Significance

We report a remarkable reversible change in structure of vanadium dioxide films when gated with an ionic liquid. We show that the film expands by more than 3% in the out-of-plane direction when gated to the metallic state. This giant structural change is not only more than 10 times larger than the one at the thermally controlled insulator-to-metal transition measured in the same films, but is in the opposite direction—an expansion rather than a contraction. These results are very important to the field of ionic liquid gating, which has largely ignored the possibility that the high electric fields created on gating at the liquid–oxide interface can result in significant structural changes rather than a purely electrostatic phenomenon.

Keywords: electrolyte gating, correlated oxides, EXAFS, metal–insulator transition, vanadium dioxide

Abstract

The use of electric fields to alter the conductivity of correlated electron oxides is a powerful tool to probe their fundamental nature as well as for the possibility of developing novel electronic devices. Vanadium dioxide (VO2) is an archetypical correlated electron system that displays a temperature-controlled insulating to metal phase transition near room temperature. Recently, ionic liquid gating, which allows for very high electric fields, has been shown to induce a metallic state to low temperatures in the insulating phase of epitaxially grown thin films of VO2. Surprisingly, the entire film becomes electrically conducting. Here, we show, from in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction and absorption experiments, that the whole film undergoes giant, structural changes on gating in which the lattice expands by up to ∼3% near room temperature, in contrast to the 10 times smaller (∼0.3%) contraction when the system is thermally metallized. Remarkably, these structural changes are fully reversible on reverse gating. Moreover, we find these structural changes and the concomitant metallization are highly dependent on the VO2 crystal facet, which we relate to the ease of electric-field–induced motion of oxygen ions along chains of edge-sharing VO6 octahedra that exist along the (rutile) c axis.

The use of electric fields to influence the transport properties of various materials by electrostatic injection of charge at an interface is the foundation of much of modern day electronics (1). Using a three-terminal field-effect transistor geometry, the magnitude of the electric fields provided by conventional gate dielectrics is limited by their dielectric properties. Much higher electric fields are possible by replacing the conventional gate material with an ionic liquid. Consequently, much higher electrostatically induced charge densities are possible, leading to the control or creation of novel metallic (2–3) and superconducting phases (4–7). Materials that are insulating by virtue of strong electron–electron correlations, namely Mott–Hubbard and charge-transfer insulators (8), are anticipated to be particularly sensitive to the injection of small numbers of carriers that could result in their metallization (9–11). Often these materials exhibit a thermally driven insulator to metal transition: one of these, VO2, exhibits such a transition near room temperature (12, 13) and, for this reason, has been extensively studied (14–16). In VO2 the metal to insulator transition (MIT) is accompanied by a structural phase transition (SPT) in which the monoclinic insulating phase transforms to a rutile metallic phase (17). Recently, both Nakano et al. (18) and Jeong et al. (19) showed that ionic liquid (IL) gating of thin films of VO2 results in the suppression of the MIT to temperatures below ∼10 K and, moreover, that the entire film becomes metallic even though gating takes place at the top surface of the film in contact with the IL. However, whereas Nakano et al. (18) claimed the metallization phenomenon was a direct result of electrostatic carrier injection, Jeong et al. (19) presented clear evidence that the metallic state was rather induced by the electric-field–induced migration of oxygen from the film into the IL. An important question is whether the IL gating results in a structural phase transition, as supposed by Nakano et al. (18), or whether the initially insulating film remains in the monoclinic phase and the metallization results rather from the formation of oxygen vacancies (19). Here, we show, using in situ X-ray diffraction and absorption, that IL gating induces massive, reversible structural changes in which the VO2 (001) film expands and contracts along its thickness by up to 3%, but that the film remains in the monoclinic phase. Furthermore, we identify a remarkable dependence of the IL gating phenomenon on the crystal facet of the VO2 films. Whereas the (001) and (101) facets exhibit similar IL gate-induced metallization, almost no effect is observed for films grown with (100) and (110) facets. Because there are open channels in the VO2 crystal structure along the rutile c axis, we associate the IL gating phenomenon with the ease of migration of oxygen along these channels under the influence of electric field. Previously, clear evidence for the formation and refilling of oxygen vacancies under ionic liquid gating of VO2 (001) has been reported (19).

