Abstract

The rapid expansion of molecular screening libraries in size and complexity in the last decade has outpaced the discovery rate of cost-effective strategies to single out reagents with sought-after cellular activities. In addition to representing high-priority therapeutic targets, intensely studied cell signaling systems encapsulate robust reference points for mapping novel chemical activities given our deep understanding of the molecular mechanisms that support their activity. In this chapter, we describe strategies for using transcriptional reporters of several well-interrogated signal transduction pathways coupled with high-throughput biochemical assays to fingerprint novel compounds for drug target identification agendas.

Keywords: Small-molecule screening, RNAi, Luciferase assay, Wnt, TP53, Kras, Dot blotting

1 Introduction

Phenotypic screens in cultured cells incorporating large molecular libraries constitute a workhorse discovery platform that has been successfully used for gene discovery in diverse cellular processes. Unlike in vitro strategies that are typically designed for interrogating an isolated mechanism, in vivo approaches can measure a multitude of cellular phenomena that manifest as changes in a given endpoint readout. Thus, cellular reporters can be exploited to identify unanticipated mechanisms of action that can be targeted for therapeutic goals or unwanted activities associated with a given chemical reagent.

Current approaches aimed at capturing all cellular responses to a given genetic or chemical perturbation (a systems biology-based perspective) are not cost-effective solutions for screening large molecular libraries. For example, genome-scale expression profiling strategies reveal transcriptional changes in response to a given intervention that can then be used to infer the affected cell biological process. Whereas such methods can potentially better inform chemical selection processes at the initial screening step, they are slow to progress for screening purposes and beyond the economic reach for a minimally sized screening library. The additional requirement for computational infrastructure to establish functional relationships from such large datasets further imposes limitations to general accessibility.

Collapsing complex cellular phenomenon into the activity of a limited number of reporters enables cost-effective fingerprinting of large molecular libraries [1, 2]. These reporters can be selected for their sensitivity to a broad range of perturbations or for their specificity for a particular cellular process. The fingerprints of each chemical can then be matched to those of reference reagents targeting cellular components with assigned cellular roles to identify shared modes of action. In this manner, desirable and unwanted cellular targets can be defined early in the molecular library screening process, thus ultimately yielding a more robust collection of candidate genes or small molecules.

In this chapter, we build on a strategy previously used to interrogate the Wnt and Hedgehog signal transduction pathways with large chemical and siRNA libraries [3–5]. The approach incorporates luciferase-based reporters for several intensely studied signal transduction pathways that can be deployed in a single screening platform or sequentially to delineate chemical/gene activity (Fig. 1). We describe strategies for maximizing information recovery from this approach using novel reagents with selective activity against different luciferase enzymes (one secreted and two intracellular) as well as high-throughput biochemical analysis of cellular lysates expended for reporter-based activities by dot-blotting, a technique that enables Western blot analysis of high-density protein sample arrays (see Note 1).

Fig. 1.

A multiplexed luciferase reporter and biochemical platform for fingerprinting molecular libraries. A cell line transiently or stably harboring reporter plasmids for monitoring Wnt/β-catenin, p53, and Ras activity forms the basis for screening large molecular libraries to identify novel points of therapeutic intervention or detecting off-targeting effects of reagents. RL Renilla luciferase, FL firefly luciferase, CL Cypridina luciferase. SuperTopFlash reporter incorporates TCF/LEF-binding elements, thus reporting Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity [12]. The Elk-1 reporter system measures an output of Ras signaling and the pp53-TA-Luc plasmid reports TP53 activity. The Cytotox Fluor assay monitors the release of a cytoplasmic protease from cells with compromised membrane integrity. Molecular screening library reagents include small molecules and pooled siRNAs

2 Materials

2.1 Cell Culture and Reporter Constructs

HCT116 cells, colorectal cancer cell line (ATCC).

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM): Prepare full medium with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin.

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

0.25 % Trypsin-EDTA.

