Abstract

Proteasome-mediated degradation is a common mechanism by which cells renew their intracellular proteins and maintain protein homeostasis. In this process, the E3 ubiquitin ligases are responsible for targeting specific substrates (proteins) for ubiquitin-mediated degradation. However, in cancer cells, the stability and the balance between oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins are disturbed in part due to deregulated proteasome-mediated degradation. This ultimately leads to either stabilization of oncoprotein(s) or increased degradation of tumor suppressor(s), contributing to tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Therefore, E3 ubiquitin ligases including the SCF types of ubiquitin ligases have recently evolved as promising therapeutic targets for the development of novel anti-cancer drugs. In this review, we highlighted the critical components along the ubiquitin pathway including E1, E2, various E3 enzymes and DUBs that could serve as potential drug targets and also described the available bioactive compounds that target the ubiquitin pathway to control various cancers.

Keywords: Cancer, SCF, Ubiquitin ligase, Deubiquitinating enzyme, Drug Targets

1. Introduction

1.1. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the E1-E2-E3 ubiquitination enzymatic cascade

The abundance of proteins within a cell should be tightly regulated according to the cellular needs or physiological demand [1]. Dysregulated pool of proteins may lead to various types of disorders including human cancers [2]. It is known that both the rate of synthesis and the speed of destruction determine the intracellular level of a given protein, and the latter mechanism is commonly referred as proteolysis [3]. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that there are two major proteolytic pathways, namely proteasome-mediated degradation and lysosomal-mediated proteolysis, which are conserved from yeast to human [4]. Studies have also suggested that eukaryotic cells mainly utilize the two regulatory mechanisms to clear the damaged or unwanted proteins to prevent constant activation of specific molecular signaling pathways that may cause diseases such as cancer [5].

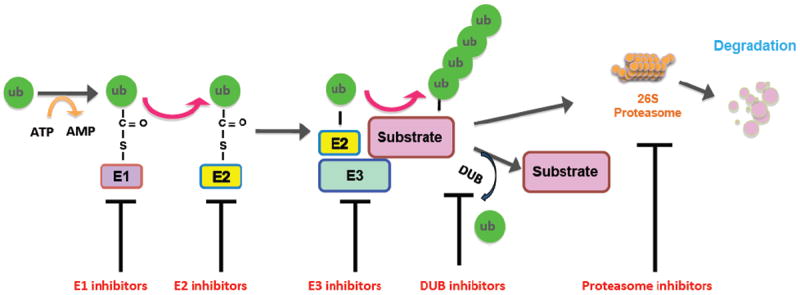

It is well accepted that proteasome-mediated proteolysis consists of two main steps. The first step is protein labeling for destruction, and the second step is protein degradation by the 26S proteasome [6]. Specifically, the first step is further divided into three coordinated strides: activation of the ubiquitin molecule by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), transfer of ubiquitin by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and subsequently the attachment of ubiquitin moieties to the substrate protein by the ubiquitin ligase (E3) [7]. It has been well documented that ubiquitin is a 76-amino-acid protein that is highly conserved among eukaryotic organisms and present in all type of cells [8]. Mechanistically, ubiquitin molecules are activated by the E1 enzyme via associating to the cysteine residues of the E1 enzyme through a thioester bond in an ATP-dependent manner. Then, the activated ubiquitin molecule is transferred to a cysteine residue of the E2 enzyme, which is subsequently recruited into the E3 ligases. Finally, the E3 complex binds substrate proteins with a recognizable subunit, bridging the ubiquitin-charged, active forms of E2 and the substrate protein that is targeted to be degraded and facilitating the attachment of ubiquitins to targeted proteins [9] (Figure 1). Hence, E3 ligases attract more research attention than E1 and E2 enzymes in part due to the high variability of their components that play a significant role in determining the substrate specificity [10].

Figure 1.

Proteasome-mediated proteolysis is achieved by a series of enzymatic steps: activation of the ubiquitin molecule by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), transfer of ubiquitin by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and subsequently the attachment of ubiquitin moieties to the substrate protein by the ubiquitin ligase (E3), a process that could be antagonized by DUB-mediated deuibuiquitination. Afterwards, the ubiquitinated proteins are degraded by the 26S proteasome. Many compounds or inhibitors have been developed to target essential components in the ubiquitin proteasome system including E1, E2, E3 ligases, DUBs and the proteasome, which influence proteasome-mediated degradation system, therefore affects the abundance of certain oncoprotein(s) or tumor suppressor protein(s) to achieve effective anti-cancer effects.

1.2. The classification of E3 ubiquitin ligases

E3 ligases are structurally categorized into three major types: U-box domain, really interesting new gene (RING), and homologous to E6-associated protein C-terminus (HECT) [11]. Interestingly, HECT type E3 ligases receive ubiquitin from E2 enzyme, and directly link ubiquitin molecules to the lysine residue of target proteins independent of the E2 enzyme. Unlike HECT type, U-box and RING type E3 ligases largely function as scaffolding proteins and provide docking sites for the ubiquitin-charged E2 and substrate proteins. RING type E3 ligase is characterized as a subunit containing RING domain for recruiting E2 enzyme. Notably, RING E3 ligases are further classified into single-molecular RING containing E3 ligases or multi-subunit E3 ligase complexes including various Cullin-containing E3 ligase complexes such as Skp1/Cul1/F-box protein complex (SCF), Cullin 2/Elongin B/C/VHL, Cullin 3/BTB, Cullin 4A/DDB1/DCAF, Cullin 4B/DDB1/DCAF, Cullin 5/SOCS, Cullin 7/FBXW8, as well as the Cullin-related anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome complex (APC/C) [12-17].

There is growing evidence that SCF ubiquitin ligases plays a crucial role in the development and progression of human cancer, suggesting that SCF ubiquitin ligases could be promising therapeutic targets for designing anti-tumor drugs. Therefore, in this review, we mainly focused on the mechanisms of protein degradation, and the specific ligases involved in the ubiquitin-mediated degradation, as well as how dysfunction of E3 ligases including SCF ubiquitin ligases leads to cancer development, and finally pharmacological intervention of proteasome in cancer treatment.

2. Small molecules target the ubiquitin-proteasome system

A growing body of literature implicates that some compounds target general components in the ubiquitin proteasome system including E1, E2, E3 and proteasome, which influence proteasome-mediated degradation system [7]. It is noteworthy that although numerous efforts have been made to develop potent inhibitors for E1, E2 and proteasome, lack of specificity impeded to use these types of compounds in their clinical applications. Generally, these inhibitors target various components of the ubiquitin proteasome system, thereby affecting the pool of virtually all physiologically essential proteins along with the targeted protein substrates. This leads to the elevation of essential as well as non-essential proteins in cells that could cause severe side-effect due to the off-target effects. In contrast, E3 ligases possess relatively high selectivity to substrate proteins, and are believed to be a more promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment with less off-target effects.

2.1. Targeting the E1 enzyme

E1 enzyme is indispensable for proteasome-based degradation process by activating ubiquitin molecules, demonstrating that E1 enzyme could be a highly effective pharmacological target for inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Several compounds have been reported to targeting E1 enzyme (Table 1). The first E1-targeting compound, panepophenanthrin, was discovered in the fermented broth of a mushroom strain in 2002 [18]. Although panepophenanthrin inhibited the binding of ubiquitin to E1, this compound did not inhibit cell growth, suggesting that further investigation is required to explore its cellular effects [18]. Subsequently, panepophenanthrin was synthesized in its racemic form [19-21] and new cell-permeable E1 inhibitors, RKTS-80, -81, and -82 were developed [22]. Furthermore, Himeic acid A, a metabolite isolated from a marine fungus, also exhibited an inhibitory effect on E1 catalytic activity [23]. In addition, Largazole, known as a putative histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, has also been reported to disrupt the formation of ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, indicating that largazole could be an E1-targeting agent as well [24]. In line with this notion, it has been reported that Largazole inhibited the proliferation and clonogenic activity in lung cancer cells [25]. Notably, the most potent E1 inhibitor, hyrtioreticulins A, was recently identified from sponge along with hyrtioreticulins B, which also possessed inhibitory effect [26]. Interestingly, both largazole and hyrtioreticulins are derived from marine organisms. It is to be noted that an adenosine sulfamate analogue is known to inhibit the activity of human E1 protein. In this process, this compound forms an adduct with ubiquitin molecules, which strongly binds at the active site of the E1 enzyme, and eventually blocks the completion of the ubiquitin activation process [27].

