Abstract

Purpose

Lenalidomide is a novel therapeutic agent with uncertain mechanism of action that is clinically active in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and multiple myeloma (MM). Application of high (MM) and low (MDS) doses of lenalidomide has been reported to have clinical activity in CLL. Herein, we highlight life-threatening tumor flare when higher doses of lenalidomide are administered to patients with CLL and provide a potential mechanism for its occurrence.

Patients and Methods

Four patients with relapsed CLL were treated with lenalidomide (25 mg/d for 21 days of a 28-day cycle). Serious adverse events including tumor flare and tumor lysis are summarized. In vitro studies examining drug-induced apoptosis and activation of CLL cells were also performed.

Results

Four consecutive patients were treated with lenalidomide; all had serious adverse events. Tumor flare was observed in three patients and was characterized by dramatic and painful lymph node enlargement resulting in hospitalization of two patients, with one fatal outcome. Another patient developed sepsis and renal failure. In vitro studies demonstrated lenalidomide-induced B-cell activation (upregulation of CD40 and CD86) corresponding to degree of tumor flare, possibly explaining the tumor flare observation.

Conclusion

Lenalidomide administered at 25 mg/d in relapsed CLL is associated with unacceptable toxicity; the rapid onset and adverse clinical effects of tumor flare represent a significant limitation of lenalidomide use in CLL at this dose. Drug-associated B-cell activation may contribute to this adverse event. Future studies with lenalidomide in CLL should focus on understanding this toxicity, investigating patients at risk, and investigating alternative safer dosing schedules.

INTRODUCTION

Lenalidomide is a synthetic analog of thalidomide that lacks many of its unfavorable properties including neurotoxicity. While the mechanism of action of lenalidomide is uncertain, in various preclinical systems it been shown to downregulate tumor necrosis factor-α,1 alter tumor microenvironment,2 enhance antibody dependent cytotoxicity,3,4 favorably modulate T-cell function,3,5 and upregulate expression of select tumor suppressor genes such as SPARC.6 Significant activity of lenalidomide has been observed in both del(5q) myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)7,8 and multiple myeloma.9–11 In phase I/II studies in these diseases, dose-dependent myelosuppression has been observed with doses of 25 mg per day in multiple myeloma,7 and 10 mg in MDS9 being well-tolerated. In neither multiple myeloma nor MDS have the toxicities of tumor flare or signs and symptoms of cytokine release been observed.

Two recent phase II studies have demonstrated that lenalidomide has clinical activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The first was a phase II study of 45 previously treated patients with CLL who received 25 mg of lenalidomide orally daily on days 1 through 21 of a 28-day cycle.12 This regimen had a 47% overall response rate and a 9% complete response rate. Common toxicities in this study were fatigue, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. However, tumor flare reactions occurred in 58% of patients (grade 1 to 2 in 50%; grade 3–4 in 8%). Flare was described clinically as painful enlargement of lymph nodes and/or spleen with associated low-grade fever and rash, and was managed with either nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or prednisone. Atypical tumor lysis syndrome associated with renal insufficiency was also noted in two additional patients. There was also one death, attributed to worsening congestive heart failure. The second study13 included 35 patients with CLL, with 22 assessable for response and toxicity. Patients received lenalidomide 10 mg daily for 28 days with dose escalation to a maximum of 25 mg daily as tolerated. The overall response rate was 32%, with one complete response. Tumor flare was observed in 27% of patients. There were no patients reported to have tumor lysis syndrome.13

Our institutional experience with lenalidomide in four patients given 25 mg/d as in the previously reported schedule12 was complicated by frequent, life-threatening tumor flare that was fatal in one patient. We describe the toxicities in detail herein and then extend these clinical observations to the laboratory, identifying a potential mechanism for this serious toxicity.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

