Abstract

Objectives

Despite a growing body of literature, uncertainty regarding the influence of physician dress on patients’ perceptions exists. Therefore, we performed a systematic review to examine the influence of physician attire on patient perceptions including trust, satisfaction and confidence.

Setting, participants, interventions and outcomes

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Biosis Previews and Conference Papers Index. Studies that: (1) involved participants ≥18 years of age; (2) evaluated physician attire; and (3) reported patient perceptions related to attire were included. Two authors determined study eligibility. Studies were categorised by country of origin, clinical discipline (eg, internal medicine, surgery), context (inpatient vs outpatient) and occurrence of a clinical encounter when soliciting opinions regarding attire. Studies were assessed using the Downs and Black Scale risk of bias scale. Owing to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, meta-analyses were not attempted.

Results

Of 1040 citations, 30 studies involving 11 533 patients met eligibility criteria. Included studies featured patients from 14 countries. General medicine, procedural (eg, general surgery and obstetrics), clinic, emergency departments and hospital settings were represented. Preferences or positive influence of physician attire on patient perceptions were reported in 21 of the 30 studies (70%). Formal attire and white coats with other attire not specified was preferred in 18 of 30 studies (60%). Preference for formal attire and white coats was more prevalent among older patients and studies conducted in Europe and Asia. Four of seven studies involving procedural specialties reported either no preference for attire or a preference for scrubs; four of five studies in intensive care and emergency settings also found no attire preference. Only 3 of 12 studies that surveyed patients after a clinical encounter concluded that attire influenced patient perceptions.

Conclusions

Although patients often prefer formal physician attire, perceptions of attire are influenced by age, locale, setting and context of care. Policy-based interventions that target such factors appear necessary.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comprehensive review of the topic strengthened by robust methodology, expansive literature search, stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, and use of an externally validated quality-tool to rate studies.

Filtering studies by the conceptual understanding that culture, tradition, patient expectations and settings influence perceptions allow for unique insight regarding whether and how physician attire influences perceptions.

Unique findings including the fact that attire preferences vary by geographic location, patient age and context of care.

The inclusion of a diverse number of study designs and patient populations introduces potential for unmeasured confounding or bias.

Although we created uniform measures to apply across all studies, diverse outcomes reporting related but ill-defined patient perceptions or preferences may limit inferential insights.

Introduction

The foundation of a positive patient–physician relationship rests on mutual trust, confidence and respect. Patients are not only more compliant when they perceive their doctors as being competent, supportive and respectful, but also more likely to discuss important information such as medication compliance, end-of-life wishes or sexual histories.1 2 Several studies have demonstrated that such relationships positively impact patient outcomes, especially in chronic, sensitive, and stigmatising problems such as diabetes mellitus, cancer or mental health disorders.3 4

In the increasingly rushed patient–physician encounter, the ability to gain a patient's confidence with the goal to optimise health outcomes has become a veritable challenge. Therefore, strategies that help in gaining patient trust and confidence are highly desirable. A number of studies have suggested that physician attire may be an important early determinant of patient confidence, trust and satisfaction.5–7 This insight is not novel; rather, interest in the influence of attire on the physician–patient experience dates back to Hippocrates.8 However, targeting physician attire to improve the patient experience has recently become a topic of considerable interest driven in part by efforts to improve patient satisfaction and experience.9 10

For physician attire to positively influence patients, an understanding of when, why and how attire may influence such perceptions is necessary. While several studies have examined the influence of physician attire on patients, few have considered whether or how physician specialty, context of care and geographic locale and patient factors such as age, education or gender may influence findings. This knowledge gap is important because such elements are likely to impact patient perceptions of physicians. Furthermore, the existing literature stands conflicted on the importance of physician attire. For instance, in a seminal review, Bianchi6 suggest “patients are more flexible about what they consider ‘professional dress’ than the professionals who are setting standards.” However, a more recent review reported that patients prefer formal attire and a white coat, noting that “these partialities had a limited overall impact on patient satisfaction and confidence in practitioners.”11 This dissonance remains unexplained and represents a second important knowledge gap in this area of research.

Therefore, to shed light on these issues, we conducted a systematic review of the literature hypothesising that patients will prefer formal attire in most settings. Additionally, we postulated that context of care will influence patient perceptions on attire, such that patients receiving care in acute-based or procedure-based settings are less likely to be influenced by attire.

Methods

Information sources and search strategy

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) when performing this systematic review.12 With the assistance of a medical reference librarian (AH), we performed serial searches for English and non-English studies that reported patient perceptions related to physician attire. MEDLINE via Ovid (1950–present), Embase (1946–present), and Biosis Previews via ISI Web of Knowledge (1926–present) and Conference Proceedings Index (dates) were systematically searched using controlled vocabularies for key words including a range of synonyms for clothing, physician and patient satisfaction (see online supplementary appendix). All human studies published in full-text, abstract or poster form were eligible for inclusion. No publication date, language or status restrictions were placed on the search. Additional studies of interest were identified manually searches of bibliographies. Serial searches were conducted between 2 July 2013 and May 2014; the search was last updated 15 May 2014.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Two authors (CMP and MM) independently determined study eligibility; any differences in opinion regarding eligibility were resolved by a third author (VC). Studies were included if they: (1) involved adults ≥18 years of age; (2) evaluated physician attire; (3) reported patient-centered outcomes such as satisfaction, perception, trust, attitudes or comfort; and, (4) studied the impact of attire on these outcomes. We excluded studies involving only paediatric and psychiatric patients because perceptions of attire were felt unreliable in these settings.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted from all included studies independently and in duplicate on a template adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration.13 For all studies, we abstracted the number of patients, context of clinical care, physician specialty, type of attire tested, method of assessing the impact of attire and outcomes including patient trust, satisfaction, confidence or synonyms thereof. When studies included paediatric and adult patients, we included the study but abstracted data only on adult patients when possible. Study authors were contacted to obtain missing or additional data via electronic mail. Owing to clinical and methodological heterogeneity in the design, conduct and outcomes reported within the included studies, formal meta-analyses were not attempted. Descriptive statistics were used to report data. Inter-rater agreement for study abstraction was calculated using Cohen’s κ statistic.

Definitions and classification

Physician attire was defined as either personal or hospital-issued clothing, with or without the donning of a white physician coat (recorded separately whenever possible). We considered formal attire as a collared shirt, tie and slacks for male physicians and blouse (with or without a blazer), skirt or suit pants for female physicians. Attire that did not meet these criteria was defined as casual (eg, polo shirts and blue jeans). Donning of hospital-issued or physician-owned ‘scrubs’ was recorded when these data were available.

