Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) circulating recombinant form 08_BC (CRF08_BC), carrying the recombinant reverse transcriptase (RT) gene from subtypes B and C, has recently become highly prevalent in Southern China. As the number of patients increases, it is important to characterize the drug resistance mutations of CRF08_BC, especially against widely used antiretrovirals. In this study, clinically isolated virus (2007CNGX-HK), confirmed to be CRF08_BC with its sequence deposited in GenBank (KF312642), was propagated in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with increasing concentrations of nevirapine (NVP), efavirenz (EFV), or lamivudine (3TC). Three different resistance patterns led by initial mutations of Y181C, E138G, and Y188C were detected after the selection with NVP. Initial mutations, in combination with other previously reported substitutions (K20R, D67N, V90I, K101R/E, V106I/A, V108I, F116L, E138R, A139V, V189I, G190A, D218E, E203K, H221Y, F227L, N348I, and T369I) or novel mutations (V8I, S134N, C162Y, L228I, Y232H, E396G, and D404N), developed during NVP selection. EFV-associated variations contained two initial mutations (L100I and Y188C) and three other mutations (V106L, F116Y, and A139V). Phenotypic analyses showed that E138R, Y181C, and G190A contributed high-level resistance to NVP, while L100I and V106L significantly reduced virus susceptibility to EFV. Y188C was 20-fold less sensitive to both NVP and EFV. As expected, M184I alone, or with V90I or D67N, decreased 3TC susceptibility by over 1,000-fold. Although the mutation profile obtained in culture may be different from the patients, these results may still provide useful information to monitor and optimize the antiretroviral regimens.

Introduction

Circulating recombinant form (CRF) 08_BC (CRF08_BC) is one of the most prevalent CRFs in China.1,2 It was first isolated from injecting drug users (IDUs) in Guangxi province in 1997. Thereafter it emerged in Yunnan province and spread to South China through heroin trafficking routes.3–5 CRF08_BC transmission was responsible for a large number of new infections in IDUs. A molecular epidemiology study showed that CRF08_BC was the dominant subtype (59.8%) in Yunnan Province in the newly reported cases.6 From 2007 to 2010, CRF08_BC accounted for over 40% of HIV-1 infections in Chinese blood donors.7 In addition to IDUs, this CRF also spread through heterosexual contacts and predominated among heterosexuals in Yunnan Province.6

Currently 26 antiretroviral agents using six different mechanisms of action have been licensed for the treatment of HIV infections in adults, half of which target the reverse transcriptase (RT).8 RT inhibitors (RTIs) include nine nucleoside RTIs (NRTIs) and four nonnucleoside RTIs (NNRTIs). Currently, four NRTIs of lamivudine (3TC), zidovudine (AZT), stavudine (d4T), and didanosine (ddI), two NNRTIs of nevirapine (NVP) and efavirenz (EFV), and one protease inhibitor, indinavir (IDV), are provided free by the Chinese government.9 In China, antiretroviral therapy is always composed of NVP, 3TC, and d4T or AZT, of which the NVP-based regiment is the most popular drug combination while 3TC serves as the NRTI backbone in first-line treatment and is included in a second-line regiment after first-line treatment failure.10 EFV is an alternative choice for the NNRTI-based regiment in first-line treatment in China.

Because of the above reasons, NVP, EFV, and 3TC were selected for the in vitro resistance studies for CRF08_BC. Antiretroviral (ARV) treatment has significantly reduced HIV-related morbidity and mortality, but one of the potential problems is the emergence of drug resistance. Our current knowledge of drug resistance is mainly derived from HIV-1 subtype B, which accounts for only 12% of HIV-1 infections in the world. Our knowledge regarding non-B subtypes and CRFs remains poorly characterized.11,12

Studies of HIV-1 RT genotype and phenotype patterns in ARV-naive and treatment failure patients in China are increasing but are still limited.13,14 Although limited information on drug resistance in the newly emerged CRF08_BC has been obtained from treatment-naive patients,15 there is still no published information on drug resistance mutation patterns after ARV exposure. In this study, we selected drug-resistant variants of CRF08_BC by in vitro passage in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with escalating concentrations of NVP, EFV, and 3TC, respectively. The results showed that RTI-resistant virus strains could develop in the in vitro culture system. Knowledge concerning these resistance mutations in CRF08_BC and their effects on drug susceptibility may be valuable in optimizing the design of ARV regimens in patients infected with CRF08_BC.

Materials and Methods

Virus strain and compound

A virus strain (2007CNGX-HK) of CRF08_BC was originally isolated from an anonymous intravenous drug user (IDU) living in Guangxi Province in 2007 as previously described.16 The patient was symptomatic and diagnosed in the same year.16 The isolated virus was quantified by a blue focus units (BFU) assay as described previously. Briefly, virus stock was 3- to 10-fold serially diluted with DMEM complete culture medium containing 25 μg/ml 2-diethylaminoethanol (DEAE) and inoculated to TZM-bl cells seeded in a 96-well plate. The infected cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h and stained with X-Gal solution. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the blue cells were easily visualized and counted under light microscopy. EFV, 3TC, and NVP were provided by Merck Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ), GlaxoSmithKline (Philadelphia, PA), and Boehringer Ingelheim (Ridgefield, CT), respectively. All the drugs were dissolved in DMSO and stored at −20°C until use.

Full viral genomic sequence analysis

Viral RNA extraction, cDNA syntheses, nearly full length genome recovery, and sequencing were performed according to our previous study.17 Virus coding sequences (CDSs) were identified by online software HIV Sequence Locator. The REGA HIV-1 Subtyping Tool (Version 2.0) and Recombinant Identification Program (RIP) were used to confirm the virus subtypes.18 Genotypic resistance interpretation was also done using the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database HIVdb program (version 6.0.11) (http://hivdb.stanford.edu). The viral genome sequence was annotated and deposited into GenBank (accession number: KF312642). 2007CNGX-HKV was used to represent the viral genome of virus strain 2007CNGX-HK.

