Abstract

The invasion of circulating monocytes/macrophages (MΦ)s from the peripheral blood into the central nervous system (CNS) appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis of HIV dementia (HIV-D), the most severe form of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), often confirmed histologically as HIV encephalitis (HIVE). In order to determine if trafficking of monocytes/MΦs is exclusive to the CNS or if it also occurs in organs outside of the brain, we have focused our investigation on visceral tissues of patients with HIVE. Liver, lymph node, spleen, and kidney autopsy tissues from the same HIVE cases investigated in earlier studies were examined by immunohistochemistry for the presence of CD14, CD16, CD68, Ki-67, and HIV-1 p24 expression. Here, we report a statistically significant increase in accumulation of MΦs in kidney, spleen, and lymph node tissues in specimens from patients with HIVE. In liver, we did not observe a significant increase in parenchymal macrophage accumulation, although perivascular macrophage accumulation was consistently observed with nodular lesions in 4 of 5 HIVE cases. We also observed an absence of CD14 expression on splenic MΦs in HIVE cases, which may implicate the spleen as a potential source of increased plasma soluble CD14 in HIV infection. HIV-1 p24 expression was observed in liver, lymph node and spleen but not kidney. Interestingly, renal pathology suggestive of chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (possibly due to chronic pyelonephritis), including tubulointerstitial scarring, chronic interstitial inflammation and focal global glomerulosclerosis, without evidence of HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), was seen in four of eight HIVE cases. Focal segmental and global glomerulosclerosis with tubular dilatation and prominent interstitial inflammation, consistent with HIVAN, was observed in two of the eight cases. Abundant cells expressing monocyte/MΦ cell surface markers, CD14 and CD68, were also CD16+ and found surrounding dilated tubules and adjacent to areas of glomerulosclerosis. The finding of co-morbid HIVE and renal pathology characterized by prominent interstitial inflammation may suggest a common mechanism involving the invasion of activated monocytes/MΦs from circulation. Monocyte/MΦ invasion of visceral tissues may play an important role in the immune dysfunction as well as comorbidity in AIDS and may, therefore, provide a high value target for the design of therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: HIV, CNS, CD16, pyelonephritis, macrophage, HIVAN, co-morbidity

INTRODUCTION

Mononuclear phagocytes (MPs), which include monocytes and macrophages (MΦ)s, play a prominent role in the development of the most severe form of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), HIV-1 associated dementia (HIV-D), and one of the pathologies of HIV-D, HIV encephalitis (HIVE). Mechanisms leading to HIVE are not completely understood, however, central nervous system (CNS)-associated MΦs, including perivascular MΦs, and resident microglia are believed to play a prominent role in neuronal injury and dysfunction. Indeed, significant MΦ accumulation in the CNS is a better correlate of HIV-D than productive viral infection, [1] and the histological basis of HIV-D is believed to represent an active inflammatory process often resulting in neurocognitive impairment.

Previous studies have demonstrated an increase in the number of monocytes expressing CD16, a low affinity Fcγ receptor, in circulation of patients with HIV-D, as compared to patients with HIV/AIDS without dementia [2]. In a cross-sectional analysis, we found the frequency of circulating CD16+ monocytes correlates positively with viral load of HIV infected persons and inversely with CD4+ T-cell counts in subjects with CD4+ cell counts equal to or less than 450 cells/μl [3]. These findings suggest a possible role for CD16+ monocytes in the development and progression of HIV-D and AIDS. In support of this hypothesis, we previously reported that CD14+/CD16+ MPs accumulate in the CNS of patients with HIVE, as compared to the CNS of HIV+ patients without encephalitis and seronegative controls [4]. These cells comprise nodular lesions and perivascular cuffs and appear to be the primary reservoir of productive HIV infection in the CNS [4]. Further, the large number of CD16+ MPs in CNS, further defined as MΦs, observed in HIVE does not appear to be due to proliferation, suggesting increased trafficking of these cells from the periphery [5].

CD16+ monocytes are believed to represent an activated monocyte phenotype with some shared features of tissue MΦs, in which they are more phagocytic than monocytes lacking CD16 expression and express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [6]. In view of our findings in HIVE CNS, we previously suggested that CD16+ monocytes might also be more invasive, enabling them to cross the blood-brain barrier into the CNS [4]. We further considered the possibility that trafficking of CD16+ monocytes in HIV infection may not be exclusive to the CNS compartment, but may also enter visceral tissues. In the study presented here, we investigated monocyte/MΦ invasion by immunohistochemistry in liver, lymph node, spleen, and kidney autopsy tissue from patients with HIVE, using human monoclonal antibodies to CD14, CD16, and CD68, and compared the findings to the same tissues from HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis and seronegative controls. Tissues were further examined for local monocyte/MΦ proliferation, using an antibody against Ki-67, and productive HIV-1 infection, using an antibody against HIV-1 p24 gag.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human tissue samples

Paraffin-embedded liver, lymph node and spleen tissue sections acquired at autopsy from patients with HIVE were obtained from the Manhattan Brain Bank (MHBB; U24MH100931), member of the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium [7]. Age and sex-matched specimens from seronegative and HIV/AIDS adults without CNS disease were obtained from the Drexel University College of Medicine Autopsy Service. A total of eight HIVE cases, six HIV/AIDS cases without CNS disease and five seronegative controls were analyzed. Additionally, paraffin-embedded kidney tissue sections acquired at autopsy from eight patients with HIVE (Table 1) were obtained from MHBB and analyzed. Light microscopic haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) analyses were performed on all tissues by two independent reviewers (SC and TF). Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stained kidney tissues were analyzed by a single renal pathologist (VDD), focusing on glomerular, tubulointerstitial, and vascular pathology while discounting autolytic changes.

