Abstract

After a dengue outbreak in Key West, Florida, during 2009–2010, authorities, considered conducting the first US release of male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes genetically modified to prevent reproduction. Despite outreach and media attention, only half of the community was aware of the proposal; half of those were supportive. Novel public health strategies require community engagement.

Keywords: dengue, Aedes aegypti, OX513A, mosquitoes, dengue, viruses, genetically modified, sterile, awareness, support, Key West, Florida

Two rapidly emerging viruses, chikungunya and dengue, are spread by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (1). Vector population control strategies have had variable success, and control by using genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes is under consideration (2). In trials, 1 GM variant, the OX513A Ae. aegypti, has survived under field conditions and reduced wild-type populations (3,4). However, there were concerns among public health officials, ecologists, and entomologists that the measures used to engage and inform local communities were too limited (5,6). Community support has been linked to the success (7) and failure (8) of vector and pest control campaigns.

The Study

During 2009–2010, an outbreak of dengue fever occurred in Key West, Florida (9). Shortly thereafter, the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District proposed the first release of a GM mosquito, OX513A Ae. aegypti, in the United States. The proposal was met with controversy.

On publication of this article, the release was undergoing inspection by the US Food and Drug Administration and had not occurred.

We conducted a survey in June 2012 to examine awareness and support of the release after 80 media and outreach activities had been conducted in Key West and Stock Island, Florida. We randomly selected 400 residences from the Monroe County Property Appraisers Office database and administered a cross-sectional knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey about mosquito control and dengue virus.

We collected information on demographics, perception of dengue risk, mosquito knowledge and prevention activities, and health care–seeking behavior, among other topics. Support was determined on a scale of 1 (strongly oppose) to 5 (strongly support). We requested reasons for participants’ level of support; themes raised by ≥9 respondents were coded into study categories by 2 investigators (K.C.E. and M.H.H.).

In this study, the use of GM male mosquitoes results in death of offspring in the larval or pupal stage of gestation; because of this outcome, outreach activities in the area preceding the survey referred to the mosquitoes as “sterile.” The survey we used included “sterile” because this term had been used in community awareness activities and should have been familiar to those who had heard of the proposed release, and we added “genetically modified” as a descriptor of the mosquitoes.

We divided participant groups into participants into those who had or had not heard of the release plans. We used logistic regression to assess associations between hearing of the release and possible explanatory factors. Missing values for household income were imputed. Distribution of levels of support of the release among those who had heard of the plan was stratified and tested for differences by demographic factors and participation in dengue and mosquito awareness and prevention activities. We used the Mantel-Haenszel test for trend for ordinal variables (e.g., education, income) and the χ2 test of heterogeneity for categorical variables. We used ANOVA, a nested analysis of variance approach, for continuous variables.

