Abstract

Background

Excessive intravenous fluid prescription may play a causal role in postoperative complications following major gastrointestinal resectional surgery. The aim of this study was to investigate whether fluid and salt restriction would decrease postoperative complications compared with a more modern controlled liberal regimen.

Methods

In this observer-blinded single-site randomized clinical trial consecutive patients undergoing major gastrointestinal resectional surgery were randomized to receive either a liberal control fluid regimen or a restricted fluid and salt regimen. The primary outcome was postoperative complications of grade II and above (moderate to severe).

Results

Some 240 patients (194 colorectal resections and 46 oesophagogastric resections) were enrolled in the study; 121 patients were randomized to the restricted regimen and 119 to the control (liberal) regimen. During surgery the control group received a median (interquartile range) fluid volume of 2033 (1576–2500) ml and sodium input of 282 (213–339) mmol, compared with 1000 (690–1500) ml and 142 (93–218) mmol respectively in the restricted group. There was no significant difference in major complication rate between groups (38·0 and 39·0 per cent respectively). Median (range) hospital stay was 8 (3–101) days in the controls and 8 (range 3–76) days among those who received restricted fluids. There were four in-hospital deaths in the control group and two in the restricted group. Substantial differences in weight change, serum sodium, osmolality and urine : serum osmolality ratio were observed between the groups.

Conclusion

There were no significant differences in major complication rates, length of stay and in-hospital deaths when fluid restriction was used compared with a more liberal regimen. Registration number: ISRCTN39295230 (http://www.controlled-trials.com).

Introduction

Resectional surgery is a common treatment for most gastrointestinal cancers, both colorectal and oesophagogastric, and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates1,2. The physiological changes and fluid shifts observed in the postoperative phase in this group are complex and vary considerably between patients3. Currently, the prescription of intravenous fluids is often left to more junior members of the medical team, potentially leading to increased risk4. Injudicious use of intravenous fluids, leading to sodium, chloride and water overload, has been suggested to be a major cause of postoperative complications, especially in the presence of co-morbid diseases and advanced age5–7.

Epidural analgesia is frequently used after operation in these surgical patients. One common side-effect of epidural analgesia is hypotension, caused by sympathetic blockade leading to vasodilatation or, particularly with high thoracic epidurals, reduced cardiac sympathetic drive. Such hypotension traditionally is managed by administration of intravenous fluids, which contributes to the fluid load received in the postoperative phase. Conversely, acute kidney injury resulting from hypovolaemia following surgery is also associated with an increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality8.

The evidence base for intravenous fluid therapy is extremely limited, with prescription based on local tradition, expert opinion or extrapolation from trials of fluid resuscitation in patients in shock. Recent trials have attempted to assess the impact of relative intravenous fluid and sodium restriction on outcome after gastrointestinal surgery9–14. However, the control groups in these trials have tended to receive varying amounts and types of intravenous fluid. The volume of intraoperative intravenous fluid administered ranges from 2750 to 5388 ml in control or liberal groups compared with 998 to 2740 ml in restricted groups15.

The aim of this study was to examine the effect of intravenous salt and fluid restriction compared with a more standardized ‘liberal’ fluid therapy on complication rates in major elective gastrointestinal resectional surgery.

Methods

This was a prospective single-centre randomized clinical trial conducted between October 2007 and January 2010. Patients were eligible if aged 18 years or over, and having elective gastrointestinal cancer resection at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital under general anaesthesia with an epidural catheter for intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. In order to study as representative a sample as possible, all gastrointestinal cancer resections such as oesophagectomy, gastrectomy and colonic resections were included, both open and laparoscopic. The study was approved by the Norfolk and Waveney Ethics Committee, the Norfolk Research and Governance Committee.

Exclusion criteria included: American Society of Anesthesiologists grade IV or above, presence of diabetes requiring a specific perioperative fluid regimen, need for preoperative bowel preparation, refusal or contraindication to epidural, planned postoperative ventilation in the intensive care unit, chronic renal failure (defined as serum creatinine level exceeding 140 mmol/l), congestive cardiac failure (New York Heart Association grade 3 or 4), pregnancy, and inability to give informed consent. All patients provided written informed consent before surgery.

