Abstract

In Arabidopsis, floral stem cells are maintained only at the initial stages of flower development, and they are terminated at a specific time to ensure proper development of the reproductive organs. Floral stem cell termination is a dynamic and multi-step process involving many transcription factors, chromatin remodeling factors and signaling pathways. In this review, we discuss the mechanisms involved in floral stem cell maintenance and termination, highlighting the interplay between transcriptional regulation and epigenetic machinery in the control of specific floral developmental genes. In addition, we discuss additional factors involved in floral stem cell regulation, with the goal of untangling the complexity of the floral stem cell regulatory network.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, floral meristem, stem cell, determinacy, flower development

Introduction

The flower is an elegant structure produced by angiosperms for effective reproduction. In Arabidopsis, floral organs are built in four whorls of concentric circles. From outermost to innermost, they consist of four sepals, four petals, six stamens and two fused carpels. The molecular mechanism specifying the identity of each whorl of floral organs is explained by the genetic ABCE model (Krizek and Fletcher, 2005). All four whorls of floral organs are derived from a self-sustaining stem cell pool named the floral meristem (FM), which arises from the peripheral regions of the shoot apical meristem (SAM). Much like the stem cells in the SAM, the stem cells in the FM are maintained by a signaling pathway involving the homeodomain protein WUSCHEL (WUS) and the CLAVATA (CLV) ligand-receptor system (Fletcher et al., 1999; Brand et al., 2000; Schoof et al., 2000). WUS is expressed in the organizing center, and it specifies and maintains the stem cell identity of the overlying cells. Expansion of WUS expression is prevented by the CLV signaling pathway, in which the CLV3 peptide is transcriptionally induced by WUS in the stem cells (Yadav et al., 2011; Daum et al., 2014). Due to the negative feedback regulatory loop of CLV3 and WUS, the stem cell pool remains constant in the initial floral developmental stages (stage 1~2) (Smyth et al., 1990; Schoof et al., 2000).

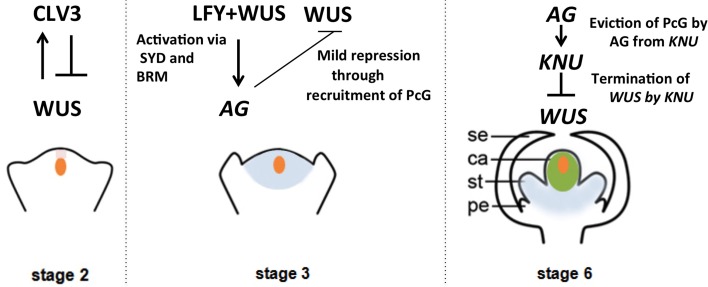

In the stage 3 floral bud, the C class gene AGAMOUS (AG) is induced by LEAFY (LFY) together with WUS in whorls 3 and 4 (Lenhard et al., 2001; Lohmann et al., 2001). AG has two major roles. It specifies reproductive organs, and it also regulates floral stem cell activity (Lenhard et al., 2001; Lohmann et al., 2001). In stage 6, floral stem cells are terminated in an AG-dependent manner to ensure proper development of the carpels. With respect to floral stem cell regulation, the major two pathways, the AG-WUS pathway and the CLV-WUS pathway, seem to function independently. The double mutant ag clv1 shows an additive phenotype of ag and clv1, and it expresses WUS in a broader domain than the ag mutant flower (Lohmann et al., 2001). In fact, the CLV-WUS pathway regulates floral stem cells spatially to restrict and maintain the stem cell pool in the early floral stages (stage 1–6), whereas the AG-WUS pathway provides temporal regulation to shut off stem cell activity at floral stage 6 (Figure 1). The precise timing of WUS repression is a key factor that determines the number of cells produced for reproductive organ development.

Figure 1.

Regulation of the timing of floral stem cell termination. Signaling cascades, transcriptional regulation and epigenetic regulation of the key proteins involved in floral meristem regulation are illustrated in a stage-specific manner. Orange indicates the domain of WUS expression, and pink, blue and green indicate the expression domains of CLV3, AG, and KNU, respectively.

