Abstract

Usher syndrome (USH), clinically and genetically heterogeneous, is the leading genetic cause of combined hearing and vision loss. USH is classified into three types, based on the hearing and vestibular symptoms observed in patients. Sixteen loci have been reported to be involved in the occurrence of USH and atypical USH. Among them, twelve have been identified as causative genes and one as a modifier gene. Studies on the proteins encoded by these USH genes suggest that USH proteins interact among one another and function in multiprotein complexes in vivo. Although their exact functions remain enigmatic in the retina, USH proteins are required for the development, maintenance and function of hair bundles, which are the primary mechanosensitive structure of inner ear hair cells. Despite the unavailability of a cure, progress has been made to develop effective treatments for this disease. In this review, we focus on the most recent discoveries in the field with an emphasis on USH genes, protein complexes and functions in various tissues as well as progress toward therapeutic development for USH.

Keywords: Retina photoreceptor, inner ear hair cell, hair bundle link, periciliary membrane complex, USH multiprotein complex, therapy

1. Introduction

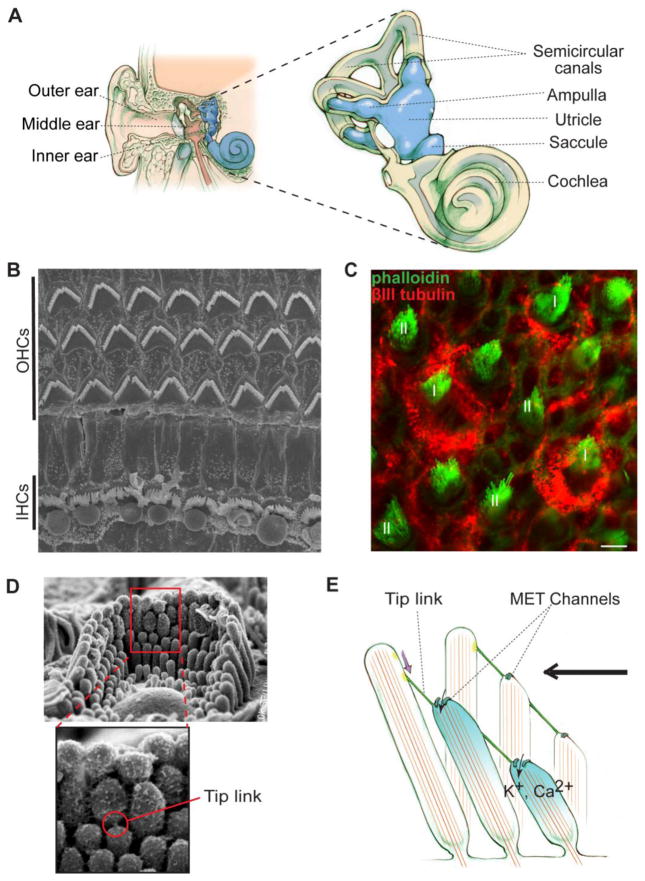

In mammals, the inner ear and retina are the two sensory organs responsible for hearing, balance and vision. The inner ear contains the cochlea and vestibular system for sensing sounds and position changes, respectively (Figure 1A). In the cochlea, the organ of Corti, the main sound-sensitive structure, has three rows of outer hair cells (OHCs) and one row of inner hair cells (IHCs) (Figure 1B). OHCs receive and amplify sound-evoked vibrations of the sensory epithelium, whereas IHCs convert the amplified mechanical signals into electrical responses [1]. The vestibular system includes the utricle and saccule for detection of linear acceleration as well as semicircular canal ampullae for detection of angular acceleration (Figure 1A) [2, 3]. Two types of hair cells, named I and II, exist in these vestibular sensory organs (Figure 1C). In both cochlear and vestibular systems, hair cells are neurons possessing a specialized mechanosensitive structure, the hair bundle, on their cellular apices (Figure 1D). Each hair bundle consists of well-organized, actin-based stereocilia graded in lengths and a long microtubule-based kinocilium, although the latter is missing in mature mammalian cochlear hair cells. Responding to sound, movement or gravity, the hair bundle deflects in the excitatory direction toward the longest stereocilia, which induces the opening of ion channels at the tip of shorter stereocilia. Influx of cations leads to membrane potential changes, thereby converting the mechanical stimuli into electrical responses (Figure 1E), a process referred to as mechanoelectrical transduction (MET) [1, 4, 5].

Figure 1.

Inner ear anatomy and mechanoelectrical transduction (MET). (A) The position and structure of the inner ear. The inner ear is the most inner part of the ear (Left). It contains the cochlea and vestibular system. The vestibular system includes the utricle, saccule and semicircular canal ampullae (Right). (B) Top view of the murine organ of Corti shown by scanning electron microscopy. The organ of Corti has one row of inner hair cells (IHCs) and three rows of outer hair cells (OHCs). (C) Type I (I) and type II (II) hair cells in the murine utricular extrastriola shown by immunofluorescence. Phalloidin signal (green) indicates actin bundles in stereocilia. βIII tubulin (red) labels calyx afferents of type I hair cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) A hair bundle shown by scanning electron microscopy. Top, an entire bundle with a staircase pattern of stereociliary organization. Bottom, an amplified view of the boxed area on the top showing a tip link. (E) MET occurs when the hair bundle is deflected toward the longest stereocilium (excitatory direction, black arrow). Deflection of hair bundles in this direction stretches tip links, which subsequently regulates the gating of MET channels and leads to hair cell depolarization. Note that this is a simplified model and tip links may associate with MET channels indirectly.

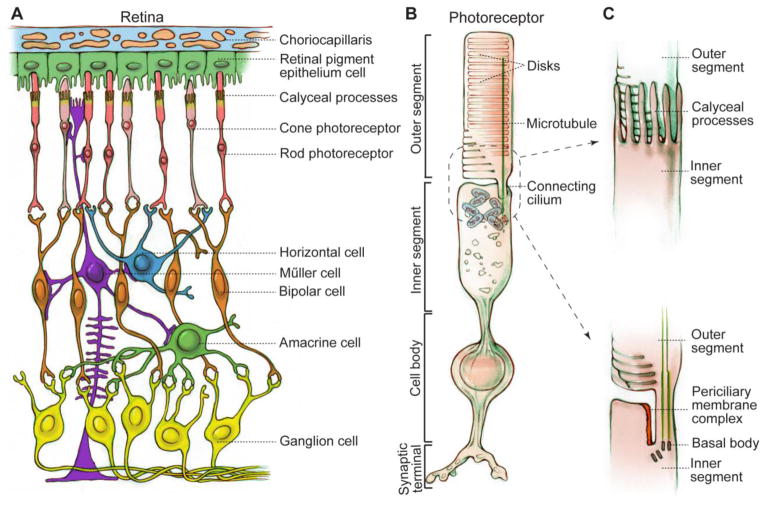

In the retina, photoreceptors (Figure 2A) are light-sensitive neurons that are highly compartmentalized. Their outer segment, a modified sensory cilium, contains many tightly-packed flat membrane disks harboring proteins involved in phototransduction (Figure 2B). This segment undergoes active and continuous renewal with their proteins and membranes synthesized in the inner segment and transported to the outer segment by intraflagellar transport through the connecting cilium. Addition of new disks proximally is balanced by shedding of old disks distally. Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells (Figure 2A) phagocytose and digest the shed photoreceptor outer segment tips and participate in visual pigment regeneration. Proximal to photoreceptors are bipolar cells, horizontal cells, amacrine cells and ganglion cells (Figure 2A). Electrical impulses, generated from phototransduction in the photoreceptor outer segment, are transmitted to the above-mentioned downstream retinal neurons at the photoreceptor ribbon synapse. Müller cells, the major glial cells in the retina (Figure 2A), have large and long radial cellular processes and form adherens junctions with photoreceptors at the proximal inner segment. Compromised photoreceptors, RPE cells and Müller cells are now thought to be the cellular basis underlying pathogenesis of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (reviewed in [6]).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of the retina and photoreceptor. (A) Cellular organization of the retina. Retinal neurons are arranged into different layers. Photoreceptors and RPE cells are located in the outer retina, while horizontal cells, bipolar cells, amacrine cells and ganglion cells are downstream neurons of photoreceptors in the inner retina. Müller cells are glial cells spanning all cell layers of the retina. (B) Photoreceptor structure exemplified by a rod. Photoreceptors are ciliated cells with several specialized subcellular compartments, consisting of an outer segment having tightly packed membrane disks, a connecting cilium with microtubules, calyceal processes with actin bundles (not shown), an inner segment having all organelles for energy and protein synthesis, a cell body containing the nucleus, and a synaptic terminus for signal transmission to bipolar and horizontal cells. (C) Magnified drawings of calyceal processes (top) and periciliary membrane complex (bottom) around the photoreceptor connecting cilium. In order to show the periciliary membrane complex, calyceal processes are omitted in the bottom drawing.

Usher syndrome (USH), an autosomal recessive genetic disease, is characterized by hearing loss, vision loss and occasional balance problems. USH, first described by the Scottish ophthalmologist, Charles Usher, is the leading genetic cause of deaf-blindness with a prevalence in the range of 1–4 per 25,000 people [7–10]. Based on diverse clinical symptoms observed in patients, USH is classified into three types. USH type I (USH1) patients are defined as having congenital severe-to-profound deafness, vestibular areflexia and onset of RP within the first decade of life. USH2 patients show congenital moderate-to-severe hearing loss, normal vestibular function and onset of RP within the second decade of life. In USH3 patients, the hearing loss, vestibular dysfunction and onset of RP are progressive, sporadic and variable, respectively. Early symptoms of RP are night blindness and loss of peripheral vision, caused by degeneration of rod photoreceptors. Upon progression of RP, cone photoreceptors also degenerate [8]. Loss of central (cone-mediated) vision results in USH patients becoming legally or completely blind with no known cure [11, 12].

