Abstract

Objective

To assess the relief of migraine pain, especially in the acute phase, by comparing active treatment, ie, kinetic oscillation stimulation (KOS) in the nasal cavity, with placebo.

Background

Exploratory trials testing the efficacy of KOS on migraine patients indicated that this treatment could be a fast-acting remedy for acute migraine pain.

Method

Thirty-six patients were randomized 1:1 using a placebo module to active or placebo treatment in this double-blinded parallel design study. Treatment was administered with a minimally invasive inflatable tip oscillating catheter. Symptom scores (0–10 visual analog scale) were obtained before treatment, every 5 minutes during treatment, at 15 minutes, 2, and 24 hours post-treatment, as well as daily (0–3 migraine pain scale) from 30 days pretreatment until Day 60 post. Thirty-five patients were evaluated (active n = 18, placebo n = 17). The primary end-point was the change in average pain score from before treatment to 15 minutes after treatment.

Results

Patients who received active treatment reported reduced pain, eg, average visual analog scale pain scores fell from 5.5 before treatment to 1.2 15 minutes after, while the corresponding scores for recipients of placebo fell from 4.9 to 3.9. The changes in pain scores differed between the 2 treatments by 3.3 points (95% confidence interval: 2.3, 4.4), P < .001. Already 5 minutes into the treatment, the difference (1.9 points) was significant (P = .007). The difference was likewise significant at 2 hours post-treatment (3.7 points, P < .001). One patient experienced an adverse event (a vasovagal reaction with full spontaneous recovery) during placebo treatment.

Conclusion

KOS is an effective and safe treatment for acute migraine pain.

Keywords: migraine, neuromodulation, autonomic nervous system, kinetic oscillation stimulation, minimally invasive, medical device

Migraine is a chronic neurovascular disorder characterized by episodes of head pain that may be severe.1 Triptans are widely used to treat acute migraine, but on average only 59% of patients experience relief at 2 hours, 29% of patients are free of pain 2 hours after dose, and only 20% remain pain-free 24 hours after drug administration.2

A fast-acting injectable triptan can promote some relief at 15 minutes post-injection, with pain relief increasing up to 2 hours post-injection.3 Triptans should be administered early during an attack in order to have the best treatment effect.4,5

The sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) is located 2–9 mm beneath the nasal mucosa.6,7 Administration of intranasal lidocaine in the region of the SPG has been reported to bring significant pain relief to migraineurs within a few minutes. During an ongoing attack, 35.8% of patients reported pain relief at 15 minutes (7.4% placebo), although the rate for lidocaine efficacy was less than that seen with triptans.6 The medical device system used in this study can deliver kinetic oscillation stimulation (KOS) inside the nasal cavity close to the SPG. A similar device system was used for a previous study on non-allergic rhinitis.8

Exploratory single treatments on a number of patients with migraine promoted both a rapid reduction in experienced acute pain and a reduction in pain intensity and attack frequency during subsequent weeks and months in some cases. Starting intranasal treatment on the initial symptom side appeared advantageous to the treatment results. Subsequently treating the other side seemed to further improve treatment outcomes.

Based on these promising results, the present randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind parallel group clinical pilot study was performed under controlled conditions on a cohort of patients with migraine, with the objective of further evaluating any superiority of KOS to placebo on acute migraine pain. We hypothesized that KOS treatment in a placebo-controlled study would exhibit some or all of the same improvements seen in the exploratory treatments, with the null hypothesis that there would be no difference between the groups.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Patients were recruited using advertisements in the local press. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) and who signed a written informed consent form were invited to participate. Almost all patients had a family history of migraine. Before the study began, they were also examined clinically by a neurologist (R.G.H.) and an ear, nose and throat specialist (J.-E.J.). Thirty-six patients at one site (Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm) were randomized in this double-blind parallel design study. The study was approved by the ethics committee at the Karolinska Institute, Stock holm, on May 5, 2013. The study was registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01880671).

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

|

| Exclusion Criteria |

|

CNS = central nervous system; ICHD-2 = International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition.