Direct and indirect roles of AG in WUS repression

AG is reported to directly bind to the WUS locus to repress WUS expression (Liu et al., 2011). Based on an ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis screening of enhancer mutants of a weak allele, ag-10, which has only a moderate effect on floral meristem determinacy, one CURLY LEAF (CLF) mutant allele, clf-47, was identified (Liu et al., 2011). This suggests that CLF is required for floral meristem determinacy. CLF is a core component of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which suggests that WUS repression is associated with the deposition of the repressive mark H3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3), a mark that is mediated by the polycomb group proteins (PcG). Consistent with this, one mutant allele of TERMINAL FLOWER 2 (TFL2), a PRC1 factor in Arabidopsis, can enhance the ag-10 indeterminate phenotype (Liu et al., 2011). The ag-10 tfl2-2 double mutant flowers show enlarged carpels bearing ectopic internal organs, as observed in ag-10 clf-47. These results indicate that WUS is a target of PcG during flower development. AG binds to the two CArG boxes in the WUS 3′ non-coding region, and TFL2 occupancy at WUS is largely compromised in the ag-1 null mutant background. These results suggest that AG has a role in the recruitment of PcG to repress WUS. However, whether AG recruits PcG directly is still an open question.

35S::AG transgenic plants do not show any obvious floral meristem defects (Mizukami and Ma, 1997), and WUS is only mildly repressed after stage 3 directly by AG. For the termination of WUS at floral stage 6, a C2H2 zinc finger repressor protein, KNUCKLES (KNU), plays a pivotal role (Payne et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2009). KNU expression starts in stage 5–6, and mutation of KNU leads to enlarged carpels and repeated ectopic growth of stamens and carpels. This indeterminate floral phenotype is caused by the prolonged activity of WUS, showing that KNU is necessary for floral stem cell termination. KNU is directly induced by AG, and mutations in three CArG box sequences on the KNU promoter can abolish KNU induction (Sun et al., 2009). Timed induction of KNU by AG in stage 6 of flower development ensures floral meristem termination and proper development of the female reproductive organs. The timing of KNU expression is important for balancing floral stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Delayed KNU expression leads to indeterminate flowers with more stamens, and ectopic KNU activity can terminate floral meristem precociously and produce flowers without carpels. KNU is also regulated by PcG-mediated H3K27me3, and the removal of the repressive marks of H3K27me3 is AG-dependent. It takes approximately 2 days for AG to induce KNU in stage 6. During these 2 days, the H3K27me3 level on the KNU locus is progressively reduced, revealing a potential link between the transcriptional activation of KNU by AG and AG-dependent removal of H3K27me3 from the KNU chromatin (Sun et al., 2009).

Epigenetic regulation of termination timing in floral stem cells

In floral meristems, cell division take 1–2 days on average (Reddy et al., 2004). Therefore, the 2-day of delay in KNU induction corresponds to 1–2 rounds of cell division. Through cell division, the pre-existing H3K27me3 on the KNU locus may be passively diluted by incorporation of unmodified histone H3, enabling KNU expression (Sun et al., 2014). The core components of PcG, FIE and EMF2 are associated with specific promoter regions of KNU, which include the binding sites of AG. Indeed, this region contains a 153 bp fragment that is the minimal sequence of a functional polycomb response element (PRE). This sequence is both necessary and sufficient for PcG-mediated silencing of a ubiquitous promoter. This raises the possibility that AG plays a role in removing PcG to activate KNU. By simulating AG's physical blocking of the site with an artificially-designed TAL protein (a effector-based synthetic DNA binding protein designed to recognize the sequences around the first AG binding site), we showed that a YFP reporter could be activated in a cell cycle-dependent manner, even though it had been silenced by the minimal PRE sequence.