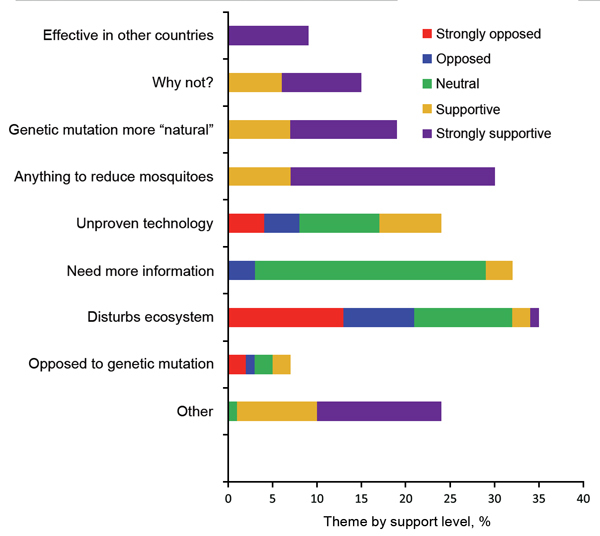

Of the 400 participants (Table 1), 75 (18.8%) were from the originally selected households. Of the 386 participants who responded to the question of whether they had heard of the proposed release before the survey, 195 (51.1%) answered “yes.” Prior awareness was more common in white non-Hispanics, residents with income levels >$50,000 per year, older adults, those who resided on Key West Island, and residents with knowledge of the local Action to Break the Cycle of Dengue public health campaign (Table 1). Among the 195 who were aware of the release, the distribution of support was: 9.7% strongly opposed, 8.2% opposed, 25.1% neutral, 22.1% supportive, and 34.9% strongly supportive. Men, less educated persons, and those willing to pay $100 or more for mosquito control were more likely to be strongly supportive (Table 2). The most common reasons for opposing the release were disturbance of nature and that it was an unproven technology. Most supporters of the release expressed a desire to do anything to get rid of mosquitoes or preferred the method to chemicals and spraying (Figure). On the basis of effectiveness, safety, and/or lack of unintended consequences, 22 of the 195 indicated that their support was conditional.

Table 1. Comparison of 400 surveyed local residents who had heard of release of genetically modified “sterile” male Aedes aegypti OX513A mosquitoes to those who had not, Key West, Florida, USA*.

| Response | Sample distribution, no. (%)† | Heard, %‡ | Not heard, % | Imputed unadjusted OR (95% CI), p value | Average adjusted OR (95% CI), multiply imputed data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||||

| 18–35 | 98 (25.1) | 19 | 81.1 | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| 36–50 | 77 (19.7) | 55.3 | 44.7 | 5.16 (2.61–10.2), <0.001 | 3.75 (1.75–8.03), <0.001 |

| 51–65 | 121 (31.0) | 71.8 | 28.2 | 10.5 (5.48–20.1), <0.001 | 8.17 (3.95–16.9), <0.001 |

| >66 |

94 (24.1) |

56.8 |

43.2 |

5.51 (2.84–10.7), <0.001 |

6.80 (3.14–14.7), <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| M | 214 (53.9) | 56 | 44 | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| F |

183 (46.1) |

45.3 |

54.8 |

0.65 (0.43–0.97), 0.03 |

0.58 (0.35–0.95), 0.03 |

| Region of Key West | |||||

| Old Town | 153 (38.4) | 51 | 49 | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Midtown | 61 (15.3) | 55.2 | 44.8 | 1.17 (0.64–2.16), 0.60 | 1.33 (0.62–2.85), 0.46 |

| New Town | 126 (31.6) | 57.4 | 42.6 | 1.29 (0.80–2.09), 0.29 | 1.53 (0.82–2.83), 0.18 |

| Stock Island |

59 (14.8) |

33.9 |

66.1 |

0.49 (0.26–0.93), 0.03 |

0.65 (0.29–1.44), 0.29 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White non-Hispanic | 247 (66.9) | 63 | 37 | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| White Hispanic | 46 (12.5) | 36.4 | 63.6 | 0.33 (0.17–0.64), 0.001 | 0.47 (0.21–1.04), 0.06 |

| Black | 38 (10.3) | 30.3 | 69.7 | 0.24 (0.11–0.53), <0.001 | 0.36 (0.15–0.90), 0.03 |

| Other |

38 (10.3) |

27 |

73 |

0.21 (0.10–0.42), <0.001 |

0.25 (0.11–0.56), <0.001 |

| Household income | |||||

| <$35,000 | 54 (13.5) | 44 | 46 | 0.29 (0.14–0.60), <0.001 | 0.75 (0.31–1.82), 0.53 |

| $35,000-$49,999 | 31 (7.8) | 41.9 | 48.1 | 0.37 (0.15–0.90), 0.03 | 0.83 (0.30–2.30), 0.72 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 52 (13.0) | 64.7 | 35.3 | 0.63 (0.30–1.32), 0.22 | 0.92 (0.41–2.08), 0.85 |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 37 (9.3) | 54.1 | 46 | 0.50 (0.22–1.15), 0.10 | 0.77 (0.31–1.92), 0.58 |

| >$100,000 |

72 (18.0) |

70.8 |

29.2 |

1 (Referent) |

1 (Referent) |

| Education level | |||||

| High school or lower | 123 (31.6) | 34.8 | 65.2 | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Some college | 77 (19.8) | 45.3 | 54.7 | 1.54 (0.85–2.79), 0.15 | 1.71 (0.83–3.54), 0.15 |