KOS Treatment System

The treatment was administered using a minimally invasive system conceived by the clinical investigator. It consisted of a controller and a single-use catheter (Fig. 1), as well as a placebo module (CT100) and a headband (E100) from Chordate Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden. The controller was connected to the CT100, and the CT100 in turn to the catheter. The E100 was used to secure the position of the catheter. The catheter, with a coating of lubricating paraffin, was inserted into the nasal cavity (Fig. 2), on the side with the predominant pain (if applicable). For active treatment, the tip was inflated and oscillated for 15 minutes at 95 millibar pressure and 68 Hz frequency. After 15 minutes, the oscillations stopped (for active treatment). The catheter was deflated and moved to the other side, reinflated (for active treatment), and treatment (active or placebo) continued for another 15 minutes. The settings and treatment duration were based on the experience obtained from prior exploratory treatments.

Fig 1.

Treatment catheter in plastic bag.

Fig 2.

Catheter inserted into nasal cavity and secured with headband.

Each CT100 module had a unique internal code allowing 3 out of every 6 consecutive patients to receive active treatment, with the other 3 receiving a placebo treatment where the catheter neither inflated nor oscillated. Group assignment was thus determined solely by the hidden coding in the CT100 and the order in which patients were treated, with no other restrictions applied, and with a 1:1 allocation ratio. This means that all treatments were performed with a CT100 connected between the controller and the catheter. The administration of placebo or active treatment was blinded to the patients as no patients were familiar with the treatment and knew what to expect. Before the trial, a general description of the treatment with a nasal catheter was given. The patients were informed that one of 2 covering gels would be used (in reality, both where paraffin), but they were not informed about the details of the procedure or its effects, if any. The clinical investigator was also blinded during the trial since he could not tell, as the catheters were inserted so far into the nasal cavity, whether or not the intranasal catheter was inflated or if it oscillated. The controller operated in the same manner for both treatments.

It has been stated that it is nearly impossible to devise effective sham treatments in trials using neuromodulation as the stimulation is always perceived.9 However, the visual appearance of the vibrating controller (its enclosure and the connected tubes show minor vibrations) and the sound generated during both types of procedures, as well as the covering lubricating gel used, most likely concealed the true nature of the active and placebo treatments from the patients. The results were based on reported self-assessed symptom scores, which means that those who assessed outcomes were also blinded. A new CT100 was used for every 6 patients, and the coding of each module was unknown to the clinical investigator (coding kept secret by manufacturer).

Statistical Considerations

The power analysis was conducted based on the secondary end-point of share of patients with 50% improvement following treatment, as anecdotal evidence was available for this parameter from previous trials but not for the primary end-point. In these previous trial procedures, >85% of patients with acute migraine reported a pain reduction of at least 50% on a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS) pain scale in direct association with KOS treatment. Assuming a pain reduction in 70% of cases with active treatment (a more conservative estimate compared with the previous trials) and 20% for placebo, a 2-sided alpha level of 0.05, and a power of 0.9, the groups should have 19 patients each. It was, therefore, considered that evaluating the response of 40 patients to treatment would be sufficient to assess the potential efficacy of KOS to relieve acute migraine pain.

The high-resolution VAS and short recording intervals during the procedures were chosen in order to provide optimal information on the possible effects of the treatment. The levels of VAS pain were analyzed by a 2-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Analyses at specific time points were made using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with the baseline value as a covariate. The treatment group differences were tested at the 0.05 alpha level.

A 2-sided chi-square test at the 0.05 alpha level was used to analyze whether or not the secondary end-points were achieved. Bonferroni-adjusted P values were calculated to control for type I errors in the repeated assessments.

Missing data points at 2 and 24 hours (patients unwilling to provide data) were imputed in an ancillary intention-to-treat analysis using last observations carried forward as these were the best available estimates for each patient. The intention-to-treat analysis was intended to control for different response rates in the active and placebo groups.

