Abstract

Objectives

To determine the frequency and type of adverse events (AEs) associated with dental devices reported to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database.

Methods

We downloaded and thoroughly reviewed the dental device-related AEs reported to MAUDE from January 01, 1996 – December 31, 2011.

Results

MAUDE received a total of 1,978,056 reports between January 01, 1996 and December 31, 2011. Among these reports, 28,046 (1.4 percent) AEs reports were associated with dental devices. Within the dental AE reports that had event type information, 17,261 reported injuries, 7,777 reported device malfunctions, and 66 reported deaths. Among the 66 entries classified as death reports, 52 actually reported a death in the description; the remaining were either misclassified or lacked sufficient information in the report to determine whether a death had occurred. 53.5 percent of the dental device associated AEs pertained to endosseous implants.

Conclusion

There is a plethora of devices used in dental care, and to achieve Element 1 of AHRQ’s Patient Safety Initiative, we must be able to monitor the safety of dental devices. While MAUDE is essentially the single source of this valuable information, our investigations led us to conclude that it currently has major limitations that prevent it from being the broad-based patient safety sentinel the profession requires.

Practical Implications

As potential contributors to MAUDE, dental care teams play a key role in improving the profession’s access to information about the safety of dental devices.

Keywords: Dental Equipment, Dental Public Health, Dental Records, Informatics, Quality of Care, Safety Management

INTRODUCTION

Dental care demands the use of a dizzying range of devices: endodontic files, endosseous implants, orthodontic brackets, handpieces, and fluoride varnish, just to name a few. These items are essential to the practice of dentistry but are accompanied by the risk for adverse events (AEs), which the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines as “any undesirable experience associated with the use of a medical product in a patient” (1). To uphold our profession’s responsibility to provide the safest possible care to our patients, we must be vigilant and continually monitor the safety of dental devices and products, which by their very nature, expose our patients to risk. As we described in our previous paper (2), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has proposed a four-element patient safety initiative to minimize patient safety hazards. This model provides a useful framework for dentistry to “identify, understand, and reduce the risk of harm associated with medical errors and health care system–related problems.”(3) By continually updating the risks associated with dental devices, we as a profession reaffirm our commitment to Element 1 of the Patient Safety Initiative (3), Identifying Threats to Patient Safety.

The FDA, which regulates all medical devices and products in the United States, has a post market surveillance system to keep the track of device problems after a device has been brought to market. Here, it is useful to understand the definition of a device as compared to a drug: devices achieve their intended effect without a chemical interaction with or metabolism by the body (4). Thus, dental floss is a device, while lidocaine is a drug. For some devices, such as fluoride varnish, the distinction is subtler. Recalls of dental devices happen frequently. The recalls that have occurred in 2013 include an absorabable collagen wound dressing, which may have been manufactured with excess pyrogens (5); endodontic canal preparation instruments with incorrect length markings (6); and orthodontic bracket buccal tubes with incorrect labeling that might lead to unintentional rotation of the molars (7).

JADA publications from 2001 (8) and 2013 (9) nicely reviewed the background of FDA post-market device surveillance. What is salient for the work we present here is that the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database contains both individual voluntary reports from health care providers and consumers and individual mandatory reports from manufacturers and user facilities, dating back to August 1, 1996. Once manufactures or distributors become aware of device-related AEs like deaths, serious injury, or malfunctions, they are obligated to report the AE to the FDA within 30 days. Similarly, user facilities, described as “a hospital, an ambulatory surgical facility, a nursing home, an outpatient treatment facility, or an outpatient diagnostic facility which is not a physician’s office,” have 10 days to report the AE to the FDA (10). MAUDE contains a narrative description of the reported event, information about the occupations of the reporters, information about patient problems and device problems, and the results of manufacturers’ evaluations and conclusions about reported events.