To understand whether culture-influenced perceptions of physician attire, we assessed study outcomes by country and region of origin. Studies were also further categorised as follows: context of care was defined as the location where the patient was receiving care (eg, intensive care, urgent care, hospital or clinic). A clinical encounter was defined as a face-to-face clinical interaction between physician and patient during which the physician was wearing the study specific attire or the attire of interest. Acute care was defined as care provided in an emergency department, intensive care unit or urgent care unit; all other settings were classified non-acute. We defined family medicine, internal medicine, private practice clinics and inpatient medicine wards as studies involving medicine populations whereas studies that included patients from various specialties (eg, internal medicine and surgery) or various locations (eg, clinic, hospital were classified as being ‘mixed.’ Reports that included dermatology, orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology, podiatry and surgical populations were classified as ‘procedural’ studies.

To standardise and compare outcomes across studies, the following terms were used to indicate positive perceptions or preference for a particular attire: satisfaction, professionalism, competence, comfort, trust, confidence, empathy, authoritative, scientific, knowledgeable, approachable, ‘easy to talk to’, friendly, courteous, honest, caring, respect, kind, ‘spent enough time’, humorous, sympathetic, polite, clean, tidy, responsible, concerned, ‘ability to answer questions’ and ‘took problem seriously.’ Conversely, terms such as scruffy, aloof, unkempt, untidy, unpleasant, relaxed, intimidating, impolite, rushed were considered negative outcomes denoting non-preference for the tested attire.

Risk of bias in individual studies

As recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration, two authors independently assessed risk of study bias using the Downs and Black Scale.14 This instrument uses a point-based system to estimate the quality of a given study by rating domains such as internal and external validity, bias and statistical power. A priori, studies that received a score of 12 or greater were considered high quality. Inter-rater agreement for adjudication of study quality was calculated using Cohen’s κ statistic.

Results

Of 1040 citations, 45 studies met initial inclusion criteria. Following exclusion of duplicate and ineligible articles, 30 studies were included in the systematic review (figure 1).1 5 15–42 Included studies ranged in size from 77 to 1506 patients. Although many studies did not provide gender information, when identified, a similar number of male and female participants were included across studies (33% male vs 67% female in 25 studies).1 5 15 16 19–21 23–28 30–36 38–42 Three studies performed in obstetric and gynaecology populations included only female patients.20 23 36 Inter-rater agreement for agreement on eligibility and abstraction of data were excellent (κ=0.94 and 0.90, respectively).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Many of the included studies were conducted in the USA (n=10);1 17 19 20 22–24 31 36 37 however, other geographic locations including Canada (n=2),16 35 UK, Ireland and Scotland (n=5),18 25 26 34 39 Asia (n=4),5 21 28 41 other European nations (n=5),29 30 33 38 40 Australia and New Zealand (n=2),27 32 the Middle East (n=1)15 and Brazil (n=1)42 were also represented. With respect to temporality, 22 of the 30 included studies were published within the last decade1 5 15 16 19–23 25 26 29–33 36 38–42; however, several studies were published more than 10 years ago.17 18 24 27 28 34 35 37 Seven studies specified the inclusion of patients who had at least a high school or college-level education1 15 16 20 35 38 40; however, the remaining studies did not report the educational level of their population.

With respect to the specialties where studies were performed, a number of medical disciplines including internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, family practice, dermatology, podiatry and orthopaedics were represented. The context of care within the 30 individual studies varied substantially and spanned hospitalised and outpatient settings. Medical and surgical clinics, emergency departments, hospital wards, private family practice clinics, urgent and intensive care units, and military-based clinics were also featured in the included studies (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors, year, location | Study design | Clinical setting (context) | Patient characteristics |

Attire compared |

Clinical encounter (Y/N) | Perceptions/preferences measured | Influence/preference expressed for attire | Pertinent results and comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean age (years) | Education level | % Male | Types of attire | White coat specified | |||||||

| Al-Ghobain et al, 2012, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia15 | Picture-based survey and face-to-face interview of patients awaiting care | General medicine clinic (outpatient) | 399 | 37.2 | 66% were at least high-school educated | 57.9 | Males: formal attire, scrubs, national attire Females: formal attire, Scrubs |

Yes | No | Confidence Knowledge respect |

Yes; formal attire | ▸ Male and female patients preferred formal attire ▸ 85% indicated preference for white coats ▸ Confidence, competence, apparent medical knowledge and expertise was not significantly associated with the attire or gender of provider (p=0.238) |

| Au et al, 2013, Alberta, Canada16 | Cross-sectional, picture-based survey; family members reviewed pictures and rated factors such as age, sex, grooming, tattoos, etc | Three intensive care units (acute care) | 337 | N/R | 60% College or university educated | 32 | Formal attire+white coat, suit, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Caring competence Honesty knowledge |

Yes; formal attire and white coat | ▸ Formal attire+white coat was rated as being most important when first meeting a physician ▸ Neat grooming and visible name tags were also important ▸ When selecting preferred providers from a panel of pictures, formal attire and white coat were most preferred ▸ Physicians in formal attire: viewed as being most knowledgeable ▸ Physicians in scrubs or a white coat: viewed as being most competent to perform a procedure |

| Baevsky et al, 1998, Massachusetts, USA17 | Prospective encounter-based, non-randomised exit-survey of patients conducted after receiving care. Physicians alternated attire on daily basis | Urban urgent care clinic (acute care) | 596 | N/R | N/R | N/R | Formal attire+white coat, scrubs+white coat | Yes | Yes | Degree of concern knowledge Polite/courteous Satisfaction |

No preference | ▸ No differences seen between attires with regard to patient satisfaction ▸ Mean ranks were higher for scrubs+white coat regarding courtesy, seriousness and knowledge ▸ 18% of physicians broke from attire protocol during the study |

| Boon et al, 1994, Sheffield, England18 | Prospective questionnaire following clinical interaction | Accident and emergency department (acute care) | 329 | N/R | N/R | N/R | White coat, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | Yes | Professionalism Neat scruffy |

No preference | ▸ Style of dress did not affect patient perceptions of medical staff ▸ Average visual analogue scale results did not differ between white coat, causal attire and scrubs (9.14 vs 8.98 vs 8.98) ▸ However, patients often failed to correctly recall physician attire when surveyed |

| Budny et al, 2006, Iowa and NY USA19 | Description-based survey of patients awaiting care | Podiatric clinics in private practice and hospital-based settings (procedural) | 155 | 18–25: 7% 26–40: 15% 41–55: 32% 56–70: 19% >70: 26% |

N/R | 36 | Formal attire, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Confidence | Yes; formal attire | ▸ 68% of all patients reported more confidence if physicians donned formal attire ▸ Formal attire was preferred among older patients (Medicare) and patients who received care in private practice settings ▸ Females preferred formal attire more than male patients |

| Cha et al, 2004, Ohio, USA20 | Picture-based survey regarding patient preferences for attire | Obstetrics and gynaecology clinic at an academic medical centre (procedural) | 184 | Approximately 66% ≤25 years of age | Approximately 66% at least high-school educated | 0 | Formal attire+white coat, formal attire−white coat; scrubs+white coat; casual attire+white coat, casual attire−white coat, scrubs−white coat | Yes | No | Comfort Confidence |