Significant progress has been made recently toward the identification of USH causative genes. Through extensive study of these genes in various animal models, evidence suggests that defects in inner ear hair cell development and photoreceptor maintenance probably underlie USH pathogenesis. In this review, we will summarize the current knowledge of USH causative genes, disease mechanisms and potential treatments. We will focus on new discoveries regarding USH etiology, because several excellent and comprehensive reviews already exist in the literature [13–22].

2. Genes and loci identified in USH patients

To date, sixteen loci have been associated with USH: nine are involved in USH1, three in USH2, two in USH3 and two not specified (Table 1) [9, 23–27]. From these loci, thirteen genes have been identified. They include six USH1, three USH2, two USH3, one USH modifier and one atypical USH genes. The USH1 genes are MYO7A (myosin VIIa) [28], USH1C (harmonin) [29, 30], CDH23 (cadherin 23) [31, 32], PCDH15 (protocadherin 15) [33, 34], USH1G (SANS, scaffold protein containing ankyrin repeats and sam domain) [35] and CIB2 (calcium- and integrin-binding protein 2) [36]. The USH2 genes are USH2A (usherin) [37], GPR98 (G protein-coupled receptor 98) [38] and DFNB31 (autosomal recessive deafness 31) [39]. CLRN1 (Clarin-1) and HARS (histidyl-tRNA synthetase) are the USH3 genes [25, 40–42]. Furthermore, PDZD7 (PDZ domain containing 7) was recently discovered as an USH modifier and digenic USH contributor gene [26], and CEP250 as an atypical USH gene [27]. Among these genes, HARS is debatable as an USH3 gene, because patients carrying mutations in this gene develop episodic psychosis as well as progressive hearing loss and RP [25], which could be clinical symptoms of other rare syndromes. The atypical USH patients carrying the homozygous CEP250 nonsense mutation exhibit early-onset hearing loss and mild RP. They all have a heterozygous C2orf71 nonsense mutation. Although C2orf71is an autosomal recessive RP gene [43–46], it is unclear whether its heterozygous mutation also contributes to the disease development of these atypical USH patients.

Table 1.

USH loci and genes with predicted protein function.

| USH type | Locus | gene name | Protein name | Predicted function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USH1 | USH1B | MYO7A | myosin VIIa | Actin-based motor protein | [28] |

| USH1C | USH1C | harmonin | PDZ scaffold protein | [29, 30] | |

| USH1D | CDH23 | cadherin 23 | Cell adhesion | [31, 32] | |

| USH1E | n/a | n/a | Unknown | [212] | |

| USH1F | PCDH15 | protocadherin 15 | Cell adhesion | [33, 34] | |

| USH1G | USH1G | SANS | Scaffold protein | [35] | |

| USH1H | n/a | n/a | Unknown | [213] | |

| USH1J | CIB2 | CIB2 | Ca2+ and integrin binding | [36] | |

| USH1K | n/a | n/a | Unknown | [214] | |

| USH2 | USH2A | USH2A | usherin | Cell adhesion | [37] |

| USH2C | GPR98 | VLGR1 (aka GPR98, MASS1) | G-protein coupled receptor | [38] | |

| USH2D | DFNB31 (Whrn in mice) | whirlin | PDZ scaffold protein | [39] | |

| USH3 | USH3A | CLRN1 | Clarin-1 | Auxiliary subunit of ion channels? | [40–42] |

| n/a | n/a | PDZD7 | PDZD7 | PDZ scaffold protein | [26] |

In addition to involvement in USH, different mutations in nine USH genes have been reported to cause other discrete diseases (Table 2). For example, different mutations in MYO7A are the causes of USH1, nonsyndromic recessive deafness 2 (DFNB2), nonsyndromic dominant deafness 11 (DFNA11) and atypical USH [47–51]. Other examples include mutations in USH1C, CDH23, PCDH15, CIB2 and DFNB31, which lead to either USH or nonsyndromic recessive deafness (DFNB) [32, 36, 39, 52–58], mutations in USH2A which have been found in patients with either USH2 or nonsyndromic RP [37, 59] and mutations in GPR98 which are responsible for either USH2 or seizures [38, 60]. For at least four USH1 genes, MYO7A, CDH23, PCDH15 and USH1C, there appears to be a genotype-phenotype correlation in patients [50, 54]. Nonsense, frameshift and splice site mutations resulting in truncation of USH1 proteins are usually responsible for the occurrence of USH1, while ‘leaky’ splice site and some missense mutations lead only to DFNB. It is hypothesized that mutant alleles causing DFNB and USH1 are hypomorphic and functionally null alleles, respectively, and that residual function of USH1 proteins from the DFNB alleles spare normal retinal and vestibular functions in patients [50, 54, 61]. Additionally, most USH genes have multiple splice isoforms with different spatial and temporal expression patterns in the inner ear and retina [29, 62–68]. These USH splice isoforms could have slightly different cellular functions. Thus, the differential disruption of USH splice isoforms due to mutations in different USH gene regions may also contribute to the genotype-phenotype correlation found in patients [53].

Table 2.

Different diseases caused by USH gene mutations.

| Gene name | USH subtype | Other diseases involved | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myo7a | USH1B | DFNB2, DFNA11, atypical USH | [47–51] |

| USH1C | USH1C | DFNB18 | [52, 53] |

| CDH23 | USH1D | DFNB12 | [32, 54, 55] |

| PCDH15 | USH1F | DFNB23 | [56, 57] |

| CIB2 | USH1J | DFNB48 | [36] |

| USH2A | USH2A | Nonsyndromic RP | [37, 59] |

| GPR98 | USH2C | Febrile and afebrile seizures | [38, 60] |

| DFNB31 | USH2D | DFNB31 | [39, 58] |

| PDZD7 | Digenic USH | DFNB | [26, 215] |

DFNB: nonsyndromic recessive deafness

DFNA: nonsyndromic dominant deafness

3. Expression of USH genes

USH genes are expressed in various tissues [69–74]. This section addresses their protein expressions in the inner ear and retina (Table 3).

Table 3.

USH protein distributions in hair cells and photoreceptors.

| Protein name | Subcellular distribution | References |

|---|---|---|

| Hair cells | ||

| Myosin VIIa | Cytoplasm and stereocilia | [86–90] |

| Harmonin | UTLDa and synapse | [84, 85, 90, 99, 104] |

| Cadherin 23 | Transient lateral link, kinociliary link, tip link and synapse | [79–82, 90, 101, 103] |

| Protocadherin 15 | Transient lateral link, kinociliary link, tip link and synapse | [63, 79, 83, 90, 102, 103] |

| SANS | UTLDa and stereociliary tip | [86, 139] |

| CIB2 | stereocilia | [36] |

| Usherin | Ankle link and synapse | [68, 77, 99, 100] |

| VLGR1 | Ankle link and synapse | [77, 93, 99, 100, 102, 103] |

| Whirlin | Ankle link, stereociliary tip and synapse | [66, 68, 77, 94–96, 100] |

| Clarin-1 | hair bundle, apical cytoplasm and synapse | [97, 98] |

| PDZD7 | Ankle link | [68, 94] |

| Photoreceptors | ||

| Myosin VIIa | Connecting cilium, periciliary membrane, calyceal process and synapse | [19, 20, 105, 109, 112] |

| Harmonin | Outer segment, calyceal process and synapse | [19, 99, 105, 112, 113] |

| Cadherin 23 | Inner segment, calyceal process and synapse | [19, 105, 112] |

| Protocadherin 15 | Base of outer segment, calyceal process and synapse | [19, 105, 112] |

| SANS | Connecting cilium, basal body, calyceal process and synapse | [105, 111, 133] |

| CIB2 | Inner and outer segment | [36] |

| Usherin | Periciliary membrane complex and synapse | [17, 19, 68, 99, 100, 105, 106, 116, 117] |

| VLGR1 | Periciliary membrane complex and synapse | [19, 68, 99, 100, 105, 106, 117] |

| Whirlin | Periciliary membrane complex | [17, 68, 100, 105, 106, 111, 117] |

| Clarin-1 | Connecting cilium, inner segment, adherens junction and synapse | [97, 118] |

| PDZD7 | unclear | [26, 68] |

UTLD: upper tip link density

3.1. USH proteins are mainly localized to the hair bundle and synapse of inner ear hair cells

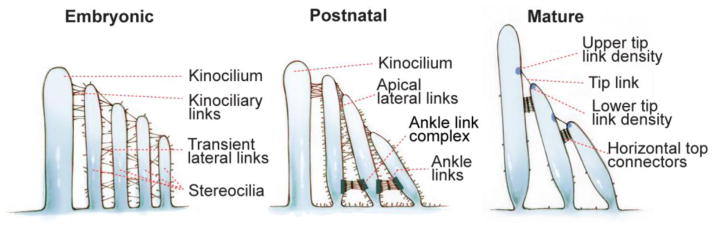

Various dynamically-changing proteinaceous filamentous links (Figure 3) exist in hair cell bundles, where USH proteins are localized. These interstereociliary links are essential for bundle development, maintenance and function [75–77]. During early development, kinociliary links connect the kinocilium to its neighboring stereocilia, and transient lateral links connect adjacent stereocilia along their entire length [75, 76]. Later, ankle links and tip links emerge at the stereociliary base and tip, respectively [76]. Tip links connect the tip of shorter stereocilia to the lateral wall of taller stereocilia (Figures 1D and 3) and mediate gate opening of ion channels during MET (Figure 1E). Electron dense structures, upper (UTLD) and lower (LTLD) tip link densities (Figure 3), are observed at the upper and lower insertion sites of tip links in stereocilia, respectively. Kinociliary links, transient lateral links and ankle links disappear after maturation of mammalian cochlear hair cells, but some are permanent in the vestibular system [75, 76]. Tip links remain in mature cochlear and vestibular hair cells throughout life [78, 79].