From January 2007 to June 2007 we treated four patients with relapsed and refractory CLL with lenalidomide at Ohio State University. One patient (patient 1) with highly refractory CLL with extensive bulky disease was treated with lenalidomide with therapeutic intent for cytoreduction in preparation for an HLA-identical sibling allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Other effective investigational therapy14 could not be administered because insurance coverage was denied. Given the previous reported phase II study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology suggesting efficacy and safety,12 the patient was treated with lenalidomide off study. Three patients (patients 2, 3, and 4) were treated as part of a subsequent institutional review board–approved phase I study of lenalidomide for previously treated CLL with detailed monitoring described due to the initial (patient 1) experience with lenalidomide in CLL at our institution. All three patients provided written informed consent. Requirements for enrollment included relapsed disease, platelets of 50 × 109/L, an absolute neutrophil count of 1 × 109/L, and absence of infection. Therapy was administered at 25 mg/d for 21 days with a 7-day rest period (one cycle). Intensified monitoring was instituted given the possible risk of tumor flare; all patients on the trial were monitored daily in our outpatient clinic by one of the attending CLL physicians for the first 5 days of therapy and weekly thereafter. Prophylactic corticosteroids were administered to all patients for the first 14 days of therapy (12 mg of dexamethasone days 1 through 7, then 4 mg days 8 through 14). Patient 1 had received prophylactic prednisone as detailed in the case summary below.

In Vitro Studies, Lenalidomide Extraction, and Purification

The lenalidomide used for the in vitro CLL experiments was extracted from commercial capsules donated from a patient who was no longer undergoing treatment. The powder was stirred in a mixture of 250 mL of ethyl acetate with 10 mL of triethylamine for 3 hours and then filtered. This process was repeated with the residual powder two additional times. The collected organic solvent was dried to yield a white solid, which was used for biochemical testing. The purity of capsule-extracted lenalidomide was evaluated with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) in the Ohio State University pharmacoanalytical shared resource. The NMR spectra contained only lenalidomide resonance peaks, and no indication of contaminating materials. LC/MS chromatograms and mass spectra were identical to those obtained with analytic standard material obtained from Celgene Inc. When analyzed in a validated quantitative LC/MS/MS method, the extracted material was indistinguishable from the standard material throughout the linear range (0.25 to 1,000 nmol/L).

CLL Cell Isolation

Blood was obtained from patients with CLL with informed consent under a separate institutional review board–approved tissue banking protocol. These patients were separate from those treated on the clinical trial (who all had very little blood or bone marrow disease). All patients had CLL as described and demographics are described in online-only Table A1.15 CLL B cells were isolated from freshly donated blood using ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque Plus; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) with enrichment using the Rosette-Sep kit from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human serum (HS, Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 100 U/mL penicillin/100 ug/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Assessment of Surface Antigen Expression by Flow Cytometry

Immunophenotyping was performed to determine the absolute number and relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD40, CD80, CD86, CD95, and HLA-DR on CLL cells. Cells were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes, incubated at 4°C in dark for 30 minutes with 10 μL appropriate antibody and then washed with 1 mL cold phosphate-buffered saline. After decanting, 1 mL cold phosphate-buffered saline was added for flow cytometry analysis on an EPICS-XL (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL). Antibodies used were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA): CD40 (BD555589), CD80 (BD340294), CD86 (BD555658), CD95 (BD340480), and HLA-DR (BD347363). Ten thousand events were collected from each sample and data was analyzed by Expo32 software package (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL).

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s directions and converted to cDNA with SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed using custom designed primers for CD80 and CD86 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The housekeeping gene TATA binding protein (TBP) was used for normalization purposes given its optimal role for B-cell studies.16 The expression of CD40 and CD86 relative to the housekeeping gene TBP was calculated by plotting the cycle number (Ct) and the average relative expression for each group was determined using the comparative method (2ΔCt).17

Statistics

SPSS software (version 13.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analysis. Nonparametric paired Wilcoxon signed ranked tests were performed to examine both the proportion and mean fluorescence intensity change of cells expressing specific antigens following treatment with lenalidomide or media for 48 hours. A paired t-test was used to evaluate if there was a change in delta Ct values between cells treated and not treated with lenalidomide. Delta Ct values were used in the calculation because they better meet the assumption of normality.

