Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the study was to compare the outcome of laparoscopic sacral colpocervicopexy with laparoscopic pectopexy. Our aim was to show that the safety and effectiveness of the new technique is similar to the traditional technique. We expected differences regarding defecation disorders.

Patients and Methods: We randomly assigned patients to two treatment groups: 44 in the pectopexy and 41 in the sacropexy group. If necessary, the operative procedures were planned in a so-called multicompartment setting regarding the different pelvic floor disorders. All defects were managed at the same time. Eighty-one patients were examined 12 to 37 months after treatment (mean follow-up 20.67 months).

Results: The long-term follow-up (21.8 months for pectopexy and 19.5 months for sacropexy) showed a clear difference regarding de novo defecation disorders (0% in the pectopexy vs 19.5% in the sacropexy group). The incidence of de novo stress urinary incontinence was 4.8% (pectopexy) vs 4.9% (sacropexy). The incidence of rectoceles (9.5% vs 9.8%) was similar in both groups. No de novo lateral defect cystoceles were found after pectopexy, whereas 12.5% were found after sacropexy. The apical descensus relapse rates, 2.3% for pectopexy vs 9.8% for sacropexy, were not statistically significant. The occurrence of de novo anterior defect cystoceles and rectoceles revealed no significant differences.

Conclusion: Laparoscopic pectopexy is a novel method of vaginal prolapse therapy that offers clear practical advantages compared with laparoscopic sacropexy. Because laparoscopic pectopexy does not reduce the pelvic space, it results in a zero percentage of defecation disorders.

Introduction

Sacropexy has been a well-known technique in prolapse surgical procedures for many decades. The main focus of the procedure is the repair of the apical defect.1,2 Numerous publications show that sacropexy seems to be the most adequate approach for the reconstitution of a physiologic axis of the vagina regarding size, depth, and slant.3–5 Sacropexy has been performed laparoscopically since the 1990s; however, there is a bias in comparability because different techniques have been applied. Many surgeons prefer to fix a mesh directly on the promontory and recommend a deep preparation of the vagina for the management of cysto- and rectoceles.6,7 Others use the longitudinal ligament at the height of the second sacral vertebra (S2)8 for the mesh fixation and manage the different compartments with additional techniques.

Frequent outcomes after sacropexy are defecation disorders and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In our opinion, defecation disorders have been underestimated in the past. In studies dealing with sacropexy via laparotomy and also via laparoscopy, problems with flatulence, constipation, and chronic pain are frequently reported.9–15 The cause of the defecation disorders can be less space in the pelvis (outlet obstruction), adhesions, or trauma of the hypogastric nerves.16

In 2007, we first described the pectopexy as a new technique for apical repair.17 This method uses the iliopectineal ligament on both sides for the mesh fixation,17 so there is no restriction caused by the mesh. The mesh follows natural structures (round and broad ligaments) without crossing sensitive spots, such as the ureter or bowel. The hypogastric trunk is at a safe distance and out of danger. As shown by Cosson and associates,18 the iliopectineal ligament is statistically significantly stronger than the sacrospinous ligament and the arcus tendineus of the pelvic fascia. In the lateral part of the iliopectineal ligament, it is always possible to find enough material for a suture. The height of the lateral fixation corresponds to the level S2. The anterior longitudinal ligament is used for the fixation when performing a sacral colpopexy. To achieve a physiologic axis of the vagina, the cranial anchor point should be at the S2 level.

In our randomized trial, we intended to demonstrate that the pectopexy is at least equivalent to the sacral colpopexy in respect to the relapse rate of apical descensus. We expected a better long-term outcome because of the lower probability of disorders caused by narrowing of the pelvis. In addition, we intended to prove that pectopexy, compared with sacropexy, offers clear practical advantages to the surgeon because of a less hazardous preparation. We postulate that pectopexy extends the portfolio of surgical options and enables the surgeon to react more adequately in complex surgical conditions. Because we expected no great differences in the outcome of the techniques, this study serves as a pilot study for the design of a following multicenter noninferiority study.

Patients and Methods

Indication and participants

Because the aim of the study was to prove that laparoscopic pectopexy should be considered an alternative to sacropexy, the indication for both interventions was the presence of an apical defect.

Generally, patients complained of symptoms related to the vaginal protrusion (vaginal pressure, lower back pain, dyspareunia, and other sexually related symptoms) or associated symptoms of the urinary bladder (urinary incontinence or urinary retention). The extension of the genital prolapse was assessed by a physical examination as well as via ultrasonography. We used the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q) for prolapse assessment. The patients were examined in a lying and in a sitting position to assess the influence of pressure. This preoperative evaluation was important to prevent an over- or under-correction and provided valuable information about the quality of connective tissue.