Figure 3.

Dynamic changes of various interstereociliary links in the hair bundle during and after development. During embryogenesis, emerging stereocilia are bundled by transient lateral links and connected with the kinocilium through kinociliary links. Postnatally, the transient lateral links are gradually replaced by tip links, apical lateral links and ankle links. After maturation, the apical lateral links are replaced by horizontal top connectors. Upper tip link density (UTLD) and lower tip link density (LTLD) are electron-dense structures at the insertion sites of tip links in the taller and shorter stereocilia, respectively. In mature rodent cochlear hair cells, the ankle links, kinociliary links and kinocilium disappear.

Among USH1 proteins, cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 are localized to transient lateral links and kinociliary links during development and to tip links in adulthood [63, 80–83]. Harmonin and SANS are part of the UTLD [84–86]. CIB2 was found in both hair cells and supporting cells [36]. In hair cells, CIB2 is localized along stereocilia and more concentrated near the tip. Myosin VIIa is distributed throughout hair cells including the cytoplasm and hair bundle [87–89]. This protein has been shown to be at the tip, base, shaft or entire length of stereocilia by different research laboratories [86, 87, 90–92]. These inconsistent myosin VIIa signal patterns may result from 1) different detection approaches, such as immunostaining of the endogenous protein or overexpression of a tagged exogenous protein; 2) different myosin VIIa antibodies, which could have variable quality and/or detect different myosin VIIa isoforms; 3) different hair cell types, such as the cochlear IHCs, OHCs or vestibular hair cells, examined at different developing time points; and 4) various sample processing procedures.

The protein of the USH2 gene GPR98, VLGR1 (very large G protein-coupled receptor 1), has been shown to be a major component of ankle links [77, 93]. Other USH2 proteins usherin and whirlin (DFNB31), together with PDZD7, are colocalized with VLGR1 at the ankle link complex [68, 77, 93, 94]. Additionally, whirlin is also present at the stereociliary tip [66, 95, 96]. Among USH3 proteins, clarin-1 is relatively well studied in the inner ear. While clarin-1 could not be found in the hair bundle of zebrafish mechanosensory hair cells [97], its presence in mouse cochlear hair bundles was suggested [98].

USH proteins are also found in the synapse of hair cells, where the electrical responses generated from MET are transmitted to second-order neurons in the inner ear. Protocadherin 15, cadherin 23, harmonin, clarin-1, usherin, VLGR1 and whirlin have all been reported in the synapses of developing and mature hair cells [97, 99–104].

3.2. USH proteins are localized in photoreceptors and other retinal cell types

Cellular distributions of USH proteins in the retina are less well-defined, owing to inconsistent reports in the literature. These inconsistent reports might result from different antibodies, different sample processing procedures and/or different species used in the studies. In general, USH proteins have been localized in photoreceptors and some other retinal cells, and may have distinct distribution patterns in retinas of different species. In photoreceptors, they tend to be positioned to some specific subcellular structures (Table 3).

One such structure is the calyceal process of long actin-based, microvilli-like thin projection (Figure 2C). Calyceal processes extend from the inner segment apex toward the outer segment, and wrap tightly around the basolateral outer segment. Calyceal processes exist in primate, amphibian and avian photoreceptors, but are absent and vestigial in rodent rods and cones, respectively [105]. Although differing in function, calyceal processes and the outer segment of photoreceptors are considered structurally similar to stereocilia and the kinocilium of hair cells. Another structure related to USH proteins is the periciliary membrane complex in mammalian photoreceptors (Figure 2C), which is a specialized plasma membrane region at the inner segment apex facing the connecting cilium. The periciliary membrane complex is thought to be analogous to the periciliary ridge complex [106], which likely participates in protein trafficking between frog photoreceptor inner and outer segments [107].

In mice, USH1 protein myosin VIIa exists mostly in RPE cells [89, 108]. Its localization in photoreceptors at the connecting cilium and periciliary membrane remains open to debate [20, 109, 110]. Other USH1 proteins were localized to various photoreceptor compartments, including the outer segment, connecting cilium, inner segment and synapse [36, 56, 99, 111–113]. Some of these findings are inconsistent among different research groups [99, 105, 113]. Apart from photoreceptors, CIB2 was found in RPE and other retinal cells [36]. Recently, Sahly et al. reported that USH1 proteins, except CIB2 (not examined), are all located at calyceal processes of human, monkey and frog photoreceptors [105]. The USH1 protein localization in photoreceptor calyceal processes, to some extent, corresponds with their localization in hair cell stereocilia. Additionally, studies in zebrafish illustrate that cadherin 23 and harmonin are localized in a small subset of GABAergic amacrine cells and Müller cells, respectively [114, 115]. In summary, USH1 proteins may have variable cellular and subcellular distributions in retinas of different species.

USH2 proteins usherin, VLGR1 and whirlin were initially positioned in the inner segment, connecting cilium, basal bodies, synaptic terminus and adherens junction of mouse photoreceptors [17, 19, 100, 111]. Using antibodies whose specificities have been verified stringently, the three USH2 proteins are now localized to the periciliary membrane/ridge complex of mouse and frog photoreceptors [106, 116, 117]. USH2 protein localizations at the periciliary membrane complex were further confirmed in monkey photoreceptors [105].

Distribution of USH3 protein clarin-1 in the retina has been reported by three research groups and remains inconclusive [97, 118, 119]. In mouse retinas, one group showed that clarin-1 protein is present in the photoreceptor connecting cilium, inner segment and synaptic terminus [118], whereas others demonstrated that clarin-1 mRNA exists only during development in Müller cells but not photoreceptors [119]. In zebrafish retinas, Phillips et al. found that the clarin-1 protein is distributed in photoreceptors and other retinal cells, which could be amacrine cells, Müller cells and ganglion cells, during development and adulthood; in photoreceptors, clarin-1 is localized to the inner segment lateral membrane, adherens junctions with Müller cells and synaptic terminus [97].

4. USH proteins exist in multiprotein complexes

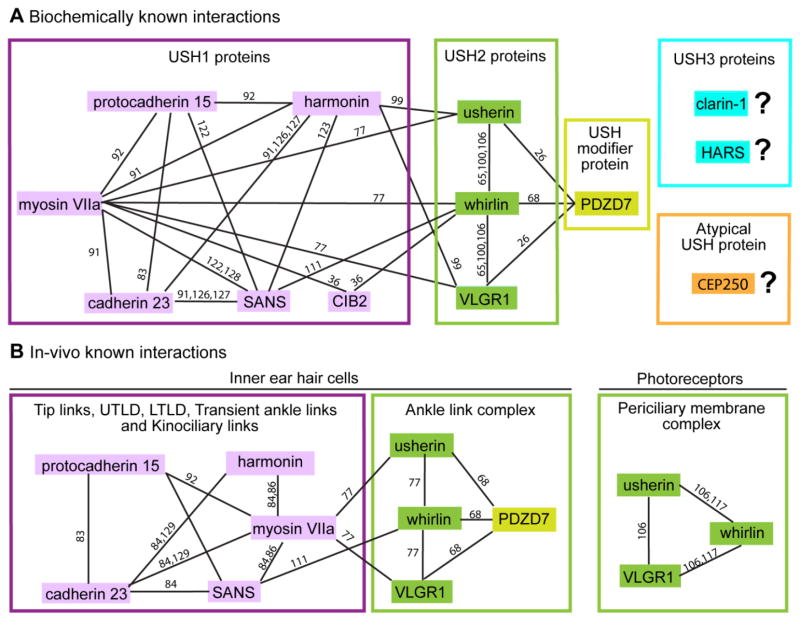

Individual USH proteins are predicted to accomplish various functions including actin-based intracellular trafficking, cell adhesion, scaffolds in multiprotein complexes, and G protein- or Ca2+-mediated signaling (Table 1). For example, myosin VIIa is revealed as an unconventional motor protein with a motor domain, actin-binding domain and long tail region [120, 121]. Harmonin, whirlin and PDZD7 are paralogs belonging to the same protein family. These three proteins and SANS each have several protein-protein interaction domains and thus are thought to be scaffold proteins [18, 68, 99, 106, 117, 122, 123]. Cadherin 23, protocadherin 15 and usherin are transmembrane proteins with a long extracellular region containing various cell adhesion domains, suggesting a potential function of binding cell surface proteins and/or extracellular matrix proteins [79, 83, 124]. CIB2 has several Ca2+-binding EF-hand domains and is able to bind to integrin [36], while VLGR1 is a very large adhesion G protein-coupled receptor with multiple extracellular Ca2+-binding motifs [70]. Recent colocalization, in vitro interaction and mouse genetic studies on USH proteins suggest that proteins within the same USH clinical type interact to form multiprotein complexes (Figure 4) and that mutations in USH genes lead to protein complex disruption and disease development [18, 77, 90, 106]. Therefore, the distinct functions of individual USH proteins probably contribute to the function of USH multiprotein complexes as a whole in various subcellular regions of hair cells and photoreceptors [17–19, 21, 22, 125]. Here, we present one USH1 complex and one USH2 complex to exemplify USH multiprotein complexes.