In vitro selection of CRF08_BC-resistant variants to RTI

The isolated virus strain 2007CNGX-HK was used for in vitro selection of virus variants resistant to NVP, EFV, and 3TC, respectively, according to the methods described previously.17,19 Briefly, PBMCs (1×106) were initially infected with 2×105 BFU/well of the virus in a 24-well tissue culture plate (in quintuple) and cultured in 1 ml medium containing diluted RTI. The starting and ending culture concentrations were 1 nM and 128 μM for NVP, 0.04 nM and 2 μM for EFV, and 0.1 μM to 64 μM for 3TC, respectively. One untreated well was included as a negative control. At days 3, 7, and 10 postinfection, virus titers in the culture supernatant of each well were detected by BFU assay. Once the BFU number in drug-treated cultures was more than 20% of the untreated control, the drug concentration was increased 2-fold. When the BFU number in drug-treated cultures was less than 5% of the untreated control, the selection was restarted. The selection for NVP, EFV, and 3TC was carried out for 40, 30, and 22 passages, respectively. One passage was around 10 days. Passages were performed with the supernatant of the preceding passage and conducted using the same rules as mentioned above. To monitor the development of the accessory mutations under the pressure of NVP, virus variants that developed known primary mutations were subcultured in duplicate or quadruplicate. Culture supernatants of each passage were also saved for genotypic and phenotypic resistance analyses.

Genetic analysis of resistant variants

Viral RNA was extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse transcribed to cDNA with SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the user manual. The entire protease gene and the first 440 codons of the RT gene were amplified from viral cDNA by high fidelity AccuPrime Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) with primer AV150 (5′-GTG GAA AGG AAG GAC ACC AAA TGA AAG-3′) and polM4 (5′-CTA TTA GCT GCC CCA TCT ACA TA-3′) as previously described.20,21 PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and analyzed on 1% TBE agarose gel to confirm their size and purity. After purification, PCR products were directly sequenced in both directions using the Big Dye terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequence results of each sample were aligned and edited with the Staden Package22 and submitted to the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database HIVdb program (version 6.0.11) (http://hivdb.stanford.edu) for genotypic resistance interpretation.23,24

Phenotypic analysis of drug-resistant variants

Phenotypic analysis was performed in TZM-bl cells containing the luciferase reporter gene induced by HIV infection as previously described.25 Briefly, the TZM-bl cells in a 96-well culture plate were infected with 400–600 BFUs/well of the virus and then added with seven serial dilutions of RTIs in triplicate. After 48 h of culture, luciferase activities were tested by the luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) of each drug was determined from the curves plotted by the percentage of reduction of luciferase activity against serial drug concentrations. RTI resistance of virus variants was expressed as the fold change (FC) of RTI EC50. The RTI susceptibility fold change of virus variants was defined as the ratio between the EC50 of drug-resistant variants with the mutations and the EC50 of virus without the mutations.

The results have not only been compared to the mutation profiles in several in vitro selection studies of subtype B virus and the mutations summarized from large number of clinical patients in previous studies, but have also been compared to the resistance mutations displayed in the HIV drug resistance database of Stanford University, in which the extensively studied subtype B and the most widely spread subtype C are the most important component parts.

Results

Viral genome analysis

The nearly full length viral genome (8,962 bp) except for the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) of strain 2007CNGX-HK was obtained. According to the indications of the online software HIV Sequence Locator, the viral sequence (2007CNGX-HKV) contained all the known viral genes, including gag, pol, vif, vpr, tat, rev, vpu, env, and nef coding for viral proteins p17, p24, p2, p1, p6, PR, RT, IN, Vif, Vpr, Tat, Rev, Vpu, gp120, gp41, and Nef, respectively. RT was located in 1,870–3,189 bp of 2007CNGX-HKV. The Rega HIV-1 subtyping tool (version 2.0) showed that 2007CNGZ-HKV belonged to HIV-1 CRF08_BC as determined by both phylogenetic and bootscanning methods (Fig. 1). We find that most of 2007CNGX-HKV was from subtype C except for small segments that were contributed by subtype B. The mosaic structures of subtype B and C in both 2007CNGX-HKV and the reference strain of CRF08_BC (CNGX-6) were confirmed by RIP software and the recombinant profile of 2007CNGX-HKV was similar to the reference strain CNGX-6. Three segments from subtype B were found in the subtype C backbone and the recombination points located at positions in the Gag, RT, and nef regions of 2007CNGX-HKV and CNGX-6, respectively. Preexisting drug-resistant mutations in the PR and RT genes of 2007CNGX-HKV were analyzed by the Genotypic Resistance Interpretation Algorithm. No NRTI or NNRTI mutation was found and the virus would be susceptible to RTIs. Thus, 2007CNGX-HK was considered to be a representative member of CRF08_BC and was used for in vitro selection to investigate the NVP, EFV, and 3TC mutation profile.

FIG. 1.

Subtyping analysis of the virus genome of 2007CNGX-HKV using the Rega HIV-1 subtyping tool (version 2.0). The recombination pattern was determined by comparing the 2007CNGX-HKV sequence with reference sequences of HIV-1 pure subtypes A, B, C, D, F, G, H, J, and K. Subtype B DNA segments were found to be integrated into the genomic backbone of subtype C by phylogenetic methods of the Rega HIV-1 subtyping tool. The result was displayed as a virus genomic structure figure with subtype components (A). For subtype recombination analysis, reference sequences of different pure subtypes and circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) were further applied for the comparison of the virtually full-length sequence of 2007CNGX-HKV by bootscanning methods. Bootscan analysis showed that 2007CNGX-HKV belonged to CRF08_BC (B).

RTI-associated mutations and combination profiles of CRF08_BC generated in vitro

To characterize the resistance of CRF08_BC to RTI, virus variants of 2007CNGX-HK with drug-associated mutations were selected in vitro by serial passages with increasing concentrations of NVP, EFV, and 3TC, respectively. After around 40 passages of PBMC cultures in the presence of NVP, three combination profiles of mutations were identified (Fig. 2). These profiles were initialed by three previously reported mutations Y181C, E138G, and Y188C,26–28 whereas 13 HIVdb program predicted mutations ,V108I, G190A, H221Y, V106A, F116L, V106I, N348I, K101R, V90I, D67N, E138R, F227L, and K101E,29–35 six HIVdb program unpredicted mutations, K20R, T369I, E203K, A139V, V189I, and D218E,36–39 and seven novel mutations, E396G, S134N, Y232H, L228I, D404N, C162Y, and V8I, appeared gradually and formed combinations of up to four to six mutations at the end of the selection. Two combination profiles led, respectively, by two well-known mutations of L100I and Y188C were selected by EFV.40 To the end of the selection, two HIVdb program predicted mutations V106L and F116Y, and a previously reported but HIVdb program unpredicted mutation A139V,41,42 were accumulated to form the EFV combination profiles. 3TC induced only one combination profile headed by M184I and accompanied, respectively, by D67N and V90I.