Table 1.

| PID | Age | Sex | Race | CD4 | VL | ART at death | Creatinine (mg/dL) | Proteinuria (mg/dL) | Renal Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10017 | 43 | M | White | 7 | 389,120 | No | 0.9 | 30 | Chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy/nephritis with severe tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, many hyaline casts and chronic interstitial inflammation. |

| 10026 | 37 | M | Hisp | 111 | 269,342 | No | 1.6 | Negative | Chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy/nephritis with wedge- shaped cortical scars, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and chronic interstitial inflammation. |

| 10070 | 37 | M | Black | 0 | >750,000 | No | 2.0 | 100 | Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, many hyaline casts, and diffuse chronic interstitial inflammation. |

| 509 | 46 | M | White | 203 | 80,000 | Yes | n/a | n/a | No specific pathology with occasional pigmented casts. |

| 519 | 50 | M | Hisp | 1 | 58,419 | No | 2.9 | Negative | Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with patchy tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and diffuse chronic interstitial inflammation. |

| 537 | 45 | F | Black | 6 | n/a | No | 5.4 | 300 | HIVAN with focal segmental and global glomerulosclerosis involving 15–20% of glomeruli, focal collapsing features and tubular microcysts and diffuse (90%) interstitial inflammation by mononuclear leukocytes. |

| 540 | 47 | M | Black | 1 | 683,333 | Yes | 3.3 | 100 | HIVAN with focal segmental and global glomerulosclerosis involving 20–25% of glomeruli, focal collapsing features and tubular microcysts and diffuse (60%) interstitial inflammation by mononuclear leukocytes |

| 603 | 49 | M | Black | 2 | 493,381 | No | 1 | n/a | No specific pathology with mild focal arteriosclerosis. |

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described [5] on 4μm tissue sections. Mouse monoclonal anti–human antibodies were used as follows: CD68 (Novocastra, clone KP1) was used at a 1:400 dilution; CD14 (Novocastra, clone 7) was used at a 1:50 dilution; CD16 (Novocastra, clone 2H7) was used at 1:40; Ki–67 (Novocastra, clone MM1) used at a 1:25 dilution and HIV–1 p24 (Dako, clone Kal–1) used at 1:5. Archival lymph node and intestine from HIV–1 seronegative individuals were used as positive controls for CD14, CD68, CD16 and Ki-67 detection. Archival lymph node from a patient with HIV/AIDS was used as a positive control for HIV-1 p24 detection. Negative controls included intestine and brain tissues incubated in blocking solution with IgG1 and IgG2 isotype control antibodies at concentrations equal to the highest IgG antibody concentration. Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated anti–mouse IgG, avidin–biotin complex and alkaline phosphatase–Vector Red (Vector Laboratories) or peroxidase–3, 3′–diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma) according to manufacturers’ instructions. A catalyzed signal amplification method was used (Catalyzed Signal Amplification System, Dako) for detection of Ki-67 and HIV-1 p24, as per the manufacturer’s instructions, with the following exceptions: Primary antibody was diluted in Antibody Diluent with Background Reducing Components (Dako) and allowed to incubate on tissues overnight at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched by incubating sections in 3% H2O2/methanol.

Quantitation of immunohistochemical specimens and statistical analysis

Quantification of CD16 and CD68 expression in lymph node, spleen, kidney, and liver was completed using a bioquantification software system (Bioquant Image Analysis Program). A total of ten 20X microscopic fields were assessed per tissue section using a microscope (Nikon) with a motorized x, y stage and a digital camera (Q-Imaging Retiga) that were linked to a computer with the software program. The areas of analysis were adjusted to accommodate the area of the tissues examined and are indicated on the associated graph. An unbiased quantification approach was used, with a random start, followed by the systematic sampling of 10 adjacent (non-overlapping) sites within the region of interest using the motorized stage option. Analysis conditions were retained for each antigen of interest by white-balancing the camera prior to data acquisition and maintaining the same light intensity of the microscope for each slide. The Videocount Area Array and color thresholding options of the Bioquant software were utilized for these measurements, as previously defined in detail [8]. Briefly, videocount (VC) area is defined as the number of pixels in a field that meet a user-defined color threshold of staining. The user-defined color threshold of immunostaining for each antigen (i.e., positivity of each antigen) was defined by setting the red-green-blue values to detect the range of positive signal values for a particular immunostained antigen, while excluding color ranges of other antigens and background noise. The threshold values for each antigen were stored in the computer program and maintained for each immunohistochemical analysis across all subjects and groupings. The percent positivity for each field and antigen was determined by dividing the number of positive pixels (those that matched the defined color threshold) by the total number of pixels within the VC area, and multiplying by 100. Data are expressed as the percentage of antigen positivity per field area. The assessment was carried out in a blinded fashion.

