Abstract

Objective:

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of disability. Impairment in work function considerably adds to symptom burden and increases the economic impact of this disorder. Our study aimed to investigate the factors associated with work status in MDD within primary and tertiary care.

Method:

We used data from 2 large databases for our analysis—Study 1: the InSight database, a chart review of MDD patients treated by primary care physicians across Canada (n = 986); and Study 2: the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project, a cross-sectional study of mood disorder patients (Canadian data only: n = 274).

Results:

Both studies demonstrated high rates of unemployment and disability (30.3% to 42.1%). Quebec showed the highest rate of unemployment (21%) and British Columbia had the greatest percentage of patients on disability (15%). Employed and unemployed groups were similar based on clinical characteristics; however, unemployed people may have higher age, prevalence of medical comorbidity, and greater likelihood of receiving a benzodiazepine. Increased disability rates were associated with history of childhood abuse, duration of current major depressive episode, comorbidity, benzodiazepine use, as well as greater depression and anxiety severity. The unemployed–disability groups had greater somatic symptoms and anhedonia. In keeping with this, anhedonia was the strongest predictor of disability. Absenteeism was also high across both studies.

Conclusions:

Unemployment and disability rates in MDD are high. The presence of anhedonia and medical comorbidity significantly influenced work status, emphasizing the need for treatment strategies to alleviate the additional symptom burden in this subpopulation.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, depression, workplace, unemployment, disability, absenteeism, Canada, prevalence

Abstract

Objectif :

Le trouble dépressif majeur (TDM) est une cause principale d’incapacité. L’incapacité de fonctionner au travail ajoute considérablement au fardeau des symptômes et accroît l’impact économique de ce trouble. Notre étude visait à rechercher les facteurs du TDM associés aux états de service dans les soins de première et troisième ligne.

Méthode :

Nous avons utilisé les données de 2 grandes bases de données pour notre analyse—Étude 1 : la base de données InSight, une revue des dossiers de patients du TDM traités par des médecins de soins de première ligne au Canada (n = 986); et Étude 2 : le projet collaboratif international sur les troubles de l’humeur, une étude transversale des patients des troubles de l’humeur (données canadiennes seulement : n = 274).

Résultats :

Les 2 études ont démontré des taux élevés de chômage et d’incapacité (de 30,3 % à 42,1 %). Le Québec affichait le taux de chômage le plus élevé (21 %) et la Colombie-Britannique comptait le pourcentage le plus élevé de patients en incapacité (15 %). Les groupes d’employés et de chômeurs étaient semblables selon les caractéristiques cliniques, toutefois, les personnes sans emploi pourraient être plus âgées, avoir une prévalence de comorbidité médicale, et être plus susceptibles de recevoir une benzodiazépine. Les taux accrus d’incapacité étaient associés à des antécédents d’abus dans l’enfance, à la durée de l’épisode dépressif majeur actuel, à la comorbidité, à l’usage de benzodiazépines, ainsi qu’à une plus grande gravité de la dépression et de l’anxiété. Les groupes de chômeurs en incapacité avaient des symptômes somatiques plus forts et plus d’anhédonie, laquelle était le prédicteur le plus fort de l’incapacité. L’absentéisme était aussi élevé dans les 2 études.

Conclusions :

Les taux de chômage et d’incapacité sont élevés dans le TDM. La présence d’anhédonie et de comorbidité médicale influençait significativement la capacité de travail, soulignant le besoin de stratégies de traitement pour alléger le fardeau additionnel des symptômes dans cette sous-population.

Major depressive disorder is one of the leading causes of disease burden in established market economies such as Canada.1,2 Some estimates indicate 8% of the workforce has a diagnosis of MDD.3 Specifically, MDD is responsible for the highest number of days out of role among physical or mental disorders.4

The economic impact of MDD has been documented at both organizational and individual levels.3,5–8 In 2001, Stephens and Joubert8 estimated that the annual cost of depression-related absenteeism in Canada was Can $4.5 billion, while Greenberg et al9 estimated this cost to be US$83.1 billion in the United States. Since then, health economic evaluation studies have indicated that mood disorders and their comorbidities are the most costly conditions to employers.10 According to Birnbaum et al,11 most of the cost associated with MDD stems from a reduction in job productivity and absenteeism. Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey also demonstrate the influence of MDD on personal earnings: the annual income of adults (18 years or older) with MDD was about 10% less than adults with no lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder.12 Further, in a Canadian sample, the prevalence of short-term disability due to depression was 2.5% in a sample of 63 000 employees, which translated into an estimated Can$20.1 million in lost productivity.13

