 0.081 (0.050 - 0.111) | 3 | 3,951 | 0.010 (0.007 - 0.013) | 0.119 (0.000 - 0.256) |

| ICU type | ||||||||

| Medical-surgical ICU | 28 | 883,365 | 0.056 (0.055-0.056) | 0.058 (0.054 - 0.061) | 29 | 471,305 | 0.044 (0.044 - 0.045) | 0.086 (0.073 - 0.099) |

| Cardiovascular ICU | 6 | 23,195 | 0.038 (0.035-0.040) | 0.044 (0.024 - 0.065) | 6 | 22,119 | 0.007 (0.006 - 0.008) | 0.012 (0.006 - 0.019) |

| Other ICU types | 12 | 1,095,709 | 0.032 (0.032-0.033) | 0.081 (0.065 - 0.096) | 14 | 760,759 | 0.031 (0.031 - 0.032) | 0.066 (0.049 - 0.082) |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||||

| Age <60 | 16 | 376,251 | 0.054 (0.053 - 0.054) | 0.065 (0.057 - 0.072) | 18 | 378,326 | 0.041 (0.041 - 0.042) | 0.092 (0.075 - 0.109) |

| Age >60 | 29 | 1,624,824 | 0.038 (0.037 - 0.038) | 0.062 (0.053 - 0.070) | 28 | 865,604 | 0.033 (0.032 - 0.033) | 0.060 (0.049 - 0.070) |

| SOI predicted <10% mortality | 3 | 3,369 | 0.086 (0.077 - 0.095) | 0.086 (0.077 - 0.095) | 2 | 9,059 | 0.005 (0.003 - 0.006) | 0.044 (0.000 - 0.125) |

| SOI predicted >10% mortality | 31 | 1,534,181 | 0.036 (0.036 - 0.037) | 0.064 (0.056 - 0.072) | 39 | 1,228,973 | 0.035 (0.035 - 0.036) | 0.076 (0.067 - 0.084) |

| Study characteristics | ||||||||

| DNR patients excluded | 13 | 1,372,056 | 0.035 (0.035 - 0.035) | 0.068 (0.056 - 0.080) | 14 | 1,132,425 | 0.022 (0.021 - 0.023) | 0.057 (0.045 - 0.070) |

| DNR patients included | 33 | 630,213 | 0.055 (0.055 - 0.056) | 0.059 (0.054 - 0.064) | 35 | 121,758 | 0.035 (0.035 - 0.035) | 0.076 (0.064 - 0.089) |

| High study quality | 36 | 1,643,624 | 0.037 (0.037 -0.037) | 0.066 (0.058 - 0.073) | 40 | 1,215,780 | 0.033 (0.033 - 0.033) | 0.071 (0.063 - 0.079) |

| Low study quality | 10 | 358,645 | 0.058 (0.057-0.059) | 0.052 (0.043 - 0.061) | 9 | 38,403 | 0.034 (0.032 - 0.036) | 0.062 (0.033 - 0.091) |

| Adjusted for confounding factors | 41 | 1,618,703 | 0.037 (0.036 - 0.037) | 0.060 (0.054 - 0.067) | 43 | 1,231,324 | 0.034 (0.034 - 0.035) | 0.065 (0.057 - 0.072) |

| Not adjusted for confounding factors | 5 | 383,566 | 0.063 (0.062 - 0.064) | 0.076 (0.069 - 0.082) | 6 | 22,859 | 0.013 (0.011 - 0.014) | 0.110 (0.034 – 0.186) |

| Follow-up >21 days | 41 | 1,090,407 | 0.057 (0.057 - 0.058) | 0.061 (0.057 - 0.065) | 45 | 538,571 | 0.045 (0.044 - 0.045) | 0.076 (0.066 - 0.086) |