8XTCF-Renilla luciferase (RL) reporter construct is generated by inserting Tcf response elements and minimal promoter from STF (Addgene plasmid 12456) into the pGL4.71 vector (Promega).

pp53-TA-Luc plasmid (Agilent Technologies).

Elk1-Gal4 and UAS-CL vector (Elk-1 reporter system, Agilent Technologies).

2.2 Transient Transfection

Reporter DNA stock solution: Prepare 1 mL of a DNA reporter stock solution by combining 300 µL of p53-Firefly luciferase (FL), 300 µL of 8XTCF-Renilla luciferase (RL), 300 µL of Elk1-Gal4, 60 µL UAS-Cypridina luciferase (CL), and 40 µL of water to achieve a final 5:5:5:1 ratio of reporters. The final total DNA concentration of this stock solution is 0.96 mg/mL.

Fugene 6 Transfection Reagent (Promega).

2.3 Luminescence Detection

96-Well white solid plates.

Cypridina luciferase (CL) assay reagents.

Dual-Glo Luciferase Reagent (Promega): Contains 5× passive lysis buffer, luciferase assay reagent II, and Stop & Glo Reagent.

2.4 Dot Blotting

Nitrocellulose membrane.

Gel blotting paper.

PBS-Tween (PBS-T): Add Tween-20 to PBS to a final concentration of 0.1 %.

Blocking buffer: Add nonfat milk to a final concentration of 5 % in PBS-T.

Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)/infrared dye-conjugated secondary antibodies.

P53 antibody (Santa Cruz) and β-actin antibody (Sigma).

Chemiluminescence detection kit (Thermo Scientific, ABC Scientific, Amresco, etc.).

3 Methods

The presented protocol simultaneously monitors the activity of three cancer-relevant cellular processes: the p53, Kras, and Wnt signal transduction pathways using a luciferase-based transient transfection protocol (see Notes 2 and 3).

3.1 Reporter Transient Transfection

The following protocol is written for a small-scale chemical screen that interrogates a library consisting of 1,000 chemical features (see Note 4). To improve signal uniformity across high-density cell culture plates, cells are transfected in culture dishes in bulk and replated into 96-well plates the following day.

3.1.1 Transfecting Cells in Bulk

Use 96-well conical bottom PCR plates to prepare multiple transfection mix pools. Using a 96-well plate will facilitate ease of pipetting and organization overall. In order to screen a 1,000-compound library, use 72 transfection mix pools (six transfection mix pools per plate) and transfect cells sufficient to plate twelve 10 cm2 dishes (in other words 72 wells of the PCR plate) (see Note 5).

Dilute reporter DNA stock solution to 0.02 µg/µL in DMEM. For transfecting twelve 10 cm2 dishes use 3.6 mL of diluted DNA reporter stock solution (see Note 6).

Dilute the transfection reagent Fugene 6–60 µL/mL in DMEM for generating 3,600 µL of diluted Fugene 6 solution.

Add 50 µL of the diluted DNA reporter stock solution per well into 72 wells of PCR plate. Add 50 µL of the diluted transfection reagent into each of the wells. Incubate for 10 min (see Note 7).

During the 10 min required to complete the formation of the DNA/transfection reagent mixes, prepare the cells for transfection (see Subheading 3.1.1, step 4) (see Note 8).

Wash nine 10 cm2 plates of 80–90 % confluent HCT116 cells with 10 mL of PBS and then harvest cells using 1 mL of 0.25 % trypsin followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 min for transfecting sufficient cells for plating 12 × 10 cm2 plates. Neutralize the suspended cells with 10 mL of medium per plate.

Transfer 90 mL of trypsinized and neutralized cells into two 50 mL conical tubes and centrifuge at 130 × g for 5 min, remove the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellets in 90 mL per tube of full culture medium.

Add 7 mL of cells to each 10 cm2 culture dish; prepare 12 dishes.