RESULTS

Lenalidomide Clinical Experience

Four patients were treated with lenalidomide at our institution for the primary indication of relapsed CLL. The clinical features of each of these patients are summarized in Table 1. The case summaries outlining drug-related toxicities for each patient are summarized in the following paragraphs.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics Prior to Lenalidomide Treatment

| Patient No. | Age (years) |

Performance Status | RAI Stage | WBC (× 109/L) |

LN (> 5 cm) |

Baseline Creatine (mg/dL) |

Creatine Clearance | No. of Prior Therapies | Fludarabine Refractory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56 | 1 | 4 | 197 | Yes | 0.86 | 45 | 4 | Yes |

| 2 | 55 | 1 | 4 | 3.2 | No | 1.34 | > 60 | 9 | Yes |

| 3 | 41 | 0 | 1 | 8.0 | Yes | 0.78 | > 60 | 4 | No |

| 4 | 51 | 0 | 1 | 3.7 | No | 1.13 | > 60 | 2 | Yes |

Patient 1 was referred to our institution for treatment of fludarabine- and chemotherapy- refractory CLL but was ineligible to participate on clinical trial due to insurance denial. He was prescribed lenalidomide 25 mg orally daily on the basis of published available data indicating its efficacy in CLL.12 The pretreatment WBC count was 197,000/mL and bulky adenopathy was present (mesenteric lymph node mass 6.4 cm × 17.8 cm). He received prednisone 20 mg daily for prevention of tumor flare and cytokine release. Three days after starting lenalidomide he inadvertently omitted the prednisone and rapidly developed abdominal and back pain, lethargy, weakness, hypoxia, and mental status changes. On hospital admission he had evidence of tumor lysis syndrome with hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, and an elevated LDH. Repeat computed tomography of the abdomen showed an increase in the mesenteric mass to 19.8 cm × 7.3 cm. Lenalidomide was discontinued and corticosteroids administered. His physical condition rapidly deteriorated as a result of tumor lysis syndrome, cytokine release syndrome, and marked peripheral blood lymphocytosis to 372,000/mL. Despite maximal medical support including leukapheresis and mechanical ventilation he died on hospital day 10 due to hypoxemic respiratoryfailure.

Patient 2 initiated lenalidomide on clinical trial at 25 mg/d and completed 21 days of therapy without signs or symptoms of tumor flare or tumor lysis. He was not neutropenic at the time of initiation of therapy. On day 25, he presented to an outside hospital with febrile neutropenia, sepsis syndrome secondary to Pseudomonas aeruginosa requiring pressor support, and rapidly developed multiorgan failure. He fully recovered after a 10-day hospitalization and was taken off study, as progressive disease was noted soon after hospital discharge.

Patient 3 initiated lenalidomide on clinical trial at 25 mg/d and tolerated the first 7 days of therapy without complications; however on day 8 of therapy during steroid taper he developed tumor flare characterized by enlarging lymph nodes, severe back and abdominal pain, fever, and rash. These symptoms resolved with discontinuation of lenalidomide and re-escalation of steroids. Subsequent treatments have required continued dose reductions due to tumor flare to a tolerable dose of 5 mg every other day.

