Abstract

Objective

To explore any differences in efficacy and safety outcomes between European (EU) (n = 684) and North American (NA) (n = 395) patients in the AFFIRM trial (NCT00974311).

Patients and Methods

Phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational AFFIRM trial in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) after docetaxel. Participants were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive oral enzalutamide 160 mg/day or placebo. The primary end point was overall survival (OS) in a post hoc analysis.

Results

Enzalutamide significantly improved OS compared with placebo in both EU and NA patients. The median OS in EU patients was longer than NA patients in both treatment groups. However, the relative treatment effect, expressed as hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval, was similar in both regions: 0.64 (0.50, 0.82) for EU and 0.63 (0.47, 0.83) for NA. Significant improvements in other end points further confirmed the benefit of enzalutamide over placebo in patients from both regions. The tolerability profile of enzalutamide was comparable between EU and NA patients, with fatigue and nausea the most common adverse events. Four EU patients (4/461 enzalutamide-treated, 0.87%) and one NA patient (1/263 enzalutamide-treated, 0.38%) had seizures. The difference in median OS was related in part to the timing of development of mCRPC and baseline demographics on study entry.

Conclusion

This post hoc exploratory analysis of the AFFIRM trial showed a consistent OS benefit for enzalutamide in men with mCRPC who had previously progressed on docetaxel in both NA- and EU-treated patients, although the median OS was higher in EU relative to NA patients. Efficacy benefits were consistent across end points, with a comparable safety profile in both regions.

Keywords: androgen receptor inhibitor, enzalutamide, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

Introduction

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), characterised by disease progression after surgical or medical castration, remains a chronic disease with a poor prognosis 1. In vitro, in vivo and profiling studies of human prostate cancers show that continued activation of signalling through the androgen receptor (AR) pathway is frequent and that the disease remains sensitive to further hormonal treatments 2–4. Several new agents have shown improvements in overall survival (OS) in patients with mCRPC previously treated with docetaxel 5; one is the AR inhibitor enzalutamide (formerly MDV3100). This once-daily, oral hormonal treatment does not require co-administration of prednisone and can be taken with or without food 6. The drug inhibits multiple steps in the AR signalling pathway, including binding of testosterone to the AR, translocation of the hormone/receptor complex to the nucleus and binding of the ligand/receptor complex to DNA, inhibiting transcription 7,8.

The approval for use of enzalutamide for patients with mCRPC previously treated with docetaxel is based on the results of the randomised, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational AFFIRM trial (NCT00974311), with a primary end point of OS 6. In that trial, enzalutamide showed a significant benefit over placebo in OS (median OS was 18.4 months in the enzalutamide group vs 13.6 months in the placebo group; hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; P < 0.001). The superiority of enzalutamide over placebo was consistent for all secondary end points, including PSA response, objective soft tissue response, health-related quality of life (HRQL), time to PSA progression, radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) and time to first skeletal-related event (SRE) (all P < 0.001 vs placebo) 6.

Most patients (90%) in the AFFIRM trial were recruited from Europe (EU) and North America (NA). However, clinical management, diagnosis and treatment guidelines for prostate cancer differ between these regions. For example, detection and screening practices in NA are more aggressive than in EU, which may explain, in part, why the NA patients are diagnosed with prostate cancer younger and have lower PSA levels than EU patients 9. Treatment patterns also differ, as do the treatment guidelines in use in each region 10–15, to which general adherence and interpretation may also vary broadly. How they are used in practice is also influenced by the experience and preference of the treating centre and physician 16,17. Variations in the availability of new treatments, and the time of use in practice, also exist, as does the use of second-line chemotherapy after docetaxel and bisphosphonates 18–23. All of these factors, alone or together, may explain differences in disease recurrence and progression patterns. This post hoc exploratory analysis of the AFFIRM trial was undertaken to explore the outcomes of EU and NA patients enrolled in the study. The study was not powered or designed to assess regional differences at baseline; nevertheless, such differences may exist and affect outcomes.