Yes; scrubs+white coat | ▸ 63% of patients stated that physician clothing did not influence their comfort with the physician ▸ 62% reported that physician clothing did not affect their confidence in the physician ▸ However, following pictures, comfort level of patients and perceived competence of physicians were greatest for images of physicians dressed in white coats and scrubs. ▸ Comfort level was least for physicians wearing casual attire |

| Chang et al, 2011, Seoul, Republic of Korea21 | Picture-based survey regarding preferences for attire prior to clinical consultation | Alternative medicine clinic at an academic medical centre (outpatient) | 153 | 43.3 | N/R | 32 | White coat, formal attire, traditional attire casual attire |

Yes | No | Comfort Competence trust |

Yes; white coat | ▸ Patients most preferred white coats regardless of whether Western or oriental physician portrayed in photographs ▸ Competence and trustworthiness ranking: white coat, traditional, formal attire and, lastly casual attire ▸ Comfort ranking: traditional attire, white coat, formal attire and casual attire |

| Chung et al, 2012, Kyunggido, Republic of Korea5 | Prospective, non-randomised, clinical encounter-based survey of patients conducted after receiving care | Traditional Korean medical clinic (outpatient) | 143 | 37.7 | N/R | 34 | White coat, formal attire, traditional attire, casual attire | Yes | Yes | Comfort Competence Empathy Satisfaction trust |

Yes; white coat | ▸ White coat was associated with competence, trustworthiness and patient satisfaction ▸ Traditional attire led to greater patient comfort and contentment with the physician ▸ No specifics regarding clothing under white coat provided |

| Edwards et al, 2012, Texas, USA22 | Prospective non-randomised, clinical encounter-based questionnaire. Physician attire rotated after 12-weeks | Outpatient surgical clinic at a military teaching hospital (procedural) | 570 | N/R | N/R | N/R | scrubs+white coat, traditional attire | Yes | Yes | Appropriateness | No preference | ▸ Surgeon clothing did not affect patient's opinions ▸ Patients felt it was appropriate for surgeons to wear Scrubs in the clinic ▸ No preference regarding attire by 71% of those who replied ▸ 50% of patients in either group (scrubs vs no-scrubs) felt that white coats should be worn ▸ 30.7% response rate; demographic data not collected |

| Fischer et al, 2007, New Jersey, USA23 | Prospective non-randomised, clinical encounter-based questionnaire; physicians were randomly assigned to wear one of three attire types each week | Outpatient obstetrics and gynaecology clinics at a university hospital (procedural) | 1116 | 37.3 | N/R | 0 | Formal attire+white coat, casual attire±white coat, scrubs | Yes | Yes | Comfort competence Friendly and courteous Hurried Knowledge listened to concerns Professionalism Satisfaction |

No preference | ▸ Patient satisfaction with their physicians was high; attire did not influence satisfaction ▸ Physicians in all three groups were viewed as professional, competent and knowledgeable ▸ Among 20 physician providers, 8 preferred casual attire, 7 preferred formal attire, and 5 preferred scrubs |

| Friis and Tilles, 1988, California, USA24 | Picture-based survey; patients who had received care from a resident physician during a prior visit were surveyed regarding their preferences for physician attire | Internal medicine clinic, emergency room, internal medicine ward, community-based internal medicine clinic (mixed) | 200 | N/R (Mode: 20–29) | N/R | 40 | White coat Formal attire Casual attire |

Yes | Yes | Confidence Hurried Neatness Satisfaction sympathy |

No preference | ▸ Most patients voiced no attire preference; however, 64% said neatness of dress was moderately to very important ▸ 78% rated their physician as neat or very neat ▸ Variances between clinical settings: ward patients more frequently said female physicians should wear a white coat and skirt (27% vs 5%, p<.01) ▸ While participating physicians were all residents, level of resident training was not taken into account by the survey |

| Gallagher et al, 2008, Dublin, Ireland25 | Picture-based survey of patients awaiting care | outpatient endocrinology clinic in a tertiary referral hospital (outpatient) | 124 | 52.3 | N/R | 50 | White coat, formal attire, suit, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Appropriateness of attire Comfort |

Yes; White coat | ▸ White coat was most often preferred by both male and female patients ▸ Scrubs and casual attire were least preferred ▸ Limited description of casual attire worn by both genders of physicians and formal attire worn by female physicians were provided |

| Gherardi et al, 2009, West Yorkshire, England26 | Picture-based survey in multiple care settings | outpatient clinics, inpatient wards, emergency departments (mixed) | 511 | N/R | N/R | 44 | White coat, formal attire, suit, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Confidence | Yes; White coat | ▸ White coat was the most confidence-inspiring attire in all hospital settings ▸ Younger patients more tolerant of scrubs ▸ Patients had most confidence in physicians wearing Scrubs in the emergency department vs other settings ▸ White coat was worn with formal attire limiting ability to parse out impact of each element; survey conducted in a brief time frame |

| Gooden et al, 2001, Sydney, Australia27 | Cross-sectional, clinical encounter-based survey of hospitalised patients | Medical and surgical wards of two teaching hospitals (inpatient) | 154 | Median 54 | N/R | 58 | White coat, no white coat | Yes | Yes | Aloof Approachable Authoritativeness Competence Easy to talk to Friendly Knowledgeable Preference Professionalism Scientific |

Yes; White coat | ▸ Higher scores noted when white coat was worn ▸ 36% explicitly preferred physicians to wear White Coats ▸ Patient preference for physicians to wear a white coat correlated with preference to wear a uniform ▸ Older patients (53 or older) preferred white coats more than younger patients ▸ An imbalance between patients who saw providers with or without a white coat was reported (24% vs 76%) |

| Hartmans et al, 2014, Leuven, Belgium40 | Picture-based, cross-sectional survey administered online through social media as well as in-person in waiting rooms | University hospital-based outpatient clinic and related offsite clinics (outpatient) | 1506 | 38.4 | 70.1% completed at least high school | 32 | Formal attire+white coat, formal attire−white coat, semi-formal attire, casual attire | Yes | No | Confidence, ease with physician | Yes; Formal attire+white coat | ▸ Patients have the most confidence in a female doctor wearing formal attire+white coat, while they felt most at ease with a female physician in casual attire ▸ Most confidence inspiring outfit of the older male physician was formal attire+white coat, ▸ The response of ‘No preference’ was not included in this study |

| Ikusaka et al, 1999, Tokyo, Japan28 | Clinical encounter-based questionnaire; physician rotated wearing a white coat weekly | University hospital outpatient clinic (outpatient) | 599 | White coat group: 50 No white coat group: 47.8 |

