Abstract

Background: Cell-based therapies can be used to treat neurological diseases and spinal cord injuries. The aim of this study was to assess the clinical outcome of bone marrow derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) transplantation in patients with spinal cord injuries.

Methods: Following a systematic review to detect clinical intervention studies, a meta-analysis was done for pooling data to estimate the outcome of BM-MNCs transplantation. The percentage of the patients with improved ASIA scale from one grade to a higher grade was defined as the main outcome. By considering the study design and outcome measurement, two reviewers independently extracted the data.

Results: Eight relevant primary studies were found; seven qualified studies, with a combined total of 328 patients were assessed by meta-analysis, including 314 ASIA-A, 13 ASIA-B, 94 cervical, 227 thoracic and 60 acute injuries. The percentage of the patients’ improvement was tested by meta-analysis through random and fixed models. The overall percentage of all patients’ improved ASIA scale after a one- year follow-up (95% CIs) was 43 (0.27-0.59).

Conclusion: Data from published trials revealed that encouraging results were achieved by autologous BMMNCs for the treatment of spinal cord injury. However, the number of clinical trials included in the systematic review was too limited to reach a definite conclusion. More qualified clinical trials with standardized methods are needed to truly justify the outcome of this therapeutic modality in SCI patients.

Keywords: Cell Transplantation, Bone Marrow Derived Mononuclear Cells, Spinal Cord Injury

Introduction

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) occurs with a worldwide incidence of 15–40 cases per million people annually (1).Epidemiological data concerning the global prevalence of SCI is inaccessible. Also, it is appraised that more than 130,000 patients suffer from SCI per year. The mean age of spinal cord injury patients is 30 years, demonstrating that it disables persons in the prime of their lives. The high rate of incidence in adolescent groups is reasoned to the road accidents and sports related damages (2).Up to now, there is no cure available for these individuals, and SCI usually leads to important life-long disability (3,4). Despite a lack of internationally accepted scientific evidences, cell-based therapies offer great promise for many currently intractable conditions including neurological disorders. Frequently mentioned targets include neurological diseases and spinal cord injury (5). Different cell types have been studied in animal models and clinical trials. The bone marrow derived from mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) is extracted from the bone marrow directly, or it is derived via mobilization into the peripheral blood using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) (6). BM-MNCs are the most common cell population used in neuropathologic insults. These cells have many advantages including easy and rapid isolation with minimal manipulation, ample cell number, low processing costs and a minimally invasive bone marrow harvest procedure (7).BM-MNCs have been reported to promote repair and regeneration of nervous tissue within the central and peripheral nervous system (8). It seems that BM-MNC can facilitate recovery from SCI by promoting remyelinating spared white matter tracts or intensifying axonal growth (9). However, the transdifferentiation of BM cells into myelin cells is an area of great controversy, and there is no convulsive evidence that these cells do this process without extensive genetic and epigenetic manipulation.

Although the results of pre-clinical studies recommend that BM-MNCs could be used as a potential therapy for SCI, (10) they have not clearly indicated whether these cells have therapeutic advantages in SCI patients. Since BM-MNCs transplantation has been considered as a novel intervention in clinical trials for SCI, it has not been scientifically proven to be safe and effective. This systematic review investigates the clinical outcome of BM-MNCs transplantation for patients with traumatic SCI. The objective was to determine whether BM-MNC transplantation can increase ASIA scale,which is a valid and useful tool for determining the function maintained by a patient after suffering from spinal cord injuries (11).

Methods

Search Strategy

We performed PICOS framework (Determiningpatient, problem or population, intervention, comparison and outcome)to define the main concepts of the research questions.

