Abstract

Background

Emergency laparotomies in the UK, USA and Denmark are known to have a high risk of death, with accompanying evidence of suboptimal care. The emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle is an evidence-based care bundle for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy, consisting of: initial assessment with early warning scores, early antibiotics, interval between decision and operation less than 6 h, goal-directed fluid therapy and postoperative intensive care.

Methods

The ELPQuiC bundle was implemented in four hospitals, using locally identified strategies to assess the impact on risk-adjusted mortality. Comparison of case mix-adjusted 30-day mortality rates before and after care-bundle implementation was made using risk-adjusted cumulative sum (CUSUM) plots and a logistic regression model.

Results

Risk-adjusted CUSUM plots showed an increase in the numbers of lives saved per 100 patients treated in all hospitals, from 6·47 in the baseline interval (299 patients included) to 12·44 after implementation (427 patients included) (P < 0·001). The overall case mix-adjusted risk of death decreased from 15·6 to 9·6 per cent (risk ratio 0·614, 95 per cent c.i. 0·451 to 0·836; P = 0·002). There was an increase in the uptake of the ELPQuiC processes but no significant difference in the patient case-mix profile as determined by the mean Portsmouth Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity risk (0·197 and 0·223 before and after implementation respectively; P = 0·395).

Conclusion

Use of the ELPQuiC bundle was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death following emergency laparotomy.

Introduction

Emergency laparotomy is a common surgical procedure undertaken for a wide variety of acute intra-abdominal conditions1. In England, it is estimated that one in 1100 of the population undergoes an emergency laparotomy each year2. Successive National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death analyses have found poor standards of care. In 2010, the Emergency Laparotomy network (ELN)3 collected data from 35 hospitals and reported a crude 30-day hospital mortality rate of 14·9 (range 3·6–41·7) per cent, rising to 24·4 per cent in patients aged 80 years and over. A larger retrospective analysis4 from the USA of 37 553 patients showed a similarly high mortality rate of 14 per cent. Most recently, a large prospective study5 of 4920 patients undergoing emergency laparotomy in Denmark reported a 19·5 per cent mortality rate. In the UK there is increasing recognition that outcomes after emergency major general surgery are poor and would benefit from standardization of care6–9.

The ELN report also highlighted wide variation in, and poor delivery of, a number of key process indicators that are supported in evidence-based clinical guidelines10. These included lack of surgical and anaesthetic consultant involvement, and the underuse of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy and postoperative intensive care3.

A care-bundle approach to implementation of key evidenced-based components of care was adopted. The care-bundle concept was developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in 200111. Two commonly used and successful applications of this approach are the care bundles developed to reduce central venous catheter-line infection and to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia11. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign12 has used the care-bundle concept to improve dramatically the outcomes of patients presenting with sepsis.

The aim of this study was to compare risk-adjusted 30-day mortality after emergency laparotomy before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle, within the context of a multicentre quality improvement project.

Methods

This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for the reporting of quality improvement work13.

This project was an assessment of current practice and implementation of best-practice guidelines. The UK National Research Ethics Service confirmed that formal ethical approval was not required. The project was approved by the research and development department, audit department or institutional review board in each hospital.

Development of the bundle

Following submission of data from one hospital to the ELN, the authors developed an evidence-based care bundle for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. This was based on key recommendations made in the Royal College of Surgeons of England and Department of Health publications10,14. Recommendations with a strong evidence base were adopted into the care bundle. The elements of the bundle and the evidence on which they are based are: all emergency admissions have an early warning score assessed on presentation, with graded escalation policies for senior clinical and intensive care unit (ICU) referral (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline 5015); broad-spectrum antibiotics to be given to all patients with suspicion of peritoneal soiling or with a diagnosis of sepsis (Surviving Sepsis Campaign12,16,17); once the decision has been made to carry out laparotomy, the patient takes the next available place in the emergency theatre (or within 6 h of decision being made)10; start resuscitation using goal-directed techniques as soon as possible, or within 6 h of admission (NICE recommendation and others18–20); and admit all patients to the ICU after emergency laparotomy5,21,22.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To allow meaningful national comparison, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted from those used by the ELN for their national audit (Table S1, supporting information)3.