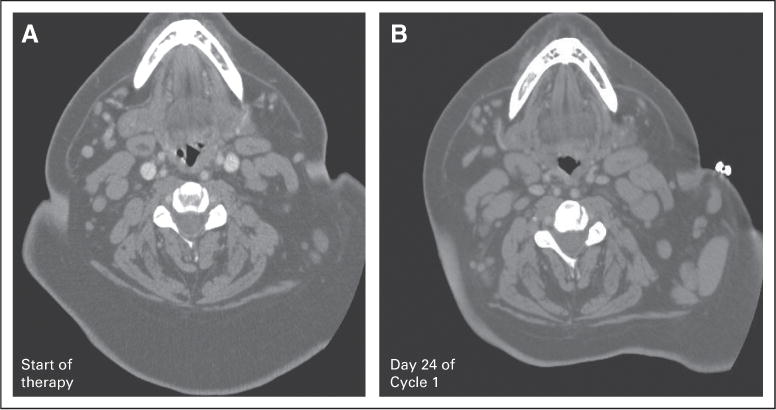

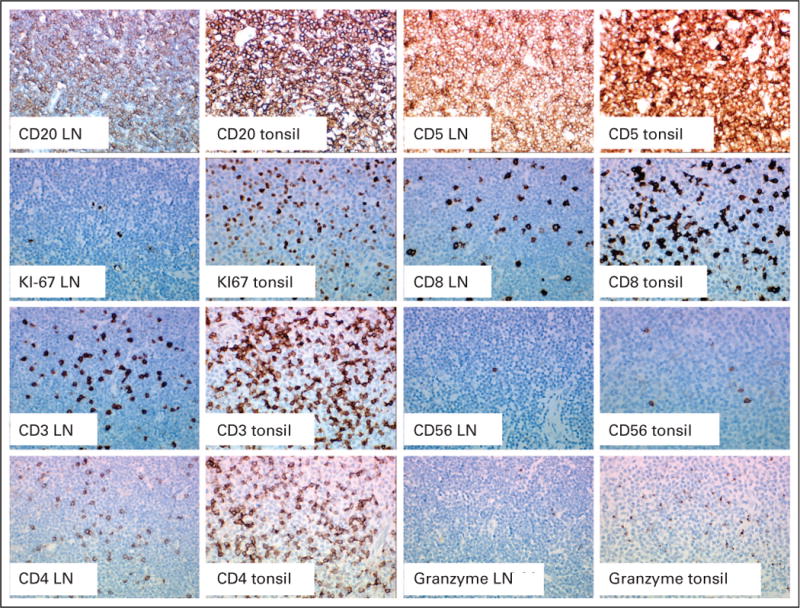

Patient 4 initiated lenalidomide at 25 mg/d and received days 1 through 21 of therapy. On day 28 he presented with dyspnea on recumbency and had new massive tonsillar hypertrophy with airway obstruction, as well as new supraclavicular and cervical lymphadenopathy (Fig 1). Therapy was discontinued, steroids were administered, and a tonsillectomy was performed. The excised tonsils showed involvement by CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia (Fig 2) without evidence of transformation. Comparison of this tonsil to a pretreatment excised lymph node demonstrated increased Ki-67 staining, increased CD3-positive, CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and granzyme-B–positive T-cells. CD56-positive natural killer cells were not increased in the excised tonsil.

Fig 1.

Patient 4 computed tomography scan of the neck: (A) at the start of lenalidomide therapy; (B) on day 24 of cycle 1.

Fig 2.

Pretreatment cervical lymph node and excised tonsil following lenalidomide treatment. These studies demonstrate increased Ki67 expression and CD3, CD4, CD8, granzyme B positive cells following lenalidomide treatment.