The code was broken by the statistician after the datasets were completed and locked. The statistician performed the study sizing, calculated the descriptive statistics, and performed statistical tests. The statistical analyses were performed using version 9.4 of the SAS System under Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Schedule of Events

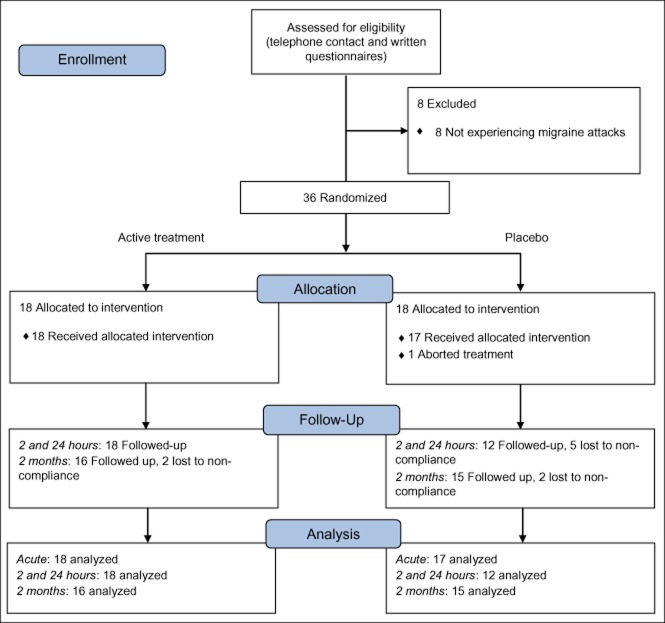

On their first visit, the patients were first clinically investigated. They received a paper diary with instructions to make daily notes of any migraine attacks, their length, intensity, and medication use, when applicable. Forty-four patients were selected for the study and passed this step (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

CONSORT flow diagram.

After 30 days, patients were ready for treatment. If typical signs of an attack with or without aura developed, the patient contacted the clinical investigator by phone. It was determined whether the attack fulfilled the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition criteria (including 0–10 VAS of at least 4.0), and if met treatment was administered within 20 minutes of arrival at the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge. It took patients at least one hour to get to the hospital following the phone call, and the patients were all at least 2 hours into their attacks at the time of treatment. Patients were asked not to take any medication before the study treatment. During the trials, the patients recorded their level of pain with a pencil on paper marked with a 0–10 VAS scale, where 0 represented no pain and 10 unbearable pain (no intermediate steps marked). The scorings were done just before treatment, every 5 minutes during treatment, at completion of the treatment and 15 minutes after treatment, each time on a new piece of paper. Many patients in both the active and the placebo groups blew their noses after the treatment. All patients were asked about their general well-being immediately following all the VAS recordings. They all stayed for about 30 minutes after treatment before leaving the hospital.

The level of pain at 2 and 24 hours were recorded on a 0–10 VAS scale using telephone interviews conducted by the clinical investigator following treatment.

Only one treatment session, with either placebo or active treatment, was administered to each patient as part of the study. After treatment, patients were asked to continue with daily diary entries for 60 days.

The first patient was enrolled on May 20, 2013. The last patient was enrolled on September 23, 2013. (The last enrolled patient did not complete the study.) The first patient was treated on June 17, 2013. The last patient was treated on October 3, 2013.

End-Points

Acute Treatment

The primary efficacy end-point in the study was to evaluate the change in average pain score on the VAS scale from just prior to treatment to 15 minutes after the completion of treatment (ie, 45 minutes after onset of stimulation). As secondary end-points, pain relief rate (at least 50% reduction in pain score9) and pain-free rate (<1.0 VAS) in the patient groups were also considered. The same metrics were also considered at 2 and 24 hours after treatment.

Two-Month Follow-Up

The change in the number of headache days one month prior to treatment and 2 months following treatment was considered a secondary end-point, as was average attack duration in hours and attack intensity (0–3 scale) at the same time points.

Results

Patient Population

Thirty-six patients were included in the study (Fig. 3) after experiencing migraine attacks and fulfilling the inclusion criteria (with exceptions as described below), 29 females and 7 males, aged 20–61. Randomization of patients stopped 4 patients short of the targeted 40 patients as the inflow of patients from the pool of 44 experiencing attacks slowed. Two patients older than 55 years were included in the analysis (the set upper age limit was based on the assumption that older patients would respond less favorably to treatment). Five of the patients either did not experience migraine attacks during the run-in period or failed to present completed diaries, but were nevertheless included in the analysis as their typical disease profiles fit the inclusion criteria.

Eleven of the patients did not meet the inclusion criterion of having a VAS pain score before treatment of 4.0 or higher, even though they did meet this criterion when they called in before heading to the hospital. It was, therefore, decided to include these patients in the analysis.