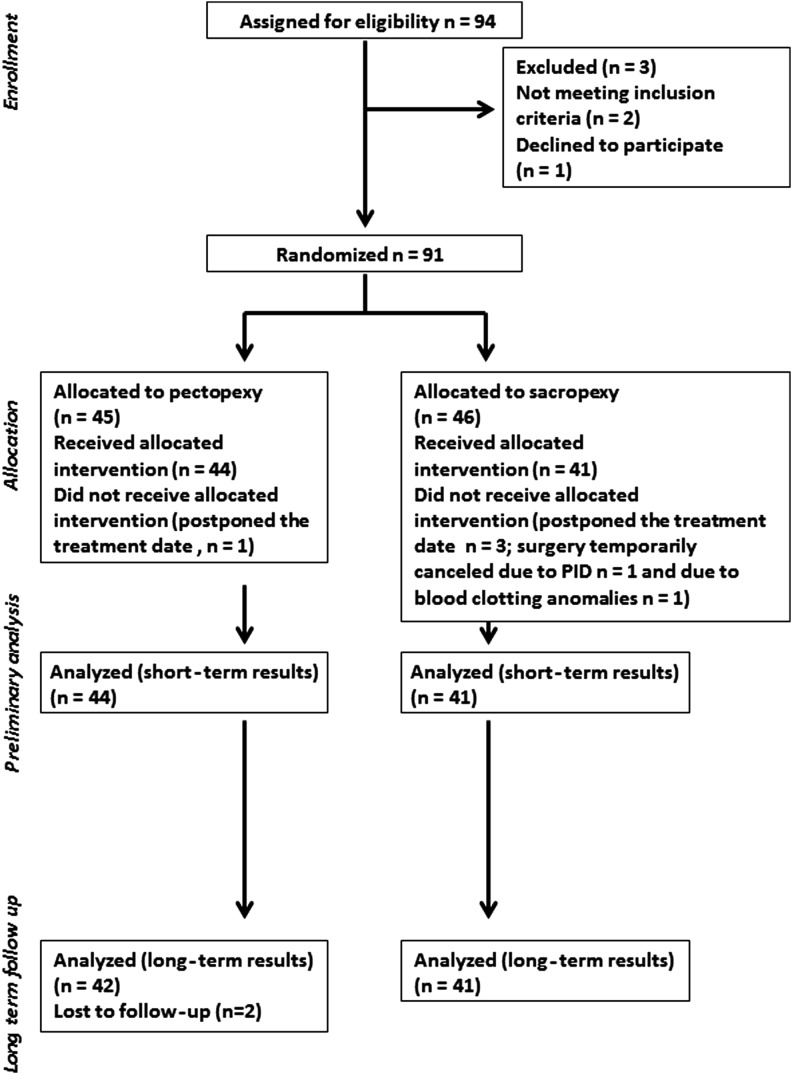

This prospective, randomized trial to compare the standard laparoscopic sacral colpopexy with the laparoscopic pectopexy was approved by the ethics committee of the Ruhr-University Bochum. The study design is shown in Figure 1.19 Only patients with symptomatic primary vaginal prolapse POP-Q≥II were eligible for inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria were previous operations for vaginal prolapse correction, pelvic inflammatory disease, and contraindications to one of the surgical methods applied in the study, thereby making randomization impossible (e.g., previously identified or strongly suspected massive adhesions between the sigmoid colon and presacral peritoneum). Patients unable to speak German were excluded from the study. All participants submitted a written informed consent form. The study was performed according to the CONSORT statement.

FIG. 1.

Study design.

We documented the relapse occurrence of apical prolapse as well as the incidence of de novo urgency, SUI, anterior and lateral defect cystoceles, rectoceles, and constipation. The defecation disorders were documented using the defecation section of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) (International Continence Society). We also recorded the degree of satisfaction with the surgery.

Randomization and statistics

We randomized patients by opening numbered and sealed, nontransparent envelopes. An independent person randomly assigned a total number of 94 cards (47 cards for each intervention) to the envelopes and sealed them. The sealed envelopes were shuffled before numbering. Neither the medical team nor the patients were blinded to the intervention.