Patient:People with Spinal Cord Injury

Intervention: Bone Marrow Transplantation

Comparison: No Treatment

Outcome:Improvement in the ASIA Score

Computerized databases were searched on 28 October 2012. To retrieve both original and secondary related studies, we used a sensitive librarian-assisted search strategy in the last available version of the three following databases at the time of the search: MEDLINE via Ovid SP (1948 to 28 October 2012), EMBASE via Ovid SP (1989 to 27 October 2012) and CENTRAL via Ovid SP (September 2012). The search was limited to the English language. Search was updated on May 2013; however, no new records were found. Because of the low number of results in the primary search, we applied a sensitive search strategy to retrieve a suitable number of records and minimize any missing of possible related records. Therefore, we included only problem and intervention in PICOS structure of the formulated question to achieve higher sensitivity, and we did not limit our results to humans and particular types of study designs. The database search was completed with a search of RCTs (Randomize Control Trials) registries and reviewing of the reference lists of the included studies along with citations. The following search strategy was developed for MEDLINE via Ovid SP and was then adapted to other resources:

I: Spinal Cord Injury

exp spinal cord injuries/

(((spinal or central or cervical or medulla$) adj3 cord) adj3 (trauma$ or injur$ or syndrome or lesion or compress$ or pinch$ or trans?sect$ or transect$ or lacerat$ or contus$)).tw,ot.

(spinaltrans?section).tw,ot.

(transverse lesion).tw,ot.

(autonom$ adj3 (dysreflexia$ or hyper?reflexia$)).tw,ot.

myelopath$.tw,ot.

(conusmedullaris syndrome).tw,ot.

or/1-7

II: Bone Marrow Transplantation

bone marrow transplantation/

bone marrow purging/

exp stem cell transplantation/ and (bone marrow).tw,ot.

((bone marrow) adj6 (transplant$ or graft$ or purg$ or (cell adj (transfer or remov$)) or rescu$ or transfus$)).tw,ot.

((((stem cell) or cord) adj (transplant$ or graft$ or purg$ therap$)) and (bone marrow)).tw,ot.

or/9-13

III: I and II

8 and 14

Inclusion criteria

All those clinical trials which measured neurological assessment as ASIA scale pre- and post-transplantation or those which included participants with traumatic SCI (cervical or thoracic level) as well as ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) scale A or B at baseline were included in this review.

Exclusion criteria

Animal studies were excluded in this review. Other studies that did not report ASIA score as a clinical outcome along with those studies which considered other types of bone marrow derived cells or mixed cell population (BM-MSCs + BM-MNCs) as well as case reports were excluded from this review.

Subgroups

This review determined three subgroups on the basis of impairment scale, level of injury and duration of SCI. The ICCP (International Campaign for Cures for spinal cord injury Paralysis) panel guideline mentioned that these variables can influence spontaneous recovery rate. However, a clinical trial considering ASIA -A patients showed less spontaneous improvement over time (18). This review analyzed patients with complete and incomplete ASIA separately. In addition, the duration of SCI in terms of acute and chronic injuries was defined, and the level of injury was divided into cervical and thoracic injury.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by two independent researchers of the study (M-Y and HR-A). Data pertaining to the number of the enrolled patients, injury types and levels, type and dose of cell transplants, duration of the follow ups and clinical outcomes with confidence intervals were extracted from the papers. We defined the percentage of the patient’s improvement from ASIA scale A to B/C or ASIA scale B to C/D as a clinical outcome after a one- year follow-up. It should be noted that a clinical trial with a small size effect may need a more accurate outcome measure such as a statistically mean change in the motor and sensory scores (19). Therefore, we reported the mean change of the motor score and sensory score (light touch and Pinprick) at the time of the transplant and at the end of the last follow-up as a functional outcome in three studies (10, 14, 16). These studies reported the details of motor and sensory scores along with the ASIA scale. The confidence interval and lower and upper limits were not reported directly, so we calculated and recorded them using other indices which were based on formulas.

Synthesis of the results

Meta-analysis was performed using the STATA statistical package version 11. First, we assessed the heterogeneity between the studies by Chi-squared test (P<0.1 as meaningful). We used random or fixed model for pooling the percentage of improvement and 95% confidence intervals in case of heterogeneous and homogenous cases, respectively. In addition, p-values less than 0.05 were regarded significant.

The subgroups were determined based on the patients’ injury type (impairment scale, level and stage of injury). ASIA-A, ASIA-B, cervical, thoracic and acute patients were regarded as subgroups. Chronic subgroups were excluded from the meta- analysis because this subgroup included only one study. Due to the different characteristics of each subgroup after excluding the chronic group from the analysis, we had to pool the data from the acute group separately, not acute versus chronic; otherwise, the pooled estimate would have led to an inability in reaching a firm conclusion about the potential benefit of a candidate therapy.