Summary statistics for historic migraine attack frequency and characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics of Historic Migraine Characteristics

| Count, Except for Age | Active | % | Placebo | % | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Average (years) | 44.2 (43.4) | N/A | 44.6 (46.0) | N/A | 44.4 (44.7) | N/A |

| Gender | Male | 4 (1) | 22 | 3 (1) | 17 | 7 (2) | 19 |

| Female | 14 (4) | 78 | 15 (4) | 83 | 29 (8) | 81 | |

| Recurrent headache since | <20 years | 5 (0) | 28 | 5 (0) | 28 | 10 (0) | 28 |

| ≥20 years | 13 (1) | 72 | 13 (0) | 72 | 26 (1) | 72 | |

| Attacks per week | <1 | 9 (1) | 50 | 9 (0) | 50 | 18 (1) | 50 |

| ≥1 | 7 (0) | 39 | 7 (2) | 39 | 14 (2) | 39 | |

| Variable attack frequency | 2 (0) | 11 | 2 (0) | 11 | 4 (0) | 11 | |

| Duration of attack | ≤1 day | 9 (2) | 50 | 6 (4) | 33 | 15 (6) | 42 |

| 1–3 days | 5 (2) | 28 | 7 (1) | 39 | 12 (3) | 33 | |

| ≥3 days | 2 (0) | 11 | 1 (0) | 6 | 3 (0) | 8 | |

| Variable attack frequency | 2 (0) | 11 | 4 (0) | 22 | 6 (0) | 17 | |

| Predominantly unilateral pain | Yes | 16 (1) | 89 | 15 (0) | 83 | 31 (1) | 86 |

| No | 2 (1) | 11 | 3 (0) | 17 | 5 (1) | 14 | |

All participating patients had a diagnosed migraine according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition. Some patients did not fully fill out the pretreatment questionnaires. Data pertaining to these 10 patients were completed through telephone interviews during the study. In the columns above, the number of patients whose data were completed through such interviews is indicated within parentheses.

Eighteen patients received active treatment and were available for analysis of efficacy in the acute phase, as were 17 who received placebo. One patient experienced an adverse event during the procedure (a vasovagal reaction with full spontaneous recovery within a few minutes) and treatment was aborted. This patient belonged to the placebo group and was not included in the analyses. No other adverse reactions were reported. Data for all 18 patients in the active group were also collected regarding the experienced pain level at 2 and 24 hours post-treatment, as were corresponding reports from 12 of the placebo patients (the other 5 were unwilling to participate. Data for these patients was imputed in an ancillary analysis, Table 4). Follow-up data were available for 16 and 15 patients in the active and placebo treatment groups, respectively.

Table 4.

Summary Statistics for Secondary End-Points (2 and 24 Hours Post-Treatment)

| Group | Time Point | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD Change From Baseline | 50% Pain Relief Rate | P Value* vs Placebo | Pain-Free Rate | P Value* vs Placebo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active (n = 18) | Before | 5.5 ± 1.5 | |||||

| 15 minutes after | 1.2 ± 1.0 | −4.3 ± 1.5 | 17 | P < .001 | 9 | P = .063 | |

| 94% | P* < .001 | 50% | P* = .51 | ||||

| 2 hours | 1.3 ± 1.9 | −4.2 ± 2.3 | 16 | P < .001 | 9 | P = .018 | |

| 89% | P* < .001 | 50% | P* = .14 | ||||

| 24 hours | 1.2 ± 2.5 | −4.3 ± 2.6 | 15 | P = .13 | 14 | P = .114 | |

| 83% | P* = 1.00 | 78% | P* = .91 | ||||

| 24 hours sustained | 14 | P = .001 | 8 | P = .035 | |||

| 78% | P* = .008 | 44% | P* = .28 | ||||

| Placebo (n = 12) | Before | 4.7 ± 2.4 | |||||

| 15 minutes after | 3.6 ± 2.0 | –1.2 ± 1.4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 17% | 17% | ||||||

| 2 hours | 4.9 ± 3.0 | 0.2 ± 2.1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 17% | 8% | ||||||

| 24 hours | 1.9 ± 2.5 | –2.8 ± 4.4 | 7 | 6 | |||

| 58% | 50% | ||||||

| 24 hours sustained | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 17% | 8% |

The P* values are Bonferroni-adjusted P values for 8 tests.