Lenalidomide Preclinical Experience

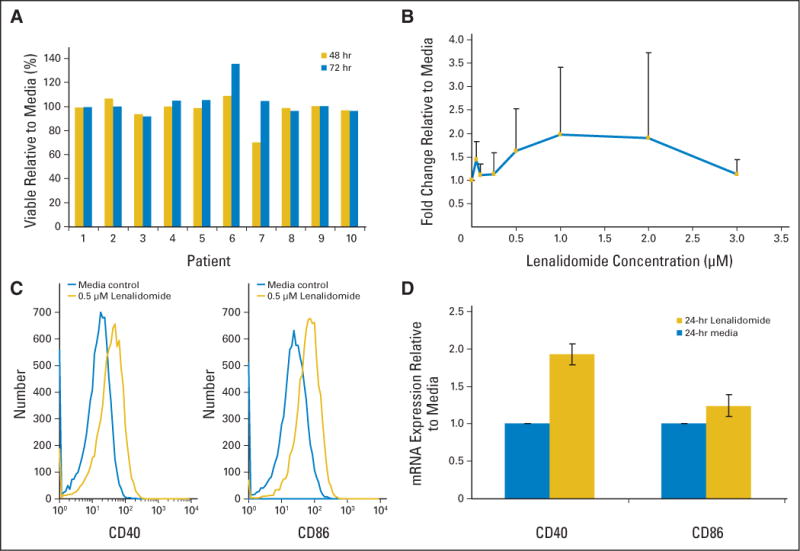

The clinical findings of tumor flare observed in these four patients are similar to the unique dose limiting toxicity observed with G3139 (Genasense, an anti–bcl-2 oligonucleotide) in CLL.18 Due to this toxicity, G3139 required lower dosing in subsequent phase III studies in CLL19 than was utilized in other malignancies.20–22 Several investigators have noted that CpG oligonucleotides, including G3139, promote upregulation of activation surface antigens on CLL cells that have the potential to make these cells immunogenic to autologous T-cells.23–26 We sought to determine if lenalidomide exerted any influence on primary CLL cells in vitro. Ten purified fresh CLL in vitro samples that were treated with pharmacologically attainable concentrations of lenalidomide demonstrated no apoptosis as shown in Figure 3A Given the observation of lymph node enlargement and symptoms of cytokine release at the time of tumor flare, we examined seven patient samples following lenalidomide treatment for evidence of CLL cell proliferation (measured incorporated tritiated thymidine uptake, n = 7 patients) and cytokine production (measured by supernatant level of IL-6 and TNF-α, n = 5 patients) and demonstrated no increases as compared to media control (data not shown). We next sought to determine if lenalidomide treatment in vitro at physiologically attainable concentrations promoted upregulation of B-cell activation markers including CD40, CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, and CD95. Here we observed both an increase in expression and/or upregulation of antigen expression on all patients tested. Most prominent was upregulation of antigens CD40 (22 of 24 patients; P < .001) and CD86 (10 of 17 patients; P = .0173) at 48 hours of incubation with lenalidomide as compared to media control. Similarly, the proportion of CLL cells expressing CD40 and CD86 antigens increased (23 of 24 patients; P < .001, and 17 of 17 patients; P < .001, respectively). This upregulation of activation markers increased proportionately with dose of lenalidomide up to 1 μmol/L as depicted for CD40 in Figure 3B. A representative case of CD40 and CD86 expression is shown in Figure 3C, and Table 2 presents all data. To determine if CD40 and CD86 surface receptor upregulation by lenalidomide was accompanied by increased transcriptional production of CD40 and CD86 mRNA, we performed quantitative TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction on media and lenalidomide-treated CLL cells. Figure 3D demonstrates significant (P = .004) increases in expression in CD40 as compared to media control. These data suggest that upregulation of CD40 occurs in part through a transcriptional mechanism.

Fig 3.

(A) Treatment of CLL cells ex vivo with lenalidomide (0.5 μmol/L) for 48 and 72 hours does not promote loss of viability in vitro. (B) Treatment of CLL cells ex vivo with lenalidomide results in dose dependent upregulation of the CD40 antigen. (C) Representative histograms show CD40 and CD86 expression increase on CLL cells after 48 hours 0.5 μM lenalidomide treatment in vitro. (D) CLL cell mRNA expression of CD40, but not CD86, is significantly increased after 24 hours of 0.5 μM lenalidomide treatment in vitro.

Table 2.

Fold Change in CD40 and CD86 in B-CLL Cells Treated With 0.5 juM Lenalidomide Compared With Media Control

| Positive Cells (%)

|

MFI

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL Patient No. | CD40 | CD86 | CD40 | CD86 |

| 1 | 1.66 | 1.96 | 1.13 | 1.01 |

|

| ||||

| 2 | 1.92 | 12.64 | 1.21 | 1.65 |

|

| ||||

| 3 | 1.65 | 1.49 | 1.12 | 1.30 |

|

| ||||

| 4 | 1.04 | 2.14 | 1.38 | 1.51 |

|

| ||||

| 5 | 6.81 | 1.32 | 1.21 | 1.25 |

|

| ||||

| 6 | 1.66 | 1.76 | 1.12 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| 7 | 1.95 | 1.25 | 1.12 | 0.94 |

