Abstract

Transient receptor potential ankyrin type 1 (TRPA1) and vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptors are coexpressed in vagal pulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves. Because both these receptors are sensitive to a number of endogenous inflammatory mediators, it is conceivable that they can be activated simultaneously during airway inflammation. This study aimed to determine whether there is an interaction between these two polymodal transducers upon simultaneous activation, and how it modulates the activity of vagal pulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves. In anesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats, the reflex-mediated apneic response to intravenous injection of a combined dose of allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, a TRPA1 activator) and capsaicin (Cap, a TRPV1 activator) was ∼202% greater than the mathematical sum of the responses to AITC and Cap when they were administered individually. Similar results were also observed in anesthetized mice. In addition, the synergistic effect was clearly demonstrated when the afferent activity of single vagal pulmonary C-fiber afferents were recorded in anesthetized, artificially ventilated rats; C-fiber responses to AITC, Cap and AITC + Cap (in combination) were 0.6 ± 0.1, 0.8 ± 0.1, and 4.8 ± 0.6 impulses/s (n = 24), respectively. This synergism was absent when either AITC or Cap was replaced by other chemical activators of pulmonary C-fiber afferents. The pronounced potentiating effect was further demonstrated in isolated vagal pulmonary sensory neurons using the Ca2+ imaging technique. In summary, this study showed a distinct positive interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1 when they were activated simultaneously in pulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves.

Keywords: inflammation, TRPA1, TRPV1, AITC, capsaicin

both transient receptor potential ankyrin type 1 (TRPA1) and vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptors are tetrameric membrane proteins with four identical subunits forming a ligand-gated nonselective cation channel (29, 42). In addition to having a similar protein structure as members of the superfamily of TRP channels, both channels are known to play important roles in the inflammation-induced hyperalgesia in various somatic and visceral organs (4, 5, 37, 39). In situ hybridization and immunofluorescence studies have shown that TRPA1 and TRPV1 are colocalized in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) nociceptive neurons (37). Furthermore, electrophysiological studies have demonstrated that these two channels may interact with each other in the same neurons; for example, TRPA1 is desensitized by capsaicin, a selective TRPV1 agonist, via Ca2+-dependent pathway in sensory neurons (2). On the other hand, a potentiating effect of TRPA1 activation on the TRPV1 sensitivity has also been reported in DRG neurons and heterologously transfected cells (35).

In the respiratory tract, TRPA1 is localized in a subset of TRPV1-expressing vagal sensory neurons (27), similar to their distribution pattern in DRG neurons. Both channels are abundantly expressed in the vagal bronchopulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves (27) that are known to play an important role in the regulation of airway functions in normal and pathophysiological conditions (8, 22). Since both TRPA1 and TRPV1 can be activated and sensitized by a number of inflammatory mediators endogenously released in the airways, such as proton, reactive oxygen species, prostanoids, and bradykinin (4, 6, 23, 32, 39, 44), it is conceivable that they can be activated simultaneously during airway inflammatory reaction. Hence, this study was carried out to investigate whether there is an interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1 upon simultaneous activation, and how this interaction may modulate the activity of vagal pulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This study comprised two parts: in vivo and in vitro studies. The experimental procedures described below were in accordance with the recommendation in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health and also approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In Vivo Study

Animal preparation.

The experiments were carried out in two rodent species: Sprague-Dawley rats (352.9 ± 8.3 g, n = 55) and C57BL6/J mice (27.3 ± 1.8 g, n = 6). Animals were initially anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of α-chloralose (rat: 100 mg/kg; mouse: 70 mg/kg) and urethane (rat: 500 mg/kg; mouse: 1,000 mg/kg) dissolved in a 2% borax solution; supplemental doses (one-tenth of the initial dose) of the same anesthetics were injected intravenously to maintain abolition of pain reflexes induced by tail-pinch. For administration of pharmacological agent(s), a catheter was inserted into the left jugular vein and advanced until its tip was positioned just above the right atrium. A catheter was inserted into femoral artery and connected to a pressure transducer (Statham P23AC, Hato Rey, Puerto Rico) for recording the arterial blood pressure (ABP) and heart rate (HR). A short tracheal cannula was inserted just below the larynx via a tracheotomy. Body temperature was maintained at ∼36°C by means of heating pad placed under the animal lying in a supine position. At the end of experiment, animals were euthanized by intravenous injection of 3M KCl (2 ml for rats and 0.2 ml for mice).

Study 1: pulmonary chemoreflex response.

Animals breathed spontaneously through the tracheal cannula. Respiratory flow was measured by a heated pneumotachograph (University of Kentucky Center for Manufacturing) connected to a differential pressure transducer (MP45-14; Validyne, Northridge, CA), and integrated by an integrator to give tidal volume (VT). Pulmonary chemoreflex responses were measured in each animal when intravenous injections of allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, a selective TRPA1 agonist, 0.8–1.2 mg/kg in rats and 0.3–0.6 mg/kg in mice) and capsaicin (Cap, a selective TRPV1 agonist, 0.75 μg/kg in rats and 0.25–0.50 μg/kg in mice) were administered individually first, and then in combination in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats (n = 6) and mice (n = 6); 20 min was allowed to elapse between two consecutive injections to avoid tachyphylaxis.

Respiratory frequency (f), VT, and expiratory duration (TE) were analyzed on a breath-by-breath basis using a data-acquisition system (TS-100; Biocybernetics, Taipei, Taiwan). To determine the intensity of apneic response, the apneic ratio was calculated by dividing the longest TE occurring within the first 5 breaths after the injection by the baseline TE that was averaged over 20 breaths immediately preceding the injection.

Study 2: pulmonary C-fiber activity.