Patients and Methods

The AFFIRM study design and methods have previously been published 6. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer, castrate levels of testosterone (<50 ng/dL, 1.7 nmol/L), previous treatment with docetaxel and progressive disease (defined by PSA, soft tissue disease or bone disease progression) were enrolled in the AFFIRM trial from September 2009 to November 2010. Patients were randomly assigned to study treatment (2:1, enzalutamide 160 mg/day:placebo) after stratification according to baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score (0 or 1 vs 2) and the average of daily pain scores over the 7 days before randomisation using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) question 3 (<4 vs ≥4) 6.

In the present post hoc subanalysis, the primary and secondary end points were evaluated in the patient subgroups from both EU and NA regions and the relative treatment effect (enzalutamide vs placebo) compared. The primary end point was OS. Subgroup analyses of OS were conducted to determine whether treatment effects were consistent across patient subgroups including age, baseline characteristics and previous treatment. The variable list in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model included study arm, baseline ECOG PS group (0–1 vs 2), baseline BPI-SF group (0–3 vs 4–10), type of progression at baseline (PSA only vs radiographic), visceral disease at baseline (‘Yes’ vs ‘No’), baseline haemoglobin (g/L), baseline lactate dehydrogenase (U/L), geographic region (EU vs NA) and study arm-by-geographic region interaction term. The significance of geographic region and interaction term was assessed using the chi-squared test for the corresponding HR term in the full model (region and interaction term assessed simultaneously with all listed variables). Secondary end points included measures of response (PSA level, objective soft tissue response and HRQL assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate [FACT-P] questionnaire) and measures of disease progression (time to PSA progression, rPFS and time to first SRE). Evaluation of pain progression was included as an exploratory end point (as an increase from baseline in the FACT-P pain scale). The definitions of the end points used in this exploratory analysis and the statistical methods used are provided in the Online Supplementary Information in Table S1. Information on prostate cancer treatments that patients in the two regions received after discontinuation of enzalutamide was also recorded. Data obtained by 25 September 2011 were included in the analysis.

Results

This analysis included 684 EU patients and 395 NA patients. Overall, the patient baseline characteristics were similar between the two regions (Table 1) with some differences. For example, the median time from initial diagnosis was shorter for patients receiving enzalutamide in the EU (67.1 months) compared with NA (89.9 months) and the proportion with a lower pain score was higher (BPI-SF, question 3: < 4). A lower proportion of EU patients had a high total Gleason score (8–10) than NA patients (44.0% vs 50.6%). Cardiac disease was less prevalent in EU than NA patients, while more had received more than two lines of prior hormonal therapy or chemotherapy. Prior and concomitant corticosteroid use, as well as concomitant use of bone protective agents (zoledronic acid), was lower in EU than NA patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

The patients’ baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristic | EU | NA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzalutamide (n = 461) | Placebo (n = 223) | Total (n = 684) | Enzalutamide (n = 263) | Placebo (n = 132) | Total (n = 395) | |

| Mean (sd) age, years | 68.5 (7.46) | 67.7 (7.88) | 68.2 (7.60) | 69.2 (8.70) | 69.7 (9.34) | 69.4 (8.91) |

| Median time from initial diagnosis, months | 67.1 | 72.0 | 68.9 | 89.9 | 67.3 | 78.0 |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||||

| 0–1 | 433 (93.9) | 206 (92.4) | 639 (93.4) | 237 (90.1) | 125 (94.7) | 362 (91.6) |

| 2 | 28 (6.1) | 17 (7.6) | 45 (6.6) | 26 (9.9) | 7 (5.3) | 33 (8.4) |

| Pain score, n (%) | ||||||

| <4 | 339 (73.5) | 169 (75.8) | 508 (74.3) | 186 (70.7) | 88 (66.7) | 274 (69.4) |

| ≥4 | 122 (26.5) | 54 (24.2) | 176 (25.7) | 77 (29.3) | 44 (33.3) | 121 (30.6) |

| Total Gleason score category, n (%) | ||||||

| Low (2–4) | 4 (0.9) | 6 (2.7) | 10 (1.5) | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.3) |

| Medium (5–7) | 202 (43.8) | 97 (43.5) | 299 (43.7) | 112 (42.6) | 56 (42.4) | 168 (42.5) |

| High (8–10) | 201 (43.6) | 100 (44.8) | 301 (44.0) | 131 (49.8) | 69 (52.3) | 200 (50.6) |