Statistical analyses

The percent expression per area of CD16 and CD68 in the tissues examined was evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test and one-tailed unpaired t test. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, version 6.0d). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Utilizing a series of immunohistochemical markers that identify specific MP subsets previously reported in the CNS of patients with HIVE [4,5], we investigated the possibility that these MPs are more invasive and, as such, may be present in visceral tissues, as well. Lymph node, spleen, kidney, and liver autopsy tissues from the same HIVE cases investigated in our previous studies were examined by immunohistochemistry for CD68, CD16, CD14, Ki-67 and HIV-1 p24 expression.

Accumulation of CD16+ MPs is not limited to brain in HIVE

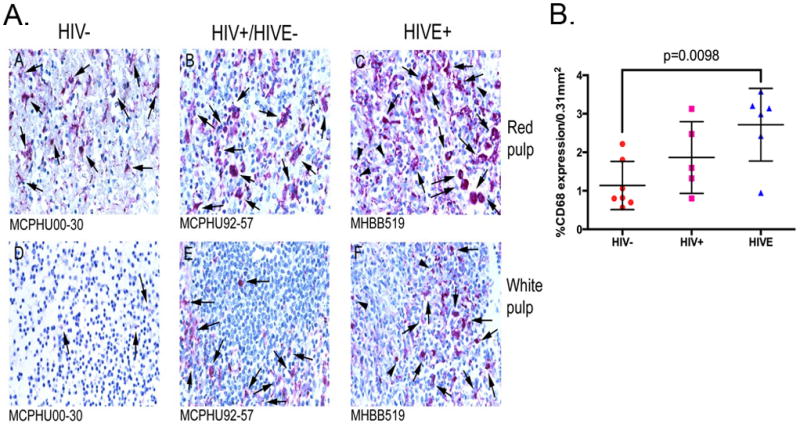

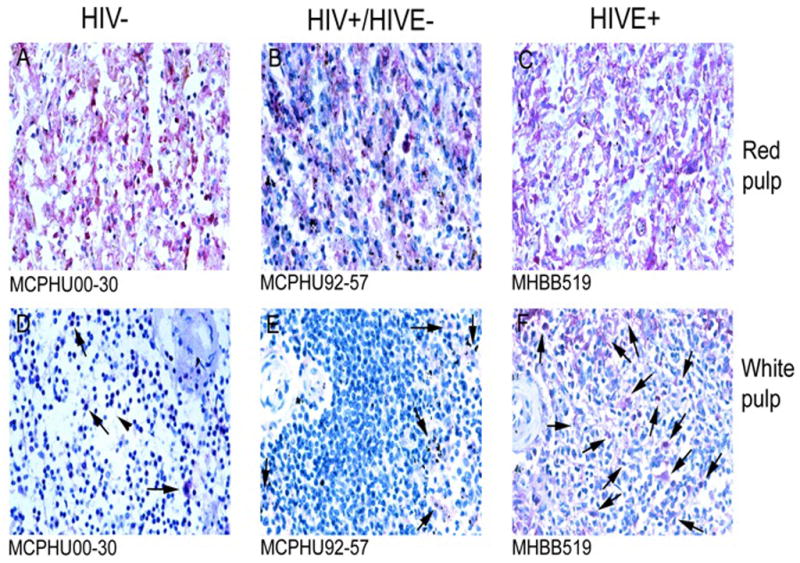

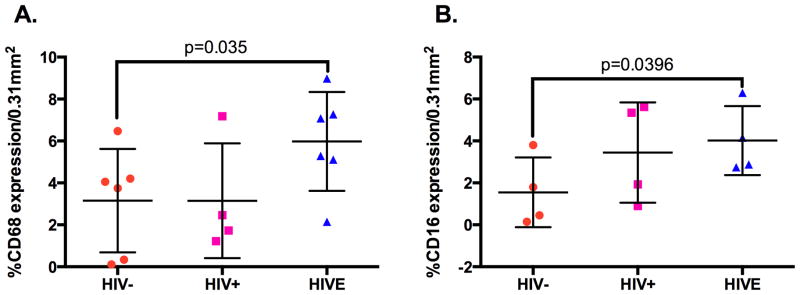

In spleen, CD68 (Figure 1A) and CD16 (Figure 2) demonstrate a similar pattern of expression, which are seen at a higher frequency in red pulp, as compared to white pulp. An increase in the number of both CD68+ and CD16+ cells in HIVE cases was observed, relative to seronegative controls (Figures 1A and 2). Quantitation of CD68+ cells showed this difference to be statistically significant between these two groups (Figure 1B). Additionally, the intensity of CD68 expression appears to be greater in HIVE than in the two comparative groups (Figure 1A). Both CD68 and CD16 positive cells appear primarily in the highly vascularized red pulp in spleen from HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis and seronegative controls, with an increase in the frequency of these cells seen in HIVE, relative to seronegative controls (Figures 1A and 2, Panels A and C), with intermediate frequency of cells in HIV/AIDS without encephalitis (Figures 1A and 2, Panel B). Furthermore, in addition to red pulp, HIVE spleen also showed significant accumulation of CD68+ and CD16+ MPs in white pulp, which generally consists of lymphoid aggregations (Figures 1A and 2, Panels D, E and F).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

CD14 expression differed largely between that observed in HIVE spleen versus that seen in the two comparative groups (data not shown). CD14+ cells are observed, predominantly, in the red pulp of seronegative individuals, with lesser expression seen in HIV/AIDS without encephalitis. Interestingly, CD14 expression is not observed in cells in HIVE spleen. Possible explanations for this finding are discussed in the Conclusions.