Study protocol

After giving consent patients were randomized by an external statistician, using a random number generator with the allocation placed into sealed envelopes that were opened consecutively on the day of surgery. Randomization was to either a restricted (reduced fluid and sodium) study group or a standard (controlled liberal fluids) control group. The operating surgeon was blinded to group allocation until the end of the operation and trial participants were not informed of their randomization group. The study intervention commenced at the start of anaesthesia and continued for 5 days after surgery.

Fluid regimens

All patients were allowed clear fluids as tolerated up to 2 h, and food up to 6 h, before operation. Both groups received 1·5 ml per kg per h maintenance fluid during anaesthesia and operative blood loss was replaced volume for volume with a starch-based colloid. Blood component was replaced according to the haemoglobin level. The control group additionally received a preload with 500 ml Hartmann's solution before placing the epidural, and third-space losses were replaced using Hartmann's solution at 7 ml per kg per h for the first hour followed by 5 ml per kg per h in subsequent hours. The restricted group did not receive any epidural preload or third-space loss replacement. Invasive intraoperative fluid monitoring such as oesophageal Doppler imaging was not used in this trial. The fluid regimen was similar to that used by Brandstrup and colleagues9.

Oral intake was encouraged as much as possible in the postoperative phase in both groups. The colorectal and gastrectomy groups received oral fluids from day 1. Those who underwent oesophagectomy received jejunal feeding via a jejunostomy feeding tube for 4 days, then from day 5 oral fluids were started as tolerated. After operation, the restricted group received intravenous fluid using 5 per cent d-glucose at a rate of 1 ml per kg per h until enteral intake was sufficient. The control group received intravenous fluid at a rate of 1·5 ml per kg per h. The type of fluid given in the control group was departmental standard with a mixture of saline-containing crystalloid and 5 per cent d-glucose to enable a daily input of 1–2 mmol/kg sodium. Electrolytes were monitored daily and replaced in accordance with current practice.

Drain losses above 500 ml/day were replaced with volume for volume starch-based colloid. In both groups, any additional losses over 500 ml/day were replaced with Hartmann's solution volume for volume.

Postoperative hypotension (defined as a drop of more than 30 per cent in systolic pressure from preoperative values) and oliguria (0·3 ml per kg per h or below for 2 h) was treated according to departmental standards in the control group using adjustment of epidural rate, medications and starch-based colloid boluses. In the restricted group and in the absence of shock this was treated by adjustment of the epidural, review of antihypertensive medications and review after 1 h. Persistent hypotension or oliguria in the absence of tachycardia was treated with 3-mg bolus doses of intravenous ephedrine at 5-min intervals, up to a maximum of 15 mg. In the presence of tachycardia a starch-based colloid was also given in 250-ml boluses to achieve an adequate blood pressure and urine output.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was total postoperative complications of grade II and above (moderate to severe)16. Secondary outcome measures were 30-day postoperative mortality, length of postoperative hospital stay, change in forced expiratory volume at 1 s (FEV1) measured by spirometry on day 5 compared with preoperative value, and postoperative hypotensive episodes.

Outcome assessment

Total fluid and sodium composition was quantified for all patients on a daily basis starting with intraoperative volumes, the remaining day of operation until midnight (day 0), and the following 5 days. Serum sodium, osmolality, urea, creatinine, albumin, C-reactive protein and urine osmolality were measured daily. Patients were also weighed daily once able to mobilize to a weighing chair.

Discharge was considered safe and allowed when the patient was mobile, able to self-care and tolerating a light diet. Length of hospital stay was assessed as the postoperative day of discharge.

Complication rates were assessed by two independent, blinded observers by review of medical notes, charts, blood results and radiological investigations. Copies of notes supplied to the observers were screened carefully to exclude mention of randomization group. Complications were graded according to the Accordion classification16. Where the two observers differed in opinion the case was reviewed and a consensus reached.