Results

Study selection

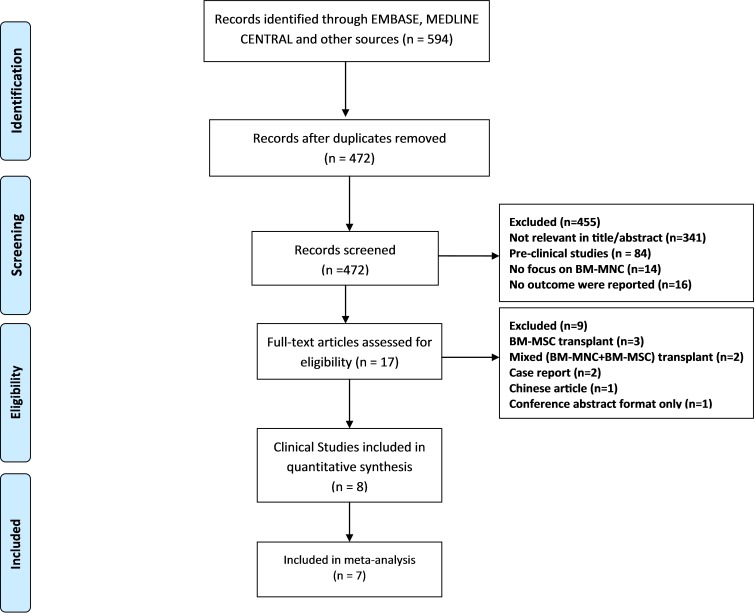

The search identified 594 studies, among which 122 were duplicates ( Fig. 1). Titles and abstracts of the obtained articles were assessed for relevancy by two researchers independently (M-Y, HR-A). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with the authors. After screening the titles and abstracts, 17 studies were determined as eligible (BM-MNC transplantation, in which the standard neurological outcome had been reported). The full texts of the relevant articles were checked for eligibility criteria after investigating the full reports, and consequently nine studies were excluded. Finally, eight studies with a total number of 337 participants were evaluated to find the outcome of BM-MNC transplant in patients with SCI (Table 1) (12–17).Moreover, seven studies were included in the meta- analysis.

Fig. 1 .

Flow of the Studies through the Review Process

Table 1 . Published BM-MNCs Transplantation Trials for SCI .

| Reference | Participant | Transplant | Percentage of the Patient in the Subgroup with Improved ASIA (%) | Functional Outcome | ||||||||

| First author | Number of cases | Sub groups |

Dosage BM-MNC *10⁶ |

All | A* | B** | C ʸ | T^ | Ac ʰ | Ch˅ | CG ʳ | Follow up |

| Attar et al,2011[12] | Patient = 4 Control= 0 |

All patients ASIA A, thoracic and acute. |

19.6-275 | 75 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 75 | 0 | - | 1 year Follow-up. 3 patient of 4 show neurological improvement and none of the patients suffered from any side effects or complications. |

| Deda et al,2009[13] | Patient = 9 Control = 0 | All patients ASIA A 6 cervical and3 thoracic, all patients chronic. | 20-67 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | - | 1 year Follow-up. All of the patients showed improved neurological function without any serious complications. |

| Geffner et al,2008[14] | Patient =6 Control= 0 | 5 patients ASIA A and 1 ASIA BAll thoracic, 4 acute and 2 chronic. | 400 | 83 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 83 | 75 | 100 | - | 1 year Follow-up. 7 patients of 8 show neurological improvement, all patients showed increased bladder control/sensation and had improved quality of life scores .no cases of tumorformation, infection, or increased pain. |

| JK Jung et al,2011[11] | Patient= 19 Control= 0 | 17 patient ASIA A and 2 patient ASIA B 10 patient cervical and 9 thoracic, all patients acute. | 200 | 47 | 52 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 47 | 0 | - | 3-11 month Follow-up. The ASIA scale of the group had improved in 7 patients from grade A to C, in 3 patients from grade A to B, and in 1 patient from B to C. |

| Kumar et al, 2009[15] | Patient= 240 Control= 0 | 233 patients ASIA A and 7 patients ASIA B 44 cervical and 196 thoracic and all chronic. | 1 | 31 | 31 | 42 | 34 | 31 | 0 | 31 | - | 3-21 month Follow-up. One-third of spinal cord injury patients had improved .motor and sensory change happened in 32.6% of patients. No complications or side effect were reported, except for minor reversible complaints. |