Single-unit activities of vagal pulmonary C-fibers were recorded from anesthetized, open-chest, and artificially ventilated rats. VT and f were set at 8 ml/kg and 50 breaths/min (7025; UGO Basile, Comerio-Varese, Italy), respectively, to mimic those of anesthetized, unilaterally vagotomized rats. The right cervical vagus nerve was sectioned, and its caudal end was placed on a small dissecting platform and immersed in a pool of mineral oil. A thin filament was teased away from the desheathed nerve trunk and placed on a platinum-iridium hook electrode. Action potentials were amplified by a preamplifier (P511K; Grass Technologies, Warwick, RI), and monitored by an audio monitor (AM8RS; Grass Technologies). The thin filament was further split until the afferent activity arising from a single unit was electrically isolated. The afferent activity of a single unit was first searched by hyperinflation (3–4 times VT) and then identified by the immediate (delay < 1 s) response to an intravenous bolus injection of a larger dose of Cap (1 μg/kg). At the end of the experiment, the general locations of pulmonary C-fiber endings were identified by their responses to the gentle pressing of the lungs with a blunt-ended glass rod. A total of 65 C-fibers were studied in 49 rats.

Pulmonary C-fiber activities were recorded when intravenous injections of AITC (0.50–0.75 mg/kg) and Cap (0.35–0.75 μg/kg) were administered individually first, and then in combination; 20 min elapsed between two injections. In a separate study series, an identical protocol was followed when AITC was replaced by cinnamaldehyde (1.5–2.0 mg/kg), another selective activator of TRPA1. To investigate if the C-fiber responses were uniquely generated by the interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1 activations, we replaced either AITC or Cap by one of the three known chemical stimulants of C-fibers: phenylbiguanide (PBG, 2–4 μg/kg), a 5-HT3 receptor agonist (25); adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP, 0.6–2.0 mg/kg), an agonist of P2X2 and P2X3 receptors (19); and adenosine (Ado, 0.02–0.60 mg/kg), an A1 adenosine receptor agonist (16). To avoid the stimulation of pulmonary C-fibers generated by a larger volume of bolus injection, a combined dose of AITC and Cap was injected in the same volume as that for the single injections.

Fiber activity (FA) was continuously recorded and analyzed for 20 s before and 60 s after each injection. Baseline FA was averaged over the 10-s period immediately preceding the injection, and the peak response was defined as the maximum 5-s average FA within the first 10 s after the injection.

In Vitro Study

Fluorescent labeling and isolation of vagal pulmonary sensory neurons.

Sensory neurons innervating the lungs and airways were identified by retrograde labeling from the lungs by using the fluorescent tracer 1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (20). Young Sprague-Dawley rats (130–180 g) were anesthetized by inhalation of vaporized isoflurane (2% in O2). After a small midline incision was made on the ventral neck skin, DiI (0.2 mg/ml; 0.05 ml) was instilled into the trachea and lung via a needle (28 gauge). The incision was then closed by tissue adhesive (Vetbond; 3M, St. Paul, MN). Seven to ten days later, DiI-pretreated animals were anesthetized and decapitated. The head was immediately immersed in ice-cold DMEM/F-12 solution followed by quick extraction of nodose and jugular ganglia. Each ganglion was then desheathed, cut, and placed in a mixture of type IV collagenase (0.04%) and dispase II (0.02%), and incubated for 80 min in 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. After digestion, centrifugation and resuspension, cells were dissociated by gentle trituration with small-bore, fire-polished Pasteur pipettes. Myelin debris was discarded after centrifugation of the dispersed cell suspension (500 g, 8 min). The cell pellets were resuspended in the modified DMEM/F-12 solution (20), plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips, and then incubated overnight (5% CO2 in air at 37°C).

Study 3: measurement of Ca2+ transient in rat pulmonary sensory neurons.

Cultured cells (as described above) were washed and maintained in an extracellular solution (ECS). Ca2+ transients were measured in these cells with a digital fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 100; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a variable filter wheel (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and a digital CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) (15). Cells were incubated with 5 μM Fura-2 AM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), a Ca2+ indicator, for 30 min at 37°C, rinsed (×3) with ECS, and then allowed to deesterify for 30 min before use. Dual images (340- and 380-nm excitation, 510-nm emission) were collected, and pseudocolor ratiometric images were monitored during the experiments by using the software Axon Imaging Workbench (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA).

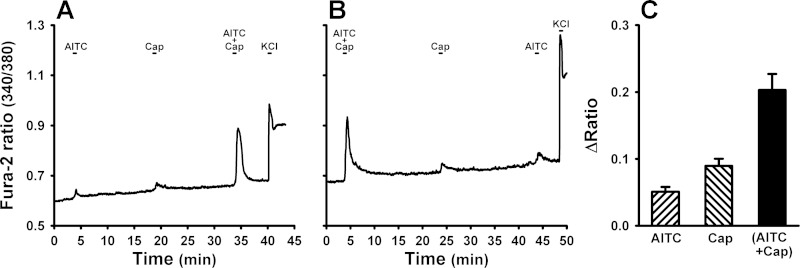

A total of 156 DiI-labeled neurons from six rats were studied. The coverslip containing the cells was mounted into a chamber continuously perfused with an ECS during the experiment by a gravity-fed valve-controlled system (VC-66CS, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) at a constant rate of ∼2 ml/min. The KCl solution (60 mM, 20 s) was perfused at the end of each experimental run to determine the cell viability. Ca2+ transients were recorded and compared when AITC (150 μM, 30 s) and Cap (100–150 nM, 30 s) were administered individually first, and then in combination; >15 min elapsed between two consecutive challenges. The order of administration was reversed in 109 neurons. The Fura-2 fluorescence 340/380 ratio was continuously analyzed at 2-s intervals, and the Ca2+ transient was measured as increase in the 340/380 ratio (ΔRatio): the difference between the peak amplitude (4-s average) after the challenge and the baseline (30-s average).

Statistical Analysis

In both in vivo and in vitro studies, data were compared using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. All data are reported as means ± SE.

