To the editors:

Central nervous system primitive neuro-ectodermal tumours (CNS-PNETs) are a group of rare childhood embryonal brain tumours associated with a poor prognosis (approximately 50% overall survival) and defined by a common histology according to the current consensus World Health Organisation (WHO) classification [7]. CNS-PNETs occur supratentorially and are defined by histological features shared with cerebellar PNETs (termed medulloblastomas), however the histological classification of CNS-PNET can be challenging. Individual CNS-PNETs are often reclassified as other paediatric supratentorial tumour groups, including anaplastic astrocytoma, atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumour (ATRT), anaplastic oligodendroglioma and anaplastic ependymoma, following central immunophenotypic and histological review [3, 12]. Initial studies have shown that substantial molecular heterogeneity exists within CNS-PNETs; molecular features characteristic of other cerebral brain tumour types (e.g. IDH1 mutation, CDKN2A deletion) have been detected in subsets, but unifying genomic defects have not yet been reported [4, 8, 10, 11].

The recent definition of embryonal tumours with abundant neuropil and true rosettes (ETANTR) as a discrete tumour entity occurring in very young children within the CNS-PNET group - characterised by focal amplification of 19q13.42 and dismal outcome [5, 6, 9] - suggests the existence of currently unrecognised molecular pathological variants, and a refined understanding of CNS-PNET biology could lead to their improved subclassification and the subsequent development of directed therapies.

We and others have recently demonstrated the utility of DNA methylation profiling for the discovery and distinction of clinical and molecular sub-classes of brain tumour types including medulloblastomas, gliomas and ependymomas [13-15]. To investigate the potential of DNA methylation profiles to enhance the molecular classification of CNS-PNETs, we assessed 1505 CpG residues across 807 genes in a series of 29 archival CNS-PNETs using established methods [14], alongside assessment of clinical and molecular characteristics (Figure 1h). All biopsies underwent central neuropathological review according to WHO criteria [7] by a three pathologist panel (TSJ, KR and JL). Tumours representing ETANTRs, CNS-PNETs with significant glial (GFAP) or neuronal (synaptophysin) differentiation, and SMARCB1/INI1-negative tumours (by immunohistochemistry (IHC)), were excluded and not assessed, thus defining a study population of morphologically homogeneous CNS-PNETs for analysis (Figure 1a). Finally, DNA methylation profiles from 136 further paediatric brain tumours were generated contemporaneously and assessed in comparison. These included medulloblastomas of defined molecular subgroup (n=60; 15 representative examples each from the WNT (MBWNT), SHH (MBSHH), Group 3 (MBGroup3) and Group 4 (MBGroup4) [14]), alongside ependymomas (n=61; 45 posterior fossa (16 anaplastic, 29 classic; median age at diagnosis, 2.8 years), 16 supratentorial (9 anaplastic, 7 classic; median age, 6.9 years)) and cerebral high-grade gliomas (pHGG; n=15; 12 glioblastoma multiforme, 3 anaplastic astrocytoma; median age 7.1 years) with histology confirmed by central histological review (by WHO criteria [7]).

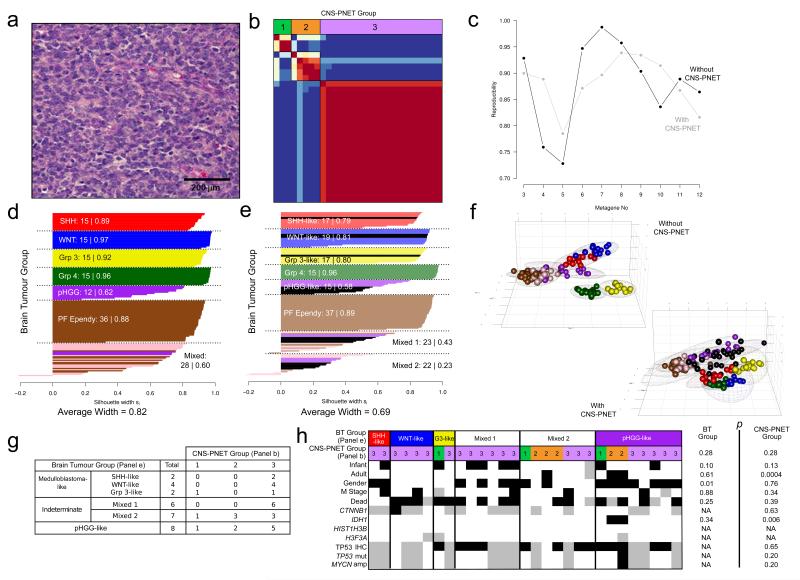

Figure 1. Consensus clustering of CNS-PNETs with other molecularly and histologically-defined paediatric brain tumours does not identify a discrete CNS-PNET tumour subgroup.