Even though a substantial proportion of the affected population is at an employable age, little is still known about the prevalence and impact of MDD on the workforce.14 The National Comorbidity Survey—Replication, an epidemiologic study assessing prevalence rates of mental health disorders in the general population, showed that MDD results in 27.2 annualized lost workdays.15 Data from this study also indicated that functional impairment was significantly higher among people with mental disorders, compared with chronic medical conditions. This is further supported by 6-month data from the Health and Work Study sample, in which 229 employees with MDD and (or) dysthymia were compared with healthy control subjects and employees with arthritis. People with depression were 5 times more likely to be unemployed than those in the arthritic group.16 Depression-related disability also lasted longer and was more likely to recur.13 While 75% of employees returned to work following short-term disability, it is unclear whether depression was resolved at this time, which could suggest high levels of presenteeism in this group.

Clinical Implications

High prevalence of unemployment, disability, and absenteeism among depressed people in Canada is associated with more chronic and severe illness.

Anhedonia is a key clinical factor that distinguished employed from unemployed and disability groups, which is a symptom also linked to TRD.

Limitations

Lack of random sample may result in a nonrepresentative sample.

In primary care, clinical diagnoses were not confirmed by a structured interview, which may be particularly relevant in relation to Axis II disorders.

In contrast to studies examining mental health in the workforce,17 there has been less focus on work status in depressed groups.18 The goal of our study is to evaluate and compare work status and absenteeism as well as the associated clinical factors in 2 independent samples of patients with MDD within primary and tertiary care settings in Canada.

Methods

Study 1: Depression and Employment Status in Primary Care Sample

Study methods have been published for this data set.19 Briefly, this was a multi-site retrospective chart review where primary care physicians who had enrolled in prior registries in Canada were invited to participate. Physicians from 135 sites completed case report forms on consecutive patients aged 18 to 75 who met criteria for MDD. Axes I, II, and III diagnoses were based on physician assessment.

Demographic data collected were body mass index, vital signs, medication history, and side effects associated with current medication regimen. Clinical variables included in this analysis were duration of the current MDE, and presence of comorbidities (axes I, II, and II).

Socioeconomic variables collected were sex, age, ethnicity, province, and employment status. For working status, the options were as follows: in school, homemaker, unemployed more than 3 months, unemployed less than 3 months, on disability benefits, and employed. Only people in the unemployed and employed groups were included in the analysis. For people who were employed, a further descriptor was included to ascertain how much work, if any, was missed: none, a few hours in a day, and a few days in a month.

Study 2: Depression and Employment Status in a Tertiary Care Sample

The methodology has been previously published.20 Briefly, patients referred for consultation to the MDPU at the University Health Network, Toronto, were enrolled into a naturalistic cross-sectional study following written informed consent. Assessments included full demographic and medication information, the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview—Plus,21 the HRSD-17,22 the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,23 the TAQ,24 the QLESQ,25 the SDS,26 and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale.27 For a full listing of assessments see McIntyre et al.20 The purpose of the database was to determine demographic, diagnostic, and clinical differences among patients. To make comparisons between primary and tertiary care on a provincial and national level, only patients with MDD who identified as employed, unemployed, or disabled were entered into this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, differences across patients were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test or Student t test. Categorical variables were tested using the Pearson chi-square test or the Fisher exact test if the cell counts were less than 5. Logistic regressions were performed, and odds ratios, with its 95% confidence interval, were reported. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) or SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and tested using 2-sided tests at a significance level of 5%. A Boferroni correction for multiple comparisons was performed where appropriate.

Results

Study 1: Primary Care

A total of 1282 patient charts were reviewed, of which 1224 had work status identified. For the evaluation of factors associated with unemployment, disability, and employed groups, homemakers and students were excluded (n = 238), resulting in a sample of 986 patient charts for this portion of the analysis.