PRE was first identified in the fruit fly Drosophila, and it is targeted by the Pho-repressive complex (PhoRC) (Muller and Kassis, 2006). In Arabidopsis, homologs of PhoRC have not been identified, but in a genome-wide analysis of FIE binding sites, GA-repeat motifs appeared frequently, much like the Drosophila PRE (Deng et al., 2013). The KNU PRE is located near the 1kb upstream promoter region of the KNU transcriptional start site (Sun et al., 2014). Although the entire KNU locus is found to be bound by FIE and EMF2, only the transcribed region is covered by the repressive mark H3K27me3, and the PRE is not covered by the repressive mark. The indispensable role of the KNU PRE in recruiting PRC2 and establishing the FIE and EMF2 binding pattern on KNU indicates that PcG is first recruited to the KNU PRE and may later act on the KNU transcribed region to establish the H3K27me3 marks by sliding or by DNA looping. When the AG protein binds to the CArG box sequences that overlap the KNU PRE, the occupancy of AG triggers the displacement of PRC2, which leads to the loss of the H3K27me3 marks on KNU. Through cell division, H3K27me3 is diluted due to the lack of PcG activity, and KNU become de-repressed. Delayed reporter induction has been reported following artificial removal of a PRE by a cre-lox system in Drosophila, supporting this model of KNU de-repression (Beuchle et al., 2001; Muller et al., 2002).

Alternatively, the H3K27me3 mark can be erased by the JmjC-domain-containing histone demethylases REF6, EFL6, JMJ30 and JMJ32 (Lu et al., 2011; Crevillen et al., 2014; Gan et al., 2014). It has been reported that AG, REF6 and some other MADS-domain proteins may form a large protein complex whose function has not been characterized (Smaczniak et al., 2012). Therefore, it is also possible that, in parallel with H3K27me3 passive dilution, AG may recruit REF6 to the KNU promoter to actively remove H3K27me3. However, this hypothesis does not explain why cell cycle progression is required for AG to induce KNU. Also, the known mutants for these demethylases show no meristematic defects. Hence, we propose that REF6 might be involved in the regulation of some other direct downstream targets that are induced by AG.

To remove H3K27me3 marks and activate gene expression, other transcription factors or chromatin remodeling factors may perform functions similar to those that AG does. One such example is LFY in the control of the AG locus. For AG expression, the repressive mark H3K27me3 is removed by LEAFY (LFY), which recruits the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factors SPLAYED (SYD) and BRAHMA (BRM) on the AG second intron (Wu et al., 2012). Notably, GA-repeat motifs located near PREs are enriched at LFY targets (Wu et al., 2012; Zhang, 2014).

WUS, which is required in the organizing center to stimulate the maintenance of stem cell properties in the overlying cells (Yadav et al., 2011; Daum et al., 2014), is negatively regulated by PcG-mediated H3K27me3 (Zhang et al., 2007). In the SAM, the WUS-CLV signaling pathway works to maintain an appropriately sized stem cell. The signaling pathway remains active in floral stem cells and works to maintain their identity. It is interesting that WUS is re-activated and the signaling pathway is re-established in the stage 1 floral primordia (Mayer et al., 1998) and that the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factor SYD plays an important role in WUS activation (Wagner and Meyerowitz, 2002; Kwon et al., 2005). In floral stage 6, WUS is terminated by KNU and later silenced by PcG-mediated H3K27me3 marks (Sun et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2011). Because transcriptional repression of WUS and epigenetic silencing of WUS both occur at floral stage 6, we suggest that the transcriptional repressor KNU may integrate the two processes. During reproductive development, WUS is activated in developing stamens at stages 7-8, and later it is activated in developing ovules (Gross-Hardt et al., 2002; Deyhle et al., 2007). How the repressive mark H3K27me3 is removed from the WUS locus in those specific tissues and cell types is another open question that will require further investigation.