Chemical Agents

In the in vivo study, stock solutions of Cap (250 μg/ml), AITC (50 mg/ml), and cinnamonaldehyde (50 mg/ml) were prepared in 10% Tween 80, 10% ethanol, and 80% saline, and that of ATP (20 mg/ml), Ado (10 mg/ml), and PBG (1 mg/ml) were prepared in saline. These stock solutions were stored at −20°C, and prepared daily at the desired concentrations for injection by dilution with isotonic saline based on the animal's body weight. In the in vitro study, desired concentrations of the chemical agents were prepared in a similar manner, except that the ECS, instead of saline, was used as the diluent. The ECS contained (in mM) 5.4 KCl, 136 NaCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and a pH level adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH and the osmolarity to 300 mOsm. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) except dispase II (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and Fura-2 AM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

RESULTS

Study 1

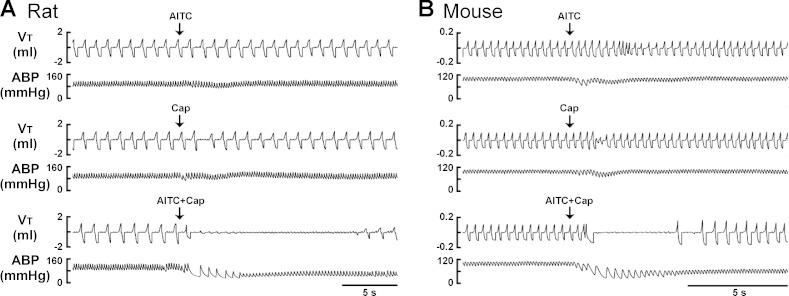

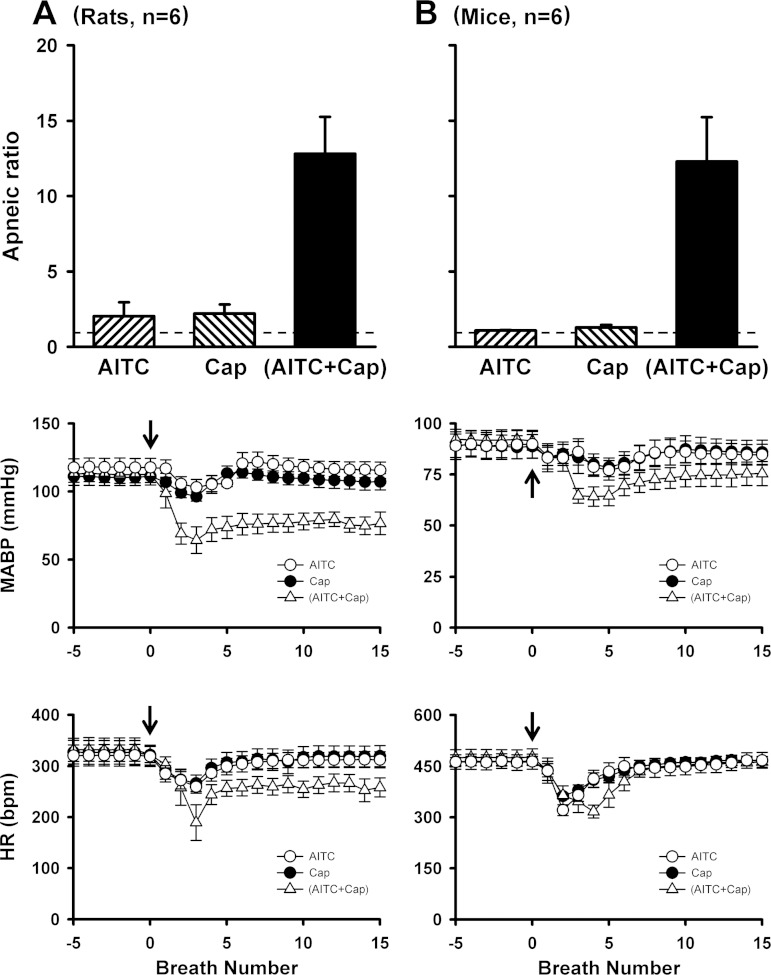

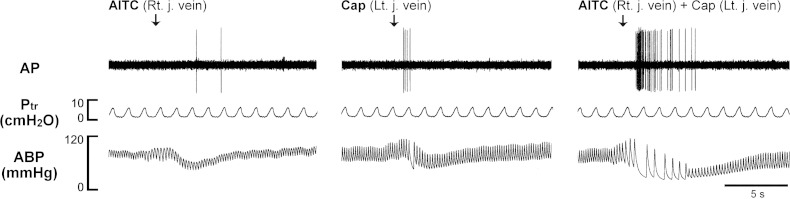

To avoid nonselective activation of TRPA1 and TRPV1 receptors (11, 13), only low (slightly above threshold) doses of AITC (0.8–1.2 mg/kg for rats and 0.3–0.6 mg/kg for mice) and Cap (0.75 μg/kg for rats and 0.25–0.50 μg/kg for mice) were used, respectively, in this study. Figure 1A shows representative tracings of acute respiratory and cardiovascular responses to intravenous injections of AITC, Cap, and a combination of AITC and Cap in an anesthetized, spontaneously breathing rat. Injection of AITC or Cap immediately (within 1–3 breaths) evoked a modest apneic response. In a sharp contrast, the apneic response to the injection of a combination of the same doses of AITC and Cap was markedly potentiated, accompanied by intense bradycardia and hypotension. The group data showed that the apneic ratios triggered by injections of AITC alone and Cap alone were 2.0 ± 0.9 and 2.2 ± 0.6, respectively, whereas a combined injection of AITC and Cap at the same doses elevated the apneic ratio to 12.8 ± 2.4 (P < 0.05, n = 6; Fig. 2A), which was 202% greater than the mathematical sum of TRPA1 and TRPV1 responses (Fig. 2A). This synergistic effect was also clearly demonstrated in mice (Fig. 1B); the apneic response to intravenous injection of AITC and Cap in combination was 425% greater than the mathematical sum of the responses to the same doses of AITC and Cap when they were injected individually (P < 0.05, n = 6; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Experimental records illustrating the synergistic effects of transient receptor potential ankyrin type 1 (TRPA1) and vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) agonists on pulmonary chemoreflex in spontaneously breathing rat (A) and mouse (B). Arrows depict intravenous bolus injections of allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, a TRPA1 agonist; 0.8 mg/kg for rat, 0.6 mg/kg for mouse; top panels), capsaicin (Cap, a TRPV1 agonist; 0.75 μg/kg for rat, 0.5 μg/kg for mouse; middle panels), and a combination of AITC and Cap with each at the same dose as that administered alone (bottom panels). The same volume of chemical solutions (0.15 ml in rat and 0.05 ml in mouse) was delivered in each injection regardless whether a single chemical or two chemicals in combination were given. The interval between injections was 20 min. VT, tidal volume; ABP, arterial blood pressure. Body weights of the rat and the mouse were 374 g and 28.1 g, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Synergistic effects of TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonists on pulmonary chemoreflex responses in rats and mice. AITC dose: 0.8–1.2 mg/kg for rats and 0.3–0.6 mg/kg for mice; Cap dose: 0.75 μg/kg for rats and 0.25–0.50 μg/kg for mice. “AITC + Cap,” responses to a combination of AITC and Cap with each at the same dose as that administered alone in the same animal. The volume injected (0.15 ml for rats and 0.05 ml for mice) was the same in all injections. Top panels: the apneic ratio was calculated as maximum expiratory duration (TE) occurring during the first 5 breaths after injection divided by average of 20 breaths of the baseline TE. Dashed line represents apneic ratio of 100% level (no apnea). Middle and bottom panels: responses of mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) and heart rate (HR) to injections of AITC alone, Cap alone, and a combination of AITC and Cap. Arrows depict the time of injections. Data are means ± SE (n = 6 for both rats and mice).