Differences Across Provinces in Employment Status

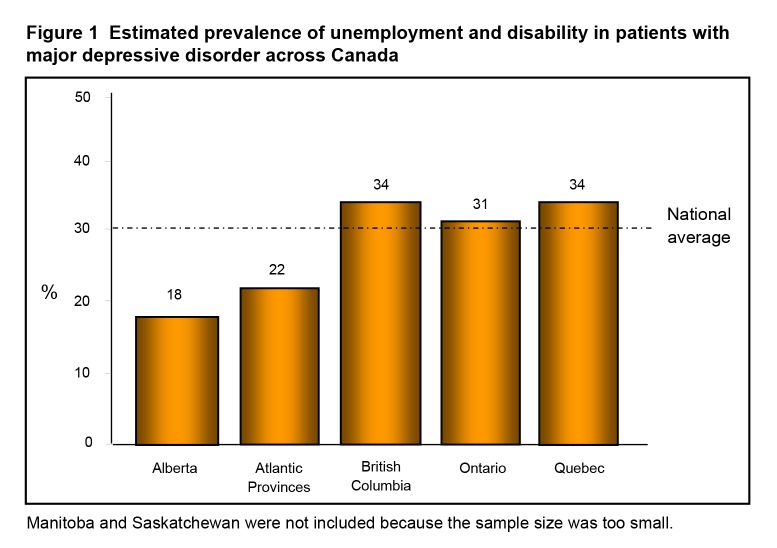

The unemployment–disability rate across Canada in this depressed group (n = 1224) was 30.3%, while the unemployment rate alone was 18.3%. About 50% of the sample was employed (Table 1). Figure 1 presents the unemployment–disability rates across provinces, which are based on estimations through primary care and may not reflect province-wide values. Quebec had the highest rate of unemployment (21.1%), followed by British Columbia (19.3%), Ontario (17.7%), the Atlantic provinces (15.0%), and Alberta (13.2%). British Columbia had the greatest percentage of patients on disability (14.9%), followed by Ontario and Quebec (both 13.3%). Employment rates ranged from 45.2% to 68.1% across provinces, with Quebec having the lowest rate and Alberta having the highest.

Table 1.

Patient demographics for primary care sample, Study 1

| Variable | Employed n = 615 | Unemployed n = 224 | On disability n = 147 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 44.4 (11.1) | 52.2 (16.0) | 48.5 (10.2) | <0.001 |

| Sex, female, % | 64.6 | 56.1 | 64.6 | ns |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian, % | 90.7 | 92.3 | 87.5 | ns |

| Current episode duration, months (IQR) | 12 (6 to 37) | 12 (6 to 30) | 23 (8 to 60) | 0.008 |

| Treatment resistance, %a | 18.9 | 22.2 | 32.4 | 0.003 |

| Axis I comorbidity, % | 55.3 | 59.3 | 65.9 | ns |

| Axis II comorbidity, % | 33.1 | 35.7 | 47.6 | 0.005 |

| Axis III comorbidity, % | 52.2 | 76.3 | 78.9 | <0.001 |

Defined as failure of at least 2 adequate antidepressant treatment trials

IQR = interquartile range; ns = nonsignificant

Figure 1.

Estimated prevalence of unemployment and disability in patients with major depressive disorder across Canada

Manitoba and Saskatchewan were not included because the sample size was too small.

Unemployment and (or) Disability Factors

Factors associated with increased unemployment or disability rates are reflected in Table 1. Sex, ethnicity, or presence of a comorbid Axis I disorder were not related to employment status.

Employed, Compared With Unemployed

There were few observed differences between the employed and unemployed groups, with the exception of greater likelihood of being female (P = 0.02) and higher age in the unemployment group (P < 0.001), as well as greater likelihood of having an Axis III comorbidity (P < 0.001), particularly cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, arthritis, and chronic pain. In addition, the unemployed group was more likely to be currently using a benzodiazepine (14.3% and 6.5%, respectively, P < 0.001) when compared with the employed group.