Other factors involved in floral meristem regulation

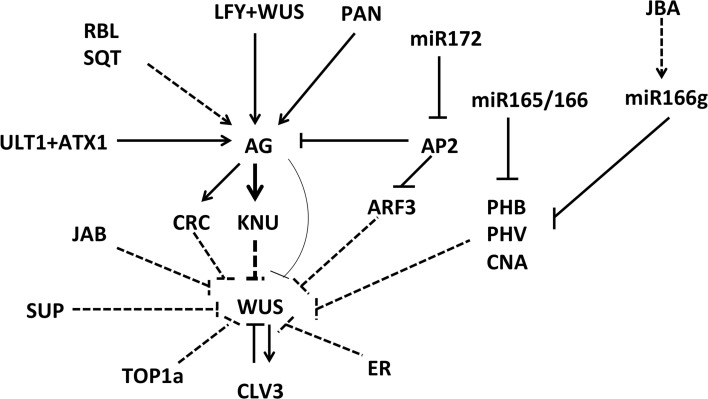

In addition to the known CLV-WUS signaling pathway that is responsible for the spatial maintenance of the floral stem cell niche, and in addition to the AG-KNU-WUS pathway for the timed termination of floral stem cells, other factors are known to be required for fine-tuning floral stem cell activities (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Various factors involved in floral meristem control. Many regulators control the expression of the stem cell identity gene WUS in direct and indirect ways. Solid lines indicate direct activation or repression, and dashed lines indicate a proposed type of regulation that has yet to be confirmed.

ULTRAPETALA1 (ULT1), a SAND domain containing protein (Carles and Fletcher, 2009), functions to induce AG in floral stem cells in an LFY-independent manner (Engelhorn et al., 2014). ULT1 may negatively regulate floral stem cell proliferation. The ult1 mutant flowers have bigger floral meristems and prolonged WUS activity, resulting in five petals instead of the usual four (Fletcher, 2001). Thus, both genetic and molecular studies indicate that ULT1 negatively regulates the WUS expressing domain in floral buds, potentially through the AG-WUS regulatory pathway (Carles et al., 2004). ULT1 is reported be a trithorax group (trxG) protein that can physically interact with another trxG protein, ATX1, a H3K4me3 methyltransferase (Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2003; Carles and Fletcher, 2009). By binding directly to AG regulatory sequences, ULT1 may recruit ATX1 to actively modulate the methylation status of nucleosomes at the AG locus.

Two other factors, REBELOTE (RBL) and SQUINT (SQN), can redundantly regulate floral stem cells in addition to ULT1 (Prunet et al., 2008). Reiterative reproductive floral organs are observed in flowers of the double mutants rbl sqn, rbl ult1, and sqn ult1. In the double mutant flowers, WUS activity is prolonged. Presumably, RBL and SQN both regulate the floral meristem by reinforcing AG expression. As a cyclophilin protein, SQN was recently found to bind the protein chaperone Hsp90 and promote microRNA activity via AGO1 (Earley and Poethig, 2011). The sqn single mutant displays increased carpel number relative to wild-type, and it has abnormal phyllotaxy of the flowers. This phenotype increased expression of SPL family transcription factors, which are targeted by the microRNA miR156 (Smith et al., 2009). PERIANTHIA (PAN), a bZIP transcription factor, also affects floral stem cell activity through direct activation of AG (Running and Meyerowitz, 1996; Chuang et al., 1999; Das et al., 2009; Maier et al., 2009). In pan mutant flowers, AG mRNA levels are reduced in short-day conditions, resulting in flowers with an increased number of floral organs. In addition, increased floral meristem indeterminacy is observed in lfy pan and seuss (seu) pan double mutant flowers. Ectopic floral organs continue to grow inside the fourth whorl floral organs of lfy pan and seu pan plants, suggesting a potential effect of the floral identity gene LFY and the adaptor-like transcriptional repressor SEU in floral meristem regulation (Das et al., 2009; Wynn et al., 2014).

SUPERMAN (SUP), which encodes a C2H2 zinc finger protein with a C-terminal EAR-like repression motif, is thought to function as a transcriptional repressor during flower development (Hiratsu et al., 2002). Loss-of-function mutants of SUP produce supernumerary stamens at the expense of carpels, indicating that SUP has a role in maintaining the boundary between the 3rd and 4th whorl floral organs (Sakai et al., 1995). Compared to the ag-1 mutant flowers, flowers of the double mutant ag-1 sup produce greatly enlarged floral meristems, generating reiterating whorls of petals, indicating the role of SUP in floral stem cell regulation in parallel with AG (Bowman et al., 1992).