Since its inception, MAUDE has received millions of reports, a number of which involve dental devices. The 2001 JADA publication on the FDA’s postmarket device surveillance (8) presented an analysis of the data collected from August 1996 through June 1999, which included reports of two deaths, 18,406 injuries, and 9,942 device malfunctions. These dental device reports represented 10.5% of all of the device reports during that timeframe. Endosseous implants represented the vast majority of all dental device reports at that time. The more recent 2013 JADA publication on FDA-post market surveillance focused primarily on drug-related reports and did not quantify the device reports, but at the same time, it reinforced the value of continual mining of the device-related AE reports (9). The device-related AEs uncovered through that work included detachment or fracture of dental needle components; osseointegration failure or loss of endosseous dental implants; and fracture, overheating or malfunction of dental instruments, e.g., high-speed handpieces.

Building upon these previous publications, we determined the frequency and type of dental AEs reported to FDA by reviewing reports submitted to MAUDE from January 01, 1996 – December 31, 2011. In so doing, we were able evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of MAUDE reports for identifying threats to dental patient safety.

OBJECTIVES

By quantifying the frequency and type of dental AEs reported into MAUDE since its inception, we aimed to update the dental profession’s understanding of device-related threats to dental patient safety, thereby contributing to Element 1 of AHRQ’s Patient Safety Initiative. In parallel, we evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of MAUDE as a source of device-related patient safety information. The importance of this undertaking is best understood in context: dentistry does not have the extensive patient safety literature that medicine has accumulated. In fact, it has been noted that there are few studies or reports related to errors or AEs that take place in dental practices (2, 11) This may be attributed to a number of causes: harm produced by dental devices may be less severe, follow-up is more difficult in a dispersed ambulatory setting, dentists may fear impact on remunerations, and there may be gaps in dentistry’s patient safety culture (2, 11).

METHODS

One can access the MAUDE data in two ways: (1) via an online search available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfMAUDE/search.CFM or (2) via downloading the data files from the FDA website (12). For our study, we included all the reports from January 01, 1996 through December 31, 2011. We used MYSQL database version 5.0.77 and MYSQL workbench version 5.2 to analyze the data. The MAUDE data can be broadly classified as master event data, patient data, device data and free-text data, all collected via the MedWatch forms described previously. Master event data includes reporting source and event type details, and text data contains textual information from the MedWatch. At the time of our search, there were 296 distinct dental product codes catalogued by MAUDE (13), which we used to create a dental products lookup table to identify the dental products contained within the database.

To better understand MAUDE reporting trends, we first identified and plotted the medical and dental device-associated reports from January 01, 1996 – December 31, 2011. We identified the number of mandatory and voluntary reports, as well as the reports related to death, injuries, and malfunctions, respectively. We also analyzed event locations and the reporters’ occupations. To determine dental devices that contributed to deaths, we further analyzed the death reports reported to FDA during our study period. We calculated the 20 dental devices most commonly associated with AEs, as well as the top 10 problems associated with dental devices. Finally, as we found that endossoeus implants were by far the highest-ranking device associated with AE reports, we also explored the top 10 endossoeus implant-related problems.

RESULTS

There were a total of 1,978,056 reports deposited into MAUDE from January 01, 1996 to December 31, 2011. 28,046 (1.41 percent) of these reports were associated with dental devices, 26,691 of which were mandatory (23,583 manufacturer’s reports, 2,968 distributor’s reports and 140 reports from the user facilities) and 1,355 were voluntary reports (see Table 1). Among the 28,046 dental device-associated reports, we found a total of 66 deaths, 17,261 injuries, and 7,777 device malfunctions (see Table 1). The balance of 2,942 reports did not provide any information about the event, reported the event to be “other,” or had invalid data as noted by FDA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Dental Adverse Events Reports found in MAUDE (N=28,046)