|

| ||||

| 8 | 1.60 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 0.87 |

|

| ||||

| 9 | 2.21 | 2.34 | 1.22 | 2.58 |

|

| ||||

| 10 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 1.03 | 1.20 |

|

| ||||

| 11 | 1.00 | 1.93 | 1.22 | 0.93 |

|

| ||||

| 12 | 6.58 | 3.00 | 1.49 | 1.72 |

|

| ||||

| 13 | 4.60 | 3.30 | 1.10 | 1.17 |

|

| ||||

| 14 | 1.21 | 3.14 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

|

| ||||

| 15 | 2.17 | 13.71 | 1.19 | 1.16 |

|

| ||||

| 16 | 2.00 | 4.11 | 1.21 | 0.85 |

|

| ||||

| 17 | 2.22 | 2.80 | 1.13 | 1.18 |

|

| ||||

| 18 | 1.38 | ND | 1.67 | ND |

|

| ||||

| 19 | 1.90 | ND | 1.50 | ND |

|

| ||||

| 20 | 1.12 | ND | 1.08 | ND |

|

| ||||

| 21 | 5.40 | ND | 2.00 | ND |

|

| ||||

| 22 | 1.43 | ND | 1.00 | ND |

|

| ||||

| 23 | 2.00 | ND | 1.50 | ND |

|

| ||||

| 24 | 1.52 | ND | 1.05 | ND |

Abbreviations: CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ND, not determined.

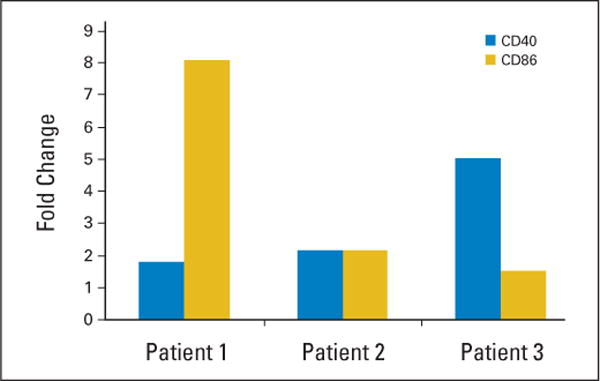

The observation that lenalidomide promotes upregulation of B-cell activation/costimulatory molecules, provides a potential mechanism for the observed tumor flare in vivo. We next sought to determine if the degree of B-cell activation observed in vitro correlated with the observed degree of tumor flare among patients treated with lenalidomide. Figure 4 demonstrates the fold increase in CD40 and CD86 expression on patents 1, 2, and 3, each of whom had pretreatment tumor cells available for analysis. Of note, patient 1 who had the greatest toxicity of lenalidomide had the greatest fold increase in CD86 and also CD40 expression. Patient 2 who had essentially no tumor flare had minimal increase in CD86 and CD40. Concurrent ex vivo treatment of CLL cells with 0.5 μmol/L dexamethasone, an agent that controls tumor flare symptoms, prevented upregulation of CD40 and CD86 (data not shown).

Fig 4.

CLL cells from patients 1, 2, and 3 were treated in vitro with 0.5 μM lenalidomide for 48 hours. Results shown are increase in percent of CD40 and CD86 positive cells relative to media control that is greatest in patient 1 and 3 who both had tumor flare.

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that lenalidomide therapy in CLL, utilizing the previously reported schedule of 25 mg/d for 21 consecutive days, is associated with unacceptable toxicity despite very careful daily observation in a CLL specialty clinic by physicians with extensive phase I experience. Three of four patients in this series developed serious tumor flare that required acute hospitalization in two, with one death. The fatal drug-related event occurred in a patient who had highly active CLL typical of most advanced stage patients with fludarabine-refractory disease, a patient population in which lenalidomide treatment off label maybe considered based on a published report.12 The fourth patient developed a sepsis syndrome, pulmonary insufficiency, and renal failure soon after completing the first cycle of therapy. This experience contrasts with a previous report of 45 patients where only three patients experienced grade 3 or 4 tumor flare without associated mortality.12 The data presented herein and corroborated by a recent letter by Celgene27 provide evidence that lenalidomide cannot be safely administered to patients with advanced-stage CLL utilizing the 25 mg/d schedule previously reported.12 Given that a lower reported incidence of tumor flare and no cases of tumor lysis were observed with the lower dose schedule of lenalidomide preliminarily reported by Ferrajoli et al,13 pursuit of a lower initial dose with stepped up dosing may be safer. Given the uncertainty at this time about the safety of lenalidomide administration in CLL, this agent should only be administered as part of institutional review board–approved clinical trials.

