Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare neuroendocrine neoplasms, which have been increasing in incidence in recent years, largely due to the increased use of diagnostic imaging.1, 2 As a result, PNETs now constitute up to 10% of all pancreatic tumors.2, 3 Non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NF-PNETs) are those tumors that do not produce a hormonal hypersecretion syndrome2 and comprise 47-90% of all PNETs,2-4 with an incidental detection rate of 35-88%.5, 6 Because of the lack of hormonally-related clinical symptoms, patients tend to be diagnosed later in the course of their disease.7, 8 Overall, as compared to functional PNETs, NF-PNETs have a worse prognosis and poorer survival, but whether this is due to a difference in biologic aggressiveness or later diagnosis is unclear.8-14

The mainstay of treatment for curing NF-PNETs is oncologic resection.2 However, localized resection, such as enucleation and central pancreatectomy, may be carefully considered in incidentally found NF-PNETs <2cm, which have a low risk of malignancy, or in patients with hereditary syndromes at high risk of multifocal/recurrent disease, including multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) and Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL).1, 2, 15 Long-term outcomes after surgery vary widely, with recurrence rates ranging from 17% to 76% 16-19 and overall survival ranging from 1.9 to 10.3 years,20, 21 largely depending on the extent of disease and the biologic characteristics of the tumor. Median time to recurrence has been reported to be 2 to 3.3 years. 16, 18, 22, 23

While there have been no large-scale studies specifically investigating the factors that correlate with NF-PNET recurrence, there have been several studies identifying prognostic factors for poor overall survival. These include both clinical and histopathological factors, including weight loss21, older age24, lymph node and distant metastases21, 24, poor differentiation status21, high grade24, Ki-67 index>5%21, WHO class25, and positive margins10. Genomics studies have also reported the absence of MEN1, DAXX, and ATRX mutations26 and differential expression of such genes as KIT27 and FGF13, TSC2, and PTEN28 as correlating with worse survival.

The role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in tumor initiation and progression is complex, with varied pro- and anti-tumor-promoting effects in different types of cancers.29 Previous studies have demonstrated that tumor-promoting behaviors are triggered in response to peri-tumoral hypoxia, which results in the production of a number of mitogens, growth factors, and enzymes that promote angiogenesis and tumor growth.29-34 TAMs have been associated with poor prognosis and malignant progression in several malignancies, such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid cancer, and Hodgkin's lymphoma.35-39 Recently, it has also been demonstrated that TAMs play an important role in PNET development, using a transgenic PNET mouse model with diminished TAMs, which developed significantly fewer PNETs compared to the control model.40 They also demonstrated that extent of TAM infiltration in 27 PNET tissue samples could be measured by immunohistochemical staining with the macrophage marker CD68 and that higher CD68 score correlated with higher tumor grade, stage, and liver metastases.40

There is limited data to support recommendations of how NF-PNETs should be monitored after surgery.1 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends initial surveillance at 3-12 months post-resection, then every 6-12 months for the next 10 years for all PNETs (regardless of function).41 Similarly, the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) guidelines provide a minimal consensus recommendation of surveillance every 6 to 12 months, though the authors recommend that this interval“should be adjusted to the type of tumor and the stage of the disease”.2

In randomized, multicenter trials of patients with advanced PNET disease, improved progression-free survival has been demonstrated with use of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus,42 the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib,43 and both streptozocin-based44, 45 and temzolomide-based chemotherapy.46-49 Given the availability of such successful therapies, it is possible that earlier diagnosis of tumor recurrence may improve long-term outcomes. Our objective was therefore to better define risk factors for disease recurrence and parameters to help refine strategies for postoperative surveillance.

Methods

Patients and clinical chart review

A retrospective analysis was carried out for all patients who underwent pancreatic resection at the University of Michigan from June 1995 to November 2012 to identify patients with clinically nonfunctional PNETs. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Clinicopathological variables were reviewed and recorded, including patient demographics, clinical presentation, past medical history, tobacco and alcohol use, family history, neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy, type of resection, post-operative course, histologic findings, and survival.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were obtained from the University of Michigan Department of Pathology. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were retrieved from all 14 patients with recurrent NF-PNET, from both the primary resections and any subsequent operative procedures to resect recurrent or metastatic disease. FFPE blocks were also obtained from 24 patients with non-recurrent disease who had similarly matched clinical and histologic characteristics. Slides (4 μm thick) from the two blocks with the highest tumor content for each sample were used for immunohistochemical staining and evaluated in duplicate and in a blinded manner.