FIG. 2.

Combination profiles of mutations selected by reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs) in CRF08_BC strain 2007CNGX-HK. Mutations that are bolded are novel mutations. Three different combination profiles initially that emerged with mutations Y181C, E138G, and Y188C were selected by nevirapine (NVP), while two distinct mutation profiles led by L100I and Y188C were induced by efavirenz (EFV) in CRF08_BC strain 2007CNGX-HK. Only one mutation profile dominated by M184I emerged in the lamivudine (3TC) selection cultures. NVP selected virus variants with known primary mutations (Y181C, E138G, and Y188C) were subcultured in duplicate or quadruplicate. Population sequencing was adopted for genotyping. Mutations in variants were detected in a viral pool (viral population). One passage was around 10 days.

The most complicated and diverse mutation profiles were found in NVP, followed by EFV, while the simplest profile was selected by 3TC. Among all the selected mutations in this study, Y188C appeared in both NVP and EFV combination profiles and served as the initial mutation. A139V was also induced by both NNRTIs and emerged as accumulating substitutions. Both V90I and D67N were selected as accompanied mutations by both NVP and 3TC, although they are different kinds of RTIs. Among the NVP-associated mutations, Y181C appeared in different profiles as initial and accessory mutations. V108I and V90I were also accumulated in different profiles but served only as accessory mutations. Between the two EFV-selected mutation profiles, Y188C was found in both profiles but emerged as initial and accompanied mutations, respectively. Figure 2 also shows that different secondary mutations would accumulate by the same initial mutation and followed further by other mutations.

Mutations developed in the RT gene during the selection period are summarized in Table 1, including reported mutations with or without drug resistance prediction by the HIVdb program and novel mutations. Substitutions in the RT gene were compared with the conserved amino acid of subtype B, C, and the CRF08_BC at the same position. Based on the predictions of the HIVdb program and by comparing the sequences between RTI-treated virus variants and wild-type virus, a total of 33 mutations were selected in our study, including 26 reported mutations and seven novel mutations. Twenty-two reported mutations and all the novel mutations were induced by NVP. Five and three known mutations were found in the EFV and 3TC selections, respectively.

Table 1.

Mutations Developed in the Reverse Transcriptase Gene of CRF08_BC Strain 2007CNGX-HK During the In Vitro Selection with Increasing Concentrations of Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

| Mutations predicted by HIVdb program | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67 | 90 | 100 | 101 | 106 | 108 | 116 | 138 | 181 | 184 | 188 | 190 | 221 | 227 | 348 | |

| B, C, 08_BC cons | D | V | L | K | V | V | F | E | Y | M | Y | G | H | F | N |

| NVP | N | I | — | E/R | A/I | I | L | G/R | C | — | C | A | Y | L | I |

| EFV | — | — | I | — | L | — | Y | — | — | — | C | — | — | — | — |

| 3TC | N | I | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | I | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mutations without prediction of HIVdb program | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 139 | 189 | 203 | 218 | 369 | ||||||||||

| B, C, 08_BC cons | K | T,A | V | E | D | T | |||||||||

| NVP | R | V | I | K | E | I | |||||||||

| EFV | — | V | — | — | — | — | |||||||||

| Novel mutation | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 134 | 162 | 228 | 232 | 396 | 404 | |||||||||

| B, C, 08_BC cons | V | S | S,C | L | Y | E | E,D | ||||||||

| NVP | I | N | Y | I | H | G | N | ||||||||

B, C, 08_BC cons, conserved amino acid in subtypes B, C, and CRF08_BC. The conserved amino acids at codons 139 and 162 of subtypes B and C are T and S while those in CRF08_BC strain are A and C. Amino acid at codon 404 in subtype B is E and that in subtype C and CRF08_BC strain is D.

NVP, nevirapine; EFV, efavirence; 3TC, lamivudine.

Resistance patterns selected in the CRF08_BC virus in this study were compared to that reported in the Stanford University HIV drug resistance database. In this database, NNRTI mutation patterns were summarized from 15,832 clinical isolates containing at least one major mutation. For the first 11 most prevalent mutation patterns, four (Y181C, Y181C/G190A, G109A, and K101E/G190A) were detected in this in vitro NNRTI-selected study regardless of nonmajor mutations. Database reported patterns (Y188C, L100I, and Y188C/Y181C) were also found in this study. For the NRTI resistance pattern, 3TC selected profiles (M184I and M184I/D67N) in this work were also reported by the HIV drug resistance database.