Setting and collaboration

The ELPQuiC bundle was implemented in four National Health Service (NHS) hospitals. In each hospital the lead clinician formed a multidisciplinary implementation group, and executive board-level acceptance was confirmed. The specific details of the quality improvement strategies were left to the discretion of the local implementation groups, but followed the ‘plan, do, study, act’ approach23. Identifying the specific set of problems, and working out successful solutions at a local level was seen to be an important part of the study. Although the local specifics varied, methods of implementation included poster, e-mail and education campaigns to promote ELPQuiC, regular presentation of project data and individual patients to key care-provider groups, and development of specific mechanisms to ensure prompt sepsis management, radiological investigations and theatre prioritization.

During the 8-month project, representatives from each site met every 6 weeks. Improvement techniques, successful strategies and challenges were discussed and shared.

Data collection and verification

The data set and definitions were agreed before the start of the project. Each hospital employed one person responsible for day-to-day collection of data. Queries or omissions were dealt with by the clinical lead at each hospital. If further clarification was required, issues were discussed either at project meetings or directly with principal investigators. Anonymized data were entered by each hospital into the Electronic Database for Global Education (EDGE; Clinical Informatics Research Unit, Southampton General Hospital, UK; http://www.edge.nhs.uk). Cross-checking of data was carried out at each hospital between the lead clinician and data collector.

Each hospital submitted ELPQuiC baseline data before implementation on consecutive patients for a minimum of 3 months before the start of the project. These data sets consisted of a combination of existing databases and additional retrospective data collection. The ELPQuiC bundle was introduced simultaneously in all four hospitals in December 2012. Data were collected from all eligible consecutive patients over 8 months.

Predicted mortality was estimated for each patient using the Portsmouth modification of the Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity (P-POSSUM)24. Data collected included demographics and compliance with bundle elements. The primary outcome was P-POSSUM risk-adjusted 30-day mortality.

The database was searched for missing or anomalous data. An additional 10 per cent of data were checked randomly for accuracy. Missing data were due to non-availability or poor documentation. Feedback on crude 30-day mortality and bundle compliance was reported to each site on a regular basis using run charts.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the cohort were described for each hospital using patient age, sex, P-POSSUM risk, American Society of Anesthesiologists fitness grade, mortality and length of hospital stay. The uptake of the ELPQuiC bundle was compared by percentage. Crude mortality and risk-adjusted 30-day mortality data were reported and analysed. In-hospital mortality was analysed separately. Two statistical approaches were used based on the predicted risk of death for each patient calculated using the P-POSSUM equation. From each of these analyses individual hospital and pooled results were calculated with 95 per cent c.i. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·050.

In the first approach, cumulative sum (CUSUM) plots were used to show the cumulative difference between expected risk of death (as defined by case mix-adjusted P-POSSUM score) and observed outcome (0, alive; 1, died). An increasing CUSUM reflects the saving of lives, a decreasing CUSUM reflects loss of lives, and a stable CUSUM is neutral. Separate CUSUM plots were produced for each hospital showing the results before and after the ELPQuiC implementation periods. The CUSUM slopes (before versus after) were compared using a single linear regression model with CUSUM as the response variable, hospital as an indicator variable and baseline as a binary variable (yes/no), with consecutive patient number as an interaction term. The coefficient of the interaction term is the difference in slopes (difference in lives saved per patient) before versus after implementation. This statistical analysis provided insight into the pace of change.

In the second approach, a binary logistic regression model was used to compare overall risk-adjusted mortality in the intervals before and after implementation of the care bundle. The response variable was 30-day mortality, and the P-POSSUM risk (on the logit scale) was used as an offset term. A single model was constructed with an indicator variable for hospital, a binary variable indicating baseline (yes/no), and an interaction term between hospital and baseline period. The interaction term represents the difference in log odds of death between the baseline and ELPQuiC periods. The results from the logistic regression model were represented as absolute risks, risk differences and risk ratios using the approach described by Norton and colleagues25.