CRABS CLAW (CRC), which is a direct downstream target of AG, is reported to be involved in floral meristem control. Null mutants for crc-1 do not show floral meristem defects; instead, the apical part of the mutant carpel is unfused. However, in combination with certain other mutants, supernumerary whorls of floral organs are observed; this occurs in crc-1 spatula-2, crc-1 ag-1/+, crc-1 rbl-1, crc-1 sqn-4, crc-1 ult1-4, crc-1 pan-3 and crc-1 jaiba double mutant flowers (Prunet et al., 2008; Zuniga-Mayo et al., 2012). CRC encodes a YABBY family transcription factor, and its expression begins in floral stage 5-6 on the abaxial side of the carpel primordia. CRC may regulate WUS activity in a non-cell autonomous manner (Bowman and Smyth, 1999; Lee et al., 2005).

Various microRNAs are reported to be involved in floral meristem determinacy control. For instance, miR172 promotes termination of floral stem cells by reducing the expression of its target, AP2 (Chen, 2004). Over-expression of a miR172-resistant version of AP2 (35S::AP2m1/3) leads to indeterminate stamens and petals (Chen, 2004; Zhao et al., 2007). The class III HD-ZIP genes, including PHABULOSA (PHB) and PHAVOLUTA (PHV), are targeted by miR165/166. Over-expression of miR165/166 in an ag-10 background, a weak allele of ag, or alleles of PHB and PHV that are resistant to miR165/166 can lead to indeterminate growth of floral organs (Ji et al., 2011). A proper balance of PHB/PHV and mir165/166 is important for floral meristem determinacy control. Consistent with this, in the triple mutant of phb phv cna, floral carpel number is increased (Prigge et al., 2005). Similarly, enlarged shoot meristems caused by increased WUS expression are observed in the jabba1-D mutant, a dominant allele of JABBA (JBA) that produces an increased amount of miR166g to regulate PHB, PHV and CORONA (CNA) expression (Williams et al., 2005).

The ERECTA (ER) receptor kinase-mediated regulation of WUS expression was recently reported to be mediated by a pathway parallel to the WUS-CLV pathway in both SAM and FM (Mandel et al., 2014). As a secondary signaling factor, ER works together with the nuclear protein JBA to repress WUS. In a jba-1D/+ er-20 double mutant background, the SAM and floral meristem are greatly enlarged, and the spiral vegetative phyllotaxy switches to whorled patterns. In the jba-1D/+ er-20 background, AG is ectopically expressed at a level that produces ectopic fused carpels from the inflorescence meristem, indicating an indirect role of ER in floral meristem identity control.

Recently, a mutation in the DNA topoisomerase gene TOPOISOMERASE1a (TOP1a) was shown to increase floral meristem indeterminacy in an ag-10 background, as the ag-10 top1a-2 double mutant exhibits an indeterminate floral meristem (Liu et al., 2014a). In floral stem cell regulation, TOP1a may function to reduce nucleosome density, thus facilitating PcG-mediated H3K27me3 deposition on WUS. Mutations in another gene AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 3 (ARF3), have also been reported to enhance the ag-10 indeterminate phenotype (Liu et al., 2014b). Double mutant ag-10 arf3-29 flowers produce additional floral organs that grow inside of the unfused sepaloid carpels, suggesting that ARF3 may reinforce floral meristem determinacy through WUS repression. The ARF3 locus is directly bound by AP2, indicating that AP2's role in floral stem cell regulation is also partially mediated by ARF3.

Conclusion

The complex regulatory network controlling floral meristem development produces elegant flowers with defined numbers and whorls of floral organs, thus ensuring that plant reproduction can occur (Figure 2). With knowledge of the spatial and temporal control of floral stem cells, as well as knowledge of the many factors responsible for fine-tuning floral stem cell activity, steady progress will be made in unraveling the mysteries of floral meristem regulation. Recently developed techniques, including ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, TALENs, CRISPR/Cas9, confocal live imaging and mathematical modeling, will help to provide further insights into the intriguing nature of flower development.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize for references not cited because of space limitations. This work was supported by research grants to Toshiro Ito from Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory (TLL).