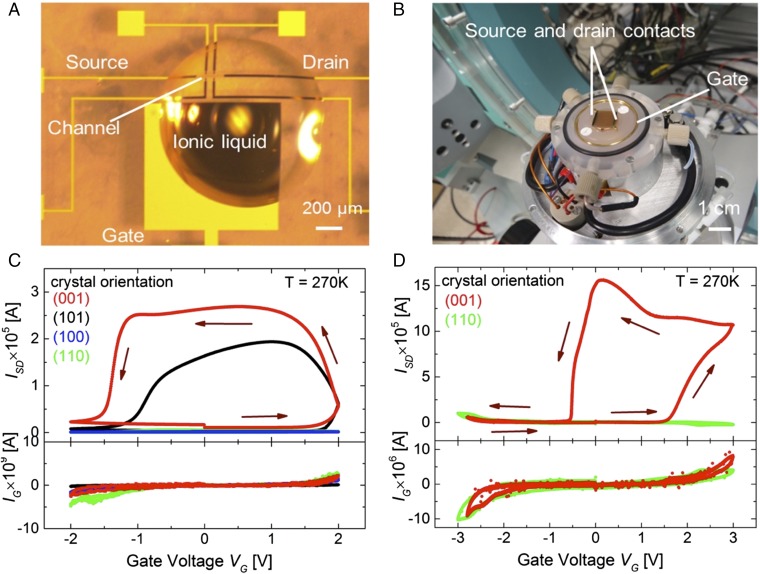

The facet-dependent IL-induced metallization and associated structural changes of VO2 were studied using two types of devices shown in Fig. 1 A and B, respectively. We label these devices as type T and X, respectively. In Fig. 1A a typical device type T with a channel area of 200 × 20 µm2 defined by optical lithography is shown (see Methods for details). The channel conductance is measured using the source (S) and drain (D) contacts that are shown in the figure. A drop of the IL (∼100 nl) fully covers the channel and a significant part of the lateral gate electrode (19). Such devices T are suitable for detailed transport studies as a function of temperature and environment. Fig. 1B shows a cell (20) that was specially designed for in situ synchrotron-based X-ray measurements. Device X, used in this cell, is much larger than that of Fig. 1A and indeed is almost as large as the substrate itself (1 × 1 cm2) with S and D gold contacts, defined by shadow masks, along opposite edges of the substrate. The device and the gate electrode, which is formed from a coiled Au wire that surrounds the device, are immersed in ∼2 mL of IL which is introduced through Teflon tubes and which is contained by a 7.5-µm-thick Kapton sheet, sealed with Viton O-rings, that allows for transmission of the incident and diffracted X-ray beams and fluorescent X-rays. The cell is attached to a four-circle X-ray goniometer for the X-ray diffraction studies. Incorporated within the cell is a heater and a Peltier cooler that allows for operation at temperatures ranging from ∼250 K to ∼400 K. Pulsed laser deposition was used to deposit 10-nm-thick VO2 films with four different crystal facets, (001), (101), (100), and (110) on single-crystalline substrates of TiO2 with the same respective crystal orientations, and 20-nm-thick VO2 (001) films on Al2O3(see Methods for details).

Fig. 1.

Two different types of ionic liquid devices and facet dependence of gating effect. (A) Optical image of a device with a droplet of HMIM-TFSI with channel size of 200 × 20 µm2. (B) Optical image of an ionic liquid device for in situ X-ray measurement. The entire film surface (10 × 10-mm2 area) is covered with ionic liquid surrounded by a Au wire used as a gate electrode. Source–drain (Top) and gate (Bottom) current versus VG for small size device (C) and large size device (D) fabricated from VO2 films grown on TiO2 substrates of different orientations. Gate voltages were swept at a rate of 3 mV/s (0.3 mV/s for D) and source–drain voltage (VSD) of 100 mV (300 mV for D) is applied.

Fig. 1 C and D compares the gate voltage (VG) dependence of the source–drain current ISD and the gate current IG at 270 K for devices X and T. Initially the devices are in the insulating phase but above a certain threshold gate voltage ISD increases substantially. When VG is decreased to zero the devices remain conducting and revert back to their original state only when reverse gated by applying a negative voltage. IG remains below 5 nA for all VG for device T. For device X, IG is much larger but only because of the much larger gated area: the leakage current per unit area of the gated VO2 is similar for both devices (see SI Appendix for a detailed comparison). In the fully gated state, device T is metallic to low temperatures as shown earlier (19) but device X was only measured to 250 K, due to limitations of the X-ray cell, where it remained metallic. An important result is the dramatic dependence of the IL gating on the VO2 crystal facet, as is clearly shown in Fig. 1 C and D.