Figure 4.

Known interaction networks among USH proteins. (A) Interactions among USH1 (pink), USH2 (green) and PDZD7 proteins found and confirmed by various in vitro biochemical assays. Interactions among the two USH3 (blue), atypical USH (CEP250) and other USH proteins have not yet been revealed. (B) Interactions of USH proteins confirmed in inner ear hair cells (left) and photoreceptors (right) by genetic studies. Reference numbers are given along each line.

USH1 proteins harmonin, SANS and myosin VIIa are suggested to form a complex (Figure 4) at the UTLD in mature inner ear hair cells by several lines of evidence. Genetic and cell biological studies have revealed interdependence of these proteins for their normal localizations at the UTLD in mice [84, 86]. Structural and biochemical studies further show that harmonin and SANS, the two scaffold proteins, form a complex through the harmonin PDZ1 domain and SANS SAM region and PDZ-binding motif (PBM) [123]. The harmonin N-domain in the harmonin/SANS complex is open and available to interact with the cadherin 23 short cytoplasmic region [91, 126, 127], and the CEN domain of SANS is able to bind to the FERM and MyTH4 domains of myosin VIIa [122, 128]. Thus, the USH1 complex of harmonin, SANS and myosin VIIa is thought to anchor the cadherin 23 component of tip links to actin filaments inside taller stereocilia [84]. Latest studies in zebrafish hair cells also found that cadherin 23, myosin VIIa and harmonin are likely preassembled into a complex at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where the proteins are synthesized [129]. Defects in any of the three proteins affect trafficking of the complex to hair bundles and induce ER stress and apoptosis in hair cells [129].

USH2 proteins usherin, VLGR1 and whirlin are able to interact in vitro through PDZ domains of whirlin and PBMs of usherin and VLGR1 (Figure 4) [65, 100, 106]. They are colocalized at the photoreceptor periciliary membrane complex (Figure 2C) [105, 106, 111, 116, 117] and the developing hair cell ankle link complex (Figure 3) [65, 77, 93]. Loss of one USH2 protein affects the normal localizations of other USH2 proteins in photoreceptors [106] and hair cells ([77] and our unpublished data), and whirlin is able to recruit usherin and VLGR1 to the photoreceptor periciliary membrane complex [117]. These findings indicate that USH2 proteins exist as a multiprotein complex in vivo. USH modifier protein PDZD7 also interacts directly with the three USH2 proteins (Figure 4) [26, 68] and colocalizes with VLGR1 and whirlin at the hair cell ankle link complex [68, 94]. PDZD7 and the three USH2 proteins are mutually dependent for normal localizations in cochlear hair cells [68, 77]. However, localization of PDZD7 at the photoreceptor periciliary membrane complex could not be determined [26, 68]. Ablation of PDZD7 did not affect the integrity of the USH2 complex in mouse photoreceptors [68]. Therefore, PDZD7 is probably a component of the USH2 multiprotein complex in hair cells but not photoreceptors. Currently, three-dimensional structural data of the USH2 multiprotein complex are unavailable.

Linkage between USH1 and USH2 multiprotein complexes appears likely (Figure 4). For instance, USH1 protein CIB2 was shown to be capable of binding to both USH1 protein myosin VIIa and USH2 protein whirlin in vitro [36]. Another in vitro biochemical study demonstrated molecular interactions between USH1 scaffold protein harmonin and USH2 proteins usherin and VLGR1 [99]. Therefore, USH proteins are currently thought to function cooperatively in vivo through the intertwined network of their multiprotein complexes. However, it is still elusive as to how these multiprotein complexes coordinate functionally at their distinct subcellular locations, although association among USH multiprotein complexes could occur transiently during trafficking from the ER to final destinations.

To thoroughly understand the biological functions of various USH multiprotein complexes, extensive efforts have been implemented to identify novel partners that interact with known USH proteins, mainly through yeast two-hybrid screen, in vitro biochemical confirmation and in vivo immunolocalization. Espin 1–3 isoforms, derived from alternative usage of transcriptional start sites and alternative splicing, were discovered to associate with the USH2 protein complex [74]. Espins bind to actin monomers and bundle actin filaments [130]. They colocalize partially with whirlin at the photoreceptor periciliary membrane and hair cell ankle link complexes. Interaction between espins and whirlin in vivo appears important for the maintenance of actin bundle geometry [74]. Other recent findings describe interactions of myomegalin with the SANS CEN domain [131], SPAG5 (sperm-associated antigen 5, also called astrin) with the usherin cytoplasmic region [132], and Magi2 (membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted-2) with the SANS SAM region [133]. However, caution is needed when data from screens of USH protein-interacting partners are interpreted physiologically, because some of the interactions have not been confirmed in vivo [134, 135].

5. Functional studies of USH gene products

5.1. USH genes in inner ear hair cells

5.1.1. USH1 genes

Mice and zebrafish carrying mutations in USH1 gene orthologs, except CIB2 (not reported yet), share common morphological phenotypes of their hair bundles [81, 90, 115, 136, 137]. Cdh23v2J/v2J, Pcdh15av3J/av3J, Ush1gjs/js, Myo7a4626SB/4626SB and Ush1c−/− mice have fragmented hair bundles with planar cell polarity defects in both IHCs and OHCs [90], which are similar to the hair bundle phenotypes found in myo7a, cdh23, pcdh15 and ush1c mutant zebrafish [81, 115, 136, 137]. Such morphological defects caused by USH1 gene mutations could result from disconnection between the kinocilium and neighboring stereocilia, and among stereocilia themselves. Therefore, proteins encoded by USH1 genes probably function cooperatively in maintaining cohesion of stereocilia and kinocilium in developing and mature hair bundles as components of tip links, UTLD and other interstereociliary links.

Stereociliary tip links are absent in Cdh23v2J/v2J, Pcdh15av3J/av3J and Ush1g−/− mice [138, 139] and in cdh23tc317e/tc317e, cdh23tc300a/tc300a and cdh23tc370e/tc370e zebrafish [81]. Consistently, various MET abnormalities have been reported in Cdh23, Pcdh15, Myo7a, Ush1c and Ush1g mutant mice (Table 4), which were recorded in vitro by either fluid jet or stiff glass probe stimulation. Among these USH1 mutant mice, Ush1gfl/flMyo15-cre+/− mice have intact hair bundle morphology. Thus, abnormal MET responses detected in USH1 mutant mice are probably primary and not secondary to bundle morphological defects. Knockdown of cib2 in zebrafish causes reduced microphonic potentials of neuromasts, suggesting that CIB2, like other USH1 proteins, is also essential for MET responses in hair cells [36]. Therefore, USH1 proteins are either directly or indirectly involved in the MET process in the hair cell bundle.

Table 4.

MET defects in USH1 mutant mice.

| Mouse | MET defects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cdh23v2J/v2J | Reduced current and abnormal directional sensitivity | [138] |

| Pcdh15av3J/av3J | Reduced or no current and abnormal directional sensitivitya | [92, 138] |

| Pcdh15av6J/av6J | Reduced current and abnormal directional sensitivitya | [138] |

| Myo7a6J/6J | Increased current, decreased sensitivity and abnormal adaptation | [216] |

| Myo7a4626SB/4626SB | Increased current, decreased sensitivity and abnormal adaptation | [216] |

| Ush1cdfcr/dfcr | Decreased sensitivity of OHCsa | [84] |

| Ush1cdfcr-2J/dfcr-2J | Reduced OHC current and abnormal adaptation of outer and vestibular hair cellsa | [85] |

| USH1gfl/fl;Myo15-Cre+/− | Reduced current and normal sensitivity | [139] |

The discrepancy of MET defects found in USH1 mice carrying different mutant alleles of the same gene could result from differences in splice isoforms affected and/or conditions used for MET measurements, such as either fluid jet or stiff glass probe stimulation.

Harmonin has also been found in synaptic termini of mouse, rat and zebrafish hair cells [99, 104, 115]. In mature cochlear IHC synapses, harmonin interacts with the cytoplasmic terminus of Cav1.3 α1 subunit, the pore-forming subunit of voltage-gated Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels, which is essential for Ca2+-dependent glutamate release and synaptic transmission. Harmonin controls the amount of Cav1.3 α1 on the synaptic plasma membrane by increasing ubiquitination of Cav1.3 α1 subunit, improves voltage-dependent facilitation of Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels, and regulates exocytosis of vesicles containing readily releasable neurotransmitters at synaptic ribbons [104, 140].