With respect to the quality assessment, all clinical trials had a high risk of bias; specifically, seven of eight studies were non-randomized. Moreover, the details of randomization methodswere unclear in the remaining studies. Since it is difficult to blind therapists to use stem cell transplant, none of the clinical trials reported allocation concealment or blinding. With regards to the incomplete data, all trials had a low risk of bias. Overall, two out of 337 patients failed to participate in the follow-up durations.

Meta analysis

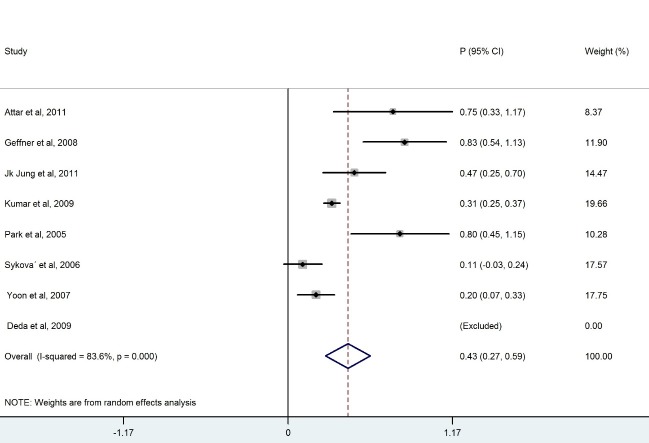

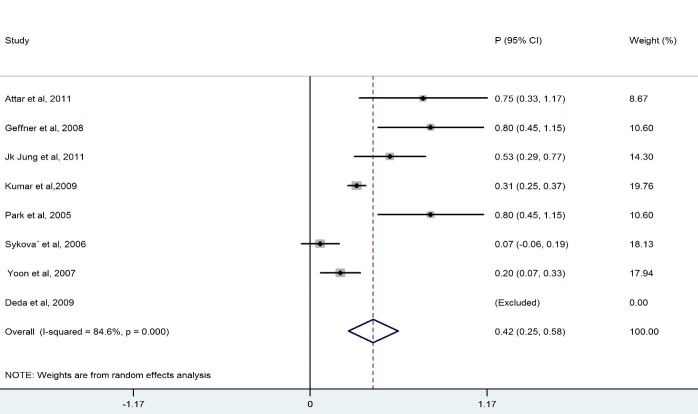

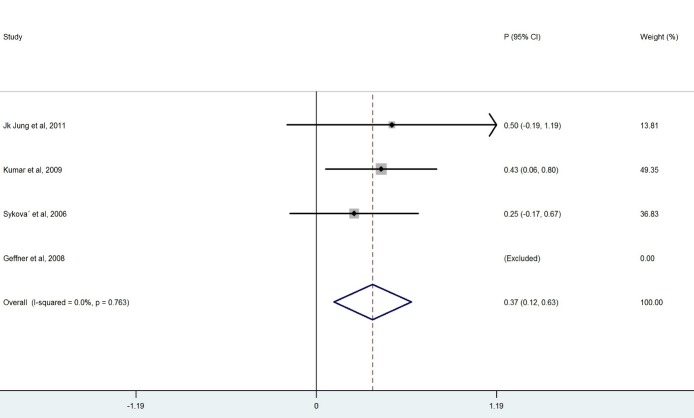

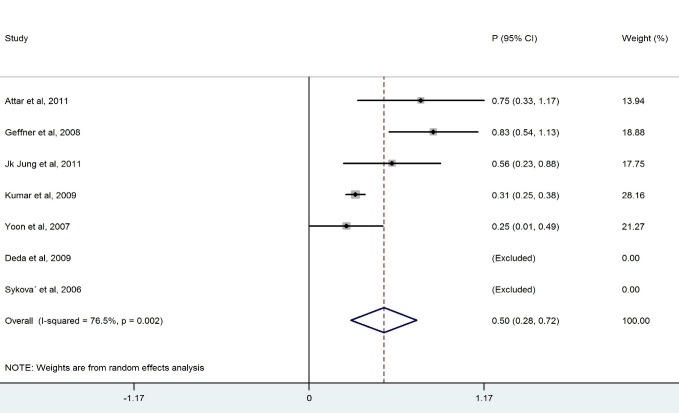

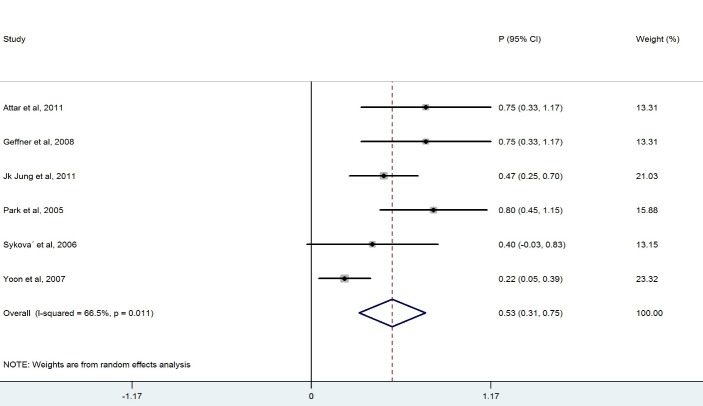

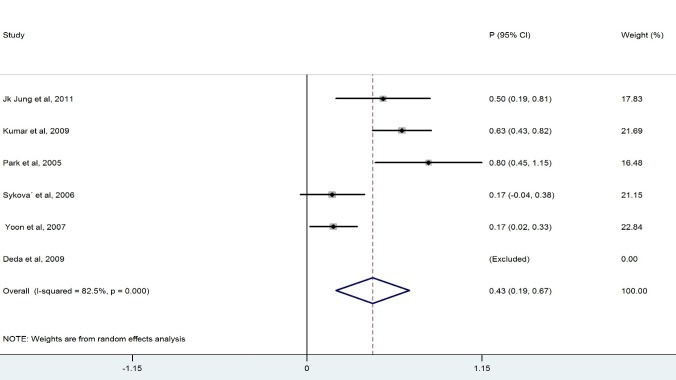

We ended up with eight studies in the systematic review, one of which was excluded from our analysis because of 100% improvement (No variation) (13). The remaining studies had a combined total of 328 patients. Our findings revealed a considerable heterogeneity among these studies (X2=36.1, p<0.0001, I2=83.6%). Also, the results of the meta- analysis using a random model revealed an estimate of 0.428 (95% CI = (0.268, 0.589)) for the proportion of the improvement which was statistically significant (p<0.0001). Although the meta- analysis in the subgroups of patients with BM-MNCs transplantation in ASIA-B at baseline resulted in homogeneity