Abstract

Histoplasma urine antigen (UAg) detection is an important biomarker for histoplasmosis. The clinical significance of low-positive (<0.6 ng/ml) UAg results was evaluated in 25 patients without evidence of prior Histoplasma infection. UAg results from 12/25 (48%) patients were considered falsely positive, suggesting that low-positive UAg values should be interpreted cautiously.

TEXT

Early recognition of Histoplasma capsulatum infection is essential for successful patient outcome, particularly among immunocompromised patients who are at increased risk for severe disease, including hematogenous dissemination. Available diagnostic modalities for histoplasmosis include fungal culture, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), histopathologic examination of tissue biopsy specimens, and Histoplasma antibody and antigen detection from body fluids. Among these methods, Histoplasma antigen detection from urine offers high clinical sensitivity for identification of patients with disseminated disease compared to alternative diagnostic methodologies (1–3). Additionally, Histoplasma antigen levels decline during disease resolution and are therefore monitored as a measure of patient response to therapy (4).

To date, the most utilized Histoplasma urine antigen (UAg) assay is the Histoplasma capsulatum Quantitative Antigen enzyme immunoassay (EIA) performed at MiraVista Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN) (2, 5). As of April 2012, the current quantifiable range of the MiraVista UAg EIA is 0.4 to 19 ng/ml, with samples falling within this range reported as “positive” (official notification from MiraVista Diagnostics). Values of <0.4 ng/ml or >19 ng/ml are considered positive and “below” or “above” the limit of quantification (LoQ), respectively. Finally, MiraVista also reports a result of “none detected” which is interpreted as “negative,” though a quantitative antigen value is not provided. The quantifiable range for this assay has undergone a number of iterations over the past decade. The most recent previous range was defined as 0.6 to 39 ng/ml, and, similarly to the current assay, values of <0.6 ng/ml were considered “positive, below the LoQ.”

(This study was presented in part at the 24th Annual European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in Barcelona, Spain, 10 to 13 May 2014.)

In a previous study conducted by our group, we compared a commercially available Histoplasma UAg EIA (Immuno Mycologics, Inc. [IMMY], Norton, OK) to the MiraVista assay and encountered multiple patients whose results were classified as “positive, below the LoQ” by the MiraVista EIA and yet were negative by the comparator assay (6). Interestingly, this subset of patients either never developed histoplasmosis or had been on antifungal therapy for 1 year or longer without active symptoms. Based on these observations, we questioned the clinical significance of low-positive MiraVista Histoplasma UAg results, defined as values of <0.6 ng/ml, specifically among patients without a history of histoplasmosis.