5.1.2. USH2 genes

Most mouse models carrying USH2 gene mutations share common phenotypes. In Gpr98−/− and Gpr98del7TM/del7TM mice, ankle links are completely missing, indicating that VLGR1 is a core protein of ankle links [77, 93]. In all reported Gpr98, Ush2a, Whrn (mouse ortholog of DFNB31) and Pdzd7 mutant mice, except Whrnwi/wi mice [58, 141], abnormal stereociliary organization was observed in OHC but not IHC bundles [68, 77, 93, 106, 116, 142, 143]. Consistently, Gpr98−/−, Gpr98del7TM/del7TM and Pdzd7−/− mice have reduced MET amplitude and sensitivity in OHCs, but normal MET responses in IHCs [68, 77, 93]. USH2 mutant mice, except Whrnwi/wi mice, exhibit no obvious behaviors of vestibular dysfunction. Gpr98−/−, Gpr98del7TM/del7TM and Pdzd7−/− vestibular hair cells also have normal MET responses [68, 77, 93]. These findings indicate that USH2 proteins at the ankle link complex are important for organizing stereocilia into a V-shaped bundle during OHC development and raise a possibility that neither USH2 proteins nor the ankle link complex may function significantly in IHCs or vestibular hair cells.

By contrast, Whrnwi/wi mice show shortened stereocilia in both IHCs and OHCs as well as disorganized OHC bundles [58, 141, 144]. The mice have circling and head tossing phenotypes, indicative of vestibular dysfunction. It is currently hypothesized that the more severe phenotypes found in Whrnwi/wi mice are probably due to the combined defective Whrn expressions at both the tip and ankle link complex of stereocilia [106, 141]. However, the OHC MET in Whrnwi/wi mice has been found to be normal [145].

5.1.3. USH3 genes

Similar to most USH2 mutant mice, Clrn1−/− mice show morphological defects of OHC but not IHC bundles [146], and they have reduced MET amplitude and sensitivity in OHCs but normal MET responses in IHCs [98] during development. However, unlike most USH2 mutant mice, Clrn1−/− mice exhibit progressive vestibular dysfunction with no overt circling or head tossing behaviors by one month of age but severe circling and head tossing behaviors by 6 months of age [146]. Additionally, MET responses in Clrn1−/− vestibular hair cells show reduced currents and less sensitivity [98]. Consequently, USH2 and USH3 proteins might participate in similar cellular processes of stereocilia organization in the cochlea, but play relatively distinct roles in the vestibular system during bundle development.

5.1.4. In summary

Proteins encoded by most USH genes, as various interstereociliary links, confer cohesive organization of stereocilia during bundle growth and differentiation. Some USH proteins remain functional in adult hair cells at important subcellular structures, e.g., tip links and tip link densities. The bundle morphological defects caused by USH gene mutations may affect establishment of the MET process, which is likely causal for hearing loss and, sometimes, vestibular areflexia. Thus, USH proteins are required for development, maintenance and function of inner ear hair cell bundles. Some USH proteins may additionally serve a synaptic transmission role from hair cells to downstream neurons.

5.2. USH genes in the retina

Current understanding of USH genes affecting retina health is fragmentary. The only relatively well-understood USH gene in the retina is MYO7A. Myosin VIIa in RPE cells is implicated in driving melanosomes into apical processes [147], delivering phagosomes to their cytoplasmic digestion site from apical processes [148], and translocating RPE65, an enzyme important for visual pigment regeneration [149]. In photoreceptors, delay of rhodopsin transport to the outer segment is shown in three different strains of Myo7a mutant mice and myo7aaty229d/ty229d zebrafish (Zebrafish has two human MYO7A orthologs, myo7aa and myo7ab.) [150, 151]. The role of myosin VIIa in rhodopsin transport is proposed to be achieved through direct interaction of myosin VIIa with spectrin-βV, an adaptor protein associating with rhodopsin, kinesin-II and the dynein complex [152]. Further, Myo7ash1-11J/sh1-11J mice have a delay and increased threshold of transducin translocation from the outer to inner segment upon light stimulation [153]. Together, these findings suggest that myosin VIIa is important for protein and organelle transport in both RPE cells and photoreceptors of the retina.

Physiological and histological studies in various Myo7a mutant mouse and myo7aa mutant zebrafish retinas produced somewhat inconsistent results, possibly resulting from different mutant species and strains, genetic backgrounds, retinal pigmentation levels and light illumination levels used in the experiments [149, 151, 153–155]. Electroretinogram (ERG) recording is a non-invasive technique to measure retinal electrical responses to light stimuli with resulting a- and b-waves representing responses from photoreceptors and inner retinal neurons, respectively. Myo7a4626SB/4626SB, Myo7a816SB/816SB, Myo7a7J/7J, Myo7a8J/8J and Myo7a9J/9J mice and myo7aaty229d/ty229d mutant zebrafish exhibit reduced ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes but normal light sensitivity [151, 155], while albino Myo7a4626SB/4626SB mice show an age-dependent reduction of ERG b-wave, less light sensitivity and slow recovery from light desensitization [154]. In myo7aaty229d/ty229d zebrafish, mild retinal degeneration, indicated by photoreceptor loss, was observed at 10 days postfertilization [151], while no retinal degeneration occurs in all Myo7a mutant mice examined under normal husbandry conditions. Light illumination can induce retinal degeneration in Myo7ash1-11J/sh1-11J [153] but not Myo7a4626SB/4626SB mice [149]. Although inconsistently observed by different research groups, most physiological and histological abnormalities can be rescued by delivery of Myo7a cDNAs into RPE and photoreceptor cells of Myo7a mutant mice using either adeno-associated virus (AAV) or lentivirus [154, 156–159], suggesting that the above identified phenotypes are specific to Myo7a mutations.

The second well-studied USH genes in the retina are the group of USH2 genes. In Ush2a−/−, Gpr98del7TM/del7TM and Whrnneo/neo mice, the integrity of the USH2 complex is disrupted at the photoreceptor periciliary membrane complex [106]. Ush2a−/− and Whrnneo/neo mice exhibit late-onset weak retinal degeneration [106, 116]. Consistently, knockdown of ush2a and gpr98 in zebrafish results in an increase of dying photoreceptors [26]. Therefore, the USH2 complex is important for photoreceptor survival. However, the exact biological function of the USH2 complex in photoreceptors remains elusive. Originally, the USH2 complex at the periciliary membrane complex was proposed to participate in protein trafficking through the connecting cilium [107], but no clear evidence demonstrates any defects in protein trafficking between the inner and outer segment in Ush2a−/− and Whrnneo/neo photoreceptors [106, 116]. Interestingly, using Whrnwi/wi mice, which do not develop spontaneous retinal degeneration [106], Tian et al. demonstrated a defect in light-induced transducin translocation from photoreceptor outer to inner segment and light-induced retinal degeneration [160]. The molecular mechanisms underlying these phenotypes in Whrnwi/wi mice need to be further elucidated.

Among all reported USH1 and USH3 mouse models, the Ush1c knock-in mouse is the only one to have a spontaneous retinal degeneration phenotype [161], mimicking the RP symptoms of USH1 patients. In this knock-in mouse, a c.216G>A cryptic splice site mutation in USH1C, cloned from Acadian USH1 patients in Louisiana, was inserted into the mouse genome to replace the normal mouse Ush1c sequence [162]. It has been proposed that gain-of-function or dominant-negative effect of a truncated harmonin protein fragment from aberrant splicing account for the degeneration. Additionally, ush1cfh293/fh293 zebrafish line was recently found to have progressive retinal degeneration through labeling of apoptotic marker caspase-3 [115]. Despite these findings, the function of harmonin in the retina remains unidentified.

In summary, little is known of USH protein function in the retina, except myosin VIIa. One of the reasons is that mouse models with mutant USH genes typically have no or weak retinal phenotypes and thus provide limited insight.

5.3. USH genes in other tissues

Three patients from two unrelated Arabic consanguineous families were found to have profound congenital deafness and enteropathy caused by a deletion in the USH1C gene [30], suggesting that USH1C may have a function in the intestine in addition to the inner ear and retina. Harmonin was recently localized at the tip of intestinal epithelial cell microvilli, which are structurally analogous to hair cell stereocilia [69]. At this place, harmonin is able to anchor protocadherin 24, mucin-like protocadherin and myosin VIIb through direct interactions. In Ush1c−/− mice, altered morphology and complete disappearance of microvilli were found in 10 – 40% of epithelial cells of the small intestine and proximal colon, suggesting an important role of harmonin in maintaining the structure of intestinal enterocytes. Even so, the intestinal physiology of Ush1c−/− mice appears normal [69], indicating a potential high tolerance of the intestine to loss of harmonin, which may explain the absence of enteropathy in most patients carrying USH1C mutations.

Whirlin protein has been localized in various neurons in the rat cerebrum, cerebellum and thalamus [73] in addition to hair cells and photoreceptors. This protein is required for maintenance of paranodal organization and prevention of subcellular organelle accumulation in myelinated axons of the central and peripheral nervous systems [163]. Another study involving a large-scale phenotyping screen unexpectedly discovered a defective nociceptive response in Whrntm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi mutant mice [164]. Female Whrntm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi mutant mice at 10 weeks of age and fed on a high fat diet were able to stay on a 52°C hot plate longer than controls, indicating that whirlin may be involved in thermal pain perception. In Drosophila, the closest homolog of DFNB31, dysc (dyschronic), was recently identified as a novel component of the circadian output pathway [165]. DYSC protein is present in the major neuronal tracks throughout the fly central brain. It probably functions through forming a complex with a calcium-activated potassium channel SLOWPOKE and regulating the expression of this channel. Several dysc mutants generated by the P-element insertions have normal central circadian machinery, but exhibit an arrhythmic locomotor behavior. These findings indicate a potential role of whirlin in regulation of circadian rhythm in the brain. DFNB31 is known to have multiple alternatively-spliced isoforms, whirlin long and short isoforms [58, 166]. Whirlin long isoforms are predicted to be disrupted in all the mutant mice and flies used in the above studies. Therefore, the potential whirlin functions in the brain are probably attributed to whirlin long isoforms.

