Abstract

Asymmetric division of stem cells is a highly conserved and tightly regulated process by which a single stem cell produces two daughter cells and simultaneously directs the differential fate of both: one retains its stem cell identity while the other becomes specialized and loses stem cell properties. Coordinating these events requires control over numerous intra- and extracellular biological processes and signaling networks. In the initial stages, critical events include the compartmentalization of fate determining proteins within the mother cell and their subsequent passage to the appropriate daughter cell. Disturbance of these events results in an altered dynamic of self-renewing and differentiation within the cell population, which is highly relevant to the growth and progression of cancer. Other critical events include proper asymmetric spindle assembly, extrinsic regulation through micro-environmental cues, and noncanonical signaling networks that impact cell division and fate determination. In this review, we discuss mechanisms that maintain the delicate balance of asymmetric cell division in normal tissues and describe the current understanding how some of these mechanisms are deregulated in cancer.

The universe is asymmetric and I am persuaded that life, as it is known to us, is a direct result of the asymmetry of the universe or of its indirect consequences. The universe is asymmetric.

–Louis Pasteur

Introduction

Stem cells are a small and specialized population that occupies specific biological niches of developing and mature organisms. One capacity critical to their identity and proper function is the ability to replicate in a manner that maintains stemness, yet also generates daughter cells that are capable of multilineage differentiation. This complex process of asymmetric cell division allows a singular mother cell to give rise to daughter cells distinct in size, shape, function, and fate. The creation of two progeny with such differing destinies requires a tightly regulated molecular program. As a rule, disturbances in asymmetric cell division lead to the creation of two daughter cells that retain stemness, have diminished capacity to fully differentiate [1,2]. Disrupted stem cell/progeny dynamics lead to abnormal tissue growth properties, with relevance to cancer quickly being recognized.

Since the description of asymmetric cell division by Conklin over a century ago, mechanistic detail has been slow to arrive [3]. Current understanding has relied on a limited number of sources, with Drosophila being the prime model used to study division properties of neuroblasts, germline stem cells, and intestinal stem cells [1]. In mammalian systems, most advances have been made through the study of mouse radial glial progenitors [4], neocortical progenitors [5], and muscle satellite cells [6]. The more recent recognition of a stem cell population in cancer has led to investigations of asymmetric cell division in this disease, using mammalian systems and Drosophila as models. Here, we review the current understanding of asymmetric cell division as it occurs normally and discuss how its disruption is related to the development and progression of cancer, highlighting the role of cancer stem cells in this process.

Mechanisms of Asymmetric Cell Division

Mechanisms regulating asymmetric cell division have been explored in model systems ranging from Caenorhabditis elegans to mammals, yet investigations of Drosophila have dominated [1]. Achievement of asymmetric fate following cell division depends on multiple critical processes: (i) correct localization and function of fate-determining protein complexes at apical and basal aspects; and (ii) proper asymmetric spindle assembly and function; (iii) extrinsic regulation within the stem cell niche; and (iv) influences from noncanonical signaling pathways [7]. This process begins at interphase and ends with cytokinesis.

Regulation of Asymmetry Through Localization of Fate Determinants

Drosophila neuroblasts in the developmental stages have been a prime source of understanding intrinsic regulators of asymmetric cell division. In this model, division is initiated by apical localization of a protein complex—together known as apical determinants—that includes atypical protein kinase C (aPKC), partition defective 6 (PAR6), and lethal giant larvae [L(2)GL]. A second complex including Miranda, Brat, and Prospero, localizes to the basal aspect and are known as basal determinants. Differential segregation of these fate-mapping protein complexes eventually provides distinct identities to daughter cells containing them. How the cell determines which protein complex should move apically versus basally remains a mystery.

Apical determinants

Normal conditions

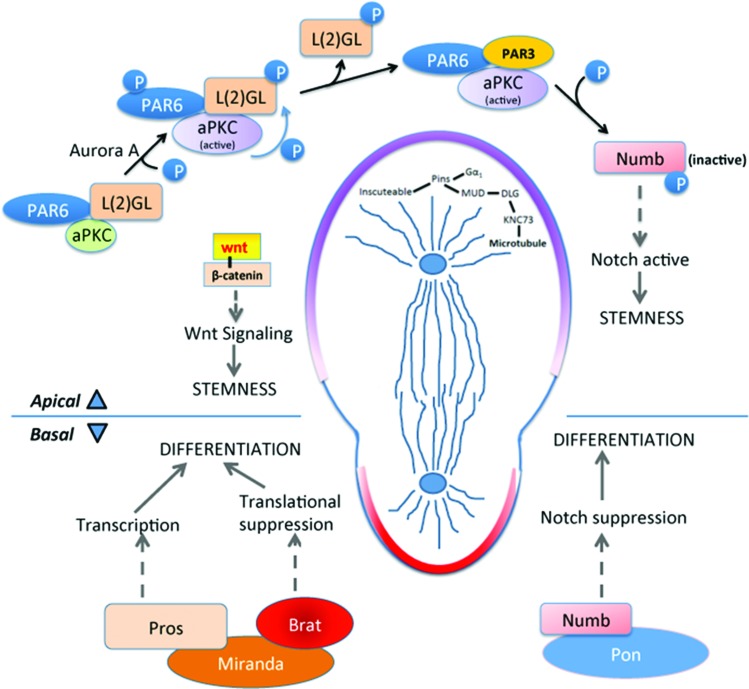

During normal interphase, aPKC localizes apically upon forming a complex with PAR6 and L(2)GL (Fig. 1). Aurora A, a serine-threonine protein kinase initiates apical signaling by phosphorylating PAR6, which in turn activates aPKC [1]. Activated aPKC phosphorylates L(2)GL, reducing its affinity with the complex and leading to its replacement by PAR3 [1]. Under normal conditions, activation of L(2)GL and the entry of PAR3 leads to the critical event of Numb phosphorylation, inactivating and releasing it from the apical plasma membrane (Fig. 1). Numb is a well-established Notch signaling suppressor, and its inactivation therefore upregulates Notch signaling, providing self-renewal properties to the apical daughter [1].

FIG. 1.