Add 600 µL of transfection mix dropwise to each of the twelve 10 cm2 plates containing HCT116 cells. Repeat this step for the 12 plates.

Incubate the cells treated with transfection mix at 37 °C in an incubator with 5 % CO2 for 24 h.

3.2 Replating Transiently Transfected Cells into High-Density Cell Culture Plates

Wash the twelve 10 cm2 plates of transfected cells (now at 80–90 % confluency) with 10 mL of PBS and then harvest the cells with 1 mL of 0.25 % trypsin.

Transfer the suspended and neutralized cells into three 50 mL conical tubes and centrifuge at ~130 × g for 5 min, remove the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellet in 120 mL medium.

Using a cell counter, generate a cell solution with 1.0 × 105 cells/mL to yield a 360 mL cell suspension. Plate 1.0 × 104 cells by adding 100 µL of cell solution to each well of a 96-well cell culture plate using a microplate liquid dispenser. The cell suspension should be sufficient in this case for plating 36 × 96-well plates.

Incubate the plates at 37 °C in an incubator with 5 % CO2 for 4 h to allow the cells to re-adhere.

The compounds to be tested should be at a stock concentration of 250 µM in order to reach a final concentration of 2.5 µM. If not, dilute the chemicals to this concentration by using vehicle (DMSO in this case here).

Transfer 1 µL per well of the chemicals to each well of the 96-well plate containing the cells. As each chemical will be tested in triplicate, add the same chemicals to two additional 96-well plates containing cells.

Treat the cells with the compounds for 36 h in a standard CO2 cell incubator at 37 °C. This incubation time suggested here is primarily based upon prior experiences with luciferase reporter-based chemical screens in cultured cells that yielded successful outcomes. This parameter can be adjusted to accommodate the speed of cell doubling for a given cell line of interest (which will dilute out the transfected reporter) as well as the ability to robustly detect the effects of a positive chemical control.

3.3 Luciferase Assays

After 36 hrs luciferase activities are measured. The endpoint should of course be optimized for the specific cell line and readouts used (see Notes 9 and 10). In our study, a 36-h incubation time should yield a robust signal (see Note 11). This study incorporates multiple reporters, one secreted into the culture medium, and two others expressed in the cell cytoplasm, so obtain measurements from both the culture medium and cellular lysate (see Note 12).

3.3.1 Detection of CL Activity in the Culture Medium

Transfer 20 µL of culture medium from the assay plated in Subheading 3.2 to a white opaque 96-well plate using a liquid handler.

Add 20 µL of Cypridina luciferin assay buffer to each well.

Add 10 µL of Cypridina luciferin substrate to each well and detect CL activity immediately using a luminometer (see Notes 13–15). Note that the suggested manufacturer’s protocol for the detection CL differs from a typical luciferase detection system (say for FL) in that it requires the addition of buffer to samples prior to the addition of the substrate.

3.3.2 Detection of FL and RL Activity

Remove the culture medium and then lyse the cells. Add 30 µL/well of 1× passive lysis buffer to each well of cells using a microplate liquid dispenser and place on a platform rocker set at a medium rocking speed for 5 min at room temperature.

Add 10 µL of the luciferase assay reagent II per well and immediately measure FL activity using the luminometer (see Note 16).

After measuring FL activity, this signal will be simultaneously blocked and RL substrate added by the addition of 10 µL of Stop & Glo Reagent per well. After measuring RL activity retain the lysate for additional biochemical assays.

3.4 Biochemical Assays

To increase content recovery, a biochemical component that complements the luciferase reporter-based readouts is incorporated in the overall drug discovery platform. The following protocol describes how the lysate from a single 96-well plate is transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blotting using a 96-well dot-blotting device (a dot blotter).

Pre-wet a 90 × 130 mm nitrocellulose membrane in PBS for 30 s. Place the membrane squarely onto sheets of blotting paper cut to the same size pre-wetted with PBS. Clamp the nitrocellulose and blotting paper assembly between the upper and lower modules of the dot blotting apparatus (BioRad and Millipore both sell popular models). By tightening the screws on all four corners of the apparatus, individual watertight chambers for accommodating 96 different samples are generated. Attach the apparatus to a vacuum source using appropriate tubing.