USH2A was shown to be associated with touch sensitivity and acuity. Studies on two cohorts of USH patients from Germany and Spain have revealed that the tactile acuity and vibration detection threshold are compromised in patients carrying pathogenic USH2A mutations, but not in other USH2 patients [167]. Furthermore, patients with USH2A mutations in the study were found to have a slightly but significantly lower heat pain threshold. Therefore, the USH2A and DFNB31 genes seem to be in the same neuronal sensory pathway as in vision and hearing, although the effects of the two genes on the heat pain threshold appear opposite. However, due to the small sample sizes in the two studies [164, 167], involvement of the DFNB31 and USH2A genes in the thermal pain perception needs to be further verified, and the underlying mechanisms need to be elucidated.

Before its discovery as the USH2C gene [38], GPR98 and its ortholog were originally identified as a causative gene for febrile and afebrile seizures in humans [60] and for audiogenic epilepsy in mice [168]. GPR98 ortholog mRNAs were detected in the mouse and zebrafish brains [67, 169]. VLGR1 protein is highly enriched in the mouse midbrain superior and inferior colliculi [70], while inferior colliculus is known to participate in the occurrence of audiogenic seizures [170]. In oligodendrocytes of the mouse superior and inferior colliculi, VLGR1 regulates the stability of myelin-associated glycoprotein [70], a protein functioning in the axon-glial interaction at the periaxonal membrane of glial myelin sheaths [171]. As mentioned, whirlin is involved in the paranodal organization between the glial myelin sheaths and their wrapped axons [163]. Therefore, both VLGR1 and whirlin likely play a role in nerve axon myelination in the brain.

6. Insights from current literatures about USH genes in various tissues

USH proteins are generally localized to folded plasma membrane structures. For example, USH1 proteins are present at inner ear hair cell stereocilia (Figure 3) [36, 79, 80, 82–86, 90, 139], retinal photoreceptor calyceal processes (Figure 2C) [105] and intestinal enterocyte microvilli [69]. USH2 proteins are present at the ankle link complex of the hair cell stereociliary base (Figure 3) [68, 77, 93, 94] and the periciliary membrane complex of the photoreceptor inner segment apex facing the connecting cilium (Figure 2C) [68, 105, 106, 116]. In the nervous system, although the exact cellular or subcellular localizations of whirlin and VLGR1 in myelinated nerves are unclear [70, 163], it is possible that these two proteins are present in the myelin sheath, layers of the folded plasma membrane of oligodendrocytes or Schwann cells, to fulfill their functions. The folded plasma membrane structures, where USH proteins are localized, are likely highly dynamic. For example, the plasma membrane of hair cell stereocilia probably moves toward the tip when stereocilia grow rapidly during development; the plasma membrane of the photoreceptor connecting cilium and outer segment probably moves distally during outer segment renewal. Considering the cell adhesion, Ca2+-binding and cell signaling domains predicted in several USH proteins and the localizations of most USH proteins on or near the plasma membrane, USH proteins may mediate signaling to regulate and maintain the dynamic organization of folded membranous structures.

USH proteins are believed to be assembled in multiprotein complexes with other USH and non-USH proteins. As scaffold proteins, harmonin, SANS, whirlin and PDZD7 are essential for organization of these multiprotein complexes. These scaffold proteins bind to their partners mostly through PDZ domains and PBMs with weak affinities in the micromolar range [172]. Therefore, interactions in USH multiprotein complexes are probably transient, consistent with the signaling and dynamic cell adhesion roles of these complexes. PDZ domain-mediated interactions are promiscuous [172]. Their specificity is usually regulated in spatial, temporal and cell type-specific manners. This may explain that the composition and organization of USH multiprotein complexes vary according to tissue. Compared with the harmonin-containing USH1 protein complex at the UTLD in hair cells [91, 122, 123, 126–129], harmonin forms a complex with completely different proteins, protocadherin 24, mucin-like protocadherin and myosin VIIb, at the tip of microvilli in enterocytes [69]. Likewise, PDZD7 plays a crucial role in the USH2 protein complex formation in hair cells, but is dispensable for the complex formation in photoreceptors [68]. Despite the USH multiprotein complex variation in different tissues, individual USH proteins probably conduct similar functions among different complexes. VLGR1 protein was shown to sense the extracellular calcium changes and activate PKA and PKC through binding to Gαs and Gαq, respectively, in the superior and inferior colliculi [70]. This protein was also demonstrated to couple Gαi signaling in over-expressed cell cultures [173]. These signaling pathways could therefore co-exist at the VLGR1-containing USH2 protein complex in both hair cells and photoreceptors. Further, myosin VIIa transports cellular organelles and proteins in RPE cells and photoreceptors [147–151]. Thus, this protein could also participate in intracellular transport in hair cell stereocilia and cytoplasm, although myosin VIIa is generally proposed to anchor USH proteins to actin bundles in hair cell stereocilia. Based on dissimilarities of USH multiprotein complexes in various tissues and potential similarities of USH proteins in different multiprotein complexes, it is crucial to investigate USH proteins/multiprotein complexes in all tissues where present.

7. Current progress in therapeutic studies on USH

As mentioned, no cure for USH has been discovered so far. Present treatments mostly attempt to ameliorate hearing loss or retinal degeneration symptomatically. Here we describe therapeutic approaches that have been investigated with either success or promise.

7.1. Cochlear, vestibular and retinal implants

Cochlear implantation has proven to be a successful therapeutic approach for USH patients [174–176]. The majority of USH children receiving cochlear implants at their early age are able to hear open-set speech and develop oral communication skills at some level. Although enormous progress has been made in retinal prosthesis, the current implantation approach is less successful than cochlear implantation in terms of visual acuity that can be achieved [177]. Development of vestibular implants is still in its infancy [178, 179].

7.2. Application of antisense oligonucleotides (ASO)

Striking progress in rescuing hearing and vestibular function has been achieved via application of ASOs in the Ush1c knock-in mouse model [180]. Peritoneal injection of an 18-bp ASO in Ush1c knock-in mice at postnatal day 5 was able to restore vestibular function up to 9 months and hearing function up to 6 months, the two longest time points tested [180]. In this study, 15–18 bp ASOs were designed to have base sequences complementary to the patient genomic DNA region containing the USH1C 216G>A mutation. These ASOs were able to block the cryptic 5′ splice site generated by the mutation, which leads to production of a small amount of normal harmonin protein. Investigators are now evaluating the rescue effect of ASOs in the retina. This technique is currently limited to a specific class of mutations that generate cryptic splice sites.

7.3. Gene replacement therapy using viral vectors

Viral-mediated gene replacement therapy has attracted favor due to its encouraging efficacy and safety results obtained from clinical trials for an early-onset retinal degenerative disease, Leber’s congenital amaurosis, using serotype 2 AAV [181–183]. However, AAVs have a cargo packing limit of 4.7 kb while the most common causative USH1 and USH2 genes, MYO7A and USH2A, respectively, are much larger than this packing limit. Recent studies on the gene replacement therapy for USH have focused mainly on finding ways to deliver a large gene, especially MYO7A, into target retinal cells using various viral vectors.

Four strategies have been reported using AAVs [154, 157–159, 184, 185]. One is to pack the entire 7-kb human MYO7A cDNA into single AAV particles, even though this cDNA is significantly larger than the AAV packing limit [154, 157]. These oversized AAV particles are able to induce myosin VIIa protein expression in both RPE and photoreceptor cells after subretinal injection, rescue the molecular and cellular defects in these retinal cells, and improve the functional recovery of Myo7a4626SB/4626SB retinas after light desensitization [154, 157]. However, oversized single AAV vectors tend to have heterogeneous genomes, raising safety concerns during clinical application. The other three strategies entail application of dual AAV overlapping, trans-splicing and hybrid vectors [157, 158, 184, 185]. In these, N- and C-terminal halves of MYO7A cDNA, packed into two separate AAV vectors, are designed to reconnect inside target cells through homologous recombination (overlapping), trans-splicing, or both (hybrid) [158, 185]. It was found that dual AAV trans-splicing and hybrid vectors have better transduction efficiencies for both RPE and photoreceptor cells, compared with oversized single AAV and dual AAV overlapping vectors [158]. Subretinal injection of dual AAV trans-splicing and hybrid vectors in Myo7a4626SB/4626SB mice was shown to lead to robust myosin VIIa protein expression in the retina and to rescue the normal localizations of melanosome in RPE cells and rhodopsin in photoreceptors [158].

Lentiviral vectors are able to pack a transgene up to 7.5 kb long [186]. HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)- and EIAV (equine infectious anemia virus)-based lentiviral vectors are capable of delivering the MYO7A gene into mouse photoreceptors and RPE cells to provide ‘rescue’ of phenotypes in Myo7a mutant mice [156, 159]. A phase I/IIa clinical trial using the EIAV-based lentiviral vector carrying the human MYO7A gene, UshStat® (Oxford BioMedica), is being conducted by Dr. Richard Weleber’s group at the Oregon Health & Science University (http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/health/services/casey-eye/research/ushersyndrome-study.cfm). This clinical trial is still ongoing and results are yet unpublished.

