Abstract

The presence of HIV-1 non-B subtypes in Western Europe is commonly attributed to migration of individuals from non-European countries, but the possible role of domestic infections with non-B subtypes is not well investigated. The French mandatory anonymous reporting system for HIV is linked to a virological surveillance using assays for recent infection (<6 months) and serotyping. During the first semester of years 2007 to 2010, any sample corresponding to a non-B recent infection was analyzed by sequencing a 415-bp env region, followed by phylogenetic analysis and search for transmission clusters. Two hundred thirty-three recent HIV-1 infections with non-B variants were identified. They involved 5 subtypes and 7 circulating recombinant forms (CRFs). Ninety-two cases (39.5%) were due to heterosexual transmissions, of which 39 occurred in patients born in France. Eighty-five cases (36.5%) were identified in men having sex with men (MSM). Forty-three recent non-B infections (18.5%) segregated into 14 clusters, MSM being involved in 11 of them. Clustered transmission events included 2 to 7 cases per cluster. The largest cluster involved MSM infected by a CRF02_AG variant. In conclusion, we found that the spread of non-B subtypes in France occurs in individuals of French origin and that MSM are particularly involved in this dynamic.

INTRODUCTION

Since its introduction in the human species, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M has diversified into 9 genetic subtypes (A, B, C, D, F, G, H, J, and K) and numerous circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) that arise from recombination between one or several parental viruses in coinfected or superinfected individuals (1). Depending on its epidemiological success, each clade has a specific distribution. Subtype B predominates in the Americas, Europe, Japan, and Australia, whereas non-B subtypes predominate in Africa and in most Asian countries. Many studies have reported an increasing prevalence of non-B subtypes in Europe since the beginning of the epidemic (2–10). Whereas there is a common notion that HIV-1 infections with non-B subtypes are mainly associated with migrant populations from the developing world, there is increasing evidence that the epidemiology of non-B viruses in Europe results from both migration and domestic transmissions (11–13). Most of the studies have described the increasing prevalence of non-B variants in Europe among newly diagnosed HIV-1 infections or patients referred for antiretroviral resistance testing (4, 6–9). However, the duration of infection for each new diagnosis was frequently unknown in these studies. Therefore, the dynamic of the non-B subepidemics cannot be described accurately since it necessitates focusing on patients with known dates of infection, particularly those who have been infected recently. This includes patients diagnosed at the time of primary infection (10, 14, 15). Alternatively, serologic assays for recent infection (RI assays) that have been developed and validated during the last decade allow the identification of patients who have been infected for less than a few months, approximately 6 months in most of the assays (16–19).

In the present work, we took advantage of the virological surveillance that is linked to the mandatory notification of new HIV diagnoses that was implemented in France in 2003 and includes the determination of recent infection and serotyping for any case (20, 21). We conducted a nested study whose aim was to identify the sociodemographic characteristics of patients recently infected by non-B variants during the 2007-2010 period. In order to answer this question, we sequenced and characterized the viruses present in samples collected from patients identified as recently infected (less than 6 months) according to the RI assay, and a molecular phylogeny approach was applied to identify transmission clustering. The data show, at a nationwide level, that most of the ongoing non-B transmissions occur in individuals of French origin and that men having sex with men (MSM) are particularly involved in this dynamic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants.

The mandatory anonymous HIV case reporting was implemented in France in 2003 (20, 21). The notification form includes demographic data (sex, age, country of birth, current nationality, and region of residency), mode of transmission, clinical stage at HIV diagnosis, and reasons for HIV screening (20). It is linked to a virological surveillance program that was approved by the French National Ethics Committee (CNE) and the French computer database watchdog commission (CNIL). When an HIV infection is newly diagnosed, the laboratory is asked to send dried serum spots (DSS) from the stored serum sample to the HIV French National Reference Center (NRC). The NRC uses the serum eluted from DSS to determine whether the HIV infection is recent (less than 180 days) or not and to characterize the type, group, and subtype of HIV. The enzyme immunoassay run to identify recent infection (EIA-RI) is based on an algorithm that combines standardized measures of antibody binding to the immunodominant epitope of gp41 and the V3 region of gp120 (22). Assessment of its performance in the framework of the French national HIV case surveillance revealed that the sensitivity and specificity were 88% and 84%, respectively (23). Type, group, and subtype of HIV are determined using a single enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (SSEIA), shown previously as presenting good predictive values to distinguish subtype B infections from non-B infections (24, 25). However, a significant part of infections cannot be serotyped (not typeable [NT]), mainly within the first months postinfection due to a low titer of antibodies to the V3 region.

