Abstract

Mammary gland analog secretary carcinoma (MASC) of salivary gland is typically a tumor of low histologic grade and behaves as a low-grade malignancy with relatively benign course. This tumor shares histologic features, immunohistochemical profile, and a highly specific genetic translocation, ETV6-NTRK3, with secretory carcinoma of breast. Histologically, it is often mistaken as acinic cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified, and other primary salivary gland tumors. Here we report a case of MASC with high-grade transformation and cervical lymph node metastases confirmed with ETV6-NTRK3 translocation arising in the hard palate of a 41 year-old adult. Interestingly, the metastatic carcinoma has lower grade than the original tumor which strongly support malignant transformation of the original tumor. Most commonly, MASC arises from the parotid gland and less often in minor salivary glands. Metastasis is relatively uncommon and high-grade histology has only been reported in four cases with three of them arising from the parotid gland and the location of the fourth one has not been reported. This is the first case with high grade histology that arise from minor salivary gland and it emphasizes the importance of molecular screening of salivary gland tumor with high-grade histology for ETV6-NTRK3 translocation. In our literature of 115 cases that includes the current case, MASC occurred predominantly in adult with only a few cases under 18 years of age and a male to female ratio of 1.2:1. Parotid gland is more commonly affected but there is also significant occurrence in minor salivary glands. Except for the cases with high grade histology, the overall prognosis is good.

Keywords: Analog secretary carcinoma, salivary gland, high grade, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a recently recognized malignancy arising in salivary glands [1] with striking resemblance to secretory carcinoma of the breast. MASC and secretory carcinoma of the breast (SCB) share the common feature of a balanced translocation, t(12;15)(p13;q25) creating a ETV6-NTRK3 fusion [1]. Both MASC and SCB are immunoreactive for S100, epithelial membrane antigen, mammoglobin, and vimentin and are “triple negative” (non-immunoreactive for estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor and negative for Her2/Neu mutation) [1-3]. While MASC is an indolent tumor, SCBs that occur in children are also indolent in nature. MASC has joined the ranks of salivary gland tumors, along with pleomorphic adenoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma, that occurs also in breast [4].

To this date, over 100 cases have been reported in the literature [1,5-26]. Except for the few cases that are reported in adolescents, the majority occurred in adults with painless mass involving the parotid as the most common presentation. MASC is typically a low-grade malignancy with low-grade histopathologic features. However, due to its rather non-specific histopathologic features, MACS can be easily be mistaken with primary adenocarcinoma and acinic cell carcinoma. Differentiation of MASC from its mimickers is important due to their differences in behavior.

Here, we report a case that occurred in the palate, an unusual location for MASC, with high-grade transformation and metastases to cervical lymph nodes. MASC with high-grade histology is rare and only 4 case has been reported [19,25] to this date with three of them arising from the parotid gland and the location of the fourth has not been documented. This is the first case of MASC with high-grade transformation arising in minor salivary glands. It further emphasizes the importance of immunohistochemical profiling and molecular pathology screening in an otherwise non-suspicious carcinoma arising from the salivary glands. This report is accompanied with a literature review.

Case presentation

A 41 year-old female presented with a one year history of painful ulcer in her hard palate. Physical exam revealed a 2 cm ulcerated crater located in her left palate at the junction between her hard and soft palates with minimal surrounding induration, and a firm, enlarged left cervical lymph node. The patient did not have any other significant comorbidities or constitutional manifestations. There was no clinical or imaging evidence of distant metastasis.

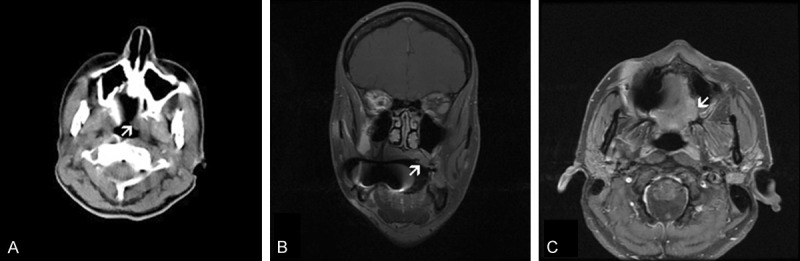

No significant bone erosion was demonstrated by computer assisted tomography (CT) (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) identified a 1.8 × 1.7 × 1.8 cm mildly enhanced centrally ulcerative lesion at the left posterior aspect of her hard palate with minimal surrounding edema (Figure 1B, 1C). The lesion extended laterally to the maxillary buttress and immediately adjacent to what appeared to be inflammatory changes of the mucosa of the left maxillary sinus. Posterior edge of the lesion extended to the greater palate foramina but there was no convincing imaging evidence of perineural spread proximal to that location. A pathologically enlarged left level IIa lymph node, 2.4 × 1.5 cm, and an enlarged right level IIa lymph node, 1.8 cm, were identified. There were prominent but not significant (by MRI size criteria) lymph nodes at left level Ib and bilateral level IIb. There was also a prominent superficial node of the left parotid that was thought likely to be reactive.

Figure 1.

Clinical imaging: The lesion (arrow) has no significant bone erosion on CT scan (A). Coronal (B) and T1-weighted axial (C) MRI demonstrated a lesion that has thickened the palate and accompanied by reactive inflammatory changes in the left maxillary sinus.

A biopsy was performed in an outside hospital followed by left wide excision of left palate with partial maxillectomy and ipsilateral neck dissection. The patient was treated by radiation therapy and was disease free 10 months after the resection.