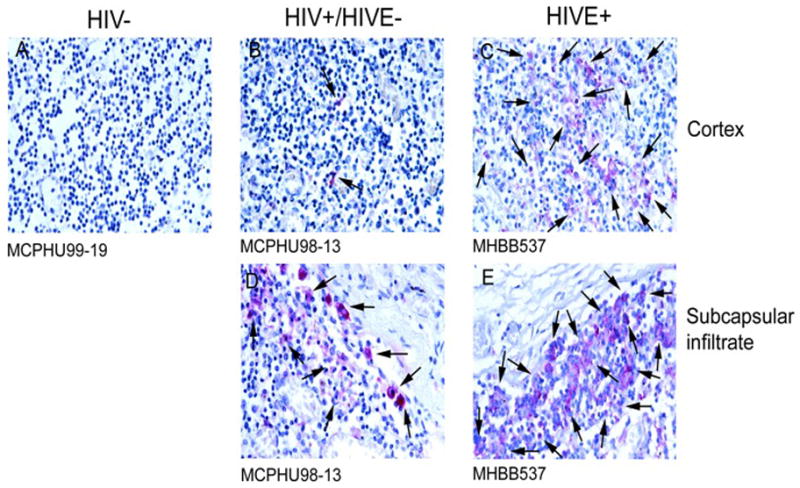

Similar to results observed in spleen, examination of lymph node showed an increase in CD16+ cells in HIVE, as compared to seronegative controls, with intermediate frequency in HIV/AIDS without encephalitis (Figure 3, Panels A, B, and C). Similar findings were also seen with CD68 expression (data not shown). Quantitation of CD16 and CD68 positive cells in immunohistochemical specimens from all cases investigated showed a statistically significant increase in the number of CD16+ and CD68+ cells in lymph node from HIVE, relative to seronegative controls and as determined by a one-tailed T test (Figure 4). As our major question is whether there is an increase in the number of CD16 and/or CD68 positive cells in HIVE, one-tailed test was considered appropriate. Results did not reach significance using an ordinary ANOVA. In HIV/AIDS without encephalitis, CD16+ cells were seen predominantly within the lymph node marginal zones, outside of the germinal centers (Figure 3, Panel B). In contrast, HIVE lymph node demonstrated no delineation between these two areas, where CD16+ cells were seen well into the germinal centers (Figure 3, Panel C). Further, subcapsular infiltrate, which is composed primarily of MPs, demonstrated significant CD16 expression in HIVE, as compared to HIV/AIDS without encephalitis (Figure 3, Panels D and E). These results are consistent with the increased frequency of circulating CD16+ monocytes reported in HIV/AIDS without dementia, with an even greater frequency seen in those with dementia [2]. The autopsy lymph node tissues from seronegative individuals analyzed in this study did not include the subcapsular region, thus the level of CD16 expression in this region could not be compared between the HIV/AIDS without encephalitis and seronegative groupings. Distinction among the three groups was also made by CD14 expression (data not shown), where CD14 was not observed in seronegative controls but moderate expression was seen in HIV/AIDS without encephalitis, which was greater in HIVE.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

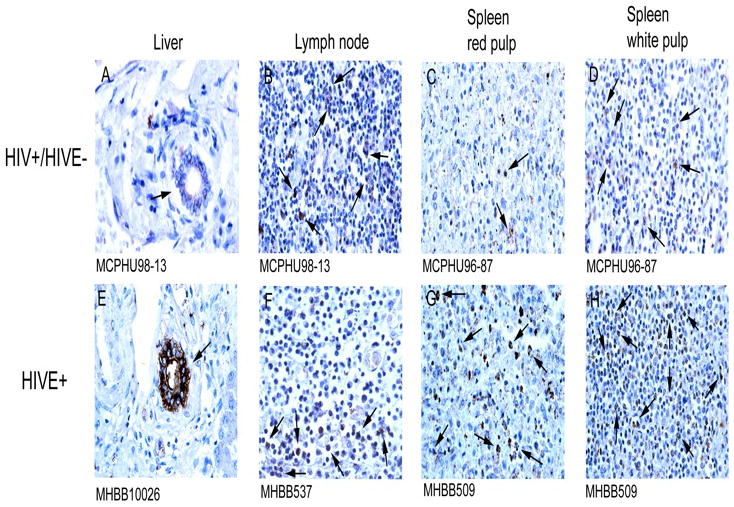

In liver of patients with HIVE, marked accumulation of CD16+ cells around blood vessels, similar to “perivascular cuffing” in the CNS that is a hallmark of HIVE, is seen (Figure 5, Panels F and G). Similar observations were made with CD14 and CD68 immunohistochemistry (data not shown). Quantification did not reveal a significant increase in the number of parenchymal CD16+ MPs in HIVE liver, which may reflect the small number of cases studied, and the apparent variability of macrophage accumulation among the four seronegative cases analyzed (data not shown). We did observe, however, consistent observation of perivascular macrophage accumulation in HIVE liver, with nodular lesions observed in 4 of 5 cases studied. The majority of stained cells within the liver parenchyma appear to be Kupffer cells and seem to show upregulation of CD16 (brighter) in HIVE, as compared to the seronegative and HIV/AIDS without encephalitis groupings (Figure 5, compare panels A, B, and C).