Study 2

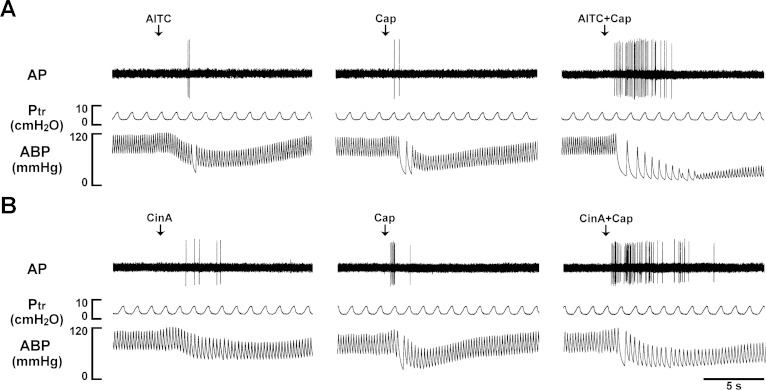

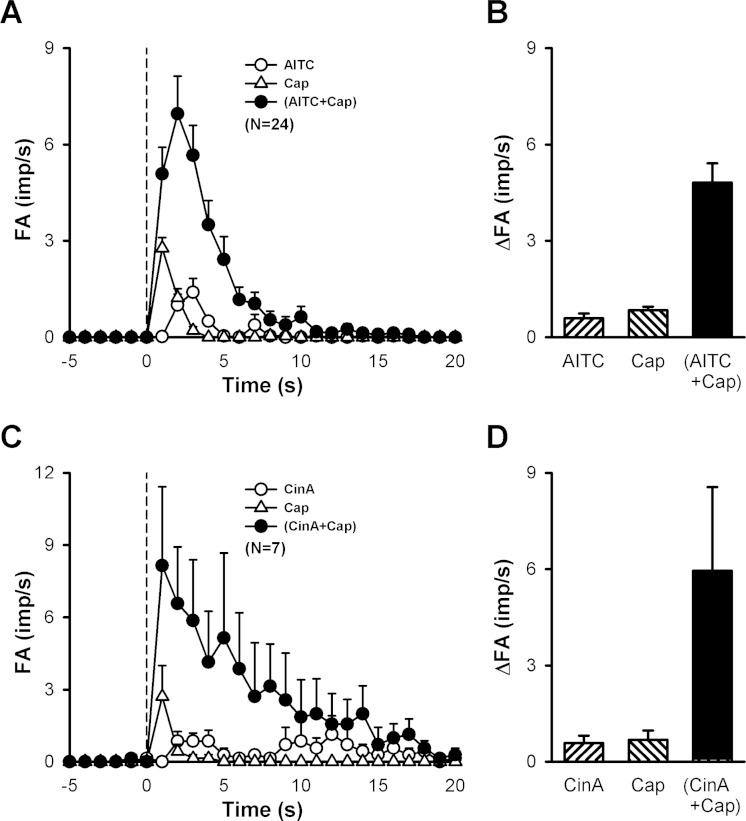

Intravenous injections of low doses of AITC (0.50–0.75 mg/kg) and Cap (0.35–0.75 μg/kg) immediately evoked pulmonary C-fiber discharge (e.g., Fig. 3A, left and middle panels); in comparison, the latency of the C-fiber response to AITC (2–3 s) was slightly, but consistently, longer than that of Cap (∼1 s). When the same doses of AITC and Cap were injected in combination, the afferent activity was strikingly amplified (Fig. 3A, right panel), accompanied by pronounced bradycardia and hypotension; no potentiation was found in only 5 of the 24 C-fibers studied. Group data showed that the peak fiber activity evoked by an injection of AITC and Cap in combination (4.8 ± 0.6 impulses/s; n = 24) was significantly greater than that evoked by AITC alone (0.6 ± 0.1 impulses/s; P < 0.05), Cap alone (0.8 ± 0.1 impulses/s; P < 0.05), or the mathematical sum of the two (1.4 ± 0.2 impulses/s; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Notably, the duration of fiber discharge was also markedly prolonged by the combined injection of AITC and Cap (Fig. 4A): 2.24 ± 0.28, 1.82 ± 0.15, and 5.65 ± 0.74 s after injections of AITC alone, Cap alone, and a combination of AITC and Cap, respectively (P < 0.05). This strong potentiation was also found when cinnamaldehyde, another selective agonist of TRPA1, was administered in combination with Cap (Fig. 3B), which clearly amplified both the peak activity and duration of the C-fiber discharge (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Experimental records illustrating the synergistic effects of TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonists on pulmonary C-fibers in anesthetized and artificially ventilated rats. A: responses of pulmonary C-fiber arising from the lower lobe of right lung to intravenously injections of AITC (0.75 mg/kg; left panel), Cap (0.75 μg/kg; middle panel), and a combination of AITC and Cap at the same doses (right panel). B: responses of pulmonary C-fiber arising from the lower lobe of right lung to intravenously bolus injections of cinnamaldehyde (CinA, 1.8 mg/kg; left panel), Cap (0.50 μg/kg; middle panel), and a combination of CinA and Cap at the same doses (right panel). The same volume (0.15 ml) was delivered in all injections, first into the catheter (dead space volume 0.2 ml) and then flushed (at arrow) into the circulation by a bolus of 0.3 ml saline. The interval between injections was 20 min. Rat body weights for A and B were 310 and 280 g, respectively. AP, action potential; Ptr, tracheal pressure; ABP, arterial blood pressure.

Fig. 4.