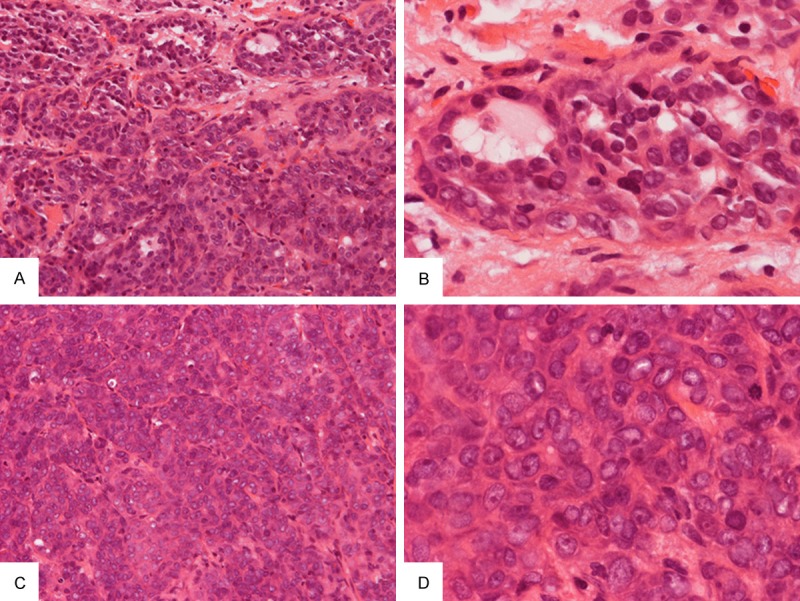

The tumor in the biopsy specimen was composed of two contrasting areas. At the edge of the lesion were small amount of neoplastic epithelial proliferation with gland formation containing pale eosinophilic secretion (Figure 2A and 2B). The tumor cells in this area had eosinophilic cytoplasm and small to medium sized nuclei without prominent nucleoli. The bulk (approximately over 80%) of the tumor was composed of solid proliferation of neoplastic epithelial cells arranged in cords and trabeculae separated by delicate fibrovascular septa. No gland formation was noted in these areas (Figure 2C). In contrast to the areas with glandular formation, the nuclei in solid areas were large and contain prominent nucleoli (compare Figure 2D and 2B). The solid area closely mimicked an adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (ANOS). Perineural invasion and lymphovascular invasion were also identified. Immunohistochemistry showed focally positive immunoreactivity for mammoglobin in the glandular area. Tumor cells also demonstrated diffuse positivity with AE1/3, CK7, S-100, and vimentin. The tumor cells were weakly immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen, polyconal carcinoembryonic antigen, CD117, synaptophysin, and CD56. DOG-1 is focally and weakly immunoreactive. P63, glial fibrillary acidic protein, smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, myosin heavy chain, caldesmon, and melan-A were negative. MIB-1 proliferative index ranges from 10 to 20%. Please refer to Table 1 for details of the antibodies used in this study. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) confirmed ETV6-NTRK3 fusion. A diagnosis of MASC with high-grade changes was made.

Figure 2.

Biopsy specimen: A few small neoplastic glands with pale eosinophilic secretion are present at the periphery of the tumor (A) and the tumor cells have small to medium sized nuclei without prominent nuclei (B). The bulk of the neoplastic component is composed of solid cords and trabeculae of cells separated by thin fibrous septa (C). The nuclei are enlarged and contain prominent nucleoli (D) in contrast to those with gland formation as illustrated in (B). Original magnification in (A) and (C) is 20×, in (B) and (D) is 60×.

Table 1.

Antibody used in this study

| Antibody | Clone | Dilution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAF47 | 25 | 1:100 | BD Biosciences |

| Calponin | EP798Y | RTU* | Cell Marque |

| Cytokeratin 5/6 | D5/16B4 | RTU | Ventana |

| Cytokeratin 7 | OV-TL 12/30 | 1:100 | DAKO |

| Cytokeratin 8/18 | 5D3 | RTU | Biocare Medical |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor | 3C6 | RTU | Ventana |

| Epithelial membrane antigen | E29 | RTU | Cell Marque |

| GCDFP-15 | D6 | 1:40 | Covance |

| Ki67 | 30-9 | RTU | Ventana |

| Mammoglobin | 304-1A5, 31A5 | RTU | Zeta Corporation |

| P63 | BC4A4 | RTU | Biocare Medical |

| S100 | Polyclonal | RTU | Ventana |

| Vimentin | 3B4 | RTU | Ventana |

| P53 | Bp53-11 | RTU | Ventana |

| Beta-catenin | 14 | RTU | Cell Marque |

| Ki67 | 30-9 | RTU | Ventana |

RTU: Ready to use pre-diluted anitbodies as supplied by the vender.