Employed, Compared With on Disability

Patients on disability had a higher age, along with a longer duration of current MDE (23 months, compared with 12 months, respectively, P = 0.02), greater likelihood of TRD (32.4% and 18.9%, respectively, P < 0.001), as well as higher axes I and II comorbidity (P = 0.02 and P = 0.001, respectively). Similarly to the employed, compared with the unemployed group, the disability group had greater Axis III comorbidity (P < 0.001), particularly arthritis, chronic pain, and type II diabetes mellitus. The disability group was also more likely to be taking a benzodiazepine (6.5% and 14.3%, respectively, P = 0.002) when compared with the employed group.

Absenteeism

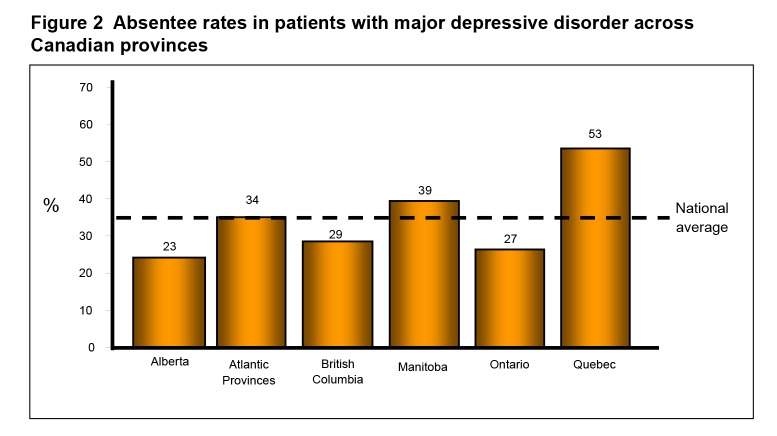

Absenteeism was significantly higher in Quebec (53%), compared with the rest of the provinces, and lowest in Alberta (23%, P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Among those employed, 34.2% reported some absenteeism due to depression. Among these patients, 92.6% missed at least 3 days of work in the preceding month, while 7.4% missed only a few hours in a day. Owing to the low report of missing a few hours in a day, this variable was collapsed with missing a few days a month for subsequent analyses. Ethnicity, age, and sex were not factors associated with absenteeism, while comorbidity was a factor. Axis I comorbidity was associated with a 15% increase in absenteeism (P < 0.001), while patients with an Axis II disorder reported absenteeism 10% more often than those without comorbidity (P < 0.001). Axis III comorbidity was also associated with a 9.2% increase in absenteeism (P = 0.02), particularly for chronic pain and insomnia (online eFigure 3). Interestingly, a shorter MDE duration was associated with greater absenteeism, compared with a longer duration MDE (8 months and 20 months, respectively, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Absentee rates in patients with major depressive disorder across Canadian provinces

Study 2: Tertiary Centre

The final sample size was 274 patients. Among the 1861 patients included in the database, 328 were MDD outpatients seen at the MDPU clinic. A further 54 patients were excluded owing to unreported employment status. The unemployment–disability rate in this group of patients with MDD was 41.4%, while the unemployment rate was 15.5%.

Unemployment and (or) Disability Factors

The demographic and key clinical variables for the employed, unemployed, and disability groups are presented in Table 2. Based on the one-way ANOVA, there are differences across groups in age, age when first treated for depression, number of lifetime suicide attempts and hospitalizations, as well as depression and (or) anxiety severity and functioning. These effects were primarily driven by differences between the employed and disability groups.

Table 2.

Patient demographics for tertiary care sample, Study 2

| Variable | Employed n = 138 | Unemployed n = 51 | Disability n = 85 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.2 (11.3) | 39.1 (11.2) | 46.9 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex, female, % | 56.5 | 60.8 | 69.4 | ns |

| Average education level achieved | Undergraduate degree | Undergraduate degree | College diploma | ns |

| Marital status, married, % | 47.8 | 29.4 | 44.7 | ns |

| Family psychiatric history, yes, % | 80.5 | 86.2 | 74.5 | ns |

| Age of symptom onset, years, mean (SD) | 22.1 (12.0) | 21.0 (11.0) | 25.4 (12.6) | ns |

| Age first treated, years, mean (SD) | 26.4 (11.5) | 24.1 (10.3) | 31.9 (9.7) | 0.01 |

| Number of MDEs, n (SD) | 13.2 (28.7) | 6.0 (5.6) | 11.5 (17.5) | ns |

| Number of suicide attempts, n (SD) | 0.16 (0.4) | 0.49 (1.3) | 0.56 (1.5) | 0.02 |

