To the Editor: Meningococcal disease in US military personnel is controlled by vaccines, the first of which was developed by the US Army (1–5). In 1985, the quadrivalent polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV-4) was implemented as the military standard. It was replaced during 2006–2008 by the quadrivalent conjugate vaccine (MCV-4). Every person entering US military service is required to receive this vaccine.

Meningococcal disease incidence in active-duty US military personnel, historically far above that in the general population (6), has decreased >90% since the early 1970s, when the first vaccine was introduced (7). Over the last 5 years, incidences in the military and US general populations have become equivalent (8). Here we update previously published data (8) from the Naval Health Research Center’s Laboratory-based Meningococcal Disease Surveillance Program of US military personnel. Data-gathering methods and laboratory analyses of samples from personnel suspected of having meningococcal disease have been previously described (8). Incidences were compared by using the New York State Department of Public Health Assessment Indicator based on the methods of Breslow and Day (9).

During 2006–2013 in US military personnel, only 1 of the 28 meningococcal disease cases for which serogroup data are available was not serogroups C or B (8 cases each) or Y (11 cases). During that period, incidence in US military personnel of 0.271 cases per 100,000 person-years did not differ significantly (p>0.05) from that of 0.238 in the 2006–2012 age-matched US general population (persons 17–64 years of age) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], unpub. data). During 2010–2013, meningococcal disease incidence in military personnel was 0.174 cases per 100,000 person-years, compared with 0.194 in the age-matched 2010–2012 US population. Among military personnel, only 1 case each occurred in 2011 (serogroup Y) and 2012 (serogroup B), and 3 occurred in 2013 (1 each of serogroups B, C, and Y).

To measure the relative success of the 2 vaccines, we compared incidence among military personnel who had received MPSV-4 with that of personnel who had received MCV-4. In 2006, MCV-4 was introduced to new recruits. The proportion of military personnel who had received MCV-4, rather than MPSV-4, increased from 6% of the military population (63,000 persons) in 2006 to 64% (930,000) in 2013. By 2013, a total of 99% of new vaccinations were of MCV-4. Overall incidence in personnel receiving MCV-4 was 0.298 cases per 100,000 person-years during 2006–2013, which was lower, although not significantly lower (p>0.05), than 0.410 cases per 100,000 person-years in MPSV-4 recipients during 2000–2013.

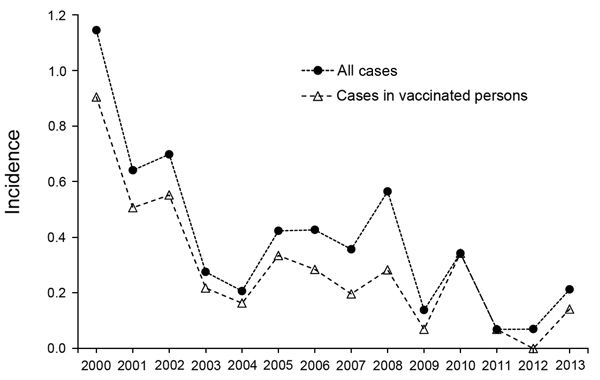

However, because neither vaccine covers serogroup B, excluding serogroup B cases in the vaccine-related incidence calculations might be more appropriate. Incidence in MCV-4–vaccinated personnel during 2006–2013, excluding serogroup B cases, was 0.183. Specific serogroup data are not available for 2000–2005, so to calculate non–serogroup B incidence during this period, we estimated the proportion of serogroup B cases by examining a range of estimates of serogroup B proportions derived from the true proportions in all 6-year periods during 1995–2012 in the US general population (range 21%–35%; 35% during 2000–2005) (CDC, unpub. data) and during 2006–2013 in US military personnel (range 22%–28%). Adopting (from our estimated range of serogroup B proportions) 21% as the percentage that would have made the MPSV-4–related incidence the highest, MPSV-4–related incidence (i.e., excluding serogroup B cases) during 2000–2013 would have been 0.307, which did not differ significantly from incidence of MCV-4 non-serogroup B cases (p>0.05). (Using higher percentages would have pushed the MPSV-4 estimate even closer to the MCV-4 incidence.) The Figure shows pooled incidence for 2000–2013.