| Follow-up <21 days | 5 | 911,862 | 0.029 (0.029 - 0.029) | 0.056 (0.037 - 0.074) | 4 | 715,612 | 0.028 (0.027 - 0.028) | 0.016 (0.000 - 0.036) |

| Patient number >1000 | 37 | 1,998,382 | 0.040 (0.039 - 0.040) | 0.060 (0.053 - 0.067) | 39 | 1,250,654 | 0.033 (0.033 - 0.033) | 0.060 (0.052 - 0.068) |

| Patient number <1000 | 9 | 3,887 | 0.058 (0.051 - 0.065) | 0.086 (0.046 - 0.126) | 10 | 3,529 | 0.085 (0.076 - 0.094) | 0.129 (0.089 - 0.168) |

| Multiple ICU study | 19 | 1,934,123 | 0.040 (0.039 - 0.040) | 0.051 (0.035 - 0.066) | 20 | 1,177,518 | 0.035 (0.035 – 0.036) | 0.076 (0.064 - 0.087) |

| Single ICU study | 27 | 68,146 | 0.041 (0.040 - 0.043) | 0.063 (0.059 - 0.067) | 29 | 76,665 | 0.017 (0.016 - 0.018) | 0.064 (0.053 - 0.075) |

aCI, Confidence interval; DNR, Do-not-resuscitate order; ICU, Intensive care unit; SOI, Severity of illness.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we report the first pooled estimates of readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality for patients discharged alive from the ICU. These estimates suggest that, on average, for every 100 patients discharged alive from the ICU, between 4 and 6 patients will be readmitted to the ICU and between 3 and 7 patients will die prior to hospital discharge. Important variations in the incidence of readmission and mortality were observed according to geographic regions and patient-related, institutional and study methodological characteristics.

Our study underscores important opportunities and challenges in improving the quality of care provided to patients discharged from intensive care. We identified estimates of readmission and death for patients discharged alive from the ICU that are similar in magnitude to the estimates of adverse events reported in an Institute of Medicine report, To Err Is Human, that prompted major efforts to improve the safety and quality of care [71,72]. Although readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality after ICU discharge do not equate to medical errors or adverse events and are not necessarily preventable [12], our data highlight that patient discharge from the ICU is a high-risk transition of care. There are opportunities to reduce the risks pertaining to patients (for example, relapsing and/or remitting comorbid illness), providers (for example, differential continuity of care), institutions (for example, availability of transition resources) and health systems (for example, ICU capacity) [73]. Our analysis reinforces the importance of measuring performance and considering internal (that is, monitoring performance over time) and external (that is, monitoring performance across institutions) benchmarking to guide quality improvement activities. For example, deviations from anticipated performance could be used to trigger audits of patient care to identify potentially preventable events and their root causes and thereby implement locally tailored interventions.

Our results can be used to inform quality metrics designed to measure the incidence of readmission to the ICU and the incidence of hospital mortality after patient discharge from the ICU. Currently, there is no consensus on ICU benchmarks for readmission and post-ICU mortality. ICU readmission was initially identified by Cooper et al. as an important indicator that captured complementary aspects of hospital-related performance [8]. Rosenberg et al. identified a readmission incidence of 7% and suggested its use as a quality-of-care indicator [5]. More recently, professional societies [6], provider groups [74] and accreditation organizations [75] across multiple countries [76] have proposed ICU readmission as a quality indicator, but they have not specified benchmark values. Measures of ICU and hospital mortality have similarly been proposed [10,76]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been used to derive quality improvement benchmarks [77], and our present study provides literature-based estimates of readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality that could be used by institutions to select potential benchmark values.