| Number of hospitalizations, n (SD) | 0.12 (0.4) | 0.33 (1.0) | 0.97 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| HRSD-17 total score, mean (SD) | 13.0 (7.5) | 14.6 (8.2) | 21.2 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| MADRS total score, mean (SD) | 18.5 (10.8) | 19.6 (9.7) | 28.4 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| TAQ total score, mean (SD) | 119.9 (48.3) | 141.8 (48.3) | 157.6 (50.5) | <0.001 |

| QLESQ total of maximum score, % (SD) | 48.7 (15.3) | 38.2 (15.3) | 34.6 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| SDS total score, mean (SD) | 14.5 (8.0) | 18.8 (7.8) | 22.9 (6.6) | <0.001 |

| EWPS total score, mean (SD) | 40.2 (23.8) | 83.7 (26.1) | 92.5 (21.5) | <0.001 |

EWPS = Endicott Work Productivity Scale; HRSD-17 = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression—17 item; MADRS = Montgomery Åsberg Rating Scale for Depression; MDE = major depressive episode; ns = nonsignificant; QLESQ = Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; TAQ = Trimodal Anxiety Questionnaire

Employed and Unemployed

Interestingly, the employed and unemployed groups had similar demographic profiles (age at onset, hospitalizations, medical or psychiatric comorbidity, and family history), as well as clinical variables (depression severity, anxiety severity, and physical and [or] sexual abuse history). The only significant between-group difference was in functioning: the unemployed group demonstrated poorer overall function (QLESQ: 38.2 and 48.7, respectively, P = 0.001) and a trend toward less social functioning in the unemployed group (SD: 5.0 and 6.6, respectively, P = 0.005, did not meet multiple correction). A trend toward greater levels of anxiety was also demonstrated in the unemployed group (TAQ: 141.8 and 119.9, respectively, P = 0.006, did not meet multiple correction). Lastly, the unemployed group was more likely to be taking a current benzodiazepine than the employed group (27.5% and 13.0%, respectively, P = 0.02).

Employed and on Disability

The employed group was younger, had fewer hospitalizations, and a trend toward younger age when first treated (Table 2). This group also had decreased likelihood of childhood physical or sexual abuse (17.6% and 29.1%, respectively, P = 0.05). The disabled group had greater prevalence of axes I and III comorbidities: Axis I—panic disorder with agoraphobia (21.5% and 7.6%, respectively, P = 0.003), social phobia (37.8% and 22.8%, respectively, P = 0.02), and posttraumatic stress disorder (16.5% and 3.0%, respectively, P < 0.001); Axis III—endocrine and (or) metabolic disorders (82.0% and 63.4%, respectively, P = 0.01), rheumatological and (or) autoimmune (50.0% and 16.5%, respectively, P < 0.0001), neurologic (77.3% and 61.6%, respectively, P = 0.04), gastrointestinal (53.1% and 36.6%, respectively, P = 0.04), and hematologic (36.0% and 18.4%, respectively, P = 0.03).

The disabled group also had significantly greater depression severity (HDRS-17 score 21.2 and 13.0, respectively, P < 0.001). The items that most contributed to this difference were reduced mood, interest, energy, and libido, and psychomotor retardation, which were also significantly different between the unemployed and disabled groups (Table 3). Sleep, suicide, guilt, and psychic anxiety symptoms were significantly more severe in people on disability, compared with those employed. In addition to depression severity, the disability group demonstrated greater levels of anxiety (TAQ: 157.6 and 119.9, respectively, P < 0.001), an effect mostly driven by somatic and behavioural subscales. Functioning was also greatly reduced in the disability group (SD total: 22.9 and 14.5, respectively, P < 0.001); a difference that was equally weighted across work, social, and family life and (or) home responsibilities. Similar to the unemployed group, the disability group was more likely to be on a current benzodiazepine than the employed group (41.2% and 13.0%, respectively, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Differences in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression—17 items across groupsa

| Employed, compared with unemployed | Unemployed, compared with disability (all higher in disability) | Employed, compared with disability (all higher in disability) |

|---|---|---|

| No items met significance | Interest and work | Interest and work |

| Mood | Mood | |

| Psychomotor retardation | Psychomotor retardation | |

| Energy | Energy | |

| Libido | Libido | |

| Hypochondriasis | Psychic anxiety | |

| Insomnia middle and late | ||

| Guilt | ||

| Suicide |

Only items meeting Bonferroni correction (P < 0.003) are presented.