Table 1.

The list of compounds targeting E1 enzymes

| Compound | Target and function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Panepophenanthrin | From fermented broth of a mushroom strain; inhibits the binding of ubiquitin to E1; does not inhibit cell growth | [18] |

| [19-21] | ||

| RKTS-80, -81, and -82 | Cell-permeable E1 inhibitors | [22] |

| Himeic acid A | Froms a marine fungus; an inhibitory effect on E1 catalytic activity | [23] |

| Largazole | Histone deacetylase inhibitor; disrupts the formation of ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate | [24] |

| Hyrtioreticulins A, | From the marine sponge Hyrtios reticulates; inhibits E1 activity | [26] |

| Adenosine sulfamate analogue | Forms an adduct with ubiquitin molecules, binds at the active site of the E1 enzyme, and blocks the completion of the ubiquitin activation process | [27] |

| PYR-41 | Blocks the ubiquitination of TRAF6 and prevents the proteasomal degradation of IκBα and p53 | [28] |

| E1 inhibitors | Block E1-dependent ATP-PP exchange activity, leading to the loss of E1 thioester and inhibition of the E1-E2 transthiolation | [27] |

| MLN4924 | A blocking agent for Cullin neddylation via suppressing the Nedd8-activating E1 enzyme | [32, 33] |

| Deoxyvasicinone derivative | Inhibit NAE activity through blocking the ATP-binding domain | [34] |

Recently, Yang et al reported a new cell permeable inhibitor of E1, PYR-41 [28]. This group found that PYR-41 blocked the ubiquitination of TRAF6 and prevented the proteasomal degradation of IκBα and p53 [28]. More importantly, PYR-41 killed transformed p53-expressing cells, demonstrating that PYR-41 is an effective E1 inhibitor for treatments of human cancers [28]. More recently, Chen et al. reported several additional E1 inhibitors [27]. Specifically, these E1 inhibitors blocked E1-dependent ATP-PP exchange activity, leading to the loss of E1 thioester and subsequent inhibition of the E1-E2 transthiolation [27]. However, further in-depth investigations are required to fully validate their biological effects in treating human cancer cells, and whether these identified E1 inhibitors could specifically target a subset of cancer cells, but sparing normal somatic cells, for induced cell death.

In addition, it has been known that Cullins are indispensable components functioning as scaffold molecules in an multi-subunit E3 ligase complex mentioned above [29]. More importantly, the attachment of an ubiquitin-like molecule Nedd8 to Cullins, a process also referred as neddylation, is a prerequisite for achieving robust catalytic activity of an E3 ligase [30, 31]. This unique modification provides an alternative strategy to target proteasome-mediated degradation. To this end, MLN4924, a potent and selective inhibitor, was identified as a blocking agent for Cullin neddylation via suppressing the Nedd8-activating E1 enzyme (NAE), which eventually attenuates the function of the various Culllin-containing E3 ligases to exert its anti-tumor activities [32, 33]. Furthermore, natural compounds also were reported to inhibit the function of NAE. For example, a dipeptide-conjugated deoxyvasicinone derivative was recently found to inhibit NAE activity through blocking the ATP-binding domain [34], while its biological effects in anti-cancer treatments require addition studies.

2.2. Targeting the E2 enzyme

Studies have identified nearly forty E2 enzymes, indicating that inhibiting E2 enzymes could lead to blocking the degradation of many substrates. A line of evidence has shown that E2 inhibitors suppress E2 catalytic activity (Table 2). For example, inhibition of the E2 enzyme Cdc34 by its inhibitor, CC0651, suppressed cell proliferation and led to accumulation of Skp2 substrate p27 in human cancer cell lines [35, 36]. Leucettamol A, a cyclic peptide isolated from a marine sponge, has been shown to inhibit the function of a heterodimeric E2 enzyme, UBC13-UEV1A complex, by interrupting the interaction between UBC13 and UEV1A [37]. In addition, Manadosterols A and B, which are derived from another species of sponge, are recently identified as the UBC13-UEV1A complex inhibitors [38]. It is worth noting that the UBC13-UEV1A E2 protein is responsible for the attachment of additional ubiquitin molecules to the K63, instead of the K48 residue of ubiquitin, to form a K63-linkage poly-ubiquitination chain on a substrate protein [39]. This specific linkage of poly-ubiquitination modification is known to regulate the NF-κB signaling, rather than acting as a destruction mark, such as the well-studied K48-linkage or K11-linkage poly-ubiquitination that are largely targeting the modified proteins for degradation [40].

Table 2.

The list of compounds targeting E2 enzymes

| Compound | Target and function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CC0651 | E2 enzyme Cdc34 inhibitor, suppresses cell proliferation and leads to accumulation of Skp2 substrate p27 | [35, 36] |

| Leucettamol A | A cyclic peptide isolated from a marine sponge; inhibits the function of a heterodimeric E2 enzyme, UBC13-UEV1A complex, by interrupting the interaction between UBC13 and UEV1A | [37] |

| Manadosterols A and B | Derived from sponge, the UBC13-UEV1A complex inhibitors | [38] |

2.3. Targeting E3 ligases

Since E3 ligases determine the target specificity for ubiquitination, inhibiting a single E3 ligase could be a better approach to treat human cancers with less side effects. Several E3 ligases have been extensively studied, including Fbw7 (F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7), Skp2, MDM2, and β-TRCP [6]. It is worth mentioning that Skp2 and MDM2 are largely functioning as oncoproteins, whereas Fbw7 is a bona fide tumor suppressor. Interestingly, β-TRCP could exert its oncogenic or anti-tumor activity in a cellular- or context- dependent manner [6]. Therefore, targeting these E3 ligases is believed to specifically stabilize a subset of tumor suppressors or promote the degradation of a subset of oncoproteins without affecting the function of other proteinss that are important for normal cellular physiology. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the function of these important E3 ligases and the potential usage of their potential inhibitors in cancer treatments (Table 3).

Table 3.

The list of compounds targeting E3 ligases

| Target | Compound | Target and function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fbw7 | Oridonin | A diterpenoid compound extracted from medicinal plants, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells | [71] |

| Fbw7 | Genistein | From soybean, upregulates Fbw7 expression, inhibits cell growth and invasion in pancreatic cancer cells | [72] |

| Fbw7 | SCF-12 | A biplanar dicarboxylic acid compound, distorts its substrate binding pocket and impede recognition of phosphodegron on substrates | [73] |

| Skp2 | Compound CpdA | Increasing p27 levels in cancer cells via preventing it from recruitment to Skp2 ligase complex | [88] |

| Skp2 | SMIP0004 | Developed through a high-throughput screening to inhibit Skp2 | [90] |

| Skp2 | Compound 25 (SZL-P1-41) | Inhibits Skp2 E3 ligase activity | [89] |

| Skp2 | Curcumin, quercetin, lycopene, silibinin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, Vitamin D3 | Natural agents, inhibit the expression of Skp2 in human cancers | [91-94] |

| β-TrCP | Erioflorin | From Eriophyllum lanatum, inhibits the interaction between β-TrCP and its substrates. | [114] |

| Fbxl3 | KL001 | Binds to pocket in CRY substrates and blocks Fbxl3 binding | [115] |

| Fbxo3 | BC-1215 | Competitively inhibits the substrate binding to Fbxo3 | [116] |

| Cdc20 | Pro-TAME | Binds to the APC and prevents its activation by Cdc20 and Cdh1 | [126, 127] |

| Cdc20 | Apcin | Binds to Cdc20 and subsequently inhibits the ubiquitylation of D-box-containing substrates | [128] |

| Cdc20 | Tosyl-l-arginine methyl ester | Blocks the APC/C-Cdc20 and APC/C-Cdh1 interaction. | [128] |

| Cdc20 | NAHA | A novel hydroxamic acid-derivative, down-regulates the expression of Cdc20 in breast cancer cells | [129] |

| Cdc20 | Medicinal mushroom blend | Suppresses Cdc20 expression in breast cancer cells | [130] |

| Cdc20 | Ganodermanontriol (GDNT) | A ganoderma alcohol from medicinal mushroom, inhibits Cdc20 expression in breast cancer cells | [131] |

| Mdm2 | Nutlin | The first selective small molecule that specifically targets MDM2-p53 interaction | [135] |

| Mdm2 | RITA, HLI98, MITA, NSC 333003, a nutlin analog L2, MBNA, tenovin-6, MI-63, MI-219, and others | These compounds target Mdm2. | [137-169] |