N/R | 45 | Formal attire+white coat, formal attire−white coat | Yes | Yes | Ease with physician Satisfaction |

No preference | ▸ Although patients stated they preferred white coats, satisfaction was not statistically different between the groups ▸ Older patients ≥ 70 years of age preferred a white coat over those ≤70 (69% vs 52%, p=0.002) |

| Kersnik et al, 2005, Krajnska Gora, Slovenia29 | Patient allocation-blinded, clinical encounter-based survey; physicians alternated wearing a white coat daily | Outpatient, urban family practice (outpatient) | 259 | N/R | N/R | N/R | White coat, no white coat | Yes | Yes | Integrity Professionalism Satisfaction |

No preference | ▸ There were no significant difference in patient satisfaction between the two groups ▸ 34% and 19% of all respondents fully agreed or agreed that white coats symbolise professional integrity ▸ Conversely, 25.9% and 8.5% either fully disagreed or disagreed that the white coat represented professional integrity |

| Kocks et al, 2010, Groningen, Netherlands30 | Picture-based survey of patient preferences | Patients were interviewed at home; professionals were given a written survey at a symposium (mixed) | 116 | 78 | N/R | 56.9 | Formal attire, suit, business-casual attire, casual attire | No | No | Preference Trust |

Yes; Formal attire | ▸ Patients preferred formal attire and suit over other attires ▸ Professionals preferred formal attire and business-casual attire over casual attire ▸ In general, patients were more tolerant of casual attire and less likely to have style preference than professionals |

| Kurihara et al, 2014, Ibaraki, Niigata and Tokyo, Japan41 | Picture-based, self-administered questionnaires | outpatients at 5 pharmacies across Japan | 491 | 51.9 | N/R | 40.3 | Formal attire+white coat, formal attire−white coat, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Appropriateness | Yes; Formal attire+white coat | ▸ Formal attire+white coat was considered the most appropriate style of clothing followed by scrubs ▸ Formal attire without a white coat for female physicians was felt to be inappropriate in 73% of patients vs 24% who felt that formal attire without a white coat was inappropriate for male physicians. ▸ 73% of respondents felt that casual dress was inappropriate for male physicians vs 79.8% for female physicians ▸ There was a statistically significant increase in the number of subjects over 50 years of age who thought scrubs were in appropriate compared to those aged 20–34 years. ▸ Study survey response rate was 35% |

| Li and Haber, 2005, New York, USA31 | Patient-allocation blinded, picture-based, quasi-experimental before-and-after study; physicians alternated attire weekly | Urban emergency department in a university medical centre (acute care) | 111 | 42 | N/R | 53 | Formal attire+white coat, scrubs | Yes | Yes | Professionalism Satisfaction |

No preference | ▸ Physician attire was not associated with satisfaction or professionalism in the emergency department during the study ▸ No difference in attire preferences by patient age, gender, race, or physician gender and race were noted ▸ Hawthorne effect possible as physicians were aware of patient ratings and observations |

| Lill and Wilkinson, 2005, Christchurch, New Zealand32 | Picture-based survey of patient preferences | Inpatients and outpatients from a wide range of wards, medical and surgical clinics (mixed) | 451 | 55.9 | N/R | 47 | White coat, formal attire, semiformal semiformal with smile Casual |

Yes | Yes for inpatients (survey administered before clinical encounter in outpatients) | Preference for physician based on attire displayed in pictures | Yes; Semiformal attire with smile | ▸ Semi-formal attire with a smile was preferred by patients ▸ Older patients preferred male and female physicians with white coats more than other age groups ▸ Most patients thought physicians should always wear a badge ▸ Smiling option in pictures may have introduced bias as this was not used equally for all categories |

| Maruani et al, 2013, Tours, France33 | Picture-based, prospective cross- sectional study | Outpatient dermatology patients of a tertiary care hospital, 2 dermatological private consulting rooms (procedural) | 329 | 52.3 | N/R | 43.8 | White coat, formal attire, business-casual attire, casual attire | Yes | No | Confidence Importance of attire |

Yes; White coat | ▸ White coats were preferred by hospital and private practice outpatients significantly more than other attires, for both male and female physicians ▸ 60% of adult patients in either setting considered physician attire important |

| McKinstry and Wang, 1991, West Lothian and Edinburgh, Scotland34 | Picture-based, interviewer-led surveys of patients using eight standardised photographs of physicians in different attires | 5 outpatient general medicine clinics (outpatient) | 475 | N/R | N/R | 30.9 | Males: formal attire+white coat, formal attire−white coat, business-casual attire Females: formal attire+white coat; business-casual, casual attire |

Yes | No | Acceptability Confidence |

Yes; Formal attire+white coat | ▸ Male physicians: formal attire−white coat was preferred followed by formal attire+white coat ▸ Female physicians: casual attire scored significantly lower patients and higher socioeconomic levels preferred formal attire+white coat to a greater extent than others. ▸ Majority of patients felt that the way their doctor's dress is very important or quite important. ▸ Significant variations noted across sites suggest underlying patient- or site-level confounding |

| McLean et al, 2005, Surrey, England39 | Clinical encounter-based questionnaire with one of two providers dressed in military uniform or civilian formal attire | Fracture clinic in a ‘District Hospital’ (procedural) | 77 | 39 | N/R | 62 | Military uniform, formal attire | No | Yes | Approachable Confidence Humorous Hurried Intimidation Kindness Polite/courteous Professionalism |

Yes; Formal attire | ▸ Civilian formal attire was felt more professional by patients ▸ No statistical differences were noted with respect to other dimensions including kindness, approachability, or confidence across attires ▸ This is small study with a small number of patients and only two providers; generalisability appears limited |

| McNaughton-Filion et al, 1991, Ontario, Canada35 | Picture and description based-survey administered by a research-assistant or resident to both patients and physicians | Urban, university hospital family practice and community-based family practice clinic (Outpatient) | 80 | N/R | 54% College or university educated | 41 | Formal attire+white coat, formal attire−white coat, casual attire+white coat, casual attire−white coat, scrubs+white coat | Yes | No | Professionalism Trust and confidence |

Yes; Formal attire+white coat | ▸ Majority of patients surveyed believed formal attire+white coats in male physicians would be more likely to inspire trust & confidence. ▸ Preferred attire for female physicians was less clear ▸ Most physicians opined that they should dress professionally, but white coats were not necessary |

| Niederhauser et al, 2009, Virginia, USA36 | Picture and description-based survey of patient preferences | Hospital-based obstetrics and gynaecology clinics (procedural) | 328 | 26.4 | N/R | 0 | Military uniform+white coat military uniform−white coat, scrubs+white coat, scrubs−white coat | Yes | No | Comfort Confidence satisfaction |