References

- Alvarez-Venegas R., Pien S., Sadder M., Witmer X., Grossniklaus U., Avramova Z. (2003). ATX-1, an Arabidopsis homolog of trithorax, activates flower homeotic genes. Curr. Biol. 13, 627–637. 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00243-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuchle D., Struhl G., Muller J. (2001). Polycomb group proteins and heritable silencing of Drosophila Hox genes. Development 128, 993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. L., Sakai H., Jack T., Weigel D., Mayer U., Meyerowitz E. M. (1992). SUPERMAN, a regulator of floral homeotic genes in Arabidopsis. Development 114, 599–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. L., Smyth D. R. (1999). CRABS CLAW, a gene that regulates carpel and nectary development in Arabidopsis, encodes a novel protein with zinc finger and helix-loop-helix domains. Development 126, 2387–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand U., Fletcher J. C., Hobe M., Meyerowitz E. M., Simon R. (2000). Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science 289, 617–619. 10.1126/science.289.5479.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carles C. C., Fletcher J. C. (2009). The SAND domain protein ULTRAPETALA1 acts as a trithorax group factor to regulate cell fate in plants. Genes Dev. 23, 2723–2728. 10.1101/gad.1812609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carles C. C., Lertpiriyapong K., Reville K., Fletcher J. C. (2004). The ULTRAPETALA1 gene functions early in Arabidopsis development to restrict shoot apical meristem activity and acts through WUSCHEL to regulate floral meristem determinacy. Genetics 167, 1893–1903. 10.1534/genetics.104.028787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. (2004). A microRNA as a translational repressor of APETALA2 in Arabidopsis flower development. Science 303, 2022–2025. 10.1126/science.1088060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C. F., Running M. P., Williams R. W., Meyerowitz E. M. (1999). The PERIANTHIA gene encodes a bZIP protein involved in the determination of floral organ number in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 13, 334–344. 10.1101/gad.13.3.334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevillen P., Yang H., Cui X., Greeff C., Trick M., Qiu Q., et al. (2014). Epigenetic reprogramming that prevents transgenerational inheritance of the vernalized state. Nature 515, 587–590. 10.1038/nature13722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P., Ito T., Wellmer F., Vernoux T., Dedieu A., Traas J., et al. (2009). Floral stem cell termination involves the direct regulation of AGAMOUS by PERIANTHIA. Development 136, 1605–1611. 10.1242/dev.035436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum G., Medzihradszky A., Suzaki T., Lohmann J. U. (2014). A mechanistic framework for noncell autonomous stem cell induction in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 14619–14624. 10.1073/pnas.1406446111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Buzas D. M., Ying H., Robertson M., Taylor J., Peacock W. J., et al. (2013). Arabidopsis Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 binding sites contain putative GAGA factor binding motifs within coding regions of genes. BMC Genomics 14:593. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyhle F., Sarkar A. K., Tucker E. J., Laux T. (2007). WUSCHEL regulates cell differentiation during anther development. Dev. Biol. 302, 154–159. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley K. W., Poethig R. S. (2011). Binding of the cyclophilin 40 ortholog SQUINT to Hsp90 protein is required for SQUINT function in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38184–38189. 10.1074/jbc.M111.290130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhorn J., Moreau F., Fletcher J. C., Carles C. C. (2014). ULTRAPETALA1 and LEAFY pathways function independently in specifying identity and determinacy at the Arabidopsis floral meristem. Ann. Bot. 114, 1497–1505. 10.1093/aob/mcu185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J. C. (2001). The ULTRAPETALA gene controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Development 128, 1323–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J. C., Brand U., Running M. P., Simon R., Meyerowitz E. M. (1999). Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283, 1911–1914. 10.1126/science.283.5409.1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan E. S., Xu Y., Wong J. Y., Geraldine Goh J., Sun B., Wee W. Y., et al. (2014). Jumonji demethylases moderate precocious flowering at elevated temperature via regulation of FLC in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 5, 5098. 10.1038/ncomms6098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Hardt R., Lenhard M., Laux T. (2002). WUSCHEL signaling functions in interregional communication during Arabidopsis ovule development. Genes Dev. 16, 1129–1138. 10.1101/gad.225202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K., Ohta M., Matsui K., Ohme-Takagi M. (2002). The SUPERMAN protein is an active repressor whose carboxy-terminal repression domain is required for the development of normal flowers. FEBS Lett. 514, 351–354. 