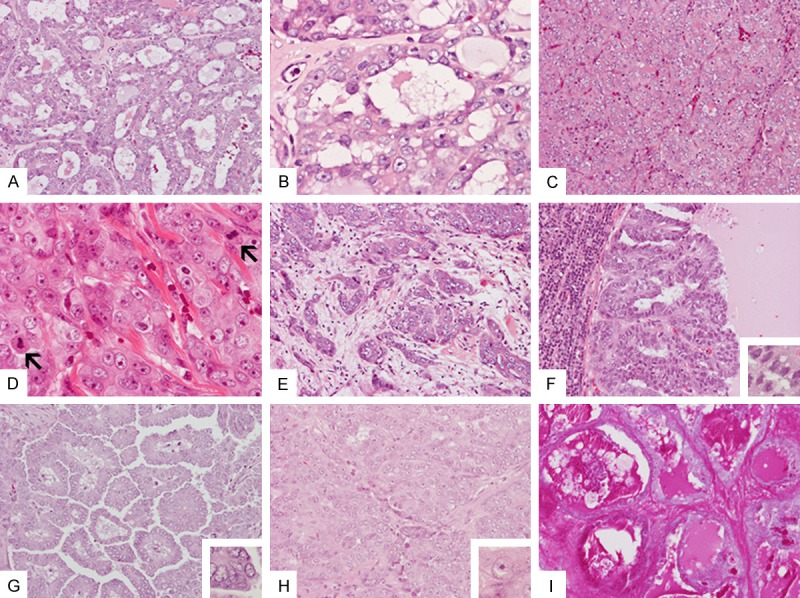

Similar to the biopsy material, the bulk of the tumor in the resection specimen is composed of solid neoplastic epithelial proliferation with a minor component with neoplastic glands and microcysts at the periphery that contained pale eosinophilic secretion (Figure 3A). In contrast to the biopsy specimen, enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli were noted in the glandular epithelial cells (Figure 3B). The solid component was composed of solid cords and nests of neoplastic cells separated by a variable amount of fibrotic tissue containing delicate blood vessels (Figure 3C and 3D). The tumor cells were mitotically active (Figure 3D). Bone erosion and perineural invasion were also identified. The tumor cells were featured by a moderate amount of amphophilic to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with high-grade nuclei. Irregular invading islands of neoplastic cells accompanied by desmoplastic reactions were noted in some areas (Figure 3E). Necrosis was not readily seen.

Figure 3.

Resection specimen: Areas with neoplastic gland formation (A) are noted mainly at the periphery of the tumor. These glands contain small amount of pale eosinophilic secretion (B). The bulk of the tumor is solid and is composed of cords or nests of cells with high-grade nuclei with prominent nucleoli separated by thin fibrous septa with delicate blood vessels (C and D). Multiple mitoses are present (arrows in D). Infiltrating tumor with desmomplastic reaction is also noted (E). Histology of the metastasis to cervical lymph nodes includes cystic (F) growth pattern (G) with low-grade nuclei (inset in F), papillary growth pattern (G) with low-grade nuclei (inset in G), and solid areas (H) with high-grade nuclei (inset in H). Secretions in the areas are strongly positive for PAS stain (I). Original magnification in (A, C, E-I) and is 20×; in (B), (D), and insets in (F), (G), and (H) is 60×.

Metastatic foci ranging from 0.2 to 3.9 cm were identified in three cervical lymph nodes. Interestingly, the metastases contained areas with both high-grade and low-grade nuclei. In addition, the metastases contained both cystic (Figure 3F) and papillary growth patterns (Figure 3G) with low-grade nuclei. These components were not present in the primary tumor. In addition, solid area with high-grade nuclei (Figure 3H) and areas with gland formation classic for MASC but with high grade nuclei similar to those in the primary tumor were also present in the metastases. Secretions of the neoplastic glands were strongly positive for periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reaction (Figure 3I).