Primary monoclonal mouse antibodies against Ki-67 (1:100 dilution; Dako; Carpinteria, CA) and the monocyte/macrophage marker CD68 (1:200 dilution; Dako; Carpinteria, CA) were used for immunohistochemical analysis. Slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol. The slides were subjected to antigen retrieval via microwaving in Antigen Retrieval Citra Plus Solution (BioGenex; Fremont, CA). Slides were quenched with 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) in phosphate buffered saline. Slides were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Slides incubated with 1% BSA without primary antibody served as negative controls. For detection, slides were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:300 dilution, Vector Labs; Burlingame, CA), detected with VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Reagent (Vector Labs; Burlingame, CA) and Vector DAB substrate (Vector Labs; Burlingame, CA), and counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). CD68 staining was scored blindly from 1-3 for degree of tumor-associated macrophage infiltration as previously described.40 Ki-67 percentage was scored blindly based on 2000-cell counts.50

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using R (www.r-project.org) and GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad; La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was calculated using a Fisher's exact or χ2 test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. A stepwise Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. Disease-free survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used to correlate Ki-67 index to time to recurrence and to compare IHC scores of primary and metastatic/recurrent tumors. Statistical significance was defined as p< 0.05.

Results

A total of 196 PNETs were resected at our institution from June 1995 to November 2012. Of these, 99 patients (50.5%) had NF-PNETs. Two patients had palliative resections for biliary decompression and relief of sinistral hypertension, respectively, and were excluded from further analysis. The remaining 97 patients had intended curative resection. Median follow-up was 2.18 years (range 0.04-14.5 years; the patient last seen at 1 month post-operatively elected to have surveillance elsewhere). Fourteen NF-PNET patients (14.4%) experienced recurrence with a median time to recurrence of 0.61 years and a range from 0.08-10.16 years. Nine patients (64.3%) recurred as a liver metastasis, while three patients (21.4%) recurred in the remaining pancreas. The other three patients recurred in the lung, omentum, and peritoneum.

Of the 14 recurrences, one patient was diagnosed with liver metastasis on MRI less than one month post-operatively during a work-up for superior mesenteric vein thrombosis; this patient likely had occult metastasis at the time of his initial surgery, which had not been appreciated during pre-operative staging. Two patients did not follow the recommended surveillance schedule and were lost to follow-up until diagnosis of their recurrent disease. One patient, who had MEN1, was followed yearly with endoscopic ultrasound after complete resection of his multifocal disease, until a recurrent tumor was diagnosed 10.16 years later. The remaining 10 patients were initially followed at 3- or 6-month intervals with CT and/or octreotide scan, with or without serum chromogranin A. Of the 4 patients followed with 3-month surveillance intervals, all recurrences were diagnosed on surveillance imaging. Of the 6 patients followed with 6-month surveillance intervals, recurrent disease was diagnosed on the first surveillance CT scan in 3 patients and during the intervening intervals in 2 patients; the remaining patient was diagnosed on his 2.5-year surveillance scan.

Seven (50%) of the patients with recurrence underwent surgical re-resection or metastectomy. Of these seven patients, two transferred their care, and two died from multi-organ system failure and acute MI, respectively. Two patients experienced disease recurrence and have remained stable on cisplatin/gemcitabine therapy and sunitinib at 1 and 2.6 years from the time of diagnosis of recurrence. The remaining patient underwent three additional surgeries for recurrent disease in the pancreatic bed and for liver metastasis. She remains disease-free 2 years after her last resection (8 years from her primary resection). Next, clinicopathological characteristics of patients who did and did not experience recurrence after surgical resection were compared for statistical significance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Significant Clinicopathological Factors in NF-PNET Patients With and Without Recurrence After Surgical Resection.

| Factor | Recurrence (n = 14) |

No recurrence (n = 83) |

P-value# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenting symptoms | |||

| Nausea | 4 (29%) | 4 (5%) | 0.0141 |

| Intraoperative EBL (L)* | 1.68±2.18 | 0.55±0.96 | 0.0004 |

| Median | 0.90 | 0.30 | |

| Range | 0.20–8.00 | 0.01–8.00 | |

| Intraoperative transfusions | 0.0019 | ||

| Yes | 3 (21%) | 6 (7%) | |

| No | 8 (57%) | 75 (90%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (21%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Histopathology | |||