| Types of Reports | Mandatory Reports | 26,691 (95.2) |

| Manufacturer Report | 23,583 | |

| Distributor Report | 2968 | |

| User Facility Report | 140 | |

| Voluntary Reports | 1355 (4.8) | |

|

| ||

| AE Types | Injuries | 17,261 (61.5) |

| Malfunctions | 7777 (27.7) | |

| Other | 2630 (9.4) | |

| Invalid Data/No data | 312 (1.1) | |

| Death | 66 (0.23) | |

Of the 28,046 AEs reported, 17,387 (62.0%) were submitted by dentists: 8,994 of these reports were submitted by dentists to the manufacturers, 4,368 were submitted to the distributors, and 4,025 were submitted voluntarily to MAUDE by the dentists. A large number, 14.0%, of reports indicated the location as being “other,”, 6.6%, of reports left the location field blank, had either invalid data or location marked as “no information”, and 4.6% of reports had location marked as “not applicable.” The next most common reporters were physicians (4.4%). Other reporters included patients, dental assistants, dental hygienist, attorneys, biomedical engineers, physician assistants, radiologic technologists and patient family members or friends, among others (see Table 2). The categories we report are those maintained by the FDA. Very little specific information on event location was contained within the reports (see Table 3). 1.3% of the dental AEs occurred in a hospital.

Table 2.

Reporters of Dental Adverse Events found in MAUDE (N=28,046)

| Type of Reporter | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Dentist | 17,387 (62.0) |

| Other | 3917 (14.0) |

| Unknown/Invalid Data/Blank/No Information | 1860 (6.6) |

| Not Applicable | 1280 (4.6) |

| Physician | 1240 (4.4) |

| Patient | 863 (3.1) |

| Dental Assistant | 668 (2.4) |

| Attorney | 215 (0.8) |

| Nurse | 176 (0.6) |

| Risk Manager | 143 (0.5) |

| Other Health Care Professional | 134 (0.5) |

| Patient Family Member or Friend | 42 (0.1) |

| Health Professional | 30 (0.1) |

| Service Personnel | 16 (0.1) |

| Pharmacist | 15 (0.1) |

| Biomedical Engineer | 11 (0) |

| Physician Assistant | 11 (0) |

| Radiologic Technologist | 10 (0) |

| Dental Hygienist | 6 (0) |

| Other Caregiver | 5 (0) |

| Phlebotomist | 4 (0) |

| Medical Equipment Company Technician Representative | 3 (0) |

| Service and Testing Personnel | 3 (0) |

| Medical Technologist | 2 (0) |

| Respiratory Therapist | 2 (0) |

| Speech Therapist | 2 (0) |

| Medical Assistant | 1 (0) |

Table 3.

Location of dental adverse events as reported in MAUDE (N=28,046)

| Event Location | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Blank | 13097 (46.7) |