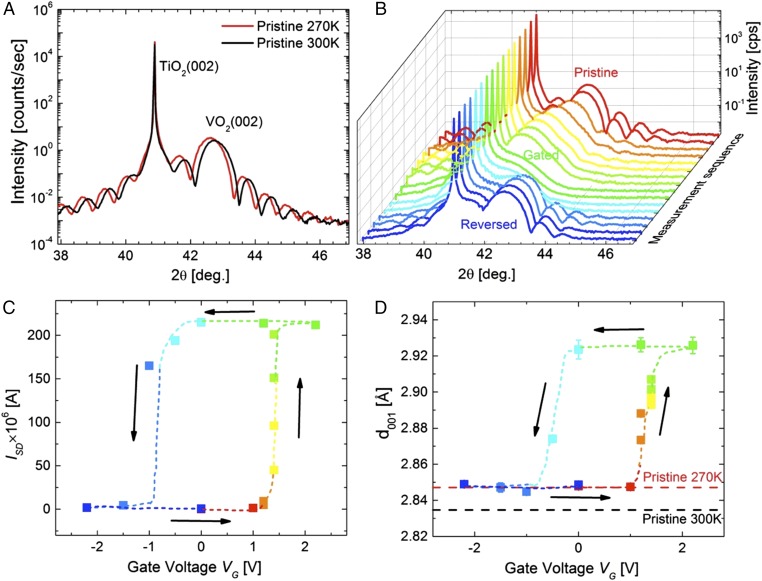

X-ray diffraction θ–2θ curves from a VO2 (001) device X in the insulating phase and the thermally induced metallic phase are shown in Fig. 2A. The unit cell (all peaks are indexed throughout the paper with respect to the rutile unit cell, for simplicity) contracts along the c axis as evidenced by the shift of the VO2 (002) peak to higher 2θ as VO2 transforms from the monoclinic to a rutile phase. Fig. 2B shows a sequence of X-ray θ–2θ curves for the device in different gated states as VG was systematically ramped in steps from 0 to +2.2 V to −2.2 V and back to zero. The X-ray data were collected after VG was fixed at each step for 30 min. Fig. 2C shows the corresponding values of ISD for these data. The gate voltage-induced increase in ISD is ∼3 orders of magnitude. The X-ray data show very large shifts in the VO2 (002) peak position which, however, are opposite to that seen for the temperature-driven MIT shown in Fig. 2A. The VO2 (002) peak rather shifts to smaller 2θ values. This corresponds, as shown in Fig. 2D, to an expansion of the c-axis parameter in the fully gated metallic state by a factor which is 10 times larger than the contraction in the c-lattice parameter that is observed for the temperature-driven SPT. We note that the threshold voltages at which the lattice changes are observed appear to be smaller than that at which ISD changes. We find that no structural changes are observed when the same experiment is carried out on a 10-nm-thick VO2 film grown with a (110) facet on TiO2(110). X-ray diffraction θ–2θ curves taken during gating at gate voltages of up to 2.8 V show no shift in the VO2 (220) peak position nor any other changes in the X-ray diffraction curves. As shown in Fig. 1D there are similarly no changes in ISD during gating up to VG = 3 V.

Fig. 2.

Structural changes of VO2/TiO2(001) by electrolyte gating as a function of gate voltages. (A) XRD patterns of insulating (red) phase at 270 K and metallic phase (black) at 300 K for 10-nm VO2/TiO2(001) with 12-keV photon energy. (B) XRD pattern for in situ X-ray measurements and (C) source–drain current (ISD) versus gate voltage (VG). Both XRD and ISD were measured ∼30 min after VG was applied. (D) c-axis lattice parameter extracted from B versus gate voltage. The error bars are from the nonlinear least-squares fitting algorithm and in many cases are smaller than the symbols.