| Tumor size (cm, largest dimension)* | 5.44±3.71 | 2.76±2.21 | 0.0021 |

| Median | 4.5 | 2.3 | |

| Range | 0.7-13 | 0-12 | |

| Differentiation | 0.0112 | ||

| Well | 11 (79%) | 82 (96%) | |

| Poor | 3 (21%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Grade | 0.0002 | ||

| Low | 6 (43%) | 69 (83%) | |

| Intermediate | 5 (36%) | 10 (12%) | |

| High | 3 (21%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 3 (4%) | |

| N | 0.0096 | ||

| NX | 1 (7%) | 8 (10%) | |

| N0 | 5 (36%) | 59 (71%) | |

| N1 | 8 (57%) | 18 (19%) | |

| M | 0.0077 | ||

| M0 | 10 (71%) | 80 (96%) | |

| M1 | 4 (29%) | 3 (4%) | |

| AJCC stage | 0.0040 | ||

| IA | 1 (7%) | 29 (34%) | |

| IB | 3 (21%) | 33 (40%) | |

| IIA | 1 (7%) | 2 (2%) | |

| IIB | 5 (36%) | 15 (18%) | |

| III | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| IV | 4 (29%) | 3 (4%) |

Mean ± standard deviation.

P-values were calculated using Fisher's exact or χ2 test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

EBL, estimated blood loss; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Demographics

NF-PNET patients were 50% male and 50% female, with an average age of 55 years (standard deviation [S.D.] = 15 years) in both groups. Ages ranged from 19-76 years old in the recurrence group and 20-85 years old in the non-recurrence group (p = NS). There were no differences in race (p = NS).

Clinical factors

At the time of initial clinical presentation, 29% of patients who subsequently developed recurrent disease complained of persistent nausea, versus 5% in the non-recurrence group (p = 0.01; Table 1). There were otherwise no differences in abdominal pain, diarrhea, jaundice, night sweats, vomiting, or weight loss (all p = NS). There were also no differences in personal or family history of pancreaticobiliary diseases or other malignancies, including diabetes, pancreatitis, MEN1, or VHL (all p = NS). Active and distant history of smoking and heavy alcohol use were equivalent (p = NS).

Pre-operative imaging

All patients were pre-operatively imaged with CT scan and/or MRI of the abdomen/pelvis (93%/43% recurrence vs 98%/29% non-recurrence group; p = NS). Other diagnostic studies included abdominal US (0% vs 5%; p = NS), endoscopic ultrasound (21% vs 55%; p = 0.02), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (7% vs 6%; p = NS), and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (7% vs 4%; p = NS). Based on clinical suspicion, additional staging workup included octreotide scan (50% vs 13%; p = 0.01), CT of the chest (7% vs 22%; p = NS), PET scan (0% vs 5%; p = NS), and bone scan (7% vs 2%; p = NS).

Neoadjuvant factors

There was no difference in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation (all p = NS). Pre-operative chromogranin levels were not significantly different (median 241 recurrence vs 144 ng/mL non-recurrence group; p = NS).

Operative factors

There was no difference in the type of surgical resection performed in the two groups (p = NS). The most common operative procedure was distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy (64% recurrence group, 58% non-recurrence group). Estimated blood loss (EBL) and use of intraoperative transfusions were significantly higher in the recurrence group (p = 0.0004 and 0.0019; Table 1). Average EBL was 1.68 L (range = 0.20-8.0 L; 95% confidence interval [C] = 0.29-3.1 L) in the recurrence group, compared to 0.55 L (range = 0.01-8.0 L; 95% CI = 0.34-0.76 L) in the non-recurrence group.

Post-operative course

There were no differences in the rates of post-operative complications and 30-day readmissions between the two groups (p = NS). The most common complication was grade A pancreatic leak (21% recurrence group, 23% non-recurrence group). One patient underwent reoperation within 30 days for washout of an intraabdominal abscess in the non-recurrence group. There were no differences in the use of octreotide or adjuvant chemotherapy following primary resection between the two groups (p = NS). Three patients in the recurrence group received adjuvant XRT after primary resection for high histologic grade and other invasive features or close margin (≤1 mm). This is compared to two patients in the non-recurrence group, who received adjuvant XRT for close margin and for a high grade lesion with positive lymph nodes (p = 0.02).

