Abstract

Aims

Although multiple recent studies have confirmed an association between chronic proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use and hypomagnesemia, the physiologic explanation for this association remains uncertain. To address this, we investigated the association of PPI use with urinary magnesium excretion.

Methods

We measured 24-hour urine magnesium excretion in collections performed for nephrolithiasis evaluation in 278 consecutive ambulatory patients and determined PPI use from contemporaneous medical records.

Results

The mean daily urinary magnesium was 84.6±42.8 mg in PPI users, compared to 101.2±41.1 mg in non-PPI users (p=0.01). In adjusted analyses, PPI use was associated with 10.54±5.30 mg/day lower daily urinary magnesium excretion (p=0.05). Diuretic use was associated with increased magnesuria, but did not significantly modify the effect of PPI on urinary magnesium. As a control, PPI use was not associated with other urinary indicators of nutritional intake.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that PPI use is associated with lower 24-hour urinary magnesium excretion. Whether this reflects decreased intestinal uptake due to PPI exposure, or residual confounding due to decreased magnesium intake, requires further study.

Keywords: electrolytes, hypomagnesemia, magnesium, proton-pump inhibitors

Introduction

Although proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are generally considered safe and are available without a prescription, recent data has linked their use to an array of adverse effects, including respiratory infections,1 renal failure,2,3 Clostridium difficile colitis,4,5 hip fractures,6 and drug-drug interactions.7 PPI-associated hypomagnesemia, associated with seizures, tetany, and increased cardiovascular mortality, was initially reported in several small case reports and case series, 8–12 culminating in a U.S. Food and Drug Administration “drug safety communication” in March 2011.13 Recent observational data suggest that the association of PPI use with lower serum magnesium levels is restricted to those concurrently taking diuretics14 rather than a general population.15 These observations suggest a “second hit” phenomenon, where the additive effect of PPI exposure to diuretic-induced urinary wasting results in magnesium depletion.

The mechanistic explanation of the association between PPI use and hypomagnesemia is not fully known. Magnesium is primarily absorbed in the small intestine, stored in bone, and excreted in excess by the kidney. Initial studies have suggested that PPI use inhibits intestinal magnesium absorption, likely by interfering with paracellular magnesium transport across intestinal epithelium.16-17 The preponderance of case reports have documented low urinary magnesium excretion in PPI-associated hypomagnesemia.

To further explore the mechanism of PPI-induced hypomagnesemia, we evaluated the association of PPI use and 24-hour urine magnesium excretion in ambulatory patients undergoing routine evaluation of nephrolithiasis. Given that urine collections performed as part of an initial nephrolithiasis evaluation in non-hospitalized patients likely reflect a stable nutritional state, along with the low urinary magnesium demonstrated in prior case reports of PPI-associated hypomagnesaemia, we hypothesized that 24-hour urine magnesium excretion would be lower in PPI users than non-PPI users.

Subjects and Methods

Study Population

All consecutive patients seen at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center outpatient nephrology clinic between March 2001 and November 2012 who had a 24-hour urine metabolic analysis sent to LabCorp’s LithoLink® as part of a nephrothialiasis evaluation were included. Of these, 7 were missing comorbidity data and 2 were missing urinary magnesium concentrations, leaving a total sample size of 278 unique individuals. Only first urine collections were included. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Medication exposure

The primary exposure was use of PPI within the three month period prior to 24-hour urine collection. Medication exposure was determined by electronic chart review of progress notes and medication records. To evaluate confounding by indication, H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) exposure was also included.

Outcome

The primary outcome was total 24-hour urinary magnesium, determined as the product of 24-hour urine volume and urinary magnesium concentration.