Yes; Scrubs±white coat | ▸ 61% of patients preferred Scrubs ▸ 83% of patients did not express a preference for white coats. ▸ 12% reported attire affects confidence in their physician's abilities ▸ 13% reported attire affects how comfortable they are talking to their physician about general topics |

| Pronchik et al, 1998, Pennsylvania, USA37 | Clinical encounter-based, prospective survey; All male students, residents and attendings assigned to wear or not wear a necktie according to a specified schedule; female providers were excluded | Emergency department of a community teaching hospital (Acute care) |

316 | N/R | N/R | N/R | Necktie, no necktie | No | Yes | Satisfaction Competence |

No preference | ▸ Neckties did not influence patients’ impression of medical care, time spent, or overall provider competence ▸ Higher ‘general appearance’ ratings were noted among patients who believed their physician wore a necktie during their clinical encounter ▸ Of note, 28.6% of patients incorrectly identified their physician as having worn a necktie on a no necktie day |

| Rehman et al, 2005, South Carolina, USA1 | Picture-based, randomised, cross-sectional descriptive survey | Outpatient medicine clinic at a Veterans-Affairs Medical Center (outpatient) | 400 | 52.4 | 42.8% at least high school educated | 54 | Formal attire+white coat; formal attire−white coat, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Authoritative Compassionate Competence Confidence Preference responsible trustworthiness |

Yes; Formal attire+white coat | ▸ Significant preference for formal attire+white coat ▸ Female respondents placed more importance on female physician attire than that of male physician attire ▸ Trend toward less preference for formal attire+white coat when physician pictured was African–American |

| Sotgiu et al, 2012, Sassari, Italy38 | Picture and description-based questionnaire | Medical and surgical outpatient clinics (mixed) | 765 | 43.2 | 45.8% finished high school or college-level | 7.5 | Formal attire+white coat, casual attire+white coat, scrubs+white coat | Yes | No | ‘Willingness to share heath issues’ with each of the physicians, but data not reported | Yes; Scrubs+white coat | ▸ The greatest proportion of patients preferred scrubs+white Coat (47% for male physicians, 43.7% for female physicians respectively) followed by formal attire+white coat (30.7% for male physicians, 26.8% for female physicians) ▸ Male patients preferred Formal Attire+White Coat for both male and female physicians; female patients preferred scrubs+white coat for both male and female physicians. ▸ Younger patients chose scrubs+white coat more often than older patients; older patients preferred formal attire+white coat |

| Yonekura et al, 2013, Sao Paulo, Brazil42 | Picture-based survey of patient preferences | Inpatients and outpatients at a university hospital | 259 | 47.8 | N/R | 42.9 | White coat, formal attire+white coat, traditional attire, casual attire, scrubs | Yes | No | Cleanliness Competence ‘Concern for patients’ Confidence Knowledge |

Yes; White coat | ▸ The combined white coat options in the survey were the most preferred by patients across all measured perceptions ▸ White coat was preferred by patients in both routine outpatient appointments as well as emergency room visits ▸ Traditional attire was defined as ‘All White’ without a white coat for both male and female physician models ▸ Physicians surveyed in this study expressed a preference for formal attire+white coat for the male physician model and white coat for the female physician model |

Of the 30 included studies, 28 studied specific patient perceptions and preferences regarding physician attire,1 5 15–31 33–37 39–42 while 2 only measured preference attire.32 38 In total, more than 32 unique patient perceptions were reported across the included studies. The most common patient perceptions studied were confidence in their physician (n=12), satisfaction (n=9), professionalism (n=7), perceived competence (n=7), comfort (n=6) and knowledge (n=6). Studies obtained input from patients regarding how attire influenced their perceptions of physicians through a variety of measures, including written questionnaires, face-to-face question/answer sessions, and surveys either before or following clinical care episodes. The instruments used to obtain patient input regarding physician attire included pictures of male and female models dressed in various attire, written descriptions of attire, as well as feedback regarding physician encounters either before or after a clinical service was provided to the patient.

A preference for specific physician attire or positive influence of physician attire on patient perceptions was reported in 21 of the 30 studies (70%).1 5 15 16 19–21 25–27 30 32–36 38–42 When patients voiced a preference or were influenced by physician attire, formal attire was almost always preferred followed closely by white coats either with or without formal attire. In studies from the Far East, traditional attire was associated with increased patient comfort with their physician5 21; however, this was not the case in the single study from the Middle East where traditional apparel was not preferred by patients over formal attire.15 Notably, patient age was often predictive of attire preference with patients older than 40 years of age uniformly preferring formal attire compared to younger patients in seven studies.19 27 28 32 34 38 40 Conversely, younger patients often felt that scrubs were perfectly appropriate or preferred over formal attire.26 36 38 41 These preferences extended to items such as facial piercings, tattoos, loose hair, training shoes and informal foot wear in three studies among younger patients.19 32 41 Regardless of attire, being well-groomed in appearance and displaying visible nametags were viewed favorably by patients when this question was specifically asked in the included studies.

Influence of geography on attire preferences

Geography was found to influence perceptions of attire, perhaps reflecting cultural, fashion or ethnic expectations. For instance, only 4 of the 10 US-based studies reported that attire influenced patient perceptions regarding their physician. In comparison, Canadian studies reported a preference for formal attire and a white coat.16 35 Similarly, among five studies from the UK, Scotland and Ireland,18 25 26 34 39 four reported that patients preferred formal attire or white coats.25 26 34 39 Similarly, four of five studies from other European nations found that patient preferences, trust or satisfaction were influenced by physician attire.30 33 38 40 Of these four studies, three studies found a preference for formal attire or white coats30 33 40 compared to one where scrubs were preferred38 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stacked bar chart showing variation in patient preference for physician attire across geographic regions.

Six studies included patients from Asia, Australia and New Zealand.5 21 27 28 32 41 Of the four Asian studies,5 21 28 41 two were performed in Korea5 21 and two in Japan.28 41 Both studies from Korea concluded that physician attire and white coats positively influenced patient confidence, trust and satisfaction.5 21 While one Japanese study reported that the majority of patients older than 70 years preferred white coats, satisfaction was not statistically affected by white coats during consultations.28 Conversely, another study from Japan found that formal attire with a white coat was considered the most appropriate style of dress for a physician.41 However, the two studies conducted in Australia and New Zealand found that patients preferred white coats and formal attire when rating physicians.27 32 Similarly, the single study from the Middle-East found that 62% of patients preferred male physicians to wear formal attire whereas 73% preferred female physicians to wear a long skirt. As with the single study from Brazil, there was also a significant preference for a white coat to be worn, regardless of physician gender.15 42