Statistical analysis

A sample size calculation was performed based on the Brandstrup study9. To achieve 80 per cent power with an α level of 0·05 to detect a decrease in complication rate from 51 per cent in the control group to 33 per cent in the restricted group (18 per cent decrease), the study required 117 patients per group. All patients were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Complication rates were compared between treatment groups using the χ2 test. Owing to the small number of events, 30-day mortality rates were compared using Fisher's exact test. Length of stay and FEV1 were analysed using a t test. Stata® version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station,Texas, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

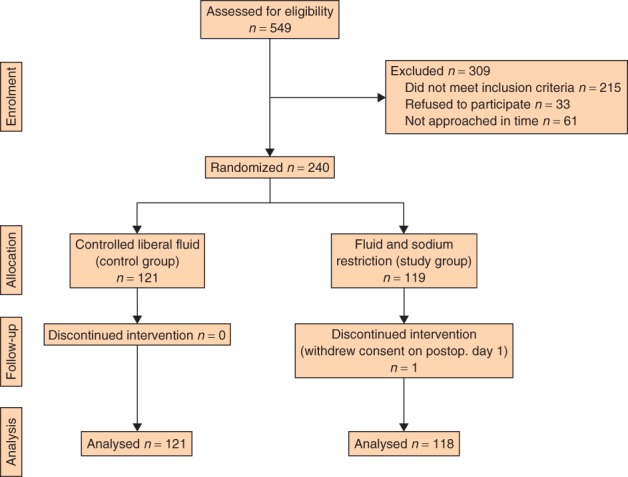

Of 549 patients assessed for eligibility, 240 were randomized (Fig. 1). A total of 309 patients were excluded, of whom 215 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 61 could not be randomized owing to time considerations and 33 declined to participate. Some 121 patients were randomized to the control group (liberal fluid) and 119 patients to the restricted fluid regimen. A total of 194 patients underwent colorectal resection and 46 had an oesophogastric resection. One person in the restricted group withdrew consent after randomization on the first day after surgery. Patient demographics and operative data are shown in Table 1.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram for the trial

Table 1.

Baseline and operative data

| Control (n = 121) | Restriction (n = 118) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 70 (30–94) | 70 (29–88) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | 26 (17–39) | 26 (18–37) |

| Sex ratio (F : M) | 60 : 61 | 44 : 74 |

| ASA fitness grade | ||

| I | 28 (23·1) | 17 (14·4) |

| II | 70 (57·9) | 75 (63·6) |

| III | 23 (19·0) | 26 (22·0) |

| Preop. POSSUM score* | 18 (12–37) | 17 (11–39) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 11 (9·1) | 11 (9·3) |

| Ex-smoker (> 1 year) | 59 (48·8) | 62 (52·5) |

| Non-smoker | 51 (42·1) | 45 (38·1) |

| Alcohol consumption (units/week) | ||

| ≤ 21 | 109 (90·1) | 111 (94·1) |

| > 21 | 12 (9·9) | 7 (5·9) |

| Surgery | ||

| Oesophagectomy | 6 (5·0) | 11 (9·3) |

| Gastrectomy | 17 (14·0) | 12 (10·2) |

| Right colonic resection | 35 (28·9) | 34 (28·8) |

| Left colonic resection | 56 (46·3) | 50 (42·4) |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 6 (5·0) | 9 (7·6) |

| Palliative | 1 (0·8) | 2 (1·7) |

| Surgical approach | ||

| Laparoscopic | 19 (15·7) | 16 (13·6) |

| Open | 102 (84·3) | 102 (86·4) |

| Blood loss (ml)* | 403 (63–2500) | 400 (50–4245) |

| Duration of operation (min)* | 145 (40–285) | 161 (32–343) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range). ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; POSSUM, Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity.

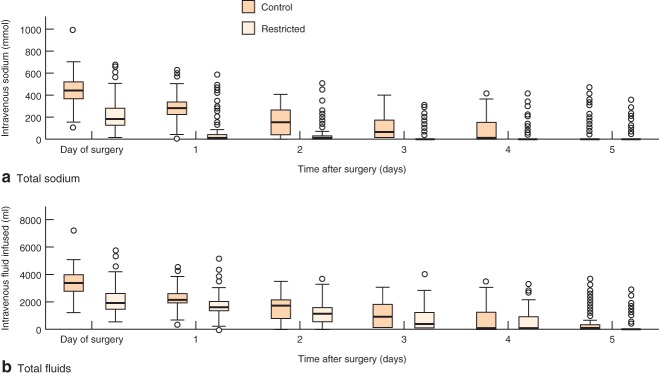

There were large differences in the amount of intravenous salt and total fluid volume infused during surgery. The control group received a median (interquartile range, i.q.r.) intraoperative fluid volume of 2033 (1576–2500) ml and sodium input of 282 (213–339) mmol, compared with 1000 (690–1500) ml and 142 (93–218) mmol respectively in the restricted group. On the day of operation (both during surgery and the remainder of the day), the control group received a median (i.q.r) of 3315 (2645–3894) ml fluid and median sodium input of 449 (352–522) mmol, compared with 1944 (1354–2515) ml and 181 (116–274) mmol in the restricted group. Differences in fluid and sodium input persisted between groups in the postoperative period (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Changes in a intravenous sodium infusion and b total intravenous fluid infusion in the perioperative period. Median (horizontal line within box), interquartile range (box) and range (error bars) are shown