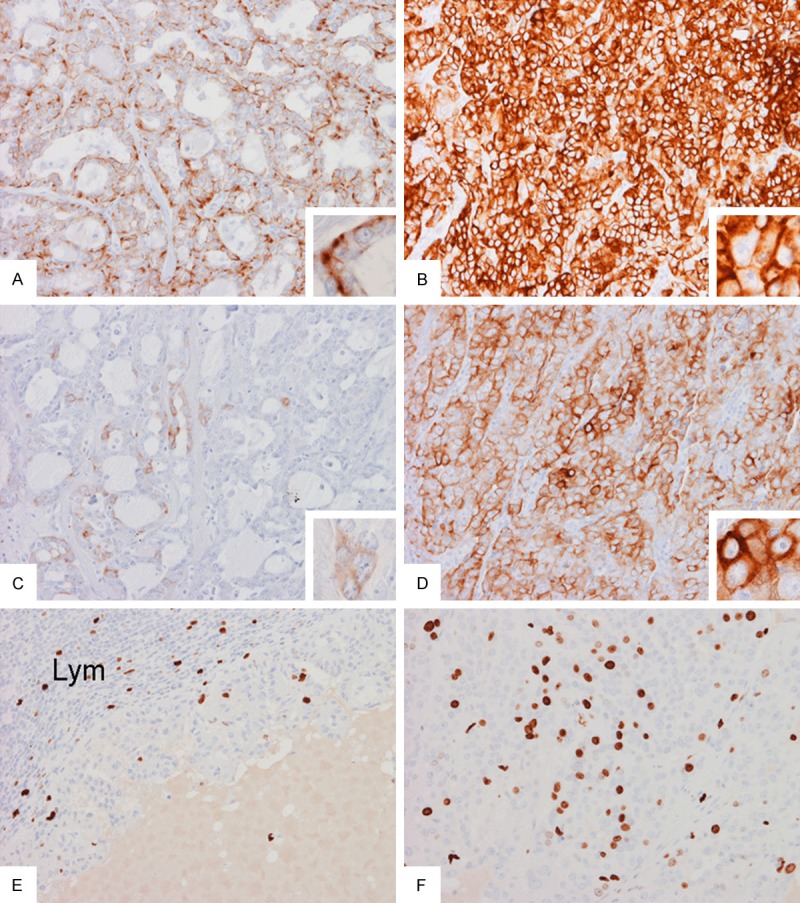

Immunohistochemistry demonstrated different staining patterns between areas with glandular architecture and solid areas. Immunoreactivities of cytokeratin 7 (Figure 4A and 4B) and cytokeratin 8/18 (Figure 4C and 4D) were patchy in areas with glands and microcysts but the expression is diffuse in solid areas. S100, BAF47, and vimentin were diffusely immunoreactive. Similar expression of S100 protein is detected in areas with glands and microcysts and in solid areas. Both components were negative for calponin, cytokeratin 5/6, epithelial membrane antigen, GCDFP-15, and p63. Homogeneous membranous pattern of beta-catenin immunoreactivity was noted in both high and low grade areas. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFT) was weakly positive in areas with gland and microcysts but negative in solid areas. In the metastasis where both low- and high-grade areas were present, the Ki67 labeling index is low in the low-grade area with papillary growth pattern (Figure 4E) but high in solid area with high-grade nuclei (Figure 4E). There was no increase in p53 labeling in both low- and high-grade areas. Please refer to Table 1 for details of the antibodies used in this study.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry: Expression of cytokeratin 7 is patchy in areas with gland formation (A) and is mostly found at the base of the lining cells (inset in A) but the expression is diffuse in solid areas (B). Expression of cytokeratin 8/18 is only focal in areas with gland formation (C) but is wide spread in solid areas (D). In the metastasis, the Ki67 labeling index is low in the papillary area (E) but high in the solid areas (F). Original magnification in all panels is 20× and in all insets is 60×.

Discussion

MASC is a recently recognized primary carcinoma arising from salivary glands. It shares with SCB the common features of mammoglobin positive luminal secretion and ETV6-NTRK3 translocation. The patients’ age ranged from 14 to 86 year-old (Table 2). In contrast, a significant portion of SCB occurred in children, adolescences, and young females [27].

Table 2.

Reported cases of MASC§

| Age (year) | Sex | Location | Size (greatest dimension)/Pathologic Features | Reference/Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | F | Hard and soft palate | 1.8 cm/Uncerated mass, predominantly solid with microcystic component, high-grade features present | Current case |

| ATD: PNI+/DI-/M+*, lymphovascular invasion identified | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Oral cavity not specified | 1.8 cm/Macrocstic | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD:PNI-/DI+/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Parotid | 3.0 cm/Solid | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD: PNI-/DI-/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Submandibular | 1.8 cm/Solid | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD: PNI+/DI+/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Oral cavity roof of mouth | 0.5 cm/Solid exophytic polyp | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD: PNI+/DI+/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Oral cavity inner cheek | NA/Mixed solid and cystic | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD: PNI-/DI-/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Parotid | 2.9 cm/Mixed solid and cystic | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD: PNI+/DI-/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 1 | Leg. 1 | Lip | 1.2 cm/Solid | 2012 Connor et al. |

| ATD: PNI+/DI+/N-/M- | ||||

| 37 | F | Parotid, deep lobe | 2.0 cm/Microcystic, cribiform, and tubular, FNA was performed | 2012 Ito et al. |

| ATD: PNI+/DI+/N-/M- | ||||

| Leg. 2 | F | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | Leg. 2 | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 2 | M | NA | All cases were originally diagnosed as AciCC. See Leg. 2 for details. | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| 69 | F | Parotid | 3.0 cm/Microcystic, tubular, papillary, and solid, FNA was performed | 2012 Pisharodi et al. |

| ATD: PNI-/DI: ND/N-/M- | ||||

| 48 | F | Upper lip (submucosal) | 1 cm/Microcystic | 2012 Kratochvil et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 52 | M | Lower lip (submucosal) | 0.7 cm/Cribiform, follicular | 2012 Kratochvil et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 44 | M | Upper lip (submucosal) | 0.3 cm/Microcystic | 2012 Kratochvil et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 34 | F | Upper lip | 1.5 cm/Tubular, follicular, microcystic and macrocystic | 2013 Laco et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: -/M: - | ||||

| 58 | M | Parotid | 2.0 cm/Tubular, follicular, microcystic and macrocystic | 2013 Laco et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: -/M: - | ||||

| 71 | M | Buccal | 1.0 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 25 | F | Hard palate | NA/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 20 | F | Soft palate | 0.9 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 86 | F | Soft palate | 1.0 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 79 | F | Soft palate | 0.7 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 62 | F | Upper lip | 0.3 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 71 | M | Upper lip | 0.6 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 59 | M | Lower lip | 0.9 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 68 | M | Lower lip | 0.5 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 34 | F | Submandibular gland | 0.9 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 36 | F | Submandibular gland | 2.0 cm/Original diagnosis was AciCC, see Leg. 3 for details. | 2013 Bishop et al. |

| 58 | F | Parotid, deep lobe | 2.0 cm/Solid, cribiform, microcystic and macrocystic, FNA was performed | 2013 Sethi et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 53 | M | Parotid | 3.0 cm/Micropapillary, microcystic, and solid, original diagnosis was AciCC | 2013 Pinto et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 29 | M | Parotid | 1.8 cm/Micropapillary, microcystic, and solid, original diagnosis was AciCC | 2013 Pinto et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 61 | F | Parotid | 3.0 cm/Micropapillary, microcystic, and solid, original diagnosis was AciCC | 2013 Pinto et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 51 | F | Bucal mucosa | 1.0 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 44 | F | Parotid | 0.9 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N-/M- | ||||

| 48 | M | Soft palate | 1.5 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| The patient developed metastasis and died of disease 4 after two years after initial diagnosis. | ||||

| 55 | M | Parotid | 5.5 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: +/M: - | ||||

| 34 | M | Parotid | 1.6 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 53 | M | Parotid | 1.5 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 53 | M | Parotid | 3.5 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| The patient has multiple recurrence and died of disease after 6 years | ||||