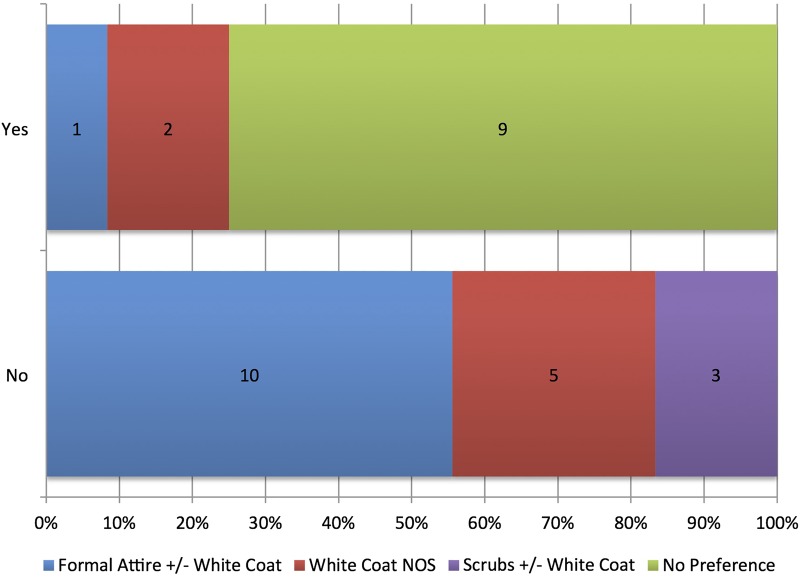

Influence of clinical encounters on attire preference

Of the 30 included studies, 12 studies surveyed patients regarding their opinions about physician attire following a clinical encounter.5 17 18 22–24 27–29 31 37 39 Within these 12 studies, only 3 (25%) reported that attire influenced patient perceptions of their physician.5 27 39 Formal attire without white coat was preferred in one of the three studies39; a white coat with other attire not specified was preferred in two studies.5 27 However, in the remaining nine studies, patients did not voice any attire preference following a clinical encounter suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the context of receiving care.

Conversely, clear preferences regarding physician attire were reported in 16 of 18 studies where patients received either written descriptions (n=1)19 or pictures of physician attire without a corresponding clinical interaction with a physician (n=17).1 15 16 20 21 25 26 30 32–36 38 40–42 The majority of these studies (n=10) preferred formal attire either with or without a white coat1 15 16 19 30 32 34 35 40 41; three studies reported a preference for scrubs with or without white coats,20 36 38 whereas a white coat with other attire not specified was preferred in five studies (figure 3).21 25 26 33 42

Figure 3.

Stacked bar chart showing variation in patient preference for physician attire with clinical encounters.

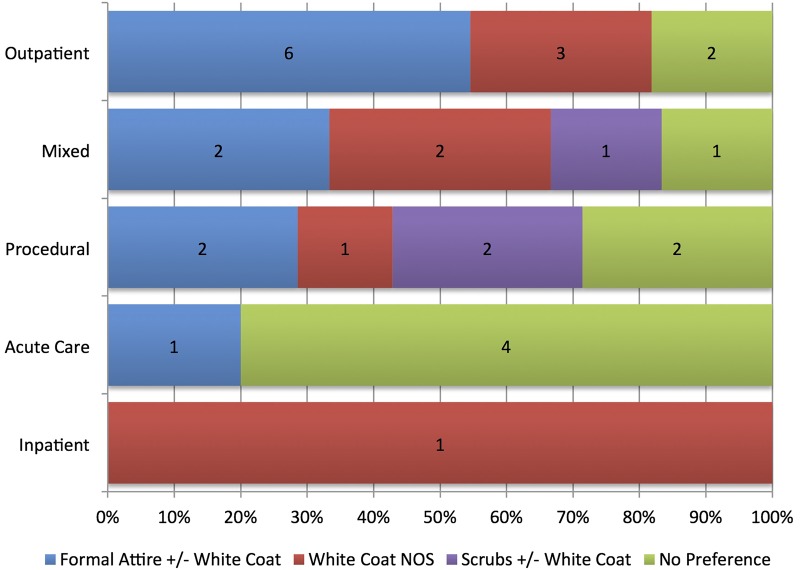

Influence of context of care on patient preferences for attire

Context of care also influenced attire preference. For example, six studies conducted in general medicine outpatient clinics reported that patients preferred formal attire with or without a white coat,1 15 34 35 40 41 while three reported preference for a white coat with other attire not specified.5 21 25 Only two studies reported no attire preferences in this specific medical discipline in this setting.28 29 Conversely, four of five studies conducted in acute care settings reported no attire preferences17 18 31 37; only one study reported a preference of formal attire with or without a white coats.16 Of the seven procedural studies that included patients from obstetrics and gynecology, gastroenterology, emergency care and surgery,19 20 22 23 33 36 39 three reported either no specific preference for attire22 23 39 or preference for scrubs over other attire.20 36 Only two of the seven studies reported preference for formal attire or white coats in these settings.19 33 Studies categorised as being ‘mixed’ in context (n=6) correspondingly reported heterogeneous preferences, spanning no preference for attire, to preference for formal attire, white coat and scrubs with white coats only24 26 30 32 38 42 (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Stacked bar chart showing variation in patient preference for physician attire across contextual aspects of care.

Risk of bias within included studies

We assessed risk of bias within the included 30 studies using the Downs and Black Quality Scale. Studies with higher quality were characterised by the fact that they more commonly reported characteristics of included and excluded patients and provided more accurate descriptions of attire based interventions. Using this scale, 8 of the 30 included studies were associated with higher methodological quality (table 2). Inter-rater agreement for study quality adjudication was excellent (κ=0.87).

Table 2.

Risk of bias within included studies

| Author, year, location | Clinical interaction? | Group | Does the study provide estimates of the random variability in the data for the main outcomes? | Have the characteristics of the patients included and excluded been described? | Were study subjects in different intervention groups recruited over the same period of time? | Were incomplete questionnaires excluded? | Reviewer scores | Risk of bias adjudication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer et al, 2007, New Jersey, USA23 | Yes | Surgery/procedural | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 of 27 | Low |

| Hartmans et al, 2014, Leuven, Belgium40 | No | Outpatient | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 14 of 27 | Low |

| Gooden et al, 2001, Sydney, Australia27 | No | Mixed | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 13 of 27 | Low |

| Baevsky et al, 1998, Massachusetts, USA17 | Yes | Acute care | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 of 27 | Low |

| Gherardi et al 2009, West Yorkshire, England26 | No | Mixed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 of 27 | Low |

| Lill and Wilkinson, 2005, Christchurch, New Zealand32 | No | Mixed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 of 27 | Low |

| Niederhauser et al, 2009, Virginia, USA36 | No | Surgery/procedural | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 of 27 | Low |

| Rehman et al, 2005, South Carolina, USA1 | No | Medicine | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 of 27 | Low |

| Pronchik et al, 1998, Pennsylvania, USA37 | Yes | Acute care | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11.5 of 27 | Moderate |