2.3.1. Fbw7

Fbw7, a well known tumor suppressor, recognizes and ubiquitinates multiple important oncoproteins including c-Myc [41-43], c-Jun [44, 45], Cyclin E [46-48], mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) [49], Mcl-1 (Myeloid cell leukemia-1) [50, 51], HIF-1α (Hypoxia inducible factor-1α) [52, 53], KLF5 (Kruppel-like factor 5) [54, 55], MED13 (Mediator 13) [56], KLF2 [57], NF-κB2 (Nuclear factor-κB2) [58, 59], and G-CSFR (Granulocyte colony stimulating factor receptor) [60] and Notch-1 [61-63]. Given its critical role in tumor suppression, Fbw7 expression and activities are tightly controlled. To this end, many Fbw7 upstream genes including p53, Pin1 (Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1), C/EBP-δ (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-δ), and Hes-5 (Hairy and Enhancer-of-split homologues 5) have been identified to govern the expression or the cellular activities of Fbw7 [64-66]. Increasing evidence has also revealed that microRNAs (miRNAs) including miR-27a, miR-25 and miR-223 could also control Fbw7 expression [67-70]. More importantly, there is ample evidence to support the notion that Fbw7 is frequently depleted or mutated in a variety of human cancers. Therefore, restoring Fbw7 function via regulating its upstream factors could be a promising approach for treating cancers.

The Fbw7’s selectivity and specificity towards degradation of oncoprotein ensures it as a promising target for anti-cancer therapies. Oridonin, a diterpenoid compound extracted from medicinal plants, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in K562 myeloid leukemia cells by decreasing the intracellular level of c-Myc protein [71]. Studies showed that the reduction in c-Myc abundance by oridonin is in part due to its effects on the elevation of Fbw7 abundance. In addition, other Fbw7 substrates including Cyclin E and mTOR are downregulated as a result of oridonin treatment indicating its possible direct effects on Fbw7 [71]. In addition, genistein was reported to upregulate Fbw7 expression due to down-regulation of miR-223, leading to the inhibition of cell growth and invasion in pancreatic cancer cells [72]. The homolog of Fbw7 in yeast, Cdc4, has also been recently reported to be a druggable target. SCF-12, a biplanar dicarboxylic acid compound, has been shown to distort its substrate binding pocket and impedes recognition of phosphodegron on substrates [73]. However, it should be bearing in minds that these Fbw7-inducing agents should be only given to patients with WT-Fbw7 genetic status but not those with deleted or mutated Fbw7 genetic backgrounds.

2.3.2. Skp2

Skp2 (S-phase kinase associated protein 2) plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of human cancers [74]. It has been found that Skp2 targets and degrades its ubiquitination targets such as p21 [75], p27 [76], p57 [77], E-cadherin [78], and FOXO1 [79], many of which are well characterized tumor suppressors, to exert its oncogenic functions. For example, Skp2 E3 ligase binds and ubiquitinates cell cycle negative regulator p27, contributing to the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells [80]. Some studies have demonstrated that Skp2 was critically involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis in a variety of human malignancies [81]. Consistently, overexpression of Skp2 was observed in a range of human cancers including primary breast tumors [82, 83], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [84] and prostate cancer [74]. Moreover, overexpression of Skp2 is associated with poor prognosis in various human cancers, advocating a strong clinical association of Skp2 elevation with cancer progress [85].

Since Skp2 could be a dream target for cancer therapy, targeting Skp2 could bring benefits for the treatment of various human cancers with aberrant activation or overexpression of Skp2 [86]. To this end, selective small molecule inhibitors for Skp2 have already been developed which promote the accumulation of p27 by targeting their binding interface, thereby exerting anti-cancer activity [87]. Specifically, the compound CpdA, is capable of increasing p27 levels in cancer cells through preventing it from recruitment to Skp2 ligase complex [88]. Moreover, Skp2 inhibitors, namely, SMIP0004, and Compound 25 (also known as SZL-P1-41) have been developed through a high-throughput screening [89, 90]. Consistently, SMIP0004 was reported to induce G1 delay, inhibit colony formation and cell proliferation in prostate cancer cells in part due to its ability to downregulate Skp2 abundance [90]. Notably, compound 25 selectively inhibited Skp2 E3 ligase activity and subsequently exhibited its anti-tumor activities and cooperated with various chemotherapeutic drugs to suppress tumor growth [89]. Furthermore, multiple natural compounds such as curcumin, quercetin, lycopene, silibinin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, and Vitamin D3 have also been reported to inhibit the expression of Skp2 and subsequently exert their anti-tumor activities [91-94]. However, further in vitro cell culture as well as in vivo mice modeling studies should be further pursued to validate the anti-tumor effects of these above mentioned Skp2 inhibitors.

2.3.3. β-TRCP

A number of evidence has demonstrated that β-TRCP could exert its oncogenic or tumor suppressor activities, which is tissue- or cellular context-dependent manner. The possible reason of β-TRCP’s dual roles could be due to its multiple specific substrates such as Cdc25a [95, 96], β-catenin [97], caspase-3 [98], Emi1 [99, 100], Mdm2 [101], IκB [102], PDCD4 [103], Snail [104], MTSS1 [105] and Wee1 [106]. In line with this concept, loss of β-TRCP and overexpression of β-TRCP have been observed in a variety of human cancers [107]. For example, aberrant upregulation of β-TRCP has been found in pancreatic cancer [108], gastric cancer [109], colon cancer [110] and breast cancer [111, 112]. Therefore, targeting β-TRCP may be a therapeutic strategy in defined subset of human tumors. Erioflorin, a small molecule isolated from Eriophyllum lanatum, has been recently demonstrated to stabilize the tumor suppressor PDCD4, a well-characterized β-TRCP substrate [113], via disrupting its proteasome-mediated degradation [114]. Intriguingly, the target of Erioflorin is not general components of ubiquitin proteasome system, but the specific E3 ligase SCFβ-TRCP, which is responsible for Pdcd4 ploy-ubiquitination. Specifically, Erioflorin inhibits the interaction between β-TRCP and its substrates including PDCD4. Interestingly, Erioflorin had no influence on other E3 ligase activity, such as Skp2 and von Hippel Lindau (VHL). This is the first reported compound that specifically suppresses the function of β-TRCP E3 ligase, while its effects on other β-TRCP substrates remain largely undefined. However, β-TRCP may not serve as an effective anti-cancer drug target largely because β-TRCP regulates the degradation of both tumor suppressors and oncoproteins in a cellular or context dependent manner [80, 107], therefore its anti-tumor clinical effects should be interpreted with caution.

2.3.4. Other SCF type of E3 ligases

There are some critical emerging evidence demonstrates that multiple compounds target other E3 ligases such as Fbxl3 [115] and Fbxo3 [116]. It has been shown that Fbxl3 ubiquitin ligase targets and promotes cryptochrome (CRY) ubiquitination and degradation to regulate the mammalian circadian clock [117]. To this end, KL001 was developed to bind to pocket in CRY substrates and block Fbxl3 binding, which could have a therapeutic potential in the future [115]. Additionally, BC-1215 was reported to competitively inhibit the substrate binding to Fbxo3 [116], while it cellular effects require further validation.

2.3.5. Anaphase Promoting Complex

The APC governs the cell cycle progression through forming two E3 ubiquitin ligase sub-complexes, APCCdc20 and APCCdh1. It has been accepted that Cdh1 is a tumor suppressor, while Cdc20 is an oncoprotein [118]. Studies have shown that Cdc20 targets multiple substrates with the Destruction Box (D-box) motif including Securin [119], Cyclin B1 [120, 121], Cyclin A [122, 123], p21 [124], and Mcl-1 [125] for degradation to regulate cell cycle progression. In support of the oncogenic role of Cdc20, overexpression of Cdc20 has been observed in a variety of human cancers, suggesting that targeting Cdc20 could be useful for the treatment of human malignancies [118]. To this end, multiple groups have reported several inhibitors that inhibit the Cdc20 expression. Unfortunately, specific Cdc20 inhibitors have not been discovered so far.