| 55 | F | Parotid | 1.0 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| Multiple recurrence | ||||

| 26 | M | Parotid | 1.5 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 35 | F | Parotid | 3.0 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 46 | M | Parotid | 1.4 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| 55 | M | Parotid | 4.0 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| 59 | F | Parotid | Size not available/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| 21 | F | Parotid | 2.7 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| 75 | F | Parotid | 0.7 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| 32 | M | Upper lip | 1.0 cm/Leg. 4 | 2010 Skálová et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis at 86 months after diagnosis, no evidence of disease for 27 months after treatment | ||||

| 34 | F | Parotid | 1.0 cm/follicular and microcystic | 2012 Levine et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/M: - | ||||

| Mammoglobin positive, no translocation confirmed by FISH | ||||

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Parotid | Leg. 5 | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Submandibular gland | Leg. 5, originally diagnosed as ANOS | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Submandibular gland | Leg. 5, originally diagnosed as ANOS | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Submandibular gland | Leg. 5, originally diagnosed as ANOS | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Soft palate | Leg. 5, originally diagnosed as ANOS | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Soft palate | Leg. 5, initial diagnosis was MASC | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Soft palate | Leg. 5, initial diagnosis was MASC | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Buccal mucosa | Leg. 5, initial diagnosis was MASC | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Buccal mucosa | Leg. 5, initial diagnosis was MASC | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Base of tongue | Leg. 5, originally diagnosed as ANOS | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| Leg. 5 | Leg. 5 | Upper lip | Leg. 5, initial diagnosis was MASC | 2012 Seethala et al. |

| 71 | F | Soft Palate | Leg. 6 | 2011 Fehr et al. |

| 23 | F | Parotid | Leg. 6 | 2011 Fehr et al. |

| 70 | F | Parotid | Leg. 6 | 2011 Fehr et al. |

| 43 | M | Oral mucosa | Leg. 6 | 2011 Fehr et al. |

| 37 | F | Parotid | 0.5 cm/originally diagnosed as salivary adenoma | 2013 Choisea et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | M | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | F | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | F | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | F | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | F | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| Leg. 7 | F | 11 parotid/2 non-parotid | Leg. 7 | 2013 Jung et al. |

| 51 | F | Parotid | 2.5 cm/FNA performed | 2013 Griffith et al. |

| Reported twice (R03, R12) | ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | |||

| 51 | M | Buccal mucosa | 2.1 cm/FNA performed | 2013 Griffith et al. |

| Reported twice (R03, R12) | ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | |||

| 27 | M | Parotid | 1.0 cm/FNA performed | 2013 Griffith et al. |

| Reported twice (R03, R12) | ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | |||

| 44 | F | Submandibular gland | 1.8 cm/FNA performed | 2013 Griffith et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: +/M: - | ||||

| 23 | F | Parotid | 1.2 cm/FNA performed | 2013 Griffith et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| 66 | M | Parotid | NA/FNA performed | 2013 Griffith et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: - | ||||

| Unknown | M | Parotid | 2.2 cm/originally diagnosed as AicCC | 2012 Choisea et al. |

| 41 | F | Hard palate | 0.4 cm/originally diagnosed as mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 2012 Choisea et al. |

| 36 | M | Submandibular gland | 2.5 cm/Solid, microcystic and macrocystic growth pattern, FNA performed | 2012 Yan et al. |

| 14 | F | Parotid | 3.0 cm/ | 2013 Melin-Aldana et al. |

| ATD: PNI: ND/DI: ND/N: +/M: - (metastasis in a periparotid lymph node) | ||||

| 55 | M | Parotid | 8.0 cm | 2014 Skálová A et al. |

| ATD: PIN: ND/DI: ND/N: -/M: -/high-grade histology | ||||

| Recurred locally 6 years later. | ||||

| 61 | M | Parotid | 4 cm/FNA performed | 2014 Skálová A et al. |

| ATD: PIN+/DI: ND/N+/M+ (single metastatic focus in adipose tissue of the neck) | ||||

| Patient died of disseminated disease after 20 months | ||||

| 73 | M | Parotid | Size is unknown, originally diagnosed as a monomorphic adenoma | 2014 Skálová A et al. |

| Recurrence for 4 times and the patient died 4 years after the primary surgery | ||||

| 43 | F | Submandibular gland | Microcystic, tubular and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 23 | F | Parotid | 1.2 cm/FNA performed | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| Microcyctic and pseudopapillary | ||||

| 34 | F | Periparotid lymph node | Microcystic, macrocystic, solid and papillary | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 76 | F | Parotid | Microcystic, macrocystic, and papillary | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 71 | M | Parotid | Microcystic and macrocystic | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 55 | F | Parotid | Macrocystic and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 16 | F | Parotid | Microcystic and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 22 | M | Parotid | Microcystic, macrocystic and solic | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 26 | M | Parotid | Predominently papillary and pseudopapillary with focal microcystic areas | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 56 | M | Parotid | Papillary, microcystic and macrocystic | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 45 | F | Parotid | Microcystic, macrocystic and focal papillary | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 37 | F | Parotid | Macrocystic and focally microcystic | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 53 | M | Parotid | Microcystic and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 46 | F | Parotid | Microcystic and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 56 | M | Parotid | Microcystic, macrocystic, papillary and pseudopapillary | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 28 | F | Parotid | Microcystic, tubular and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| Unknown | F | Parotid | Microcystic, tubular and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 66 | F | Parotid | Microcystic and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

| 53 | M | Submandibular | Microcystic, macrocystic, tubular and solid | 2014 Shah AA et al. |

Unless otherwised stated in the table, ETV6-NTRK3 translocation is confirmed by FISH;