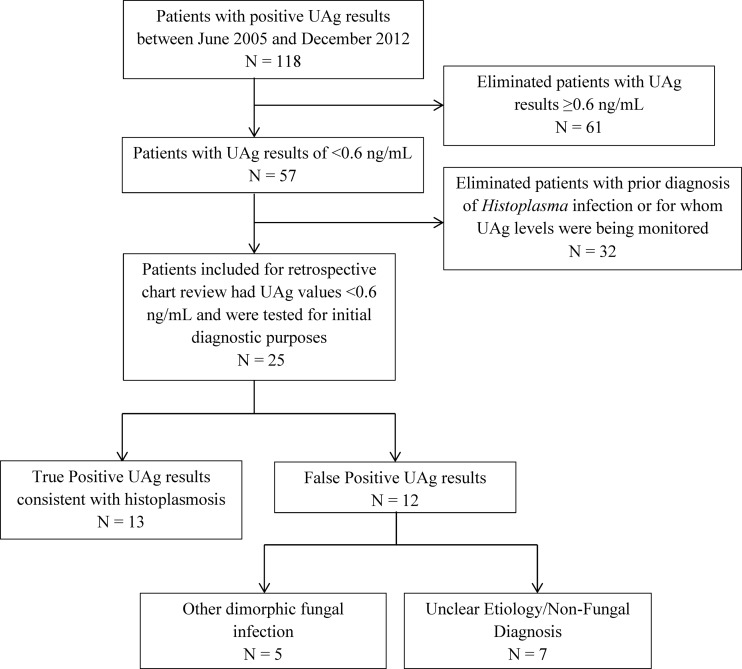

To address this issue, we identified all Mayo Clinic patients who tested positive by the MiraVista UAg EIA between June 2005 and December 2012 (n = 118; Fig. 1). From this subset, those with UAg results of ≥0.6 ng/ml (n = 61) and those with a prior diagnosis of histoplasmosis for whom UAg levels were being monitored (n = 32) were excluded from analysis. The medical charts for the remaining 25 patients were retrospectively reviewed to determine the clinical impact of a low-positive UAg result. Specifically, patient presentation at the time of testing, immune status, radiologic findings, exposure history, other microbiologic laboratory data, and any antifungal treatment were recorded. For this review, a confirmed case of histoplasmosis was defined by isolation of H. capsulatum in culture, a positive NAAT result (7), identification of fungal organisms consistent with H. capsulatum by histopathology, and/or strongly suggestive serologic evidence, defined as the presence of at least an H-band as demonstrated by immunodiffusion (ID) and complement fixation (CF) titers of ≥1:32 for the yeast and/or mycelial Histoplasma antigens. Patients who did not meet the above criteria and yet had positive Histoplasma serologies (e.g., M-band only by ID and CF titers between ≥1:8 and <1:32) and for whom an alternative diagnosis was not identified were classified as representing possible histoplasmosis cases. All other patients were classified as negative for histoplasmosis. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

FIG 1.

Selection for and evaluation of patients with low-positive (<0.6 ng/ml) Histoplasma UAg results by retrospective chart review.

Among the 25 patients with initial low-positive Histoplasma UAg values, 12 were considered to have a confirmed case of histoplasmosis on the basis of identification by recovery of the organism in culture (n = 4) from various sources (i.e., tissue, bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL] fluid, or bone marrow), by positive histopathology (n = 1, lung biopsy specimen), by a positive NAAT result (n = 1, bone marrow), or by the patient's serologic profile (n = 6). An additional patient was considered to have possible pulmonary histoplasmosis as determined on the basis of the presence of an M-band by ID and a yeast CF titer of 1:16; due to the lack of an alternative diagnosis, this patient was treated with itraconazole. Collectively, the low-positive Histoplasma UAg values for these 13/25 (52%) patients were considered true-positive results and led to the prompt diagnosis of H. capsulatum infection and initiation of antifungal therapy.

Among the remaining 12 (48%) patients, the low-positive UAg values were considered falsely positive, as the patients were ultimately diagnosed with an alternative disease (n = 9) or never progressed to histoplasmosis (n = 3) (Table 1). Of these 12 patients, 3 were diagnosed with disseminated or pulmonary blastomycosis based on recovery of Blastomyces dermatitidis from BAL fluid or a strongly positive B. dermatitidis UAg test result (MiraVista Diagnostics). Coccidioidis immitis-Coccidioidis posadasii infections were identified in an additional two patients based on identification of a spherule from a lymph node biopsy specimen and a suggestive serologic profile. Cross-reactivity of the Histoplasma UAg assay with these dimorphic fungi and other fungal agents, including Penicillium, Paracoccidioides, and, rarely, Aspergillus species, has been described previously and remains a noted limitation of the MiraVista assay (5). However, despite the lack of analytical specificity among these five low-positive Histoplasma UAg results, they remain of clinical value in this patient group as the treatments of Histoplasma and Blastomyces infections are similar and the risk for Coccidioides infection can be determined based on prior travel history (e.g., travel to the southwest United States). The consideration of the possibility on an alternative fungal infection in at-risk patients with low-positive Histoplasma UAg values is recommended, and further testing by alternative methods (e.g., serology, culture) would be beneficial in such cases.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and laboratory findings for patients with falsely positive Histoplasma UAg values of <0.6 ng/mla

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/sex | Presenting symptom(s) | Comorbidity(ies)/immune status | Radiologic findings at presentation | Other microbiology findings | Final diagnosis | Antifungals started? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46/F | Fever; new DVT/PICC | Sacral OM 3 months prior | N/A | Enterobacter cloacae BSI | E. cloacae BSI | No |

| 2 | 67/M | Weight loss, dysphagia | Coronary/peripheral artery disease | Hepatosplenomegaly | H. capsulatum yeast CF (1:16) | Sarcoidosis | No |

| 3 | 73/M | Incidental cavitary lesion | B-cell lymphoma on chemotherapy | Left lung cavitary lesion | N/A | Unclear etiology | Empirical fluconazole |

| 4 | 27/F | Fever, cough | None | Bilateral lung infiltrates | N/A | Community-acquired pneumonia | No |