between the studies, a considerable heterogeneity was observed among them by considering ASIA-A, acute, cervical and thoracic subgroups of patients. Table 2 demonstrates the number of patients in each subgroup and the estimated pooled proportion of improvement as well as the results of heterogeneity tests. The meta- analysis revealed that the percentage of patient improvement (95% CIs) was 0.41 (0.25-0.58) for patients with ASIA scale A at the baseline, 0.37 (0.11-0.63) for patients with ASIA scale B at the baseline, 0.53 (0.31-0.74) for patients in acute stage, 0.43 (0.18-0.67) for patients with cervical injury level and 0.50(0.28-0.72) for patients with thoracic injury level.

Table 2 . Results of the Subgroups’ Meta- Analysis and Heterogeneity Tests .

| Subgroups | No. of Studies | No. of Patients | Heterogeneity | Pooled Estimate | ||||

| X2 | P-value | I2 | Proportion (95% CI) | P-value | ||||

| ASIA-A | 7 | 314 | 38.8 | <0.0001 | 84.6 | 0.419 (0.254, 0.585) | <0.0001 | |

| ASIA-B | 3 | 13 | 0.54 | 0.763 | 0 | 0.373 (0.115, 0.630) | <0.0001 | |

| Acute | 6 | 60 | 14.92 | 0.011 | 66.5 | 0.530 (0.313, 0.746) | <0.0001 | |

| Cervical | 5 | 94 | 22. 8 | <0.0001 | 82.5 | 0.432 (0.189, 0.674) | <0.0001 | |

| Thoracic | 5 | 227 | 17.04 | 0.002 | 76.5 | 0.501 (0.281, 0.722) | <0.0001 | |

X2: Heterogeneity chi-squared

I2: percentage of variation in the estimated proportion attributable to heterogeneity.