The statistical evaluation of the study results was performed using Systat® software (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL). Follow-up time was assessed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. All other parameters were analysed with the Fisher exact test. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Follow-up

The follow-up time was set to be at least 1 year after the surgical procedure. The evaluation comprised the clinical description of vaginal prolapse, according to the POP-Q criteria. We recorded follow-up time, relapse rates for apical descensus, de novo occurrence of lateral-defect cystocele, urgency, SUI, and constipation. We also assessed the rate of de novo cases and relapse of central-defect cystocele and rectocele. For central-defect cystocele, apical descensus, and rectocele, the definition of relapse and de novo defect was set at pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q)≥II (the same level as for enrollment into the study). Patient satisfaction with the intervention was also recorded.

Operative procedures

All operations were performed using standard endoscopic equipment (a 10-mm optical device inserted via a 12-mm trocar and 5-mm instruments). The optical device was placed via the umbilical trocars, and the instruments were introduced through three incisions in the lower abdomen (median, left, and right cut 2–4 cm medial and inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine).

In patients who had not undergone a hysterectomy, we preferred to conduct a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy in combination with the prolapse correction to achieve a more stable fixation of the apical region.

If multiple pelvic floor defects were present, we performed a simultaneous correction in the same operative session as the pectopexy or sacropexy. The number of additional interventions performed in each study group is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Accompanying Interventions

| Pectopexy | Sacral colpo-/cervicopexy | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 42 | 41 |

| Average age (years) | 62.1 | 61.1 |

| Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (number of patients) | 32 | 27 |

| Anterior colporrhaphy (number of patients) | 21 | 19 |

| Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension (number of patients) | 4 | 4 |

| Laparoscopic lateral repair (number of patients) | 10 | 8 |

| Posterior colporrhaphy (number of patients) | 16 | 22 |

All patients were advised to continue the low-dose vaginal estriol treatment, which was started postoperatively, for at least 6 to 8 weeks after the procedure. We also recommended regular pelvic floor exercise—however, not until 6 to 8 weeks after the procedure to provide adequate healing and scar tissue formation.

Pectopexy

We performed this procedure as described previously.7 We opened the peritoneal layer along the right round ligament toward the pelvic wall. The preparation started at the right external iliac vein and was carried out in the medial and caudal direction under intermittent bipolar coagulation. We exposed an approximately 4-cm segment of the right iliopectineal ligament (Cooper ligament) adjacent to the insertion of the ileopsoas muscle. This segment of the ligament was situated at the S2 level. Special care was taken to avoid any contact with the obturator nerve, situated caudal to our region of interest. The same preparation was repeated on the left side of the patient. The incisions on both sides were connected by opening the peritoneal layer toward the cervical stump/vaginal apex. In patients who had undergone a complete hysterectomy, the peritoneum was dissected, and the anterior and posterior parts of the vaginal apex were prepared for the mesh fixation.

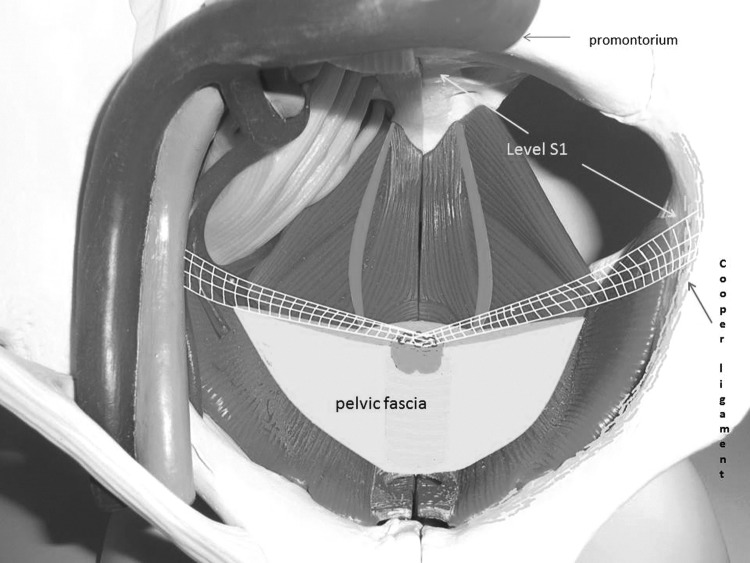

The next step started with the insertion of a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) monofilament mesh (e.g., DynaMesh® PVDF, 3×15 cm) into the abdominal cavity. The mesh ends were attached to both iliopectineal ligaments endoscopically using nonabsorbable suture material. The cervical stump or vaginal apex, respectively, was elevated to the intended tension-free position; the fixation was performed using either nonabsorbable suture material (for cervical stump) or polydioxanone suture (PDS®) (for vaginal apex). A hammock-like fixation of the cervix/vaginal apex resulted. Finally, we covered the mesh with peritoneum using absorbable suture material in a continuous endoscopic suturing technique (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Bilateral mesh-fixation at the iliopectineal ligament and the cervical stump. Fixation level: Sacral vertebra 1.