Covariates

Since PPI are often used for dyspepsia, and this condition may influence diet, we included multiple urinary indicators of nutritional intake to minimize residual confounding. These components of the urinary metabolic analysis that represent nutritional intake include oxalate, potassium, ammonium, uric acid and the protein catabolic rate (an assessment of dietary protein intake). A history of diabetes was included given its association with both PPI use and magnesium.18 Diuretic use was included given its magnesuric effect. Serum creatinine was also included since PPI exposure can cause renal dysfunction and this can lead to alterations in magnesium excretion. We used age and gender to impute means for the missing values for weight (n = 10) and protein catabolic rate (n = 10).

Statistical analysis

We present baseline characteristics stratified by PPI exposure in Table 1. Binary indicator variables were created for PPI, H2RA, and diuretic use as well as diabetes history. Sequential multivariate regression was used to determine the effect of PPI on 24-hour urinary magnesium. Model 1 included age and gender. Model 2 added diabetes, weight, diuretic use, and the 24-hour urinary indices influenced by dietary intake: potassium, ammonium, oxalate, creatinine, uric acid, and protein catabolic rate. Model 3 included serum creatinine, though 45 patients were missing this data. Given the direct effect of diuretic use on magnesium excretion, we tested for effect modification of PPI use and urinary magnesium relationship by diuretic exposure, and further stratified by diuretic exposure. To test the specificity of our analysis, urinary potassium, oxalate, and protein catabolic rate were used as dependent variables in separate multivariable analyses. All analyses were performed using JMP Pro (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, stratified by proton pump inhibitor use

| PPI (n = 50) | No PPI (n = 228) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.6 (11.9) | 55.0 (14.4) | 0.002 |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 80.6 (19.2) | 78.8 (18.5) | 0.54 |

| Gender, % female | 44.0 | 46.5 | 0.75 |

| Systolic BP, mean (SD), mmHg | 122 (34) | 112 (42) | 0.09 |

| Diuretic use, n (%) | 9 (18.0) | 45 (19.7) | 0.77 |

| H2 receptor antagonist use, n (%) | 5 (10.0) | 9 (4.0) | 0.10 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 12 (24.0) | 39 (17.1) | 0.27 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 13 (26.0) | 36 (15.8) | 0.10 |

| Serum creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dla | 1.09 (0.44) | 1.18 (0.56) | 0.27 |

| FeMg, mean (SD), %b | 3.70 (1.94) | 3.49 (2.24) | 0.71 |

| 24-hour urinary measurements, mean (SD) | |||

| Volume, L/day | 2.0 (0.91) | 2.1 (0.91) | 0.33 |

| Calcium, mg/day | 170.1 (132.7) | 204.5 (124.7) | 0.08 |

| Creatinine, mg/day | 1481.1(558.5) | 1571.2(546.0) | 0.29 |

| Oxalate, mg/day | 39.7 (22.8) | 37.8 (17.3) | 0.52 |

| Citrate, mg/day | 442.8 (331.8) | 530.7 (320.2) | 0.08 |

| Uric acid, g/day | 0.54 (0.19) | 0.63 (0.25) | 0.02 |

| Ammonium, mmol/day | 33.5 (19.3) | 35.1 (7.0) | 0.56 |

| Sodium, mmol/day | 143.4 (66.3) | 163.0 (81.5) | 0.11 |

| Potassium, mmol/day | 66.1 (27.4) | 65.0 (25.5) | 0.78 |

| Chloride, mmol/day | 146.9 (58.3) | 161 (71.9) | 0.19 |

| Urea nitrogen, g/day | 11.1 (4.1) | 12.1 (4.6) | 0.13 |

| Protein catabolic rate, g/kg/day | 1.07 (0.35) | 1.16 (0.34) | 0.11 |

Serum creatinine was not available for 45 subjects analyzed.

FeMg = Fractional excretion of magnesium; serum magnesium was not available for 167 subjects analyzed.

Results

Patient Admission Characteristics

PPI use was documented in 18% (n=50) of all study subjects, while H2RA were used by 5% (n = 15). As seen in Table 1, PPI users were older, but had similar prevalence of chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and diuretic use. Overall nutritional intake, as determined by urinary nutritional indicators, was similar in those with and without PPI use.