| Other | 6490 (23.1) |

| No Information/Invalid data/Not Applicable | 3589 (12.8) |

| Outpatient Treatment Facility | 3137 (11.2) |

| Unknown | 1036 (3.7) |

| Hospital | 367 (1.3) |

| Home | 240 (0.9) |

| Outpatient Diagnostic Facility | 54 (0.2) |

| Ambulatory Surgical Facility | 29 (0.1) |

| Nursing Home | 4 (0) |

| Public Venue | 2(0) |

| Clinic – Walk in, Other | 1(0) |

Annual MAUDE reporting trends

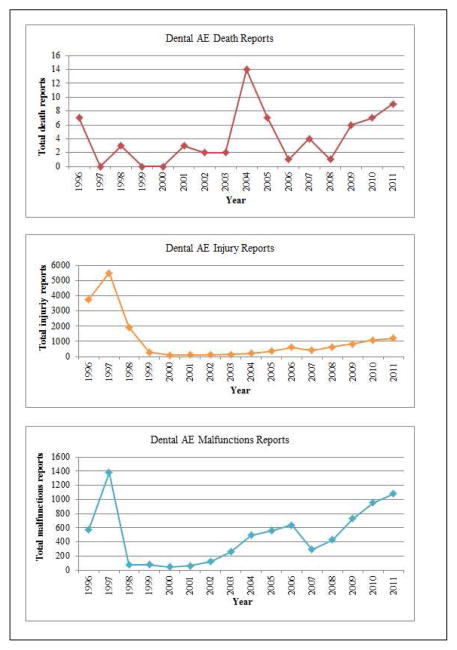

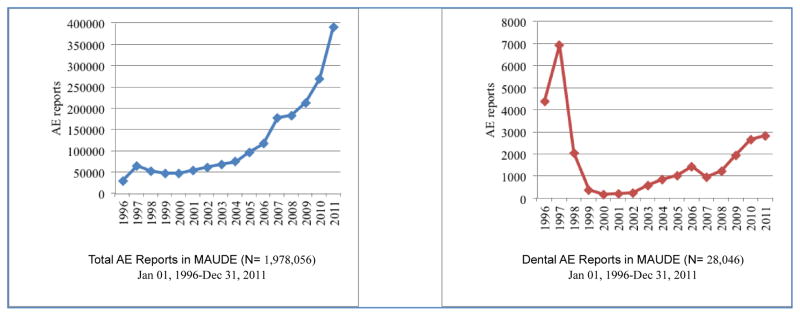

As MAUDE comprises both dental and non-dental, e.g., other medical, device-associated AE reports, we were interested to observe the respective reporting trends as shown in Figure 1. Both non-dental and dental AE reports experienced a local peak in 1997. The likely explanation for this spike is that a backlog of earlier events was reported: we contacted the FDA to seek an explanation and were told that the agency “cannot speculate on the reason that FDA received more AE reports in 1996–1997” (personal communication, February 10 2014). We then examined the death, injury, and malfunction dental device reporting trends, respectively (Figure 2). There were a total of 66 death reports associated with dental devices during the time range we considered. These reports peaked in 2004 (n = 14), which should be interpreted in light of the fact 2004 is the date of the report, rather than the date of death. There were no deaths reported between 1999 and 2000.

Figure 1.

Device-associated adverse event yearly reporting trends.

Figure 2.

Trends of reported deaths, injuries and malfunctions associated with dental devices

Detailed analysis of death reports

Upon further analysis of the 66 deaths reported, we found that 52 of the 66 reported deaths were confirmed deaths based on the information provided by the reporter, and the remaining were either misclassified or had insufficient information to determine whether a death had occurred in association with a dental device. An example of insufficient information is when the description contained no clear indication of patient death. Of the 52 confirmed deaths, 46 cases were from mandatory and 6 were from voluntary reports. In 23 reports, (11 males and 12 females), the gender was clearly mentioned in the description but the remaining 29 reports did not have any gender information. Seven of the 52 reports did not indicate a specific device associated with the death. Twenty-five of the 52 death reports described neurological damage associated with denture adhesives. The remainder of the death-associated devices were TMJ implants, denture cleansers, bone graft, distractor and dental implants. We should emphasize that this information is based solely on the MAUDE reports and does not constitute proof that a particular dental device caused a person’s death.

Dental devices associated with adverse events

The top 20 dental devices associated with AEs are shown in Table 4. By far, the most commonly represented devices were endosseous dental implants: 53.5 percent of the AE reports concerned these types of device. To put this in perspective, consider that the next most common device, denture adhesives, represented only 5.0 percent of the device-associated reports.

Table 4.

Top 20 devices associated with dental adverse events

| Device name | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| 1. Endosseous dental implant (Root Form) | 15267 (53.5) |

| 2. Ethylene oxide homopolymer and/or carboxymethylcellulose sodium denture adhesive | 1426 (5.0) |

| 3. Bone cutting instrument and accessories (Driver Wire And Bone Drill Manual) | 1278 (4.5) |

| 4. Dental Hand instrument (endodontic file) | 815 (2.9) |

| 5. Bone plate | 760 (2.7) |

| 6. Dental cement | 630 (2.2) |

| 7. Ultrasonic scaler | 565 (2.0) |

| 8. Dental hand piece and accessories | 523 (1.8) |

| 9. Total temporomandibular joint prosthesis | 505 (1.8) |

| 10. Intraoral dental drill | 458 (1.6) |

| 11. Carboxymethylcellulose sodium and/or polyvinyl methylether maleic acid calcium-sodium double salt denture adhesive | 455 (1.6) |