Pre-rinse the membrane by adding 100 µL of PBS to each well using a multichannel pipette and applying vacuum at 5 PSI.

Prepare the lysate subjected to luciferase activity measurements for binding to nitrocellulose by adding 60 µL of 1× passive lysis buffer to each well of lysate using the microplate liquid dispenser and then transferring 30 µL of lysate onto the nitrocellulose membrane using the 96-channel liquid handler. A tip touch to the side of the well will improve volume-dispensing consistency across all wells (programmable with some 96-well liquid handlers).

Allow the lysate to slowly filter through the membrane by gravity for 10 min and then briefly apply vacuum to the manifold (5 PSI) to complete the transfer.

Wash the nitrocellulose membrane with 200 µL of PBS again by applying vacuum filtration.

Remove the membrane from the apparatus and incubate in blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature to prevent nonspecific antibody binding.

Wash with PBS-T for 10 min three times.

Incubate the nitrocellulose membrane with mouse p53 antibody diluted to 1:1,000 in PBS-T for 60 min at room temperature.

Wash with PBS-T for 10 min three times.

Incubate with anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in PBS-T.

Incubate the nitrocellulose membrane with rabbit β-actin antibody diluted to 1:10,000 in PBS-T for 60 min at room temperature.

Wash with PBS-T for 10 min three times.

Incubate with anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with an infrared fluorescent dye (IRDye 800CW, for example) diluted in PBS-T for 60 min at RT in the dark.

Wash with PBS-T for 10 min three times.