During asymmetric cell division, two distinct molecular programs take place on the apical and basal pole. Apical pole: At the apical side, aPKC/PAR6/PAR3 complex formation initiates during interphase, giving apical pole the identity of self-renewal. Aurora A protein kinase phosphorylates aPKC leading to its activation. Active aPKC phosphorylates L(2)GL which releases L(2)GL from the complex and PAR3 enters. This complex phosphorylates Numb releasing it from the apical membrane and increasing Numb concentration at the basal side. This keeps the Notch signal active on the apical side causing stemness. Wnt signal also takes part in the self-renewal, though the detailed mechanism is not known. In metaphase and telophase, apical microtubule arrangement is maintained by Inscuteable/Pins/Gαi complex. Cytoskeletal adapter protein binds with Pins and Gαi whereas Mud forms a complex with Dlg and Knc73. These two complexes come together that arranges the microtubules attached to Knc73. Basal pole: Adapter protein Miranda on the basal pole binds with Prospero and Brat. Degradation of Miranda releases transcription factor Prospero that turns on the genes driving differentiation. Brat on the other hand, acts as a translational repressor, possibly suppressing protein production needed for proliferation. brat ortholog TRIM32 also transports cMYC to endosomes for its degradation. Higher accumulation of NUMB on the basal membrane leads to the degradation of NOTCH1 inside endosomes. This suppresses Notch signal and its proliferative effect on the basal side. aPKC, atypical protein kinase C. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Results concordant with Drosophila have been established using mammalian systems: during asymmetric cell division of radial glia within the mouse brain ventricular zone, the aPKC/PAR6/PAR3 complex accumulates at the apical side [1] with the help of a small GTP-binding protein, CDC42 [1]. This complex ensures apical adherens junction integrity and establishes apico-basal polarity [8].

In neoplasia

In neoplastic disease, disruption of signaling networks involved in asymmetric division typically gives rise to a proliferative state and accumulation of stem-like cells with limited capacity to differentiate. For example, a mutant form of Drosophila aPKC that is constitutively active initiates Notch signaling through reduction of active Numb on apical and basal sides, thereby promoting neuroblast self-renewal and tumor formation [1,9]. In contrast, suppression of aPKC results in reduced numbers of neuroblasts, establishing aPKC as a protumorigenic protein. Similarly, Aurora A mutants generate tumors by enhanced Notch signaling [7]. L(2)GL mutants also display a neoplastic proliferation of stem-like cells [10], likely through the formation of a nonfunctional aPKC/PAR6/PAR3 complex and activation of Notch on both apical and basal sides.

In mammalian systems, disruption of apical determinants has similar effects. Overexpression of PAR3 drives radial glial cells toward symmetric division and retention of stem-like properties of both daughter cells [5] by keeping Numb inactive, thereby enhancing Notch signaling [11]. PAR6 has been established as a causal factor for breast cancer epithelial–messenchymal transition (EMT) through transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling. Mutated PAR6 attenuates TGF-β signaling in mice and suppresses lung metastasis of mammary tumors [12]. Loss of LGL1, a mammalian ortholog of fly L(2)GL, disrupts neural progenitor cell differentiation in the ventricular region of the mouse cerebellum, and promotes proliferation [13].

There are numerous examples of human cancers that harbor alterations in orthologs of Drosophila genes related to asymmetric cell division. For example, deletions in PARD6 (PAR6), PARD3 (PAR3), and DLG2 are prevalent in human epithelial neoplasms. PARD6 deletion disrupts the cell polarity causing neoplastic growths in lung and adrenal cancer (Table 1). PARD3 deletion in squamous cell carcinomas and glioblastomas leads to the loss of cell polarity, symmetric cell division, and enhanced proliferation. DLG2 is most frequently deleted in cervical and lung cancer, and generates a phenotype similar to PARD3 deletion [14,15]. AURKB, the human ortholog of Aurora kinase is frequently deleted in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma, strongly supporting a connection between neoplastic disease and deregulation of symmetric cell division (Table 1). In some human cancer types, genes implicated in asymmetric cell division have been shown to alter properties of cancer stem cells [1,16], while in other instances this has not been demonstrated.

Table 1.

Mutations and Copy Number Variations of Genes Relevant to Asymmetric Cell Division in Human Cancers

| Cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | Genes abbreviations | Chromosomal location | Deletion (%) | Gain (%) | Mutation (%) |

| Aurora kinase B | AURKB | 17p13.1 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (76.69%) | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (58.88%) | Small cell lung cancer (CLCGP, Nature Genetics 2012) [60] (3.4%) |

| Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (75.76%) | Sarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (24.67%) | Prostate adenocarcinoma (Broad/Cornell, Cell 2013) [61] (1.8%) | |||

| Cyclin D1 | CCND1 | 11q13 | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (39.29%) | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (45.42%) | Uterine corpus endometrioid carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2013) [62] (6.3%) |

| Skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA, Provisional) (29.17%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (42.54%) | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (Genentech, Nature 2012) [64] (4.2%) | |||

| Cyclin E1 | CCNE1 | 19q12 | Brain lower grade glioma (TCGA, Provisional) (32.71%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (78.57%) | Small cell lung cancer (CLCGP, Nature Genetics 2012) [60] (3.4%) |

| NCI-60 cell lines (NCI, Cancer Res. 2012) [65] (26.67%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (62.22%) | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (Genentech, Nature 2012) [64] (2.8%) | |||

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | CDK4 | 12q14 | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (21.43%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (77.78%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Broad, Cell 2012) [66] (5%) |

| Skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA, Provisional) (18.15%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (37.01%) | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2%) | |||

| Beta-catenin | CTNNB1 | 3p21 | Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (92.43%) | Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2014) [67] (35.94%) | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (29.6%) |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (73.86%) | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (26.90%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (15.7%) | |||

| Disc large 1 | DLG1 | 3q29 | Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (29.57%) | Lung squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2012) [68] (80.34%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Yale, Nature Genetics 2012) [69] (4.4%) |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (22.22%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (72.39%) | Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (3.8%) | |||

| Epidermal growth factor receptor | EGFR | 7p12 | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (16.07%) | Glioblastoma multiforme (TCGA, Provisional) (89.13%) | Lung adenocarcinoma (TSP, Nature 2008) [70] (18.4%) |

| Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (15.99%) | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (60.41%) | Stomach adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (5%) | |||

| G-protein signaling modulator 1 | GPSM2 | 1p13.3 | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (80.30%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (35.71%) | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2.9%) |

| Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (32.61%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (30.27%) | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (Genentech, Nature 2012) [64] (2.8%) | |||