The risk profile of patients before and after implementation of the ELPQuiC bundle was compared using the mean P-POSSUM risk of death, individually for each hospital and collectively for all hospitals using a test for proportions.

The statistical significance of changes in process-of-care variables was determined using a two-tailed Fisher's exact test with missing data treated as a separate category, and also with the missing data excluded from the calculations, so that the extent to which missing data contributed to the change could be assessed. All analyses were undertaken using Stata® Release 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) and R (http://www.R-project.org).

Results

In the interval before implementation of the ELPQuiC bundle, 299 consecutive patients underwent emergency laparotomy compared with 427 consecutive patients in the 8 months following introduction of the bundle. Table 1 shows the demographic data before and after implementation in each hospital. There was no significant difference in the risk profile of patients as determined by the P-POSSUM risk in any hospital or pooled across all hospitals. The pooled P-POSSUM risk in the baseline period was 0·197, compared with 0·223 after implementation (risk difference –0·026, 95 per cent c.i. –0·086 to 0·034; P = 0·395) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and outcomes of patients before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle

| Site 1 |

Site 2 |

Site 3 |

Site 4 |

All patients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ELPQuiC (n = 51) | After ELPQuiC (n = 109) | Before ELPQuiC (n = 144) | After ELPQuiC (n = 144) | Before ELPQuiC (n = 44) | After ELPQuiC (n = 97) | Before ELPQuiC (n = 60) | After ELPQuiC (n = 77) | Before ELPQuiC (n = 299) | After ELPQuiC (n = 427) | |

| Age (years)* | 66·6(16·6) | 65·3(17·7) | 65·1(16·6) | 63·7(17·5) | 65·7(13·9) | 69·3(14·0) | 66·2(15·0) | 66·0(15·5) | 65·6(15·8) | 65·8(16·5) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| F | 38 (75) | 56 (51·4) | 73 (50·7) | 79 (54·9) | 19 (43) | 49 (51) | 31 (52) | 41 (53) | 161 (53·8) | 225 (52·7) |

| M | 13 (25) | 53 (48·6) | 71 (49·3) | 65 (45·1) | 25 (57) | 48 (49) | 29 (48) | 36 (47) | 138 (46·2) | 202 (47·3) |

| Outcome at 30 days | ||||||||||

| Alive | 42 (82) | 96 (88·1) | 123 (85·4) | 126 (87·5) | 39 (89) | 89 (92) | 53 (88) | 71 (92) | 257 (86·0) | 382 (89·5) |

| Dead | 9 (18) | 13 (11·9) | 21 (14·6) | 18 (12·5) | 5 (11) | 8 (8) | 7 (12) | 6 (8) | 42 (14·0) | 45 (10·5) |

| Died in hospital | ||||||||||

| No | 41 (80) | 96 (88·1) | 122 (84·7) | 125 (86·8) | 37 (84) | 89 (92) | 52 (87) | 70 (91) | 252 (84·3) | 380 (89·0) |

| Yes | 10 (20) | 13 (11·9) | 22 (15·3) | 19 (13·2) | 7 (16) | 8 (8) | 8 (13) | 7 (9) | 47 (15·7) | 47 (11·0) |

| ASA fitness grade | ||||||||||

| I | 5 (10) | 14 (12·8) | 12 (8·3) | 16 (11·1) | 4 (9) | 8 (8) | 6 (10) | 7 (9) | 27 (9·0) | 45 (10·5) |

| II | 10 (20) | 36 (33·0) | 48 (33·3) | 52 (36·1) | 9 (21) | 32 (33) | 28 (47) | 27 (35) | 95 (31·8) | 147 (34·4) |

| III | 19 (37) | 40 (36·7) | 46 (31·9) | 44 (30·6) | 18 (41) | 40 (41) | 20 (33) | 32 (42) | 103 (34·5) | 156 (36·5) |

| IV | 16 (31) | 18 (16·5) | 31 (21·5) | 26 (18·1) | 12 (27) | 12 (12) | 5 (8) | 10 (13) | 64 (21·4) | 66 (15·5) |

| V | 1 (2) | 1 (0·9) | 7 (4·9) | 6 (4·2) | 1 (2) | 5 (5) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 10 (3·3) | 13 (3·0) |