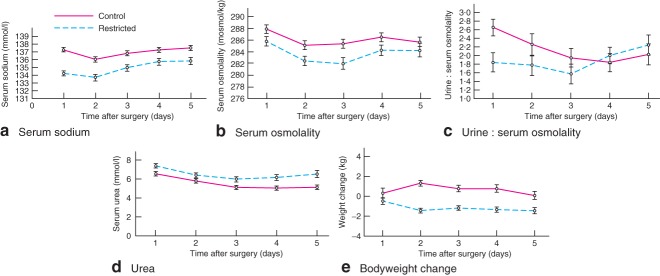

The increased fluid input in the control group was reflected in a mean(s.d.) net weight gain of 1·3(2·4) kg by day 2 after surgery. In contrast, the restricted group had lost 1·4(2·0) kg by day 2 (Fig. 3). Although the control group received more fluid during and after operation, this group had a higher serum osmolality than the restricted group throughout the postoperative period, with a correspondingly higher serum sodium concentration (Fig. 3). The urine : serum osmolality ratio was measured in a smaller cohort of 50 patients; this was higher in the control group for the first 48 h. The serum urea concentration was higher in the restricted group, and was within normal limits.

Fig 3.

Mean(s.e.m.) changes in a serum sodium, b serum osmolality, c urine : serum osmolality ratio and d serum urea, and e mean(s.d.) bodyweight in the postoperative period

Complications

Forty-six patients in each group developed complications of grade II or above (38·0 per cent control versus 39·0 per cent restricted) (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0·959). The 95 per cent confidence interval for the difference in proportions was −0·13 to 0·12, demonstrating that the two fluid regimens were equivalent within a complication rate of 13 per cent, which was below the 18 per cent important clinical difference specified in the protocol. There were no differences in complication rates within any subgroup or complication type, and all were equivalent to the predefined minimally important clinical difference.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Control (n = 121) | Restriction (n = 118) | P‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Major complications | 46 (38·0) | 46 (39·0) | 0·959 |

| Minor complications | 56 (46·3) | 69 (58·5) | 0·080 |

| Cardiac | 12 (9·9) | 6 (5·1) | 0·146 |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (9·1) | 14 (11·9) | 0·512 |

| Neurological | 1 (0·8) | 1 (0·8) | 1·000 |

| Renal | 14 (11·6) | 7 (5·9) | 0·114 |

| Respiratory | 21 (17·4) | 16 (13·6) | 0·386 |

| Vascular | 17 (14·0) | 14 (11·9) | 0·581 |

| Wound | 7 (5·8) | 12 (10·2) | 0·225 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Length of stay (days)* | 8 (7–12) | 8 (6–11) | 0·092§ |

| FEV1 decrease, day 5 (%)† | 26·7(20·6) | 22·1(16·7) | 0·159§ |

| Deaths | 4 (3·3) | 2 (1·7) | 1·000¶ |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (interquartile range);

values are mean(s.d.). FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

χ2 test, except

t test and

Fisher's exact test.

Secondary outcomes

There were four deaths in the control group, all from anastomotic leakage and sepsis after left-sided colonic resection. Two patients died in the restricted group, one from respiratory arrest owing to pneumonia 5 days after total gastrectomy, and one from cardiac arrest secondary to myocardial infarction 6 days after right hemicolectomy. Median length of stay was 8 days in both groups (i.q.r. 7–12, range 3–101 days in control group; i.q.r. 6–11, range 3–76 days in restricted group). The control group had a mean decrease in FEV1 of 26·7 per cent at day 5 compared with 22·1 per cent in the restricted group (P = 0·159). There were 38 episodes of postoperative hypotension (systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg) in the control group compared with 48 in the restricted group (P = 0·094).