| Lethal giant larvae 2 | LLGL2 | 17q25.1 | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (72.73%) | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (72.08%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Broad, Cell 2012) [66] (5.8%) |

| Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (36.73%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (53.57%) | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (Genentech, Nature 2012) [64] (5.6%) | |||

| MicroRNA 146A | MIR146A | 5q34 | Lung squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2012) [68] (50.56%) | Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (65.60%) | NA |

| Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (46.61%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (65.56%) | NA | |||

| MicroRNA 34A | MIR34A | 1p36.22 | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (80.30%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (33.93%) | NA |

| Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (44.22%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (32.16%) | NA | |||

| MicroRNA LET7E | MIRLET7E | 19q13.41 | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (49.08%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (62.22%) | NA |

| Brain lower grade glioma (TCGA, Provisional) (48.12%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (50.00%) | NA | |||

| v-Myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog | MYC | 8q24.21 | Sarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (15.33%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (79.26%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (3.6%) |

| Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (13.64%) | Stomach adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (66.89%) | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2.9%) | |||

| Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 | NUMA1 | 11q13 | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (39.29%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (42.74%) | Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (7.7%) |

| Skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA, Provisional) (29.46%) | Cancer cell line encyclopedia (Novartis/Broad, Nature 2012) [71] (33.67%) | Uterine corpus endometrioid carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2013) [62] (7.1%) | |||

| Numb | NUMB | 14q24.3 | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) (50.31%) | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (31.82%) | Adenoid cystic carcinoma (MSKCC, Nature Genetics 2013) [72] (3.3%) |

| Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (50.00%) | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (30.72%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Broad, Cell 2012) [66] (1.5%) | |||

| Par-3 family cell polarity regulator beta | PARD3B | 10p11.21 | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (72.73%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (39.29%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Yale, Nature Genetics, 2012) [73] (9.9%) |

| Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (38.46%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (35.85%) | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (TCGA Provisional) (6.7%) | |||

| Par-6 family cell polarity regulator alpha | PARD6A | 16q22.1 | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) (79.75%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (62.22%) | Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (3.8%) |

| Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (66.07%) | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (52.28%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Broad, Cell 2012) [66] (3.3%) | |||

| POU class 5 homeobox 1 | POU5F1 | 6p21.31 | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (77.27%) | Uterine carcinosarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (60.71%) | Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (3.8%) |

| Sarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (27.33%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA, Provisional) (49.40%) | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2.8%) | |||

| Protein kinase C, iota | PRKCI | 3q26.3 | Sarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (22.67%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (85.69%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (Broad, Cell 2012) [66] (5%) |

| Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (20.87%) | Lung squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2012) [68] (83.71%) | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2.4%) | |||

| Prospero homeobox 1 | PROX1 | 1q41 | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (77.27%) | Breast invasive carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (73.57%) | Skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA, Provisional) (6.1%) |

| Sarcoma (TCGA, Provisional) (28.67%) | Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (69.13%) | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (5.6%) | |||

| SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 2 | SOX2 | 3q26.3-q27 | Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (28.26%) | Lung squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2012) [68] (84.83%) | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2.8%) |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (21.11%) | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) (79.55%) | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (2%) | |||

| Tripartite motif-containing protein 3 | TRIM3 | 11p15.5 | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (56.59%) | Kidney chromophobe (TCGA, Provisional) (21.21%) | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (4.2%) |

| Bladder urothelial carcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2014) [67] (54.69%) | Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (15.65%) | Small cell lung cancer (CLCGP, Nature Genetics 2012) [60] (3.4%) | |||

| Tripartite motif-containing protein 32 | TRIM32 | 19q33.1 | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (TCGA, Nature 2011) [63] (54.19%) | Adrenocortical carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (37.78%) | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (Genentech, Nature 2012) [64] (6.9%) |

| Skin cutaneous melanoma (TCGA, Provisional) (48.81%) | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (34.97%) | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (TCGA, Provisional) (5.4%) | |||

The listed genes have been identified as potential regulators of asymmetric cell division in cancer. The table shows CNA and mutation rates for each gene uncovered from BioPortal for Cancer Genomics developed by the Computational Biology Center at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (www.cbioportal.org/public-portal/; access on August 06, 2014). Of all 69 cancer study data sets, we identified 48 studies that provide GISTIC [65] results, with −1 and −2 representing hemizygous and homozygous deletion, respectively, and +1 and +2 representing gains. GISTIC results were downloaded through web APIs invoked in MATLAB. We computed the percentage of gains and deletions events and report the two most frequently altered genes for each cancer of interest [66–79].

CNA, Copy Number Alteration; GISTIC, Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer.

Basal determinants

Normal conditions

On the basal side during asymmetric division, the combination of apical Numb phosphorylation and the absence of aPKC/L(2)GL/PAR3 complex leads to accumulation of active Numb, which inhibits Notch signaling and directs this daughter toward differentiation. In addition to active Numb, a highly coil-coiled adapter protein, Miranda, localizes basally during interphase and binds Prospero, a transcription factor, and brain tumor (Brat), a translational repressor [7]. Eventually, Miranda is degraded, releasing Prospero and initiating a transcriptional program that promotes differentiation [7]. Besides being a translational repressor, Brat also attenuates self-renewing Wnt signaling in neuroblasts through β-catenin/Armadillo inhibition [17].

Uncovering precise functions of Brat has been challenging due to its complex structure and reports of numerous, seemingly unrelated functions [18]. Nevertheless, Brat has been firmly established as a driver of differentiation in neuroblasts (Fig. 1). One of the first roles described for Brat was as a translational repressor of Hunchback in the embryo [19], yet deeper mechanistic detail have not emerged. Based on sequence homology and similar protein domains, the mammalian ortholog of Brat belongs within the tripartite motif containing protein family called TRIM. TRIM32, a ubiquitin ligase, has been reported to drive neurogenesis in a mouse model [1] and has several functions that include activation of microRNAs (mi-RNAs), such as Let-7, and binding of c-MYC to promote its degradation [1].

Similar to Drosophila, studies of the mammalian ortholog of Prospero, PROX1, has established its role in supporting neurogenesis in mouse models [20].