So, which literature-based estimates should be considered? Our analyses provide two sets of pooled estimates for both ICU readmission and hospital mortality that offer a range of potential benchmarks. The fixed effects model assumes that ICU readmission incidence is the same from study to study and provides a weighted average that gives large studies greater weight [78]. The random effects model does not assume that the ICU readmission incidence is the same from study to study (that is, that it may vary from study to study) and provides a weighted average that gives studies of different sizes similar weights [79]. Although the random effects model does better justice to the full range of data available, it does potentially allow a larger weight to be given to smaller studies that may have been selected for publication on the basis of their higher event rates [18]. Therefore, one approach would be to consider ICU readmission incidence (6 patients per 100 patient discharges) and hospital mortality incidence (7 patients per 100 patient discharges) above the random effects estimates to represent suboptimal quality of care. To represent adequate quality of care accurately, it may be necessary to consider ICU readmission incidence (4 to 6 patients per 100 patient discharges) and hospital mortality incidence (3 to 7 patients per 100 patient discharges) using both the fixed effects and random effects models. It may also be necessary to consider ICU readmission incidence (4 patients per 100 patient discharges) and hospital mortality incidence (3 patients per 100 patient discharges) below the fixed effects estimates as high-quality care and benchmark targets. The stratified analyses can be used to further refine benchmark selection to more closely represent different organizations’ patient and institutional characteristics. As an important caveat, the data highlight the complexity of identifying appropriate benchmarks, reinforce the importance of a cautious approach to adopting benchmarks and suggest potential value in employing benchmark ranges as opposed to individual values in quality improvement initiatives.

Our data also highlight that hospital mortality is common among patients discharged from the ICU. This reinforces observations that the utilization of intensive care resources by patients with life-limiting illnesses is steadily rising and that end-of-life care is increasingly initiated in the ICU [80,81]. Whereas many of these patients will die during their ICU stay, others will be discharged from the ICU before dying. This suggests that consideration needs to be given to ensure that end-of-life care is effectively delivered during transitions of care. Incorporating joint metrics for goals of care reconciliation at the time of patient discharge from the ICU, as well as both ICU readmission and hospital mortality following patient discharge from the ICU, may help in the evaluation and monitoring of the care provided to patients discharged from the ICU who are at the end of life [82].

There are caveats to our study findings. First, the studies included in this analysis were identified by conducting a literature search targeted for studies in which associations between prognostic factors and the risk of readmission to ICU and hospital mortality for patients discharged alive from the ICU were examined. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the incidence in other studies reporting readmission and death after patient discharge would be different from ours. Second, we identified heterogeneity that is not fully explained. This is an expected finding, given the diversity of geographic locations (for example, health systems, available resources), institutions (for example, procedures for discharge and post-ICU care), providers (for example, discharge practices) and patient populations (for example, severity of illness, patient and family care preferences) in the included studies. We have discussed the relative merits and limitations of using fixed effects models and random effects models to interpret benchmarks. Against this backdrop of heterogeneity, our meta-analysis summarizes what other institutions are reporting. Third, in the majority of studies, patients were followed to hospital discharge and data at fixed time periods following patient discharge from the ICU were not reported. Although measuring readmission to the ICU and hospital mortality during the remainder of a patient’s hospital stay provides valuable information, the implications of these events likely vary by time period (that is, implication of patient readmission within 24 hours is likely different from readmission within 7 days [15]) and may introduce bias into external benchmarking activities if the hospitals being compared employ different discharge practices (for example, timing of discharge or disposition to home, to rehabilitation, to long-term care [83]). Establishing consensus time periods for measuring quality metrics of transitions of patient care between the ICU and hospital ward would facilitate future research and quality improvement initiatives.

Conclusions

On the basis of our analysis of the literature, for every 100 patients discharged alive from the ICU, on average, between 4 and 6 patients will be readmitted to the ICU and between 3 and 7 patients will die prior to hospital discharge. Opportunities exist to improve the quality of care provided to patients discharged from intensive care. The literature-based estimates derived from this systematic review and meta-analysis can be used to inform the selection of benchmarks for quality metrics of transitions of patient care between the ICU and the hospital ward.

Key messages

The discharge of patients from the ICU to a hospital ward is a vulnerable period in health care delivery.