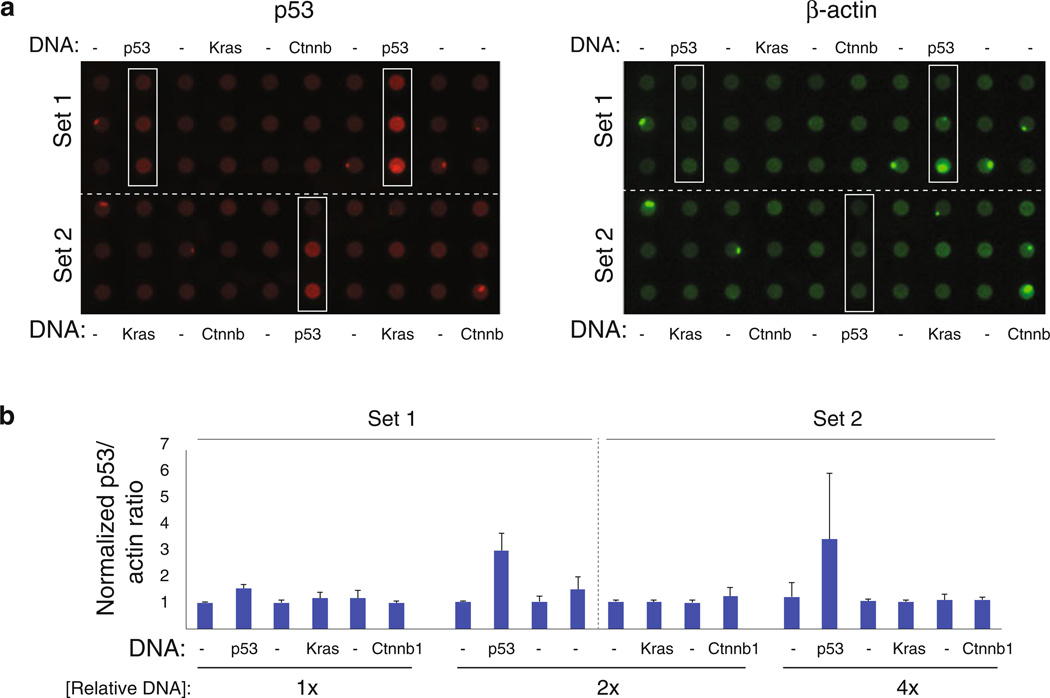

Incubate the membrane with chemiluminescence detection reagents for 1 min to detect HRP-generated signal. Acquire both HRP- and infrared dye-generated signals using a Li-COR Odyssey Fc instrument (Fig. 2) (see Note 1). A predefined optimal wavelength of excitation will be used to detect the respective infrared dye conjugated to the secondary antibody. In the case of the IRDye 800CW secondary, an excitation wavelength of 800 nM is used.

Fig. 2.

Increasing content recovery by coupling luciferase-based assays with high-throughput biochemical readouts. The same cell line subjected to the luciferase-based assay protocol (HCT116 cells) is evaluated here for its reliability in reporting a biochemical readout (p53 expression) by dot blot analysis. Cells transfected with indicated expression construct and pathway reporters in a 96-well culture plates were lysed 48 h posttransfection. Following luciferase activity measurements (data not shown), protein from spent lysates was immobilized on nitrocellulose using a liquid handler and filtration manifold. (a) p53 and β-actin protein levels detected using protein-specific antibodies, infrared fluorescent dye-coupled secondary antibodies (with emissions at 680 and 800 nM), and the Li-COR imaging system. Columns of lysate corresponding to cells transfected with p53 DNA are boxed. (b) Quantification of the p53 to β-actin protein ratio

3.5 Interpreting Screening Results and Improving the Next Screen

Statistical means to identify outlier phenomenon rank-order screening results are based on reproducibility but not their potential biological relevance. Nevertheless, identifying robust effects of protein perturbation by genetic or chemical means is typically the first step towards achieving end-point screening goals. Frequently, a standard deviation threshold of the normalized data relative to the mean is used to identify outliers. The selection of the threshold and the number of hits to be considered for further analysis can be guided by the ability of the algorithm to return (a) known components (controls), (b) useful effects based on secondary counter-screen results/experience, and (c) an economically feasible counter-screen strategy. Below, we briefly discuss issues/strategies that could improve the overall primary dataset such that the challenges just discussed can be minimized [6].

A consistent problem with high-throughput screens that rely on high-density multiwell plates is known as an “edge effect.” This effect is associated with a frequency of outlier results from cells evaluated in wells found on the edge of the plate that is higher than that observed from the remaining wells. To limit the contribution of this phenomenon to the overall selection of hits from a screen, a number of computational approaches can be taken (see [7] for example).