Synergistic effects of TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonists on pulmonary C-fiber afferent activity in anesthetized rats. A: histograms of pulmonary C-fibers activity (FA) to intravenous injections (dashed line) of AITC (0.50–0.75 mg/kg), Cap (0.35–0.75 μg/kg), and a combination of AITC and Cap (each at the same dose as that injected separately in the same fiber). B: data in A are converted to ΔFA, which is calculated as the difference between the peak FA (5-s average) and the 10-s average of the baseline FA in each fiber. Descriptions of C and D are similar to that of A and B, except that AITC was replaced by cinnamaldehyde (CinA, 1.5–2.0 mg/kg). Data are means ± SE. Imp/s, impulses per second.

To test the possibility that certain unknown chemical product(s) was formed after AITC and Cap were mixed in solution and contributed to the potentiating effect, we injected AITC and Cap simultaneously but separately into right and left jugular venous catheters, respectively. The pronounced amplification of the response was similar to that elicited by one bolus injection of the combined solution (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Experimental records illustrating the synergistic effects of AITC and Cap on a pulmonary C-fiber when they were injected via different venous catheters in an anesthetized and artificially ventilated rat. AITC (0.6 mg/kg, left panel) and Cap (0.5 μg/kg, middle panel) were injected via the catheters inserted in right and left jugular veins, respectively; the same doses of AITC and Cap were injected separately but simultaneously (right panel). The interval between injections was 20 min. Rt. j., right jugular; Lt. j., left jugular. Rat body weight: 342 g. For detailed explanations, see legend of Fig. 3.

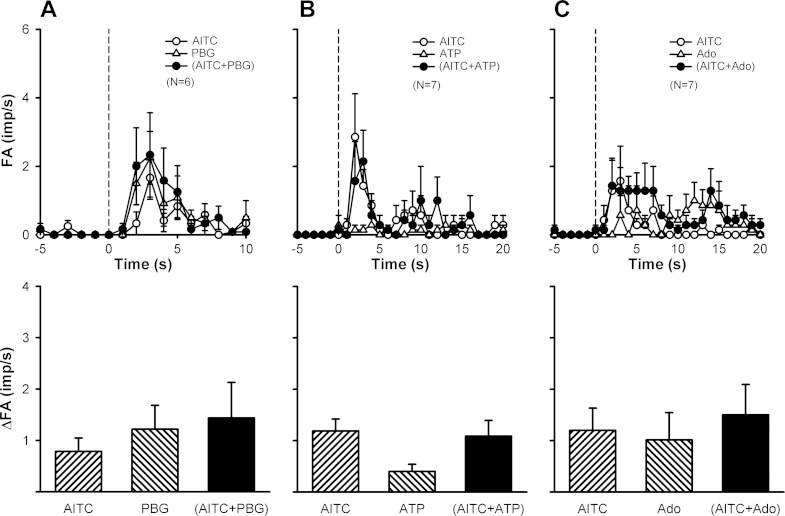

To determine if simultaneous activations of both TRPA1 and TRPV1 are required in generating this synergistic effect, we studied the C-fiber responses when either AITC (Fig. 6) or Cap (Fig. 7) was replaced by another known chemical activator of pulmonary C-fibers, such as PBG, ATP, and Ado. In distinct contrast, the average peak fiber activity evoked by the combined injection was not higher than the mathematical sum of two individual injections in any of these combinations (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6.

A lack of synergistic effect when the TRPA1 agonist was replaced by other known C-fiber activators. The TRPA1 agonist was replaced by phenylbiguanide (PBG; 2.0–4.0 μg/kg; A), ATP (0.75–1.0 mg/kg; B), or adenosine (Ado; 0.02–0.05 mg/kg; C). Dose of capsaicin (Cap) was 0.20–0.75 μg/kg. For detailed explanations, see the legend of Fig. 4.

Fig. 7.

A lack of synergistic effect when the TRPV1 agonist was replaced by other known C-fiber activators. The TRPV1 agonist was replaced by PBG (2.0–4.0 μg/kg; A), ATP (0.6–2.0 mg/kg; B) or Ado (0.15–0.60 mg/kg; C). Dose of AITC was 0.25–1.0 mg/kg. For detailed explanations, see the legend of Fig. 4.