| Length of hospital stay (days)† | 11 (7–24) | 11 (7–21) | 12 (7–23) | 10 (6–18) | 12 (8–21) | 12 (8–19) | 10 (7–21) | 13 (6–32) | 11 (7–23) | 11 (6–21) |

| P-POSSUM risk score* | 0·226(0·282) | 0·251(0·298) | 0·193(0·234) | 0·267(0·307) | 0·200(0·207) | 0·179(0·241) | 0·179(0·237) | 0·159(0·212) | 0·197(0·239) | 0·223(0·278) |

| P‡ | 0·730 | 0·140 | 0·764 | 0·755 | 0·395 | |||||

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.) and

median (i.q.r.) for survivors. ELPQuiC, emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; P-POSSUM, Portsmouth modification of Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity.

Test for proportions.

The overall crude 30-day mortality rate decreased from 14·0 (95 per cent c.i. 10·1 to 18·0) per cent (42 of 299 patients) in the baseline interval to 10·5 (7·6 to 13·5) per cent (45 of 427) following implementation of the care bundle. The reduction in crude mortality was 3·5 (–1·4 to 8·4) per cent (P = 0·152).

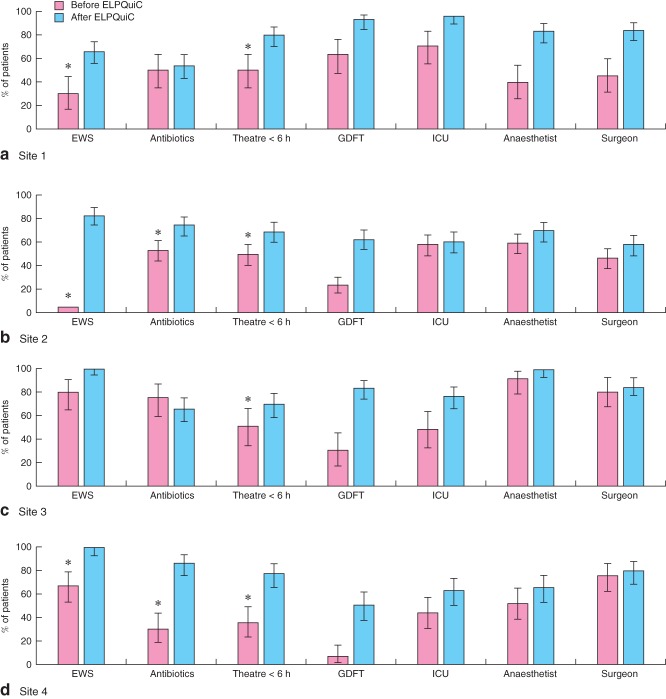

Mortality outcomes were adjusted for individual patients' predicted risk of 30-day mortality. Fig. 1 shows expected minus observed CUSUM charts for each hospital. In three hospitals there was a significant increase in lives saved per 100 patients treated after introduction of the ELPQuiC care bundle (Table 2). When patients from all hospitals were pooled, an additional 5·97 patients per 100 treated survived beyond 30 days after emergency laparotomy following the introduction of the ELPQuiC bundle (P < 0·001).

Figure 1.

Cumulative sum analysis before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle: a site 1, b site 2, c site 3 and d site 4

Table 2.

Lives saved (before 30 days) per 100 patients before and after introduction of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle

| Lives saved per 100 patients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Before ELPQuiC | After ELPQuiC | Difference | P* |

| 1 | 6·48 (4·64, 8·32) | 11·96 (11·37, 12·55) | 5·48 (3·55, 7·42) | < 0·001 |

| 2 | 6·76 (6·37, 7·14) | 15·68 (15·29, 16·06) | 8·92 (8·37, 9·47) | < 0·001 |

| 3 | 7·95 (5·66, 10·25) | 9·96 (9·26, 10·67) | 2·01 (–0·40, 4·42) | 0·101 |

| 4 | 4·34 (2·90, 5·78) | 8·77 (7·78, 9·76) | 4·43 (2·68, 6·19) | < 0·001 |

| All | 6·47 (5·79, 7·15) | 12·44 (12·14, 12·75) | 5·97 (5·23, 6·72) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i. ELPQuiC, emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care.