Histopathological factors

Tumor locations were equivalent between the two groups (body/tail: 71% recurrence versus 63% non-recurrence; head: 36% recurrence versus 37% non-recurrence; p = NS). Tumor size was significantly larger in the recurrence group, with a median of 4.5 cm in the recurrence group and 2.3 cm in the non-recurrence group (p = 0.002; Table 1), although there was no difference in T stage distribution (p = NS). Poor differentiation and intermediate/high grade (based on mitotic count) were significantly higher in the recurrence group (p = 0.01 and 0.0002; Table 1). Presence of N1, M1, and high American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage were also more prevalent in the recurrence group (p = 0.01, 0.008, and 0.004, respectively; Table 1). Of note, there were 4 patients in the recurrence group (29%) who had Stage IV disease at the time of resection, as compared to 3 patients in the non-recurrence group (4%, p = 0.008).

Survival

There was no difference in mortality related to progression of disease (p = NS). There were a total of four deaths in the recurrence group, but only one of which was directly attributed to disease progression. There were no deaths in the non-recurrence group.

EBL, histologic grade, and stage are the strongest independent risk factors for NF-PNET recurrence by multivariate analysis

A stepwise multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed using the 9 clinicopathological factors that were significantly associated with NF-PNET recurrence by univariate analysis (nausea, intraoperative EBL, intraoperative transfusions, tumor size, differentiation, grade, N stage, M stage, AJCC stage). EBL, histologic grade, and stage were the most significant independent risk factors for recurrence (all p< 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis of Clinicopathological Factors Associated with NF-PNET Recurrence After Surgical Resection.

| Factor | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | 4.00 | 1.88-8.49 | 0.0003 |

| Stage | 1.49 | 1.06-2.12 | 0.022 |

| Intraoperative EBL | 1.57 | 1.18-2.10 | 0.002 |

EBL, estimated blood loss.

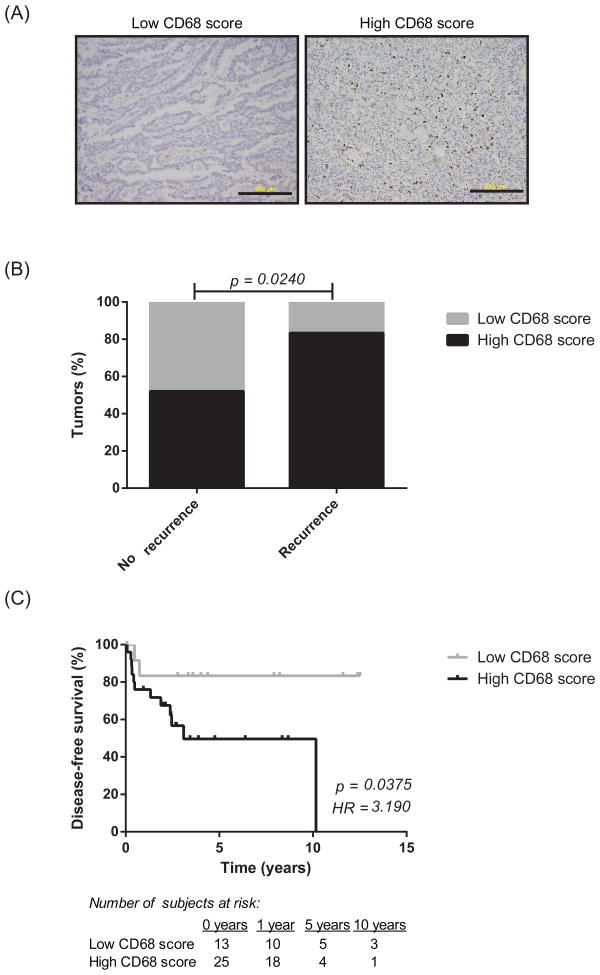

High CD68 score correlates with NF-PNET recurrence

By immunohistochemical staining, high CD68 score (IHC score 2 or 3) as compared to low CD68 score (IHC score 1) correlated with recurrence (p = 0.02; Figure 1A-B). At 12 years, disease-free survival was 0% in patients with high CD68 scores and 83% in patients with low CD68 scores (p = 0.04, hazard ratio = 3.2; Figure 1C). Additional subgroup analysis was performed in those patients who had a low predicted risk of recurrence based on the factors identified in the multivariate analysis. Clinicopathological risk factors for recurrence were defined as EBL >0.76L (based on upper 95% CI in non-recurrence group), intermediate/high grade, and stage III/IV disease. In those patients with fewer than two risk factors, adding CD68 score provided a better prediction of disease recurrence compared to using the combination of EBL, tumor grade, and stage alone (analysis of variance, p = 0.038). In the 7 patients who underwent surgical re-resection or metastectomy for recurrent disease, there were no significant differences in the CD68 scores of the primary and metastatic specimens (p = NS).