ATD: At the time of diagnosis; PNI: Perineural invasion; DI: Duct involvement; N: Metastasis to cervical lymph nodes or periparotid lymph node; M: Distant metastasis;

Unless otherwise specified, lymphovascular invasion is described in the original report;

NA: Not available; ND: Not described in original report; FNA: Fine needle aspiration; Leg. 1: In this study, the age range was 14 to 77 years (mean, 40 y) with 6 males and 1 female. Further demographic details were not provided in the original publication. Leg. 2: A total of 10 cases were described (8 males, 2 females). The average age was 45.5 years but detailed distribution of age was not provided. There were metastases in 2 out of the 6 cases who received lymph node dissection. All cases were originally diagnosed as acinic cell carcinoma (AciCC). The locations of the tumors were not provided. Since AciCC is most common in parotid gland, the location of these tumors can be assumed to be predominantly the parotid gland. The status for perineural invasion, ductal involvement, and metastases were not provided in the original report. Leg. 3: Perineural invasion was identified in 1 cases but lymphovascular invasion was not identified. Ductal involvement or metastases were not described in the original report. Leg. 4: These tumors were originally diagnosed as acinic cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, cysadenocarcinoma, and low-grade carcinoma not otherwise specified. Leg. 5: The average age in this study was 45.7 years and a male to female ratio of 1.4:1. The average tumor sizes were 1.9 and 2.5 cm respectively depending on whether it is referral or in-house cases respectively. Four cases showed metastases, three cases showed recurrence, and one of the metastatic case resulted in death from disease. Many of these tumors were diagnosed as AciCC, ANOS, mucin secreting signet ring cell carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Leg. 6: The sizes of tumor and original diagnoses, of these cases were not available in the original report. There was no description of perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, lymph node or distant metastasis in the original report. Leg. 7: The age of the cases in this study ranged from 17 to 76 year-old (average is 46.4) cm. The size ranged from 0.7 to 2.5 cm (average 17.7 cm). This is also the first of four cases with high-grade histology. This study also described 10 cases that possessed histologic features of MASC but no ETV6-NTRK3 translocation and these cases were classified as MASC-mimickers. No immunohistochemistry for mammoglobin was performed in this study.

Up to this date, 134 MASC cases have been reported [1,5-26]. Although a male predilection was initially observed, the incidence is about equally distributed among these 134 reported cases with a male to female ratio of 73:61 [1,5-17,21-25]. It typically presents as a painless mass, typically 0.3 to 8.0 cm, with the duration of disease ranging from a few months to multiple recurrences in durations up to 30 years [5]. It can be well circumscribed or uncircumscribed, with or without cystic changes. Extension into the surrounding parenchyma is uncommon [19]. Among these tumors, 91 occurred in parotid, 11 in submandibular gland, 29 in minor salivary glands, and 2 in unspecified area. Histologically, MASC is characterized by a low-grade neoplastic epithelial proliferation with low-grade nuclei and moderate to ample amount of pink granular cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic vacuoles are not uncommon. The neoplastic cells typically arrange in microcystic, tubular, and, less frequently, solid pattern with PAS positive luminal content and occasional intracytoplasmic mucin [5]. Ductal involvement suggesting a ductal origin has been described [5]. Only 4 cases have been described to harbor high-grade areas indicative of high-grade transformation [19,25]. Comedo type necrosis has been described in these cases.

MASC generally follows the behavior of a low grade malignancy. The overall survival is similar to that of AciCC [16]. Metastasis to lymph nodes, lymphovascular and perineural invasion can occur [25]. Most of the patients live free of disease after treatment. In our literature review, 17 patients experienced local recurrence including the 3 cases reported by Skálová A et al [25], four patients experienced distant metastasis, and only 6 patients died of disease including 2 out of the 3 cases reported by Skálová A et al [25].

Although high-grade transformation or dedifferentiation is rare, it has been reported in four recent case [19,25]. All of the four tumors are composed of two distinctive areas with classic low-grade microcystic appearance in one area and well-demarcated, high-grade solid nests in other areas. Interestingly, one case was originally reported as a dedifferentiation of AciCC [19] and the other as monomorphic adenoma [25].

There are three major highlights of this case that separate it from the previously reported cases with high grade histology. First, it occurred in the hard palate while 3 out of the 4 reported case with high-grade histology occurred in the parotid gland [19,25]. Second, the primary tumor is dominated by high-grade solid component. Third, the metastatic carcinoma in this case, however, has a rich diversification on histology which includes cystic and papillary, cystic and glandular growth pattern with high grade nuclei.

Due to differences in clinical behavior and prognosis from its mimickers, it is important to correctly recognize MASC. MASC is characterized by microcysts with luminal secretion that is positive for PAS and mammoglobin [1]. It can also present with macrocysts, papillary proliferation, or cribriform pattern [6,9,11,16,17,19,20]. Despite the characteristic features of MASC, they can still be confused with other salivary gland tumors. These retrospective studies show that MASC are often misdiagnosed as AciCC or ANOS [7,10,13,17,19,22]. Occasional MASC are diagnosed as signet ring adenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma [16] or even salivary adenoma [1,18]. This makes immunohistochemical profiling and molecular pathology screening an important step in the characterization of salivary gland tumors.