Sacral colpopexy

To restore the physiological vaginal axis, we attached the mesh below the level of the promontory. The peritoneal layer over the promontory was pulled up gently and then incised. After the incision, the peritoneal preparation was performed by blunt dissection; this step was facilitated by CO2 that entered the incision from the abdominal cavity. We continued the preparation along the right pelvic wall toward the cervix/vaginal stump.

A PVDF monofilament mesh (3×15 cm) was then inserted into the abdominal cavity. The mesh was attached to the longitudinal ligament with two parallel lines of continuous endoscopic sutures (non-absorbable suture material). The first stitch was performed between S2 and S3 and then four to five ascending stitches followed in a line towards the promontory. The last suture came to lie over the promontory. After the second suture line was completed, the mesh was pulled tightly to the sacral bone and fixed to the longitudinal ligament by knotting both threads over the promontory.

The other (distal) end of the mesh was attached to the cervical stump or vaginal apex, respectively, in a tension-free manner. The fixation was performed in the same way as the pectopexy using either nonabsorbable suture material (for cervical stump) or PDS (for vaginal apex). We performed the peritoneal closure over the mesh in the same manner as for pectopexy (continuous endoscopic suturing with absorbable material).

Results

There were no significant differences in the duration of the follow-up period between the two study groups (Table 2). The occurrence of de novo constipation was significantly higher in the sacropexy group. De novo lateral-defect cystocele did not occur in the pectopexy group (5 cases in the sacropexy group); this difference showed a strong correlation, but did not reach the defined level of statistical significance. We reported one relapse of the apical prolapse after cervical pectopexy (POP-Q II) and four relapses in the sacropexy group (one sacral colpopexy and three sacral cervicopexies, two of them POP-Q II and two POP-Q III cases), although these differences were of no statistical significance. All other evaluated parameters revealed no significant differences. The therapy satisfaction rates were high in both groups and also showed no significant differences.

Table 2.

Follow-Up Results

| Pectopexy | Sacral colpo-/cervicopexy | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 42 | 41 | |

| Average observation time (months) | 21.8 (range 12–35) | 19.5 (range 12–37) | 0.164 |

| Satisfied with the surgery (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 41; 97.6% | 39; 95.1% | |

| Relapse of apical descensus (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 1; 2.3% | 4; 9.8% | 0.361 |

| De novo central-defect cystocele or exacerbation of already existent central-defect cystocele (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 3; 7.1% | 2, 4.9% | 1.000 |

| De novo lateral-defect cystocele (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 0 | 5, 12.2% | 0.026 |

| De novo rectocele or exacerbation of already existent rectocele (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 4; 9.5% | 4; 9.8% | 1.000 |

| De novo constipation (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 0 | 8; 19.5% | 0.002 |

| De novo urgency (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 3; 7.1% | 7; 17.0% | 0.194 |

| De novo stress urinary incontinence (number of patients; percentage of all patients) | 2; 4.8% | 2, 4.9% | 1.000 |

Discussion

Sacral colpopexy can be considered the “gold standard” in the correction of vaginal vault prolapse,4,5,11,13 especially for the correction of apical defects. For more than 20 years, apical prolapse repair has been performed laparoscopically. Because of the difficult surgical field at the ventral side of the sacrum, many surgeons modified the technique and fixed the mesh to the top of the promontory.6,7 With the vaginal axis indicating to S2, the fixation at the promontory brought a positional change in direction to the abdominal wall.

In recent years, many studies have published reports of high de novo SUI rates (>25%) after sacrocolpopexy.7,20,21 Some authors have reported rates of up to 50%,22 but other studies, which recommend combination surgery and classical anchor points at the level of S2,8,23 have found lower SUI rates in the follow-up period. In view of the published data, it seems obvious not to recommend changing the vaginal axis by choosing a different anchor point and to avoid traction at the urethral entrance to the bladder. In our study, we found approximately 5% de novo SUI in both groups. Neither the pectopexy nor the sacropexy led to an axis deviation in our setting. If required, the procedures were performed in a multicompartment strategy.