Unemployment and (or) Disability Prediction

Binary logistic regression modelling did not reveal a strong predictor of unemployment, despite the presence of variables that were significant between groups. However, in the employed and disability prediction model, loss of interest predicted 27.6% of the variance and accurately predicted 78.6% of employed patients and 77.0% of patients on disability (P < 0.001). The addition of current benzodiazepine use improved the prediction to 73.8% and 90.0%, respectively (P < 0.001).

Absenteeism

In the preceding week, 49.5% of the patients reported at least 1 hour of absenteeism, with the average being 7.1 (SD 14.5) hours. Among these patients, 14.1% reported missing at least 1 day, while 22.1% missed 3 or more days. Sex, age, marital status, family history of mental illness, history of childhood maltreatment, and depression or anxiety severity were not associated with absenteeism. Axes I and III comorbidities also did not affect absenteeism. Logistic regression did not provide a model to predict absenteeism.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated high rates of unemployment and disability among patients with MDD, in both primary and tertiary care groups of depressed patients. Overall, the employed and unemployed groups were similar, based on clinical characteristics. Further, impairment was significantly different across provinces in the primary care sample. In contrast to unemployment, disability was associated with greater clinical complexity and severity. Additionally, we also report high levels of absenteeism that differed significantly across provinces and was associated with a shorter MDE duration and comorbidity. To our knowledge, few studies have assessed the impact of the clinical profile of patients with MDD on employment status.

The high level of unemployment and disability observed in this sample is consistent with previous reports on depressed patients and employment.2,13,15,16 Unemployment rates of 30% to 40% among depressed patients in primary care and in a tertiary care centre are in sharp contrast to Canadian census data. In 2006, the national unemployment rate was 6.3%,28 compared with the 15.5% to 17.1% observed in our study. Broken down by province, it is clear that the level of unemployment is, in some cases, doubled or tripled in depressive populations, compared with province-wide data: Quebec (21.1%, compared with 8.0%), British Columbia (19.3%, compared with 4.8%), Ontario (17.7%, compared with 6.3%), Atlantic provinces (15.0%, compared with 9.4%), and Alberta (13.2%, compared with 3.4%).

Surprisingly, there were few demographic or clinical differences between employed and unemployed patients with MDD, although those in the primary care sample were older and had greater Axis III comorbidity, and this was not observed in the tertiary care sample; unemployment was related to benzodiazepine use in both samples. This could be potentially related to the various reasons for unemployment, which do not always reflect poor work performance (for example, laid off and quit due to job dissatisfaction). In our study, we did not evaluate reasons for unemployment to this extent, thus conclusions about the clinical correlates of being unemployed solely owing to depression cannot be drawn. In contrast, disability reflects an inability to perform based on medical or psychiatric reasons. As a result, an unemployed group in an MDD sample is likely to be more heterogeneous regarding symptoms and demographic background than a disability group, diluting any potential effects of depression on unemployment or vice versa. This is highlighted by the finding that disability was associated with higher age, axes I and III comorbidity, and benzodiazepine use across both studies. In the primary care group, disability was also associated with increased MDE duration, greater prevalence of Axis II comorbidity, and TRD, while in the tertiary care sample there were additional associations with higher depression severity, anxiety, hospitalizations, poorer functioning, and history of childhood physical and (or) sexual abuse. Overall, our study suggests that, compared with employed and unemployed patients, those on disability reflect people who are more chronically ill.