One elegant study by the King group has demonstrated that a small molecule inhibitor of APC, TAME (tosyl-L-arginine methyl ester), binds to the APC core complex and prevents its activation by either Cdc20 or Cdh1 [126]. Moreover, this group synthesized a pro-TAME, which empowered the otherwise non-penetrating TAME to enter cells and induced mitotic arrest [126, 127]. Recently, they further developed a new inhibitor apcin (in short for APC inhibitor), which binds to Cdc20 relatively stronger than Cdh1, and subsequently inhibits the ubiquitination of D-box-containing substrates such as cyclin B [128]. Importantly, combination of tosyl-l-arginine methyl ester with apcin treatment amplified their effects in blocking mitotic exit [128]. In addition, NAHA, a novel hydroxamic acid-derivative, has also been reported to down-regulate the expression of Cdc20 in breast cancer cells [129]. Notably, a novel medicinal mushroom blend was found to suppress the expression of Cdc20 in breast cancer cells but its effective compound and underlying molecular mechanisms remain largely undefined [130]. Furthermore, ganodermanontriol (GDNT), a ganoderma alcohol from medicinal mushroom, was identified to inhibit Cdc20 expression in breast cancer cells [131]. Since Cdc20 plays an important role in tumorigenesis, specific Cdc20 inhibitors, rather than pan-APC inhibitors, could be potentially effective anti-cancer agents.

2.3.6. MDM2

Unlike β-TRCP, murine double minute 2 (MDM2) is well established as the principal negative regulator for p53 stability, and hence acts as an oncoprotein to promote cancer development [132]. Its relatively high selectivity to p53 allows MDM2 to be considered as an ideal target for drug screening and designing specific drugs that affect MDM2 levels through proteasome-mediated degradation pathway in cancer cells [133]. In fact, a number of MDM2-targeting compounds have been identified or designed, which accounts for the majority of the current E3-liagse-targeting molecules [134]. Nutlin is the first selective small molecule that specifically targets MDM2-p53 interaction [135]. Crystal structure analysis revealed that Nutlin interacts with a region in p53, which MDM2 also utilizes to bind with the p53 protein [136]. Other MDM2-specific compounds include RITA [137, 138], HLI98 [139], pyrrolidone derivatives [140], Isoindolinone-based compound [141-143], MITA [144], NSC 333003 [145], a nutlin analog L2 [146], methylbenzo-naphthyridin-5-amine (MBNA) [147], tenovin-6 [148], MI-63 [149], MI-219 [150], pyrrolopyrimidine-based α-helix mimetic [151], etoposide [152], 1,4-diazepines [153], Helical beta-peptide inhibitor [154], thio-benzodiazepines [155], imidazoline derivatives [156, 157], pyrrolidone derivatives, dehydroaltenusin [158], Lissoclinidine B [159], Gambogic acid [160, 161], Chlorofusin [162, 163], Hexylitaconic acid [164, 165], sempervirine [161], Parthenolide [166], berberine [167], Hoiamide D [168] and 25-OCH(3)-PPD [169].

Furthermore, other p53-recognizing E3 ligases, such as Ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A (UBE3A) and MDM4, also serve as promising targets for anti-cancer therapies. For instance, aloe-emodin elicits apoptosis in Huh-7 hepatoma cells, at least partially by downregulating UBE3A [170]. Natural product-like macrocyclic N-methyl-peptides are also identified as UBE3A-specific inhibitors by screening on a ribosome-expressed de novo library [171]. A small molecule SJ-172550 is reported to inhibit the interaction between MDM4 and p53 [172], while its anti-cancer effects warrant further in-depth studies.

2.3.7. NEDD4

The neuronally expressed developmentally downregulated 4 (NEDD4) belongs to HECT-type E3s [173]. As an E3 ligase, NEDD4 has been demonstrated to play an oncogenic role in facilitating human cancer progression [174]. Physiologically, NEDD4 has been found to target numerous substrates including ENaC (epithelial sodium channel) [175], Notch [176, 177], pAKT [178], IGF-1R (insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor) [179], VEGF-R2 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2) [180], PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) [181] and MDM2 [182] to exert its biological functions. Amounting evidence has revealed that NEDD4 is frequently overexpressed in a range of human cancers including colorectal cancer [183], breast cancer [184], NSCLC [185], gastric cancer [186], prostate and bladder cancers [187]. These findings suggest that NEDD4 is a legitimate target for designing new drugs to treat human malignancies. Surprisingly, NEDD4 inhibitors have not been discovered so far. Therefore, it is required to develop NEDD4 inhibitors to suppress the expression of NEDD4 and achieve the better treatment for cancer patients.

2.4. Targeting proteasome activity

In 1993, peptidyl aldehydes were found to inhibit proteasome activity [188]. Similar to E1 and E2 enzyme inhibitors, a number of natural products have also been found that possessed the inhibitory activities on the proteasome (Table 4). Among these compounds, Bortezomib is the first drug approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat multiple myeloma (MM) and mantle cell lymphoma [189, 190]. In spite of anti-tumor activity, Bortezomib was found to be toxic to normal cells due to its inhibitory effect on overall protein degradation [191]. Another proteasome inhibitor Carfizomib, which is different from bortezomib in terms of their structures and mechanisms of inhibiting proteasome, has been used for the treating MM patients [192]. However, it has been found that both Bortezomib and Carfilzomib cannot be managed orally that limits their clinical application [193, 194]. Interestingly, ester bond-containing tea polyphenols, which were found in the serum of green tea drinkers are able to inhibit the function of the proteasome and cause G1 arrest in cancer cells [195]. Some synthetic polyphenol analogs have been synthesized to improve their suppressive efficacy on proteasome and enhance their anti-cancer activities [196-198]. Later, the same group identified other natural compounds targeting proteasome from plants, such as tannic acids, which induce G1 arrest and apoptosis in tumor cells [199, 200]. A new Streptomyces metabolite, belactosin, and AM114, a boronic chalcone derivative were also identified as effective proteasome inhibitors to induce G2/M arrest and cell growth inhibition in cancer cells [201, 202]. Besides these compounds, several other peptides were also reported to inhibit the activity of proteasome [203-205]. Recently, multiple proteasome inhibitors such as Oprozomib, Delanzomib, and Marizomib have been developed, and are used for clinical trials [206, 207]. Strikingly, Carfilzomib has been used for the treatment of multiple myeloma [192]. However, as proteasome is the major site to govern the degradation of the ubiquitinated proteins, off-targets effects would be expected in further pursuing the anticlinical effects of these proteasomal inhibitors.

Table 4.

The list of compounds targeting the proteasome activity

| Compound | Target and function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | The first drug approved by FDA to treat multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma | [189, 190] |

| Ester bond-containing tea polyphenols | In the serum of green tea drinker, inhibits the function of the proteasome | [195] |

| Synthetic polyphenol analogs | Improve its suppressive efficacy on proteasome | [196-198] |

| Tannic acids | Inhibit proteasome activity | [199, 200] |

| Belactosin | A new Streptomyces metabolite, effective proteasome inhibitor | [201] |

| AM114 | A boronic chalcone derivative, inhibits proteasome | [202] |

| Arecoline oxide tripeptide derivatives | Inhibitors of mammalian 20S proteasome | [203] |

| Tyropeptins A/B | Selective inhibitors of mammalian 20S proteasome | [204, 205] |

| Oprozomib, Delanzomib, Marizomib | Inhibit the activity of proteasome | [206, 207] |

2.5. Targeting deubiquitinases (DUBs)

The deubiquitinating enzymes, also known as DUBs, cleave and remove ubiquitins from proteins and other molecules [208]. In humans, there are almost 100 DUB genes that have been identified, and these are mainly classified into two categories: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases [209]. The ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Machado-Josephin domain proteases (MJDs) and ovarian tumor proteases (OUT) belong to the cysteine protease group, whereas the Jab1/Mov34/Mpr1 Pad1 N-terminal+ (MPN+) (JAMM) domain proteases belongs to the metalloprotease group [210]. It has been documented that DUBs play a crucial role in cancer development and progression. For instance, it has been demonstrated that USP1 levels are significantly elevated in osteosarcoma [211], and USP7 overexpression is critically involved in aggressive prostate cancers [212]. USP1 deubiquitinates and thereby stabilized IDs (inhibitor of DNA binding proteins) 1, ID2, and ID3, which promotes stem cell characteristics in osteosarcoma cells [211]. USP7 has been shown to inactivate several tumor suppressors including P53, FOXO4 (Forkhead box O4) and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) through different mechanisms, which lead to tumorigenesis [213-215].