| 12. Dental injecting needle | 306 (1.1) |

| 13. Orthodontic appliance and accessories | 288 (1.0) |

| 14. Bone cutting instrument and accessories (Bone Drill Powered) | 283 (1.0) |

| 15. Intraoral source x-ray system | 252 (0.9) |

| 16. Intraoral devices for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea | 243 (0.9) |

| 17. Dental bur | 217 (0.8) |

| 18. Bone grafting material - synthetic | 209 (0.7) |

| 19. Bone grafting material with biologic component | 186 (0.7) |

| 20. Resin tooth bonding agent | 182 (0.6) |

Dental device events summary

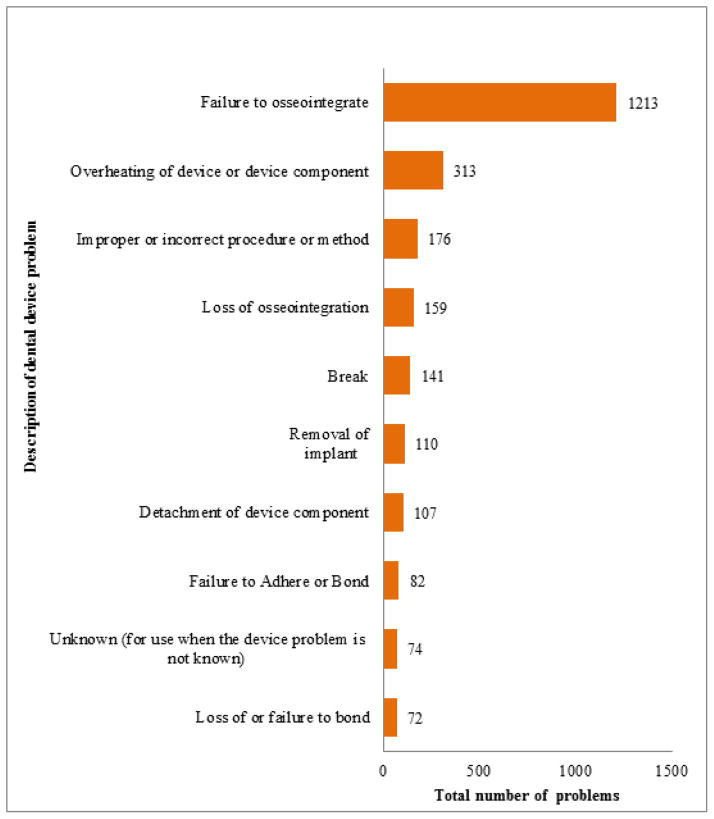

There were total of 3175 dental device-related problem descriptions reported to the FDA between January 1, 1996 through December 2011. The events were distributed across 129 different FDA-defined categories (14). Over a third, 1213 (38.2 percent) events concerned failure of dental implants to osseointegrate. The remaining top nine event categories are shown in Figure 3. It is notable that the ninth most common event category was “unknown.”

Figure 3.

Top 10 device problems associated with dental adverse events in MAUDE.

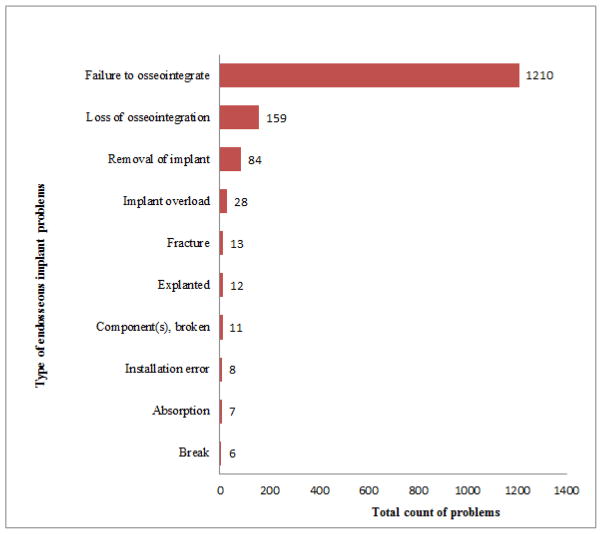

Endosseous implant associated events

As 53.5 percent of AEs concerned endosseous dental implants, we further analyzed the events described. We found that there were 27 different types of problems associated with endosseous implants, the most common of which (77.3%) was failure to osseointegrate, followed by loss of osseointegration and so on. Figure 4 contains the top 10 problems associated with endosseous dental implants.