7.4. Other therapeutic approaches

Translational read-through small molecule drugs for nonsense mutations and genome editing are two approaches with no necessity to pack large genes into a viral vector and no risk of mutagenesis caused by random insertion of viral vectors into the host genome. These two approaches are also able to keep intact the endogenous gene expression regulatory machinery. Translational read-through drugs can insert a random amino acid at the nonsense mutation site by changing mRNA conformation, thereby preventing translation premature stop. Among these drugs, molecules NB54 and PTC124 have been tested to suppress a nonsense mutation, p.R31X, of the USH1C gene in vivo [187]. Subretinal injection of NB54 and PTC124 is able to restore protein expression of full-length harmonin in mice. However, the amount of corrected harmonin protein relative to its endogenous protein level was not reported, and the ability of PTC124 to read through the premature stop codon was recently challenged [188]. On the other hand, genome editing is a newly emerging technique to correct gene mutations at the genomic DNA level using artificially-engineered nucleases [189–191]. Two zinc-finger nucleases, designed for different cutting sites around the p.R31X mutation of USH1C, are able to correct the DNA error through homologous recombination with a normal DNA template and eventually induce full-length harmonin protein expression without affecting cell viability in cultured cells [192]. At present, this technique is untested in the retina of animal models.

Despite these encouraging findings with translational read-through drugs and genome editing, limitations exist with both approaches. If successful in clinical trials, the translational read-through drugs can only be applied to treat patients carrying nonsense mutations in USH genes, which account for only ~12% of all USH mutations [193]. The genome editing technique has been investigated mainly to correct mutations ex vivo in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are eventually returned to the affected tissue of same patients where the iPSCs are derived [189–191]. Up to now, only two studies have attempted to edit genome in vivo by directly delivering engineered nucleases into the mouse liver [194, 195]. One showed some success in correcting the mutant gene, generating a small amount of normal protein and partially rescuing the phenotype [194]. Therefore, for future clinical application of genome editing in USH patients, direct ways to deliver engineered nucleases and DNA templates into photoreceptors and hair cells need to be explored. As genome editing is subject to off-target toxicity and low efficiency problems [189–191, 194], the mechanisms underlying genome editing need to be elucidated in detail.

8. Current gaps in understanding and treating USH

Despite identification and extensive study of USH genes using various biochemical, cellular and genetic approaches, knowledge of gene functions at the molecular level is far from full elucidation, especially in the retina, which poses a major hurdle for us to understand the pathogenic mechanisms of USH. The major reason is that phenotypes observed in retinas of USH patients are not faithfully replicated in mice, the historically gold standard animal model for studying human diseases. Several explanations were discussed previously [22, 196]. Recently, more hypotheses have been proposed. One is that human and mouse photoreceptors have different subcellular structural requirements for their survival. Localization of USH1 proteins in human photoreceptor calyceal processes [105] and the retinal degeneration symptoms manifested in USH1 patients suggest that calyceal processes are essential for human photoreceptor survival. However, the absence of real calyceal processes and unclear localizations of USH1 proteins in mouse photoreceptors implies that this structure and USH1 proteins are dispensable for rodent photoreceptor survival. Another hypothesis is that USH genes are expressed and required differently for human and animal photoreceptor survival. For instance, expressions of primate CDH23 and mouse Cdh23 isoforms are not the same in the retina [101]. Further, cadherin 23, harmonin and clarin-1 proteins of various species show significantly different retinal cellular and subcellular patterns [97, 99, 112, 114, 115, 118, 119]. A third hypothesis is that light illumination is necessary to induce retinal degeneration in USH mouse models [153, 160], although the underlying mechanism is unclear. Recently, zebrafish models carrying USH gene mutations have emerged to exhibit early retinal degeneration phenotypes, such as myo7aaty229d/ty229d and ush1cfh293/fh293 zebrafish [115, 151], indicating that zebrafish models could be useful for understanding functions of USH genes in the retina and testing potential treatments. However, evolutionary distance of zebrafish from humans and duplication of human gene orthologs may pose problems, when findings in zebrafish are interpreted and applied to humans. Therefore, development of animal models exhibiting retinal characteristics similar to USH patients is of prime importance.

Current knowledge of USH genes in the vestibular system is scarce. Direct assessment of vestibular function in humans is challenging in terms of both techniques and patients’ experience [197]. Furthermore, additional contribution of eyes and proprioceptive organs to balance maintenance [3, 198] may mask balance problems in USH patients. These factors possibly lead to research more focused on the cochlea/hearing than the vestibular system/balance. But USH1 and some USH3 patients usually experience more severe balance problems when their vision deteriorates with age. Considering the potential differences of USH multiprotein complexes across different tissues, investigation of USH genes in vestibular organs should be strengthened.

Many case reports on USH patients showing mental disorders exist in the literature [199–211]. Two recent reports also imply that usherin and whirlin may be associated with other sensory modalities, touch and pain [164, 167]. Thus, these reports raise a question whether USH patients may have other symptoms in addition to hearing, vision and balance abnormalities. However, all these reports have a limitation due to small sample sizes of patients and mice examined. Further well-designed studies to evaluate the mental health and other senses in USH patients need to be considered.

Therapeutic approaches, such as viral-mediated gene replacement, ASO therapy, translational read-through chemical drugs and genome editing, have been actively explored, while therapeutic research using various types of stem cells is relatively stagnant. Most approaches are now targeted to rescue either hearing or vision loss but not both. Except the cochlear implantation and EIAV-based lentiviral-mediated replacement of the MYO7A gene, other approaches are still in their early stage in terms of eventual application in USH patients. Finally, further investigation into the genotype-phenotype correlations of USH genes and elucidation of their molecular basis are imperative for early and appropriate diagnosis, genetic counseling, prognosis and therapy as well as for comprehensive understanding of the USH gene functions in vivo.

9. Summary

USH is an incurable autosomal recessive genetic disease. USH patients exhibit various degrees of hearing, vision and balance impairment. Currently, thirteen genes have been identified to be associated with USH. These genes encode proteins believed to conduct various cellular functions, including intracellular transport, organization of multiprotein complexes, cell adhesion and cell signaling. The USH proteins probably function in multiprotein complexes in vivo. Although required for the development, maintenance and function of hair cell stereocilia in the inner ear, USH multiprotein complexes are not well revealed at the molecular level, and understanding of disease mechanisms underlying USH is incomplete. At present, progress is being made actively to develop effective treatments for USH.

Highlights.

Review current literature concerning USH genes, their expressions and functions.

Discuss the similarities and dissimilarities of USH proteins in various tissues.

Summarize progress in the development of treatment for USH.

Describe obstacles and gaps in our understanding of USH pathobiology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank anonymous reviewers, Dr. Suzanne L. Mansour, Dr. Gary C. Schoenwolf and Dr. Jeanne M. Frederick for their manuscript critiques. The authors also thank Mr. Chris Maggio for his professional artwork. The research on Usher syndrome conducted in the authors’ laboratory has been supported by Hope for Vision, Foundation Fighting Blindness, the E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind, Inc., National Eye Institute (EY020853 and EY014800), Research to Prevent Blindness and the Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah.

Abbreviations

- USH

Usher syndrome

- USH1

Usher syndrome type 1

- USH2

Usher syndrome type 2

- USH3

Usher syndrome type 3

- RP

retinitis pigmentosa

- DFNB

nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness

- DFNA

nonsyndromic autosomal dominant deafness

- IHC

inner hair cell

- OHC

outer hair cell

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- UTLD

upper tip link density

- LTLD

lower tip link density

- MET

mechanoelectrical transduction

- ERG

electroretinogram

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- MYO7A

myosin VIIa

- USH1C

harmonin

- CDH23

cadherin 23

- PCDH15

protocadherin 15

- SANS

scaffold protein containing ankyrin repeats and sam domain

- CIB2

calcium- and integrin-binding protein 2

- USH2A

usherin

- GPR98

G protein-coupled receptor 98

- DFNB31

autosomal recessive deafness 31

- WHRN

whirlin

- CLRN1

clarin-1

- HARS

histidyl-tRNA synthetase

- PDZD7

PDZ domain containing 7

- VLGR1

very large G protein-coupled receptor 1

- SPAG5

sperm-associated antigen 5

- Magi2

membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted-2

- DYSC

dyschronic

- PDZ

PSD95/Dlg1/ZO1 domain

- PBM

PDZ-binding motif

- SAM

sterile alpha motif

- CEN

central domain

- FERM

band 4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin domain

- MyTH4

myosin tail homology 4 domain

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- iPSCs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- EIAV