Figure.

Meningococcal disease incidence per 100,000 person-years in US military personnel, 2000–2013. Incidence in vaccinated personnel shown assumes that 21% of cases during 2000–2005 were caused by Neisseria meningitis sergroup B.

Results of these comparisons are subject to several limitations. First, because the relative proportions of the 2 vaccines changed, a differential effect of herd immunity caused by one or the other could have differentially suppressed rates. Second, along with the decrease in the MPSV-4 population, the average time from vaccination increased relative to the period in which MPSV-4 was given, concomitant with decreasing immunogenicity. Any elevated incidence in the MPSV-4–vaccinated population since 2006 could be associated with time since vaccination. Third, the same factors involved in the decline in incidence in the US general population that began in ≈2001 might be at play in the military, confounding the vaccine effects. Fourth, as the rate of vaccine coverage in the US population increased, a higher proportion of recruits might have entered the military already vaccinated; thus, their military vaccination was essentially a booster.

Meningococcal disease incidence decreased during 2000–2013. Our data suggest that cases in MCV-4–vaccinated personnel are similar to those in MPSV-4–vaccinated personnel, regardless of whether the incidence calculation includes cases caused by serogroup B (non–vaccine covered). More extensive study is needed to confirm the relative effects of the vaccines (10). Serogroup B accounted for 5 of the 8 cases during 2012–September 2014), and prevention of disease caused by this serotype remains a challenge.

Acknowledgment

We thank CDC’s Meningitis and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Branch for providing the US disease data.

The Naval Health Research Center Meningococcal Disease Surveillance is supported by the Global Emerging Infections System division of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center.

The meningococcal disease surveillance in the US military produces a quarterly report, which is available online: http://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nhrc/geis/Documents/MGCreport.pdf

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Broderick MP, Phillips C, Faix D. Meningococcal disease in US military before and after adoption of conjugate vaccine [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Feb [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2102.141037

References

- 1.Goldschneider I. Vaccination against meningococcal meningitis. Conn Med. 1970;34:335–9 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldschneider I, Gotschlich EC, Artenstein MS. Human immunity to the meningococcus. II. Development of natural immunity. J Exp Med. 1969;129:1327–48. 10.1084/jem.129.6.1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldschneider I, Lepow ML, Gotschlich EC. Immunogenicity of the group A and group C meningococcal polysaccharides in children. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:509–19. 10.1093/infdis/125.5.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotschlich EC, Goldschneider I, Artenstein MS. Human immunity to the meningococcus. V. The effect of immunization with meningococcal group C polysaccharide on the carrier state. J Exp Med. 1969;129:1385–95. 10.1084/jem.129.6.1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotschlich EC, Goldschneider I, Artenstein MS. Human immunity to the meningococcus. IV. Immunogenicity of group A and group C meningococcal polysaccharides in human volunteers. J Exp Med. 1969;129:1367–84. 10.1084/jem.129.6.1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brundage JF, Zollinger WD. Evolution of meningococcal disease epidemiology in the US Army. In: Vedros NA, editor. Evolution of meningococcal disease, Vol. I. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press: 1987. p. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brundage JF, Ryan MA, Feighner BH, Erdtmann FJ. Meningococcal disease among United States military service members in relation to routine uses of vaccines with different serogroup-specific components, 1964–1998. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1376–81. 10.1086/344273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broderick MP, Faix DJ, Hansen CJ, Blair PJ. Trends in meningococcal disease in the United States military, 1971–2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1430–7. 10.3201/eid1809.120257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslow N, Day NE. The design and analysis of cohort studies. In: Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol. II. Oxford (UK): IARC Scientific Publications; 1988. p. 445–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel M, Romero-Steiner S, Broderick MP, Thomas CG, Plikaytis BD, Schmidt DS, et al. Persistence of serogroup C antibody responses following quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccination in United States military personnel. Vaccine. 2014;32:3805–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]