| Associate’s degree | 19 (4.9) | 68.4 | 31.6 | 3.83 (1.35–10.8), 0.01 | 5.73 (1.61–20.3), 0.007 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 107 (27.5) | 55.7 | 44.3 | 2.38 (1.38–4.08), 0.002 | 1.93 (0.97–3.81), 0.059 |

| Graduate or

professional degree |

63 (16.2) |

77.8 |

22.2 |

6.63 (3.27–13.4), <0.001 |

3.37 (1.42–8.02), 0.006 |

| Aware of ABCD§ | |||||

| No | 48 (19.0) | 59.6 | 40.4 | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Yes | 252 (81.0) | 79.2 | 20.8 | 2.56 (1.27– 5.14), 0.008 | 2.32 (1.04–5.17), 0.04 |

*All variables listed are included in the adjusted model. †Demographic totals may not add up to 400 because some participants refused to report demographic information. ‡Percentages reflect within category percentages. §ABCD, Florida Keys-based Action to Break the Cycle of Dengue public health campaign.

Table 2. Percentage of responses to demographic, dengue and mosquito-related factors according to level of support for a release of genetically modified “sterile” mosquitoes in Key West, Florida, USA, among the 195 participants who had heard of the release*.

| Response | Strongly opposed | Somewhat opposed | Neutral | Somewhat supportive | Strongly supportive | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall level of support, no. (%) | 19 (9.7) | 16 (8.2) | 49 (25.1) | 43 (22.1) | 68 (34.9) | NA |

| Mosquitoes noticed outside (%, many or very many) | 26.3 | 12.5 | 14.6 | 11.9 | 22.1 | 0.87† |

| How many days did you spend outside last week, % >3 d | 79.0 | 68.8 | 83.7 | 79.1 | 75.0 | 0.75† |

| Limit outdoor activity because of mosquitoes, % often or always | 10.5 | 6.3 | 10.2 | 4.7 | 8.8 | 0.80† |

| Able to report dengue as a mosquito-carried disease, % yes | 84.2 | 87.5 | 75.5 | 79.1 | 80.9 | 0.78† |

| How serious is dengue in Key West, % very or extremely serious | 31.6 | 43.8 | 38.6 | 40.0 | 31.3 | 0.63† |

| How likely is it that you or a family member will get dengue in Key West, % somewhat or very likely | 10.5 | 18.8 | 10.6 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 0.78† |

| Aware of ABCD, % yes | 15.8 | 18.8 | 26.1 | 29.0 | 14.3 | 0.68† |

| Willing to pay $100 or more for effective mosquito control, %, yes | 28.6 | 50.0 | 58.7 | 73.5 | 73.3 | <0.001† |

| Current mosquito control is very or extremely effective, % yes |

66.7 |

75.0 |

75.5 |

69.8 |

72.1 |

0.97† |

| Mean age, y |

57.8 |

52.6 |

54.7 |

56.2 |

57.7 |

0.67‡ |

| Distribution of support by category | ||||||

| Sex | <0.001§ | |||||

| M | 10.5 | 6.1 | 18.4 | 17.5 | 47.4 | ND |

| F | 8.6 | 11.1 | 34.6 | 28.4 | 17.3 | ND |

| Key West region | 0.29§ | |||||

| Old Town | 13.3 | 8.0 | 25.3 | 20.0 | 33.3 | ND |

| Midtown | 3.1 | 9.4 | 34.4 | 25.0 | 28.1 | ND |

| New Town | 7.3 | 7.3 | 26.1 | 17.4 | 42.0 | ND |

| Stock Island | 15.8 | 10.5 | 5.3 | 42.1 | 26.3 | ND |

| Race | 0.21§ | |||||

| White non-Hispanic | 9.2 | 8.5 | 24.2 | 20.9 | 37.3 | ND |

| White Hispanic | 6.3 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 37.5 | 37.5 | ND |