Figure 5.

Greater HIV-1 p24 antigen is seen in liver, lymph node and spleen in HIVE than HIV/AIDS without encephalitis, however to varying degrees in the different tissues examined (Figure 6). Interestingly, HIV-1 p24 expression, suggestive of a productive infection, is not observed in CD16+ MPs found in the liver, but rather in the epithelium of a limited number of bile ducts (Figure 6, Panels A and E). In contrast, lymph node and spleen appeared to demonstrate productive HIV infection, presumably, in immune cells (Figure 6, Panels B–D and Panels F–H). With the exception of lymph nodes, which are involuted in HIVE, overall greater HIV-1 p24 immunopositivity is seen in tissue from patients with HIVE, as compared to those with HIV/AIDS but without encephalitis (Figure 6, compare Panels A–D to Panels E–H).

Figure 6.

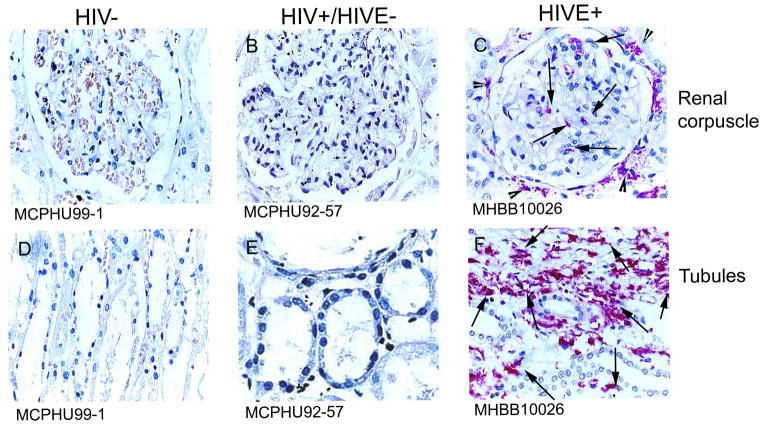

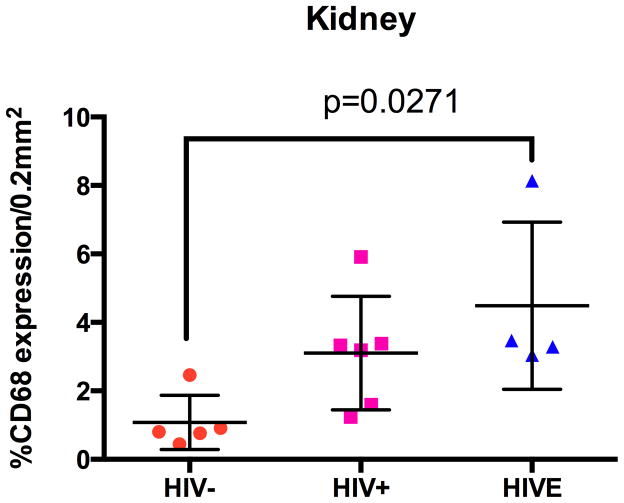

Accumulating monocytes/MΦs in kidney of patients with HIVE exhibit similar phenotypic markers as those that accumulate in the CNS