Figure 1.

Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD68; scale bar, 200 μm (A). Higher CD68+ macrophage density correlates with cancer recurrence (A) and overall decreased disease-free survival (B). P-values were calculated using χ2 (A) and log-rank tests (B). HR, hazard ratio.

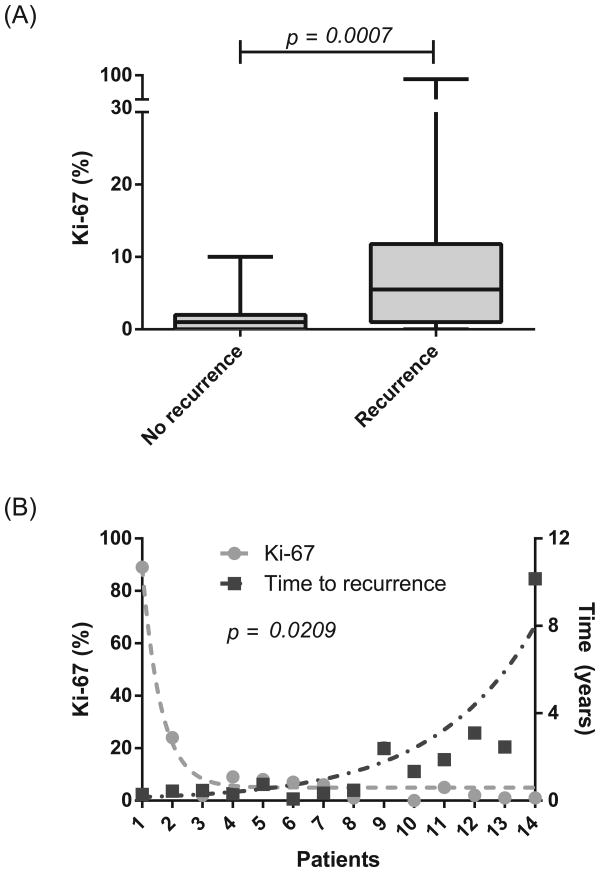

High Ki-67 index correlates with NF-PNET recurrence and early time to recurrence

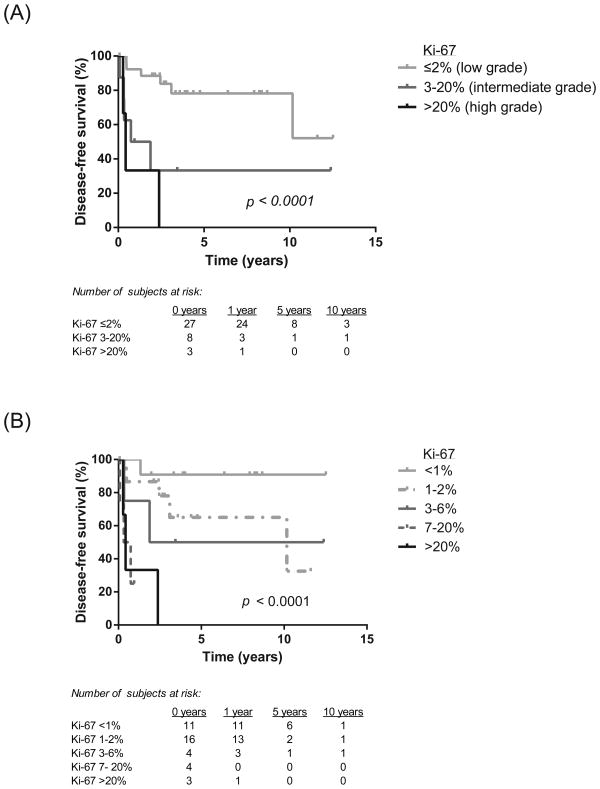

Ki-67 proliferative index was significantly higher in the recurrence group (mean 12.6%, S.D. 23.1%) versus the non-recurrence group (mean 1.75%, S.D. 2.2%), as shown in Figure 2A (p = 0.0007). In the recurrence group, higher Ki-67 index also inversely correlated with time to recurrence (p = 0.02; Figure 2B). Increasing histologic grade (Ki-67 ≤2% low, 3-20% intermediate, >20% high) correlated with worse disease-free survival (Figure 3A). Additional Ki-67 subgroup analysis further stratified survival rates, with a 5-year disease-free survival of 91% in patients with Ki-67 <1% and 0% in patients with Ki-67 >6% (Figure 3B). There was no significant difference in the Ki-67 indices of the primary and metastatic specimens in the patients who underwent surgical re-resection or metastectomy for recurrent disease (p = NS).