Association of PPI use with 24-hour urinary magnesium

Unadjusted mean 24-hour urine magnesium was 84.6±42.8 mg/day in PPI users and 101.2±41.1 mg/day in non-PPI users (p=0.01). In adjusted analysis, including standard measures of nutritional intake, PPI use remained significantly associated with lower urinary magnesium, with an almost 11 mg lower 24-hour urinary magnesium (p=0.05). As demonstrated in Table 2, H2RA use was not associated with 24-hour urinary magnesium in either adjusted or unadjusted analysis, although the small number of individuals limits the power to detect a difference.

Table 2.

Association of PPI and H2-receptor antagonist use and 24-hour urinary magnesium

| Proton-pump inhibitors | H2-receptor antagonists | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Mg (β-coefficient ± SE) |

p-value | Urinary Mg (β-coefficient ± SE) |

p-value | |

| Unadjusted model | −16.55 ± 6.52 | 0.01 | 1.00 ± 11.45 | 0.93 |

| Model 1a | −12.13 ± 6.31 | 0.06 | 5.23± 10.94 | 0.63 |

| Model 2b | −10.54 ± 5.30 | 0.05 | −0.17 ± 9.21 | 0.99 |

| Model 3c | −10.73 ± 5.42 | 0.05 | −0.43 ± 9.09 | 0.96 |

Model 1 includes age and gender.

Model 2 includes Model 1 and weight, history of diabetes, diuretic use, and urinary potassium, ammonia, oxalate, creatinine, uric acid and protein catabolic rate.

Model 3 includes Model 2 and serum creatinine (with 45 subjects missing data)