Of equal interest is the etiology of the tumor flare produced by lenalidomide. To date, no published reports are available relative to the in vitro effect of lenalidomide on primary CLL cells. A preliminary abstract suggested lenalidomide might upregulate CD80 and CD95 expression in CLL cells.28 Our data described herein extends this observation and demonstrates that lenalidomide does not directly promote apoptosis, proliferation, or cytokine production by CLL cells. However, lenalidomide does significantly promote upregulation of B-cell activation markers including CD40, CD80 CD86, HLA-DR, and CD95 in a dose-dependent fashion up to a concentration of 1 μmol/L. Upregulation of CD40 occurs in part through a transcriptional mechanism and is antagonized by dexamethasone, a treatment that effectively alleviates tumor flare in patients. Ex vivo lenalidomide treatment of CLL cells from patients enrolled on the trial demonstrated the greatest upregulation of CD86 and CD40 in the individual with the most dramatic tumor flare. While we did not examine the influence of other immune effector cells on activated CLL cells in vitro or ex vivo, such studies should be pursued. Of interest, we did observe both increased Ki67 staining and T-cell infiltration of CD3-positive, CD8-positive, granzyme-B– positive cells in the tonsil removed from patient 4 during his tumor flare as compared with a pretreatment lymph node. While the relationship of B-cell activation in CLL to lenalidomide toxicity observed herein is circumstantial at this time, future investigation of this in available animal models of CLL29,30 or in conjunction with phase I/II trials of this agent should be pursued. Given the variability of in vitro B-cell activation observed among the patients studied, which was greatest in patient 1 who died of tumor flare, correlation of the degree of ex vivo activation with toxicity, and efficacy of lenalidomide in vivo should be examined in subsequent clinical trials.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that lenalidomide administered at 25 mg/d for 21 days in patients with refractory CLL is associated with unacceptable toxicity including life-threatening tumor flare. The etiology of this tumor flare is uncertain at this time but may be related to B-cell activation. Future study of this phenomenon in CLL is warranted and ongoing by our group. Lenalidomide has demonstrated activity in CLL and thus a safe dosing schedule needs to be established prior to larger multicenter studies. Until this occurs, physicians should be discouraged from using lenalidomide to treat CLL patients outside of an institutional review board–approved clinical trial that incorporates close monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B Foundation, The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and The D. Warren Brown Foundation.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Robert D. Knight, Celgene (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: John C. Byrd, Celgene (U) Stock Ownership: Robert D. Knight, Celgene Honoraria: None Research Funding: William Blum, Celgene Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Leslie A. Andritsos, Amy J. Johnson, Gerard Lozanski, William Blum, Cheryl Kefauver, Farrukh Awan, Lisa L. Smith, Ching-Shih Chen, John C. Byrd

Financial support: William Blum, Robert D. Knight, John C. Byrd

Administrative support: Cheryl Kefauver, John C. Byrd

Provision of study materials or patients: Leslie A. Andritsos, Gerard Lozanski, William Blum, Cheryl Kefauver, Lisa L. Smith, Rosa Lapalombella, Sarah E. May, Da-Sheng Wang, Ching-Shih Chen, John C. Byrd

Collection and assembly of data: Leslie A. Andritsos, Amy J. Johnson, Gerard Lozanski, Lisa L. Smith, Rosa Lapalombella, Chelsey A. Raymond, John C. Byrd

Data analysis and interpretation: Amy J. Johnson, Gerard Lozanski, William Blum, Farrukh Awan, Lisa L. Smith, Rosa Lapalombella, Da-Sheng Wang, Robert D. Knight, Amy S. Ruppert, Amy Lehman, David Jarjoura, Ching-Shih Chen, John C. Byrd

Manuscript writing: Leslie A. Andritsos, Amy J. Johnson, Robert D. Knight, Ching-Shih Chen, John C. Byrd

Final approval of manuscript: Leslie A. Andritsos, Amy J. Johnson, Gerard Lozanski, William Blum, Cheryl Kefauver, Farrukh Awan, Lisa L. Smith, Rosa Lapalombella, Sarah E. May, Da-Sheng Wang, Robert D. Knight, Amy S. Ruppert, David Jarjoura, Ching-Shih Chen, John C. Byrd