Discussion

Intravenous fluid prescription is a commonly overlooked cause of morbidity in surgical patients. The volumes and composition of fluids used in these patients are an area of debate. Traditionally, fluid management has been guided by surrogate measures such as blood pressure, pulse, urine output, and estimates of ‘third space’ and measured losses. This has led to large variations in fluid administration between patients and between centres17,18. Recent studies19,20 have compared alternative strategies for guiding fluid input, including the use of oesophageal Doppler monitoring or other methods of estimating stroke volume variability, or by using more generic protocols for fluid management. It has been suggested that restricting the volume of infused parenteral fluids may be beneficial9,10, although these studies have been criticized for poor regulation of the liberal control groups, manifested as excessively high volumes of infused fluids. This may account for the observed higher complication rates in those groups9. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to compare a fluid-restricted group with a controlled ‘liberal’ fluid group using generic, pragmatic fluid regimens that reflected current practice, typically associated with lower fluid volumes. The main finding of this study was that, compared with a more tightly regulated control group, the measured complications of surgery were unaffected by restricting fluid and salt input.

There were major differences in weight change between the control and restricted groups in the present study, reflecting postoperative fluid retention in the control group with a weight gain of up to 1·5 kg. It has been suggested previously that an increase in weight of 2·5 kg in the postoperative period can be detrimental11. The trigger for postoperative weight gain in the controls may have been mediated by vasopressin secondary to a higher plasma osmolality, as evidenced by the higher urine : serum osmolality ratio in the first 48 h. This was probably secondary to the difference in the type of fluid rather than the volume infused. Thus the study group had a lower serum sodium level and osmolality even though smaller volumes were infused. The use of 0·9 per cent saline in the study group was avoided because of its known deleterious effects21,22. In both groups the amount of fluid used was within the safe range. Fluid balance was monitored daily by weighing, scrutiny of fluid balance charts, and monitoring of blood pressure and pulse.

There were two different groups of operations in this study: upper gastrointestinal resections (oesophagectomy and gastrectomy) and lower gastrointestinal resections. These procedures vary in magnitude, but they did not differ in complications in this study. Even though oesophagogastric and colorectal resections involve different surgical techniques, the associated fluid requirements and complication rates are broadly similar. Although single-lung ventilation is required for most oesophagectomies, the principles of optimizing perianastomotic oxygen delivery and minimizing tissue oedema by means of appropriate intravenous fluid and blood pressure management are essential for all gastrointestinal operations.

Prevention of epidural-associated hypotension by fluid preloading has not been shown to be effective in obstetric patients23,24. Additionally, plasma volume does not increase with thoracic epidural analgesia despite the occurrence of hypotension25. These studies are consistent with the present finding of no difference in the number of postoperative hypotensive episodes between control and fluid-restricted groups. A more logical treatment of epidural-induced hypotension, therefore, might be the administration of vasopressor drugs.