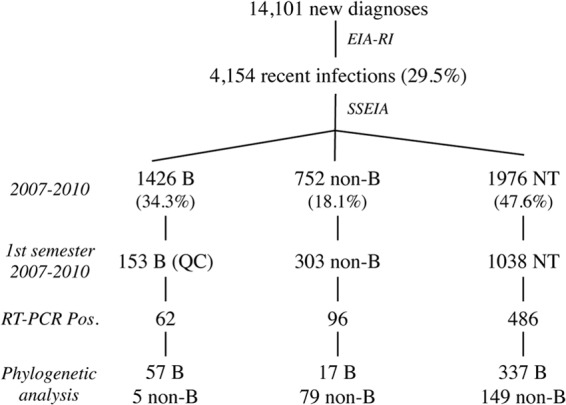

In the present study, we selected all HIV-1 recent infections identified by EIA-RI during the first semester of each year, from 2007 to 2010 (Fig. 1). Among them, all samples that were identified as non-B or NT by SSEIA were included for molecular analysis. In addition, at least 1 sample that was identified as subtype B by SSEIA for 10 non-B or NT samples (i.e., the first B sample after 10 successive non-B or NT samples) was also included for molecular analysis, as a quality control (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Study population and results of the phylogenetic analysis. NT, not typeable; QC, quality control.

HIV-1 genotyping.

The genotyping analyses were conducted on a 415-bp fragment of the envelope glycoprotein gp41 coding sequence amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) from RNA extracted from DSS, as described previously (13, 20). Nucleotide sequences were aligned with 70 reference sequences representative of HIV-1 group M subtypes and the most common circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) available in the HIV Los Alamos database (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov), using Clustal W with minor manual adjustments (26). The reference sequences were selected based on the fact that they were issued from complete genomes. There were 2 to 5 sequences for each pure subtype (A to K) and 1 to 5 sequences for each of 14 CRFs. Subtype or CRF assignments were achieved by constructing phylogenetic trees using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (27). Distances were calculated using MEGA 5 based on the nonevolutive Kimura two-parameter model (http://www.megasoftware.net) (28, 29). The reliability of the branching orders was assessed by bootstrap analysis of 500 replicates. The subtype or CRF phylogenetically assigned to each sequence was systematically checked by comparison with the best-matched HIV-1 sequences retrieved in BLAST searches (HIV Los Alamos Database).

Transmission clusters.

For the identification of potential transmission clusters, gp41 sequences were grouped according to their HIV-1 subtype/CRF assignment and multiple sequence alignments, including unrelated reference sequences from the Los Alamos HIV database, were created using Clustal W (26). Sequence interrelationships were first deduced by the NJ method as described below. In order to use stringent criteria, only clusters with a bootstrap value higher than 90 and an average genetic distance of <0.015 were selected (30). Clusters including sequences amplified in the same run were excluded from the study to avoid any possibility of contamination. The robustness of the transmission clusters was further tested using the maximum likelihood (ML) method based on the evolutive general time reversible (GTR) model from 1,000 bootstrap replicates, using gamma distributions of 5 discrete gamma categories, all sites of the data set, all the codon positions, and nearest-neighbor interchange (NNI) as the ML heuristic method in MEGA 5 (29). All the clusters selected from the NJ phylogenetic analysis were confirmed by the ML method on the basis of bootstrap values higher than 90%. Infections in clusters were finally validated for congruent polymorphisms and mutational motifs.

RESULTS

Non-B infections among HIV-1 recent infections.

Between January 2007 and December 2010, 14,101 new HIV diagnoses were reported for which a DSS was sent to the NRC (Fig. 1). The EIA-RI allowed the detection of 4,154 HIV-1 recent infections (29.5% of all new HIV diagnoses) for the whole year (31), including a large majority of men (77.6%; n = 3,223) (Table 1). Data on mode of transmission were available for 71.5% (n = 2,969) of the patients with recent infection. Men having sex with men (MSM) were the predominant transmission category (60.5%; n = 1,795) followed by heterosexual contact (38.3%; n = 1,138). Countries of birth were known for 69.0% (n = 2,866) of the patients. A large majority of these patients were born in France (74.3%; n = 2,129). Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) was the second most common geographic origin identified (13.3%; n = 380).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with genotype-confirmed B or non-B HIV-1 recent infections

| Characteristic | No. of cases with HIV-1 subtype |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Non-B |

|||||||||||

| A | C | D | F | G | 02_AG | 01_AE | 06_cpx | 42_BF | Others and Ua | Total (%) | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 382 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 108 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 170 (73.0) |