Study 3

Application of a low concentration of AITC or Cap alone evoked a mild and transient increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (measured by the Fura-2 340/380 ratio) in isolated rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons, whereas the Ca2+ transients were markedly elevated by a combined challenge of AITC and Cap in the same neurons (e.g., Fig. 8A). This potentiation was also found when the order of administration was reversed (e.g., Fig. 8B). Group data indicated that the response, as measured by Δ(340/380 ratio), evoked by a combined challenge of AITC and Cap, was significantly greater than the mathematical sum of the responses to the same concentrations of AITC and Cap when they were administered individually (P < 0.05, n = 156; Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration evoked by TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonists in isolated rat pulmonary sensory neuron(s). A: experimental record illustrating responses to AITC (150 μM for 30 s), Cap (100 nM for 30 s), and a combination of AITC and Cap in a pulmonary jugular sensory neuron. KCl (60 mM for 20 s) was applied to test the cell vitality at the end of the experiment. B: experimental record illustrating responses to a reversed sequence of challenges in a different pulmonary jugular sensory neuron; the concentrations of AITC and Cap were the same as that in A. C: averaged group data (156 DiI-labeled cells). The intracellular Ca2+ concentration was measured as the Fura-2 fluorescence 340/380 ratio, and ΔRatio was calculated as the difference between peak ratio (averaged over 4-s interval) and baseline ratio (average over 30-s interval); “AITC + Cap” was the response to a combination of AITC and Cap with each at the same concentration as that was administered separately. Data are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

Both TRPA1 and TRPV1 are polymodal transducers abundantly expressed in vagal bronchopulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves (22, 27, 45). Both these TRP channels can be activated by a number of endogenous chemical mediators, for example, TRPV1 by hydrogen ion, anandamide and N-arachidonyl dopamine (14, 18), and TRPA1 by 4-hydroxynonenal, 4-oxononenal, bradykinin, and reactive oxygen species (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide, etc.) (3, 5, 7, 24, 38). Furthermore, the sensitivity of these receptors can be enhanced by certain endogenous inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandin E2 and bradykinin (14, 18, 20). It is, therefore, highly possible that both TRPA1 and TRPV1 can be activated simultaneously during airway inflammatory reaction.

This study demonstrated that a simultaneous activation of both TRPA1 and TRPV1 receptors generated a distinct synergistic effect on vagal pulmonary C-fiber sensory nerves, which was manifested by a pronounced potentiation of the pulmonary chemoreflex responses. A similar synergistic effect was also observed in isolated vagal pulmonary sensory neurons, indicating that the positive interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1 occurs primarily at the sensory neurons. It appears that this interaction occurs specifically between TRPA1 and TRPV1 because the synergy was completely absent when the selective agonist of one of these channels was replaced by other chemical activators of pulmonary C-fibers. This striking synergistic effect is not species-dependent because a similar effect was also observed in the pulmonary chemoreflex responses in mice (Fig. 1).

In this study, low doses of AITC and Cap were chosen for selectively activating TRPA1 and TRPV1, respectively, because recent studies reported that AITC at a higher concentration (3 mM) can activate TRPV1 in DRG and transfected cells (11, 13). Indeed, both AITC and Cap delivered alone at these low doses induced only very modest responses in pulmonary chemoreflexes, C-fiber discharges, and Ca2+ transients in this study. In a striking contrast, distinctly amplified responses were evoked when the same low doses of AITC and Cap were delivered in combination.

We questioned if the synergistic effect was generated by certain unknown chemical product(s) formed when AITC (or cinnamaldehyde) and Cap were mixed in solution before injection. This possibility can be ruled out because the potentiated responses persisted when these two chemical agents were injected simultaneously, but via two separate routes (Fig. 5).

Results of this study suggest that a functional linkage between TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels in these sensory neurons is probably an important contributing factor. However, the underlying mechanism(s) of this synergistic effect is not yet known, and the relative roles and contributions of TRPA1 and TRPV1 also remain to be determined. When AITC and Cap were administered in combination, did it enhance the current through TRPA1, TRPV1, both these channels, or some yet unidentified channel(s)? The elevated responses of these channels may involve either or both of the two possible mechanisms: increases in receptor expression and channel sensitivity. Schmidt et al. (34) indicated that application of mustard oil (AITC) to TRPA1-transfected cells triggered the TRPA1 trafficking to the plasma membrane. They also found that application of Cap raised cell surface TRPA1 protein expression, but not that of TRPV1 in the TRPA1/TRPV1-coexpressing cells. It has been reported that a translocation of TRPV1 from intracellular pool to plasma membrane led to TRPV1 sensitization (40, 43). However, in those studies described above, a much longer duration (5–30 min) of pretreatment with receptor agonists was required for the trafficking and translocation of these proteins to take place. In comparison, in our study the potentiating effect was immediately (within 1–2 s) evoked by a combined dose of TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonists. Thus we do not believe that the change in receptor expression and translocation is a plausible explanation for the synergistic effect observed in our study.

Another mechanism possibly involved in this potentiating effect that merits further consideration is an enhanced sensitivity of TRPA1 and/or TRPV1. Cumulative evidence suggests that the intracellular second messengers, such as Ca2+ or cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), may participate in the TRPA1-TRPV1 interaction. Intracellular Ca2+ can activate TRPA1 by binding the EF-hand domain in its NH2 terminus (10, 46). In addition, increased intracellular Ca2+ might also modulate the protein kinases (PKs), such as PKC and PKA, which further resulted in phosphorylation and sensitization of TRPV1 (17, 30, 41). Activation of TRPV1 can trigger more Ca2+ influx, which may in turn lead to TRPA1 activation (1, 4). On the other hand, a recent study showed that TRPA1 activation induced Ca2+ influx and elevated cAMP levels, which then activated PKA and led to TRPV1 sensitization (35).

Staruschenko and coworkers (36) and Salas and coworkers (33) recently reported that functional heteromeric channels can be formed from TRPA1 and TRPV1 on the cytoplasmic membrane, and that TRPV1 can influence intrinsic characteristics of the TRPA1 channel, probably through direct interaction of the channels within the complex, independent of the change of intracellular Ca2+. Whether and to what extent the TRPA1-TRPV1 interaction occurring in the heteromeric TRPA1-TRPV1 complexes contributes to the synergistic effect observed in our study requires further investigation.