| Black | 0.0 | 10.0 | 50.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | ND |

| Other race | 30.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | ND |

| Household income | 0.16† | |||||

| <$35,000 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 18.2 | 27.3 | 27.3 | ND |

| $35,000-$49,999 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 7.7 | 46.2 | 23.1 | ND |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 12.5 | 3.1 | 21.9 | 18.8 | 43.8 | ND |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | ND |

| >$100,000 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 27.5 | 13.7 | 47.1 | ND |

| Highest level of education | 0.09† | |||||

| Lower than high school | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | ND |

| High school graduate | 0.0 | 5.6 | 19.4 | 25.0 | 50.0 | ND |

| Some college | 15.6 | 12.5 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 21.9 | ND |

| Associate degree | 7.7 | 0.0 | 30.8 | 23.1 | 38.5 | ND |

| Bachelor’s degree | 11.9 | 10.2 | 28.8 | 18.6 | 30.5 | ND |

| Graduate or professional degree | 12.2 | 6.1 | 24.5 | 20.4 | 36.7 | ND |

*NA, not applicable; ND, calculation not done; ABCD, Florida Keys-based Action to Break the Cycle of Dengue public health campaign. †p value for trend calculated by using Mantel-Haenszel test. ‡p value calculated by using nested analysis of variance. §p value calculated by using χ2 test for heterogeneity.

Figure.

Proportion of respondents reporting different themes for their level of support of plans to release genetically modified, referred to as “sterile,” male mosquitoes on Key West, Florida, USA.

Conclusions

For community acceptance of the release of GM mosquitoes, several issues must be addressed. Release of GM mosquitoes into the community should be transparent; therefore, the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District has begun to disseminate information through public events, articles, and presentations. Identification of solutions to reduce risk for vector-borne disease should involve stakeholders from the public, and community leaders in public health, vector control, and municipal administrators. Open communication with community members and stakeholders through a health advisory board was instrumental in quelling a 1989 invasion of Mediterranean fruit flies in California that had become a crisis event (10). In Key West and Stock Island, public awareness and communication campaigns had limited success. Awareness of the release varied across sections of the city and by demographic group. At the time of the survey, the release was planned for Key West; in Stock Island, awareness was much lower. Adjacent areas should be included in communications because residents and Ae. aegypti are mobile. (11). Knowledge of current events has been associated with gender, education level, race and ethnicity, and age (12). Outreach should target groups with a tendency towards lower awareness of public health measures.

Support was more commonly reported than opposition among those aware of the release; a large portion was neutral. Most neutral respondents reported they did not know enough to make a decision, and many supporters wanted more information or had concerns. To progress from awareness to knowledge, to understanding, and then to decision-making would require considerable effort and improvement in overall scientific literacy (13). The scientific community is divided about the amount of information that should be provided to community members on highly technical vector control strategies such as the release of the OX513A mosquito (14). Benchmarks for acceptable engagement and support should be set by public health organizations before GM vector releases are planned, which will require input from scientists, stakeholders, and the community.

Strongly opposed participants most commonly reported unintended consequences or disturbing natural ecosystems as their reason for opposition. Conversely, some supporters considered the mosquito release a more natural way of controlling mosquito populations than insecticides. This was substantiated in a follow-up study (15).

This study has several limitations. Participants may not have fully represented the community because of seasonal housing closures and inaccessibility of some gated communities. A systematic replacement strategy was used to minimize bias. To obtain information on support, we provided a short statement about the release, modeled after earlier community outreach efforts and that used the term “sterile mosquito” instead of “genetically modified mosquito.” We excluded responses of participants without prior awareness from our analysis because our informational statement was cursory. Follow-up studies in Key West that provided more extensive information yielded the same 9% strong opposition rate (15).