| Female | 29 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 31 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 63 (27.0) | ||

| Total | 411 | 25 | 19 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 139 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 233 |

| Transmission categoryb | ||||||||||||

| MSM | 259 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 56 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 85 (46.7) | |

| France | 211 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 46 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 70 (88.6) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 | 1 | 1 (1.3) | |||||||||

| Other | 20 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 (10.1) | ||||||

| Unknown | 27 | 5 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| Heterosexual male | 46 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 26 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 45 (24.7) | ||

| France | 35 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 19 (50.0) | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 17 (44.7) | |||||

| Other | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 (5.3) | ||||||||

| Unknown | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | |||||||

| Heterosexual female | 20 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 26 | 1 | 2 | 47 (25.8) | ||||

| France | 13 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 20 (44.4) | |||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 22 (48.9) | |||||

| Other | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 (6.7) | ||||||||

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| IVDUe | 1 | 2 | 2 (1.1) | |||||||||

| Other | 1 | 2 | 3 (1.7) | |||||||||

| Unknown | 85 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 28 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 51 |

| Country of birthc | ||||||||||||

| France | 273 | 9 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 73 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 120 (67.8) |

| Other European country | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 (3.9) | |||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 6 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 26 | 3 | 43 (24.3) | |||||

| North Africa | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 (2.3) | ||||||||

| America | 5 | 2 | 2 (1.1) | |||||||||

| Asia | 8 | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |||||||||

| Unknown | 104 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 34 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 56 |

| Region of residenced | ||||||||||||

| Paris and surrounding area | 144 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 71 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 108 (50.7) |

| Other | 230 | 13 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 54 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 105 (49.3) |

| Unknown | 37 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 20 | |||||

Others: 1 CRF03_AB, 1 CRF09_cpx, 1 CRF12_BF; U, 2 unidentified forms.

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the patients for whom data on transmission were available.

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the patients for whom countries of birth were known.

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the patients for whom regions of residence were known.

IVDU, intravenous drug user.

Among the 4,154 recent infections, serotyping allowed identification of 1,426 subtype B infections (34.3%) and 752 non-B infections (18.1%). Close to 50% of the samples (n = 1,976, 47.6%) from patients with recent infection were not typeable by SSEIA due to insufficient reactivity to V3 antigens. All the non-B (n = 303) or NT (n = 1,038) samples collected during each first semester of the 4-year period were submitted to molecular analysis. As a quality control, 153 B samples were also included in the molecular study (Fig. 1). Amplified DNA products were obtained for 43.1% of DSS included (644 of 1,494). The low success rate of the RT-PCR assay was similar to our previous experiences (13, 20, 32). Indeed, we previously showed that the RT-PCR assay applied to our DSS procedure usually necessitates a viral load of over 10,000 copies/ml to yield a positive result (32, 33). In addition, we cannot exclude that other factors such as deterioration of viral RNA due to storage and transportation before treatment of the DSS contributed to the low amplification percentage. After sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, 149 of 486 NT samples corresponded to non-B infections. Seventy-nine of 96 non-B samples (82.3%) identified by serotyping were confirmed as non-B by genotyping. Similarly, 57 of 62 B samples (91.9%) identified by serotyping were confirmed as B by genotyping. Therefore, combining these data, the specificity of the serotyping assay was 0.86. Overall, we identified 233 recent infections by non-B variants (Fig. 1). A wide diversity of non-B clades was observed among these non-B recent infections (Table 1). There were 5 pure subtypes (A, C, D, F, and G) and 7 CRFs (01_AE, 02_AG, 03_AB, 06_cpx, 09_cpx, 12_BF, and 42_BF). Among them, CRF02_AG was the most prevalent clade, representing 59.7% (139/233) of the cases, followed by clades A (10.7%, n = 25), C (8.2%, n = 19), CRF01_AE (4.7%, n = 11), and CRF06_cpx (4.3%, n = 10) (Table 1). Two sequences not clustering with any known subtype or CRF were defined as unidentified forms (U).

Epidemiological characteristics of recent infections with non-B variants.