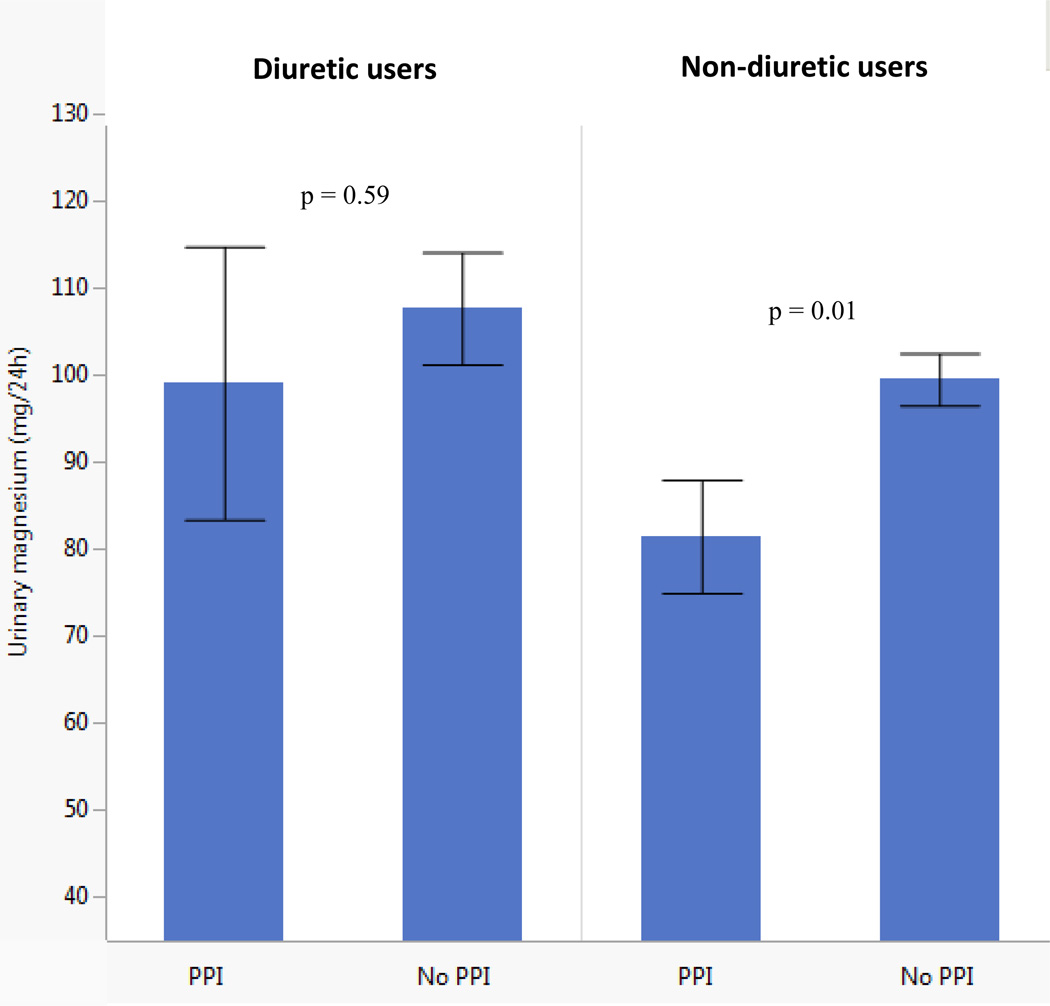

A total of 19% (n = 54) of study subjects were prescribed diuretics, mainly (79%) thiazides. Diuretic use did not alter the association of PPI exposure with urinary magnesium excretion (P value for multiplicative interaction term 0.83). As expected, given the effect of diuretics on renal sodium and magnesium handling, diuretic users had more daily magnesium excretion than non-diuretic users. Amongst diuretic and non-diuretic users, PPI use was associated with lower 24-hour urine magnesium excretion than non-PPI users (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Urinary magnesium in PPI and non-PPI users, stratified by diuretic use.

P-values calculated from ANOVA measuring difference in means of urinary magnesium between PPI and non-PPI users, within each stratification of diuretic use.

Association of PPI use with 24-hour urinary potassium, oxalate, and protein catabolic rate

As controls, we performed separate regressions on 24-hour urinary potassium, oxalate, and protein catabolic rate, as indicators of generalized nutritional intake. PPI use was not associated with any outcome (p=0.37, p=0.32, and p=0.59, respectively).

Discussion

In this sample of 278 consecutive patients undergoing 24-hour urine collection for nephrolithiasis, PPI use was associated with lower 24-hour urinary magnesium excretion.

Given the assumption that urinary magnesium excretion reflects magnesium intake in the steady state, decreased urinary magnesium likely reflects decreased intake or absorption. Since other markers of dietary nutrition did not vary by PPI exposure, our data suggests that PPI use may decrease intestinal magnesium absorption.

We found that daily adjusted magnesium excretion was almost 11 mg lower in PPI users than non-users. Although we do not have information regarding magnesium dietary intake, PPI use was not significantly associated with other urinary indices of nutrition, suggesting that the association is unlikely to be due to differences in dietary intake. Furthermore, H2 receptor antagonist use was not associated with differences in urinary magnesium. Together, these findings support a class effect of PPIs on intestinal magnesium absorption.

As expected, diuretic use was associated with increased magnesium excretion. However, in both diuretic and non-diuretic users, PPI users tended to have lower urinary magnesium. These findings support a potential “second hit” phenomenon, where the combination of decreased intestinal absorption due to PPI use and renal magnesium wasting due to diuretics may result in magnesium depletion and frank hypomagnesemia.

Our study was limited by the unavailability of serum magnesium concentrations. However, as previously shown, 14 the effect of PPI therapy on serum magnesium is small, and it is highly unlikely that PPI therapy was associated with significant changes in serum magnesium in our small sample size. Moreover, since magnesium is primarily an intracellular cation stored within the skeleton, serum magnesium likely does not accurately reflect magnesium homeostasis, and more sophisticated diagnostic methods, such as magnesium infusion testing, are required to characterize magnesium stores. In addition, the primary purpose of this analysis was not to describe body magnesium content, but rather to characterize daily magnesium balance.