Several lines of research have consistently demonstrated the ability of depression severity to predict employment status, presenteeism, and absenteeism,29 but, to our knowledge, few have evaluated contributing symptom clusters. Assessment of differences in depressive symptom clusters among employed, unemployed, and disability groups in MDD can help determine whether there are depression subtypes that are disproportionately impaired in the workplace, and can also provide an indication of what interventions could be most beneficial. Unemployed patients are more likely to be anhedonic, with low energy and higher levels of anxiety. This points to a lack of desire and motivation as a primary limitation to gainful employment, compared with other somatic or cognitive symptoms. Patients with disability have the same symptom clusters, with greater impairment in these areas as well as additional somatic (sleep) and cognitive symptoms (guilt, suicide). Based on these findings, it is not unexpected that TRD was found to be higher in the unemployed group, and higher still in the disability group, as these symptoms map onto the patient profile seen in this group.19 The prediction of disability via loss of interest is also consistent with the TRD literature, where anhedonia has been found to be a predictor of antidepressant nonresponse.30,31

The higher rate of benzodiazepine use in unemployed and disability groups could be explained by the increased comorbidity of anxiety disorders, particularly in the disability group. Benzodiazepines can also affect cognition, which is, in itself, impacted in depression,32–35 thereby affecting work status.36 Given dysfunction in working memory, attention, and psychomotor speed have been reported with benzodiazepine use,37,38 it is not surprising that the prevalence of receiving a benzodiazepine in the unemployed and disability groups was higher than the employed group, and moreover, that it predicted disability status. Further, the adverse effect of cognition on functional outcomes can also be moderated by the presence of comorbidities, particularly those that have an inflammatory component (for example, rheumatoid arthritis and obesity).39–41 This is consistent with the greater prevalence of endocrine and (or) metabolic disorders and arthritis, particularly among patients on disability.

Higher odds of absenteeism among MDD patients have frequently been reported.15,16,42 Trials typically demonstrate an average of 1 workday per month.28 The high level of absenteeism in our study (92% with at least a few days/month in primary care and 22.1% at least 1 day/week in tertiary care) reflect the difference between a clinical sample and a community sample. Second, the discrepancy between the 2 clinical samples may relate to the different time frames queried (month, compared with week) as well as to grouping all absences together irrespective of the reason in the primary care group, while in the tertiary care sample only absences due to depression were included in the analysis. We also demonstrated absenteeism was associated with greater comorbidity (Study 1: axes I to III), which is a significant issue related to work impairment.43 The tertiary care patients had similarly high rates of comorbidity across employed, unemployed, and disability groups, suggesting a higher degree of clinical complexity in this sample. Finally, we reported absenteeism was related to shorter MDE duration. This could be related to 2 issues: people with a longer duration transition to disability status, and people with a shorter duration may have more availability of sick days than those who have been depressed for longer.

The primary limitation of this analysis is the lack of an a priori design to measure the effects of depression on employment status. Second, these results may not be generalizable to other clinical populations owing to a lack of random sampling and, therefore, may not reflect a representative sample. Further, diagnoses in primary care were based on physician report and did not follow a structured interview, which limits conclusions about increased comorbidity in unemployed and disability groups within this sample, particularly concerning Axis II disorders. Additionally, a work assessment scale to further characterize details of impairment in work function was not used nor were economic data, precluding an estimation of loss of work productivity.

In summary, rates of unemployment and (or) disability in MDD are high and vary across Canadian provinces. The impact of MDE duration, comorbidity, as well as anhedonia on work status emphasizes the need for early intervention as well as the development of effective workplace strategies to combat impairment in performance and transition to disability.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the Canadian Heart Research Centre (www.chrc.net) and Biovail.

Dr Rizvi has received travel funding from Eli Lilly and St Jude Medical. Anna Cyriac and Laura Ashley Gallagher have no conflicts to report. Etienne Grima, Mary Tan, and Dr Lin are employees of the Canadian Heart Research Centre. Dr Lin has received speaking honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Dr McIntyre is on speaker and advisory boards for, or has received research funds from, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Ortho, Organon, Lundbeck, Pfizer, the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Institutes of Mental Health, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Shire, and Merck. Dr Kennedy has received grant and research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Clera Inc, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Ortho, Lundbeck, Ontario Brain Institute, Servier, and St Jude Medical. He is a consultant to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Servier, and St Jude Medical.