ASIA impairment scale in SCI clinical trial was considered as a clinical outcome. However, considering the functional outcome (motor and sensory scores) might also be useful in these trials. As a result of the mean change of the motor and sensory scores, three qualified studies conducted on 32 patients were assessed (Table 3). In the other trials, the details of the scores were not reported.

Table 3 . Mean Change of Motor and Sensory Score in 3 Clinical Trials .

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the clinical outcome of BM-MNCs transplant in SCI. The outcome measures were to obtain improvement in ASIA scale. The overall percentage of improvement between 328 patients was 43% .There was a considerable heterogeneity among these studies I2=83.6% ( Fig. 2). Meta- analysis was performed for each subgroup to achieve better results. Clinical outcome in patients who had ASIA scales A and B showed that the percentage of improvement in patients who had ASIA scale A at baseline (41%) was more than ASIA scale B(37%) (Table 2). Considerable differences between the number of patients in the subgroups of ASIA-A and ASIA-B might have led to this result because the likelihood of improvement in patients with incomplete impairment should be more than the complete functional impairment (19).In addition, there was homogeneity between the studies that included patients with ASIA-B at baseline in contrast with studies that included ASIA –A at baseline ( Figs. 3, 4).In comparison with the cervical and lumbar segment, cell transplantation in a thoracic segment might be less likely to affect a significant outcome. However, the potential risk of adverse effects which may result from the manipulation of cervical and lumbar spinal cord regions is higher. Therefore, a potential trial should weigh the advantages and risks of treating cervical versus thoracic injuries (18). Thoracic cases were includedfor safety concerns in most of phase I/II trials. The result of the meta-analysis revealed a considerable heterogeneity in both groups ( Figs. 6, 7). In addition, improvement in ASIA scale occurred in the patients with thoracic level (50%) more than cervical level (43%) (Table 2), and this may be due to the higher number of thoracic cases in this review. To assess the potentially beneficial effects of experimental treatments in SCI trials, mean changes in motor and sensory scores can be a more reliable efficacy index than the conversion of ASIA scale (21). In our review, just three out of eight studies (10, 14, 16) reported the details of ASIA motor and sensory scores. Although the percentage of patients with improved ASIA scores were 10% in one of these studies (16), the pooled mean change of motor, light touch and Pinprick scores in patients of this study significantly increased after intervention (Table 3). Another clinical trial assessed the quality of life score as Barthel Index. Geffner et al. (14) investigated different routes of transplant directly into the spinal cord, the spinal canal and intravenously and observed improvements in Barthel Index of all the patients. Considering the fact that the quality of life assessment in spinal cord injury is significant, it might be helpful to use this tool as a secondary outcome (19).The authors suggest that quality of life assessment be considered as a generic outcome for SCI cell transplantation trials. Only in one clinical trial a control group was included. In this trial, the intervention group demonstrated more improvement in ASIA scale than the control group. Yoon and colleagues (17) regarded 13 patients treated with conventional decompression and fusion surgery as the control group. In this trial, 20 % of the treatment group and 7 % of the control patients indicated an improved neurological function. Co-administration of granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has been applied in two studies. Yoon et al. (17) stated that the administration of GM-CSF for SCI patients may result in the progress of neurologic functions without any adverse effect. Recently, several researchers revealed that GM-CSF stimulates microglial cells to produce neurotrophic cytokines such as BDNF (22). In addition, Park and colleagues (20) believed that GM-CSF enhances the activity of the patients’ bone marrow and increases the number of BM derived stem cells in the circulating peripheral blood. However, GM-CSF administration induced fever, pain and leukocytosis in this trial. Regarding dynamic pathophysiological and multifactorial nature of SCI and its consequences, the success of future cell therapy might likely depend on the informed co-administration of combinatorial stem cell transplantation, pharmacological and rehabilitation therapies (4). This review demonstrated that BM-MNCs transplantation is a relatively safe intervention without serious adverse events.In comparison with mesenchymal stem cells or other cell types, BM-MNCs can be easily obtained and isolated in a short time just before transplantation and do not require in vitro expansion. This reduces processing costs and minimizes the risks of contamination (23).