Ninety-two cases were due to heterosexual transmissions, of which 39 occurred in patients originating from SSA but 39 occurred among individuals born in France (Table 1). These data confirm the continuous spread of non-B variants through heterosexual contacts in the French population but also the idea that African residents might have acquired their infection once in French territory. Eighty-five cases were identified in MSM, of whom 70 were born in France. Only one of the 85 MSM studied was born in SSA. Overall, 120 recent infections with non-B variants occurred in individuals born in France whereas only 43 were identified in patients born in SSA, underlining the established spread of non-B viruses in the French population. All 12 non-B clades that were involved in recent infections, except one (clade G), were found in the MSM population. The risk transmission group was known for 111 cases among 139 recent infections with the most prevalent non-B clade, CRF02_AG. Fifty percent (n = 56, 50.5%) of them occurred in MSM. All the patients with a known transmission risk factor infected with a subtype D variant (6 of 6) and most of those infected with a CRF01_AE virus (7 of 10) were also MSM. Approximately half of the non-B recent infections occurred in the Paris area (108 in the Paris area versus 105 in other regions of France).

Transmission clusters.

The molecular analysis revealed that 106 of the 644 recent infections for which nucleotide sequences were available (16.5%) segregated into 41 different transmission clusters (Fig. 2). Fourteen clusters involving 43 of 233 non-B recent infections (18.5%) were identified. There were 7 CRF02_AG clusters, 2 A1 clusters, 2 CRF06_cpx clusters, and one cluster of each of the following clades: C, D, and CRF42_cpx (Fig. 2). MSM were involved in 11 of them (6 CRF02_AG, 2 A1, 1 D, 1 CRF06_cpx, and 1 CRF42_BF), a frequency similar to that observed in clusters of B transmissions (MSM were involved in 23 of 27 subtype B clusters). Eight of 14 non-B clusters contained at least 3 patients, the largest cluster of 7 cases involving MSM infected with a CRF02_AG variant. Although this study was not designed to be comparative, it is interesting that most of the non-B clusters were of larger size than the B clusters: 8 of 14 (57.1%) non-B clusters contained more than two cases versus only 3 of 27 B clusters (11.1%) (Fig. 2). In the majority of the cases (9/14; 64.3%), the non-B clusters involved patients living in different geographical regions, including systematically at least one patient from the Paris area in these cases (Fig. 2). The trend was the opposite for B clusters, only 11 of 27 B clusters (40.7%) concerning patients from different regions.

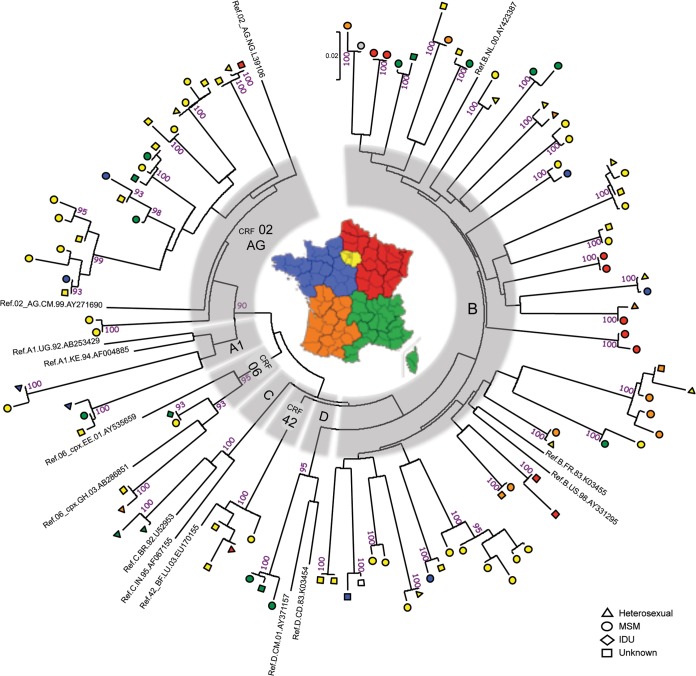

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 106 gp41 sequences from HIV-1 variants involved in transmission clusters. Multiple-sequence alignment including reference sequences (1 to 3 sequences representative of each subtype or CRF for which a cluster was identified) was conducted using Clustal W (26). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. Genetic distances were computed using the Kimura two-parameter method in MEGA5 (28, 29). The optimal tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the distances. The reliability of the branching orders was assessed by bootstrap analysis of 500 replicates. Viruses isolated in heterosexual patients, MSM, injecting drug users (IDU), and individuals with unknown risk factors are indicated by triangles, circles, diamonds, and squares, respectively. The region of residence is shown for each case. The color code corresponds to five regions of metropolitan France: Paris area (yellow), northeast (red), southeast (green), southwest (orange) and northwest (dark blue). One case was a patient living in the French West Indies (in gray), and the region of residence was not known for one case (empty symbol).