| Median total Gleason score | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| Median PSA level, ng/mL | 109.5 | 123.1 | 112.5 | 110.2 | 131.2 | 113.6 |

| Median LDH, U/L | 208.0 | 207.0 | 208.0 | 212.0 | 219.0 | 213.0 |

| Visceral disease (liver or lung), n (%) | 106 (23.0) | 45 (20.2) | 151 (22.1) | 73 (27.8) | 32 (24.2) | 105 (26.6) |

| Bone lesions, n (%) | ||||||

| 0–≤20 | 292 (63.3) | 146 (65.5) | 438 (64.0) | 161 (61.2) | 77 (58.3) | 238 (60.3) |

| >20 | 169 (36.7) | 77 (34.5) | 246 (36.0) | 102 (38.8) | 55 (41.7) | 157 (39.7) |

| Cardiac disease, n (%) | ||||||

| NYHA class ≤III | 32 (6.9) | 17 (7.6) | 49 (7.2) | 63 (24.0) | 29 (22.0) | 92 (23.3) |

| No cardiac disease | 429 (93.1) | 206 (92.4) | 635 (92.8) | 200 (76.0) | 103 (78.0) | 303 (76.7) |

| Prior corticosteroid use, n (%)* | 137 (29.7) | 63 (28.3) | 200 (29.2) | 85 (32.3) | 49 (37.1) | 134 (33.9) |

| Prior hormonal therapy, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 216 (46.9) | 96 (43.0) | 312 (45.6) | 145 (55.1) | 71 (53.8) | 216 (54.7) |

| >2 | 245 (53.1) | 127 (57.0) | 372 (54.4) | 118 (44.9) | 61 (46.2) | 179 (45.3) |

| Mean LHRH duration, months | 25.9 | 27.6 | 26.4 | 27.2 | 27.3 | 27.2 |

| Prior chemotherapy, n (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 330 (71.6) | 158 (70.9) | 488 (71.3) | 190 (72.2) | 102 (77.3) | 292 (73.9) |

| ≥2 | 131 (28.4) | 65 (29.1) | 196 (28.7) | 73 (27.8) | 30 (22.7) | 103 (26.1) |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LHRH, luteinising hormone-releasing hormone; NYHA, New York Heart Association. *Based on medical review to identify oral systemic corticosteroids for prostate cancer.