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02435-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L., Liu X., Yan J., Wang W., Yumul R. E., Kim Y. J., et al. (2011). ARGONAUTE10 and ARGONAUTE1 regulate the termination of floral stem cells through two microRNAs in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 7:e1001358. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek B. A., Fletcher J. C. (2005). Molecular mechanisms of flower development: an armchair guide. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 688–698. 10.1038/nrg1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C. S., Chen C., Wagner D. (2005). WUSCHEL is a primary target for transcriptional regulation by SPLAYED in dynamic control of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 19, 992–1003. 10.1101/gad.1276305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Baum S. F., Alvarez J., Patel A., Chitwood D. H., Bowman J. L. (2005). Activation of CRABS CLAW in the nectaries and carpels of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 25–36. 10.1105/tpc.104.026666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard M., Bohnert A., Jurgens G., Laux T. (2001). Termination of stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis floral meristems by interactions between WUSCHEL and AGAMOUS. Cell 105, 805–814. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00390-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Dinh T. T., Li D., Shi B., Li Y., Cao X., et al. (2014b). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 3 integrates the functions of AGAMOUS and APETALA2 in floral meristem determinacy. Plant J. 80, 629–641. 10.1111/tpj.12658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Gao L., Dinh T. T., Shi T., Li D., Wang R., et al. (2014a). DNA topoisomerase I affects polycomb group protein-mediated epigenetic regulation and plant development by altering nucleosome distribution in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2803–2817. 10.1105/tpc.114.124941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Kim Y. J., Muller R., Yumul R. E., Liu C., Pan Y., et al. (2011). AGAMOUS terminates floral stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis by directly repressing WUSCHEL through recruitment of Polycomb Group proteins. Plant Cell 23, 3654–3670. 10.1105/tpc.111.091538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann J. U., Hong R. L., Hobe M., Busch M. A., Parcy F., Simon R., et al. (2001). A molecular link between stem cell regulation and floral patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell 105, 793–803. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00384-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Cui X., Zhang S., Jenuwein T., Cao X. (2011). Arabidopsis REF6 is a histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase. Nat. Genet. 43, 715–719. 10.1038/ng.854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A. T., Stehling-Sun S., Wollmann H., Demar M., Hong R. L., Haubeiss S., et al. (2009). Dual roles of the bZIP transcription factor PERIANTHIA in the control of floral architecture and homeotic gene expression. Development 136, 1613–1620. 10.1242/dev.033647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel T., Moreau F., Kutsher Y., Fletcher J. C., Carles C. C., Eshed Williams L. (2014). The ERECTA receptor kinase regulates Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem size, phyllotaxy and floral meristem identity. Development 141, 830–841. 10.1242/dev.104687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K. F., Schoof H., Haecker A., Lenhard M., Jurgens G., Laux T. (1998). Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell 95, 805–815. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81703-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y., Ma H. (1997). Determination of Arabidopsis floral meristem identity by AGAMOUS. Plant Cell 9, 393–408. 10.1105/tpc.9.3.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J., Hart C. M., Francis N. J., Vargas M. L., Sengupta A., Wild B., et al. (2002). Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111, 197–208. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00976-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J., Kassis J. A. (2006). Polycomb response elements and targeting of Polycomb group proteins in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16, 476–484. 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne T., Johnson S. D., Koltunow A. M. (2004). KNUCKLES (KNU) encodes a C2H2 zinc-finger protein that regulates development of basal pattern elements of the Arabidopsis gynoecium. Development 131, 3737–3749. 10.1242/dev.01216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge M. J., Otsuga D., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., Drews G. N., Clark S. E. (2005). Class III homeodomain-leucine zipper gene family members have overlapping, antagonistic, and distinct roles in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 17, 61–76. 