Patients with data available for both 2 and 24 hours only. “24 Hours Sustained” denotes improvements at both 2 and 24 hours.

Note that rescue medication use following the 15-minute post-measurement and before 24 hours in the placebo group was higher (76%) compared with the active treatment group (17%).

Placebo rates with imputation using LOCF for 15 minutes after, 2 hours, 24 hours, 24 hours sustained:

50% pain relief: 3 (18%) P < .001, 3 (18%) P < .001, 9 (53%) P = .053, 3 (18%) P < .001.

Pain-free: 2 (12%) P = .015, 1 (6%) P = .004, 7 (41%) P = .027, 1 (6%) P = .009.

The corresponding Bonferroni adjusted for 8 tests P values are for 50% pain relief: P* < .001. P* < .001, P* = .42, and P* = .003, respectively; and for pain-free: P* = .12, P* = .031, P* = .22, and P* = .073, respectively.

LOCF = last observations carried forward; SD, standard deviation.

Primary End-Point: Attack Treatment

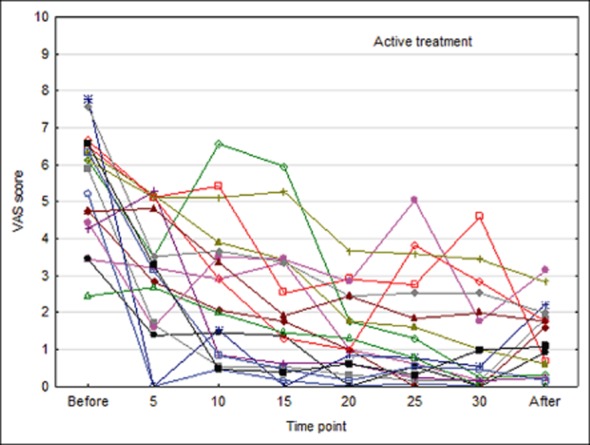

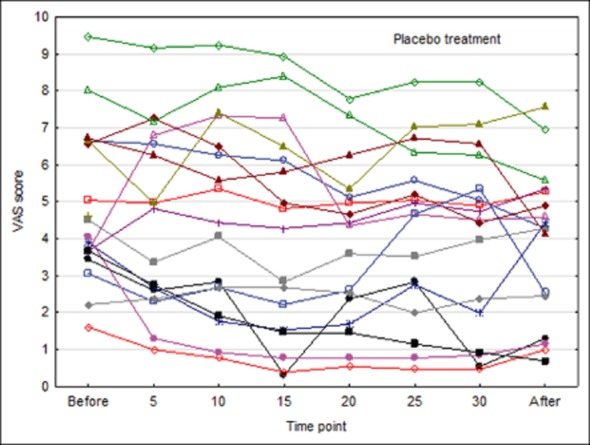

KOS treatment using the Chordate system reduced pain score during a migraine attack from a mean of 5.5 on the VAS scale before treatment to 1.2 at 15 minutes post-treatment, a change of 4.3 units (95% confidence interval [CI]: −5.0, −3.6), see Table 3. The corresponding change for placebo treatment was from 4.9 to 3.9, a change of 1.0 unit (95% CI: −1.8, −0.2). The changes in pain scores differed between the 2 treatments by 3.3 points (95% CI: 2.3, 4.4), P < .001. Individual VAS scores for all 35 analyzed patients are presented in Figures 4 and 5.

Table 3.

Summary Statistics of VAS Pain Scores by Treatment Group and Time Point

| Group | Time Point | N | Mean ± SD Absolute | Mean ± SD Change From Baseline | 95% CI | Mean ± SD Percent Change From Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Before | 18 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | |||

| 5 minutes into treatment | 18 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | −2.3 ± 2.2 | (−3.4, −1.2) | −38.0 ± 34.7 | |

| 10 minutes into treatment | 18 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | −2.8 ± 2.1 | (−3.9, −1.8) | −49.6 ± 32.3 | |

| 15 minutes into treatment | 18 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | −3.4 ± 2.3 | (−4.5, −2.3) | −59.3 ± 32.6 | |

| 20 minutes into treatment | 18 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | −4.1 ± 1.7 | (−4.9, −3.3) | −74.0 ± 21.0 | |