Figure 4.

Top 10 endosseous implant related problems in MAUDE

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of threats to patient safety empowers our profession to protect our patients. Despite significant limitations, MAUDE is the only consolidated source of this knowledge about dental devices. As such, it serves not only as a safety sentinel but a reminder that dentistry, like medicine, is inherently, sometimes surprisingly, risky. The practice of dentistry is replete with obvious sources of risk, such as dental burs and needles, but sometimes, these risks lurk where we might least expect them. Consider the many reports to MAUDE associated with denture adhesives. At first glance, use of these products might not seem to be a fraught with peril, but as described in Denture cream: An unusual source of excess zinc, leading to hypocupremia and neurologic disease, published in the journal Neurology in 2008 (15), the zinc in some denture adhesives can lead to excess zinc ingestion if the adhesive is used beyond the recommended levels. In turn, high zinc levels can lead to copper deficiency, which is most commonly manifested through neurologic and hematologic disease. These findings were supported by additional publications (16, 17). In 2010, several manufacturers issued warnings and stopped or modified producing zinc-containing denture adhesives, but zinc-containing denture adhesives were not totally phased out. A 2013 publication in the American Journal of Stem Cells described pancytopenia, a reduction in the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, in a 34 year-old patient with a partial denture who used zinc-containing denture adhesive, which resolved with copper therapy and discontinuation of the denture adhesive (18). A prosthodontist in Baltimore captured the problem well when interviewed about the risks of denture adhesives, “ ‘In 30 years I’ve never seen a patient who had these [neurological] problems.’ On the other hand, he said, ‘Maybe I’ve missed it. Now we’re all looking for it.’” (19). Resources like MAUDE help us to amass and share our collective knowledge about potential, but perhaps unseen, risks to our patients. In some cases these incidents may have been encountered but not recognized or reported as an adverse event.

The importance of MAUDE as a source of knowledge about threats to patient safety should not obscure its limitations. The content of the reports is not extensively validated, there may be more than one report per event, and the severity of the event (apart from the extreme of death or injury) is not classified. Furthermore, from the data stored in MAUDE, we cannot infer a causal association between the dental devices and AEs. While MAUDE contains narrative reports that attempt to describe the incident, our initial analyses suggest that they are insufficient to determine the causes or factors contributing to a particular adverse event. In addition, the coded data relating to problems associated with endosseous dental implants, for example, are intriguing as they appear to suggest that many of the AEs may be due to technique or biological issues rather than directly attributable to the device. However, great caution is required to adequately interpret data derived from MAUDE. To best serve a healthcare system that continually learns how to prevent AEs, the event report should contain the results of root cause analysis, an approach used across a variety of industries to identify factors that contributed to an event. Importantly, such an analysis should be conducted near the time of the event by people with contextual knowledge, as root cause analysis “cannot be used on archival records with any degree of accuracy”(20).