a. Representative photomicrograph of histologically homogeneous CNS-PNETs selected for analysis (H&E stain). A scale bar at 200μm shown. b. Consensus clustering of DNA methylation patterns in 29 CNS-PNETs: NMF using standard methods was carried out over 100 runs for 3 to 6 metagenes, with the peak cophenetic coefficient supporting three groups (metagenes). Consensus heatmap shows the consistency with which each sample was assigned to the 3 clusters (termed 1 to 3). c-h. Consensus clustering of CNS-PNETs with other molecularly and histologically-defined paediatric brain tumours. c. Plot shows average reproducibility with which each tumour was assigned to the same subgroup over 250 iterations. The highest reproducibility was observed at 7 metagenes (in mixed brain tumour cohort omitting CNS-PNETs) and 8 metagenes (in mixed brain tumour cohort including CNS-PNETs). d,e. Silhouette plots demonstrate that addition of CNS-PNETs reduces cluster quality and does not identify a discrete, CNS-PNET cluster. For each silhouette plot, the samples are coloured to show their originating tumour group. MBSHH, red; MBWNT, blue; MBGrp3, yellow; MBGrp4, dark green; pHGGs, purple; posterior fossa (PF) ependymomas, brown; supratentorial ependymomas, pink; CNS-PNETs, black. The number of tumours and silhouette width for each group are shown. d. Silhouette plot without CNS-PNETs. e. Silhouette plot with included CNS-PNETs. f. Principal component analysis (PCA) plots of clusters assigned by iterative, consensus NMF clustering, with covariance spheroids (95% confidence intervals) shown for each group. g. Relationships between assignment of CNS-PNET samples to clusters identified in analysis of CNS-PNETs-alone (b) or within analysis of multiple paediatric brain tumour groups (e). h. Clinico-pathological and molecular correlates of identified clusters. Infant (<3.0 years), adult (>16.0 years), male patients, M stage 2/3 tumours and patients dead of their disease are shown black. Patients with mutations in the brain-tumour associated genes CTNNB1, IDH1, HIST1H3B and H3F3A are shaded black. Finally, patients positive for TP53 IHC, TP53 mutation (mut) or MYCN amplification (amp) are shown (also black). For each track, missing data is shown grey. ‘p’ values are shown from chi-squared tests of incidence between groups.

We first undertook unsupervised clustering of the CNS-PNET tumour group based on their DNA methylation patterns using non-negative matrix factorisation (NMF [2, 14]). Three sub-groups produced the most consistent consensus clustering; the majority of tumours clustered confidently into a single large group (21/29), while the two smaller remaining groups (n≤5) were less well defined (Figure 1b).

Next, we sought to compare the DNA methylation patterns observed for CNS-PNETs with those of the seven other paediatric brain tumour groups with available data. Prior to the addition of CNS-PNETs into our analysis, these tumours formed seven groups as expected (Figure 1c,d,f), representing discrete confidently-defined (average silhouette width, 0.82) groups of MBWNT, MBSHH, MBGroup3 and MBGroup4, posterior-fossa ependymomas and pHGG tumours, and a mixed tumour group containing all (n=16) supratentorial ependymomas alongside some posterior fossa ependymomas (n=9) and pHGGs (n=3). Whilst the inclusion of CNS-PNETs in the analysis yielded 8 optimal clusters (Figure 1c,e,f), the overall quality of these clusters was reduced (average silhouette width, 0.69) and CNS-PNETs did not form a single discrete group; indeed, CNS-PNETs clustered into six of the different tumour groups observed (Figure 1e,f), showing closer similarities to the other clinically and molecularly-defined paediatric brain tumour groups investigated than to each other.

Finally, we made an initial assessment of relationships between the clustered CNS-PNETs and other clinical and molecular disease features (Figure 1g,h). Although numbers were limited, TP53 nuclear stabilisation was common and detected in most clusters, while TP53 mutation and MYCN amplification were rare. Most notably, both IDH1 mutations were exclusively detected in pHGG-like CNS-PNETs arising in adults [4], although no pHGG-characteristic HIST1H3B or H3F3A hotspot mutations were observed [15]. The single WNT pathway-activating CTNNB1 mutation was detected in a MBWNT-like CNS-PNET tumour. No relationships to clinical or pathological disease features were observed in this cohort (Figure 1h).