The structural changes that we find on gating VO2 (001) are similar to those found by growing VO2 (001) films of comparable thickness at lower oxygen pressures during pulsed laser deposition. Fig. 3A shows X-ray diffraction θ–2θ curves for a series of five samples, each ∼10 nm thick, prepared at oxygen pressures of 9, 7, 5, 3, and 1 mTorr. As the oxygen pressure is reduced the c-lattice parameter systematically increases, as shown in Fig. 3B. The MIT transition is systematically broadened and suppressed to low temperatures as the oxygen pressure is reduced (19). The c-lattice parameter expansion caused by the introduction of oxygen vacancies by modifying the film growth conditions are similar to those that IL gating induces, and the resulting metallization of the VO2 films is comparable. We presume that the thickness oscillations in the θ–2θ curves from VO2/TiO2(001) in Fig. 2B that disappear on gating result from the loss of coherence in the film structure due to gating and the subsequent formation of oxygen vacancies.

Fig. 3.

Crystal structure of oxygen-deficient and gated VO2/TiO2(001). Dependence of (A) XRD θ–2θ curves, and (B) c-lattice parameter and TMIT on oxygen pressure during growth. (C) Reciprocal space maps of VO2(202) peak versus oxygen pressure during film growth and comparison with those for the pristine and gated states of a device formed from a film grown at 9 mtorr. (D) Structure of the monoclinic phase of VO2 looking along the <001> and <110> axes.

The crystal facet of the VO2 film is determined by epitaxial growth onto the respective facet of the TiO2 substrate. This also results in clamping of the 10-nm-thick VO2 films to the corresponding TiO2 lattices by coherent strain such that their in-plane unit cell parameters are very similar. This is illustrated in Fig. 3C, which shows reciprocal lattice maps centered near TiO2 (202) in the k = 0 plane for the five films prepared in different oxygen ambients in Fig. 3A. The maps show along the [20l] direction a very sharp, intense TiO2 (202) peak together with a weaker and broader VO2 (202) peak and associated Kiessig fringes (21). The VO2 (202) peak systematically shifts to lower l as the oxygen pressure is reduced. Along the [h02] direction, by contrast, the VO2 and TiO2 peaks have similar narrow widths that indicate in-plane clamping of the VO2 lattice to that of the TiO2 substrate. Thus, during IL gating it is anticipated that only the out-of-plane VO2 lattice parameter can be significantly changed. This is confirmed in the reciprocal space map for a sample that was gated at VG = 3 V for 10 h and the IL removed before the measurement using a laboratory X-ray source.

The clamping of the VO2 lattice to that of the TiO2 lattice could offer an explanation for the lack of any significant IL gating response for facets of VO2 for which the c axis lies in plane. It could be that to remove significant amounts of oxygen the lattice needs to expand along the c direction. It is along the rutile c direction that the structure comprises one-dimensional chains of edge-sharing VO6 octahedra that allow for the expansion and contraction of the VO2 lattice during IL gating (Fig. 3D).