As DUBs have been found to actively participate in governing tumorigenesis [216], DUB inhibitors evolved as potential anti-cancer agents [217]. To this end, several DUB inhibitors have been discovered that have profound effects in inhibiting tumorigenesis (Table 5). For example, a general DUB inhibitor WP1130 has been known to inhibit the activities of USP9x, USP5, USP14 and UCH37 that regulate the survival proteins stability [218]. WP1130-mediated inhibition of DUB activity resulted in a downregulation of anti-apoptotic protein MCL-1 and an upregulation of pro-apoptotic protein p53, leading to anti-tumor activity [218]. Further study has shown that WP1130 treatment led to ERG (E-twenty-six related gene) degradation, resulting in an inhibition of growth in ERG-positive tumors in xenograft models [219]. Although two inhibitors namely pimozide and GW7647 were reported to selectively inhibit USP1/UAF1, they also inhibited other DUBs, deSUMOlyase and cysteine proteases [220]. Importantly, these USP1 inhibitors synergistically prevented proliferation of cisplatin-resistant cancer cells, when combined with cisplatin [220]. Remarkably, this group also reported that another inhibitor of the USP1-UAF1 deubiquitinase complex, ML323, selectively inhibited human DUBs, deneddylase, and deSUMOylase [221]. As such, ML323 enhanced cisplatin cytotoxicity in osteosarcoma cells and non-small cell lung cancer cells [221].

Table 5.

The list of compounds targeting deubiquitinases

| Compound | Target and function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| WP1130 | Inhibits the activities of USP9x, USP5, USP14 and UCH37 that regulate the survival proteins stability | [218] |

| Pimozide and GW7647 | Selectively inhibit USP1/UAF1, also inhibit other DUBs, deSUMOlyase and cysteine proteases | [220] |

| ML323 | Inhibitor of the USP1-UAF1 deubiquitinase complex, selectively inhibits human DUBs, deneddylase and deSUMOylase | [221] |

| HBX 41,108 | A inhibitor of USP7, stabilizes and activate p53, inhibits cancer cell growth and induces of p53-dependent apoptosis | [222] |

| P5091 | A USP7 inhibitor, induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells that are resistant to conventional anti-cancer therapies | [223] |

| Compound 1 | Selective dual inhibitor of USP7 and USP47, induces accumulation of p53 and apoptosis in human cancer cell lines | [224] |

| IU1 | The USP14 inhibitor, enhances the degradation of oxidized proteins and causes resistance to oxidative stress | [225, 226] |

| b-AP15 | Selectively blocks deubiquitylating activity of USP14 and UCHL5, inhibits cell growth and overcomes bortezomib resistance in MM cells | [227] |

A small-molecule inhibitor of USP7, HBX 41,108, was recently reported to stabilize and activate p53, leading to inhibiting cancer cell growth and induction of p53-dependent apoptosis [222]. Furthermore, a selective USP7 inhibitor, P5091, was found to induce apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells that are resistant to conventional anti-cancer therapies [223]. Notably, selective dual inhibitors of USP7 and USP47 have been synthesized and induced accumulation of p53 and apoptosis in human cancer cell lines [224]. Moreover, these compounds demonstrated their anti-tumor activity in xenograft multiple myeloma and B-cell leukemia in vivo models [224]. Furthermore, several groups have discovered that the USP14 inhibitors could enhance the degradation of oxidized proteins and cause resistance to oxidative stress [225, 226]. In line with this, Tian et al. reported that b-AP15 selectively blocks deubiquitylating activity of USP14 and UCHL5, leading to the inhibition of cell growth and overcoming bortezomib resistance in MM cells [227]. Moreover, b-AP15 treatment inhibited the expression of Cdc25c, Cdc2, and cyclin B1 and subsequently induced cellular apoptosis. Furthermore, b-AP15 retarded tumor growth and prolonged survival in human MM xenograft mouse models [227]. These studies together suggest that inhibiting specific oncogenic DUBs could be an effective anti-cancer approach.

3. Discussion and perspective

Numerous natural and synthetic compounds have been shown to target various components of the UPS to regulate protein homeostasis through proteasome-mediated degradation in cells [228] (Figure 1). Recent discoveries in ubiquitin proteasome field and identification of specific sub-set of molecules in E3 ligase complexes further provided new opportunities to develop novel synthetic drug molecules that modify the UPS function to prevent cancer development [229]. These promising molecules evolved as new anti-cancer compounds in the drug developing industry. This protein degradation-based anti-cancer strategy should draw more attentions in near future, due to its unique advantages to timely and specifically regulate either tumor suppressors or oncoproteins [230]. For instance, some E3 ligases such as β-TRCP have multiple oncogene or tumor suppressor substrates, and thus, targeting them may produce higher anti-cancer effects than targeting a single oncogene or tumor suppressor [80]. However, targeting the Fbw7 E3 ligase has its own advantage due to its unique function as a tumor suppressor [231]. To this end, compounds that increase endogenous Fbw7 levels or its activity will serve as better anti-cancer therapeutics due to its capability of degrading multiple oncoproteins including c-Myc, c-Jun, Cyclin E and Notch-1 [232].