Another significant limitation is that MAUDE appears to be an under-utilized resource: its contents are sparse relative to the size of the dental profession. According to Kaiser Family Foundation State Facts, as of November 2012, there were 195,941 professionally active dentists in the USA (21). MAUDE contains only 17,387 reports of dental device-associated AEs submitted by dentists from August 01, 1996 through December 31, 2011. It would be improbably optimistic to assume that these events represent the sum total of device-associated AEs in American dental practices. Indeed, as reported in a 2013 Journal of the American Dental Association publication authored by RR, EK, and MW, we found that 34% (95% confidence interval 22% – 48%) of randomly-selected patient charts from an academic dental center with both teaching and faculty practices contained at least one AE (22), a number of which were device-related, e.g., fractured removable partial denture, fractured implant. None of these were voluntarily reported to MAUDE by the clinic. There may be multiple reasons why dental device related AEs go unreported in MAUDE including lack of awareness and the inherent difficulty in submitting a voluntary reports. One approach to addressing this problem might be to incorporate semi-automated reporting into electronic health records, and another might include instituting mandatory reporting by dental clinics. There is local precedent for mandatory patient safety reporting: in 2006, the District of Columbia passed the Medical Malpractice Amendment Act in 2006, which included “mandatory adverse event reporting” (DC Code § 7-161 (2007) (23). Further D.C. Municipal regulation, title 17, chapter 42 [dentistry], § 4212.5 requires dentists to report to the District of Columbia Board of Dentistry any deaths, disabling incidents or hospitalizations caused by administration of local anesthesia or nitrous oxide (24).

Finally, MAUDE should not be used to evaluate rates of AEs or to compare AE rates across devices (25). Indeed, in addition to having potentially more than one report per event, there may be a reporting bias due to, for instance, the fact that endosseous implants are relatively expensive, leading dentists prefer to approach the manufacturer to replace failed implants, with the manufacturer, in turn, reporting the failure to MAUDE. Our results should be interpreted with this in mind, and readers should not conclude, for example, that endosseous dental implants are associated with more injuries than are dental burs because there are more MAUDE reports about dental implants than burs. This information contained in MAUDE serves as a starting point to explore device associated AEs, and would, of course, be useful in terms of tracking patient safety trends, but such surveillance would require a different approach to event ascertainment.

By design, MAUDE limits its purview to device-related events. Such a focus is of indisputable value to an agency concerned with regulating devices, but there exist a range of other threats to dental patient safety, as can be corroborated by a review of media reports, the literature, and other information sources. Consider, for example, cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw following dental extractions among patients who take oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis; this event, theoretically, would be reported to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)(26), which focuses on drug and therapeutic biologic products. Yet other sources of information about threats to dental patient safety may be gleaned from the literature and from media reports, e.g., (27, 28). Dental practices would likely be better served by a single source that consolidated a range of threats to patient safety, rather than having to consult various sources like FAERS, MAUDE, the scientific literature, and the media, with each dental practice having to conduct the search anew.

MAUDE is an important, if imperfect, contributor to our profession’s knowledge about threats to patient safety. As a group, we, the authors of this paper, are interesting in cataloguing threats to patient safety in fulfillment of Element 1 of AHRQ’s Patient Safety Initiative. Indeed, we are working to address this gap by creating a central repository to catalogue the range of AE types that occur in the dental office with the support of an R01 from the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research, entitled Developing a Patient Safety System for Dentistry (29). In so doing, we are drawing upon MAUDE reports associated with dental devices, as well as the scientific literature, the media, and information gleaned from our electronic health records. Those readers who are affiliated with a dental practice must also contribute to this effort by ensuring that well-documented reports of device-associated events are submitted to MAUDE.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DE022628.

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.What is a Serious Adverse Event? 2014 Jun 16; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/HowToReport/ucm053087.htm.

- 2.Ramoni RB, Walji MF, White J, Stewart D, Vaderhobli R, Simmons D, et al. From good to better: Toward a patient safety initiative in dentistry. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2012;143(9):956–60. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AHRQ’s Patient Safety Initiative: Building Foundations, Reducing Risk. Interim Report to the Senate Committee on Appropriations. 2003 December. Report No.: Contract No.: AHRQ Publication No. 04-RG005,.

- 4.Classification of Products as Drugs and Devices and Additional Product Classification Issues. 2014 Jun 15; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm258946.htm-_Toc294261432.

- 5.Class 2 Device Recall CollaPlug Absorbable Collagen Wound Dressing for Dental Surgery. 2014 Jun 15; Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfres/res.cfm?id=117050.

- 6.Class 2 Device Recall Lightspeed LSX Files. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfRES/res.cfm?id=115470.