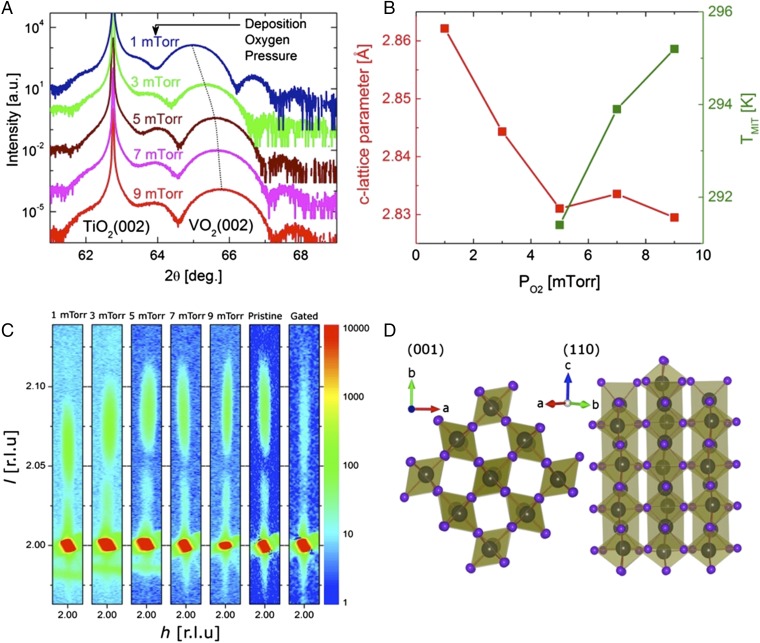

To inspect the local environment of V we performed in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) at the V K edge using VO2 (001) films grown on Al2O3rather than TiO2 to avoid the otherwise significant fluorescence from Ti in the substrate. The sample was gated and the XAS data were measured at ambient temperature well below the MIT of the pristine film. The X-ray absorption near-edge spectra (XANES) are shown in Fig. 4A for a pristine sample and the same sample after gating (VG = 3 V, 1 h) to a conducting state. The XANES data remain largely unchanged with two exceptions. Firstly, there is a small shift in the position of the inflection point of the V 1s→3d preedge transition and a small decrease in the intensity of the preedge peak that suggest a reduction in the valence state of the V ions [by ∼0.2 electrons per V (22)]. The decrease in the intensity of this preedge feature is also consistent with a decrease in the degree of distortion of the VO6 octahedra (22). Secondly, there is a small shift to lower photon energies in the position of the main V K edge and the white line (V1s → V4p transition) at this edge which is also consistent with a reduced V valence on gating (22). A change in V valence was previously observed in X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy measurements performed on electrolyte-gated VO2 that suggested the formation of oxygen vacancies on gating (19).

Fig. 4.

XAS of VO2/Al2O3. (A) Vanadium K-edge XANES for a pristine and gated device X. (B and C) χ(R) curves for the data and corresponding fits. The individual contributions to these fits from respective V–O and V–V shells are shown (inverted) in the bottom halves of B and C. The experimental data for the pristine and gated states are shown in blue and red, respectively; the fits to these data are shown in green; the differences between the experimental data and fits are shown in magenta; the contributions from V–O shells are shown in purple; the contributions from V–V shells along the dimer axis are brown and perpendicular to the dimer axis are dark yellow. The brown horizontal lines in B and C are aids to the eye, showing the degree of dimerization, namely, the difference between the intra- and inter-V–V dimer distances. The solid and dashed curves are the moduli and real parts of the Fourier transform of the EXAFS data and the fits, respectively. (D) Table of fitted V–O and V–V bond distances.

Much larger changes are observed in the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) (23), χ(k), that is most readily seen in its Fourier transform (FT), namely, χ(R) = FT(k3 χ(k)) (23), that is presented in Fig. 4 B and C. Detailed information on the types of locally ordered neighbor shells and their metrical parameters was obtained by nonlinear least-squares curve fits using calculated amplitudes and phases (24). The k3-weighted data were fit for k varying from 2.6 to 10.3 Å–1 so that shells are distinguishable only if separated by more than ∼0.15 Å. The spectra were well fit (Fig. 4 B and C) with a limited number of shells relative to the crystal structure (SI Appendix). The distances found for the pristine samples are consistent with the monoclinic phase of VO2 below its MIT in which the shorter V–V distances that correspond to those in the (rutile) c direction that is normal to the film plane are split because of the dimerization of the V–V atoms along this direction. In the pristine sample these V–V distances of 2.61 and 3.03 Å differ by 0.42 Å, whereas in the gated sample these distances become 2.94 and 3.16 Å and differ by only 0.22 Å. Note that the almost complete loss of the peak in the χ(R) spectra near R−ϕ = 2.0 Å on gating is not because of a radical change in the V–V chain ordering and departure from the V–V dimerized monoclinic structure, but is because the decreased separation between the short and long dimer V–V pairs causes their individual EXAFS waves to destructively interfere, reducing their combined amplitude in the FT. Thus, a crucial result is that the V–V dimerization, although reduced, is nevertheless retained in the gated state. Moreover, the average V–V distance in the c direction normal to the film planes increases by a much larger amount than is found by diffraction that could indicate rotation of the VO6 octahedra. On the other hand, the V–V distance within the ab plane (∼3.5 Å) changes little on gating (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the structure in the plane is largely unaffected, consistent with the X-ray diffraction data in Fig. 3C.

Our in situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) and XAS measurements clearly indicate a giant expansion of the VO2 unit cell that is clearly inconsistent with the formation of the rutile phase that the thermally induced metallic phase exhibits. Moreover, we find these reversible structural changes only in films in which channels formed from chains of edge-sharing VO6 octahedra do not lie in the plane of the films, strongly suggesting that these channels are the paths along which the gate-induced oxygen migration takes place. These gate-induced changes in structure and conductivity are likely to be common to many ionic liquid gated systems, opening the way to a potential future of “liquid electronics.”