Phenotypic analysis of CRF08_BC virus variants selected by RTI

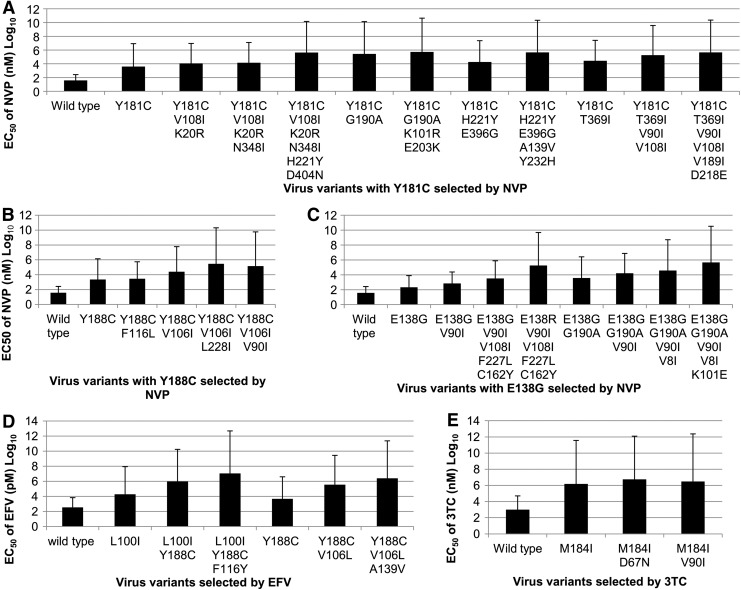

The phenotypes of virus variants selected by different RTIs were determined by susceptibility assays in TZM-bl cells. Among three initial mutations selected by NVP, Y181C showed the highest resistance to NVP, which resulted in about a 105-fold increase in NVP resistance, while the other two initial mutations, Y188C and E138G, reduced NVP susceptibility by 60.9- or 5.7-fold, respectively. In the Y181C-initiated virus variants, the additional mutation G190A and double mutations H221Y/D404N and A139V/Y232H increased NVP resistance by 69.1-, 29.8-, and 25.1-fold, respectively, while virus variants carrying additional mutations T369I, V90I/V108I, and H221Y/E396G showed 7.0-, 6.4-, and 4.6-fold less susceptibility to NVP. The other additional mutations V108I/K20R, V189I/D218E, K101R/E203K, and N348I reduce NVP susceptibility by less than 5-fold (Fig. 3A). For the Y188C-associated NVP mutation profile, virus with substitutions of V106I and L228I increased NVP EC50 by over 10-fold, while accessory mutations V90I and F116L in this profile reduced NVP validity by 5.9- and 1.2-fold, respectively (Fig. 3B). For the mutation pattern led by E138G, additional mutations K101E displayed 12.1-fold less sensitivity to NVP and mutations V108I/F227L/C162Y and V90I increased NVP resistance by about 4-fold. Variants with V8I showed only 2.4-fold reduced susceptibility to NVP. Interestingly, mutation E138R significantly decreased NVP susceptibility by 55.3-fold (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic analysis of CRF08_BC 2007CNGX-HK virus variants selected by NVP, EFV, and 3TC. The RTI EC50 of CRF08_BC virus variants selected by NVP with initial mutation Y181C (A), E138G (B), and Y188C (C), and by EFV (D) and 3TC (E) was determined by phenotypic analysis in TZM-bl cells with serial concentrations of RTIs.

As shown in Fig. 3D, the EFV-induced initial mutations L100I and Y188C conferred about 52.9- and 12.0-fold resistance to EFV, respectively. Surprisingly, Y188C, as an additional mutation after the emergence of L100I, showed strong resistance to EFV with increased EC50 by 50-fold. The additional mutation F116Y reduced virus susceptibility to EFV by 12-fold. After the appearance of the initial mutation Y188C, virus variants carrying V106L had a great impact on virus resistance to EFV (78-fold). Mutation A139V increased virus EC50 to EFV by about 6.9-fold.

In variants selected by 3TC, initial mutation M184I alone strongly reduced the virus susceptibility to 3TC by over 1,000-fold, while additional mutations D67N and V90I showed less than 5-fold increased resistance to 3TC (Fig. 3E). Taken together, a total of 25 NVP-selected, five EFV-selected, and three 3TC-selected mutations in variants of CRF08_BC virus were found to be associated with different levels of drug resistance (Table 2). Based on the results of RTI susceptibility, RTI-selected mutations could be classified as a high (over 20-fold), medium (between 4- and 20-fold), and low (less than 4-fold) level of resistance to NVP. Six NVP-selected mutations or mutation combinations (Y181C, G190A, Y188C, E138R, H221Y/D404N, and A139V/Y232H), three EFV-selected mutations (V106L, L100I, and Y188C), and one 3TC-selected mutation (M184I) resulted in high levels of drug resistance (>20-fold increase). The other 22 mutations in the selected virus variants were associated with medium or low level drug resistance, respectively.

Table 2.

Characterization of Drug Resistance Mutations in CRF08_BC Strain 2007CNGX-HK

| Increased folds of EC50 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | >20 | 4–20 | <4 |

| NVP | E138R | (V90I) | V8I |

| Y181C* | K101E | (V108I)/K20R | |

| G190A | (V106I) | F116L | |

| Y188C* | E138G* | K101R/E203K | |

| A139V/Y232H | (H221Y)/E396G | V189I/D218E | |

| (H221Y)/D404N | T369I | N348I | |

| L228I | |||

| (V90I)/(V108I) | |||

| (V108I)/F227L/C162Y | |||

| EFV | L100I* | F116Y | |

| V106L | A139V | ||

| (Y188C) | Y188C* | ||

| 3TC | M184I* | V90I | |

| D67N | |||

Novel mutations are in bold. Initial mutations are labeled with an asterisk (*). Mutations in parentheses appeared in different mutation profiles/patterns. Mutations underlined were selected by different drugs.

Out of five initial mutations (Y181C, E138G, Y188C, L100I, and M184I), four were associated with a high level of drug resistance and one (Y188C) was selected by both NVP and EFV treatments. Novel mutations Y232H and D404N in combination with other mutations A139V or H221Y reduced NVP susceptibility over 20-fold, while other novel mutations V8I, C162Y, L228I, and E396G each alone or in combination with other mutations showed less than 20-fold increased resistance to NVP.

Drug resistance effects of the HIVdb predicted mutations in CRF08_BC virus in this study were further compared with that reported in the Stanford University HIV drug resistance database43 (Table 3). Mutations K101E, V106M, V108I, Y181C, Y188C, M184I, and G190A in CRF08_BC were associated with RTI resistance similar to that reported in the database, but V106I and L100I in CRF08_BC might be related to a resistance to NVP or EFV higher than that reported in the database. Furthermore, the drug resistance effects of F116L, E138G, E138R, H221Y, V106L, F116Y, D67N, and V90I were reported to be unknown or to have no effect in the database, but these mutations in selected variants of CRF08_BC showed high to low levels of drug resistance in this study.

Table 3.

Comparison of Drug Resistance Effects Between Reported Mutations Selected in This Study and Those in the HIV Drug Resistance Database of Stanford University

| Level of resistance (increased folds of EC50) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Mutations | In this study | In HIV drug resistance database |

| NVP | V90I | M (4) | L (UD) |

| K101E | M (12) | M (9) | |

| V106I | M (11) | No effect | |

| V106M | H (21) | H (70) | |

| V108I | L (3) | L (UD) | |

| F116L | L (1) | Unknown | |

| E138G | M (6) | No effect | |

| E138R | H (55) | Unknown | |

| Y181C | H (105) | H (123) | |

| Y188C | H (61) | H (216) | |

| G190A | H (69) | H (91) | |

| H221Y | M-H | No effect | |

| EFV | L100I | H (53) | M (10) |

| V106L | H (76) | No effect | |

| F116Y | M (12) | No effect | |

| Y188C | H (51) | L-H (352) | |

| 3TC | D67N | L (3) | Unknown |

| V90I | L (2) | Unknown | |

| M184I | H (1543) | H (200) | |

H, high level of resistance [fold change (FC)>20]; M, medium level of resistance (20>FC>4); L, low level of resistance (FC<4). UD, undetected. They were defined according to the Stanford database http://hivdb.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/Marvel.cgi

Discussion

In the absence of available data about the drug resistance mutations of CRF08_BC in ARV treatment failure patients, we carried out this in vitro RTI selection study on a clinically isolated CRF08_BC virus strain in PBMC cultures and identified the patterns of mutations appearing during the selection cultures, which may most likely also arise in patients treated with NRTIs and NNRTIs. It is also necessary to understand the differences between the emerging CRF and subtype B virus in response to antiretroviral drugs and in drug resistance pathway.