In addition, our study was limited by its relatively small size, and inability to characterize the variability of urinary magnesium excretion. However, in a subgroup analysis of 123 patients with repeat 24-hour urine studies, we found a mean urinary magnesium difference of −1.92 mg/24 h (SD 45.38), reflecting similar magnesium excretion between collections.

In addition, although the chronicity of PPI use influences the risk of hypomagnesemia, we could not reliably document the length of PPI exposure. While our medical record system does allow for some documentation of over-the-counter medications, it is also possible that some subjects did not report their use of PPIs to their physicians, leading to an underestimation of PPI use and possibly an underestimation of the true effect of PPI use on magnesium excretion. Furthermore, since our study is a non-random sampling of patients undergoing a nephrolithiasis evaluation, our findings may not be generalizable to a broader population. Finally, although we included other measures of dietary intake, it is plausible that PPI users consumed less magnesium.

In summary, PPI use is associated with lower urinary magnesium excretion, adding physiologic basis to the observation that chronic PPI use is associated with hypomagnesemia. Whether the observed association reflects residual confounding will require further well-designed studies. Until that point, our results support the FDA advisory suggesting that PPI use can lead to hypomagnesemia in susceptible individuals.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NCRR and NCATS, NIH Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. Drs. William and Danziger had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Funding / Conflict of Interest: The authors have no relevant funding or competing interests to disclose.

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: William, Danziger

Acquisition of data: Nelson, Hayman

Analysis and interpretation of data: William, Danziger, Mukamal

Drafting of the manuscript: William, Danziger

Administrative, technical, or material support: Nelson, Hayman

Study supervision: Danziger, William

References

- 1.Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301:2120–2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray S, Delaney M, Muller AF. Proton pump inhibitors and acute interstitial nephritis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sierra F, Suarez M, Rey M, Vela MF. Systematic review: Proton pump inhibitor-associated acute interstitial nephritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham R, Dale B, Undy B, Gaunt N. Proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54:243–245. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(03)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell MD, Novack V, Grgurich P, et al. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:784–790. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulhaber GA, Furlanetto TW. Could magnesium depletion play a role on fracture risk in PPI users? Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1776. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:2051–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackay JD, Bladon PT. Hypomagnesaemia due to proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a clinical case series. QJM. 2010;103:387–395. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoorn EJ, van der Hoek J, de Man RA, Kuipers EJ, Bolwerk C, Zietse R. A case series of proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:112–116. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuipers MT, Thang HD, Arntzenius AB. Hypomagnesaemia due to use of proton pump inhibitors--a review. Neth J Med. 2009;67:169–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein M, McGrath S, Law F. Proton-pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemic hypoparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1834–1836. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc066308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shabajee N, Lamb EJ, Sturgess I, Sumathipala RW. Omeprazole and refractory hypomagnesaemia. BMJ. 2008;337:a425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39505.738981.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs) Drug Safety Communication - Low Magnesium Levels Can Be Associated With Long-Term Use. 03/03/2011. at http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm245275.htm.)

- 14.Danziger J, William JH, Scott DJ, et al. Proton-pump inhibitor use is associated with low serum magnesium concentrations. Kidney Int. 2013;83:692–699. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koulouridis I, Alfayez M, Tighiouart H, et al. Out-of-Hospital Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Hypomagnesemia at Hospital Admission: A Nested Case-Control Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thongon N, Krishnamra N. Omeprazole decreases magnesium transport across Caco-2 monolayers. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1574–1583. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cundy T, Mackay J. Proton pump inhibitors and severe hypomagnesaemia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:180–185. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833ff5d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbagallo M, Dominguez LJ. Magnesium metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;458:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]