- 7.Class 2 Device Recall Bracket Buccal Tube. 2014 Jun 15; Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfRES/res.cfm?id=116926.

- 8.Fuller J, Parmentier C. Dental device-associated problems: an analysis of FDA postmarket surveillance data. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2001;132(11):1540–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zavras AI, Rosenberg GE, Danielson JD, Cartsos VM. Adverse drug and device reactions in the oral cavity: surveillance and reporting. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2013;144(9):1014–21. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe N, Scott W. Medical Device Reporting for User Facilities. 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perea-Perez B, Santiago-Saez A, Garcia-Marin F, Labajo-Gonzalez E, Villa-Vigil A. Patient safety in dentistry: dental care risk management plan. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2011;16(6):e805–9. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience Database - (MAUDE) 2013 Jan 28; doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001948. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/PostmarketRequirements/ReportingAdverseEvents/ucm127891.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Product Classification. 2013 Jan 28; Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPCD/classification.cfm?start_search=1&Submission_Type_ID=&DeviceName=&ProductCode=&DeviceClass=&ThirdParty=&Panel=DE&RegulationNumber=&PAGENUM=500&SortColumn=DeviceClassDESC.

- 14.Device Problem Code Disposition File. 2014 Jun 16; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/PostmarketRequirements/ReportingAdverseEvents/EventProblemCodes/UCM134774.xls.

- 15.Nations SP, Boyer PJ, Love LA, Burritt MF, Butz JA, Wolfe GI, et al. Denture cream: an unusual source of excess zinc, leading to hypocupremia and neurologic disease. Neurology. 2008;71(9):639–43. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312375.79881.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedera P, Peltier A, Fink JK, Wilcock S, London Z, Brewer GJ. Myelopolyneuropathy and pancytopenia due to copper deficiency and high zinc levels of unknown origin II. The denture cream is a primary source of excessive zinc. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30(6):996–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Carvalho RM, Pashley DH. Hyperzincemia from ingestion of denture adhesives. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 2010;103(6):380–3. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khimani F, Livengood R, Esan O, Vos JA, Abhyankar V, Gutmann L, et al. Pancytopenia related to dental adhesive in a young patient. American journal of stem cells. 2013;2(2):132–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roylance F. Denture adhesives can cause zinc overdose, study says. Available from: http://phys.org/news/2011-04-denture-adhesives-zinc-overdose.html.

- 20.Battles JB, Lilford RJ. Organizing patient safety research to identify risks and hazards. Quality & safety in health care. 2003;12(Suppl 2):ii2–7. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser Family Foundation. State Facts: Professionally Active Dentists. 2012 Nov; Available from: http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparetable.jsp?ind=442&cat=8&sub=104&yr=279&typ=1&sort=a.

- 22.Kalenderian E, Walji MF, Tavares A, Ramoni RB. An adverse event trigger tool in dentistry: a new methodology for measuring harm in the dental office. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2013;144(7):808–14. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Interim Guidelines Issued for Medical Malpractice Amendment Act of 2006. Available from: http://newsroom.dc.gov/show.aspx/agency/hpla/section/2/release/11408.

- 24.District of Columbia Municipal regulations for dentistry. 2013 Feb 19; Available from: http://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/Dentistry_DC_Municipal_Regulations_for_Dentistry.pdf.

- 25.Gurtcheff SE. Introduction to the MAUDE database. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;51(1):120–3. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318161e657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Available from: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/surveillance/adversedrugeffects/default.htm.

- 27.Sedatives Cited in Toddler’s Dentist Office Death. Available from: http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/sedatives-cited-toddlers-dentist-office-death-n59156.

- 28.Hawthorne J, Stein P, Aulisio M, Humphries L, Martin C. Opiate overdose in an adolescent after a dental procedure: a case report. General dentistry. 2011;59(2):e46–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DEVELOPING A PATIENT SAFETY SYSTEM FOR DENTISTRY. 2015 Jun 16; Available from: http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=8588913&icde=19506063&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=1&csb=default&cs=ASC.