Introduction of GM mosquitoes has the potential to reduce mosquito-borne disease; however, little data exist on the type and extent of outreach required or community support needed to reduce opposition. As of December 2014, a short-term release of Oxitec OX513A mosquitoes is proposed on Key Haven, a peninsula adjacent to Key West. This is part of an application by Oxitec: Regulatory Clearance for Investigational Use of a New Animal Drug. This release is proposed before broader implementation in Key West or elsewhere in the Florida Keys (M.S. Doyle, unpub. data). If approved, this release could serve as a model of best practices for establishing community relations and engagement before implementing vector control strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jaclyn Pierson, Adam Resnick, Syed Ali Raza, Linsay Edinger, Mindy Butterworth, Melissa Roberts, and Kevin Hayden for collecting data; and Emily Zielinski-Gutierrez, Christopher Tittel, Robert Eadie, Carina Blackmore, Danielle Stanek, and Lisa Conti for protocol and survey development and community engagement.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R56AI091843 and R01AI091843. The National Center for Atmospheric Research is supported in part by the National Science Foundation.

A disclosure statement was read to each participant. The protocol was approved by the University of Arizona Human Subjects Research Committee and deemed exempt.

Biography

Dr. Ernst is an assistant professor in the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Division of the University of Arizona College of Public Health. Her research interests focus on understanding the environmental and social factors that influence transmission of vector-borne disease, primarily malaria and dengue, and identifying community-based strategies to control them.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ernst KC, Haenchen S, Dickinson K, Doyle MS, Walker K, Monaghan AJ, Hayden MH. Awareness and support of release of genetically modified “sterile” mosquitoes, Key West, Florida, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Feb [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2102.141035

References

- 1.Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:328–45 . 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser MJ Jr. Insect transgenesis: current applications and future prospects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2012;57:267–89. 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris AF, McKemey AR, Nimmo D, Curtis Z, Black I, Morgan SA, et al. Successful suppression of a field mosquito population by sustained release of engineered male mosquitoes. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:828–30. 10.1038/nbt.2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacroix R, McKemey AR, Raduan N, Kwee Wee L, Hong Ming W, Guat Ney T, et al. Open field release of genetically engineered sterile male Aedes aegypti in Malaysia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42771 . 10.1371/journal.pone.0042771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subbaraman N. Science snipes at Oxitec transgenic-mosquito trial. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramaniam TS, Lee HL, Ahmad NW, Murad S. Genetically modified mosquito: the Malaysian public engagement experience. Biotechnol J. 2012;7:1323–7. 10.1002/biot.201200282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumhover AH. A personal account of developing the sterile insect technique to eradicate the screwworm from Curacao, Florida and the southeastern United States. Fla Entomol. 2002;85:666–73. 10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085[0666:APAODT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reuben R, Rahman S, Panicker K, Das P, Brooks G. The development of a strategy for large-scale releases of sterile males of Aedes aegypti (L.). J Commun Dis. 1975;7:313–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locally acquired dengue–Key West, Florida, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:577–81 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5919a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn E, Jackson RJ, Lyman DO, Stratton JW. A crisis of community anxiety and mistrust: the medfly eradication project in Santa Clara County, California, 1981–82. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1301–4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1404895/. 10.2105/AJPH.80.11.1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guagliardo SA, Barboza JL, Morrison AC, Astete H, Vazquez-Prokopec G, Kitron U. Patterns of geographic expansion of Aedes aegypti in the Peruvian Amazon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3033 http://dx.doi.org10.1371/journal.pntd.0003033. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Public knowledge of current affairs little changed by news and information revolutions. [cited 12/Dec/2014]. Washington, DC: The Center; 2007;1–33 http://www.people-press.org/2007/04/15/public-knowledge-of-current-affairs-little-changed-by-news-and-information-revolutions/

- 13.Culliton BJ. The dismal state of scientific literacy: studies find only 6% of Americans and 7% of British meet standard for science literacy. Science. 1989;243:600. 10.1126/science.243.4891.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boete C. Scientists and public involvement: a consultation on the relation between malaria, vector control and transgenic mosquitoes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:704–10. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobb MD. Public perceptions of GE mosquito control efforts in Key West: an in-person survey of 205 K.W. residents, January 1–5, 2013: North Carolina State University; 2013 [cited 15 Dec 2014]. http://keysmosquito.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Key-West-Survey-Results-2013.pdf