References

- 1.Marriott JB, Clarke IA, Dredge K, et al. Thalidomide and its analogues have distinct and opposing effects on TNF-alpha and TNFR2 during co-stimulation of both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:75–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangiameli DP, Blansfield JA, Kachala S, et al. Combination therapy targeting the tumor microenvironment is effective in a model of human ocular melanoma. J Transl Med. 2007;5:38–46. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tai YT, Li XF, Catley L, et al. Immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide (CC-5013, IMiD3) augments anti-CD40 SGN-40-induced cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma: Clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11712–11720. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Reddy N, Holkova B, et al. Immunomodulatory drug CC-5013 or CC-4047 and rituximab enhance antitumor activity in a severe combined immunodeficient mouse lymphoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5984–5992. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeBlanc R, Hideshima T, Catley LP, et al. Immunomodulatory drug costimulates T cells via the B7-CD28 pathway. Blood. 2004;103:1787–1790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellagatti A, Jadersten M, Forsblom AM, et al. Lenalidomide inhibits the malignant clone and up-regulates the SPARC gene mapping to the commonly deleted region in 5q-syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11406–11411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610477104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.List A, Kurtin S, Roe DJ, et al. Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:549–557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1456–1465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Weller E, et al. Immunomodulatory drug CC-5013 overcomes drug resistance and is well tolerated in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100:3063–3067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajkumar SV, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, et al. Combination therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (Rev/Dex) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:4050–4053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanan-Khan A, Miller KC, Musial L, et al. Clinical efficacy of lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5343–5349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrajoli AOBS, Faderl SH, Wierda WG, et al. Lenalidomide induces complete and partial responses in patients with relapsed and treatment-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:305. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130120. abstr 305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrd JC, Lin TS, Dalton JT, et al. Flavopiridol administered using a pharmacologically derived schedule is associated with marked clinical efficacy in refractory, genetically high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:399–404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lossos IS, Czerwinski DK, Wechser MA, et al. Optimization of quantitative real-time RT-PCR parameters for the study of lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 2003;17:789–795. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien SM, Cunningham CC, Golenkov AK, et al. Phase I to II multicenter study of oblimersen sodium, a Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide, in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7697–7702. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien S, Moore JO, Boyd TE, et al. Randomized phase III trial of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide with or without oblimersen sodium (Bcl-2 antisense) in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1114–1120. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedikian AY, Millward M, Pehamberger H, et al. Bcl-2 antisense (oblimersen sodium) plus dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma: The Oblimersen Melanoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4738–4745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badros AZ, Goloubeva O, Rapoport AP, et al. Phase II study of G3139, a Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide, in combination with dexamethasone and thalidomide in relapsed multiple myeloma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4089–4099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcucci G, Stock W, Dai G, et al. Phase I study of oblimersen sodium, an antisense to Bcl-2, in untreated older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical activity. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3404–3411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jahrsdorfer B, Hartmann G, Racila E, et al. CpG DNA increases primary malignant B cell expression of costimulatory molecules and target antigens. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decker T, Schneller F, Kronschnabl M, et al. Immunostimulatory CpG-oligonucleotides induce functional high affinity IL-2 receptors on B-CLL cells: Costimulation with IL-2 results in a highly immunogenic phenotype. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:558–568. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker T, Schneller F, Sparwasser T, et al. Immunostimulatory CpG-oligonucleotides cause proliferation, cytokine production, and an immunogenic phenotype in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 2000;95:999–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro JE, Prada CE, Aguillon RA, et al. Thymidine-phosphorothioate oligonucleotides induce activation and apoptosis of CLL cells independently of CpG motifs or BCL-2 gene interference. Leukemia. 2006;20:680–688. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moutouh-de Parseval LA, Weiss L, DeLap RJ, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome/tumor flare reaction in lenalidomide-treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padmanabhan S, Wallace PK, Miller KC, et al. First clinical evidence of in vivo natural killer (NK) cell modulation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients (pts) treated with lenalidomide (L) Blood. 2006;108:2109. abstr 2109. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson AJ, Lucas DM, Muthusamy N, et al. Characterization of the TCL-1 transgenic mouse as a preclinical drug development tool for human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:1334–1338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-011213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bichi R, Shinton SA, Martin ES, et al. Human chronic lymphocytic leukemia modeled in mouse by targeted TCL1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6955–6960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102181599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.