Figure 2.

Higher Ki-67 index correlates with cancer recurrence (A) and faster time to recurrence (B). P-values were calculated using Mann-Whitney U (A) and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests (B).

Figure 3.

Higher Ki-67 index correlates with decreased disease-free survival stratified by histologic grade (A) and additional subgroup analysis (B). P-values were calculated using log-rank test.

Discussion

In this large-scale, single institution study, we found a 14.4% (14/97) risk of recurrence after surgical resection of NF-PNETs, with a median time to recurrence of 0.61 years, with 71% (10/14) patients recurring within the first two years after surgery. Of the 6 recurrence patients initially monitored at 6-month intervals, 3 (50%) were diagnosed with recurrence on their first CT scan, and 2 (33%) were diagnosed during the intervening surveillance intervals. Based on these findings, we recommend that patients with a high risk of recurrence be considered for close monitoring with imaging and biochemical surveillance every 3 months for the first 2 years after surgical resection. The intervals may then be lengthened thereafter, based on the patient's clinical risk factors. We hypothesize that earlier identification of recurrent disease would allow for earlier medical and/or surgical intervention and therefore improve patient outcomes, though this strategy will need to be evaluated prospectively in future studies.

We found that significant clinicopathological risk factors for NF-PNET recurrence include higher intraoperative blood loss, high tumor grade, advanced AJCC stage, high CD68 score, and high Ki-67 proliferative index. While advanced histologic grade/Ki-67 index and stage have previously been shown to correlate with poor overall survival,21, 24, 25 this is the first study specifically focusing on the prognostic factors that correlate with disease recurrence. It is important to note that stage was a strong predictor for recurrence, highlighting the significance of following oncologic resection principles for accurate staging. Absolute Ki-67 proliferative index was also a strong predictive factor, independent of the 2% and 20% cut-offs used in histologic grade classification (Figure 3A, B). This is similar to prior studies that showed that a Ki-67 index>5% correlated with poor overall survival.21, 51 In our subgroup analysis, we additionally found that 5-year disease-free survival was 91% in patients with Ki-67 <1% and 0% in patients with Ki-67 >6%, which could allow clinicians the ability to further stratify their NF-PNET patients with uncertain risk of recurrence. In addition, in those patients who had recurrent disease, Ki-67 had a strong inverse relationship with time to recurrence, with low Ki-67 index correlating with later recurrence from the time of primary resection. Therefore, patients with other significant clinical risk factors for recurrence but a low Ki-67 index should still be monitored closely, with clinicians maintaining a high level of suspicion for indolent disease that might recur late in the course of surveillance.

It has previously been reported that high TAM infiltration correlates with PNET development, as well as higher grade, stage, and distant metastasis in a small patient cohort (27 patients).40 This larger study specifically analyzes NF-PNETs and is the first to show a correlation between TAM infiltration and risk of NF-PNET recurrence. CD68 score serves as a useful biomarker for recurrent disease, especially in those patients who otherwise had relatively few clinicopathological risk factors (Table 3). This demonstrates the potential prognostic importance of incorporating CD68 scoring into risk stratification of this disease in patients who otherwise appear at low risk for recurrence.

Table 3.

Summary of Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Factors in NF-PNET Patients with Recurrence After Surgical Resection.

| Patient | Nausea | Diff | Grade | Size (cm) | N | M | Stage | EBL (L) | Transf | CD68 score | Ki67 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Poor | High | 2.5 | N0 | M0 | IB | 0.2 | No | High | 89 |

| 2 | Yes | Poor | High | 8 | N1 | M0 | IIB | 0.5 | No | High | 24 |

| 3 | No | Well | Low | 13 | N0 | M0 | IB | 0.8 | No | Low | 2 |

| 4 | No | Well | Low | 2.5 | N1 | M0 | IIB | 1.8 | No | High | 9 |

| 5 | No | Well | Intermediate | 7.2 | N1 | M1 | IV | 1.5 | Unknown | Low | 8 |

| 6 | No | Well | Intermediate | 7.8 | N1 | M1 | IV | 0.5 | No | High | 7 |

| 7 | Yes | Well | Intermediate | 6 | N0 | M0 | IIA | 0.5 | No | High | 6 |

| 8 | No | Well | Low | 3.2 | N1 | M0 | IIB | 8 | Yes | High | 1 |

| 9 | Yes | Poor | High | 3.5 | N0 | M0 | IB | 1.2 | No | High | 20.2 |

| 10 | Yes | Well | Low | 11.5 | N1 | M0 | IIB | 3.5 | Yes | High | <1 |

| 11 | No | Well | Intermediate | 5.5 | NX | M1 | IV | 0.7 | Unknown | High | 5 |