Fig. 2 .

Forest Plot for Overall Percentage of Patient Improved ASIA Scale

Table 1 . Published BM-MNCs Transplantation Trials for SCI .

| Study | Participant | Transplant | Percentage of the Patients in the Subgroup with Improved ASIA (%) | Functional Outcome | ||||||||

| Reference | Include Patient | Treatment group |

Dosage BM-MNC *10⁶ |

All | A* | B** | C ʸ | T^ | Ac ʰ | Ch˅ | CG ʳ | Follow up |

| Park et al 2005[10] | Patient= 5 Control= 0 | All patients ASIA A cervical and acute. | 1980 | 80 | 80 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 80 | 0 | - | 6-18 month Follow-up. Five of the six patients showed improved neurological function .No serious complications, that is, increased mortality and morbidity were reported. |

|

Sykova et al,2006 [16] |

Patient = 19 Control= 0 | 15 patients ASIA A , 4 ASIA B ,12cervical and 8 thoracic , 5 acute 14 chronic | 5530 | 10 | 6 | 25 | 16 | 0 | 33 | 0 | - | 6-12 month Follow-up. 2 patients lost to follow-up and 2 of the 19 patients showed an improved ASIA score. No serious complications were reported. |

| Yoon et al 2007[17] | Patient= 35 Control= 13 | All patients ASIA A, 23 cervical and 12 thoracic, 23 acute and 12 chronic. |

200 |

20 | 20 | 0 | 17 | 25 | 21 | 0 | 7 | 10 month Follow-up.7 patients of 35 patients in transplant group and one of 13 patients in control group showed improved neurological function. No serious complications, sepsis, or wound infections were reported. |

A*= ASIA A patient, B**= ASIA B patient, C ʸ =Cervical level, T^= Thoracic Level, Ac ʰ= Acute, Ch˅=Chronic, CG ʳ=Control Group.

Fig. 3 .

Forest Plot for Overall Percentage of Patients with ASIA-A Improved ASIA Scale

Fig. 4 .

Forest Plot for Overall Percentage of Patients with ASIA-B Improved ASIA Scale

Fig. 6 .

Forest Plot for Overall Percentage of Cervical Patient Improved ASIA Scale

Fig. 7 .

Forest Plot for Overall Percentage of Thoracic Patient Improved ASIA Scale

Fig. 5 .

Forest Plot for Overall Percentage of Acute Patient Improved ASIA Scale

There were many restrictions in drawing a certain conclusion on the outcome of BM-MNCs transplantation in this review. As clinical trial in stem cell therapy is a new method and there is no sufficient literature on stem cell therapy due to the ethical issues and other limitations, we did not consider quality assessment and publication bias of the included studies in this analysis. The included trials in this review did not consider control groups or blinded assessments, and this might have led to an overestimation of the overall outcome (24). Although the quality assessment of the trial tools presented good correlation, the results of one study which evaluated the impact of quality assessment in the meta- analysis showed that in systematic reviews with the samedirection of effect, the quality assessment may not significantly change the results (25). Since most of the included studies in this review demonstrated some degrees of improvement, waiving the quality of trials may not cause significant changes.

Conclusion

BM-MNCs transplantation in spinal cord injury seems to be feasible, safe and have a good degree of outcome improvement. Although most of the studies showed promising results, more qualified randomized controlled trials should be conducted to examine the efficacy and appropriate dosage of BM-MNCs for patients with spinal cord injuries.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Manuela Joore and H.Van.Santbrink for their useful advices.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare they have no conflict of interests.

Cite this article as: Aghayan H.R, Arjmand B, Yaghoubi M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Kashani H, Shokraneh F. Clinical outcome of autologous mononuclear cells transplantation for spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2014 (14 October). Vol. 28:112.