Defecation disorders are often neglected; however, we found data that showed 17% to 37% de novo defecation problems after sacrocolpopexy.9,12,14,15 The patients mainly complained of constipation. The sacrocolpopexy, because of the anchor point (usually at the right side of the sacral longitudinal ligament), reduces the space of the pelvis. This can cause additional problems with fatty tissue in case of obesity or postinflammatory alterations of the sigmoid. Preparation of the anterior sacral bone also carries the risk of injuring the hypogastric nerves.16

As already mentioned, in our study, we found low de novo SUI rates of 4.8% (pectopexy) and 4.9% (sacropexy). This may support the multicompartment strategy regarding all defects and clinical risks for de novo SUI. As expected, no defecation disorders were recorded in the pectopexy group because the technique neither reduces the space of the pelvis nor bears the risk of damaging the autonomous nerves. In the sacropexy group, we found a de novo constipation rate of 19.5%. This was a statistically significant difference to the pectopexy group and more than we had expected.

Frequently, in prolapse and incontinence surgical procedures, a tension-free procedure is demanded. In our opinion, the defect-oriented strategy, with regard to the different compartments, allows the best opportunity to avoid too much traction. One of our positive findings was that we had no de novo lateral defects in the pectopexy group and 12.5% in the sacropexy group. Because the difference was statistically significant, the pectopexy probably has a protective effect on the anterior lateral compartment. We could not find comparable data in other studies.

In our study group, we did not see new risks for the pectopexy technique. The placement of the mesh interferes with no pelvic structures and so reduces the risk of bowel infection or disorders to zero. There might additionally be a protective influence on the anterior compartment. Both pectopexy and laparoscopic sacral colpopexy, however, should only be performed by experienced surgeons. The pectopexy technique can enlarge a surgeon's technical portfolio. In case of difficulties caused by anatomic variations, we strongly recommend the laparoscopic pectopexy as an alternative to sacral colpopexy. Multicenter investigations should be considered to prove the value of laparoscopic pectopexy in clinical routine.

Conclusion

The laparoscopic pectopexy is a good alternative to the laparoscopic sacropexy. It is equally effective and shows no defecation disorders in the long-term follow-up.

Abbreviations Used

- PDS

polydioxanone suture

- POP-Q

pelvic organ prolapse quantification

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- S2

sacral vertebra 2

- SUI

stress urinary incontinence

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ross JW. Apical vault repair, the cornerstone or pelvic vault reconstruction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1997;8:14–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn BJ, Webster GD. Surgical management of the apical vaginal defect. Curr Opin Urol 2002;12:353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beer M, Kuhn A. Surgical techniques for vault prolapse: A review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;119:144–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: A comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:805–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD004014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akladios CY, Dautun D, Saussine C, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for female genital organ prolapse: Establishment of a learning curve. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010;149:218–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarlos D, Brandner S, Kots L, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for uterine and post-hysterectomy prolapse: Anatomical results, quality of life and perioperative outcome—A prospective study with 101 cases. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:1415–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee C, et al. Complications, re-prolapse rates and functional results after laparoscopic sacropexy: A cohort study. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 2010;70:379–384 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder TE, Krantz KE. Abdominal-retroperitoneal sacral colpopexy for the correction of vaginal prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:944–949 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan ES, Longaker CJ, Lee PY. Total pelvic mesh repair: A ten-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:857–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culligan PJ, Murphy M, Blackwell L, et al. Long-term success of abdominal sacral colpopexy using synthetic mesh. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:1473–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baessler K, Schuessler B. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and anatomy and function of the posterior compartment. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:678–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieminen K, Heinonen PK. Long-term outcome of abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. J Pelvic Surg 2000;5:254–260 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilsgaard K, Mouritsen L. Follow-up after repair of vaginal vault prolapse with abdominal colposacropexy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:66–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virtanen H, Hirvonen T, Mäkinen J, Kiilholma P. Outcome of thirty patients who underwent repair of posthysterectomy prolapse of the vaginal vault with abdominal sacral colpopexy. J Am Coll Surg 1994;178:283–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiozawa T, Huebner M, Hirt B, et al. Nerve-preserving sacrocolpopexy: Anatomical study and surgical approach. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010;152:103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee C, Noé KG. Laparoscopic pectopexy: A new technique of prolapse surgery for obese patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosson M., Boukerrou M, Lacaze S, et al. A study of pelvic ligament strength. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;109:80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leruth J, Fillet M, Waltregny D. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative stress urinary incontinence following laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy in patients with negative preoperative prolapse reduction stress testing. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:485–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan CM, Liang HH, Go WW, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for uterine and post-hysterectomy prolapse: Anatomical and functional outcomes. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:301–305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.North CE, Ali-Ross NS, Smith AR, Reid FM. A prospective study of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for the management of pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG 2009;116:1251–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoshbakht N, Alarab M, Lovatsis D. Stress urinary incontinence six months post laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:653–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]