| 12 | No | Well | Low | 1.5 | N1 | M0 | IIB | 1 | Yes | High | 2 |

| 13 | No | Well | Intermediate | 3.2 | N1 | M1 | IV | 0.7 | Unknown | High | 1 |

| 14 | No | Well | Low | 0.7 | N0 | M0 | IA | 0.7 | No | High | 1 |

Diff, differentiation; EBL, estimated blood loss; Transf, intraoperative blood transfusions.

This is the first, large-scale study analyzing disease recurrence as the clinical endpoint after surgical resection of NF-PNETs, with the specific goal of identifying risk factors for disease recurrence. Our findings of high grade, advanced AJCC stage, and high Ki-67 index as strong predictors for NF-PNET recurrence after surgical resection correlate with previous studies that demonstrated the prognostic value of these factors in predicting overall survival.5, 16, 21, 24 High intraoperative blood loss and high CD68 score as a measurement of TAM infiltration correlating with worse prognosis are new findings and have not been addressed in other reports.

Given the relatively low incidence of NF-PNETs, a major strength of this study is the large number of cases analyzed. Limitations include the single-institution and retrospective design. Utilizing the findings reported in this study, we propose as a next step to validate the significance of the recurrence risk factors identified here in a prospective, multi-center study of surgically resected NF-PNET patients. Clinical and histopathological parameters, including CD68 score, would be prospectively collected, to be correlated with post-operative recurrence and to calculate a scoring algorithm to predict a patient's likelihood and time to disease recurrence. A follow-up study would then be a multi-center, prospective trial randomizing patients to standardized postoperative surveillance versus surveillance intervals/frequency based on their clinically-defined risk to evaluate how such an optimized post-operative surveillance strategy affects patient outcomes.