| Au et al, 2013, Alberta, Canada16 | No | Acute care | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11.5 of 27 | Moderate |

| Li and Haber 2005, New York, USA31 | Yes | Acute care | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11.5 of 27 | Moderate |

| Al-Ghobain et al, 2012, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia15 | No | Medicine | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 of 27 | Moderate |

| Boon et al, 1994, Sheffield, England18 | Yes | Acute care | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 of 27 | Moderate |

| Chung et al, 2012, Kyunggido, Republic of Korea5 | Yes | Medicine | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 of 27 | Moderate |

| Edwards et al, 2012, Texas, USA22 | Yes | Surgery/procedural | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 of 27 | Moderate |

| Kersnik et al, 2005, Krajnska Gora, Slovenia29 | Yes | Medicine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 of 27 | Moderate |

| Yonekura et al, 2013, Sao Paulo, Brazil42 | No | Mixed | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 of 27 | Moderate |

| Maruani et al, 2013, Tours, France33 | No | Surgery/procedural | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10.5 of 27 | Moderate |

| Cha et al, 2004, Ohio, USA20 | No | Surgery/procedural | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10.5 of 27 | Moderate |

| Chang et al, 2011, Seoul, Republic of Korea21 | No | Medicine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.5 of 27 | Moderate |

| Budny et al, 2006, Iowa and NY, USA19 | No | Surgery/procedural | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 of 27 | Moderate |

| Ikusaka et al, 1999, Tokyo, Japan28 | Yes | Medicine | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 of 27 | Moderate |

| McLean et al, 2005, Surrey, England39 | Yes | Surgery/procedural | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 of 27 | Moderate |

| Kurihara et al, 2014, Ibaraki, Niigata and Tokyo, Japan41 | No | Outpatient | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 of 27 | Moderate |

| Friis and Tilles, 1988, California, USA24 | Yes | Mixed | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9.5 of 27 | High |

| Sotgiu et al, 2012, Sassari, Italy38 | No | Mixed | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9.5 of 27 | High |

| Gallagher et al, 2008, Dublin, Ireland25 | No | Medicine | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 of 27 | High |

| Kocks et al, 2010, Groningen, Netherlands30 | No | Medicine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 of 27 | High |

| McNaughton-Filion et al, 1991, Ontario, Canada35 | No | Medicine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.5 of 27 | High |

| McKinstry and Wang, 1991, West Lothian and Edinburgh, Scotland34 | No | Medicine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 of 27 | High |

A priori, studies that received a score of 12 or greater were considered to be at low risk of bias; scores of 10–12 moderate risk of bias; and scores less than 10 at high risk of bias.

Scores for key questions that differentiated studies at high versus moderate and low risk of bias are shown.

Scores shown represent independently rated and agreed-on ratings by two reviewers.

Discussion

In this systematic review examining the influence of physician attire on a number of patient perceptions, we found that formal attire with or without white coats, or white coat with other attire not specified was preferred in 60% of the 30 included studies.1 5 15 16 19 21 25–27 30 32–35 39–42 However, no specific preference for physician attire was demonstrated in nine studies and preference for scrubs was noted in three procedural studies. Importantly, we found that elements such as patient age and context of care in addition to geography and population appear to influence perceptions regarding attire. For example, patients who received clinical care were less likely to voice preference for any type attire than patients that did not, perhaps exemplifying the importance of interaction over appearance. Similarly, older patients and those in European or Asian nations were more likely to prefer formal attire than those from the USA Collectively, these findings shed new light on this topic and suggest that although professional attire may be an important modifiable aspect of the physician–patient relationship, finding a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to optimal physician dress code is improbable. Rather, ‘tailored’ approaches to physician attire that take into account patient, provider and contextual factors appear necessary.

In an ever-changing medical landscape, patient satisfaction has become a focal point for providers and health-systems. Therefore, preferences regarding physician attire have become a topic of considerable interest as a means to improve first-impressions and perceptions regarding quality of care. Why may patient perceptions and preferences vary so greatly across studies? Multiple reasons are possible. First, our review supports the notion that patients often harbour conscious and unconscious biases when it comes to their preferences regarding physician attire.7 37 For example, while many patients did not report an attire preference when directly surveyed, several of our included studies found that images of patients dressed in white coats or formal suits were more often associated with perceptions of trust and confidence even if patients also expressed no specific preferences regarding attire.16 17 37 In support, studies that included physician encounters were less likely to find specific preferences (3/12 studies) compared to studies conducted outside of a physician–patient meeting (18/18 studies). These likely subconscious beliefs are important to acknowledge, first, especially patients from a ‘baby-boomer’ generation who often conflate formal attire with physician competence and confidence.19 34 Second, the influence of cultural aspects on attire expectations is likely to be substantial on attire preferences. As noted in our review, studies originating from the UK, Asia, Ireland and Europe most often expected formal attire with or without white coats; attire that did not include these dress-codes were least preferred. Third, the influence of context of care on expectations regarding physician dress is important to acknowledge. A defined ‘uniform’ for physicians may be an expectation for certain patients and/or specific settings. Finally, it is important to remember that sartorial style is but skin-deep and not a surrogate for medical knowledge or competence. Even the best-dressed physicians are likely to fare poorly in the eyes of their patients if medical expertise is perceived absent.

Our results must be interpreted in the context of important limitations. First, like all systematic reviews, this is an observational study that can only assess trends, not causality, using available data. Second, the inclusion of a diverse number of study designs and patient populations creates a high-likelihood of unmeasured confounding and bias. Third, only eight of the included studies were rated as being at low risk-of-bias using the Downs and Black scale. This finding reflects in general the limited quality of this literature and suggests that while physician attire may be important, more methodologically rigorous studies are needed to better understand and truly harness this aspect to improve patient satisfaction. Fourth, a wide variety of related but often ill-defined patient perceptions or preferences were measured within the included studies; although we collapsed these categories into more uniform measures, our ability to draw insights from these diverse outcomes is limited. Finally, we specifically did not take into consideration risk of infection associated with attire. Since a recent study examined this in considerable detail,11 our review complements the literature in this regard.

Despite these limitations, our review has notable strengths including a thorough literature search, stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, and use of an externally validated quality-tool to rate studies. Second, our review was guided by the conceptual understanding that culture, tradition, patient expectations and settings influence perceptions related to physician attire. Filtering and assessing studies in this fashion provided us with insights when, if and how physician attire influences patient perceptions. Finally, we also included 16 new articles that have been published since the last comprehensive review of this topic6; inclusion of these new studies (including a substantial number of studies from diverse countries and healthcare settings) lends greater external validity and importance to our findings.