In summary, our data show that despite a defining histological homogeneity using current diagnostic criteria, CNS-PNETs display highly heterogeneous DNA methylation patterns which are more commonly related to other paediatric brain tumour types than to each other. These initial findings raise important issues in the classification of CNS-PNETs and indicate their current clinical definition and grouping by common ‘PNET’ histology [7], and treatment using uniform therapeutic approaches, does not adequately address their underlying biological and clinical complexity. Moreover, our data suggest the potential of refined molecular sub-classification for the improved diagnosis and discrimination of CNS-PNET molecular variants, and to support molecularly-directed clinical trials across tumour types defined currently by clinical and pathological criteria.

Despite the modest resolution of our platform, robust discrimination of recognised non-CNS-PNET tumour groups was achieved, both supporting these conclusions and highlighting the potential benefits of higher-resolution molecular investigations in expanded cohorts to validate and extend our findings. The variable DNA methylation patterns observed in CNS-PNETs are likely to represent complex factors, including cellular and developmental origins and ‘driver’ events in tumourigenesis [1]. The collection of snap-frozen tumour cohorts will now be essential to support comprehensive integrated genomic/epigenomic investigations, and comparison with transcriptomic features [11], which were not tractable in our current archival cohort. Finally, understanding the biological significance of epigenetic events in CNS-PNET and related tumour types could lead to the development of novel and/or targeted approaches for the improved therapy of these tumours.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from The Brain Tumour Charity, North of England Children’s Cancer Research (NECCR), CLIC-Sargent, The James Tudor and Joe Foote Foundations, The Gentleman’s Night Out and Cancer Research UK. Tumours investigated in this study include samples provided by the UK Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) as part of CCLG-approved biological study BS-2007-04. This study was conducted with ethics committee approval from Newcastle / North Tyneside REC (study reference 07/Q0905/71) and Trent REC (04/MRE04/72).

References

- 1.Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome - biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:726–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunet JP, Tamayo P, Golub TR, Mesirov JP. Metagenes and molecular pattern discovery using matrix factorization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4164–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308531101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haberler C, Laggner U, Slavc I, Czech T, Ambros IM, Ambros PF, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of INI1 protein in malignant pediatric CNS tumors: Lack of INI1 in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors and in a fraction of primitive neuroectodermal tumors without rhabdoid phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1462–8. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213329.71745.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden JT, Fruhwald MC, Hasselblatt M, Ellison DW, Bailey S, Clifford SC. Frequent IDH1 mutations in supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors (sPNET) of adults but not children. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1806–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korshunov A, Ryzhova M, Jones DT, Northcott PA, van Sluis P, Volckmann R, et al. LIN28A immunoreactivity is a potent diagnostic marker of embryonal tumor with multilayered rosettes (ETMR) Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:875–81. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, Lee KF, Lu Y, Clarke I, Shih D, Eberhart C, et al. Frequent amplification of a chr19q13.41 microRNA polycistron in aggressive primitive neuroectodermal brain tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:533–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller S, Rogers HA, Lyon P, Rand V, Adamowicz-Brice M, Clifford SC, et al. Genome-wide molecular characterization of central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumor and pineoblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:866–79. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfister S, Remke M, Castoldi M, Bai AH, Muckenthaler MU, Kulozik A, et al. Novel genomic amplification targeting the microRNA cluster at 19q13.42 in a pediatric embryonal tumor with abundant neuropil and true rosettes. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:457–64. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0467-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfister S, Remke M, Toedt G, Werft W, Benner A, Mendrzyk F, et al. Supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system frequently harbor deletions of the CDKN2A locus and other genomic aberrations distinct from medulloblastomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:839–51. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picard D, Miller S, Hawkins CE, Bouffet E, Rogers HA, Chan TS, et al. Markers of survival and metastatic potential in childhood CNS primitive neuro-ectodermal brain tumours: an integrative genomic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:838–48. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70257-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizer BL, Weston CL, Robinson KJ, Ellison DW, Ironside J, Saran F, et al. Analysis of patients with supratentorial primitive neuro-ectodermal tumours entered into the SIOP/UKCCSG PNET 3 study. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers HA, Kilday JP, Mayne C, Ward J, Adamowicz-Brice M, Schwalbe EC, et al. Supratentorial and spinal pediatric ependymomas display a hypermethylated phenotype which includes the loss of tumor suppressor genes involved in the control of cell growth and death. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:711–25. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0904-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwalbe EC, Williamson D, Lindsey JC, Hamilton D, Ryan SL, Megahed H, et al. DNA methylation profiling of medulloblastoma allows robust subclassification and improved outcome prediction using formalin-fixed biopsies. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:359–71. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]