Current recommendations for post-operative surveillance intervals after NF-PNET resection vary from 6-12 months.2, 41 In our study, we found the initial 6-month interval to be inadequate for early detection of disease recurrence, while the majority of patients who recurred did so within the first 2 years after primary resection. We identified factors associated with recurrence after surgery are high intraoperative blood loss, high grade, advanced AJCC stage, high Ki-67 index, and high CD68 score as a measurement of tumor-associated macrophage infiltration. Based on these findings, we recommend that NF-PNET patients with such risk factors should undergo initial post-operative surveillance every 3 months for the first 2 years after surgical resection.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grant 5T32CA009672-22 (I.H.W.) and the Rogel Family Pancreatic Cancer Fund.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any financial conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Minter RM, Simeone DM. Contemporary management of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:435–46. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falconi M, Bartsch DK, Eriksson B, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system: well-differentiated pancreatic non-functioning tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:120–34. doi: 10.1159/000335587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1727–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilimoria KY, Tomlinson JS, Merkow RP, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment trends of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: analysis of 9,821 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1460–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0263-3. discussion 1467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gullo L, Migliori M, Falconi M, et al. Nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumors: a multicenter clinical study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2435–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vagefi PA, Razo O, Deshpande V, et al. Evolving patterns in the detection and outcomes of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience from 1977 to 2005. Arch Surg. 2007;142:347–54. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.4.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconi M, Plockinger U, Kwekkeboom DJ, et al. Well-differentiated pancreatic nonfunctioning tumors/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:196–211. doi: 10.1159/000098012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panzuto F, Nasoni S, Falconi M, et al. Prognostic factors and survival in endocrine tumor patients: comparison between gastrointestinal and pancreatic localization. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:1083–92. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan GQ, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, et al. Surgical experience with pancreatic and peripancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Review of 125 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:473–82. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(98)80039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madeira I, Terris B, Voss M, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with endocrine tumours of the duodenopancreatic area. Gut. 1998;43:422–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.3.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White TJ, Edney JA, Thompson JS, et al. Is there a prognostic difference between functional and nonfunctional islet cell tumors? Am J Surg. 1994;168:627–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80134-5. discussion 629-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hochwald SN, Zee S, Conlon KC, et al. Prognostic factors in pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: an analysis of 136 cases with a proposal for low-grade and intermediate-grade groups. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2633–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrone CR, Tang LH, Tomlinson J, et al. Determining prognosis in patients with pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: can the WHO classification system be simplified? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5609–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekeblad S, Skogseid B, Dunder K, et al. Prognostic factors and survival in 324 patients with pancreatic endocrine tumor treated at a single institution. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7798–803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bettini R, Partelli S, Boninsegna L, et al. Tumor size correlates with malignancy in nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumor. Surgery. 2011;150:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solorzano CC, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Nonfunctioning islet cell carcinoma of the pancreas: survival results in a contemporary series of 163 patients. Surgery. 2001;130:1078–85. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.118367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haynes AB, Deshpande V, Ingkakul T, et al. Implications of incidentally discovered, nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumors: short-term and long-term patient outcomes. Arch Surg. 2011;146:534–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.House MG, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Differences in survival for patients with resectable versus unresectable metastases from pancreatic islet cell cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Touzios JG, Kiely JM, Pitt SC, et al. Neuroendocrine hepatic metastases: does aggressive management improve survival? Ann Surg. 2005;241:776–83. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161981.58631.ab. discussion 783-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bettini R, Boninsegna L, Mantovani W, et al. Prognostic factors at diagnosis and value of WHO classification in a mono-institutional series of 180 non-functioning pancreatic endocrine tumours. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:903–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamberlain RS, Canes D, Brown KT, et al. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432–45. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, et al. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010;39:735–52. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franko J, Feng W, Yip L, et al. Non-functional neuroendocrine carcinoma of the pancreas: incidence, tumor biology, and outcomes in 2,158 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:541–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Rosa S, Sessa F, Capella C, et al. Prognostic criteria in nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumours. Virchows Arch. 1996;429:323–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00198436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011;331:1199–203. doi: 10.1126/science.1200609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbo V, Beghelli S, Bersani S, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumours: mutational and immunohistochemical survey of protein kinases reveals alterations in targetable kinases in cancer cell lines and rare primaries. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:127–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Missiaglia E, Dalai I, Barbi S, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: expression profiling evidences a role for AKT-mTOR pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:245–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol. 2002;196:254–65. doi: 10.1002/path.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JS, Landers RJ, Underwood JC, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by macrophages is up-regulated in poorly vascularized areas of breast carcinomas. J Pathol. 2000;192:150–8. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH687>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Post M, Volk R, et al. PR39, a peptide regulator of angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:49–55. doi: 10.1038/71527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leek RD, Landers RJ, Harris AL, et al. Necrosis correlates with high vascular density and focal macrophage infiltration in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:991–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JS, Lee JA, Underwood JC, et al. Macrophage responses to hypoxia: relevance to disease mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:889–900. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner L, Scotton C, Negus R, et al. Hypoxia inhibits macrophage migration. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2280–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2280::AID-IMMU2280>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006;66:605–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryder M, Ghossein RA, Ricarte-Filho JC, et al. Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:1069–74. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson BD, Sica GL, Liu YF, et al. Tumor microenvironment of metastasis in human breast carcinoma: a potential prognostic marker linked to hematogenous dissemination. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2433–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Research. 2006;66:605–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pyonteck SM, Gadea BB, Wang HW, et al. Deficiency of the macrophage growth factor CSF-1 disrupts pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor development. Oncogene. 2012;31:1459–67. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulke MH, Benson AB, 3rd, Bergsland E, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:724–64. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:514–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:501–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, et al. Streptozocin-doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:519–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kouvaraki MA, Ajani JA, Hoff P, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4762–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ekeblad S, Sundin A, Janson ET, et al. Temozolomide as monotherapy is effective in treatment of advanced malignant neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2986–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kulke MH, Stuart K, Enzinger PC, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:401–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kulke MH, Hornick JL, Frauenhoffer C, et al. O6-methylguanine DNA methyl transferase deficiency and response to temozolomide-based therapy in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:338–45. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strosberg JR, Fine RL, Choi J, et al. First-line chemotherapy with capecitabine and temozolomide in patients with metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. Cancer. 2011;117:268–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rindi G, Kloppel G, Alhman H, et al. TNM staging of foregut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelosi G, Bresaola E, Bogina G, et al. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas: Ki-67 immunoreactivity on paraffin sections is an independent predictor for malignancy: a comparative study with proliferating-cell nuclear antigen and progesterone receptor protein immunostaining, mitotic index, and other clinicopathologic variables. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1124–34. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]