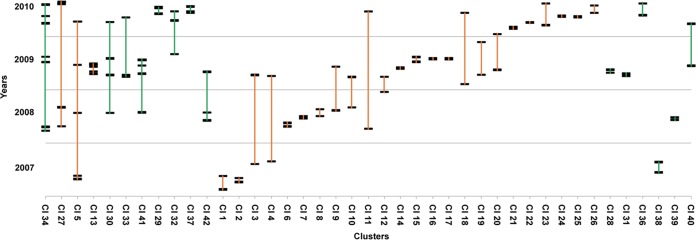

We analyzed the time interval between the date of diagnosis of the first and the last infection within each cluster. Although variable, we found that the time interval was less than 6 months for the majority of the cases (Fig. 3). The time interval was less than 6 months for 7 of 14 non-B clusters and 17 of 27 clusters involving B variants. It has been suggested that recent HIV-1 infections, particularly primary infections, contribute significantly to the spread of HIV-1 (14, 15). Although these data are not a proof of higher rapidity of transmission of the variants involved in the clusters, this observation at least suggests a rapid spread of these variants, regardless of the subtype.

FIG 3.

Time interval between HIV-1 infections within each cluster. Large clusters are shown on the left part of the scheme. Each cluster is represented by a vertical bar (B, orange; non-B, green). Each infection is represented by a large horizontal bar.

DISCUSSION

Many studies have demonstrated an increasing prevalence of HIV-1 non-B subtypes in Europe during the last decade. However, except for a few studies (10, 15, 34), most of them were conducted among patients whose date of infection was not known, and the studies were not conducted at a nationwide level. Taking advantage of the virological surveillance that is linked to the mandatory notification of new HIV diagnoses that includes the identification of patients with recent infection (less than 6 months), we conducted the present study in order to provide a better description of the epidemiological characteristics of the non-B subepidemics at a national level. The recentness of infection was identified in each sample using the EIA-RI (IDE/V3) assay (20, 24). Recent studies have shown that a combination of assays may improve the accuracy of the data (35–38). Although we did not use a multiassay algorithm, our strategy which corrects the false recentness for any patient known to be at the AIDS stage, a major factor for misclassification, was shown to be relevant at a population level (20, 23, 24). In order to focus on recently transmitted non-B variants, the serotyping screening allowed us to discard the B recent infections from a more time-consuming molecular analysis. The strategy was validated by the quality control that was performed all throughout the study and showed a specificity of the serotyping assay of around 92% for subtype B samples. Therefore, most of the technical efforts were concentrated on samples from recent infections that were predicted as due to non-B variants by serotyping or were not serotypeable. To our knowledge, this is the first study that provides a descriptive analysis of patients recently infected with HIV-1 non-B subtypes at a nationwide level in a western country.

Two hundred thirty-three non-B recent infections were identified during a period covering each first semester of the years 2007 to 2010. They involved 5 non-B subtypes and 7 CRFs, showing the ongoing spread of highly diverse variants that were not initially present at the time of emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in France. As already observed (6, 10), CRF02_AG was the most prevalent clade, representing close to 60% of non-B recent infections. This is due to the historical links between France and West African countries, where the CRF02_AG clade is predominant. Surprisingly, the majority of non-B recent infections were observed not in individuals originating from sub-Saharan Africa but in French natives. Almost half of the non-B recent infections were identified in MSM, 11 among the 12 non-B clades observed in the present study being detected in the MSM population. Altogether, these data show the spread of non-B subtypes in individuals of French origin and show that MSM are particularly involved in this dynamic. This epidemiological evolution was illustrated recently through the description of the new CRF56_cpx and several distinct B-CRF02 unique recombinant forms (URFs) circulating in this high-risk group (39, 40). However, the precise incidences of HIV-1 non-B infections in different risk groups cannot be compared since the frequency of HIV testing is highly variable in these populations. Indeed, these data were obtained from a sample which selects people diagnosed soon after their infection, and MSM are more likely to be diagnosed early in infection than are African migrant populations, due to more frequent use of HIV testing (21).

Close to 20% of non-B recent infections segregated into 14 clusters, MSM being involved in 11 of them. Clusters included 2 to 7 cases per cluster and were dispersed in all regions of the country. The largest cluster involved MSM infected by a CRF02_AG variant. The time interval between the first and the last infection within each cluster was less than 6 months for half of the clusters. Therefore, the data are suggestive of multiple introductions of non-B variants with a high rate of transmission, particularly in the MSM population. However, the comparison between B and non-B clusters could not be performed with accuracy in the present study since a significant proportion of B recent infections identified through the serotyping assay were not included in the molecular study. Another limitation of this study concerned the limited size of the amplified sequence that corresponds to a single region of the env gene. The clade was therefore attributed based on the phylogenetic analysis of this short region, and we cannot exclude that some patients were infected by mosaic viruses which, consequently, were not identified.