To understand the genetic background of 2007CNGX-HK, the virus genome was sequenced and confirmed to be CRF08_BC (Fig. 1). The RT of CRF08_BC was mainly from subtype C, but amino acids from 102 to 200 in RT containing the polymerase catalytic site and the binding sites of RTIs were recombined from subtype B.3 Although we would not anticipate distinct differences of resistance development in CRF08_BC by comparison with subtype B, different combinations of subtypes in the RT of CRF08_BC may provide genetic resources for potential genotypic and phenotypic drug resistance. It inspired us to explore the drug-resistant mutations in RT of this unique CRF.

In this study, although significant differences between NVP and EFV are not expected, mutation preferences are confirmed to be different between these two NNRTIs after statistical analyses with a large clinical dataset.44 For NRTI, d4T was not recommended for treatment because of mitochondrial toxicity, whereas it was suggested that ddI be replaced by 3TC according to WHO. In fact, we had included AZT in our study, but the virus failed to develop any resistance mutations. Some researchers also reported unsuccessful in vitro selection of AZT-related mutations, but additional studies indicated that cell lines (MT-2 and MT-4), in which viruses replicate efficiently, were important factors for AZT-associated mutation development in vitro.45,46 Therefore, 3TC, rather than PIs and NRTIs, were used in this study.

In this study, the virus strain was isolated in 2007 from a patient who was diagnosed in the same year and was without treatment history. The possibility of selecting the mutations from the preexisting minority resistance population in the reservoir during our in vitro selections is low. We terminated the selection experiment at 22, 30, or 40 passages with 64 μM 3TC, 2 μM EFV, or 128 μM NVP, respectively. This was because (1) the virus titer of resistant variants, cultured in the end point concentration of RTI for about three to five passages, was still less than 20% of the untreated control, so that it would be hard to further scale up the drug concentration; and (2) the RTI concentration was also equal to or higher than the end point of the other in vitro selection studies.47–49 All the mutations listed in Table 1 were not detected in the parental virus or drug-free control in the end of the selection experiment.

According to the HIVdb program, NVP-associated substitutions contained five major NNRTI resistance mutations (K101E, V106A, Y181C, Y188C, and G190A), two secondary NNRTI resistance mutations (V108I and F227L), two NRTI resistance mutations (D67N and N348I), two common polymorphisms (V90I and V106I), one uncommon polymorphism (K101R), and four unusual or rare or uncommon mutations (F116L, E138G/R, and H221Y). K20R, E203K, and D218E were not included in HIVdb but were characterized by analyzing HIV-1 sequences from NRTI-treated and naive patients.36,37 V189I and T369I had been selected as additional mutations in vitro by investigating NNRTIs.50 T139V has been reported to be found in subtype D virus and confers NNRTI resistance.39,51

Surprisingly, seven mutations (V8I, S134N, C162Y, L228I, Y232H, E396G, and E404N) were selected in the escalation of NVP, respectively. The substitutions in the CRF08_BC virus selected by EFV or 3TC were less complicated than those selected by NVP. For NNRTI-EFV-associated variants, two primary NNRTI resistance mutations (L100I and Y188C), one NRTI resistance mutation (F116Y), and one rare polymorphism (V106L) were identified. NNRTIs inhibit HIV-1 replication by binding to the hydrophobic pocket of RT and blocking polymerase activity. It has been indicated that NNRTIs would inhibit viruses in different subtypes of HIV-1 with the same mechanism. For NRTI-3TC-associated mutations, two NRTI mutations (M184I and D67N) and one common polymorphism (V90I) were detected.

Five (Y181C, G190A, H221Y, K101E, and V108I) of the 10 most common mutations identified from NVP-experienced individuals44 were found in this in vitro selection study. Although the other five of the 10 most common NVP mutations identified in HIV patients (K103N, A98G, V106A, E138A, and Y188L) were not found in this study, other mutations at the same position, e.g., V106I, E138G/R, and Y188C, instead of V106A, E138A, and Y188L, were induced in CRF08_BC by NVP selection. V106A had emerged, but it was not persistent through the end of the selection. The number of mutations selected by EFV was less than that induced by NVP.

The second prevalent EFV-related mutation L100I44 was detected in EFV-selected variants of CRF08_BC. The common mutations resistant to EFV (Y188L and V106M) were not found, but the other mutations at the same positions (Y188C and V106L) were induced by in vitro EFV selection. Thus, it is very possible that these mutations may be found in CRF08_BC patients with NVP treatment. Attention should be paid to these mutations in HIV patients on treatment. The most common NNRTI mutation in the clinic, K103N, was not selected in our study and it was difficult to provide an explanation. We also found that several previous studies did not report K103N in their in vitro selection with NVP or EFV.26,48,52,53 Although K103N failed to be selected in our study, this popular mutation should be carefully monitored in patients.

After searching the references in PubMed, there were no reports of clinical data on the effectiveness of first-line ART in Chinese patients infected with CRF08_BC viruses, but potential mutations were detected in treatment-naive patients. NNRTI mutations (E138A/K, V179T/D/K, V106I, P236S/R, and M230V) and NRTI mutations (T69S/D, L210M/F, and A62V) were found in CRF08_BC without treatment history and E138A/K were the most commonly observed NNRTI mutations in volunteer blood donors from Chinese blood centers.7 Mutations on codons 138 and 106 were developed in this study and a serious drug-resistant effect was also detected in E138R and V106L. It is suggested that codon variations in amino acids 138 and 106 were highly related to RTI resistance.