In neoplasia

Numb localization on the basal side is critical, since it attenuates Notch signaling (Fig. 1) driving differentiation. As apical fate determinant proteins, such as aPKC and L(2)GL, primarily regulate Numb activation, Numb localization at the basal side depends on them. Under conditions where aPKC is inhibited, phosphorylation of L(2)GL does not occur [1] on the apical side, resulting in attenuated Numb phosphorylation and its failure to localize to the basal membrane [1]. Thus, Numb's aberrant maintenance causes inappropriate Notch signaling after division [21] resulting in excessive proliferation of neuroblasts and tumor growth.

Mutations in miranda, prospero, or brat lead to a brain tumor phenotype in Drosophila, characterized by massively enlarged brains containing neuroblasts that fail to differentiate. These mutants have remarkable similarity, pointing to the common regulatory mechanism shared by these proteins. Transplantation of mutant neuroblasts into the abdomen of wild-type Drosophila results in tumor growth that is ultimately fatal, suggesting they are more that benign or self-limited proliferations [22–24]. Transplanted cells also show metastatic behavior, with primary abdominal neuroblasts forming secondary tumors disseminating far from the primary tumor site [7].

Mutations of mammalian PROX1, the ortholog of Prospero have been noted in pancreatic, esophageal, and colon cancer. Mice xenograft experiments with pancreatic cancer cells show reduced proliferation and self-renewal with the introduction of PROX1 protein [25].

PROX1 alterations and reduced expression are seen in several forms of human neoplasia (Table 1), including hematologic malignancies, where DNA methylation of PROX1 is predominant (56.3%) and contributes to the neoplastic behavior [26]. In hepatocellular malignancies, PROX1 transcription is altered in a manner that promotes progression, while in breast cancer, epigenetic silencing has been described [27,28]. NUMB gene mutation and deletion are hallmark of many cancer types, such as uterine endometrial carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma, where mutation induces self-renewal through Notch activation (Table 1). NUMB protein is reduced in selective subsets of breast cancer [8].

Orthologs of Brat in human cancer have also received increasing attention, especially as related to brain tumors. Among TRIM genes, TRIM3 has greatest sequence homology to Drosophila brat. TRIM3 is also exclusively expressed in the brain, similar to brat in Drosophila. TRIM3 is deleted in about 25% of human glioblastomas and has a similar deletion frequency in lower grade gliomas, suggesting it is an early event in gliomagenesis [29]. Recent studies suggest that TRIM3 also has E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and is a tumor suppressor at least partially through ubiquitination and degradation of p21. However, TRIM3 overexpression suppresses proliferation in oligodendrogliomas in both presence and absence of p21, suggesting other signaling pathways are also impacted [30]. Recent work has corroborated that ∼25% of GBMs have at least one TRIM3 allele deleted and also suggested that nondeleted gliomas have methylated TRIM3 that could account for its lower gene and protein expression in nearly all GBMs [16]. Low TRIM3 protein expression in GBM neurospheres was associated with upregulated Notch signaling, possibly through reduced expression of the negative regulator NUMB. Reconstitution of TRIM3 in TRIM3 null neurospheres led to increased NUMB levels and suppressed Notch signaling. In both glioma cell lines and neuropsheres, the lack of TRIM3 was also tightly coupled with elevated expression and activity of c-MYC. Functional studies showed that TRIM3 expression within a glioma stem cell population (as defined by PKH-26 high) led to reduced symmetric cell division and rescued the asymmetric cell division phenotype. Altogether, these data suggest that the Brat mammalian ortholog TRIM3 regulates cell proliferation and self-renewal signaling within a glioma stem cell population [16].

Another Brat ortholog is TRIM32, which has been shown to ubiquitinate MYC protein, thereby attenuating self-renewal during asymmetric cell division in mice and inhibiting over proliferation and tumor formation [31].

Asymmetric Spindle Assembly

Apical spindle orientation

Normal conditions

During mitotic spindle formation in metaphase and telophase, in preparation for asymmetric cell division, microtubules are arranged in a manner to support division into unequal daughters. The process starts with apical localization of the cytoskeletal adapter protein Inscuteable [32], which then binds with partner of inscuteable (Pins), and the G protein receptor substrate Gαi, in a receptor-independent manner [1]. Also on the apical side, microtubule-bound kinesin Khc73 binds with disc large (Dlg) and forms a complex with Gαi, Pins, and Mud [1]. Altogether, this large protein complex is linked to the apical cytoskeleton through Inscuteable and establishes the correct spindle alignment and the orthogonal cleavage plane along the apical/basal axis (Fig. 1).

In mammals, the ortholog of PINS is LGN. LGN binds with a microtubule-associated protein NuMA and Gαi to establish asymmetric microtubule orientation [33]. In the absence of LGN, PAR3 localizes exclusively to one cell and drives excessive production of outer radial glia [1].

In neoplasia

Dlg is an established tumor suppressor, with Drosophila mutants demonstrating loss of apico-basal polarity in imaginal discs during development, resulting in cellular enlargement. Absence of Dlg disrupts microfilament and microtubule network and disrupts the localization of basal determinants [1,34]. Inscuteable protein anchors mitotic spindles that assist with localization of basal determinants, such as Miranda and Prospero. In the absence of Inscuteable, symmetric cell division occurs rather than asymmetric, mostly due to Miranda and Prospero localizing randomly [7]. The Pins and Mud also interact with one another to establish proper spindle orientation. Loss of either (or both) results in a lack of spindle alignment with the asymmetric fate determinants, leading to their haphazard localization and resulting in the formation of proliferative neuroblasts-like cells [35].

Mouse LGN is closely related to Drosophila Pins and can rescue Pins mutants to maintain asymmetric division. Genetic mutation and siRNA experiments have shown that functional loss of LGN leads to disruption of asymmetry in radial glial cell division and leads to proliferation through oblique division as opposed to vertical division [8]. Overexpression of mammalian NuMA, an ortholog of Mud, results in aneuploidy in mouse myeloid cell [36] and may cause neoplastic growth in the setting of additional alterations, such as TP53 mutation [37].

A large number of human breast cancer cells show high levels of LGN protein expression [38], suggesting that its enhanced function may play a role in tumor development and progression. LGN is a target of PBK/TOPK for phosphorylation and subsequent activation of LGN drives symmetric spindle orientation, resulting in proliferation and tumor formation. Another well-known tumor suppressor in colorectal carcinoma, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), binds with human DLG1 protein and negatively regulates cell cycle progression [39]. APC also binds with β-catenin through GSK-3β and axin complex, eventually leading to β-catenin ubiquitination and degradation. This process normally attenuates WNT-signaling and suppresses cell proliferation, but the downstream effects are reversed in cancer following the genomic alteration of signaling network members [40,41].