| 25 minutes into treatment | 18 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | −4.0 ± 1.9 | (−4.9, −3.1) | −72.9 ± 28.4 | |

| 30 minutes into treatment (end of treatment) | 18 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | −4.3 ± 1.5 | (−5.1, −3.6) | −80.9 ± 22.3 | |

| 15 minutes post | 18 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | −4.3 ± 1.5 | (−5.0, −3.6) | −78.7 ± 18.7 | |

| Placebo | Before | 18 | 4.9 ± 2.1 | |||

| 5 minutes into treatment | 17 | 4.5 ± 2.4 | −0.4 ± 1.3 | (−1.0, 0.3) | −8.9 ± 33.0 | |

| 10 minutes into treatment | 17 | 4.6 ± 2.6 | −0.3 ± 1.5 | (−1.0, 0.4) | −8.2 ± 39.4 | |

| 15 minutes into treatment | 17 | 4.1 ± 2.8 | −0.8 ± 1.6 | (−1.6, 0.0) | −20.8 ± 46.1 | |

| 20 minutes into treatment | 17 | 3.9 ± 2.2 | −1.0 ± 1.1 | (−1.6, −0.4) | −22.6 ± 29.6 | |

| 25 minutes into treatment | 17 | 4.2 ± 2.3 | −0.6 ± 1.3 | (−1.3, 0.0) | −14.8 ± 35.8 | |

| 30 minutes into treatment (end of treatment) | 17 | 4.0 ± 2.4 | −0.9 ± 1.5 | (−1.7, −0.1) | −19.2 ± 43.2 | |

| 15 minutes post | 17 | 3.9 ± 2.1 | −1.0 ± 1.6 | (−1.8, −0.2) | −18.8 ± 35.1 |

CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation; VAS = visual analog scale.

Fig 4.

Individual visual analog scale (VAS) scores by minute during procedure in patients receiving active treatment.

Fig 5.

Individual visual analog scale (VAS) scores by minute during procedure in patients receiving placebo treatment.

Mean baseline score was slightly higher in the active group as compared with the placebo group (t-test P = .34), but this did not significantly affect the results. With active treatment, a continuous decrease in mean score over time was observed, which still remained at the assessment 15 minutes after end of therapy. In the placebo group, a minor decrease from baseline was observed at corresponding time points, with virtually no change from 15 minutes into the KOS treatment to end of treatment.

Statistical testing using repeated ANOVA measures demonstrated a significant difference between groups when including all data points (absolute values: P = .002, change from baseline: P < .001). Separate ANCOVA comparisons with the baseline value as covariate at the time points 15 minutes post-treatment (primary end-point; baseline adjusted difference: 3.0) and 30 minutes (end of treatment) demonstrated significantly lower absolute values and a larger decrease from baseline for the group receiving active treatment (P < .001 for all comparisons).

Treatment was started on the right side in 16 of the analyzed patients and on the left side in 19 patients. Results were comparable for both sequences with statistically significant results similar to the results for all patients combined. Pain levels fell further when active treatment was continued on the other side.

Some of the patients in the study were included even though they did not meet the inclusion criterion of having at least a 4.0 VAS score at the beginning of treatment. Twenty-four of the 36 patients in the study did meet this criterion. All patients with 4.0 or more on the VAS pain scale before treatment and who received active treatment had 3.1 or less on the VAS scale following treatment. All patients with VAS 4.0 or more who received placebo treatment scored VAS 4.0 or more following treatment, with the exception of one outlying patient. The difference in reduced pain (3.6 on VAS Scale) achieved by active treatment compared with placebo from baseline before treatment to 15 minutes after treatment was significant (P < .001) using an ANCOVA model with the baseline value as covariate.

Secondary End-Points

Seventeen out of 18 (94%) patients in the active group experienced at least 50% pain relief at 15 minutes after termination of treatment compared with just before treatment, as did 3 of 17 (18%) patients in the placebo group. Nine out of 18 (50%) patients in the active group were pain-free at 15 minutes post-treatment compared with 2 out of 17 (12%) for the placebo group. End-point metrics for patients who reported data for both 2 and 24 hours post-treatment are presented in Table 4.