Three distinct NVP resistance mutation profiles initiated by Y181C, E138G, and Y188C and two different EFV-resistant mutation profiles led by L100I and Y188C were observed in CRF08_BC in vitro selection. Y188C was the major EFV-selected mutation and M184I was the dominant mutation selected by 3TC, whereas diverse known resistance mutations (Y181C, Y188C, and G190A) were detected in NVP-selected cultures. In several previous studies of in vitro resistance selections, however, a single mutation such as Y181C was reported to be selected and caused a serious reduction in NVP susceptibility.26,48,53 Mutation L100I was also induced as the first mutation by EFV in subtype B virus in the in vitro study.52

Recently, complicated mutation profiles were observed in a novel NNRTI (ETV) and distinct mutation profiles were detected in non-subtype B virus by EFV and ETV.47,49 Increasing attention was paid to pairwise and higher order patterns of NNRTI-associated mutations because clinically significant resistance to the first- or second-generation NNRTIs was usually related to multiple mutations. Multiple mutations could be detected in about 50% of patients who had developed at least one NNRTI mutation. After analyzing 1,133 and 1,510 isolates of the virus from patients who received only EFV and NVP, respectively, Y181C with seven other mutations and L100I with three other substitutions were found to be covaried significantly. Furthermore, Y181C was often observed in virus variants with three or more NNRTI-selected mutations.46 According to the above-mentioned study, the objective criteria and justification for branching experiments were considered as follows: virus variants would be subcultured in duplicate or quadruplicate when the initial or major NVP-associated mutations (e.g., Y181C) was detected, which may recruit other mutations as clustering variants in the following culture.

To monitor the development of the accessory mutations in mutants from early passages that developed known primary mutations (Y181C, E138G, and Y188C), virus variants were subcultured in duplicate or quadruplicate. The “branching” of experiments created additional room for the development of covariation and clustering mutations with the pressure of NVP. With the increasing concentration of NVP, known major mutations (Y181C and Y188C) and E138G were first detected in parallel cultures. According to a previous study, positively or negatively correlated mutation pairs and clustering mutation development were found in NNRTI-selected mutations, especially for G190A, Y181C, V108I, K101E, H221Y, and F227L.44

It seemed that initial or existing mutations might have some influence on the emergence of the following NVP-related mutations. For example, Y181C was proved to be significantly associated with G190A, H221Y, V108I, A98G, G190S, and V179F by covariation analysis in a dataset with 13,039 sequences isolated from individuals carrying at least one NNRTI mutation.44 This is the first report that complicated mutation profiles were selected by NVP and EFV by in vitro selection, which was partially matched with the covariation phenomenon in clinical studies. In addition, mutations at position 138 (E138G/R), which were considered as rilpivirine (RPV) and ETR resistance, were induced by NVP in this study. It is suggested that NVP-selected mutations at position 138 in CRF08_BC would be cross-resistant to new NNRTIs. Moreover, the latest study reported that E138G/R could interact with M184I to decrease RPV and ETR susceptibility and compensate for RT enzymatic fitness and viral replication capacity.54 Considering the selections of E138G/R and M184I in this study, we should pay close attention when patients with CRF08_BC are receiving NVP/3TC-containing therapy.

We also compared the resistance patterns between our results and the Stanford University HIV drug resistance database. Most of the resistance patterns with major mutations found in this study were covered in the database-reported clinical patterns. This indicated that it may be possible to find these patterns in patients carrying CRF08_BC. For non-database-reported mutation patterns that were observed in our study, for example, E138G or E138R or V106L-containing profiles, they were also important because a new pattern development may be influenced by new genetic resources from difference subtype recombinations.

In this study, susceptibility assays were performed to determine the phenotypic effect of different mutations in CRF08_BC (Fig. 3). We found that initial mutations Y181C, Y188C, L100I, Y188C, and M184I selected, respectively, by NVP, EFV, and 3TC could cause over 20-fold drug resistance. These initial mutations should be carefully monitored in clinical studies. It was the first report that E138G/R selected by NVP and E138R strongly reduced CRF08_BC virus susceptibility to NVP. E138G/R was recognized as a mild mutation of the second generation NNRTI ETR and RVP in in vitro selection or in patients with treatment failure.49 It is possible that E138G/R may develop in CRF08_BC in NVP treatment and these mutations may cause 2- to 3-fold cross-resistance to the next generation of NNRTIs.54

Mutation V106L was induced by EFV selection cultures and displays over 50-fold resistance to EFV. The mutation at position 106 may severely decrease NNRTI sensitivity (V106A/M) or just be a common polymorphism (V106I). No report has shown that V106L confers resistance to NNRTIs, although one study indicated that V106L in combination with multiple mutations would be extremely resistant to novel NNRTIs but not to current commercial NNRTIs.41 A139V was observed with a gradual increase of NVP and EFV. A139V alone resulted in less susceptibility to EFV at a medium level, but caused high level resistance to NVP together with a novel mutation Y232H. A139V was not characterized as a resistant mutation in the Stanford University HIV drug resistance database.

Only one report indicated that 139V may be related to NNRTI resistance in subtype D.39 With the increase of subtypes and CRFs of HIV and antiretroviral drugs, it is possible that an increasing number of new drug resistance mutations and new resistance pathways will be found in non-B-infected patients. Seven novel mutations were found in CRF08_BC. The novel mutations alone, or together with other mutations, have shown different phenotypic effects on NVP.

In the study by Iglesias-Ussel et al., subtype B virus was used for the generation of NVP-resistant variants with a 2-fold escalation of drug concentration in serial passages.48 The selection strategy was the same as that in our study. Mutations V106A, Y181C, and G190A were observed and Y181C caused a 100-fold decrease in NVP susceptibility, while double mutations (Y181C/G190A and Y181C/V106A) were associated with a 500-fold decrease in sensitivity to NVP. These three mutations were also detected in CRF08_BC. Furthermore, Y181C showed a 105-fold phenotypic resistance effect in CRF08_BC, which was similar to the effect in subtype B. Since G190A in CRF08_BC decreased the effect of NVP 69-fold, Y181C in combination with G190A may be expected to cause serious resistance (over 500-fold) to NVP similar to that found in subtype B. In the other two previous cell culture studies, the subtype B virus was adopted for resistant variants selection in fixed drug concentrations (1 μM and 10 μM NVP) and a mutant carrying Y181C was detected and also associated with a 100-fold decrease in susceptibility in both articles.26,53

In the study by Lai et al., subtype B and C viruses were used to investigate mutation pathways with 2- to 5-fold increasing pressure of EFV in continuing passages. Multiple mutations and diverse pathways (L100I/N348I, V179D/L100I/V108I, and K103N/Y188C) developed in subtype B viruses, whereas G190A/V106M was the single pathway for the subtype C virus.47 By comparing the results with this study, the overlay EFV-related mutations in both subtype B and CRF08_BC were L100I and Y188C; no similar mutations were found between subtype C and CRF08_BC. Because of similar previous studies and the heavy workload in our study, we did not employ a control culture with the subtype B isolate employing the same conditions we used with CRF08_BC. This might be a weak point in this study because we could not observe the direct differences in mutation patterns between CRF08_BC and subtype B.