Basal spindle orientation

In contrast to apical spindle organization, descriptions of proper basal spindle arrangement have not emerged as quickly. It has been assumed that Dlg and Pins promote basal spindle orientation since basal determinants do not localize in dlg and pins mutants; however, in these mutants asymmetric cell division can still occur during telophase [1]. Further investigation is needed in this space.

Extrinsic Regulators of Asymmetric Cell Division

Recent findings indicate that the microenvironment surrounding stem cells—the stem cell niche—also influences asymmetric cell division. Interestingly, whereas cell-intrinsic mechanisms appear to dominate in Drosophila neuroblasts, Drosophila germline stem cells have been a prime model for exploring niche effects. Stem cells in Drosophila ovary and testis are attached to elements of the stem cell niche known as cap and hub, respectively [42]. Physical attachment to these niche components allows maintenance of stemness, whereas detachment leads to differentiation. Therefore, germline stem cells orient their apico-basal polarity in such a way that the apical side remains attached, or at least in proximity, to niche elements that support stemness.

The role of Wnt as a determinant of cell polarity is firmly established in C. elegans and Drosophila [43] and recent investigations also indicate a prominent role in asymmetric cell division. For example, when immobilized WNT protein is brought into proximity of embryonic stem cells about to divide, the daughter cell closest to WNT will continue to display pluripotency, whereas the distant daughter is destined for differentiation [43].

Similar niche phenomena can be observed in in vivo mammalian systems, where neural and epidermal stem cells have been ideal models for investigation. In each of these systems, cells receive both intrinsic and extrinsic (niche driven) cues that guide asymmetric cell division [44]. Neural stem cells physically reside within the subventricular zone of lateral ventricle, attached to ependymal cells that line the ventricular surface [45]. During division, the daughter cell that loses contact with the ependymal niche proceeds to differentiate. Cellular growth factors from nearby blood vessels and cerebrospinal fluid have also been shown to promote neural stem cell proliferation [8]. Similar phenomena have been observed in embryonic epidermal cells: following division, daughter cells that lose contact with the basement membrane become differentiated suprabasal cells [8]. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Notch signaling pathways direct self-renewal in these settings [8]. Parallels with cancer biology are evident, since both activating EGFR alterations and dysregulated Notch signaling are common in cancer [46]. Thus, the stem cell niche plays an important role in asymmetric cell division, yet further studies are needed to clarify mechanisms at a deeper level.

Wnt is a bona fide proto-oncogene strongly linked to breast cancer, specific forms of medulloblastoma and other forms of neoplasia. Dysregulation of Wnt promotes nuclear localization of β-catenin, leading to target gene expression that promotes tumor progression and is associated with poor prognosis in some cancers. Wnt signaling (Fig. 1) is also a primary driver of EMT [43], which could result, at least partially, from dysregulation of asymmetric cell division. WNT signaling maintains mammary stem cell population early tumorigenic lesions of MMTV-Wnt1 transgenic mice [47]. Moreover, recruitment of WNT by the extracellular matrix component periostin promotes the maintenance of cancer stem cells [48].

Noncanonical Signaling Pathway Influence on Asymmetric Cell Division

Asymmetric localization of fate determining protein complexes and asymmetric spindle arrangement are fundamental cell-intrinsic drivers of bipolar stem cell division. While mechanisms have been partially established, initiating events or signals are not so forthcoming. There is emerging evidence suggesting that growth-signaling pathways may directly or indirectly influence the initiation and evolution of asymmetric cell division.

Myc regulation

MYC signaling pathways are key regulators of cell growth, proliferation, and development and have a strong impact on stem cell maintenance. Constitutively active c-MYC has been linked with many neoplastic diseases [49].

A link between asymmetric cell division and dMyc (Drosophila Myc) has been inferred in Drosophila neuroblasts and germline stem cells [50], as dMyc is expressed in stem cells but not differentiated cells. During asymmetric cell division, Drosophila Brat suppresses dMyc expression post-transcriptionally in neuroblasts [31] and in germline stem cells [51]. Thus, the self-renewing neuroblasts in Brat mutant express high levels of dMyc [31].

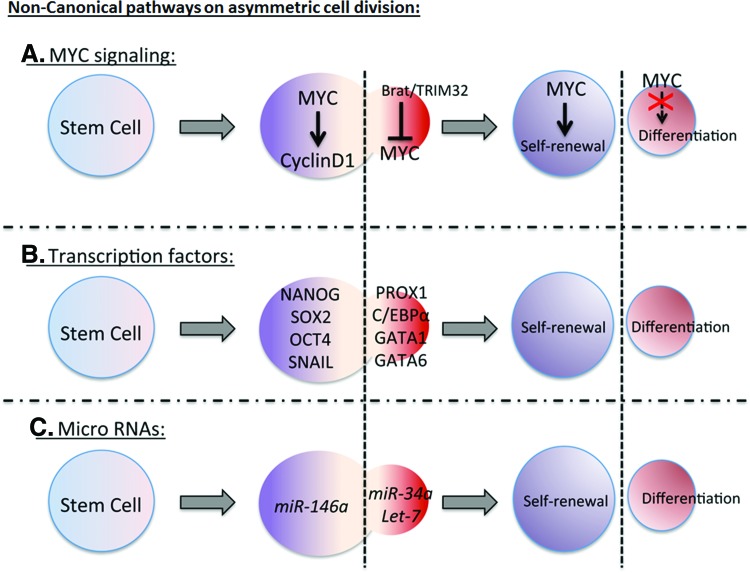

TRIM32, a mouse homolog of Drosophila Brat ubiquitinates c-MYC for its degradation in neural progenitors in neocortex (Fig. 2A) [1] leading to differentiation. c-MYC regulates cell cycle genes such as Cyclin D1 (Fig. 2A) [52], chromatin modification, and energy metabolism that promote cell division and stemness. Both Drosophila Myc and mammalian MYC bind to the promoter region of TORC1 target genes [50], suggesting a control over ribosome synthesis and Insulin/TOR metabolism axis driving self-renewal. Another potential mechanism is that MYC represses a master regulator of endoderm differentiation, GATA6 [50] and drives proliferation.

FIG. 2.