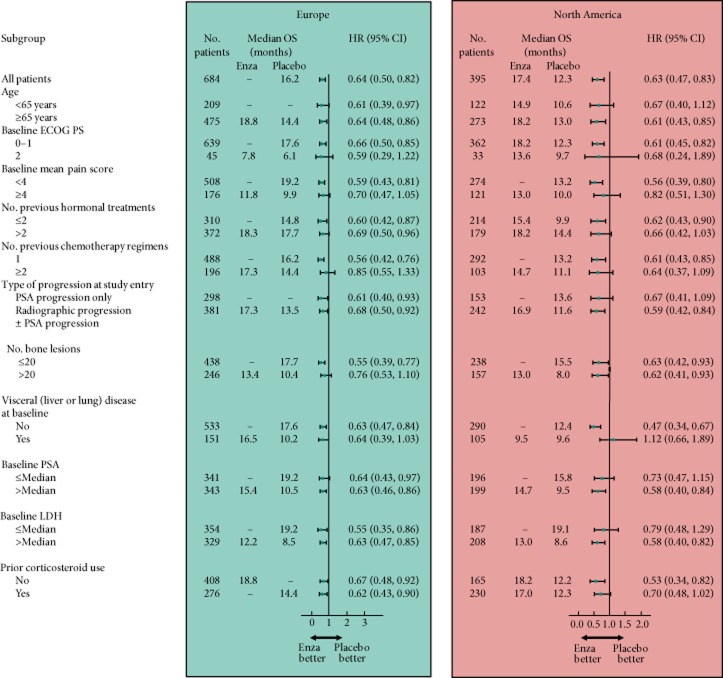

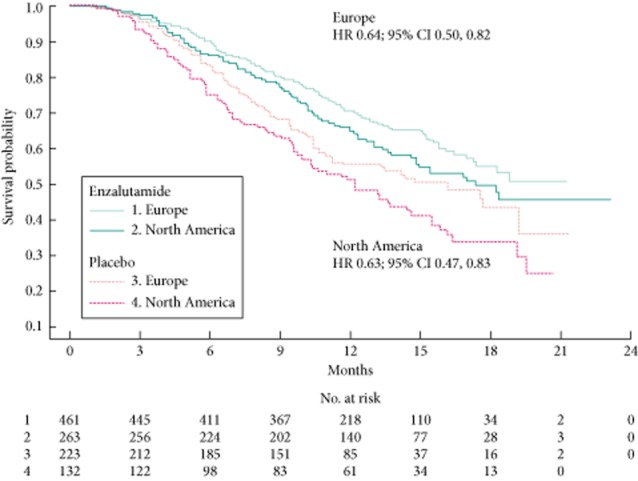

Enzalutamide significantly improved OS compared with placebo in both regional groups (Fig. 1) but the median OS in EU patients (enzalutamide, not yet reached; placebo, 16.2 months) was longer in both treatment groups compared with NA patients (enzalutamide, 17.4 months; placebo, 12.3 months). The relative treatment effect was similar across the two regions: HRs (95% CIs) were 0.64 (0.50, 0.82) for EU patients and 0.63 (0.47, 0.83) for NA patients. There was a difference of 1.9 months in median duration of follow-up (reverse Kaplan–Meier methodology) between regions (EU, 13.7 months; NA, 15.6 months), with no significant differences between study arms within each region. Maximal follow-up was 21.3 months in EU and 23.2 months in NA. Analysis of the OS data by different subgroups showed consistent enzalutamide benefits across most subgroups in both regions (Fig. 2). For NA patients with visceral disease at baseline, median OS was similar with enzalutamide and placebo. Notable, however, is that there were no regional differences (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.76, 1.38) or region-by-arm interaction (HR 0.94; 95% CI 0.64, 1.38) after controlling for baseline prognostic factors in a multivariable Cox model. Each of the terms listed in the multivariate model was statistically significant (P < 0.05) except for baseline BPI-SF group (P = 0.0577), which was a randomisation stratification factor and should be included in the model by study design. The process for selection of the non-randomisation stratification terms (everything except ECOG PS and BPI-SF) was based on imbalance or potential for confounding across the regions. The fact that all terms listed were significant and the factors (region and region*treatment interaction) were not significant suggests that some of these terms were confounders to the apparent regional differences in OS.

Fig 1.

OS (unadjusted assessment) by region and by arm.

Fig 2.

Forest plots of OS by subgroup and by region. HRs are based on a non-stratified proportional-hazards model. Dashes indicate that the median time to death had not been reached for the indicated subgroup. The size of the circles is proportional to the size of the subgroup. The horizontal bars represent 95% CIs. Enza, enzalutamide; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

The benefit of enzalutamide over placebo was consistent across all secondary end points in patients in both regions, with significant improvements (P < 0.001) in PSA, soft tissue and HRQL responses, time to PSA progression and rPFS (Table 2). Similar relative treatment effects (enzalutamide vs placebo) were seen for both regions, except for time to first SRE where a significant improvement with enzalutamide was only seen in EU patients. Kaplan–Meier curves showing the benefits of enzalutamide vs placebo in both EU and NA patients for time to PSA progression, rPFS, time to first SRE and time to pain progression are available in the Online Supplementary Information in Figs. S1–S4.

Table 2.

Secondary end points: response and progression

| Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU | NA | |||

| Enzalutamide (n = 461) | Placebo (n = 223) | Enzalutamide (n = 263) | Placebo (n = 132) | |

| % of patients | ||||

| Patients with ≥1 post-baseline PSA assessment | 92.6 | 85.2 | 89.0 | 78.0 |

| Decrease ≥50%* | 55.0 | 1.6 | 51.3 | 1.9 |

| Decrease ≥90%* | 23.0 | 1.1 | 26.9 | 1.0 |

| Patients with measurable disease | 53.6 | 52.9 | 58.6 | 52.3 |

| CR or PR* | 29.1 | 5.1 | 26.6 | 2.9 |

| Patients with ≥1 post-baseline HRQL assessment† | 81.6 | 67.3 | 81.4 | 56.8 |

| HRQL response* | 44.1 | 18.7 | 42.1 | 17.3 |

| Progression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End point | EU | NA | ||||