The spread of HIV-1 non-B subtypes has been described in France through the surveillance of transmitted drug resistance mutations in patients with primary infection enrolled in the French ANRS PRIMO cohort. Most of the enrolled cases were identified in large hospital centers (10, 15). Complementary to this surveillance, our study which is linked to the mandatory anonymous HIV case reporting provides data from samples collected from any laboratory in the country and relies on the biological identification of any recent infection, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, leading probably to more exhaustive data. Although one of the limitations of our study is the relatively low success of sequence amplification, the virological surveillance based on a very simple collection of dried serum spots which is linked to the mandatory notification of new HIV diagnoses has been shown to be feasible at a national level. It provides important demographic and epidemiological data on the recently infected population that were not described with such accuracy in previous reports. The present substudy clearly indicates that the spread of non-B subtypes in France occurs in individuals of French origin and that MSM are particularly involved in this dynamic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the Institut de Veille Sanitaire, funded by the French Ministry of Health. The assay for recent infection was developed with support from the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida et les Hépatites (ANRS, Paris, France).

We thank all participants in the national surveillance program, particularly the biologists, physicians, and public health doctors. The excellent technical assistance of Anne-Sophie Daubier, Agnès Jousset, Julien Marlet, Karl Stefic, and Marie Leoz was appreciated.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 September 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Hemelaar J, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Osmanov S, WHO-UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterisation 2011. Global trends in molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 during 2000–2007. AIDS 25:679–689. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328342ff93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barin F, Courouce AM, Pillonel J, Buzelay L. 1997. Increasing diversity of HIV-1M serotypes in French blood donors over a 10-year period (1985-1995). Retrovirus Study Group of the French Society of Blood Transfusion. AIDS 11:1503–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sönnerborg A, Durdevic S, Giesecke J, Sällberg M. 1997. Dynamics of the HIV-1 subtype distribution in the Swedish HIV-1 epidemic during the period 1980 to 1993. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 13:343–345. 10.1089/aid.1997.13.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Böni J, Pyra H, Gebhardt M, Perrin L, Bürgisser P, Matter L, Fierz W, Erb P, Piffaretti JC, Minder E, Grob P, Burckhardt JJ, Zwahlen M, Schüpbach J. 1999. High frequency of non-B subtypes in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infections in Switzerland. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 22:174–179. 10.1097/00126334-199910010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snoeck J, Van Laethem K, Hermans P, Van Wijngaerden E, Derdelinckx I, Schrooten Y, van de Vijver DA, De Wit S, Clumeck N, Vandamme A-M. 2004. Rising prevalence of HIV-1 non-B subtypes in Belgium: 1983–2001. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 35:279–285. 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Descamps D, Chaix M-L, Montes B, Pakianather S, Charpentier C, Storto A, Barin F, Dos Santos G, Krivine A, Delaugerre C, Izopet J, Marcelin A-G, Maillard A, Morand-Joubert L, Pallier C, Plantier J-C, Tamalet C, Cottalorda J, Desbois D, Calvez V, Brun-Vézinet F, Masquelier B, Costagliola D, ANRS AC11 Resistance Study Group 2010. Increasing prevalence of transmitted drug resistance mutations and non-B subtype circulation in antiretroviral-naive chronically HIV-infected patients from 2001 to 2006/2007 in France. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2620–2627. 10.1093/jac/dkq380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox J, Castro H, Kaye S, McClure M, Weber JN, Fidler S, UK Collaborative Group on HIV Drug Resistance 2010. Epidemiology of non-B clade forms of HIV-1 in men who have sex with men in the UK. AIDS 24:2397–2401. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833cbb5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Alba JM, Holguín A, Garcia R, García-Bujalance S, Alonso R, Suárez A, Delgado R, Cardeñoso L, González R, García-Bermejo I, Portero F, de Mendoza C, González-Candelas F, Galán J-C. 2011. Molecular surveillance of HIV-1 in Madrid, Spain: a phylogeographic analysis. J. Virol. 85:10755–10763. 