At present, HIV monotherapy would be considered to be obsolete; hence the applicability of results from single drug passage experiments to the clinical choice or sequencing of antiretrovirals in different patient populations remains unclear. In addition, the opportunity to investigate possible antagonistic or synergistic effects of NRTI–NNRTI combinations was not available in single drug passage experiments. The ability to use single but not cocktail drugs to do the experiment was another limitation in our study. Since 3TC in combination with NVP or EFV was adopted in treatment for several years, we did not investigate their possible antagonistic or synergistic effects in this study.

Without available treatment failure-generated mutations in CRF08_BC, the findings in this study may provide some clinical suggestions for the management of patients. If CRF08_BC is identified in a patient, NVP resistance should be carefully monitored because NVP-induced mutation profiles and the mutations seriously reduce NVP susceptibility as shown in our study. Furthermore, E138R/G, the second-generation NNRTI-related mutation, was identified under NVP pressure and may cause cross-resistance to RPV and ETR. Cross-resistance would impose restrictions on the choice of NNRTIs because the effect of RPV and ETR may be reduced after NVP treatment failure or resistance to RPV and ETR may increase due to the NVP mutations. All the resistance mutations identified in this in vitro selection should be screened before the selection of antiretroviral drugs and closely monitored even though in treatment nonfailure patients who avoided complicated multiple mutation profiles appeared.

In conclusion, our study has revealed that the evolution of a clinically isolated CRF08_BC virus strain resistant to NVP, EFV, and 3TC can be induced in selection cultures in vitro. Our results suggested the possibility that initial mutations Y181C, Y188C, E138G, L100I, and M184I might be found in patients harboring the CRF08_BC virus when NVP, EFV, or 3TC was included in the ART regimen and these mutations might cause high levels of resistance to the antiretroviral drugs. The mutation profiles and the drug resistance level in this study were comparable and partially consistent with those reported in other subtypes in both in vitro culture and clinical patient pools.

Furthermore, the mutations of E138G/R, V106L, and A139V were first reported to cause resistance to NVP or EFV and E138G/R will be cross-resistant to a new generation NNRTI. Seven novel mutations have been selected by the cultures in the presence of NVP in diverse and variable combinations with the other major mutations in our study. This phenomenon may happen when a rising number of patients infected with different HIV CRFs come into therapy. These results may provide insight into the development of drug-related mutations in patients and provide useful information in adopting the ideal antiretroviral regimens to control CRF08_BC in the future.

Sequence Data

The GenBank accession number for the viral sequence of virus strain 2007CNGX-HK in this work is KF312642.