Linear regression model.

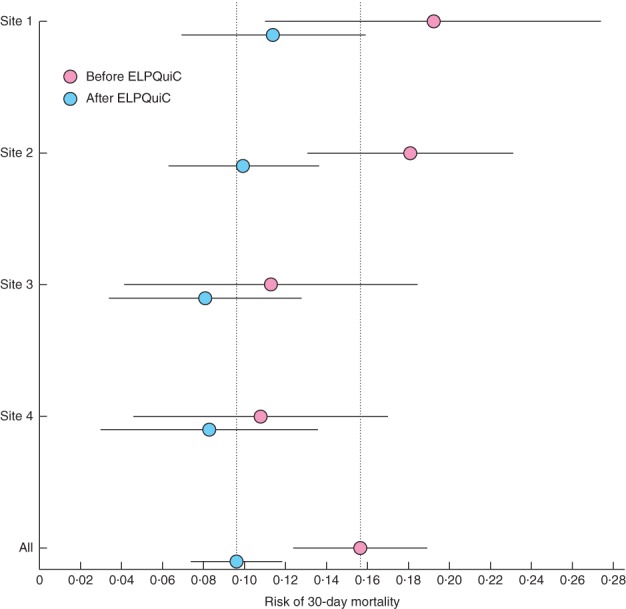

The P-POSSUM-adjusted risk of death at 30 days is shown in Fig. 2 and Table 3. The pooled adjusted risk of 30-day mortality decreased from 15·6 (95 per cent c.i. 12·4 to 18·9) to 9·6 (7·4 to 11·8) per cent (P = 0·003). The number of patients who need to be treated using the ELPQuiC bundle in order to save an additional life was 16·7. The pooled risk ratio was 0·614 (95 per cent c.i. 0·451 to 0·836; P = 0·002).

Figure 2.

Risk of 30-day mortality before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle. Error bars represent 95 per cent c.i.

Table 3.

Risk of 30-day mortality before and after introduction of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle

| Risk of death |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Before ELPQuiC | After ELPQuiC | Risk difference | P* | Risk ratio | P† |

| 1 | 0·192 (0·110, 0·274) | 0·114 (0·070, 0·159) | –0·078 (–0·171, 0·015) | 0·101 | 0·595 (0·334, 1·059) | 0·078 |

| 2 | 0·181 (0·131, 0·231) | 0·100 (0·063, 0·136) | –0·081 (–0·143, –0·020) | 0·010 | 0·550 (0·348, 0·869) | 0·010 |

| 3 | 0·113 (0·042, 0·184) | 0·081 (0·034, 0·128) | –0·032 (–0·117, 0·053) | 0·462 | 0·716 (0·304, 0·169) | 0·445 |

| 4 | 0·108 (0·046, 0·170) | 0·083 (0·030, 0·136) | –0·025 (–0·106, 0·056) | 0·542 | 0·766 (0·326, 1·803) | 0·542 |

| All | 0·156 (0·124, 0·189) | 0·096 (0·074, 0·118) | –0·060 (–0·100, –0·021) | 0·003 | 0·614 (0·451, 0·836) | 0·002 |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i. ELPQuiC, emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care.

Logistic regression model;

P value for loge of the risk ratio (logistic regression model).

An analysis was carried out using in-hospital mortality as the outcome (Tables S2–S4, Figs S1 and S2, supporting information). When the patients from all hospitals were pooled, an additional 8·11 (95 per cent c.i. 7·42 to 8·81) patients per 100 treated survived to hospital discharge after introduction of the ELPQuiC bundle (P < 0·001). The pooled adjusted risk of hospital mortality decreased from 17·4 (95 per cent c.i. 14·1 to 20·8) to 10·1 (7·8 to 12·4) per cent (P < 0·001).