The number of days during the 2 months of follow-up when patients experienced migraine pain fell slightly in the active group compared with the situation during the run-in period. Correspondingly, the proportion of headache days increased in the placebo group, with a similar pattern during both months, but the difference was not significant (P = .39 run-in to first month of follow-up, P = .53 to the second).

The pain intensity and attack duration tended to decrease in the active group compared with the placebo group during the first month of follow-up (P = .42 and P = .37, respectively).

An ancillary, exploratory analysis showed that the baseline attack frequency fell sharply during the run-in period with a sharp upturn toward the end of the run-in period. This was possibly due to a combination of weather and seasonal atmospheric conditions, as well as the beneficial influence of the traditional summer holidays on patients who had an opportunity to relax and recuperate during the summer. Treatments were mostly administered around the time when holidays had just ended.

Rescue medication following treatment was used by 3/18 (17%) patients in the active group and 13/17 (76%) in the placebo group, suggesting that the improvement in the active group was clinically meaningful.

The null hypothesis for the single primary end-point was rejected. The null hypothesis was also rejected for 50% pain relief rate following Bonferroni adjustment at 15 minutes after, 2 hours after, and 24 hours sustained (Table 4).

Discussion

The differences in VAS pain scores during treatment between the groups receiving active treatment and placebo were statistically significant for all time points combined, for the slope of change over time, and for separate comparisons at end of treatment and after treatment. With active therapy, onset of reduction in experienced pain intensity was rapid, with a statistically significant decrease already after 5 minutes of KOS treatment (the changes in pain scores differed between the 2 treatments by 1.9 points on VAS scale, ANCOVA analysis similar to that for primary end-points: P = .007), comparing favorably with the effects of fast-acting injectable triptan.3

Since treatment was offered at the hospital, patients were typically several hours into their migraine attacks when KOS was administered. Late drug administration is typically associated with worse treatment results in migraine studies,4,5 but the beneficial pain-relieving effects of the active procedure used in this study were still quite strong, even after several hours of migraine.

Results at 2 and 24 hours sustained after treatment showed strong both clinically (at least 50% improvement on VAS scale) and statistically significant improvements in the active compared with the placebo group. The relative lack of both pain relief and pain freedom in the placebo group would be expected to occur and has also been demonstrated in earlier studies testing other migraine therapies.10

The 2-month follow-up data failed to demonstrate any clinically significant beneficial long-term prophylactic outcome of the active procedure. The relatively small sample size for this type of analysis (as opposed to acute response for which the study was sized), and the strong seasonality in the attack incidence during the run-in period, where there seemed to be a seasonal pattern of increasing attacks commencing around the time of the treatments in the study and the start of the follow-up period, possibly contributed to the findings not being significant. Further studies during other times of the year would be desirable.

One patient receiving placebo therapy experienced an adverse event with full spontaneous recovery. Overall, the treatment was well tolerated.

Patients were recruited for the study through advertising in a local newspaper. It cannot be excluded that there could have been some self-selection of patients dissatisfied with their current treatment results or side effects.

Some patients forgot to bring their run-in diaries to the hospital and failed to send their diaries later, leading to gaps in the collected material. Others, especially in the placebo group, failed to present follow-up diaries. Acute data (for the primary end-point) were available for all patients but the one who experienced an adverse event.

The study was performed at one university hospital clinic. Further and extended investigations at multiple locations should ideally be performed.

Kinetic oscillations in the nasal cavity stimulate the mucosa and possibly activate sensory nerve endings with afferents in the trigeminal nerve. The known trigeminal parasympathetic autonomic reflex seems to be involved in some types of migraine attacks.11,12 Migraine is a complex disorder with several neuronal pathways and neurotransmitters involved in the pathophysiology, but the hypothalamus which has widespread connections with other parts of the central nervous system and its paramount control of the autonomic nervous system is believed to play a key part in migraine.13 The SPG supplies the nasal mucosa and has connections to the hypothalamus, as the ganglion receives parasympathetic fibers from the superior salivatory nucleus, which in turn receives input from the hypothalamus,14 and has been suggested as a target for neurostimulation.15 The superior salivatory nucleus is at the heart of the trigeminal autonomic reflex.16 Electrical SPG stimulation can promote improvements in primary headaches,14,17 suggesting that stimulation mediated through the above connections could be connected to headache relief. Indirect SPG stimulation through the nasal cavity could be a pathway that perhaps explains some of the results of this study.