Methods

Single-crystalline VO2 films were deposited from polycrystalline VO2 sintered targets by pulsed laser deposition. Single-crystalline rutile TiO2 substrates with (001), (101), (100), and (110) orientations were used to provide differently faceted surfaces for VO2 growth. The oxygen pressure of 10 mTorr and the growth temperature of 400 °C for TiO2 (001) and TiO2 (101) and 500 °C for TiO2 (100) and TiO2 (110), respectively, were found to be optimal to yield the largest resistance change across the MIT. Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, reflection high-energy electron diffraction, and atomic force microscopy were used to characterize the films. (See SI Appendix for details).

Device T: Three-terminal devices in lateral gate geometry were fabricated by standard optical lithographic techniques. First, the channel areas (∼100 × 20 µm2) were defined by depositing 30 nm SiO2 dielectric. Electrical contacts to the channel were formed from a bilayer of 5-nm-thick Ru–65-nm-thick Au in a second lithography step. Next, the contacts outside the channel area were covered by 50 nm SiO2 dielectric to prevent any possible interaction between the IL and the Au contact electrodes. Finally, in a fourth lithographic step, a 5-nm Ru–65-nm Au bilayer was deposited to form the gate electrode (1,000 × 1,000 µm2).

Device X: 1 × 10-mm2 electrical contacts to two edges of the 10 × 10 mm2 VO2 film were formed from 5-nm Ru–65-nm Au bilayers that were deposited by using an ∼8 × 10-mm2 aluminum foil shadow mask.

We used the ionic liquid, 1-Hexyl-3methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)-imide (HMIM-TFSI, EMD Chemicals), for all IL gating experiments. To remove any water contamination, the IL and the devices were separately baked at 120 °C in high vacuum (10−7 torr) for several hours. The gating experiments on device T were carried out using a Quantum Design DynaCool at a pressure of a few mTorr of He.

The gating experiments on device X were conducted in specially designed X-ray cell fabricated from Kel-f (shown in Fig. 1B) capable of gating the entire 8 × 10-mm2 VO2 film. Gold wires were pressed down on to the source and drain contacts to electrically connect them to the gating electronics. To avoid influence of water or oxygen during the in situ gating experiments, the X-ray cell was sequentially pumped and purged with dry N2 several times before injecting the baked IL into the cell. The X-ray cell was surrounded by a secondary loose-fitting Kapton enclosure which was continuously purged by dry N2 during the X-ray measurements to ensure that no ice was formed on the surface of the membrane when the cell was cooled to below room temperature. Note that the X-ray cell is a closed cell in which any oxygen which leaves the VO2 device is retained within the IL because the IL is contained within a vacuum-tight membrane formed from a sealed 7.5-µm-thick Kapton sheet.

XRD data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) on beam line 7–2. A Si(111) monochromated X-ray beam with an energy of 12,000.89 eV, as determined from multiple reflections from a LaB6 crystal, and focused to a spot size of 118 × 374 µm2, was used for these measurements. The IL gating cell was mounted on a Huber goniometer head, which was attached to the SSRL’s Huber 6+2 circle diffractometer. A Si(111) analyzer crystal with a scintillation counter was used to detect only the elastically diffracted X-rays. Both ISD and IG were monitored during the XRD measurements. The film thickness and its out-of-plane lattice parameter were extracted from the θ–2θ scans using Bruker DIFFRACplus LEPTOS 7 and TOPAS 4.2 software, respectively.