Noncanonical signaling pathways regulate asymmetric cell division. (A) Various growth-signaling pathways affect the asymmetric cell division balance. Progrowth regulators such as MYC shift the asymmetric cell division balance toward self-renewal, through activating CYCLIN D1. On the basal side, Drosophila Brat or mammalian TRIM32 attenuates MYC function to start differentiation signal. (B) Dysregulation of pluripotency and self-renewal transcription factors such as NANOG, SOX2, OCT4, and SNAIL also initiate symmetric stem cell proliferation. Transcription factors such as PROX1, C/EBP alpha, GATA1, GATA6 are expressed in the differentiated daughter cell. (C) MicroRNAs also regulate asymmetric cell division by affecting stem cell renewal and differentiation. miR-146a drives stem cell renewal, whereas miR-34a and Let-7 drive differentiation. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

The excessive activity of MYC in many cancers supports a strong relationship between carcinogenesis and the self-renewal program [53]. However, normal cellular safeguards appear to be broken in cancer. For example, in non-neoplastic follicular basal cells, aberrant c-MYC activation depletes the stem cell population and drives differentiation [54] suggesting a protective mechanism against uncontrolled proliferation in normal cells [54].

Self-renewal transcription factors and cell cycle regulation

Transcription factors best known for maintaining pluripotency include Nanog, Sox2, and Oct4 (Fig. 2B) [52]. These transcription factors have been shown to accumulate on the self-renewal side of embryonic stem cell during asymmetric cell division and are induced by WNT3a [43]. These factors regulate cell cycle and microRNA genes that sustain pluripotency and stem cell identity on the apical side. Copy number variation of pluripotent transcription factors is evident in many human neoplastic growths, confirming the contribution of these factors (Table 1).

Cell cycle regulators ultimately determine a cell's commitment to divide and create progeny. Their defects are known to drive specific diseases, including cancer. Cell cycle entry and exit are determined by protein interactions between cyclins and CDKs. During asymmetric cell division in mammals, Rho GTPase CDC42 [55] accumulates on the apical side along with the aPKC/PAR6/PAR3 complex. CDC42, like other GTPases activates transcription of CCND1 (Cyclin D1) mRNA in fibroblasts and epithelial cells [55]. Overexpression of CyclinD1/CDK4 in mice inhibits neurogenesis resulting in thicker subventricular zone with increased number of progenitors [56]. Cyclin D1/CDK4 controls G1-S cell cycle transition through the activation of E2F in stem cells [57]. High levels of Cyclin-CDK ensure short G1 phase in mice subventricular progenitor cells.

MicroRNA regulation

mi-RNA regulation of self-renewal (Fig. 2C), pluripotency, and asymmetric cell division are also relevant to cancer (Table 1). These short, noncoding RNAs target mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner and suppress their expression [58]. Many mi-RNAs are regulated by self-renewal transcriptional factors, such as Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2 [52]. In the context of asymmetric cell division, Drosophila protein Mei-P26 inhibits mi-RNA pathways and mutant mei-P26 flies show germline over proliferation [59]. The recently discovered microRNA miR-34a localizes asymmetrically and represses Notch signaling in differentiated daughter cells [60]. Pro-self-renewal properties of miR-146a have also been described in colorectal cancer stem cells [60], in which miR-146a phenocopies Snail-dependent colorectal cancers, likely because Snail regulates miR-146a through the Wnt signaling pathway. Let-7, another class of microRNA, regulates Ras oncogenic activity. In lung cancer, Let-7 is downregulated, thus driving the proliferation, rather than differentiation [61].

Loss of Asymmetric Division is Not Always Complete in Cancer

The complete loss of asymmetric cell division and its replacement by symmetric cell division is not a routine finding in cancer. Rather, mechanisms of asymmetric cell division are more often disrupted and likely influence the balance of stem cells and nonstem cells. Indeed, several asymmetric protein markers accumulate during division of cancer cells in both human disease and animal models, suggesting that asymmetric cell division still occurs [62,63]. In Drosophila, loss of one cell fate determinant such as brat, mira, numb, l(2)gl, and pros leads to an accumulation of neuroblasts. However, this loss does not stop the other determinants from arranging asymmetrically during cell division, suggesting that loss of asymmetry is only partial in some cases. As an example in human cancer, polyploid giant cancer cells have been described as having stem cell properties [62] and undergo asymmetric division. However, these cells are also in a dynamic equilibrium with a nonstem cell population and capable of phenotypic reversion [64]. These data and others suggest that deregulation of asymmetric cell division in cancer is not always absolute or complete, but rather disrupts the stem/progeny equilibrium in a manner that favors abnormal growth properties.

Summary

Mechanisms of asymmetric cell division are necessarily complex and much of our current understanding derives from Drosophila [44].

• Early localization of apical and basal fate-determining protein complexes direct bipolar division and disruption drives division toward symmetry, generating stem cells with potential to generate neoplastic masses.

• Asymmetric arrangement of spindles and microtubules also play a critical role in asymmetric cell division.

• Mammalian systems have cell-extrinsic (micro-environmental) cues that impact asymmetric cell division.

• Noncanonical pathways that indirectly influence asymmetric cell division include transcription factors, cell cycle regulators, signaling pathways, and microRNAs.