Estimates suggest that for every 100 patients discharged alive from the ICU, on average, between 4 and 6 patients will be readmitted to the ICU and between 3 and 7 patients will die prior to hospital discharge.

The literature-based estimates derived from this systematic review and meta-analysis can be used to inform the selection of benchmarks for quality metrics of transitions of patient care between the ICU and the hospital ward.

Acknowledgements

The project was supported by an Establishment Grant (20100368) from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. WAG and HTS are supported by Population Health Investigator Awards from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. HTS is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. DR is supported by an Alberta – Innovates Health Solutions Clinician Fellowship Award, a Knowledge Translation Canada Strategic Training in Health Research Fellowship and funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of this study. FSH, DR and HTS had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We would like to thank Simon Berthelot for aiding with the literature search and reviewing abstracts and Nik Bobrovitz for aiding in the selection and critical appraisal of publications.

Abbreviations

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- APS

Acute Physiology Score

- CI

Confidence interval

- DNR

Do not resuscitate

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- MICU

Medical intensive care unit

- MPMO-III

Mortality Probability Admission Model

- NICU

Neurosurgical intensive care unit

- SAPS

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- SICU

Surgical intensive care unit

- SOI

Severity of illness

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All six authors contributed to the study’s conception, design and interpretation. FSH was responsible for searching the literature, reviewing the abstracts and selecting publications and critically appraising them. FSH, DR and HTS performed the analyses. FSH, DR, TCT, DZ, WAG and HTS assisted in the successive revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

F Shaun Hosein, Email: fshosein@ucalgary.ca.

Derek J Roberts, Email: derek.roberts01@gmail.com.

Tanvir Chowdhury Turin, Email: turin.chowdhury@ucalgary.ca.

David Zygun, Email: zygun@ualberta.ca.

William A Ghali, Email: wghali@ucalgary.ca.

Henry T Stelfox, Email: tstelfox@ucalgary.ca.