How may hospitals and healthcare facilities use these data to effect policy decisions? Our review suggests that formal attire is almost always preferred with respect to physician attire may be unwise given the heterogeneous evidence-base and methodological quality of available data. After contacting human resource professionals, other administrators and researching information available on their public websites at all 10 of the top 10 2013–2014 US News & World Report Best Hospitals, we found that 5 had written guidelines calling for formal and professional attire throughout their institutions. Our findings suggest that such sweeping policies that apply to all healthcare specialties, settings and acuities of care may paradoxically not improve patient satisfaction, trust or confidence. Rather, interventions that test the impact of when and how care is delivered, types of patients encountered, and approaches used to measure patient preferences are needed. In order to better tailor physician attire to patient preferences and improve available evidence, we would recommend that healthcare systems capture the ‘voice of the customer’ in individual care locations (eg, intensive care units and emergency departments) during clinical care episodes. The use of a standardised tool that incorporates variables such as patient age, educational level, ethnicity and background will help contextualise these data in order to derive individualised policies not only for each area of the hospital, but also for similar health systems in the world.

In summary, the influence of physician attire on patient perceptions is complex and multifactorial. It is likely that patients harbour a number of beliefs regarding physician dress that are context and setting-specific. Studies targeting the influence of such elements represent the next logical step in improving patient satisfaction. Hospitals and healthcare facilities must begin the hard work of examining these preferences using standardised approaches in order to improve patient satisfaction, trust and clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Drs Edwards, Gallagher, Stelfox, Fischer, Kocks, Gherardi, Chae, Dore, Maruani, Wilkinson, Baddini-Martinez, and Budny who provided additional unpublished data for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: VC, CMP, SS and MM were involved in the concept and design. VC, CMP, SS, MM, AH and JJP were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. VC, CMP, SS, MM, AH and JJP were involved in the drafting and critical revision. VC, CMP, SS, MM, AH and JJP were involved in the final approval.

Funding: VC is supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS022835-01).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors have posted their data sets on Dryad.

References

- 1.Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW et al. . What to wear today? Effect of doctor's attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med 2005;118:1279–86. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V et al. . Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:269–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K et al. . A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adher 2012;6:39–48.. 10.2147/PPA.S24752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:144–54. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10431.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung H, Lee H, Chang DS et al. . Doctor's attire influences perceived empathy in the patient-doctor relationship. Patient Education and Counseling, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi MT. Desiderata or dogma: what the evidence reveals about physician attire. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:641–3. 10.1007/s11606-008-0546-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt LJ. On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1277–81. 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hippocrates Jones WHS, Potter P et al. . Hippocrates. London; New York: Heinemann; Putnam, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus R, Culver DH, Bell DM et al. . Risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection among emergency department workers. Am J Med 1993;94:363–70. 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90146-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kremer W. Would you trust a doctor in a T-shirt? BBC News Magazine, 2013.

- 11.Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S et al. . Healthcare personnel attire in non-operating-room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35:107–21. 10.1086/675066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green G. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed 10 Feb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Ghobain MO, Al-Drees TM, Alarifi MS et al. . Patients’ preferences for physicians’ attire in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2012;33:763–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Au S, Khandwala F, Stelfox HT. Physician attire in the intensive care unit and patient family perceptions of physician professional characteristics. JAMA internal medicine 2013;173:465–7. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baevsky RH, Fisher AL, Smithline HA et al. . The influence of physician attire on patient satisfaction. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:82–4. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boon D, Wardrope J. What should doctors wear in the accident and emergency department? Patients perception. J Accid Emerg Med 1994;11:175–8. 10.1136/emj.11.3.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ et al. . The physician's attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2006;96:132–8. 10.7547/0960132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cha A, Hecht BR, Nelson K et al. . Resident physician attire: does it make a difference to our patients? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1484–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang D-S, Lee H, Lee H et al. . What to wear when practicing oriental medicine: patients’ preferences for doctors’ attire. J Altern Complement Med 2011;17:763–7. 10.1089/acm.2010.0612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards RD, Saladyga AT, Schriver JP et al. . Patient attitudes to surgeons’ attire in an outpatient clinic setting: substance over style. Am J Surg 2012;204:663–5. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer RL, Hansen CE, Hunter RL et al. . Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:186.e1–86.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friis R, Tilles J. Patients’ preferences for resident physician dress style. Fam Pract Res J 1988;8:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallagher J, Waldron Lynch F, Stack J et al. . Dress and address: patient preferences regarding doctor's style of dress and patient interaction. Ir Med J 2008;101:211–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A et al. . Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patients’ preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med 2009;9:519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gooden BR, Smith MJ, Tattersall SJN et al. . Hospitalised patients’ views on doctors and white coats. Med J Aust 2001;175: 219–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikusaka M, Kamegai M, Sunaga T et al. . Patients’ attitude toward consultations by a physician without a white coat in Japan. Intern Med 1999;38:533–6. 10.2169/internalmedicine.38.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kersnik J, Tusek-Bunc K, Glas KL et al. . Does wearing a white coat or civilian dress in the consultation have an impact on patient satisfaction? Eur J Gen Pract 2005;11:35–6. 10.3109/13814780509178018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kocks JWH, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Berkelmans PGJI. [Clothing make the doctor—patients have more confidence in a smartly dressed GP]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2010;154:A2898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li SF, Haber M. Patient attitudes toward emergency physician attire. J Emerg Med 2005;29:1–3. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. Br Med J 2005;331:1524–7. 10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruani A, Leger J, Giraudeau B et al. . Effect of physician dress style on patient confidence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:e333–7. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKinstry B, Wang JX. Putting on the style: what patients think of the way their doctor dresses. Br J Gen Pract 1991;41:270, 75–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNaughton-Filion L, Chen JS, Norton PG. The physician's appearance. Fam Med 1991;23:208–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niederhauser A, Turner MD, Chauhan SP et al. . Physician attire in the military setting: does it make a difference to our patients? Mil Med 2009;174:817–20. 10.7205/MILMED-D-00-8409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pronchik DJ, Sexton JD, Melanson SW et al. . Does wearing a necktie influence patient perceptions of emergency department care? J Emerg Med 1998;16:541–3. 10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00036-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sotgiu G, Nieddu P, Mameli L et al. . Evidence for preferences of Italian patients for physician attire. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:361–7 10.2147/PPA.S29587%5B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLean C, Patel P, Sullivan C et al. . Patients’ perception of military doctors in fracture clinics—does the wearing of uniform make a difference? J R Naval Med Serv 2005;91:45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartmans C HS, Lagrain M, Asch KV et al. . The Doctor's New Clothes: Professional or Fashionable? Primary Health Care 2014;3:145 10.4172/2167-1079.1000145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pacific family medicine 2014;13:2 10.1186/1447-056X-13-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yonekura CL, Certain L, Karen SK et al. . Perceptions of patients, physicians, and Medical students on physicians’ appearance. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira 2013;59:452–9. 10.1016/j.ramb.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.