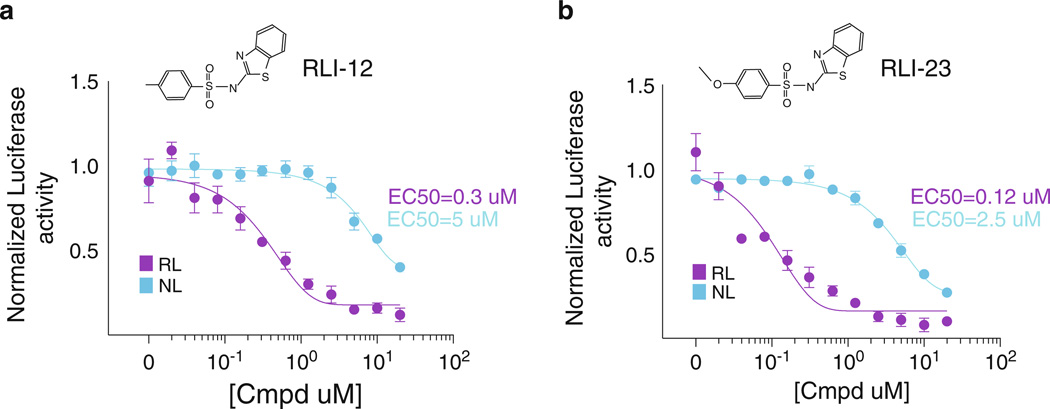

Improvements in the selection of potentially meaningful reagents from a molecular library could also be found in the increase of content return from the initial screening effort. This can be accomplished by utilizing new technologies that afford even greater multiplexing capability than what is described above. For example, luciferase enzymes engineered to emit a signal at a given wavelength could be used to detect specific pathway signals simply by altering the spectral detection parameters of a luminometer. At the same time, the discovery of enzymes that generate luminescence using novel substrates could be leveraged for multiplexing exercises when combined with specific luciferase inhibitors such as those that target RL [8] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Chemically mediated minimization of luciferase enzyme cross talk in multiplexed screening platforms. The RL inhibitors 12 and 23 (RLI12 and RLI23) exhibit >10-fold selectivity for RL over NL. These compounds could be used to eliminate inadvertent release of cytoplasmic RL into the medium where the typically secreted NL activity is found. The RLI compounds were identified as false positives from a high-throughput chemical screen for novel Wnt pathway inhibitors [3, 8]

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the NIH (R01 CA168761), CPRIT (RP130212), and the Welch Foundation (I-1665). This work was also supported by the fund from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for the “Institutional Program for Young Researcher Overseas Visits.”

Footnotes

Combining multiplexed luciferase assays with a dot blotting strategy can greatly expand the number of data points used to generate signatures for each chemical feature found in a screening library. From a single well three dot blots can be produced using the protocol provided above. A Li-COR Odyssey Fc imaging system also provides an additional opportunity to test three antibodies simultaneously or sequentially from the same blot using different infrared- and HRP-coupled secondary antibodies. For this protocol we chose p53 antibody that detects a protein with a wide dynamic range, and β-actin antibody that serves as a loading control.

Stable cell lines harboring p53, Kras, and Wnt pathway reporters can be employed in lieu of transient transfection strategies. Creating a stable cell line that harbors all four DNA plasmids can be challenging. Multiple cell lines each harboring one or two reporters provide an alternate strategy that may increase the success rate of generating such reporter cell lines. For example, one cell line can harbor the p53 and Wnt reporters while another can be used to monitor the Kras pathway. Regardless of the approach, these cell lines likely would provide a more robust screening platform by mitigating transient transfection-associated stochasticism.

A variety of luciferase-based reporters for monitoring diverse cell biological processes are commercially available. For example, luciferase-based reporters of other pathways such as the BMP and Notch pathways can be used for similar multiplexed luciferase screening projects.

We describe here strategies for multiplexing luciferase reporters of various cellular pathways using a small chemical library but it can be easily adapted for large cDNA or siRNA libraries [1].

We suggest achieving a large volume of transfection mix by combining a series of smaller transfection mix reactions using an optimized smaller scale protocol provided by the manufacturer to maintain consistency in transfection efficiency. The use of 96-well conical bottom PCR plates greatly facilitates the preparation of multiple transfection mixes given the accessibility of the samples to multichannel pipettes.

Although more labor intensive and tedious, a multichannel pipettor can also be used to dispense cells into 96-well plates and/or transferring lysate to the dot blotting apparatus. Although not readily accessible to all, a liquid handler with a 96-channel liquid dispensing head would facilitate most liquid transfer procedures. For larger scale screens (beyond 1,000 samples for example), this instrument becomes a necessity.

For this protocol we employed Fugene 6 as the transfection reagent, so dilutions of DNA stocks and transfection reagent should be done in cell culture medium (DMEM) lacking FBS and penicillin/streptomycin as recommended by supplier.

If unable to complete the cell preparation within 10 min of incubation time of DNA/transfection reagent, then neutralize the lipid complex formation reaction by adding full medium (DMEM/10 % FBS/1 % penicillin/streptomycin). Now the trypsinization procedure can be safely completed.

The selection of a small-molecule library relates to its intended purpose: a library with a wider chemical space increases the probability to find a drug-like small molecule although small libraries like natural product libraries can be employed to uncover new biology [9, 10].