References

- 1.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323. doi: 10.1002/jhm.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay É, Alberti C, Legendre I, Buisson CB, Le Gall JR, European Sepsis Group Post-ICU mortality in critically ill infected patients: an international study. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosein FS, Bobrovitz N, Berthelot S, Zygun D, Ghali WA, Stelfox HT. A systematic review of tools for predicting severe adverse events following patient discharge from intensive care units. Crit Care. 2013;17:R102. doi: 10.1186/cc12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer AA, Higgins TL, Zimmerman JE. The association between ICU readmission rate and patient outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:24–33. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182657b8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg AL, Hofer TP, Hayward RA, Strachan C, Watts CM. Who bounces back? Physiologic and other predictors of intensive care unit readmission. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:511–518. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes A, Moreno RP, Azoulay É, Capuzzo M, Chiche JD, Eddleston J, Endacott R, Ferdinande P, Flaatten H, Guidet B, Kuhlen R, León-Gil C, Martin Delgado MC, Metnitz PG, Soares M, Sprung CL, Timsit JF, Valentin A. Prospectively defined indicators to improve the safety and quality of care for critically ill patients: a report from the Task Force on Safety and Quality of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Thoracic So Fair allocation of intensive care unit resources. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1282–1301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.ats7-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper GS, Sirio CA, Rotondi AJ, Shepardson LB, Rosenthal GE. Are readmissions to the intensive care unit a useful measure of hospital performance? Med Care. 1999;37:399–408. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valentin A, Ferdinande P, ESICM Working Group on Quality Improvement Recommendations on basic requirements for intensive care units: structural and organizational aspects. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1575–1587. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pronovost PJ, Miller MR, Dorman T, Berenholtz SM, Rubin H. Developing and implementing measures of quality of care in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:297–303. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200108000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer AA, Higgins TL, Zimmerman JE. Intensive care unit readmissions in U.S. hospitals: patient characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2011;40:3–10. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822d751e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell AJ, Cook JA, Adey G, Cuthbertson BH. Predicting death and readmission after intensive care discharge. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:656–662. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB, for the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott M, Worrall-Carter L, Page K. Intensive care readmission: a contemporary review of the literature. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30:121–137. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson SG. Why and how sources of heterogeneity should be investigated. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. 2. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yip B, Ho K. Eosinopenia as a predictor of unexpected re-admission and mortality after intensive care unit discharge. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013;41:231–241. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1304100130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmers TK, Verhofstad MHJ, Moons KGM, Leenen LPH. Patients’ characteristics associated with readmission to a surgical intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:e120–e128. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reini K, Fredrikson M, Oscarsson A. The prognostic value of the Modified Early Warning Score in critically ill patients: a prospective, observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29:152–157. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835032d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranzani OT, Prada LF, Zampieri FG, Battaini LC, Pinaffi JV, Setogute YC, Salluh JI, Povoa P, Forte DN, Azevedo LC, Park M. Failure to reduce C-reactive protein levels more than 25% in the last 24 hours before intensive care unit discharge predicts higher in-hospital mortality: a cohort study. J Crit Care. 2012;27:525. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joskowiak D, Wilbring M, Szlapka M, Georgi C, Kappert U, Matschke K, Tugtekin SM. Readmission to the intensive care unit after cardiac surgery: a single-center experience with 7105 patients. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2012;53:671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown SE, Ratcliffe SJ, Kahn JM, Halpern SD. The epidemiology of intensive care unit readmissions in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:955–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1720OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badawi O, Breslow MJ. Readmissions and death after ICU discharge: development and validation of two predictive models. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Araújo I, Gonçalves-Pereira J, Teixeira S, Nazareth R, Silvestre J, Mendes V, Tapadinhas C, Póvoa P. Assessment of risk factors for in-hospital mortality after intensive care unit discharge. Biomarkers. 2012;17:180–185. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.654407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva MC M, de Sousa RM C, Padilha KG. Factors associated with death and readmission into the intensive care unit. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2011;19:911–919. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692011000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renton J, Pilcher DV, Santamaria JD, Stow P, Bailey M, Hart G, Duke G. Factors associated with increased risk of readmission to intensive care in Australia. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1800–1808. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouanes I, Schwebel C, Français A, Bruel C, Philippart F, Vesin A, Soufir L, Adrie C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Misset B, Outcomerea Study Group A model to predict short-term death or readmission after intensive care unit discharge. J Crit Care. 2012;27:422. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laupland KB, Misset B, Souweine B, Tabah A, Azoulay É, Goldgran-Toledano D, Dumenil AS, Vésin A, Jamali S, Kallel H, Clec’h C, Darmon M, Schwebel C, Timsit JF. Mortality associated with timing of admission to and discharge from ICU: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:321. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez R, Tizon AI, Gonzalez J, Monedero P, Garcia-Sanchez M, de la Torre MV, Ibañez P, Frutos F, del Nogal F, Gomez MJ, Marcos A, Hernández G, Sabadell Score Group Intensive care unit discharge to the ward with a tracheostomy cannula as a risk factor for mortality: a prospective, multicenter propensity analysis. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2240–2245. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182227533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Utzolino S, Kaffarnik M, Keck T, Berlet M, Hopt UT. Unplanned discharges from a surgical intensive care unit: readmissions and mortality. J Crit Care. 2010;25:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silvestre J, Coelho L, Póvoa P. Should C-reactive protein concentration at ICU discharge be used as a prognostic marker? BMC Anesthesiol. 2010;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernandez R, Serrano JM, Umaran I, Abizanda R, Carrillo A, Lopez-Pueyo MJ, Rascado P, Balerdi B, Suberviola B, Hernandez G, Sabadell Score Study Group Ward mortality after ICU discharge: a multicenter validation of the Sabadell score. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1196–1201. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Subaie N, Reynolds T, Myers A, Sunderland R, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Hall GM. C-reactive protein as a predictor of outcome after discharge from the intensive care: a prospective observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:318–325. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litmathe J, Kurt M, Feindt P, Gams E, Boeken U. Predictors and outcome of ICU readmission after cardiac surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:391–394. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chrusch CA, Olafson KP, McMillan PM, Roberts DE, Gray PR. High occupancy increases the risk of early death or readmission after transfer from intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2753–2758. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a57b0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakr Y, Vincent J, Ruokonen E, Pizzamiglio M, Installe E, Reinhart K, Moreno R, the Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients Investigators Sepsis and organ system failure are major determinants of post–intensive care unit mortality. J Crit Care. 2008;23:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laupland KB, Shahpori R, Kirkpatrick AW, Stelfox HT. Hospital mortality among adults admitted to and discharged from intensive care on weekends and evenings. J Crit Care. 2008;23:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaben A, Correa F, Reinhart K, Settmacher U, Gummert J, Kalff R, Sakr Y. Readmission to a surgical intensive care unit: incidence, outcome and risk factors. Crit Care. 2008;12:R123. doi: 10.1186/cc7023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho KM, Lee KY, Dobb GJ, Webb SA. C-reactive protein concentration as a predictor of in-hospital mortality after ICU discharge: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:481–487. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanane T, Keegan MT, Seferian EG, Gajic O, Afessa B. The association between nighttime transfer from the intensive care unit and patient outcome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2232–2237. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181809ca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gajic O, Malinchoc M, Comfere TB, Harris MR, Achouiti A, Yilmaz M, Schultz MJ, Hubmayr RD, Afessa B, Farmer JC. The Stability and Workload Index for Transfer score predicts unplanned intensive care unit patient readmission: initial development and validation. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:676–682. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318164E3B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song SW, Lee HS, Kim JH, Kim MS, Lee JM, Zo JI. Readmission to intensive care unit after initial recovery from major thoracic oncology surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1838–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilcher DV, Duke GJ, George C, Bailey MJ, Hart G. After-hours discharge from intensive care increases the risk of readmission and death. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:477–485. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0703500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobin AE, Santamaria JD. After-hours discharges from intensive care are associated with increased mortality. Med J Aust. 2006;184:334–337. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Priestap FA, Martin CM. Impact of intensive care unit discharge time on patient outcome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2946–2951. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000247721.97008.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mayr VD, Dünser MW, Greil V, Jochberger S, Luckner G, Ulmer H, Friesenecker BE, Takala J, Hasibeder WR. Causes of death and determinants of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2006;10:R154. doi: 10.1186/cc5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez R, Baigorri F, Navarro G, Artigas A. A modified McCabe score for stratification of patients after intensive care unit discharge: the Sabadell score. Crit Care. 2006;10:R179. doi: 10.1186/cc5136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alban RF, Nisim AA, Ho J, Nishi GK, Shabot MM. Readmission to surgical intensive care increases severity-adjusted patient mortality. J Trauma. 2006;60:1027–1031. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000218217.42861.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vohra HA, Goldsmith IRA, Rosin MD, Briffa NP, Patel RL. The predictors and outcome of recidivism in cardiac ICUs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoon KB, Koh SO, Han DW, Kang OC. Discharge decision-making by intensivists on readmission to the intensive care unit. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:193–198. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fortis A, Mathas C, Laskou M, Kolias S, Maguina N. Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System-28 as a tool of post ICU outcome prognosis and prevention. Minerva Anestesiol. 2004;70:71–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duke GJ, Green JV, Briedis JH. Night-shift discharge from intensive care unit increases the mortality-risk of ICU survivors. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32:697–701. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uusaro A, Kari A, Ruokonen E. The effects of ICU admission and discharge times on mortality in Finland. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:2144–2148. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Metnitz PGH, Fieux F, Jordan B, Lang T, Moreno R, Gall JR. Critically ill patients readmitted to intensive care units–lessons to learn? Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kogan A, Cohen J, Raanani E, Sahar G, Orlov B, Singer P, Vinde BA. Readmission to the intensive care unit after “fast-track” cardiac surgery: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:503–507. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bardell T, Legare JF, Buth KJ, Hirsch GM, Ali IS. ICU readmission after cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:354–359. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00767-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Azoulay É, Adrie C, De Lassence A, Pochard F, Moreau D, Thiery G, Cheval C, Moine P, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Alberti C, Cohen Y, Timsit JF. Determinants of postintensive care unit mortality: a prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:428–432. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000048622.01013.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calafiore AM, Scipioni G, Teodori G, Di Giammarco G, Di Mauro M, Canosa C, Iacò AL, Vitolla G. Day 0 intensive care unit discharge - risk or benefit for the patient who undergoes myocardial revascularization? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:377–384. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(01)01151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beck DH, McQuillan P, Smith GB. Waiting for the break of dawn? The effects of discharge time, discharge TISS scores and discharge facility on hospital mortality after intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1287–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moreno R, Miranda D, Matos R, Fevereiro T. Mortality after discharge from intensive care: the impact of organ system failure and nursing workload use at discharge. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:999–1004. doi: 10.1007/s001340100966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daly K, Beale R, Chang RW. Reduction in mortality after inappropriate early discharge from intensive care unit: logistic regression triage model. BMJ. 2001;322:1274–1276. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldfrad C, Rowan K. Consequences of discharges from intensive care at night. Lancet. 2000;355:1138–1142. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith L, Orts CM, O’Neil I, Batchelor AM, Gascoigne AD, Baudouin SV. TISS and mortality after discharge from intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1061–1065. doi: 10.1007/s001340051012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohn WE, Sellke FW, Sirois C, Lisbon A, Johnson RG. Surgical ICU recidivism after cardiac operations. Chest. 1999;116:688–692. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen LM, Martin CM, Keenan SP, Sibbald WJ. Patients readmitted to the intensive care unit during the same hospitalization: clinical features and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1834–1841. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rubins HB, Moskowitz MA. Discharge decision-making in a medical intensive care unit: identifying patients at high risk of unexpected death or unit readmission. Am J Med. 1988;84:863–869. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strauss MJ, LoGerfo JP, Yeltatzie JA, Temkin N, Hudson LD. Rationing of intensive care unit services: an everyday occurrence. JAMA. 1986;255:1143–1146. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03370090065021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: What have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293:2384–2390. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Vos M, Graafmans W, Keesman E, Westert G, van der Voort PH. Quality measurement at intensive care units: Which indicators should we use? J Crit Care. 2007;22:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) ACHS Clinical Indicator Users’ Manual 2012. Ultimo, NSW, Australia: ACHS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flaatten H. The present use of quality indicators in the intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:1078–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Januel JM, Chen G, Ruffieux C, Quan H, Douketis JD, Crowther MA, Colin C, Ghali WA, Burnand B, IMECCHI Group Symptomatic in-hospital deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism following hip and knee arthroplasty among patients receiving recommended prophylaxis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307:294–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thompson SG. Meta-analysis of clinical trials. In: Armitage P, Colton E, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. 2. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berkey CS, Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Colditz GA. A random-effects regression model for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1995;14:395–411. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pisani MA. Considerations in caring for the critically ill older patient. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:83–95. doi: 10.1177/0885066608329942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, Rubenfeld GD, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-Of-Life Peer Group Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin J. Clinicians examine advances and challenges in improving quality of end-of-life care in the ICU. JAMA. 2013;310:2493–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reineck LA, Pike F, Le TQ, Cicero BD, Iwashyna TJ, Kahn JM. Hospital factors associated with discharge bias in ICU performance measurement. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1055–1064. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]