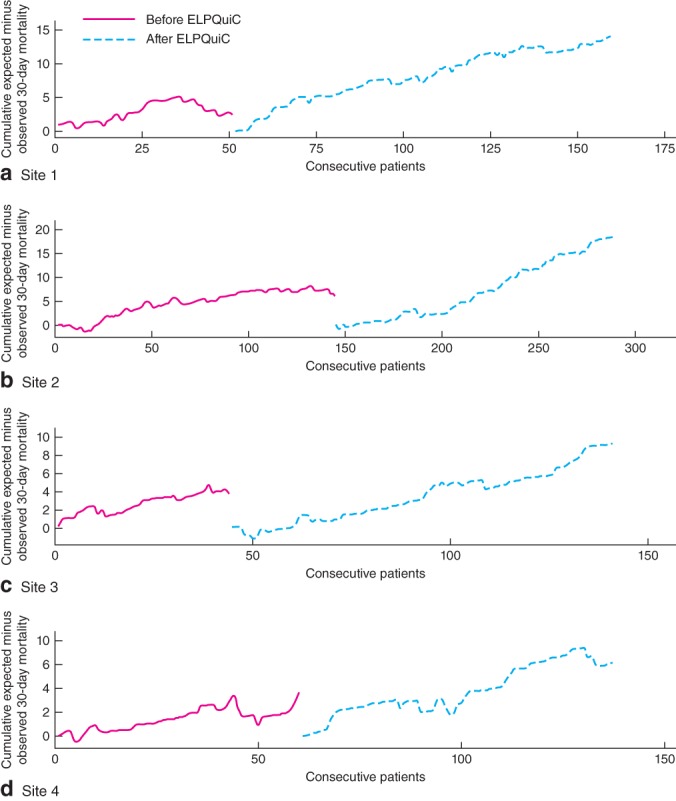

Fig. 3 and Table S5 (supporting information) show process measures in use before and after implementation of the ELPQuiC bundle. Some of the process data were not recorded routinely before the project and were therefore collected retrospectively. Table S5 details proportions of unavailable data. The change in goal-directed fluid therapy was statistically significant at all sites (P < 0·001). The change in ICU was statistically significant in three of the four sites. Although not specifically part of the ELPQuiC bundle, the change in senior clinicians' involvement is also reported in Table S5.

Figure 3.

Compliance with processes of care before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle: a site 1, b site 2, c site 3 and d site 4. Error bars represent 95 per cent c.i. *More than 15 per cent of data not available. EWS, early warning score; GDFT, goal-directed fluid therapy; ICU, intensive care unit

Discussion

In this multicentre collaboration, the introduction of a five-component care bundle, augmented by senior clinical input during operations, led to a significant reduction in P-POSSUM risk-adjusted 30-day mortality. Individually, three of the four hospitals showed a statistically significant improvement in the P-POSSUM-adjusted CUSUM 30-day mortality rate after bundle implementation, with 5·97 more lives saved per 100 patients treated overall compared with outcomes before implementation of the ELPQuiC bundle. P-POSSUM-adjusted CUSUM analysis of in-hospital mortality demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in all four hospitals individually, with 8·11 lives saved per 100 patients treated overall. These results were achieved within existing resources, without adversely affecting the length of hospital stay, while the case-mix profile remained relatively stable.

Only one hospital achieved statistical significance in the binary regression analysis of risk of 30-day mortality. This suggests a lack of power or sample size, as the underlying trend from the CUSUM plot was favourable and highly significant for the combined data. Overall, risk difference and risk ratio analysis demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in both 30-day and in-hospital mortality after the introduction of ELPQuiC.

High mortality rates have been described after emergency laparotomy, and guidelines to improve outcomes have been developed3–5,10,14. Implementation of the ELPQuiC bundle and demonstration of improved outcomes in four different hospitals, all with their own unique contexts, provides evidence of external validity of the use of this approach to reduce mortality after emergency laparotomy. Locally developed and adapted interventions have been described as necessary to sustain effective change26. All four hospitals improved in different process areas to different degrees. This probably reflects the diversity of practice across hospitals.