The major mimickers of MASC are AciCC and ANOS. The incidence of AciCC [28] occurs with an even age distribution from the second to seventh decade and occasionally in children and is also the second most common salivary gland tumor arising in children [29]. Over 80% of AciCC occur in the parotid gland follows by intra-oral minor salivary glands and submandibular gland. It is rare in sublingual gland [30]. The incidence in minor salivary gland is higher than submandibular gland. In contrast to AciCC with slight female predominance, MASC has clear male predominance. Histologically, AciCC has a variety of growth pattern, including solid, microcystic, papillary-cystic, and follicular and contains cytologic components including acinic cells, intercalated duct-like cells, vacuolated cells, clear cells, and non specific glandular cells. The histologic pattern overlaps with that of MACS. Acinar and intercalated duct cells are diagnostic and contain cytoplasmic zymogen granules which are PAS positive and diastase resistant. However, they are usually non-reactive to amylase antibody. MASC is otherwise lacking the zymogen granules. One must note that zymogen in high-grade AciCC tumors may not be easily demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and PAS stain and may have significant morphological overlap with MASC. Mammoglobin and the presence of ETV6-NTRK3 translocation are specific markers that distinguish AciCC from MASC. They are usually positive in MASC but negative in AciCC. The features that allow separation of MASC and AciCC are well discussed by Chiosea et al. [7].

The incidence of ANOS is at the fourth to eighth decade with a median age of 67. A male predilection is present. Minor salivary glands are the most common sites (61%) for ANOS followed by parotid (32%) and submandibular (7%) glands. minor salivary glands in palate [31]. Histologically, ANOS is characterized by an infiltrative growth of tumor cells that have glandular or ductal features. They can assume varied patterns including glandular and ductular structures, as well as solid, tubular, nests, islands, and cord-like growth [32]. The overall growth pattern does not resemble any of the named salivary malignancies. Focal findings mimicking specific malignancies may be present but is limited in extent. Extensive presence of specific findings suggests diagnosis of specific malignancy [28,32]. ANOS has collagenized, myxoid or mucinous stroma. Tumor cells have intracytoplasmic mucin which can be stained with mucicarmine staining [32]. Since the 1992 WHO salivary gland tumor classification, the number of ANOS cases generally descreased and now considered “a diminishing group of salivary carcinomas” [31].

Other less common mimickers such as signet ring adenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma [16] or salivary adenoma [18] can be distinguished from MASC through astute histopathologic observations as well as demonstration of the absence of ETV6-NTRK3 translocation.

Although confirmation of the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation is the gold standard in identifying MASC, it is rather costly and time consuming. Demonstration of mammoglobin, S100, and STAT5 by immunohistochemistry is a suitable combination for initial screening purposes [1]. It should note that STAT5 is expressed widely in both MASC and AciCC. S100 expression and mammoglobin positive secretion are present in all the MASC cases being tested including our case. Their use is however hampered by its expression in a significant proportion of other salivary gland tumors including mucoepidermoid carcinoma, pleomorphic adenoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, salivary duct carcinoma, low-grade cysadenocarcinoma, and ANOS [13,17]. MASC lacks zymogen granules which distinguish it from AciCC. However, AciCC especially high-grade AciCC can present as zymogen granule poor tumor [16,33]. DOG1, a marker of salivary acini and intercalated duct differentiation, is positive in all acinic cell carcinoma cases and negative in all three MASC cases published by Andre Pinto [13]. However, it can be positive in MASC [19] and is focally positive in our case. In addition, half of AciCC lacks the positivity [19]. GCDFP-15, an apocrine marker positive in all MASC of the initial report is negative in some reported cases [5,10,19] and our case. Diagnosis will be even more challenging when tumors are mostly composed of high-grade cords or nests. Further study on the sensitivity and specificity of combination of these markers is warranted.

MASC typically behaves as a low-grade malignancy. A higher than AciCC lymph node involvement was observed but fall short of statistical significance [16]. Although rare, aggressive MASC cases do occur. The clinical significance with difference between aggressive appearing MASC and the histologically typical MASC that behaves as a low-grade malignancy is not clear. The percentage of solid area in the specimen has been suggested as one of the markers to predict the clinical behavior of MASC [5], which seems to be true for our case, where a great percentage of high-grade area is associated with an aggressive behavior. However, for cases mainly composed of low grade cystic patterns, different clinical behaviors are also observed [1]. In several markers that we have used, notably cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 8/18, we noticed different staining patterns between the high-grade solid area of our case and the typical area with papillary architecture and cyst formation. These markers are more diffusely expressed in the solid high-grade area than the papillary or cystic areas. The biological significances of these findings are uncertain.

A question remains to be answered is what triggers the dedifferentiation of MASC and what it could possibly mean clinically. The pathway for dedifferentiated salivary tumors is unknown. p53 abnormality and Her2 overexpression or amplification have been reported but the frequency varies by the histologic type [33].