10.1105/tpc.104.026161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunet N., Morel P., Thierry A. M., Eshed Y., Bowman J. L., Negrutiu I., et al. (2008). REBELOTE, SQUINT, and ULTRAPETALA1 function redundantly in the temporal regulation of floral meristem termination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 20, 901–919. 10.1105/tpc.107.053306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G. V., Heisler M. G., Ehrhardt D. W., Meyerowitz E. M. (2004). Real-time lineage analysis reveals oriented cell divisions associated with morphogenesis at the shoot apex of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131, 4225–4237. 10.1242/dev.01261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Running M. P., Meyerowitz E. M. (1996). Mutations in the PERIANTHIA gene of Arabidopsis specifically alter floral organ number and initiation pattern. Development 122, 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Medrano L. J., Meyerowitz E. M. (1995). Role of SUPERMAN in maintaining Arabidopsis floral whorl boundaries. Nature 378, 199–203. 10.1038/378199a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoof H., Lenhard M., Haecker A., Mayer K. F., Jurgens G., Laux T. (2000). The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems in maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell 100, 635–644. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80700-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaczniak C., Immink R. G., Muino J. M., Blanvillain R., Busscher M., Busscher-Lange J., et al. (2012). Characterization of MADS-domain transcription factor complexes in Arabidopsis flower development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1560–1565. 10.1073/pnas.1112871109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. R., Willmann M. R., Wu G., Berardini T. Z., Moller B., Weijers D., et al. (2009). Cyclophilin 40 is required for microRNA activity in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5424–5429. 10.1073/pnas.0812729106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth D. R., Bowman J. L., Meyerowitz E. M. (1990). Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2, 755–767. 10.1105/tpc.2.8.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., Looi L. S., Guo S., He Z., Gan E. S., Huang J., et al. (2014). Timing mechanism dependent on cell division is invoked by Polycomb eviction in plant stem cells. Science 343, 1248559. 10.1126/science.1248559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., Xu Y., Ng K. H., Ito T. (2009). A timing mechanism for stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the Arabidopsis floral meristem. Genes Dev. 23, 1791–1804. 10.1101/gad.1800409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D., Meyerowitz E. M. (2002). SPLAYED, a novel SWI/SNF ATPase homolog, controls reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 12, 85–94. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00651-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L., Grigg S. P., Xie M., Christensen S., Fletcher J. C. (2005). Regulation of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem and lateral organ formation by microRNA miR166g and its AtHD-ZIP target genes. Development 132, 3657–3668. 10.1242/dev.01942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. F., Sang Y., Bezhani S., Yamaguchi N., Han S. K., Li Z., et al. (2012). SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeling ATPases overcome polycomb repression and control floral organ identity with the LEAFY and SEPALLATA3 transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 3576–3581. 10.1073/pnas.1113409109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn A. N., Seaman A. A., Jones A. L., Franks R. G. (2014). Novel functional roles for PERIANTHIA and SEUSS during floral organ identity specification, floral meristem termination, and gynoecial development. Front. Plant Sci. 5:130. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R. K., Perales M., Gruel J., Girke T., Jonsson H., Reddy G. V. (2011). WUSCHEL protein movement mediates stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Genes Dev. 25, 2025–2030. 10.1101/gad.17258511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. (2014). Plant science. Delayed gratification—waiting to terminate stem cell identity. Science 343, 498–499. 10.1126/science.1249343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Clarenz O., Cokus S., Bernatavichute Y. V., Pellegrini M., Goodrich J., et al. (2007). Whole-genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 5:e129. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Kim Y., Dinh T. T., Chen X. (2007). miR172 regulates stem cell fate and defines the inner boundary of APETALA3 and PISTILLATA expression domain in Arabidopsis floral meristems. Plant J. 51, 840–849. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03181.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga-Mayo V. M., Marsch-Martinez N., de Folter S. (2012). JAIBA, a class-II HD-ZIP transcription factor involved in the regulation of meristematic activity, and important for correct gynoecium and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 71, 314–326. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04990.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]