Furthermore, compounds that target deubiquitinating enzymes also have unique added advantages in preventing various cancers by inhibiting protein degradation especially the tumor suppressors. Additionally, marine organisms, such as Sponges, Tunicates and Mollusks, are promising source for bioactive compounds that target UPS to prevent cancer [228]. In fact, some UPS targeting drugs, such as Himeic acid A, Largazole and Leucettamol A were derived from marine creatures. Therefore, we believe that E3 ligase complex-specific compounds and DUB inhibitors, which target ubiquitin proteasome system, will attract more attention in future research due to their profound effects on regulating cancer causing proteins as well as tumor suppressors in cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH grants to W.W. (GM089763, GM094777 and CA177910). W.W. is an ACS research scholar and a LLS research scholar. This work was also supported by grant from NSFC (81172087) and a project funded by the priority academic program development of Jiangsu higher education institutions.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chondrogianni N, Petropoulos I, Grimm S, Georgila K, Catalgol B, Friguet B, Grune T, Gonos ES. Protein damage, repair and proteolysis. Mol Aspects Med. 2014;35:1–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christianson JC, Ye Y. Cleaning up in the endoplasmic reticulum: ubiquitin in charge. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:325–335. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacGurn JA, Hsu PC, Emr SD. Ubiquitin and membrane protein turnover: from cradle to grave. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:231–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060210-093619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciechanover A. Intracellular protein degradation: from a vague idea through the lysosome and the ubiquitin-proteasome system and onto human diseases and drug targeting. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:3400–3410. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosesson Y, Mills GB, Yarden Y. Derailed endocytosis: an emerging feature of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:835–850. doi: 10.1038/nrc2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Liu P, Inuzuka H, Wei W. Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrc3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedford L, Lowe J, Dick LR, Mayer RJ, Brownell JE. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation and the ubiquitin-proteasome system as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:29–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman AM. Themes and variations on ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35056563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vucic D, Dixit VM, Wertz IE. Ubiquitylation in apoptosis: a post-translational modification at the edge of life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:439–452. doi: 10.1038/nrm3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman AM, Shabek N, Ciechanover A. The predator becomes the prey: regulating the ubiquitin system by ubiquitylation and degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:605–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipkowitz S, Weissman AM. RINGs of good and evil: RING finger ubiquitin ligases at the crossroads of tumour suppression and oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:629–643. doi: 10.1038/nrc3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skaar JR, Pagan JK, Pagano M. Mechanisms and function of substrate recruitment by F-box proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrm3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderica-Romero AC, Gonzalez-Herrera IG, Santamaria A, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Cullin 3 as a novel target in diverse pathologies. Redox Biol. 2013;1:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genschik P, Sumara I, Lechner E. The emerging family of CULLIN3-RING ubiquitin ligases (CRL3s): cellular functions and disease implications. Embo J. 2013;32:2307–2320. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, Sun Y. Cullin-RING Ligases as attractive anti-cancer targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:3215–3225. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Zhou P. Cullins and cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:690–699. doi: 10.1177/1947601910382899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekizawa R, Ikeno S, Nakamura H, Naganawa H, Matsui S, Iinuma H, Takeuchi T. Panepophenanthrin from a mushroom strain, a novel inhibitor of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:1491–1493. doi: 10.1021/np020098q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moses JE, Commeiras L, Baldwin JE, Adlington RM. Total synthesis of panepophenanthrin. Org Lett. 2003;5:2987–2988. doi: 10.1021/ol0349817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei X, Johnson RP, Porco JA., Jr Total synthesis of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme inhibitor (+)-panepophenanthrin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:3913–3917. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Lee D. Application of a tandem metathesis to the synthesis of (+)-panepophenanthrin. Chem Asian J. 2010;5:1298–1302. doi: 10.1002/asia.200900724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuzawa M, Kakeya H, Yamaguchi J, Shoji M, Onose R, Osada H, Hayashi Y. Enantio- and diastereoselective total synthesis of (+)-panepophenanthrin, a ubiquitin-activating enzyme inhibitor, and biological properties of its new derivatives. Chem Asian J. 2006;1:845–851. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsukamoto S, Hirota H, Imachi M, Fujimuro M, Onuki H, Ohta T, Yokosawa H. Himeic acid A: a new ubiquitin-activating enzyme inhibitor isolated from a marine-derived fungus, Aspergillus sp. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ungermannova D, Parker SJ, Nasveschuk CG, Wang W, Quade B, Zhang G, Kuchta RD, Phillips AJ, Liu X. Largazole and its derivatives selectively inhibit ubiquitin activating enzyme (e1) PLoS One. 2012;7:e29208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu LC, Wen ZS, Qiu YT, Chen XQ, Chen HB, Wei MM, Liu Z, Jiang S, Zhou GB. Largazole Arrests Cell Cycle at G1 Phase and Triggers Proteasomal Degradation of E2F1 in Lung Cancer Cells. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:921–926. doi: 10.1021/ml400093y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamanokuchi R, Imada K, Miyazaki M, Kato H, Watanabe T, Fujimuro M, Saeki Y, Yoshinaga S, Terasawa H, Iwasaki N, Rotinsulu H, Losung F, Mangindaan RE, Namikoshi M, de Voogd NJ, Yokosawa H, Tsukamoto S. Hyrtioreticulins A-E, indole alkaloids inhibiting the ubiquitin-activating enzyme, from the marine sponge Hyrtios reticulatus. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:4437–4442. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen JJ, Tsu CA, Gavin JM, Milhollen MA, Bruzzese FJ, Mallender WD, Sintchak MD, Bump NJ, Yang X, Ma J, Loke HK, Xu Q, Li P, Bence NF, Brownell JE, Dick LR. Mechanistic studies of substrate-assisted inhibition of ubiquitin-activating enzyme by adenosine sulfamate analogues. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40867–40877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, Kitagaki J, Dai RM, Tsai YC, Lorick KL, Ludwig RL, Pierre SA, Jensen JP, Davydov IV, Oberoi P, Li CC, Kenten JH, Beutler JA, Vousden KH, Weissman AM. Inhibitors of ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), a new class of potential cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9472–9481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson IR, Irwin MS, Ohh M. NEDD8 pathways in cancer, Sine Quibus Non. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soucy TA, Dick LR, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Brownell JE. The NEDD8 Conjugation Pathway and Its Relevance in Cancer Biology and Therapy. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:708–716. doi: 10.1177/1947601910382898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Berger AJ, Gavin JM, Adhikari S, Brownell JE, Burke KE, Cardin DP, Critchley S, Cullis CA, Doucette A, Garnsey JJ, Gaulin JL, Gershman RE, Lublinsky AR, McDonald A, Mizutani H, Narayanan U, Olhava EJ, Peluso S, Rezaei M, Sintchak MD, Talreja T, Thomas MP, Traore T, Vyskocil S, Weatherhead GS, Yu J, Zhang J, Dick LR, Claiborne CF, Rolfe M, Bolen JB, Langston SP. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature. 2009;458:732–736. doi: 10.1038/nature07884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nawrocki ST, Griffin P, Kelly KR, Carew JS. MLN4924: a novel first-in-class inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1563–1573. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.707192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong HJ, Ma VP, Cheng Z, Chan DS, He HZ, Leung KH, Ma DL, Leung CH. Discovery of a natural product inhibitor targeting protein neddylation by structure-based virtual screening. Biochimie. 2012;94:2457–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ceccarelli DF, Tang X, Pelletier B, Orlicky S, Xie W, Plantevin V, Neculai D, Chou YC, Ogunjimi A, Al-Hakim A, Varelas X, Koszela J, Wasney GA, Vedadi M, Dhe-Paganon S, Cox S, Xu S, Lopez-Girona A, Mercurio F, Wrana J, Durocher D, Meloche S, Webb DR, Tyers M, Sicheri F. An allosteric inhibitor of the human Cdc34 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Cell. 2011;145:1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harper JW, King RW. Stuck in the middle: drugging the ubiquitin system at the e2 step. Cell. 2011;145:1007–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsukamoto S, Takeuchi T, Rotinsulu H, Mangindaan RE, van Soest RW, Ukai K, Kobayashi H, Namikoshi M, Ohta T, Yokosawa H. Leucettamol A: a new inhibitor of Ubc13-Uev1A interaction isolated from a marine sponge, Leucetta aff microrhaphis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:6319–6320. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ushiyama S, Umaoka H, Kato H, Suwa Y, Morioka H, Rotinsulu H, Losung F, Mangindaan RE, de Voogd NJ, Yokosawa H, Tsukamoto S. Manadosterols A and B, sulfonated sterol dimers inhibiting the Ubc13-Uev1A interaction, isolated from the marine sponge Lissodendryx fibrosa. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:1495–1499. doi: 10.1021/np300352u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petroski MD, Zhou X, Dong G, Daniel-Issakani S, Payan DG, Huang J. Substrate modification with lysine 63-linked ubiquitin chains through the UBC13-UEV1A ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29936–29945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamothe B, Besse A, Campos AD, Webster WK, Wu H, Darnay BG. Site-specific Lys-63-linked tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 auto-ubiquitination is a critical determinant of I kappa B kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4102–4112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609503200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, Grim JE, Harper JW, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Kamura T, Nishiyama M, Tsunematsu R, Imaki H, Ishida N, Okumura F, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. Embo J. 2004;23:2116–2125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moberg KH, Mukherjee A, Veraksa A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila F box protein archipelago regulates dMyc protein levels in vivo. Curr Biol. 2004;14:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nateri AS, Riera-Sans L, Da Costa C, Behrens A. The ubiquitin ligase SCFFbw7 antagonizes apoptotic JNK signaling. Science. 