Some of the process measures before implementation of the ELPQuiC bundle were not collected prospectively. For some data (such as ICU admission), this was easily collected retrospectively, whereas information on other variables (for example interval between decision to perform laparotomy and operating theatre) was difficult to collect accurately from patient records. For this reason, some of the processes had an incomplete data rate of more than 15 per cent. Some hospitals were highly compliant with some aspects of the care bundle before the official launch, and so there was less room for improvement, and statistically significant changes were unlikely in practice with these samples sizes. However, significant changes in both the use of goal-directed fluid therapy and admission to ICU were found across almost all of the participating sites. These two elements of the bundle may have the greatest impact in reducing mortality in other hospitals and healthcare systems where these standards of care are not met routinely.

The direct involvement of senior surgeons and anaesthetists in patient care was significantly improved at one hospital. Trends for improvement, albeit not statistically significant, were seen at the other sites.

Measurement alone is known to drive improvement. Transparency and regular audit have been shown to lead to better outcomes in surgery26. The regular measurement of outcome and process measures, and the understanding of areas for better performance, are likely to have aided improvement in this project and are central to quality improvement methodology.

A standard pathway approach, as used in enhanced recovery programmes, has been shown to be successful in reducing hospital stay and complications when applied to elective surgical procedures27. In this study a similar standard approach was applied to the emergency setting. However, length of stay was not reduced in this study. A number of factors may explain this, including the survival of patients who would not previously have survived surgery and the availability of suitable discharge facilities.

There are limitations to this study. The patient groups before implementation of the care bundle were of unequal size and not collected during the same time intervals. There are no contemporaneous controlled comparisons with other hospitals not involved in the ELPQuiC project. However, the findings are suggestive of a credible underlying link between observed improvements in processes of care and subsequent risk-adjusted mortality.

The extent to which the bundles are now embedded as routine care has yet to be evaluated. All hospitals in England and Wales are now required to submit data to the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit28. This will assist ongoing performance analysis and quality improvement.

This study has used quality improvement methodology to implement an evidence-based care bundle, in a variety of hospital settings, which has reduced risk-adjusted mortality after emergency laparotomy. Standardization of care, following simple evidence-based guidelines, such as ELPQuiC, should be considered in all hospitals undertaking emergency laparotomy.

Acknowledgments

The ELPQuiC Collaborator Group was formed from four acute Trusts in England. The group is grateful to the hard-working staff in all these hospitals who were able to implement the ELPQuiC bundle so effectively.

Funding from the Health Foundation was provided to all hospitals (Shine Grant 2012). Baseline data collection at the Royal United Hospital Bath was funded by an Innovation grant from the South West Strategic Health Authority. LiDCO Group (London, UK) provided LiDCOrapid cardiac output monitors, consumables and education at all sites, depending on local experience and requirements. LiDCO Group was not involved in any project discussions, protocol design, meetings or data analysis.

Collaborators

V. Hemmings, A. Riga, A. Belguamkar, M. Zuleika, D. White (Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford); L. Corrigan, T. Howes, S. Richards, S. Dalton, T. Cook, R. Kryztopik (Royal United Hospital Bath, Bath); A. Cornwell, J. Goddard, S. Grifiths, F. Frost, A. Pigott (Torbay Hospital, Torquay); J. Pittman, L. Cossey, N. Smart, I. Daniels (Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter).

Disclosure

N.Q. was funded by LIDCO to deliver a lecture to its enhanced recovery summit in Brussels, Belgium, March 2013. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1 Risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality risk: cumulative sum plot (Word document)

Fig. S2 Risk of in-hospital mortality before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle (Word document)

Table S1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Word document)

Table S2 In-hospital deaths (Word document)

Table S3 Lives saved (before hospital discharge) per 100 patients before and after introduction of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle (Word document)

Table S4 Risk of in-hospital mortality before and after introduction of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle (Word document)

Table S5 Process measures before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle (World document)