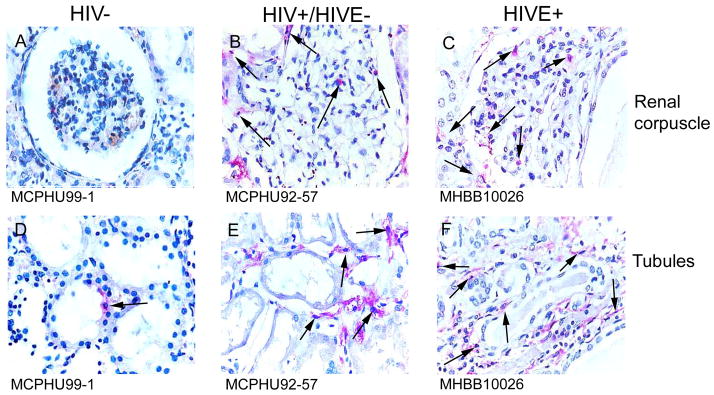

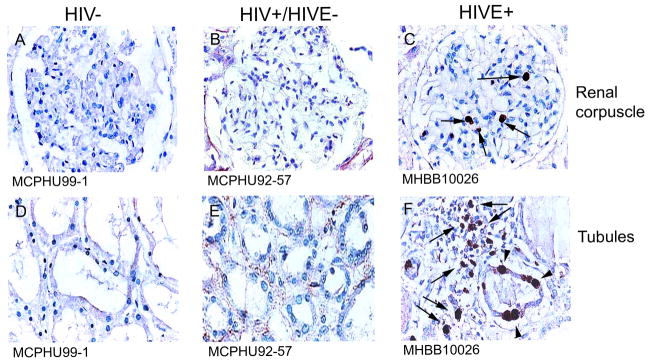

Immunohistochemical studies using antibodies against CD14 (Figure 7) and CD16 (Figure 8) show considerable MΦ accumulation around and within glomeruli and Bowman’s space, as well as around renal tubules, in patients with HIVE, as compared to HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis and seronegative individuals/controls. CD16+ cells are observed in renal tissue in some HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis (Figure 8, Panels B and E), however, to a much lesser degree than that seen in HIVE (Figure 8, Panels C and F). Rare tubulointerstitial CD16 positivity is observed in kidney from seronegative individuals (Figure 8, Panel D). These CD16+ cells are most likely MΦs, as CD14 and CD68 (data not shown) demonstrate a similar staining pattern. Quantitation of CD68 immunopositivity showed a significant increase in HIVE kidney, relative to seronegative/control tissue, while the frequency of CD68+ cells in HIV/AIDS without encephalitis was intermediate, but not significantly different between the two groups (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Ki-67 positivity is seen in kidney from HIVE cases but not HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis

Immunohistochemical studies revealed Ki-67+ cells in kidney tissue from patients with HIVE but not in HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis. Ki-67 positivity was most often seen in the glomeruli and the tubular epithelium (Figure 10, Panels C and F, arrowheads). In a single HIVE case, Ki-67 positivity was observed in cells constituting the interstitial infiltrate in kidney (Figure 10, Panel F, arrows).

Figure 10.

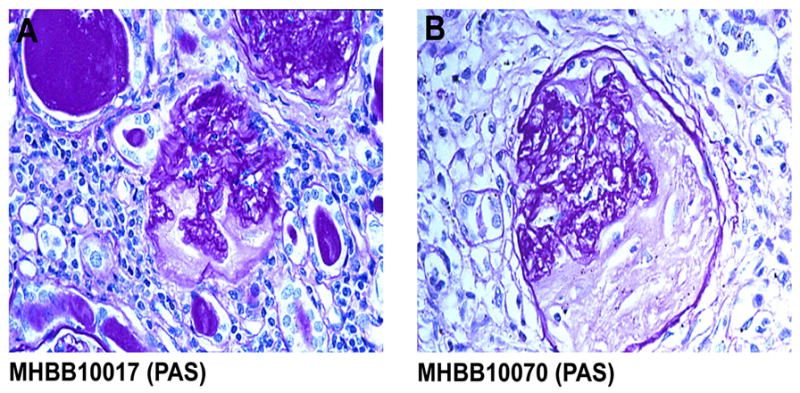

Evidence of kidney pathology is seen in patients with HIVE

Autopsy tissue from eight cases of HIVE was reviewed for evidence of renal pathology. Two cases with significant autolysis showed no specific pathology (Table 1). The remaining six cases demonstrated renal pathology consistent with chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (n=4) (Figure 11) and HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) with diffuse interstitial inflammation (n=2) (Table 1). In the four cases of tubulointerstitial nephritis, the constellation of interstitial inflammation, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy was suggestive of a chronic pyelonephritis. Although data were limited, there was no documented clinical history or laboratory evidence of urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis.

Figure 11.

CONCLUSIONS

Mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) play critical roles in innate and adaptive immunity, tissue remodeling, and homeostasis, but MP accumulation has also been associated with the development of injury in several diseases including diabetes, atherosclerosis, obesity, and certain cancers [9–13] and accordingly such mechanisms could contribute to comorbid conditions in the setting of HIV infection, including CNS disease. The number of brain MΦs has been shown to correlate better with the severity of neurocognitive impairment than the amount of virus in HIV infected subjects with HIV-D and HIVE [1]. The accumulation of MΦs in HIVE does not appear to be due to local MΦ/microglial proliferation, suggesting significant invasion of monocytes/MΦs from the peripheral blood into the CNS compartment [5]. Our previous work has shown that a monocyte subset expanded in HIV infection is phenotypically similar to cells that accumulate in HIVE brain [2–4,14]. This subset, which is CD16+, is associated with pathological hallmarks of HIVE, in which they comprise perivascular cuffs and nodular lesions and appear to be the principle reservoir of productive HIV infection in the CNS [4]. Together, these data prompted us to question whether brain-specific triggers promoted monocyte/MΦ entry into the CNS in some individuals with HIV infection, resulting in HIV-D and HIVE, or if CD16+ monocytes/MΦs invade and accumulate in tissues outside of the CNS.