| Enzalutamide (n = 461) | Placebo (n = 223) | HR | Enzalutamide (n = 263) | Placebo (n = 132) | HR | |

| Median (95% CI): | ||||||

| Time to PSA progression, months | 8.2 (5.7, 8.3) | 3.0 (2.8, 3.7) | 0.28* (0.22, 0.36) | 8.3 (5.8, 8.4) | 3.7 (3.0, 5.6) | 0.26* (0.17, 0.40) |

| rPFS, months | 8.5 (8.2, 10.5) | 2.9 (2.8, 4.5) | 0.38* (0.32, 0.47) | 8.3 (5.9, 9.7) | 2.9 (2.8, 3.6) | 0.43* (0.34, 0.55) |

| Time to first SRE, months | 17.4 (14.1, NYR) | 11.9 (9.0, 15.2) | 0.56* (0.43, 0.73) | 16.7 (13.6, NYR) | 18.2 (8.6, NYR) | 0.79†† (0.56, 1.12) |

CR, complete response; NYR, not yet reached; PR, partial response. *P < 0.001 for enzalutamide vs placebo. †Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate questionnaire. ††P = 0.185 for enzalutamide vs placebo.

Although similar proportions of patients received a subsequent line of therapy on disease progression, the specific therapies administered were different in the two regions (Table 3). Specifically, more EU than NA patients randomised to placebo subsequently received abiraterone (30.5% vs 19.7%), whereas patients randomised to enzalutamide had similar subsequent exposure to abiraterone (21.7% EU vs 22.8% NA). Fewer EU than NA patients received cabazitaxel after enzalutamide (6.5% vs 15.6%) and after placebo (9.9% vs 20.5%).

Table 3.

Subsequent therapy on disease progression

| EU | NA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzalutamide (n = 461) | Placebo (n = 223) | Enzalutamide (n = 263) | Placebo (n = 132) | |

| Therapy | % of patients | |||

| Total | 41.0 | 62.3 | 46.4 | 61.4 |

| Abiraterone acetate | 21.7 | 30.5 | 22.8 | 19.7 |

| Cabazitaxel | 6.5 | 9.9 | 15.6 | 20.5 |

| Docetaxel | 8.9 | 15.7 | 8.7 | 15.2 |

| Mitoxantrone | 2.0 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 6.8 |

The overall safety profile of enzalutamide vs placebo was similar between the two regions (Table 4) for the overall number of adverse events (AEs)/serious AEs. Enzalutamide-treated patients in EU and NA had a lower incidence of AEs of grade ≥3 vs placebo. A slightly lower rate of discontinuations due to AEs was seen in the EU group. AEs of interest included seizure (four [0.87%] EU patients and one [0.38%] NA patient [Table 4 ]). Nausea, fatigue, anorexia, back pain, constipation and diarrhoea were reported by ≥20% of patients in both EU and NA (Online Supplementary Information Table S2). Nausea occurred at an incidence of 28% (enzalutamide) vs 39% (placebo) in EU and 40% (enzalutamide) vs 43% (placebo) in NA. Incidence of fatigue was 25% (enzalutamide) vs 22% (placebo) in EU and 48% (enzalutamide) vs 42% (placebo) in NA. Hot flushes occurred in enzalutamide patients at a rate ≥5% over placebo for both EU and NA patients. There were some differences between the regions in the incidence of specific AEs. For the NA enzalutamide group, several AEs occurred at an incidence ≥5% over placebo, including fatigue, diarrhoea, arthralgia, headache and muscular weakness, whereas in the EU enzalutamide group the incidence of these events was similar to placebo.

Table 4.