It is well documented that TRPA1 and TRPV1 are also expressed in the nonneuronal cells (12), although the levels of protein expression, particularly for TRPV1, are considerably lower in other cell types. TRPA1 expression was found in airway epithelial cells, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, etc.; and the TRPV1 expression detected in bronchial epithelial cells (26). Thus it is conceivable that activation of TRPA1 may have triggered the release of intermediate mediator(s) from other target cells in the airways and pulmonary vessels, which in turn led to the sensitization of C-fiber afferents to Cap. Indeed, recent studies have shown that TRPA1 or TRPV1 activation on bronchial epithelial cells promoted proinflammatory mediator secretion (28, 31). However, the fact that onset of this synergistic effect arose so rapidly (1–2 s) after the injection seems to argue against such a possibility. Furthermore, this potentiating effect was also found in isolated pulmonary sensory neurons based upon our Ca2+ data, suggesting that the positive interaction occurs more likely at the sensory nerves.

The C-fiber sensory nerve endings expressing TRPA1 and TRPV1 are extensively found in the airway mucosa as well as in the deeper layer of airway tissue (45). Upon activation, they elicit centrally mediated reflex responses, which include bronchoconstriction and mucus hypersecretion via the cholinergic pathway, accompanied by the sensation of airway irritation and urge to cough (8, 22). Activation of these sensory nerves can also trigger release of tachykinins and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) from the sensory terminals, which can act on a number of effector cells in the respiratory tract (e.g., smooth muscles, cholinergic ganglia, mucous glands, immune cells), and elicit the local “axon reflexes” such as bronchoconstriction, protein extravasation, and inflammatory cell chemotaxis (9, 21). Because both TRPA1 and TRPV1 are sensitive to a number of endogenous inflammatory mediators (3, 5, 7, 14, 18, 24, 38), it is probable that they can be activated simultaneously during acute or chronic airway inflammatory reaction. The synergistic effect of activating these two channels will amplify the intensity of bronchopulmonary C-fiber discharge as demonstrated in this study, which may lead to the manifestation of various symptoms of airway hypersensitivity. Whether this effect occurs in patients with airway inflammatory diseases remains to be determined.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-67379 and HL-96914, and Department of Defense DMRDP/ARATD award administered by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) under Contract Number W81XWH-10-2-0189.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., M.K., and L.-Y.L. conception and design of research; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., T.R., and L.-Y.L. performed experiments; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., and L.-Y.L. analyzed data; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., T.R., M.K., and L.-Y.L. interpreted results of experiments; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., and L.-Y.L. prepared figures; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., M.K., and L.-Y.L. drafted manuscript; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., M.K., and L.-Y.L. edited and revised manuscript; Y.-J.L., R.-L.L., T.R., M.K., and L.-Y.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A preliminary report of this study has been presented as an abstract in the 2014 Experimental Biology Meeting (San Diego, CA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopian AN. Regulation of nociceptive transmission at the periphery via TRPA1-TRPV1 interactions. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 12: 89–94, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Jeske NA, Hargreaves KM. Transient receptor potential TRPA1 channel desensitization in sensory neurons is agonist dependent and regulated by TRPV1-directed internalization. J Physiol 583: 175–193, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andre E, Campi B, Materazzi S, Trevisani M, Amadesi S, Massi D, Creminon C, Vaksman N, Nassini R, Civelli M, Baraldi PG, Poole DP, Bunnett NW, Geppetti P, Patacchini R. Cigarette smoke-induced neurogenic inflammation is mediated by alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes and the TRPA1 receptor in rodents. J Clin Invest 118: 2574–2582, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bautista DM, Jordt SE, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell 124: 1269–1282, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bautista DM, Pellegrino M, Tsunozaki M. TRPA1: A gatekeeper for inflammation. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 181–200, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belvisi MG, Dubuis E, Birrell MA. Transient receptor potential A1 channels: insights into cough and airway inflammatory disease. Chest 140: 1040–1047, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessac BF, Jordt SE. Breathtaking TRP channels: TRPA1 and TRPV1 in airway chemosensation and reflex control. Physiology 23: 360–370, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleridge JCG, Coleridge HM. Afferent vagal C fibre innervation of the lungs and airways and its functional significance. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 99: 1–110, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Swert KO, Joos GF. Extending the understanding of sensory neuropeptides. Eur J Pharmacol 533: 171–181, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doerner JF, Gisselmann G, Hatt H, Wetzel CH. Transient receptor potential channel A1 is directly gated by calcium ions. J Biol Chem 282: 13180–13189, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everaerts W, Gees M, Alpizar YA, Farre R, Leten C, Apetrei A, Dewachter I, van Leuven F, Vennekens R, De Ridder D, Nilius B, Voets T, Talavera K. The capsaicin receptor TRPV1 is a crucial mediator of the noxious effects of mustard oil. Curr Biol 21: 316–321, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes ES, Fernandes MA, Keeble JE. The functions of TRPA1 and TRPV1: moving away from sensory nerves. Br J Pharmacol 166: 510–521, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gees M, Alpizar YA, Boonen B, Sanchez A, Everaerts W, Segal A, Xue F, Janssens A, Owsianik G, Nilius B, Voets T, Talavera K. Mechanisms of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation and sensitization by allyl isothiocyanate. Mol Pharmacol 84: 325–334, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geppetti P, Materazzi S, Nicoletti P. The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1: role in airway inflammation and disease. Eur J Pharmacol 533: 207–214, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu Q, Kwong K, Lee LY. Ca2+ transient evoked by chemical stimulation is enhanced by PGE2 in vagal sensory neurons: role of cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. J Neurophysiol 89: 1985–1993, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong JL, Ho CY, Kwong K, Lee LY. Activation of pulmonary C fibres by adenosine in anaesthetized rats: role of adenosine A1 receptors. J Physiol 508: 109–118, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeske NA, Diogenes A, Ruparel NB, Fehrenbacher JC, Henry M, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. A-kinase anchoring protein mediates TRPV1 thermal hyperalgesia through PKA phosphorylation of TRPV1. Pain 138: 604–616, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia Y, Lee LY. Role of TRPV receptors in respiratory diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1772: 915–927, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwong K, Kollarik M, Nassenstein C, Ru F, Undem BJ. P2X2 receptors differentiate placodal vs. neural crest C-fiber phenotypes innervating guinea pig lungs and esophagus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L858–L865, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwong K, Lee LY. PGE2 sensitizes cultured pulmonary vagal sensory neurons to chemical and electrical stimuli. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 1419–1428, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee LY, Gu Q. Role of TRPV1 in inflammation-induced airway hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9: 243–249, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee LY, Yu J. Sensory nerves in lung and airways. Compr Physiol 4: 287–324, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YJ, Hsu HH, Ruan T, Kou YR. Mediator mechanisms involved in TRPV1, TRPA1 and P2X receptor-mediated sensory transduction of pulmonary ROS by vagal lung C-fibers in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 189: 1–9, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YS, Hsu CC, Bien MY, Hsu HC, Weng HT, Kou YR. Activations of TRPA1 and P2X receptors are important in ROS-mediated stimulation of capsaicin-sensitive lung vagal afferents by cigarette smoke in rats. J Appl Physiol 108: 1293–1303, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mair ID, Lambert JJ, Yang J, Dempster J, Peters JA. Pharmacological characterization of a rat 5-hydroxytryptamine type3 receptor subunit [r5-HT3A(b)] expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Br J Pharmacol 124: 1667–1674, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGarvey LP, Butler CA, Stokesberry S, Polley L, McQuaid S, Abdullah H, Ashraf S, McGahon MK, Curtis TM, Arron J, Choy D, Warke TJ, Bradding P, Ennis M, Zholos A, Costello RW, Heaney LG. Increased expression of bronchial epithelial transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133: 704–712, e704, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nassenstein C, Kwong K, Taylor-Clark T, Kollarik M, Macglashan DM, Braun A, Undem BJ. Expression and function of the ion channel TRPA1 in vagal afferent nerves innervating mouse lungs. J Physiol 586: 1595–1604, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nassini R, Pedretti P, Moretto N, Fusi C, Carnini C, Facchinetti F, Viscomi AR, Pisano AR, Stokesberry S, Brunmark C, Svitacheva N, McGarvey L, Patacchini R, Damholt AB, Geppetti P, Materazzi S. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 channel localized to non-neuronal airway cells promotes non-neurogenic inflammation. PLos One 7: e42454, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T, Peters JA. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev 87: 165–217, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Numazaki M, Tominaga T, Toyooka H, Tominaga M. Direct phosphorylation of capsaicin receptor VR1 by protein kinase Cepsilon and identification of two target serine residues. J Biol Chem 277: 13375–13378, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reilly CA, Johansen ME, Lanza DL, Lee J, Lim JO, Yost GS. Calcium-dependent and independent mechanisms of capsaicin receptor (TRPV1)-mediated cytokine production and cell death in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 19: 266–275, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan T, Lin YJ, Hsu TH, Lu SH, Jow GM, Kou YR. Sensitization by pulmonary reactive oxygen species of rat vagal lung C-fibers: the roles of the TRPV1, TRPA1, and P2X receptors. PLos One 9: e91763, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salas MM, Hargreaves KM, Akopian AN. TRPA1-mediated responses in trigeminal sensory neurons: interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1. Eur J Neurosci 29: 1568–1578, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt M, Dubin AE, Petrus MJ, Earley TJ, Patapoutian A. Nociceptive signals induce trafficking of TRPA1 to the plasma membrane. Neuron 64: 498–509, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spahn V, Stein C, Zollner C. Modulation of transient receptor vanilloid 1 activity by transient receptor potential ankyrin 1. Mol Pharmacol 85: 335–344, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staruschenko A, Jeske NA, Akopian AN. Contribution of TRPV1-TRPA1 interaction to the single channel properties of the TRPA1 channel. J Biol Chem 285: 15167–15177, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Story GM, Peier AM, Reeve AJ, Eid SR, Mosbacher J, Hricik TR, Earley TJ, Hergarden AC, Andersson DA, Hwang SW, McIntyre P, Jegla T, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. ANKTM1, a TRP-like channel expressed in nociceptive neurons, is activated by cold temperatures. Cell 112: 819–829, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor-Clark TE, Undem BJ. Sensing pulmonary oxidative stress by lung vagal afferents. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 178: 406–413, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron 21: 531–543, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Buren JJ, Bhat S, Rotello R, Pauza ME, Premkumar LS. Sensitization and translocation of TRPV1 by insulin and IGF-I. Mol Pain 1: 17, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vellani V, Mapplebeck S, Moriondo A, Davis JB, McNaughton PA. Protein kinase C activation potentiates gating of the vanilloid receptor VR1 by capsaicin, protons, heat and anandamide. J Physiol 534: 813–825, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venkatachalam K, Montell C. TRP channels. Annu Rev Biochem 76: 387–417, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vetter I, Cheng W, Peiris M, Wyse BD, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Zheng J, Monteith GR, Cabot PJ. Rapid, opioid-sensitive mechanisms involved in transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 sensitization. J Biol Chem 283: 19540–19550, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang YY, Chang RB, Allgood SD, Silver WL, Liman ER. A TRPA1-dependent mechanism for the pungent sensation of weak acids. J Gen Physiol 137: 493–505, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe N, Horie S, Michael GJ, Keir S, Spina D, Page CP, Priestley JV. Immunohistochemical co-localization of transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV)1 and sensory neuropeptides in the guinea-pig respiratory system. Neuroscience 141: 1533–1543, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zurborg S, Yurgionas B, Jira JA, Caspani O, Heppenstall PA. Direct activation of the ion channel TRPA1 by Ca2+. Nat Neurosci 10: 277–279, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]