In this immunohistochemical study, we show a significant increase in the number of CD16+ and CD68+ MPs in certain visceral tissues of patients with HIVE, as compared to seronegative controls, with intermediate accumulation in HIV/AIDS without encephalitis. Based on their number and location in the tissues examined, CD16+ MPs may represent a more tissue-invasive cell than those without CD16 expression. In HIVE lymph node, abundant CD16 expressing cells are present in the marginal zones, as well as within the germinal centers, and an increase in the number of CD16 expressing cells is also found in the subcapsular infiltrate. Additionally, HIVE spleen white pulp demonstrated abnormal accumulation of CD16+ cells that appear to have invaded from the red pulp, where the marginal zones of the white pulp have a greater number of CD16+ cells than the periarterial lymphocyte sheath. Although the total number of MΦs does not appear to increase in the liver parenchyma in HIVE, perivascular accumulation of CD16+ cells is observed, reminiscent of perivascular cuffing observed in the CNS of patients with HIVE. The increased frequency of CD16+ circulating monocytes in HIV/AIDS and HIV-D [2,3], combined with the observed increase of CD16+ MPs in tissues, may suggest increased monocyte/MΦ production and/or prolonged longevity of these cells.

In addition to our results showing accumulation of MΦs in visceral tissues, the absence of CD14 staining was striking within spleen in HIVE. Soluble CD14 (sCD14) is increased in plasma of HIV infected individuals and appears to correlate with mortality in AIDS [15], as well as neurocognitive impairment [4,16]. As such, our results may suggest the spleen is a site of CD14 cleavage and/or a potential source of sCD14. Further, sCD14 may contribute to immunologic and neurocognitive impairment in HIV, possibly through amplification of LPS responses [17]. It is worth noting that splenectomy has been demonstrated to increase survival time to AIDS, reduce viral loads, and increase CD4+ T cell counts [18,19]. While the interaction between the spleen and T cell and/or viral dynamics are not well-understood, the loss of CD14 antigen we observe in HIVE spleen may provide a novel insight into this interaction and suggest new avenues for investigation and HIV therapy.

In this small series, we observed a high prevalence of renal pathology, including prominent interstitial inflammation, among patients with HIVE. MPs infiltrating kidney tissue share similarities to the MPs that infiltrate the CNS in the setting of HIVE, possibly suggesting a common pathogenic mechanism. We previously reported significant accumulation of CD14+/CD16+ MPs in the CNS of patients with HIVE, as compared to the CNS of HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis and seronegative controls [4]. Here, we report dense accumulation of phenotypically similar MPs in kidney tissue of patients with HIVE as compared to patients with HIV/AIDS without encephalitis, with minimal MPs observed in seronegative controls. The majority of MPs are seen surrounding glomeruli and tubules, with fewer cells observed within the glomeruli. There are also large numbers of these cells observed around blood vessels, which may suggest invasion from the periphery. Kidney tissues from HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis demonstrated a moderate number of cells that express CD16 and CD68, with a more marked increase observed in kidney tissue from patients with HIVE.

In addition to leukocyte invasion, we observed positive Ki-67 staining in tubular epithelial cells and in unidentified cells in the glomeruli of HIVE kidney tissues, suggesting cellular proliferation. Ki-67 expression was not seen in kidney tissue from HIV/AIDS patients without encephalitis nor from seronegative controls. Tubular epithelial cell proliferation has been previously reported in HIVAN [20]. Ki-67+ cells seen in the glomeruli may represent cells present in the blood vessel lumen, which we have observed in other tissues, and/or mesangial cells, known to proliferate in HIVAN [21]. Alternatively, rare Ki-67+ cells seen in Bowman’s space may be proliferating podocytes or parietal epithelial cells, also consistent with reported features of HIVAN [22,23]. Despite the prominent interstitial inflammation observed in kidney tissue from six of the eight HIVE cases, Ki-67 staining suggested local proliferation of infiltrating cells in only one case.

The presence of HIV-1 DNA has been reported in kidney biopsies obtained from patients diagnosed with HIVAN [24,25]. In our study of archival autopsy tissues, however, we did not observe productive HIV-1 infection of the leukocyte infiltrate by HIV-1 p24 antigen detection, using signal amplification techniques. This may reflect differences in patient population, techniques used and/or tissue source/preparation, and/or small sample size and integrity of the specimens.

Even in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), chronic kidney disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among HIV infected individuals [26]. Pathological features of HIVAN, the kidney pathology most closely linked to HIV infection, include focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, tubular dilatation, and interstitial inflammation and fibrosis [27]. In our investigation of kidney tissue from patients with HIVE, we observed renal pathology consistent with HIVAN in two of eight cases. Other renal pathologies associated with HIV-1 infection, including immune complex nephropathies [28], were not observed in the HIVE kidney tissues in this small study.

In a previous study investigating the spectrum of renal pathology among patients with advanced HIV disease in the MHBB cohort, the most common renal abnormalities were arterionephrosclerosis, HIVAN, and glomerulonephritis, with other diagnoses, including chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, occurring less frequently [29]. In the current series of eight patients with HIVE from the same cohort, the distribution of renal pathology was different, with chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis observed at a higher frequency than HIVAN. Regardless of the primary renal diagnosis, interstitial inflammation was a prominent feature in the majority of cases. Previous studies have demonstrated that interstitial leukocytes are extremely numerous in HIVAN when compared with kidney tissues from patients with heroin-associated nephropathy and idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [30]. Future studies should consider whether the activated MPs observed in both the CNS and kidney of patients with HIVE represent common pathways leading to the pathogenesis of HIVE and interstitial inflammation in the kidney.