References

- 1.Shafi S, Aboutanos MB, Agarwal S, Brown CVR, Crandall M, Feliciano DV, et al. AAST Committee on Severity Assessment and Patient Outcomes. Emergency general surgery: definition and estimated burden of disease. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1092–1097. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827e1bc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapter SL, Paul MJ, White SM. Incidence and annual cost of emergency laparotomy in England: is there a major funding shortfall? Anaesthesia. 2012;67:474–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.07046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders DI, Murray D, Pichel AC, Varley S, Peden CJ. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: the first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Temimi MH, Griffee M, Enniss TM, Preston R, Vargo D, Overton S, et al. When is death inevitable after emergency laparotomy? Analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vester-Andersen M, Lundstrøm LH, Møller MH, Waldau T, Rosenberg J, Møller AM, Danish Anaesthesia Database Mortality and postoperative care pathways after emergency gastrointestinal surgery in 2904 patients: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:860–870. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huddart S, Peden C, Quiney N. Emergency major abdominal surgery – ‘the times they are a-changing’. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:645–649. doi: 10.1111/codi.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergenfelz A, Søreide K. Improving outcomes in emergency surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e1–e2. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoneham M, Murray D, Foss N. Emergency surgery: the big three – abdominal aortic aneurysm, laparotomy and hip fracture. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:70–80. doi: 10.1111/anae.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peden CJ. Emergency surgery in the elderly patient: a quality improvement approach. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:435–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Surgeons of England, Department of Health. The Higher Risk General Surgical Patient: Towards Improved Care for a Forgotten Group. 2011. http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/higher-risk-surgical-patient/ [accessed 1 March 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resar R, Griffin FA, Haraden C, Nolan TW. Using Care Bundles to Improve Health Care Quality. 2012. IHI Innovation Series white paper; http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/UsingCareBundles.aspx [accessed 1 March 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc G, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(Suppl 1):i3–i9. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029066. SQUIRE Development Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Emergency Surgery. Standards for Unscheduled Surgical Care. 2011. http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/emergency-surgery-standards-for-unscheduled-care [accessed 1 March 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Acutely Ill Patients in Hospital: Recognition of and Response to Acute Illness in Adults in Hospital. 2007. NICE Clinical Guideline 50; http://www.nice.org.uk/CG50 [accessed 1 March 2014] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, Linde-Zwirble WT, Marshall JC, Bion J, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1738-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, Roberts D, Light B, Parrillo JE, et al. Cooperative Antimicrobial Therapy of Septic Shock Database Research Group Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest. 2009;136:1237–1248. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearse R, Dawson D, Fawcett J, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Early goal-directed therapy after major surgery reduces complications and duration of hospital stay. A randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN38797445] Crit Care. 2005;9:R687–R693. doi: 10.1186/cc3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) CardioQ-ODM Oesophageal Doppler Monitor. NICE Medical Technology Guidance 3; 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/MTG3 [accessed 1 March 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grocott MP, Dushianthan A, Hamilton MA, Mythen MG, Harrison D, Rowan K, Optimisation Systematic Review Steering Group Perioperative increase in global blood flow to explicit defined goals and outcomes after surgery: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:535–548. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearse RM, Harrison DA, James P, Watson D, Hinds C, Rhodes A, et al. Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Crit Care. 2006;10:R81. doi: 10.1186/cc4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Symons NR, Moorthy K, Almoudaris AM, Bottle A, Aylin P, Vincent CA. Mortality in high-risk emergency general surgical admissions. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1318–1325. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langley GL, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CLPL. The Improvement Guide: a Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prytherch D, Whiteley M. POSSUM and Portsmouth POSSUM for predicting mortality. Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1217–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton EC, Miller MM, Kleinman LC. Computing adjusted risk ratios and risk differences in Stata. Stata J. 2001;13:492–509. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson A, Lowe MC, Parker J, Lewis SR, Alderson P, Smith AF. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in surgical patients. Br J Surg. 2014;101:172–188. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) http://www.nela.org.uk [accessed 1 March 2014]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality risk: cumulative sum plot (Word document)

Fig. S2 Risk of in-hospital mortality before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care (ELPQuiC) bundle (Word document)

Table S1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Word document)

Table S2 In-hospital deaths (Word document)

Table S3 Lives saved (before hospital discharge) per 100 patients before and after introduction of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle (Word document)

Table S4 Risk of in-hospital mortality before and after introduction of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle (Word document)

Table S5 Process measures before and after implementation of the emergency laparotomy pathway quality improvement care bundle (World document)