X-ray absorption spectra were measured at the SSRL on beam line 11–2. The sample was oriented at 45° relative to the linearly polarized X-ray beam and detector so that the spectra are a mixture of the normal and in-plane structures. Measurements were performed in the fluorescence mode using a 100-element monolithic Ge detector and X-ray Instrumentation Associates digital amplifiers windowed on the V Kα emission. Two separate spectra were collected for each state and compared before averaging. Si(220) crystals were used to monochromatize the X-ray beam. Harmonic rejection was accomplished by a Rh-coated float glass mirror tilted to have a cutoff energy of 9–10 keV, allowing the monochromator to be run fully tuned to minimize jitter. The X-ray photon energy was calibrated by assigning the position of the peak corresponding to the V 1s → 4p transition to 5,488.5 eV (in a vanadium oxide standard). The reduction of the EXAFS data was performed using standard procedures that are described in detail within SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Juana Acrivos for discussions and encouragement. Support for D.P. from the Graduate School “Material Science in Mainz” (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, GSC 266) is gratefully acknowledged. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of Standford Linear Accelerator Center National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Stanford University. S.D.C. is supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, DOE, under the Heavy Element Chemistry Program and the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1419051112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ahn CH, et al. Electrostatic modification of novel materials. Rev Mod Phys. 2006;78(4):1185–1128. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee M, Williams JR, Zhang S, Frisbie CD, Goldhaber-Gordon D. Electrolyte gate-controlled Kondo effect in SrTiO3. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107(25):256601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.256601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M, Graf T, Schladt TD, Jiang X, Parkin SSP. Role of percolation in the conductance of electrolyte-gated SrTiO3. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109(19):196803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.196803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueno K, et al. Discovery of superconductivity in KTaO3 by electrostatic carrier doping. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(7):408–412. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye JT, et al. Superconducting dome in a gate-tuned band insulator. Science. 2012;338(6111):1193–1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1228006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhoot AS, et al. Increased T(c) in electrolyte-gated cuprates. Adv Mater. 2010;22(23):2529–2533. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leng X, Garcia-Barriocanal J, Bose S, Lee Y, Goldman AM. Electrostatic control of the evolution from a superconducting phase to an insulating phase in ultrathin YBa2Cu3O(7-x) films. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107(2):027001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.027001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imada M, Fujimori A, Tokura Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev Mod Phys. 1998;70(4):1039–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oka T, Aoki H. 2009. Nonequilibrium quantum breakdown in a strongly correlated electron system. Lecture Notes in Physics: Quantum and Semi-Classical Percolation and Breakdown in Disordered Solids, eds Sen AK, Bardhan KK, Chakrabarti BK (Springer, Heidelberg), Vol 762, pp 251–285.

- 10.Cavalleri A, Dekorsy T, Chong HHW, Kieffer JC, Schoenlein RW. Evidence for a structurally-driven insulator-to-metal transition in VO2: A view from the ultrafast timescale. Phys Rev B. 2004;70(16):161102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu M, et al. Terahertz-field-induced insulator-to-metal transition in vanadium dioxide metamaterial. Nature. 2012;487(7407):345–348. doi: 10.1038/nature11231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin FJ. Oxides which show a metal-to-insulator transition at the Neel temperature. Phys Rev Lett. 1959;3(1):34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McWhan DB, Remeika JP. Metal-insulator transition in (V1-xCrx)2O3. Phys. Rev. B. 1970;2:3734–3750. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodenough JB. Anomalous properties of the vanadium oxides. Annu Rev Mater Sci. 1971;1(1):101–138. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mott NF. Metal Insulator Transitions. 2nd Ed Taylor & Francis; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyert V. The metal-insulator transitions of VO2: A band theoretical approach. Ann Phys (Leipzig) 2002;11:650–702. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodenough JB. The two components of the crystallographic transition in VO2. J Solid State Chem. 1971;3(4):490–500. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano M, et al. Collective bulk carrier delocalization driven by electrostatic surface charge accumulation. Nature. 2012;487(7408):459–462. doi: 10.1038/nature11296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong J, et al. Suppression of metal-insulator transition in VO2 by electric field-induced oxygen vacancy formation. Science. 2013;339(6126):1402–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.1230512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samant MG, Toney MF, Borges GL, Blum L, Melroy OR. Grazing incidence x-ray diffraction of lead monolayers at a silver (111) and gold (111) electrode/electrolyte interface. J Phys Chem. 1988;92(1):220–225. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parratt LG. Surface studies of solids by total reflection of X-rays. Phys Rev B. 1954;95:359–369. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong J, Lytle FW, Messmer RP, Maylotte DH. K-edge absorption spectra of selected vanadium compounds. Phys Rev B. 1984;30(10):5596–5610. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee PA, Citrin PH, Eisenberger P, Kincaid BM. Extended x-ray absorption fine structure—its strengths and limitations as a structural tool. Rev Mod Phys. 1981;53(4):769–806. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehr JJ, et al. Ab initio theory and calculations of X-ray spectra. C R Phys. 2009;10(6):548–559. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.