Summary of AEs

| EU (n = 684) | NA (n = 395) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzalutamide (n = 461) | Placebo (n = 223) | Enzalutamide (n = 263) | Placebo (n = 132) | |||||

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| AE | % of patients | |||||||

| ≥1 AE | 97.8 | 45.3 | 98.2 | 50.7 | 98.5 | 46.4 | 98.5 | 58.3 |

| Any serious AE | 34.1 | 28.6 | 39.5 | 33.2 | 31.2 | 27.0 | 36.4 | 34.1 |

| Discontinuation due to AE | 6.1 | 3.5 | 8.1 | 5.4 | 10.3 | 6.5 | 13.6 | 10.6 |

| AE leading to death | 2.6 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| AE of interest | ||||||||

| Any cardiac disorder | 5.6 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 7.2 | 0.8 | 12.1 | 3.8 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Abnormality on liver function testing | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 1.5 |

| Seizure* | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

*Events of seizure were reported in three EU patients and one NA patient at the pre-specified interim analysis. In the AFFIRM manuscript, these four events and one event in an Australian patient were included for a total of five patients 6. Subsequently, one additional patient (EU) was identified with an event term ‘vasovagal syndrome’ with features suggestive of seizure. Thus, five patients with an event of seizure are included in these data for EU and NA patients. The overall incidence of seizure in the AFFIRM analysis population was ≤0.9%.

Discussion

Differences in prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment patterns exist between EU and NA. The present post hoc exploratory analysis was performed to assess the outcomes of patients treated in the phase III registration trial of enzalutamide vs placebo (AFFIRM) in EU and NA, recognising that the study was not powered or designed to assess (or account for) regional differences at baseline. The results showed that the OS benefit provided by enzalutamide relative to placebo was of the same degree in men with mCRPC who had progressed on docetaxel in both regions. The results are consistent with the findings for the overall study population reported previously 6.

A similar outcome was seen for all secondary end points analysed, which included a range of early measures of response and progression as per the recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 2 24. The same parallel improvements in OS and in all secondary end points analysed is consistent with the results reported with other approved agents for post-chemotherapy treated mCRPC. Considering OS, the HR (95% CI) was 0.68 (0.56, 0.83) for NA and 0.80 (0.64, 1.00) for other regions, in the final analysis of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone vs placebo plus prednisone (COU-AA-301) 25,26. Overall OS and PFS results in the phase III trial of cabazitaxel were also comparable with the subgroup analysis of 90 patients from French centres 27.

Since the advent of PSA-based detection and screening there has been a shift towards diagnosis at an earlier stage and grade. In a study of men with clinically localised prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy in EU and NA in the past 20 years, stage and grade shifts over time were different in the two regions, which may be due to different surgical practices or differences in prostate cancer characteristics (e.g. biopsy, Gleason sum) between the regions 9. Historically, management of low-risk localised disease is more conservative in EU, with a more radical treatment approach in NA 28. More broadly, there are differences between the regions in medical/health-economic systems. In contrast to NA, EU health care is typically socialised and patients do not usually pay for expensive new cancer drugs.

The median OS in both enzalutamide and placebo arms was longer in EU than NA patients (enzalutamide, not yet reached [EU] and 17.4 months [NA]; placebo, 16.2 months [EU] and 12.3 months [NA]). Potential, albeit unproven, explanations for this observation include differences in baseline characteristics and treatment patterns between the regions. These differences include lower pain scores and a lesser presence of cardiac disease in EU patients, and higher use of prior and concomitant systemic corticosteroids, thought to reflect more extensive illness 29, and concomitant use of bone protective agents, in the NA group. Use of more than two lines of previous hormonal therapy or chemotherapy was also identified in more EU patients at baseline. Further exploration of these differences was limited by the small sample sizes of the various subgroups. The differing baseline severity across the regions (Table 1) could be evidence for lead-time bias and partially explain the observed differences in OS. Further differences in outcome could be related to the time when chemotherapy was offered, whether steroids were continued or not, and when physicians considered protocol therapy. In addition, some differences were seen in post-study treatment, e.g. higher cabazitaxel use in NA, perhaps reflecting the availability of cabazitaxel in NA before EU. Furthermore, identifying putative confounders that negate the apparent differences in OS between the regions neither implies such differences do not exist, nor that the regional variations in clinical practice do not drive differences in these confounders, thereby having implications on survival rates between the two regions. As our present results are based on a post hoc analysis and the AFFIRM study was not designed to investigate regional difference, our analysis cannot provide a definitive answer.