There have been several important changes in the provision of gastrointestinal surgery worldwide, most notably the introduction of laparoscopic surgery, and fast-track recovery (enhanced recovery protocol, ERP), as well as changes in the provision of epidurals and associated anaesthetic techniques26–28. Intravenous fluid prescription varies considerably both between and within centres29. Identification of safe volumes and types of intravenous fluid prescription is important within such a changing surgical and anaesthetic environment. ERPs for both colorectal and upper gastrointestinal procedures commonly use a degree of fluid restriction. The present study also used other ERP components, such as early enteral feeding, minimal drain use, early mobilization and epidural analgesia for all patients. The recent British consensus guidelines on intravenous fluid therapy for adult surgical patients (GIFTASUP)30 provide strong guidance on fluid management in all surgical patients. The present findings suggest that fluid restriction beyond current established fluid restriction protocols, such as that described here, is not beneficial in terms of postoperative outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all surgeons, anaesthetists and ward staff who contributed to the study, and K. Turner and B. Teague for their administrative support. This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research under its Research for Patient Benefit Programme (grant reference no. PB-PG-0706-10478).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jamieson GG, Mathew G, Ludemann R, Wayman J, Myers JC, Devitt PG. Postoperative mortality following oesophagectomy and problems in reporting its rate. Br J Surg. 2004;91:943–947. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bokey EL, Chapuis PH, Fung C, Hughes WJ, Koorey SG, Brewer D, et al. Postoperative morbidity and mortality following resection of the colon and rectum for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:480–486. doi: 10.1007/BF02148847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shires T, Williams J, Brown F. Acute change in extracellular fluids associated with major surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 1961;154:803–810. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196111000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh SR, Walsh CJ. Intravenous fluid-associated morbidity in postoperative patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:126–130. doi: 10.1308/147870805X28127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lobo DN, Macafee DA, Allison SP. How perioperative fluid balance influences postoperative outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20:439–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arieff AI. Fatal postoperative pulmonary oedema: pathogenesis and literature review. Chest. 1999;115:1371–1377. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowell JA, Schifferdecker C, Driscoll DF, Benotti PN, Bistrian BR. Postoperative fluid overload: not a benign problem. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:728–733. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Praught ML, Shlipak MG. Are small changes in serum creatinine an important risk factor? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14:265–270. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000165894.90748.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandstrup B, Tønnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R, Hjortsø E, Ørding H, Lindorff-Larsen K, et al. Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on postoperative complications: comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens a randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238:641–648. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094387.50865.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G, Weissman C, Einav S, Matot I. Effect of intraoperative fluid management on outcome after intra-abdominal surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lobo DN, Bostock KA, Neal KR, Perkins AC, Rowlands BJ, Allison SP. Effect of salt and water balance on recovery of gastrointestinal function after elective colonic resection: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1812–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacKay G, Fearon K, McConnachie A, Serpell MG, Molloy RG, O'Dwyer PJ. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of postoperative intravenous fluid restriction on recovery after elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1469–1474. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holte K, Foss NB, Andersen J, Valentiner L, Lund C, Bie P, et al. Liberal or restrictive fluid administration in fast-track colonic surgery: a randomized, double-blind study. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:500–508. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermeulen H, Hofland J, Legemate DA, Ubbink DT. Intravenous fluid restriction after major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded clinical trial. Trials. 2009;10:50. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Secher NH, Kehlet H. ‘Liberal’ vs. ‘restrictive’ perioperative fluid therapy—a critical assessment of the evidence. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The Accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177–186. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181afde41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majid AA, Kingsnorth AN. Fundamentals of Surgical Practice. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkitt HG, Quick CRG. Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis and Management. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh SR, Tang T, Bass S, Gaunt ME. Doppler-guided intra-operative fluid management during major abdominal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:466–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandstrup B, Svendsen PE, Rasmussen M, Belhage B, Rodt SÅ, Hansen B, et al. Which goal for fluid therapy during colorectal surgery is followed by the best outcome: near-maximal stroke volume or zero fluid balance? Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:191–199. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheingraber S, Rehm M, Sehmisch C, Finsterer U. Rapid saline infusion produces hyperchloremic acidosis in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1265–1270. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid F, Lobo DN, Williams RN, Rowlands BJ, Allison SP. (Ab)normal saline and physiological Hartmann's solution a randomized double-blind crossover study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:17–24. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubli M, Shennan AH, Seed PT, O'Sullivan G. A randomised controlled trial of fluid pre-loading before low dose epidural analgesia for labour. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2003;12:256–260. doi: 10.1016/S0959-289X(03)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamilselvan P, Fernando R, Bray J, Sodhi M, Columb M. The effects of crystalloid and colloid preload on cardiac output in the parturient undergoing planned cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia a randomized trial. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1916–1921. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181bbfdf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holte K, Foss NB, Svensén C, Lund C, Madsen JL, Kehlet H. Epidural anesthesia, hypotension, and changes in intravascular volume. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:281–286. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200402000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller S, Zalunardo MP, Hubner M, Clavien PA, Demartines N Zurich Fast Track Study Group. A fast-track program reduces complications and length of hospital stay after open colonic surgery. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:842–847. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kehlet H. Fast-track surgery—an update on physiological care principles to enhance recovery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:585–590. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0790-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kehlet H, Mogensen T. Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation programme. Br J Surg. 86:227–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoneham MD, Hill EL. Variability in post-operative fluid and electrolyte prescription. Br J Clin Pract. 1999;51:82–84. 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powell-Tuck J, Gosling P, Lobo DN, Allison SP, Carlson GL, Gore M, et al. British Consensus Guidelines on Intravenous Fluid Therapy for Adult Surgical Patients (GIFTASUP) Redditch: British Society for Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition; 2011. [Google Scholar]