The selection of the luciferase enzyme readout can greatly influence the labor, cost, and instrument sensitivity requirements for a given screen. Whereas firefly luciferase is the most commonly used enzyme in commercially available constructs, the advent of new luciferase reporter systems that do not require ATP (as in the case of RL-based reactions) or that incorporate enzymes with greater activity promises to improve the reproducibility and cost-effectiveness of luciferase-based research platform, respectively.

An important note regarding the selection of luciferase reporters in chemical screens is the susceptibility of FL to chemical inhibition that could give rise to false positives [11]. In our experience, enzymes such as Renilla, Gaussia, or Nanoluc luciferase (RL, GL, and NL, respectively) that utilize coelenterazine (a larger substrate than luciferin) are less susceptible to chemical inhibition. Thus, given the opportunity to select or design a reporter construct with a chemical screen in mind, avoidance of FL would be advised.

For high-throughput screens, Z-prime statistical analysis can provide an indication of overall assay robustness based on the average and standard deviation of a positive and negative control. Z-prime values above 0.5 indicate a robust and acceptable assay.

The most frequently used multiplexing luciferase enzymes are FL and RL given the availability of plug-and-play kits for measuring their activities in sequence. A standard protocol typically entails adding luciferin to cell lysates to reveal levels of FL activity followed by a quenching reagent that is simultaneously deposited with coelenterazine to yield a secondary RL signal. With the addition of other luciferases that can be secreted such as GL or that use yet another substrate such as Cypridina luciferase (CL), the number of approaches available for generating high-content data using luciferase enzymes continues to grow.

Other reporter systems can be incorporated into this protocol to increase the content of this experiment. For example, the CytoTox Fluor assay can be used to monitor cellular toxicity by sampling the levels of an intracellular protease released into the culture medium. The addition of the CytoTox assay reagent does not influence the activity of the CL reporter.

Commercially available CL assay kits consist of two parts, assay buffer and reconstituted substrate. Since for a screen a large number of plates are used, after addition of assay buffer to cell media, media and assay buffer-containing plates can be stored at 4 °C while the rest of the plates are processed.

In a luciferase assay a flash of light is generated that decays rapidly after the enzyme and substrates are combined. For this reason, the use of “flash kits” requires rapid measurement within 5 min upon substrate addition and since a screen requires processing large numbers of plates, a luminometer coupled with an automated plate stacker is also required unless luciferase kits optimized for extended signal duration are used.

References

- 1.Kulak O, Lum L. A multiplexed luciferase- based screening platform for interrogating cancer-associated signal transduction in cultured cells. J Vis Exp. 2013;77:e50369. doi: 10.3791/50369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potts MB, et al. Using functional signature ontology (FUSION) to identify mechanisms of action for natural products. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra90. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen B, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob LS, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals disease-associated genes that are common to Hedgehog and Wnt signaling. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang W, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen for Wnt/beta-catenin pathway components identifi es unexpected roles for TCF transcription factors in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9697–9702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804709105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birmingham A, et al. Statistical methods for analysis of high-throughput RNA interference screens. Nat Methods. 2009;6:569–575. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong R, et al. SbacHTS: spatial background noise correction for highthroughput RNAi screening. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2218–2220. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lum LD, Kulak O. Multiplexed luciferase reporter assay systems. #12/908,754. US Patent. 2012

- 9.Hasson SA, Inglese J. Innovation in academic chemical screening: fi lling the gaps in chemical biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frearson JA, Collie IT. HTS and hit fi nding in academia: from chemical genomics to drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:1150–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan C. Doubts raised over ‘readthrough’ Duchenne drug mechanism. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:771–773. doi: 10.1038/nbt0913-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veeman MT, et al. Zebrafi sh prickle, a modulator of noncanonical Wnt/Fz signaling, regulates gastrulation movements. Curr Biol. 2003;13:680–685. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]