Differences were also seen between the regions in the secondary end point of time to first SRE, although the HR was <1 for both regions. Enzalutamide significantly improved median time to first SRE compared with placebo in EU patients (17.4 vs 11.9 months; P < 0.001), whereas there was no significant improvement in NA patients (16.7 vs 18.2 months; P = 0.185). The higher concomitant use of bone protective agents by NA patients (zoledronic acid: EU 35.2%; NA 48.6%) may have had some influence on this. The observed differences in baseline characteristics most likely reflect diagnosis and management practice patterns in the earlier stages of the disease noted above, most of which would have occurred sometime before patients developed CRPC, making it difficult to fully assess the likely impact on the results seen.

The tolerability profile of enzalutamide vs placebo was generally comparable between the two regions and consistent with tolerability in the overall AFFIRM trial population 6. Hot flushes were reported at a higher rate with enzalutamide than placebo (≥5% difference) in both EU and NA patients, consistent with reports from the original AFFIRM analysis 6. The apparent difference between the regions in the incidence of fatigue (>5% between enzalutamide and placebo in NA patients but not in EU patients) may be due to an artefact of the reported verbatim keywords (e.g. ‘fatigue’ vs ‘asthenia’) used in the two regions to describe general fatigue symptoms but resulting in different Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities codes. Another possibility is that increased rates of fatigue in NA patients were related to higher baseline use of steroids. Cases of seizure were reported in a small number of patients (four EU patients [0.87%] and one NA patient [0.38%] taking enzalutamide).

In conclusion, enzalutamide significantly prolonged survival in EU and NA men with mCRPC after docetaxel. The observed treatment benefit and safety profile from the two regions were consistent with the overall findings from the AFFIRM study.

Acknowledgments

The authors had full access to the data and participated in reviewing and interpreting the data and paper. They would like to thank Karen Brayshaw, PhD, at Complete HealthVizion, for assistance with writing and revising the draft manuscript, based on detailed discussion and feedback from all authors. Writing assistance was funded by Astellas Pharma, Inc and Medivation, Inc. Primary responsibility for opinions, conclusions and interpretation of data lies with the authors. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Glossary

- AE

adverse event

- AR

androgen receptor

- BPI-SF

Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form

- ECOG(PS)

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (performance status)

- EU

Europe/European

- FACT-P

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate

- HR

hazard ratio

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- mCRPC

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

- NA

North America/North American

- OS

overall survival

- rPFS

radiographic progression-free survival

- SRE

skeletal-related event

Conflict of Interest

A.S.M. has received consulting fees from Medivation, Astellas, Janssen-Cilag, Bayer, Roche, Ipsen, Novartis and Amgen, and payment for Speaker Bureau from Novartis, Bayer, Janssen-Cilag, Astellas, Ipsen, GlaxoSmithKline, Hexal and Amgen.

H.I.S. has received funding from Medivation and Veridex, consulting fees from Millennium, Orion/Endo, and Sanofi-Aventis, travel support from Medivation, Millennium, Orion/Endo, Sanofi-Aventis and AstraZeneca, and fees for participation in review activities from AstraZeneca, and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson.

J.B. has received fees as an advisory board member for Astellas, Amgen, Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayer, Ipsen and Takeda.

K.M. has received consulting fees from Medivation, Astellas, Janssen-Cilag, Bayer, Roche, Novartis and Amgen, fees for participation in review activities from Bayer, and payment for Speaker Bureau from Novartis, Bayer, Janssen-Cilag, Astellas and Amgen.

P.F.A.M. has received fees as an advisory board member for Astellas, Amgen, Janssen, Bayer, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Dendreon.

A.S. is a company consultant for GE Healthcare and Novartis, has received speaker honoraria from Amgen and Novartis, has participated in trials for MEDAC, Photocure, Immatics, Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, Amgen and Bayer, and has received research grants from Immatics.

C.N.S. has received consulting fees from Astellas, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi-Aventis, Amgen and Millennium.

K.F. has received fees as an advisory board member for Astellas, Amgen, Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayer, Orion, Ipsen, Takeda and Dendreon.

M.H. is an employee of Medivation and owns stock in Medivation.

B.F and G.P.H. are employees of Astellas.

J.dB. has received consulting fees and travel support from Astellas and Medivation.

R.dW. has received consulting fees from Astellas, Millennium, Janssen and Sanofi.