10.1128/JVI.00454-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abecasis AB, Wensing AM, Paraskevis D, Vercauteren J, Theys K, Van de Vijver DA, Albert J, Asjö B, Balotta C, Beshkov D, Camacho RJ, Clotet B, De Gascun C, Griskevicius A, Grossman Z, Hamouda O, Horban A, Kolupajeva T, Korn K, Kostrikis LG, Kücherer C, Liitsola K, Linka M, Nielsen C, Otelea D, Paredes R, Poljak M, Puchhammer-Stöckl E, Schmit JC, Sönnerborg A, Stanekova D, Stanojevic M, Struck D, Boucher CA, Vandamme A-M. 2013. HIV-1 subtype distribution and its demographic determinants in newly diagnosed patients in Europe suggest highly compartmentalized epidemics. Retrovirology 10:7. 10.1186/1742-4690-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaix M-L, Seng R, Frange P, Tran L, Avettand-Fenoël V, Ghosn J, Reynes J, Yazdanpanah Y, Raffi F, Goujard C, Rouzioux C, Meyer L, Cohort Study Group ANRS PRIMO 2013. Increasing HIV-1 non-B subtype primary infections in patients in France and effect of HIV subtypes on virological and immunological responses to combined antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56:880–887. 10.1093/cid/cis999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns FM, Arthur G, Johnson AM, Nazroo J, Fenton KA, SONHIA Collaboration Group 2009. United Kingdom acquisition of HIV infection in African residents in London: more than previously thought. AIDS 23:262–266. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c546b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Wyl V, Kouyos RD, Yerly S, Böni J, Shah C, Bürgisser P, Klimkait T, Weber R, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, Staehelin C, Battegay M, Vernazza PL, Bernasconi E, Ledergerber B, Bonhoeffer S, Günthard HF, Swiss HIV Cohort Study 2011. The role of migration and domestic transmission in the spread of HIV-1 non-B subtypes in Switzerland. J. Infect. Dis. 204:1095–1103. 10.1093/infdis/jir491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brand D, Cazein F, Lot F, Brunet S, Thierry D, Moreau A, Pillonel J, Semaille C, Barin F. 2012. Continuous spread of HIV-1 subtypes D and CRF01_AE in France from 2003 to 2009. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2484–2488. 10.1128/JCM.00319-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner BG, Roger M, Stephens D, Moisi D, Hardy I, Weinberg J, Turgel R, Charest H, Koopman J, Wainberg MA, Montreal Cohort Study Group PHI 2011. Transmission clustering drives the onward spread of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in Quebec. J. Infect. Dis. 204:1115–1119. 10.1093/infdis/jir468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frange P, Meyer L, Deveau C, Tran L, Goujard C, Ghosn J, Girard P-M, Morlat P, Rouzioux C, Chaix M-L, French ANRS CO6 Cohort Study Group PRIMO 2012. Recent HIV-1 infection contributes to the viral diffusion over the French territory with a recent increasing frequency. PLoS One 7:e31695. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen RS, Satten GA, Stramer SL, Rawal BD, O'Brien TR, Weiblen BJ, Hecht FM, Jack N, Cleghorn FR, Kahn JO, Chesney MA, Busch MP. 1998. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. JAMA 280:42–48. 10.1001/jama.280.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy G, Parry JV. 2008. Assays for the detection of recent infections with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Euro Surveill. 13:4–10 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=18966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guy R, Gold J, Calleja JM, Kim AA, Parekh B, Busch M, Rehle T, Hargrove J, Remis RS, Kaldor JM, WHO Working Group on HIV Incidence Assays 2009. Accuracy of serological assays for detection of recent infection with HIV and estimation of population incidence: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:747–759. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busch MP, Pilcher CD, Mastro TD, Kaldor J, Vercauteren G, Rodriguez W, Rousseau C, Rehle TM, Welte A, Averill MD, Garcia Calleja JM, WHO Working Group on HIV Incidence Assays 2010. Beyond detuning: 10 years of progress and new challenges in the development and application of assays for HIV incidence estimation. AIDS 24:2763–2771. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semaille C, Barin F, Cazein F, Pillonel J, Lot F, Brand D, Plantier J-C, Bernillon P, Le Vu S, Pinget R, Desenclos J-C. 2007. Monitoring the dynamics of the HIV epidemic using assays for recent infection and serotyping among new HIV diagnoses: experience after 2 years in France. J. Infect. Dis. 196:377–383. 10.1086/519387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Vu S, Le Strat Y, Barin F, Pillonel J, Cazein F, Bousquet V, Brunet S, Thierry D, Semaille C, Meyer L, Desenclos JC. 2010. Population-based HIV-1 incidence in France, 2003–08: a modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:682–687. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barin F, Meyer L, Lancar R, Deveau C, Gharib M, Laporte A, Desenclos J-C, Costagliola D. 2005. Development and validation of an immunoassay for identification of recent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections and its use on dried serum spots. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4441–4447. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4441-4447.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Vu S, Meyer L, Cazein F, Pillonel J, Semaille C, Barin F, Desenclos J-C. 2009. Performance of an immunoassay at detecting recent infection among reported HIV diagnoses. AIDS 23:1773–1779. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d8754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barin F, Plantier J-C, Brand D, Brunet S, Moreau A, Liandier B, Thierry D, Cazein F, Lot F, Semaille C, Desenclos J-C. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus serotyping on dried serum spots as a screening tool for the surveillance of the AIDS epidemic. J. Med. Virol. 78(Suppl 1):S13–S18. 10.1002/jmv.20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plantier JC, Damond F, Lasky M, Sankalé JL, Apetrei C, Peeters M, Buzelay L, M'Boup S, Kanki P, Delaporte E, Simon F, Barin F. 1999. V3 serotyping of HIV-1 infection: correlation with genotyping and limitations. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 20:432–441. 10.1097/00042560-199904150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111–120. 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chalmet K, Staelens D, Blot S, Dinakis S, Pelgrom J, Plum J, Vogelaers D, Vandederckhove L, Verhofstede C. 2010. Epidemiological study of phylogenetic transmission clusters in a local HIV-1 epidemic reveals distinct differences between subtype B and non-B infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:262. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cazein F, Le Strat Y, Pillonel J, Lot F, Bousquet V, Pinget R, Le Vu S, Brand D, Brunet S, Thierry D, Leclerc M, Benyelles L, Couturier S, Da Costa C, Barin F, Semaille C. 2011. Dépistage du VIH et découvertes de séropositivité, France, 2003-2010. Bull. Epidémiol. Hebd. 43-44:446–454. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semaille C, Barin F, Bouyssou A, Peytavin G, Guinard J, Le Vu S, Pillonel J, Spire B, Velter A. 2013. High viral loads among HIV-positive MSM attending gay venues: implications for HIV transmission. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 63:e122–e124. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829002ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dachraoui R, Brand D, Brunet S, Barin F, Plantier JC. 2008. RNA amplification of the HIV-1 Pol and env regions on dried serum and plasma spots. HIV Med. 9:557–561. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yerly S, Junier T, Gayet-Ageron A, Amari EB, von Wyl V, Günthard HF, Hirschel B, Zdobnov E, Kaiser L, Swiss HIV Cohort Study 2009. The impact of transmission clusters on primary drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection. AIDS 23:1415–1423. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d40ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laeyendecker O, Brookmeyer R, Cousins MM, Mullis CE, Konikoff J, Donnell D, Celum C, Buchbinder SP, Seage GR, III, Kirk GD, Mehta SH, Astemborski J, Jacobson LP, Margolick JB, Brown J, Eshleman SH. 2013. HIV incidence determination in the United States: a multiassay approach. J. Infect. Dis. 207:232–239. 10.1093/infdis/jis659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brookmeyer R, Laeyendecker O, Donnell D, Eshleman SH. 2013. Cross-sectional HIV incidence estimation in HIV prevention research. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 63:S233–S239. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986fdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longosz AF, Mehta SH, Kirk GD, Margolick JB, Brown J, Quinn TC, Eshleman SH, Laeyendecker O. 2014. Incorrect identification of recent HIV infection in adults in the United States using a limiting-antigen avidity assay. AIDS 28:1227–1232. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyo S, LeCuyer T, Wang R, Gaseitsiwe S, Weng J, Musonda R, Bussmann H, Mine M, Engelbrecht S, Makhema J, Marlink R, Baum M, Novitsky V, Essex M. 2014. Evaluation of the false recent classification rates of multiassay algorithms in estimating HIV type 1 subtype C incidence. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 30:29–36. 10.1089/aid.2013.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leoz M, Chaix M-L, Delaugerre C, Rivoisy C, Meyer L, Rouzioux C, Simon F, Plantier J-C. 2011. Circulation of multiple patterns of unique recombinant forms B/CRF02_AG in France: precursor signs of the emergence of an upcoming CRF B/02. AIDS 25:1371–1377. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328347c060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leoz M, Feyertag F, Charpentier C, Delaugerre C, Wirden M, Lemee V, Plantier J-C. 2013. Characterization of CRF56_cpx, a new circulating B/CRF02/G recombinant form identified in MSM in France. AIDS 27:2309–2312. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283632e0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]