Tumor dedifferentiation is associated with an altered expression of many genes [33,34], possibly including the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation. Although the cause-effect relationship between ETV6-NTRK3 translocation and tumorigenesis in SCB has not been firmly established, murine breast epithelial cells with ETV6-NTRK3 translocation are able to develop orthotopic tumor growth without metastases. The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in these transformed cells, the known effector pathway of ETV6-NTRK3 translocation, has been shown to be activated in an insulin-like growth factor 1- or insulin-dependent manner. Experimental success of blocking this pathway leading to reduced tumor growth by tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the insulin-like growth factor 1 signal pathway suggests the possibilities of using these inhibitors for target therapy [35]. This arena is worth to be further investigated.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our most sincere thanks to the technical assistance provided by the histology laboratory of OU Medical Center.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, Starek I, Geierova M, Simpson RH, Passador-Santos F, Ryska A, Leivo I, Kinkor Z, Michal M. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lae M, Freneaux P, Sastre-Garau X, Chouchane O, Sigal-Zafrani B, Vincent-Salomon A. Secretory breast carcinomas with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene belong to the basal-like carcinoma spectrum. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:291–298. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavassoéli FA, Devilee P, editors. Pathology and Genetics Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pia-Foschini M, Reis-Filho JS, Eusebi V, Lakhani SR. Salivary gland-like tumours of the breast: surgical and molecular pathology. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:497–506. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.7.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connor A, Perez-Ordonez B, Shago M, Skalova A, Weinreb I. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin with the ETV6 gene rearrangement by FISH: expanded morphologic and immunohistochemical spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:27–34. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318231542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito S, Ishida E, Skalova A, Matsuura K, Kumamoto H, Sato I. Case report of Mammary Analog Secretory Carcinoma of the parotid gland. Pathol Int. 2012;62:149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiosea SI, Griffith C, Assaad A, Seethala RR. The profile of acinic cell carcinoma after recognition of mammary analog secretory carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:343–350. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318242a5b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisharodi L. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland: cytologic diagnosis and differential diagnosis of an unreported entity. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:239–241. doi: 10.1002/dc.21766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kratochvil FJ 3rd, Stewart JC, Moore SR. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a report of 2 cases in the lips. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.07.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laco J, Svajdler M Jr, Andrejs J, Hrubala D, Hacova M, Vanecek T, Skalova A, Ryska A. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a report of 2 cases with expression of basal/myoepithelial markers (calponin, CD10 and p63 protein) Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Batista D, Eisele DW, Westra WH. Most nonparotid “acinic cell carcinomas” represent mammary analog secretory carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1053–1057. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182841554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sethi R, Kozin E, Remenschneider A, Meier J, VanderLaan P, Faquin W, Deschler D, Frankenthaler R. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: update on a new diagnosis of salivary gland malignancy. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:188–195. doi: 10.1002/lary.24254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto A, Nose V, Rojas C, Fan YS, Gomez-Fernandez C. Searching for mammary analogue [corrected] secretory carcinoma of salivary gland among its mimics. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:30–37. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine P, Fried K, Krevitt LD, Wang B, Wenig BM. Aspiration biopsy of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of accessory parotid gland: another diagnostic dilemma in matrix-containing tumors of the salivary glands. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:49–53. doi: 10.1002/dc.22886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fehr A, Loning T, Stenman G. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary glands with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1600–1602. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822832c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiosea SI, Griffith C, Assaad A, Seethala RR. Clinicopathological characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Histopathology. 2012;61:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Batista D, Begum S, Eisele DW, Westra WH. Utility of mammaglobin immunohistochemistry as a proxy marker for the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation in the diagnosis of salivary mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1982–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams L, Chiosea SI. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma mimicking salivary adenoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:316–319. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung MJ, Song JS, Kim SY, Nam SY, Roh JL, Choi SH, Kim SB, Cho KJ. Finding and characterizing mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:36–43. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop JA. Unmasking MASC: bringing to light the unique morphologic, immunohistochemical and genetic features of the newly recognized mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:35–39. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffith CC, Stelow EB, Saqi A, Khalbuss WE, Schneider F, Chiosea SI, Seethala RR. The cytological features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: a series of 6 molecularly confirmed cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:234–241. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lei Y, Chiosea SI. Re-evaluating historic cohort of salivary acinic cell carcinoma with new diagnostic tools. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:166–170. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersson F, Lian D, Chau YP, Yan B. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: the first submandibular case reported including findings on fine needle aspiration cytology. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:135–139. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rastatter JC, Jatana KR, Jennings LJ, Melin-Aldana H. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the parotid gland in a pediatric patient. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:514–515. doi: 10.1177/0194599811419044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Majewska H, Laco J, Grossmann P, Simpson RH, Hauer L, Andrle P, Hosticka L, Branzovsky J, Michal M. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with high-grade transformation: report of 3 cases with the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion and analysis of TP53, beta-catenin, EGFR, and CCND1 genes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:23–33. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah AA, Wenig BM, LeGallo RD, Mills SE, Stelow EB. Morphology in Conjunction with Immunohistochemistry is Sufficient for the Diagnosis of Mammary Analogue Secretory Carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0557-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horowitz DP, Sharma CS, Connolly E, Gidea-Addeo D, Deutsch I. Secretory carcinoma of the breast: results from the survival, epidemiology and end results database. Breast. 2012;21:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis G, Simpson RHW. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. Acinic cell carcinoma. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Triantafillidou K, Iordanidis F, Psomaderis K, Kalimeras E. Acinic cell carcinoma of minor salivary glands: a clinical and immunohistochemical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2489–2496. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Acinic cell carcinoma of salivary origin. A clinicopathologic study of 67 cases. Cancer. 1978;41:924–935. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197803)41:3<924::aid-cncr2820410321>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Wang BY, Nelson M, Li L, Hu Y, Urken ML, Brandwein-Gensler M. Salivary adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified: a collection of orphans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1385–1394. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-1385-SANOSA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenig BM. Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagao T. “Dedifferentiation” and high-grade transformation in salivary gland carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(Suppl 1):S37–47. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa AF, Altemani A, Hermsen M. Current concepts on dedifferentiation/high-grade transformation in salivary gland tumors. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:325965. doi: 10.4061/2011/325965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tognon CE, Somasiri AM, Evdokimova VE, Trigo G, Uy EE, Melnyk N, Carboni JM, Gottardis MM, Roskelley CD, Pollak M, Sorensen PH. ETV6-NTRK3-mediated breast epithelial cell transformation is blocked by targeting the IGF1R signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1060–1070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]