Supporting Information

Fig. S1 Time to prostate-specific antigen progression for European (EU) and North American (NA) patients.

Fig. S2 Radiographic progression-free survival for EU and NA patients.

Fig. S3 Time to first skeletal-related event for EU and NA patients.

Fig. S4 Time to pain progression for EU and NA patients.

Table S1 Definition of study end points.

Table S2 Most common adverse events (AEs, ≥ 10% in any group).

References

- Merseburger AS, Bellmunt J, Jenkins C, Parker C, Fitzpatrick JM. Perspectives on treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18:558–567. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8253–8261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merseburger AS, Kuczyk MA, Wolff JM. [Pathophysiology and therapy of castration-resistant prostate cancer] Urologe A. 2013;52:219–225. doi: 10.1007/s00120-012-3054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massard C, Fizazi K. Targeting continued androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3876–3883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A, Pfister D, Merseburger A, Bartsch G. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: where we stand in 2013 and what urologists should know. Eur Urol. 2013;64:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlmann CH, Merseburger AS, Suttmann H. Novel options for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2012;30:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0796-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallina A, Chun FK, Suardi N. Comparison of stage migration patterns between Europe and the USA: an analysis of 11 350 men treated with radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;101:1513–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwich A, Hugosson J, de Reijke T, Wiegel T, Fizazi K, Kataja V. Prostate cancer: ESMO Consensus Conference Guidelines 2012. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1141–1162. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J. 2013. EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Available at: http://www.uroweb.org/guidelines/online-guidelines/. Accessed 11 March 2014.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2013. NCCN Prostate Cancer Guidelines. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed 11 March 2014.

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;59:572–583. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A, Abrahamsson PA, Artibani W. Early detection of prostate cancer: European Association of Urology recommendation. Eur Urol. 2013;64:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2013;190:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audenet F, Lejay V, Mejean A. [Are therapeutics decisions homogeneous in multidisciplinary onco-urology staff meeting? Comparison of therapeutic options taken in four departments from Paris] Prog Urol. 2012;22:433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg CN, Baskin-Bey ES, Watson M, Worsfold A, Rider A, Tombal B. Treatment patterns and characteristics of European patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2013;13:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altavilla A, Iacovelli R, Procopio G, Cortesi E. Post-docetaxel therapy in castration resistant prostate cancer – the forest is growing in the desert. Ther Adv Urol. 2012;4:107–111. doi: 10.1177/1756287212440302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marech I, Vacca A, Ranieri G, Gnoni A, Dammacco F. Novel strategies in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer (Review) Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1313–1320. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne H, Bahl A, Mason M, Troup J, de Bono J. Optimizing the care of patients with advanced prostate cancer in the UK: current challenges and future opportunities. BJU Int. 2012;110:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JM, Mason M. Drivers for change in the management of prostate cancer – guidelines and new treatment techniques. BJU Int. 2012;109(Suppl. 6):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autio KA, Scher HI, Morris MJ. Therapeutic strategies for bone metastases and their clinical sequelae in prostate cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:174–188. doi: 10.1007/s11864-012-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JA, Botteman MF. Health-economic review of zoledronic acid for the management of skeletal-related events in bone-metastatic prostate cancer. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12:425–437. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1148–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:983–992. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouessel D, Oudard S, Gravis G, Priou F, Shen L, Culine S. [Cabazitaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: the TROPIC study in France] Bull Cancer. 2012;99:731–741. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2012.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey GP, McPhail S, Fowler S, McIntosh G, Gillatt D, Parker CC. Initial management of low-risk localized prostate cancer in the UK: analysis of the British Association of Urological Surgeons Cancer Registry. BJU Int. 2010;106:1161–1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F. Impact of on-study corticosteroid use on efficacy and safety in the phase III AFFIRM study of enzalutamide (ENZA), an androgen receptor inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl):abs 6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Time to prostate-specific antigen progression for European (EU) and North American (NA) patients.

Fig. S2 Radiographic progression-free survival for EU and NA patients.

Fig. S3 Time to first skeletal-related event for EU and NA patients.

Fig. S4 Time to pain progression for EU and NA patients.

Table S1 Definition of study end points.

Table S2 Most common adverse events (AEs, ≥ 10% in any group).