Abbreviations

- HRSD

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- MDE

major depressive episode

- MDPU

Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit

- QLESQ

Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

- TAQ

Trimodal Anxiety Questionnaire

- TRD

treatment-resistant depression

- SDS

Sheehan Disability Scale

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9063):1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patten SB, Kennedy SH, Lam RW, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. I. Classification, burden and principles of management. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S5–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewa CS, Lesage A, Goering P, et al. Nature and prevalence of mental illness in the workplace. Healthc Pap. 2004;5(2):12–25. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..16820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munce SE, Stansfeld SA, Blackmore ER, et al. The role of depression and chronic pain conditions in absenteeism: results from a national epidemiologic survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(11):1206–1211. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318157f0ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. The health and productivity cost burden of the “top 10” physical and mental health conditions affecting six large US employers in 1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al. Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18(5):163–171. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephens T, Joubert N. The economic burden of mental health problems in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2001;22(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewa CS, Chau N, Dermer S. Examining the comparative incidence and costs of physical and mental health-related disabilities in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(7):758–762. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181e8cfb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D, et al. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(1):78–89. doi: 10.1002/da.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntyre RS, Wilkins K, Gilmour H, et al. The effect of bipolar I disorder and major depressive disorder on workforce function. Chronic Dis Can. 2008;28(3):84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dewa CS, Goering P, Lin E, et al. Depression-related short-term disability in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(7):628–633. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackmore ER, Stansfeld SA, Weller I, et al. Major depressive episodes and work stress: results from a national population survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):2088–2093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.104406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of US workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1561–1568. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, et al. Unemployment, job retention, and productivity loss among employees with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(12):1371–1378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dooley D, Fielding J, Levi L. Health and unemployment. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:449–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jefferis BJ, Nazareth I, Marston L, et al. Associations between unemployment and major depressive disorder: evidence from an international, prospective study (the predict cohort) Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(11):1627–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizvi SJ, Grima E, Tan M, et al. Treatment-resistant depression in primary care across Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(7):349–357. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntyre RS, Kennedy SH, Soczynska JK, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder: results from the international mood disorders collaborative project. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(3) doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00861gry. pii: PCC.09m00861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehrer PM, Woolfolk RL. Self-report assessment of anxiety: somatic, cognitive, and behavioral modalities. J Behav Assess. 1982;4:167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, et al. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endicott J, Nee J. Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS): a new measure to assess treatment effects. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akyeampong EB. Canada’s unemployment mosaic, 2000 to 2006. Perspectives on Labour and Income. 2007;8:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerner D, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):401–410. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31816bae50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMakin DL, Olino TM, Porta G, et al. Anhedonia predicts poorer recovery among youth with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment-resistant depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(4):404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uher R, Perlis RH, Henigsberg N, et al. Depression symptom dimensions as predictors of antidepressant treatment outcome: replicable evidence for interest-activity symptoms. Psychol Med. 2012;42(5):967–980. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gualtieri CT, Morgan DW. The frequency of cognitive impairment in patients with anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder: an unaccounted source of variance in clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1122–1130. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reppermund S, Ising M, Lucae S, et al. Cognitive impairment in unipolar depression is persistent and non-specific: further evidence for the final common pathway disorder hypothesis. Psychol Med. 2009;39(4):603–614. doi: 10.1017/S003329170800411X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nebes RD, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, et al. Decreased working memory and processing speed mediate cognitive impairment in geriatric depression. Psychol Med. 2000;30(3):679–691. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brüne M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(2):141–168. doi: 10.1038/nrd3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Soczynska JK, et al. Cognitive deficits and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: determinants, substrates, and treatment interventions. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(6):515–527. doi: 10.1002/da.22063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dawson J, Boyle J, Stanley N, et al. Benzodiazepine-induced reduction in activity mirrors decrements in cognitive and psychomotor performance. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(7):605–613. doi: 10.1002/hup.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, et al. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639–658. doi: 10.1007/BF03262280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntyre RS, Liauw S, Taylor VH. Depression in the workforce: the intermediary effect of medical comorbidity. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(Suppl 1):S29–S36. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(11)70006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Jerrell JM, et al. Obesity and mental illness: implications for cognitive functioning. Adv Ther. 2013;30(6):577–588. doi: 10.1007/s12325-013-0040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallin K, Solomon A, Kåreholt I, et al. Midlife rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of cognitive impairment two decades later: a population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31(3):669–676. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rost K, Fortney J, Coyne J. The relationship of depression treatment quality indicators to employee absenteeism. Ment Health Serv Res. 2005;7(3):161–169. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-5784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.