2004;303:1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.1092880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei W, Jin J, Schlisio S, Harper JW, Kaelin WG., Jr The v-Jun point mutation allows c-Jun to escape GSK3-dependent recognition and destruction by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strohmaier H, Spruck CH, Kaiser P, Won KA, Sangfelt O, Reed SI. Human F-box protein hCdc4 targets cyclin E for proteolysis and is mutated in a breast cancer cell line. Nature. 2001;413:316–322. doi: 10.1038/35095076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moberg KH, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. Archipelago regulates Cyclin E levels in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Nature. 2001;413:311–316. doi: 10.1038/35095068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koepp DM, Schaefer LK, Ye X, Keyomarsi K, Chu C, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2001;294:173–177. doi: 10.1126/science.1065203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao JH, Kim IJ, Wu D, Climent J, Kang HC, DelRosario R, Balmain A. FBXW7 targets mTOR for degradation and cooperates with PTEN in tumor suppression. Science. 2008;321:1499–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1162981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inuzuka H, Shaik S, Onoyama I, Gao D, Tseng A, Maser RS, Zhai B, Wan L, Gutierrez A, Lau AW, Xiao Y, Christie AL, Aster J, Settleman J, Gygi SP, Kung AL, Look T, Nakayama KI, DePinho RA, Wei W. SCF(FBW7) regulates cellular apoptosis by targeting MCL1 for ubiquitylation and destruction. Nature. 2011;471:104–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wertz IE, Kusam S, Lam C, Okamoto T, Sandoval W, Anderson DJ, Helgason E, Ernst JA, Eby M, Liu J, Belmont LD, Kaminker JS, O’Rourke KM, Pujara K, Kohli PB, Johnson AR, Chiu ML, Lill JR, Jackson PK, Fairbrother WJ, Seshagiri S, Ludlam MJ, Leong KG, Dueber EC, Maecker H, Huang DC, Dixit VM. Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature. 2011;471:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature09779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassavaugh JM, Hale SA, Wellman TL, Howe AK, Wong C, Lounsbury KM. Negative regulation of HIF-1alpha by an FBW7-mediated degradation pathway during hypoxia. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:3882–3890. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flugel D, Gorlach A, Kietzmann T. GSK-3beta regulates cell growth, migration, and angiogenesis via Fbw7 and USP28-dependent degradation of HIF-1alpha. Blood. 2012;119:1292–1301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu N, Li H, Li S, Shen M, Xiao N, Chen Y, Wang Y, Wang W, Wang R, Wang Q, Sun J, Wang P. The Fbw7/human CDC4 tumor suppressor targets proproliferative factor KLF5 for ubiquitination and degradation through multiple phosphodegron motifs. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18858–18867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.099440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao D, Zheng HQ, Zhou Z, Chen C. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor targets KLF5 for ubiquitin-mediated degradation and suppresses breast cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4728–4738. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis MA, Larimore EA, Fissel BM, Swanger J, Taatjes DJ, Clurman BE. The SCF-Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase degrades MED13 and MED13L and regulates CDK8 module association with Mediator. Genes Dev. 2013;27:151–156. doi: 10.1101/gad.207720.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang R, Wang Y, Liu N, Ren C, Jiang C, Zhang K, Yu S, Chen Y, Tang H, Deng Q, Fu C, Li R, Liu M, Pan W, Wang P. FBW7 regulates endothelial functions by targeting KLF2 for ubiquitination and degradation. Cell Res. 2013;23:803–819. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fukushima H, Matsumoto A, Inuzuka H, Zhai B, Lau AW, Wan L, Gao D, Shaik S, Yuan M, Gygi SP, Jimi E, Asara JM, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Wei W. SCF(Fbw7) modulates the NFkB signaling pathway by targeting NFkB2 for ubiquitination and destruction. Cell Rep. 2012;1:434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Busino L, Millman SE, Scotto L, Kyratsous CA, Basrur V, O’Connor O, Hoffmann A, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Pagano M. Fbxw7alpha- and GSK3-mediated degradation of p100 is a pro-survival mechanism in multiple myeloma. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:375–385. doi: 10.1038/ncb2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lochab S, Pal P, Kapoor I, Kanaujiya JK, Sanyal S, Behre G, Trivedi AK. E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbw7 negatively regulates granulocytic differentiation by targeting G-CSFR for degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2639–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu G, Lyapina S, Das I, Li J, Gurney M, Pauley A, Chui I, Deshaies RJ, Kitajewski J. SEL-10 is an inhibitor of notch signaling that targets notch for ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7403–7415. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7403-7415.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta-Rossi N, Le Bail O, Gonen H, Brou C, Logeat F, Six E, Ciechanover A, Israel A. Functional interaction between SEL-10, an F-box protein, and the nuclear form of activated Notch1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34371–34378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oberg C, Li J, Pauley A, Wolf E, Gurney M, Lendahl U. The Notch intracellular domain is ubiquitinated and negatively regulated by the mammalian Sel-10 homolog. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35847–35853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kimura T, Gotoh M, Nakamura Y, Arakawa H. hCDC4b, a regulator of cyclin E, as a direct transcriptional target of p53. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mao JH, Perez-Losada J, Wu D, Delrosario R, Tsunematsu R, Nakayama KI, Brown K, Bryson S, Balmain A. Fbxw7/Cdc4 is a p53-dependent, haploinsufficient tumour suppressor gene. Nature. 2004;432:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nature03155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balamurugan K, Wang JM, Tsai HH, Sharan S, Anver M, Leighty R, Sterneck E. The tumour suppressor C/EBPdelta inhibits FBXW7 expression and promotes mammary tumour metastasis. EMBO J. 2010;29:4106–4117. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu Y, Sengupta T, Kukreja L, Minella AC. MicroRNA-223 regulates cyclin E activity by modulating expression of F-box and WD-40 domain protein 7. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34439–34446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.152306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J, Guo Y, Liang X, Sun M, Wang G, De W, Wu W. MicroRNA-223 functions as an oncogene in human gastric cancer by targeting FBXW7/hCdc4. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:763–774. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1154-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lerner M, Lundgren J, Akhoondi S, Jahn A, Ng HF, Akbari Moqadam F, Oude Vrielink JA, Agami R, Den Boer ML, Grander D, Sangfelt O. MiRNA-27a controls FBW7/hCDC4-dependent cyclin E degradation and cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2172–2183. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.13.16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spruck C. miR-27a regulation of SCF(Fbw7) in cell division control and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3232–3233. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.19.17125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang HL, Weng HY, Wang LQ, Yu CH, Huang QJ, Zhao PP, Wen JZ, Zhou H, Qu LH. Triggering Fbw7-mediated proteasomal degradation of c-Myc by oridonin induces cell growth inhibition and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1155–1165. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma J, Cheng L, Liu H, Zhang J, Shi Y, Zeng F, Miele L, Sarkar FH, Xia J, Wang Z. Genistein down-regulates miR-223 expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14:1150–1156. doi: 10.2174/13894501113149990187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Orlicky S, Tang X, Neduva V, Elowe N, Brown ED, Sicheri F, Tyers M. An allosteric inhibitor of substrate recognition by the SCF(Cdc4) ubiquitin ligase. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:733–737. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Z, Gao D, Fukushima H, Inuzuka H, Liu P, Wan L, Sarkar FH, Wei W. Skp2: a novel potential therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu ZK, Gervais JL, Zhang H. Human CUL-1 associates with the SKP1/SKP2 complex and regulates p21(CIP1/WAF1) and cyclin D proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsvetkov LM, Yeh KH, Lee SJ, Sun H, Zhang H. p27(Kip1) ubiquitination and degradation is regulated by the SCF(Skp2) complex through phosphorylated Thr187 in p27. Curr Biol. 1999;9:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kamura T, Hara T, Kotoshiba S, Yada M, Ishida N, Imaki H, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI. Degradation of p57Kip2 mediated by SCFSkp2-dependent ubiquitylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10231–10236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831009100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Inuzuka H, Gao D, Finley LW, Yang W, Wan L, Fukushima H, Chin YR, Zhai B, Shaik S, Lau AW, Wang Z, Gygi SP, Nakayama K, Teruya-Feldstein J, Toker A, Haigis MC, Pandolfi PP, Wei W. Acetylation-dependent regulation of Skp2 function. Cell. 2012;150:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang H, Regan KM, Wang F, Wang D, Smith DI, van Deursen JM, Tindall DJ. Skp2 inhibits FOXO1 in tumor suppression through ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1649–1654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406789102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang G, Chan CH, Gao Y, Lin HK. Novel roles of Skp2 E3 ligase in cellular senescence, cancer progression, and metastasis. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31:169–177. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Radke S, Pirkmaier A, Germain D. Differential expression of the F-box proteins Skp2 and Skp2B in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:3448–3458. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fujita T, Liu W, Doihara H, Date H, Wan Y. Dissection of the APCCdh1-Skp2 cascade in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1966–1975. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang J, Huang Y, Guan Z, Zhang JL, Su HK, Zhang W, Yue CF, Yan M, Guan S, Liu QQ. E3-ligase Skp2 predicts poor prognosis and maintains cancer stem cell pool in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5591–5601. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chan CH, Lee SW, Wang J, Lin HK. Regulation of Skp2 expression and activity and its role in cancer progression. The Scientific World Journal. 2010;10:1001–1015. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chan CH, Morrow JK, Zhang S, Lin HK. Skp2: a dream target in the coming age of cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:679–680. doi: 10.4161/cc.27853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu L, Grigoryan AV, Li Y, Hao B, Pagano M, Cardozo TJ. Specific small molecule inhibitors of Skp2-mediated p27 degradation. Chem Biol. 2012;19:1515–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Q, Xie W, Kuhn DJ, Voorhees PM, Lopez-Girona A, Mendy D, Corral LG, Krenitsky VP, Xu W, Moutouh-de Parseval L, Webb DR, Mercurio F, Nakayama KI, Nakayama K, Orlowski RZ. Targeting the p27 E3 ligase SCF(Skp2) results in p27- and Skp2-mediated cell-cycle arrest and activation of autophagy. Blood. 2008;111:4690–4699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chan CH, Morrow JK, Li CF, Gao Y, Jin G, Moten A, Stagg LJ, Ladbury JE, Cai Z, Xu D, Logothetis CJ, Hung MC, Zhang S, Lin HK. Pharmacological inactivation of Skp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase restricts cancer stem cell traits and cancer progression. Cell. 2013;154:556–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rico-Bautista E, Yang CC, Lu L, Roth GP, Wolf DA. Chemical genetics approach to restoring p27Kip1 reveals novel compounds with antiproliferative activity in prostate cancer cells. BMC Biol. 2010;8:153. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roy S, Kaur M, Agarwal C, Tecklenburg M, Sclafani RA, Agarwal R. p21 and p27 induction by silibinin is essential for its cell cycle arrest effect in prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2696–2707. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang ES, Burnstein KL. Vitamin D inhibits G1 to S progression in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through p27Kip1 stabilization and Cdk2 mislocalization to the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46862–46868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang HC, Lin CL, Lin JK. 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-beta-D-glucose, quercetin, curcumin and lycopene induce cell-cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 and BT474 cells through downregulation of Skp2 protein. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:6765–6775. doi: 10.1021/jf201096v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang HC, Way TD, Lin CL, Lin JK. EGCG stabilizes p27kip1 in E2-stimulated MCF-7 cells through down-regulation of the Skp2 protein. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5972–5983. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Busino L, Donzelli M, Chiesa M, Guardavaccaro D, Ganoth D, Dorrello NV, Hershko A, Pagano M, Draetta GF. Degradation of Cdc25A by beta-TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2003;426:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature02082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jin J, Shirogane T, Xu L, Nalepa G, Qin J, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. SCFbeta-TRCP links Chk1 signaling to degradation of the Cdc25A protein phosphatase. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3062–3074. doi: 10.1101/gad.1157503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13:270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tan M, Gallegos JR, Gu Q, Huang Y, Li J, Jin Y, Lu H, Sun Y. SAG/ROC-SCF beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase promotes pro-caspase-3 degradation as a mechanism of apoptosis protection. Neoplasia. 2006;8:1042–1054. doi: 10.1593/neo.06568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guardavaccaro D, Kudo Y, Boulaire J, Barchi M, Busino L, Donzelli M, Margottin-Goguet F, Jackson PK, Yamasaki L, Pagano M. Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein beta-Trcp1 in vivo. Dev Cell. 2003;4:799–812. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Margottin-Goguet F, Hsu JY, Loktev A, Hsieh HM, Reimann JD, Jackson PK. Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF(betaTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev Cell. 2003;4:813–826. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Inuzuka H, Tseng A, Gao D, Zhai B, Zhang Q, Shaik S, Wan L, Ang XL, Mock C, Yin H, Stommel JM, Gygi S, Lahav G, Asara J, Xiao ZX, Kaelin WG, Jr, Harper JW, Wei W. Phosphorylation by casein kinase I promotes the turnover of the Mdm2 oncoprotein via the SCF(beta-TRCP) ubiquitin ligase. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Strack P, Caligiuri M, Pelletier M, Boisclair M, Theodoras A, Beer-Romero P, Glass S, Parsons T, Copeland RA, Auger KR, Benfield P, Brizuela L, Rolfe M. SCF(beta-TRCP) and phosphorylation dependent ubiquitinationof I kappa B alpha catalyzed by Ubc3 and Ubc4. Oncogene. 2000;19:3529–3536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dorrello NV, Peschiaroli A, Guardavaccaro D, Colburn NH, Sherman NE, Pagano M. S6K1- and betaTRCP-mediated degradation of PDCD4 promotes protein translation and cell growth. Science. 2006;314:467–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1130276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu Y, Lee SH, Kim HS, Kim NH, Piao S, Park SH, Jung YS, Yook JI, Park BJ, Ha NC. Role of CK1 in GSK3beta-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of snail. Oncogene. 2010;29:3124–3133. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhong J, Shaik S, Wan L, Tron AE, Wang Z, Sun L, Inuzuka H, Wei W. SCF beta-TRCP targets MTSS1 for ubiquitination-mediated destruction to regulate cancer cell proliferation and migration. Oncotarget. 2013;4:2339–2353. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, Taniguchi M, Hunter T, Osada H. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFbeta-TrCP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lau AW, Fukushima H, Wei W. The Fbw7 and betaTRCP E3 ubiquitin ligases and their roles in tumorigenesis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2197–2212. doi: 10.2741/4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Muerkoster S, Arlt A, Sipos B, Witt M, Grossmann M, Kloppel G, Kalthoff H, Folsch UR, Schafer H. Increased expression of the E3-ubiquitin ligase receptor subunit betaTRCP1 relates to constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB activation and chemoresistance in pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1316–1324. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Saitoh T, Katoh M. Expression profiles of betaTRCP1 and betaTRCP2, and mutation analysis of betaTRCP2 in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:959–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ougolkov A, Zhang B, Yamashita K, Bilim V, Mai M, Fuchs SY, Minamoto T. Associations among beta-TrCP, an E3 ubiquitin ligase receptor, beta-catenin, and NF-kappaB in colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1161–1170. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kudo Y, Guardavaccaro D, Santamaria PG, Koyama-Nasu R, Latres E, Bronson R, Yamasaki L, Pagano M. Role of F-box protein betaTrcp1 in mammary gland development and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8184–8194. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8184-8194.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tang W, Li Y, Yu D, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Spiegelman V, Fuchs SY. Targeting beta-transducin repeat-containing protein E3 ubiquitin ligase augments the effects of antitumor drugs on breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1904–1908. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schmid T, Jansen AP, Baker AR, Hegamyer G, Hagan JP, Colburn NH. Translation inhibitor Pdcd4 is targeted for degradation during tumor promotion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1254–1260. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Blees JS, Bokesch HR, Rubsamen D, Schulz K, Milke L, Bajer MM, Gustafson KR, Henrich CJ, McMahon JB, Colburn NH, Schmid T, Brune B. Erioflorin stabilizes the tumor suppressor Pdcd4 by inhibiting its interaction with the E3-ligase beta-TrCP1. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nangle S, Xing W, Zheng N. Crystal structure of mammalian cryptochrome in complex with a small molecule competitor of its ubiquitin ligase. Cell Res. 2013;23:1417–1419. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mallampalli RK, Coon TA, Glasser JR, Wang C, Dunn SR, Weathington NM, Zhao J, Zou C, Zhao Y, Chen BB. Targeting F box protein Fbxo3 to control cytokine-driven inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;191:5247–5255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Xing W, Busino L, Hinds TR, Marionni ST, Saifee NH, Bush MF, Pagano M, Zheng N. SCF(FBXL3) ubiquitin ligase targets cryptochromes at their cofactor pocket. Nature. 2013;496:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature11964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Z, Wan L, Zhong J, Inuzuka H, Liu P, Sarkar FH, Wei W. Cdc20: a potential novel therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:3210–3214. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319180005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zur A, Brandeis M. Securin degradation is mediated by fzy and fzr, and is required for complete chromatid separation but not for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 2001;20:792–801. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lim HH, Goh PY, Surana U. Cdc20 is essential for the cyclosome-mediated proteolysis of both Pds1 and Clb2 during M phase in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 1998;8:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shirayama M, Toth A, Galova M, Nasmyth K. APC(Cdc20) promotes exit from mitosis by destroying the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 and cyclin Clb5. Nature. 1999;402:203–207. doi: 10.1038/46080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Geley S, Kramer E, Gieffers C, Gannon J, Peters JM, Hunt T. Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-dependent proteolysis of human cyclin A starts at the beginning of mitosis and is not subject to the spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:137–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ohtoshi A, Maeda T, Higashi H, Ashizawa S, Hatakeyama M. Human p55(CDC)/Cdc20 associates with cyclin A and is phosphorylated by the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:530–534. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Amador V, Ge S, Santamaria PG, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. APC/C(Cdc20) controls the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p21 in prometaphase. Mol Cell. 2007;27:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Harley ME, Allan LA, Sanderson HS, Clarke PR. Phosphorylation of Mcl-1 by CDK1-cyclin B1 initiates its Cdc20-dependent destruction during mitotic arrest. EMBO J. 2010;29:2407–2420. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zeng X, Sigoillot F, Gaur S, Choi S, Pfaff KL, Oh DC, Hathaway N, Dimova N, Cuny GD, King RW. Pharmacologic inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex induces a spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest in the absence of spindle damage. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zeng X, King RW. An APC/C inhibitor stabilizes cyclin B1 by prematurely terminating ubiquitination. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:383–392. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sackton KL, Dimova N, Zeng X, Tian W, Zhang M, Sackton TB, Meaders J, Pfaff KL, Sigoillot F, Yu H, Luo X, King RW. Synergistic blockade of mitotic exit by two chemical inhibitors of the APC/C. Nature. 2014;514:646–649. doi: 10.1038/nature13660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Jiang J, Thyagarajan-Sahu A, Krchnak V, Jedinak A, Sandusky GE, Sliva D. NAHA, a novel hydroxamic acid-derivative, inhibits growth and angiogenesis of breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]