| 5 | 70/F | Respiratory failure | Lung carcinoma on chemotherapy | Bilateral lung infiltrates | Blastomyces UAg positive (2.19 ng/ml) | Disseminated blastomycosis | Itraconazole |

| 6 | 81/M | Pancytopenia, noncaseating granuloma in BM | Coronary artery disease | Splenomegaly | H. capsulatum yeast CF (1:16); H. capsulatum ID; M band Coccidioides CF (1:2) | Granulomatous disease, secondary to sarcoidosis | No |

| 7 | 74/F | Persistent pulmonary infiltrates | Hypertension | Bilateral lung infiltrates | Coccidioides IgG ID positive and CF (1:8) | Coccidioidomycosis | Fluconazole |

| 8 | 74/M | Elevated ESR | RA on methotrexate | Nodular lung infiltrates | Blastomyces recovered from BAL fluid | Pulmonary blastomycosis | Itraconazole |

| 9 | 37/M | Lymphadenopathy | Unclear | N/A | Coccidioides spherule identified from lymph node biopsy specimen | Coccidioides lymphadenopathy | Fluconazole |

| 10 | 55/M | Fever, fatigue | Stem cell transplant on prednisone | Bilateral ground-glass infiltrates | Pseudomonas isolated from sputum | Unclear etiology, initiated on ciprofloxacin | No |

| 11 | 66/F | Incidental CT finding | Remote esophageal cancer | Upper lobe nodules | N/A | Unclear etiology | No |

| 12 | 11/F | Fever, dry cough | None | Cavitary infiltrate | Blastomyces EIA and UAg positive | Pulmonary blastomycosis | Itraconazole |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; BM, bone marrow; DVT/PICC, deep vein thrombosis/peripherally inserted central catheter; ID, immunodiffusion; CF, complement fixation; OM, osteomyelitis; BSI, bloodstream infection; WL, weight loss; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HA, headache; CT, computed tomography; N/A, not applicable.

The remaining 7/12 patients either received an alternative diagnosis (n = 4) or remained without a defined etiology for their symptoms (n = 3). Notably, one patient was started on empirical fluconazole treatment despite the absence of additional supportive data for a fungal infection, and though two patients had positive Histoplasma serologic findings, both were ultimately diagnosed with sarcoidosis and antifungal treatment was withheld. Importantly, neither of these patients developed histoplasmosis or infection with an alternative agent known to cross-react with the UAg assay in the year following the initial low-positive Histoplasma UAg result.

The major limitation of this retrospective study was the small number of patients with low-positive Histoplasma UAg levels (n = 25). However, this remains the first review of the clinical utility of low-positive UAg values and adds previously undocumented data to the ever-growing understanding of this assay.

In conclusion, our evaluation suggests that while the Histoplasma UAg assay remains an invaluable tool for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, low-positive Histoplasma UAg results should be interpreted cautiously and correlated with additional laboratory findings (e.g., serology, culture, repeat Histoplasma UAg testing) to confirm the diagnosis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Wheat LJ. 2006. Antigen detection, serology, and molecular diagnosis of invasive mycoses in the immunocompromised host. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 8:128–139. 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE, Kauffman CA. 2007. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:807–825. 10.1086/521259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guimarães AJ, Nosanchuk JD, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. 2006. Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis. Braz. J. Microbiol. 37:1–13. 10.1590/S1517-83822006000100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hage CA, Kirsch EJ, Stump TE, Kauffman CA, Goldman M, Connolly P, Johnson PC, Wheat LJ, Baddley JW. 2011. Histoplasma antigen clearance during treatment of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS determined by a quantitative antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18:661–666. 10.1128/CVI.00389-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, Baddour LM, Assi M, McKinsey DS, Hammoud K, Alapat D, Babady NE, Parker M, Fuller D, Noor A, Davis TE, Rodgers M, Connolly PA, El Haddad B, Wheat LJ. 2011. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53:448–454. 10.1093/cid/cir435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theel ES, Jespersen DJ, Harring J, Mandrekar J, Binnicker MJ. 2013. Evaluation of an enzyme immunoassay for detection of Histoplasma capsulatum antigen from urine specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:3555–3559. 10.1128/JCM.01868-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babady NE, Buckwalter SP, Hall L, Le Febre KM, Binnicker MJ, Wengenack NL. 2011. Detection of Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum from culture isolates and clinical specimens by use of real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:3204–3208. 10.1128/JCM.00673-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]