Acknowledgments

We are highly appreciative of the resources made available by the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH; these include TZM-bl from Drs. John C. Kappes, Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme Inc. This work was supported in part by AIDS Trust Fund, Government of Hong Kong SAR.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Tebit DM, Nankya I, Arts EJ, and Gao Y: HIV diversity, recombination and disease progression: How does fitness “fit” into the puzzle? AIDS Rev 2007;9(2):75–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teng T. and Shao Y: Scientific approaches to AIDS prevention and control in China. Adv Dent Res 2011;23(1):10–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piyasirisilp S, McCutchan FE, Carr JK, et al. : A recent outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in southern China was initiated by two highly homogeneous, geographically separated strains, circulating recombinant form AE and a novel BC recombinant. J Virol 2000;74(23):11286–11295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takebe Y, Liao H, Hase S, et al. : Reconstructing the epidemic history of HIV-1 circulating recombinant forms CRF07_BC and CRF08_BC in East Asia: The relevance of genetic diversity and phylodynamics for vaccine strategies. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 2):B39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallego O, d'Mendoza C, Labarga P, et al. : Long-term outcome of HIV-infected patients with multinucleoside-resistant genotypes. HIV Clin Trials 2003;4(6):372–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Sun G, Liang S, et al. : Different distributions of HIV-1 subtype and drug resistance were found among treatment naive individuals in Henan, Guangxi, and Yunnan province of China. PLoS One 2013;8(10):e75777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng P, Wang J, Huang Y, et al. : The human immunodeficiency virus-1 genotype diversity and drug resistance mutations profile of volunteer blood donors from Chinese blood centers. Transfusion 2012;52(5):1041–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menendez-Arias L: Molecular basis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance: Overview and recent developments. Antiviral Res 2013;98(1):93–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T, Dai Y, Kuang J, et al. : Three generic nevirapine-based antiretroviral treatments in Chinese HIV/AIDS patients: Multicentric observation cohort. PLoS One 2008;3(12):e3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo L. and Li TS: Overview of antiretroviral treatment in China: Advancement and challenges. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124(3):440–444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barth RE, van der Loeff MF, Schuurman R, et al. : Virological follow-up of adult patients in antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10(3):155–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Cajas JL, Pant-Pai N, Klein MB, and Wainberg MA: Role of genetic diversity amongst HIV-1 non-B subtypes in drug resistance: A systematic review of virologic and biochemical evidence. AIDS Rev 2008;10(4):212–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Geng Q, Guo W, et al. : Screening for and verification of novel mutations associated with drug resistance in the HIV type 1 subtype B(') in China. PLoS One 2012;7(11):e47119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Zhong M, Guo W, et al. : Prevalence and mutation patterns of HIV drug resistance from 2010 to 2011 among ART-failure individuals in the Yunnan Province, China. PLoS One 2013;8(8):e72630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu G, Li Y, Li J, et al. : Genetic diversity and drug resistance of HIV type 1 circulating recombinant form_BC among drug users in Guangdong Province. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2009;25(9):869–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Zhang X, Wu H, et al. : Parental LTRs are important in a construct of a stable and efficient replication-competent infectious molecular clone of HIV-1 CRF08_BC. PLoS One 2012;7(2):e31233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu H, Zhang HJ, Zhang XM, et al. : Identification of drug resistant mutations in HIV-1 CRF07_BC variants selected by nevirapine in vitro. PLoS One 2012;7(9):e44333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, et al. : An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics 2005;21(19):3797–3800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michael N. and Kim JH: HIV Protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vergne L, Peeters M, Mpoudi-Ngole E, et al. : Genetic diversity of protease and reverse transcriptase sequences in non-subtype-B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains: Evidence of many minor drug resistance mutations in treatment-naive patients. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38(11):3919–3925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vergne L, Stuyver L, Van Houtte M, et al. : Natural polymorphism in protease and reverse transcriptase genes and in vitro antiretroviral drug susceptibilities of non-B HIV-1 strains from treatment-naive patients. J Clin Virol 2006;36(1):43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staden R, Beal KF, and Bonfield JK: The Staden package, 1998. Methods Mol Biol 2000;132:115–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JH, Wong KH, Chan K, et al. : Evaluation of an in-house genotyping resistance test for HIV-1 drug resistance interpretation and genotyping. J Clin Virol 2007;39(2):125–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu TF. and Shafer RW: Web resources for HIV type 1 genotypic-resistance test interpretation. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42(11):1608–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi Y, McClure MO, and Pizzato M: Identification of gammaretroviruses constitutively released from cell lines used for human immunodeficiency virus research. J Virol 2008;82(24):12585–12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richman D, Shih CK, Lowy I, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants resistant to nonnucleoside inhibitors of reverse transcriptase arise in tissue culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991;88(24):11241–11245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelemans H, Aertsen A, Van Laethem K, et al. : Site-directed mutagenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase at amino acid position 138. Virology 2001;280(1):97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richman DD: Resistance of clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus to antiretroviral agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993;37(6):1207–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrnes VW, Sardana VV, Schleif WA, et al. : Comprehensive mutant enzyme and viral variant assessment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase resistance to nonnucleoside inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993;37(8):1576–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bacolla A, Shih CK, Rose JM, et al. : Amino acid substitutions in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with corresponding residues from HIV-2. Effect on kinetic constants and inhibition by non-nucleoside analogs. J Biol Chem 1993;268(22):16571–16577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larder BA: 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine resistance suppressed by a mutation conferring human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992;36(12):2664–2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleim JP, Winkler I, Rosner M, et al. : In vitro selection for different mutational patterns in the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase using high and low selective pressure of the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor HBY 097. Virology 1997;231(1):112–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yap SH, Sheen CW, Fahey J, et al. : N348I in the connection domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase confers zidovudine and nevirapine resistance. PLoS Med 2007;4(12):e335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato A, Hammond J, Alexander TN, et al. : In vitro selection of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase that confer resistance to capravirine, a novel nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Antiviral Res 2006;70(2):66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azijn H, Tirry I, Vingerhoets J, et al. : TMC278, a next-generation nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), active against wild-type and NNRTI-resistant HIV-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54(2):718–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saracino A, Monno L, Scudeller L, et al. : Impact of unreported HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutations on phenotypic resistance to nucleoside and non-nucleoside inhibitors. J Med Virol 2006;78(1):9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svicher V, Sing T, Santoro MM, et al. : Involvement of novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase mutations in the regulation of resistance to nucleoside inhibitors. J Virol 2006;80(14):7186–7198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta S, Fransen S, Paxinos EE, et al. : Combinations of mutations in the connection domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase: Assessing the impact on nucleoside and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54(5):1973–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao Y, Paxinos E, Galovich J, et al. : Characterization of a subtype D human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate that was obtained from an untreated individual and that is highly resistant to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J Virol 2004;78(10):5390–5401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mellors JW, Im GJ, Tramontano E, et al. : A single conservative amino acid substitution in the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus-1 confers resistance to (+)-(5S)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-5-methyl-6-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)imidazo[4,5, 1- jk][1,4]benzodiazepin-2(1H)-thione (TIBO R82150). Mol Pharmacol 1993;43(1):11–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kodama E, Orita M, Masuda N, et al. : Binding modes of two novel non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, YM-215389 and YM-228855, to HIV type-1 reverse transcriptase. Antiviral Chem Chemother 2008;19(3):133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirasaka T, Kavlick MF, Ueno T, et al. : Emergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with resistance to multiple dideoxynucleosides in patients receiving therapy with dideoxynucleosides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92(6):2398–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MARVEL (Mutation ARV Evidence Listing): Stanford University HIV drug resistance database. Available at http://hivdb.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/Marvel.cgi

- 44.Reuman EC, Rhee SY, Holmes SP, and Shafer RW: Constrained patterns of covariation and clustering of HIV-1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutations. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(7):1477–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larder BA, Coates KE, and Kemp SD: Zidovudine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus selected by passage in cell culture. J Virol 1991;65(10):5232–5236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Q, Gu ZX, Parniak MA, et al. : In vitro selection of variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistant to 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine and 2',3'-dideoxyinosine. J Virol 1992;66(1):12–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai MT, Lu M, Felock PJ, et al. : Distinct mutation pathways of non-subtype B HIV-1 during in vitro resistance selection with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54(11):4812–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iglesias-Ussel MD, Casado C, Yuste E, et al. : In vitro analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to nevirapine and fitness determination of resistant variants. J Gen Virol 2002;83(Pt 1):93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vingerhoets J, Azijn H, Fransen E, et al. : TMC125 displays a high genetic barrier to the development of resistance: Evidence from in vitro selection experiments. J Virol 2005;79(20):12773–12782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleim JP, Rosner M, Winkler I, et al. : Selective pressure of a quinoxaline nonnucleoside inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) on HIV-1 replication results in the emergence of nucleoside RT-inhibitor-specific (RT Leu-74→Val or Ile and Val-75→Leu or Ile) HIV-1 mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93(1):34–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Z, Xu W, Koh YH, et al. : A novel nonnucleoside analogue that inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates resistant to current nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51(2):429–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winslow DL, Garber S, Reid C, et al. : Selection conditions affect the evolution of specific mutations in the reverse transcriptase gene associated with resistance to DMP 266. AIDS 1996;10(11):1205–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mellors JW, Dutschman GE, Im GJ, et al. : In vitro selection and molecular characterization of human immunodeficiency virus-1 resistant to non-nucleoside inhibitors of reverse transcriptase. Mol Pharmacol 1992;41(3):446–451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu HT, Colby-Germinario SP, Asahchop EL, et al. : Effect of mutations at position E138 in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and their interactions with the m184i mutation on defining patterns of resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors rilpivirine and etravirine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57(7):3100–3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]