References

- 1.Tator CH. Update on the pathophysiology and pathology of acute spinal cord injury. Brain Pathol. 1995;5(4):407–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojkovic M. Stem cells and spinal cord injury. Journal of the Serbian Society for Computational Mechanics. 2011;5(2):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vipond N, Zhang J. Stem cell Transplantation for Spinal Cord Injury. Evidence Based Healthcare Advisory Group. 2007:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fehlings MG, Vawda R. Cellular Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury: The Time is Right for Clinical Trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8(4):704–20. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regenberg AC, Hutchinson LA, Schanker B, Mathews DJ. Medicine on the Fringe: Stem Cell-Based Interventions in Advance of Evidence. Stem Cells. 2009;27(9):2312–9. doi: 10.1002/stem.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moazzami K, Majdzadeh R, Nedjat S. Local intramuscular transplantation of autologous mononuclear cells for critical lower limb ischaemia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011;12:Art. No.: CD008347. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008347.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cox Jr CS, Baumgartner JE, Harting MT, Worth LL, Walker PA, Shah SK. et al. Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy for severe traumatic brain injury in children. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(3):588–600. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318207734c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phinney DG, Isakova I. Plasticity and therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in the nervous system. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(10):1255–65. doi: 10.2174/1381612053507495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasari VR, Spomar DG, Cady C, Gujrati M, Rao JS, Dinh DH. Mesenchymal stem cells from rat bone marrow down regulate Caspase-3 mediated apoptotic pathway after spinal cord injury in rats. Neurochem Res. 2007;32(12):2080–93. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park HC, Shim YS, Ha Y. et al. Treatment of Complete Spinal Cord Injury Patients by Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Transplantation and Administration of Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(5-6):913–22. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung JK, Oh CH, Yoon SH, Ha Y, Park S, Choi B. Outcome Evaluation with Signal Activation of Functional MRI in Spinal Cord Injury. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50(3):209–15. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.50.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attar A, Ayten M, Ozdemir M. et al. An attempt to treat patients who have injured spinal cords with intralesional implantation of concentrated autologous bone marrow cells. Cytotherapy. 2011;13(1):54–60. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.510506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deda H, Inci MC, Kürekçi AE. et al. Treatment of chronic spinal cord injured patients with autologous bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: 1-year follow-up. Cytotherapy. 2008;10(6):565–74. doi: 10.1080/14653240802241797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geffner LF, Santacruz P, Izurieta M, Flor L. et al. Administration of Autologous Bone Marrow Stem Cells into Spinal Cord Injury Patients via Multiple Routes Is Safe and Improves Their Quality of Life: Comprehensive Case Studies. Cell Transplant. 2008;17(12):1277–93. doi: 10.3727/096368908787648074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar AA, Kumar SR, Narayanan R, Arul K, Baskaran M. Autologous Bone Marrow Derived Mononuclear Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury: A Phase I/II Clinical Safety and Primary Efficacy Data. Exp Clin Transplant. 2009;7(4):241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syková E, Homola A, Mazanec R. et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation in patients with subacute and chronic spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant. 2006;15(8-9):675–87. doi: 10.3727/000000006783464381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon SH, Shim YS, Park YH. et al. Complete Spinal Cord Injury Treatment Using Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Transplantation and Bone Marrow Stimulation with Granulocyte Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor: Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):2066–73. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW. et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP Panel: clinical trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(3):222–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A. et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(3):206–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katalinic OM, Harvey LA, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of stretch for the treatment and prevention of contractures in people with neurological conditions: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2011;91(1):11–24. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD. et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP Panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(3):190–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouhy D, Malgrange B, Multon S. et al. Delayed GM-CSF treatment stimulates axonal regeneration and functional recovery in paraplegic rats via an increased BDNF expression by endogenous macrophages. FASEB J. 2006;20(8):1239–41. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4382fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alvarez-Viejo M, Menendez-Menendez Y, Blanco-Gelaz M, Ferrero-Gutierrez A, Fernandez-Rodriguez M, Gala J, et al., editors. Quantifying Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Mononuclear Cell Fraction of Bone Marrow Samples Obtained for Cell Therapy. Transplantation proceedings; 2013: Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24. Moore A, McQuay H, Bandolier’s Little Book of Making Sense of the Medical Evidence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- 25.Carlos Rodrigues da Silva Filhoa. et al. Assessment of clinical trial quality and its impact on meta-analyses. Rev Saudepublica. 2005;39(6) doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102005000600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]