equine infectious anemia virus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.LeMasurier M, Gillespie PG. Hair-cell mechanotransduction and cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2005;48:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eatock RA, Songer JE. Vestibular hair cells and afferents: two channels for head motion signals. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:501–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S, Chang R. Anatomy of the vestibular system: a review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32:437–443. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillespie PG, Muller U. Mechanotransduction by hair cells: models, molecules, and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;139:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vollrath MA, Kwan KY, Corey DP. The micromachinery of mechanotransduction in hair cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:339–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher EL, Jobling AI, Vessey KA, Luu C, Guymer RH, Baird PN. Animal models of retinal disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2011;100:211–286. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-384878-9.00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boughman JA, Vernon M, Shaver KA. Usher syndrome: definition and estimate of prevalence from two high-risk populations. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36:595–603. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keats BJ, Corey DP. The usher syndromes. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:158–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimberling WJ, Hildebrand MS, Shearer AE, Jensen ML, Halder JA, Trzupek K, Cohn ES, Weleber RG, Stone EM, Smith RJ. Frequency of Usher syndrome in two pediatric populations: Implications for genetic screening of deaf and hard of hearing children. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010;12:512–516. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e5afb8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards A, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, Grover S, Derlacki DJ. Visual acuity and visual field impairment in Usher syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:165–168. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishman GA, Bozbeyoglu S, Massof RW, Kimberling W. Natural course of visual field loss in patients with Type 2 Usher syndrome. Retina. 2007;27:601–608. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000246675.88911.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Amraoui A, Petit C. The retinal phenotype of Usher syndrome: Pathophysiological insights from animal models. C R Biol. 2014;337:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed ZM, Frolenkov GI, Riazuddin S. Usher proteins in inner ear structure and function. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45:987–989. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00135.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnet C, El-Amraoui A. Usher syndrome (sensorineural deafness and retinitis pigmentosa): pathogenesis, molecular diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:42–49. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834ef8b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosgrove D, Zallocchi M. Usher protein functions in hair cells and photoreceptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;46:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kremer H, van Wijk E, Marker T, Wolfrum U, Roepman R. Usher syndrome: molecular links of pathogenesis, proteins and pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R262–270. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan L, Zhang M. Structures of usher syndrome 1 proteins and their complexes. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27:25–42. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00037.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiners J, Nagel-Wolfrum K, Jurgens K, Marker T, Wolfrum U. Molecular basis of human Usher syndrome: deciphering the meshes of the Usher protein network provides insights into the pathomechanisms of the Usher disease. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:97–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DS. Usher syndrome: animal models, retinal function of Usher proteins, and prospects for gene therapy. Vision Res. 2008;48:433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Wang L, Song H, Sokolov M. Current understanding of usher syndrome type II. Front Biosci. 2012;17:1165–1183. doi: 10.2741/3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J. Usher Syndrome: Genes, Proteins, Models, Molecular Mechanisms, and Therapies. In: Naz S, editor. Hearing Loss. Intech Open Access; Croatia: 2012. pp. 293–328. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keats BJB, Lentz J. Usher Syndrome Type II. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, editors. GeneReviews. University of Washington; Seattle: 1993–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keats BJB, Lentz J. Usher Syndrome Type I. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, editors. GeneReviews. University of Washington; Seattle: 1993–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puffenberger EG, Jinks RN, Sougnez C, Cibulskis K, Willert RA, Achilly NP, Cassidy RP, Fiorentini CJ, Heiken KF, Lawrence JJ, Mahoney MH, Miller CJ, Nair DT, Politi KA, Worcester KN, Setton RA, Dipiazza R, Sherman EA, Eastman JT, Francklyn C, Robey-Bond S, Rider NL, Gabriel S, Morton DH, Strauss KA. Genetic mapping and exome sequencing identify variants associated with five novel diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebermann I, Phillips JB, Liebau MC, Koenekoop RK, Schermer B, Lopez I, Schafer E, Roux AF, Dafinger C, Bernd A, Zrenner E, Claustres M, Blanco B, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Ruland R, Westerfield M, Benzing T, Bolz HJ. PDZD7 is a modifier of retinal disease and a contributor to digenic Usher syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1812–1823. doi: 10.1172/JCI39715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khateb S, Zelinger L, Mizrahi-Meissonnier L, Ayuso C, Koenekoop RK, Laxer U, Gross M, Banin E, Sharon D. A homozygous nonsense CEP250 mutation combined with a heterozygous nonsense C2orf71 mutation is associated with atypical Usher syndrome. J Med Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weil D, Blanchard S, Kaplan J, Guilford P, Gibson F, Walsh J, Mburu P, Varela A, Levilliers J, Weston MD, et al. Defective myosin VIIA gene responsible for Usher syndrome type 1B. Nature. 1995;374:60–61. doi: 10.1038/374060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verpy E, Leibovici M, Zwaenepoel I, Liu XZ, Gal A, Salem N, Mansour A, Blanchard S, Kobayashi I, Keats BJ, Slim R, Petit C. A defect in harmonin, a PDZ domain-containing protein expressed in the inner ear sensory hair cells, underlies Usher syndrome type 1C. Nat Genet. 2000;26:51–55. doi: 10.1038/79171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bitner-Glindzicz M, Lindley KJ, Rutland P, Blaydon D, Smith VV, Milla PJ, Hussain K, Furth-Lavi J, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, Barnes PD, O’Brien RE, Farndon PA, Sowden J, Liu XZ, Scanlan MJ, Malcolm S, Dunne MJ, Aynsley-Green A, Glaser B. A recessive contiguous gene deletion causing infantile hyperinsulinism, enteropathy and deafness identifies the Usher type 1C gene. Nat Genet. 2000;26:56–60. doi: 10.1038/79178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolz H, von Brederlow B, Ramirez A, Bryda EC, Kutsche K, Nothwang HG, Seeliger M, del CSCM, Vila MC, Molina OP, Gal A, Kubisch C. Mutation of CDH23, encoding a new member of the cadherin gene family, causes Usher syndrome type 1D. Nat Genet. 2001;27:108–112. doi: 10.1038/83667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bork JM, Peters LM, Riazuddin S, Bernstein SL, Ahmed ZM, Ness SL, Polomeno R, Ramesh A, Schloss M, Srisailpathy CR, Wayne S, Bellman S, Desmukh D, Ahmed Z, Khan SN, Kaloustian VM, Li XC, Lalwani A, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Nance WE, Liu XZ, Wistow G, Smith RJ, Griffith AJ, Wilcox ER, Friedman TB, Morell RJ. Usher syndrome 1D and nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness DFNB12 are caused by allelic mutations of the novel cadherin-like gene CDH23. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:26–37. doi: 10.1086/316954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Bernstein SL, Ahmed Z, Khan S, Griffith AJ, Morell RJ, Friedman TB, Wilcox ER. Mutations of the protocadherin gene PCDH15 cause Usher syndrome type 1F. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:25–34. doi: 10.1086/321277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alagramam KN, Yuan H, Kuehn MH, Murcia CL, Wayne S, Srisailpathy CR, Lowry RB, Knaus R, Van Laer L, Bernier FP, Schwartz S, Lee C, Morton CC, Mullins RF, Ramesh A, Van Camp G, Hageman GS, Woychik RP, Smith RJ. Mutations in the novel protocadherin PCDH15 cause Usher syndrome type 1F. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1709–1718. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weil D, El-Amraoui A, Masmoudi S, Mustapha M, Kikkawa Y, Laine S, Delmaghani S, Adato A, Nadifi S, Zina ZB, Hamel C, Gal A, Ayadi H, Yonekawa H, Petit C. Usher syndrome type I G (USH1G) is caused by mutations in the gene encoding SANS, a protein that associates with the USH1C protein, harmonin. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:463–471. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riazuddin S, Belyantseva IA, Giese AP, Lee K, Indzhykulian AA, Nandamuri SP, Yousaf R, Sinha GP, Lee S, Terrell D, Hegde RS, Ali RA, Anwar S, Andrade-Elizondo PB, Sirmaci A, Parise LV, Basit S, Wali A, Ayub M, Ansar M, Ahmad W, Khan SN, Akram J, Tekin M, Cook T, Buschbeck EK, Frolenkov GI, Leal SM, Friedman TB, Ahmed ZM. Alterations of the CIB2 calcium- and integrin-binding protein cause Usher syndrome type 1J and nonsyndromic deafness DFNB48. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1265–1271. doi: 10.1038/ng.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eudy JD, Weston MD, Yao S, Hoover DM, Rehm HL, Ma-Edmonds M, Yan D, Ahmad I, Cheng JJ, Ayuso C, Cremers C, Davenport S, Moller C, Talmadge CB, Beisel KW, Tamayo M, Morton CC, Swaroop A, Kimberling WJ, Sumegi J. Mutation of a gene encoding a protein with extracellular matrix motifs in Usher syndrome type IIa. Science. 1998;280:1753–1757. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weston MD, Luijendijk MW, Humphrey KD, Moller C, Kimberling WJ. Mutations in the VLGR1 gene implicate G-protein signaling in the pathogenesis of Usher syndrome type II. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:357–366. doi: 10.1086/381685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebermann I, Scholl HP, Charbel Issa P, Becirovic E, Lamprecht J, Jurklies B, Millan JM, Aller E, Mitter D, Bolz H. A novel gene for Usher syndrome type 2: mutations in the long isoform of whirlin are associated with retinitis pigmentosa and sensorineural hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2007;121:203–211. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adato A, Vreugde S, Joensuu T, Avidan N, Hamalainen R, Belenkiy O, Olender T, Bonne-Tamir B, Ben-Asher E, Espinos C, Millan JM, Lehesjoki AE, Flannery JG, Avraham KB, Pietrokovski S, Sankila EM, Beckmann JS, Lancet D. USH3A transcripts encode clarin-1, a four-transmembrane-domain protein with a possible role in sensory synapses. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:339–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fields RR, Zhou G, Huang D, Davis JR, Moller C, Jacobson SG, Kimberling WJ, Sumegi J. Usher syndrome type III: revised genomic structure of the USH3 gene and identification of novel mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:607–617. doi: 10.1086/342098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]