We speculate that KOS, at least in part, may mitigate migraine symptoms through the trigeminal parasympathetic reflex and an associated beneficial impact on autonomic balance. The results obtained in this study are not inconsistent with such an idea. We conclude that KOS is a potentially beneficial non-pharmacological treatment option for patients with migraine headache.

Conclusions

The pilot study is the first known controlled trial of treatment of acute migraine using kinetic oscillations administered in the nasal cavity. The treatment promoted a statistically and clinically significant reduction in the reported average pain level during treatment and 2 hours after, suggesting that KOS could possibly be a treatment alternative for acute migraine attacks. The treatment provided a statistically significant better reduction in pain in the active group compared with the placebo group already 5 minutes from the start of treatment. Improvement in the active group compared with placebo was not significant during the 2-month follow-up period. Further exploration of the longer term effects of the procedure could be considered.

Acknowledgments

Anders Ljungström, BSc, Progstat AB, for conducting statistical analysis.

Glossary

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CI

confidence interval

- ICHD-2

International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition

- KOS

kinetic oscillation stimulation

- SD

standard deviation

- SPG

sphenopalatine ganglion

- VAS

visual analog scale

Statement of Authorship

Category 1

(a) Conception and Design

Jan-Erik Juto; Rolf G. Hallin

(b) Acquisition of Data

Jan-Erik Juto; Rolf G. Hallin

(c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data

Jan-Erik Juto; Rolf G. Hallin

Category 2

(a) Drafting the Manuscript

Jan-Erik Juto; Rolf G. Hallin

(b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

Jan-Erik Juto; Rolf G. Hallin

Category 3

(a) Final Approval of the Completed Manuscript

Jan-Erik Juto; Rolf G. Hallin

References

- 1.Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine – Current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:257–270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, Roon KI, Lipton RB. Triptans (serotonin, 5-HT1B/1D agonists) in migraine: Detailed results and methods of a meta-analysis of 53 trials. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:633–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cady RK, Aurora SK, Brandes JL. Satisfaction with and confidence in needle-free subcutaneous sumatriptan in patients currently treated with triptans. Headache. 51:1202–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lantéri-Minet M, Mick G, Allaf B. Early dosing and efficacy of triptans in acute migraine treatment: The TEMPO study. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:226–235. doi: 10.1177/0333102411433042. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Láinez M. Clinical benefits of early triptan therapy for migraine. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:24–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maizels M, Geiger AM. Intranasal lidocaine for migraine: A randomized trial and open-label follow-up. Headache. 1999;39:543–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3908543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sluder G. The anatomical and clinical relations of the sphenopalatine (Meckel's) ganglion to the nose and its accessory sinuses. NY Med J. 1909;28:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juto JE, Axelsson M. Kinetic oscillation stimulation as treatment of non-allergic rhinitis: An RCT study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134:506–512. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2013.861927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martelletti P, Jensen RH, Antal A. Neuromodulation of chronic headaches: Position statement from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain. 2013;14:86. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tfelt-Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: Third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:6–38. doi: 10.1177/0333102411417901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avnon Y, Nitzan M, Sprecher E, Rogowski Z, Yarnitsky D. Different patterns of parasympathetic activation in uni- and bilateral migraineurs. Brain. 2003;126:1660–1670. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB. A review of paroxysmal hemicranias, SUNCT syndrome and other short-lasting headaches with autonomic feature, including new cases. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 1):193–209. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alstadhaug KB. Migraine and the hypothalamus. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:809–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn S, Schoenen J, Ashina M. Sphenopalatine ganglion neuromodulation in migraine: What is the rationale? Cephalalgia. 2014;34:382–391. doi: 10.1177/0333102413512032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins B, Tepper SJ. Neurostimulation for primary headache disorders, part 1: Pathophysiology and anatomy, history of neuromodulation in headache treatment, and review of peripheral neuromodulation in primary headaches. Headache. 2011;51:1254–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akerman S, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Diencephalic and brainstem mechanisms in migraine. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:570–584. doi: 10.1038/nrn3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenen J, Højland Jensen R, Lantéri-Minet M. Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for cluster headache treatment. Pathway CH-1: A randomized, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:816–830. doi: 10.1177/0333102412473667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]