Many cancers display disrupted asymmetric cell division [8], which may be explained by disturbances of mechanisms above. Further understanding of stem cell division in cancer will provide opportunities for the development of novel diagnostics and therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01CA149107 and the Georgia Research Alliance (D.J.B.).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Knoblich JA. (2010). Asymmetric cell division: recent developments and their implications for tumour biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11:849–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yong KJ. and Yan B. (2011). The relevance of symmetric and asymmetric cell divisions to human central nervous system diseases. J Clin Neurosci 18:458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conklin EG. (1905). The mutation theory from the standpoint of cytology. Science 21:525–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita YM, Mahowald AP, Perlin JR. and Fuller MT. (2007). Asymmetric inheritance of mother versus daughter centrosome in stem cell division. Science 315:518–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bultje RS, Castaneda-Castellanos DR, Jan LY, Jan YN, Kriegstein AR. and Shi SH. (2009). Mammalian Par3 regulates progenitor cell asymmetric division via notch signaling in the developing neocortex. Neuron 63:189–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troy A, Cadwallader AB, Fedorov Y, Tyner K, Tanaka KK. and Olwin BB. (2012). Coordination of satellite cell activation and self-renewal by Par-complex-dependent asymmetric activation of p38alpha/beta MAPK. Cell Stem Cell 11:541–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chia W, Somers WG. and Wang H. (2008). Drosophila neuroblast asymmetric divisions: cell cycle regulators, asymmetric protein localization, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Biol 180:267–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez-Lopez S, Lerner RG. and Petritsch C. (2014). Asymmetric cell division of stem and progenitor cells during homeostasis and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:575–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Sato C, Cerletti M. and Wagers A. (2010). Notch signaling in the regulation of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Curr Top Dev Biol 92:367–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal N, Kango M, Mishra A. and Sinha P. (1995). Neoplastic transformation and aberrant cell-cell interactions in genetic mosaics of lethal(2)giant larvae (lgl), a tumor suppressor gene of Drosophila. Dev Biol 172:218–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaiano N, Nye JS. and Fishell G. (2000). Radial glial identity is promoted by Notch1 signaling in the murine forebrain. Neuron 26:395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viloria-Petit AM, David L, Jia JY, Erdemir T, Bane AL, Pinnaduwage D, Roncari L, Narimatsu M, Bose R, et al. (2009). A role for the TGFbeta-Par6 polarity pathway in breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:14028–14033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou C, Ding L, Zhang J, Jin Y, Sun C, Li Z, Sun X, Zhang T, Zhang A, Li H. and Gao J. (2014). Abnormal cerebellar development and Purkinje cell defects in Lgl1-Pax2 conditional knockout mice. Dev Biol 395:167–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunnev D, Ivanov I. and Ionov Y. (2009). Par-3 partitioning defective 3 homolog (C. elegans) and androgen-induced prostate proliferative shutoff associated protein genes are mutationally inactivated in prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer 9:318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothenberg SM, Mohapatra G, Rivera MN, Winokur D, Greninger P, Nitta M, Sadow PM, Sooriyakumar G, Brannigan BW, et al. (2010). A genome-wide screen for microdeletions reveals disruption of polarity complex genes in diverse human cancers. Cancer Res 70:2158–2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen G, Kong J, Tucker-Burden C, Anand M, Rong Y, Rahman F, Moreno CS, Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG. and Brat DJ. (2014). Human Brat ortholog TRIM3 is a tumor suppressor that regulates asymmetric cell division in glioblastoma. Cancer Res 74:4536–4548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komori H, Xiao Q, McCartney BM. and Lee CY. (2014). Brain tumor specifies intermediate progenitor cell identity by attenuating beta-catenin/Armadillo activity. Development 141:51–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arama E, Dickman D, Kimchie Z, Shearn A. and Lev Z. (2000). Mutations in the beta-propeller domain of the Drosophila brain tumor (brat) protein induce neoplasm in the larval brain. Oncogene 19:3706–3716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonoda J. and Wharton RP. (2001). Drosophila brain tumor is a translational repressor. Genes Dev 15:762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vessey JP, Amadei G, Burns SE, Kiebler MA, Kaplan DR. and Miller FD. (2012). An asymmetrically localized Staufen2-dependent RNA complex regulates maintenance of mammalian neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 11:517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heitzler P. and Simpson P. (1991). The choice of cell fate in the epidermis of Drosophila. Cell 64:1083–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caussinus E. and Gonzalez C. (2005). Induction of tumor growth by altered stem-cell asymmetric division in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet 37:1125–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaucher M, Hersperger E, Page-McCaw A. and Shearn A. (2007). Metastatic ability of Drosophila tumors depends on MMP activity. Dev Biol 303:625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janic A, Mendizabal L, Llamazares S, Rossell D. and Gonzalez C. (2010). Ectopic expression of germline genes drives malignant brain tumor growth in Drosophila. Science 330:1824–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi M, Yoshimoto T, Shimoda M, Kono T, Koizumi M, Yazumi S, Shimada Y, Doi R, Chiba T. and Kubo H. (2006). Loss of function of the candidate tumor suppressor prox1 by RNA mutation in human cancer cells. Neoplasia 8:1003–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagai H, Li Y, Hatano S, Toshihito O, Yuge M, Ito E, Utsumi M, Saito H. and Kinoshita T. (2003). Mutations and aberrant DNA methylation of the PROX1 gene in hematologic malignancies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 38:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudas J, Mansuroglu T, Moriconi F, Haller F, Wilting J, Lorf T, Fuzesi L. and Ramadori G. (2008). Altered regulation of Prox1-gene-expression in liver tumors. BMC Cancer 8:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versmold B, Felsberg J, Mikeska T, Ehrentraut D, Kohler J, Hampl JA, Rohn G, Niederacher D, Betz B, et al. (2007). Epigenetic silencing of the candidate tumor suppressor gene PROX1 in sporadic breast cancer. Int J Cancer 121:547–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulay JL, Stiefel U, Taylor E, Dolder B, Merlo A. and Hirth F. (2009). Loss of heterozygosity of TRIM3 in malignant gliomas. BMC Cancer 9:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Raheja R, Yeh N, Ciznadija D, Pedraza AM, Ozawa T, Hukkelhoven E, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. (2014). TRIM3, a tumor suppressor linked to regulation of p21(Waf1/Cip1). Oncogene 33:308–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betschinger J, Mechtler K. and Knoblich JA. (2006). Asymmetric segregation of the tumor suppressor brat regulates self-renewal in Drosophila neural stem cells. Cell 124:1241–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wodarz A, Ramrath A, Kuchinke U. and Knust E. (1999). Bazooka provides an apical cue for Inscuteable localization in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature 402:544–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du Q. and Macara IG. (2004). Mammalian Pins is a conformational switch that links NuMA to heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell 119:503–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods DF, Hough C, Peel D, Callaini G. and Bryant PJ. (1996). Dlg protein is required for junction structure, cell polarity, and proliferation control in Drosophila epithelia. J Cell Biol 134:1469–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wodarz A. and Nathke I. (2007). Cell polarity in development and cancer. Nat Cell Biol 9:1016–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ota J, Yamashita Y, Okawa K, Kisanuki H, Fujiwara S, Ishikawa M, Lim Choi Y, Ueno S, Ohki R, et al. (2003). Proteomic analysis of hematopoietic stem cell-like fractions in leukemic disorders. Oncogene 22:5720–5728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vang R, Shih Ie M. and Kurman RJ. (2009). Ovarian low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma: pathogenesis, clinicopathologic and molecular biologic features, and diagnostic problems. Adv Anat Pathol 16:267–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukukawa C, Ueda K, Nishidate T, Katagiri T. and Nakamura Y. (2010). Critical roles of LGN/GPSM2 phosphorylation by PBK/TOPK in cell division of breast cancer cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 49:861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumine A, Ogai A, Senda T, Okumura N, Satoh K, Baeg GH, Kawahara T, Kobayashi S, Okada M, Toyoshima K. and Akiyama T. (1996). Binding of APC to the human homolog of the Drosophila discs large tumor suppressor protein. Science 272:1020–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawahara K, Morishita T, Nakamura T, Hamada F, Toyoshima K. and Akiyama T. (2000). Down-regulation of beta-catenin by the colorectal tumor suppressor APC requires association with Axin and beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 275:8369–8374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Zhang W, Evans PM, Chen X, He X. and Liu C. (2006). Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) differentially regulates beta-catenin phosphorylation and ubiquitination in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem 281:17751–17757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roeder I. and Lorenz R. (2006). Asymmetry of stem cell fate and the potential impact of the niche: observations, simulations, and interpretations. Stem Cell Rev 2:171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Habib SJ, Chen BC, Tsai FC, Anastassiadis K, Meyer T, Betzig E. and Nusse R. (2013). A localized Wnt signal orients asymmetric stem cell division in vitro. Science 339:1445–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knoblich JA. (2008). Mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. Cell 132:583–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doetsch F. (2003). A niche for adult neural stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev 13:543–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Espinoza I, Pochampally R, Xing F, Watabe K. and Miele L. (2013). Notch signaling: targeting cancer stem cells and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Onco Targets Ther 6:1249–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat ML, Wu L, Lindeman GJ. and Visvader JE. (2006). Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature 439:84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malanchi I, Santamaria-Martinez A, Susanto E, Peng H, Lehr HA, Delaloye JF. and Huelsken J. (2012). Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature 481:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng H, Ying H, Yan H, Kimmelman AC, Hiller DJ, Chen AJ, Perry SR, Tonon G, Chu GC, et al. (2008). Pten and p53 converge on c-Myc to control differentiation, self-renewal, and transformation of normal and neoplastic stem cells in glioblastoma. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 73:427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinn LM, Secombe J. and Hime GR. (2013). Myc in stem cell behaviour: insights from Drosophila. Adv Exp Med Biol 786:269–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris RE, Pargett M, Sutcliffe C, Umulis D. and Ashe HL. (2011). Brat promotes stem cell differentiation via control of a bistable switch that restricts BMP signaling. Dev Cell 20:72–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kapinas K, Grandy R, Ghule P, Medina R, Becker K, Pardee A, Zaidi SK, Lian J, Stein J, van Wijnen A. and Stein G. (2013). The abbreviated pluripotent cell cycle. J Cell Physiol 228:9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nesbit CE, Tersak JM. and Prochownik EV. (1999). MYC oncogenes and human neoplastic disease. Oncogene 18:3004–3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Losada J. and Balmain A. (2003). Stem-cell hierarchy in skin cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 3:434–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Besson A, Assoian RK. and Roberts JM. (2004). Regulation of the cytoskeleton: an oncogenic function for CDK inhibitors?. Nat Rev Cancer 4:948–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lange C, Huttner WB. and Calegari F. (2009). Cdk4/cyclinD1 overexpression in neural stem cells shortens G1, delays neurogenesis, and promotes the generation and expansion of basal progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 5:320–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kondo T, Ezzat S. and Asa SL. (2006). Pathogenetic mechanisms in thyroid follicular-cell neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer 6:292–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kapinas K. and Delany AM. (2011). MicroRNA biogenesis and regulation of bone remodeling. Arthritis Res Ther 13:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Page SL, McKim KS, Deneen B, Van Hook TL. and Hawley RS. (2000). Genetic studies of mei-P26 reveal a link between the processes that control germ cell proliferation in both sexes and those that control meiotic exchange in Drosophila. Genetics 155:1757–1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lerner RG. and Petritsch C. (2014). A microRNA-operated switch of asymmetric-to-symmetric cancer stem cell divisions. Nat Cell Biol 16:212–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esquela-Kerscher A. and Slack FJ. (2006). Oncomirs—microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6:259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang D, Wang Y. and Zhang S. (2014). Asymmetric cell division in polyploid giant cancer cells and low eukaryotic cells. Biomed Res Int 2014:432652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neumuller RA. and Knoblich JA. (2009). Dividing cellular asymmetry: asymmetric cell division and its implications for stem cells and cancer. Genes Dev 23:2675–2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang S, Mercado-Uribe I, Xing Z, Sun B, Kuang J. and Liu J. (2014). Generation of cancer stem-like cells through the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene 33:116–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, Vivanco I, Lee JC, Huang JH, et al. (2007). Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:20007–20012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peifer M, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Sos ML, George J, Seidel D, Kasper LH, Plenker D, Leenders F, Sun R, et al. (2012). Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet 44:1104–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, Park K, Kitabayashi N, MacDonald TY, et al. (2013). Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell 153:666–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, et al. (2013). Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 497:67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. (2011). Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474:609–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, Chaudhuri S, Guan Y, Janakiraman V, et al. (2012). Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature 488:660–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reinhold WC, Sunshine M, Liu H, Varma S, Kohn KW, Morris J, Doroshow J. and Pommier Y. (2012). CellMiner: a web-based suite of genomic and pharmacologic tools to explore transcript and drug patterns in the NCI-60 cell line set. Cancer Res 72:3499–3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, Nickerson E, Auclair D, Li L, et al. (2012). A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell 150:251–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. (2014). Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 507:315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. (2012). Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature 489:519–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, Evans P, Bacchiocchi A, McCusker JP, Cheng E, Davis MJ, Goh G, et al. (2012). Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet 44:1006–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, et al. (2008). Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 455:1069–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, et al. (2012). The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483:603–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ho AS, Kannan K, Roy DM, Morris LG, Ganly I, Katabi N, Ramaswami D, Walsh LA, Eng S, et al. (2013). The mutational landscape of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat Genet 45:791–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, Ferrara TM, Ben S, Riccardi SL, Cole JB, Gowan K, Holland PJ, et al. (2012). Genome-wide association analyses identify 13 new susceptibility loci for generalized vitiligo. Nat Genet 44:676–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]