As in HIVE [1], MΦ number and activation status have been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases of the kidney [31]. The accumulation of phenotypically similar MPs observed in both the CNS and kidney of patients with HIVE may suggest a role for these cells in the pathogenesis of these AIDS-related complications; however, additional studies are necessary to clarify this role. It is worth noting that the initiation of cART has been shown to reverse or slow the progression of HIVAN [25] and has also been shown to reverse symptoms of HIV-D [32,33]. Current treatment recommendations advocate initiation of cART promptly upon a diagnosis of HIVAN [34]. Similarly, cART is an important treatment consideration for patients with HIV-D (HRSA Guide for HIV/AIDS Clinical Care, January 2011) [35]. It is likely that therapeutic strategies targeting HIV replication and/or the monocyte/MΦ may have efficacy for the treatment of both cognitive and renal disorders associated with HIV infection. The notion that MΦ accumulation in HIV infection is a global phenomenon is further supported by a recent cardiac study in SIV infected monkeys [36]. In view of possible common mechanisms, earlier treatment intervention may reduce comorbidities in HIV infection affecting both kidney and brain (and potentially other organs) and may be beneficial even in the setting of subtler neurocognitive and/or kidney disorders. Strategies targeting monocyte/MΦ homeostasis, tissue invasion, and innate immune polarization may have broad implications for the treatment of inflammatory diseases of the kidney and CNS, but may also have broad application in treating HIV associated co-morbidities as well as immunologic dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

Grants: RO1 NS047031 (JR); RO1 NS063605 (TF); PO1 DK056492 (CMW and VDD); U24MH100931 (SM)

This work was supported by grants R01MH090910 and R01NS047031 to JR. This work was also supported by the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank, R24MH59724 (Susan Morgello, Principal Investigator) as well as the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center, P30MH092177, (Kamel Khalili, PI, and Mary Barbe, Core Co-Leader, Basic Science Core II).

References

- 1.Glass JD, Fedor H, Wesselingh SL, McArthur JC. Immunocytochemical quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus in the brain: correlations with dementia. Ann Neurol. 1995;38(5):755–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulliam L, Gascon R, Stubblebine M, McGuire D, McGrath MS. Unique monocyte subset in patients with AIDS dementia. Lancet. 1997;349(9053):692–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer-Smith T, Tedaldi EM, Rappaport J. CD163/CD16 coexpression by circulating monocytes/macrophages in HIV: potential biomarkers for HIV infection and AIDS progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24(3):417–21. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer-Smith T, Croul S, Sverstiuk AE, et al. CNS invasion by CD14+/CD16+ peripheral blood-derived monocytes in HIV dementia: perivascular accumulation and reservoir of HIV infection. J Neurovirol. 2001;7(6):528–41. doi: 10.1080/135502801753248114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer-Smith T, Croul S, Adeniyi A, et al. Macrophage/microglial accumulation and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in the central nervous system in human immunodeficiency virus encephalopathy. The American journal of pathology. 2004;164(6):2089–99. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherberich JE, Nockher WA. Blood monocyte phenotypes and soluble endotoxin receptor CD14 in systemic inflammatory diseases and patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(5):574–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.5.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgello S, Gelman BB, Kozlowski PB, et al. The National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium: a new paradigm in brain banking with an emphasis on infectious disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27(4):326–35. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Shatti T, Barr AE, Safadi FF, Amin M, Barbe MF. Increase in inflammatory cytokines in median nerves in a rat model of repetitive motion injury. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;167(1–2):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193(6):727–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell IK, Rich MJ, Bischof RJ, Hamilton JA. The colony-stimulating factors and collagen-induced arthritis: exacerbation of disease by M-CSF and G-CSF and requirement for endogenous M-CSF. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68(1):144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patsouris D, Li PP, Thapar D, Chapman J, Olefsky JM, Neels JG. Ablation of CD11c-positive cells normalizes insulin sensitivity in obese insulin resistant animals. Cell Metab. 2008;8(4):301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzumura A. Neuron-microglia interaction in neuroinflammation. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2013;14(1):16–20. doi: 10.2174/1389203711314010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer-Smith T, Bell C, Croul S, Lewis M, Rappaport J. Monocyte/macrophage trafficking in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome encephalitis: lessons from human and nonhuman primate studies. J Neurovirol. 2008;14(4):318–26. doi: 10.1080/13550280802132857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandler NG, Wand H, Roque A, et al. Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(6):780–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons JL, Uno H, Ancuta P, et al. Plasma sCD14 is a biomarker associated with impaired neurocognitive test performance in attention and learning domains in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(5):371–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182237e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hailman E, Vasselon T, Kelley M, et al. Stimulation of macrophages and neutrophils by complexes of lipopolysaccharide and soluble CD14. J Immunol. 1996;156(11):4384–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsoukas CM, Bernard NF, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Effect of splenectomy on slowing human immunodeficiency virus disease progression. Arch Surg. 1998;133(1):25–31. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernard NF, Chernoff DN, Tsoukas CM. Effect of splenectomy on T-cell subsets and plasma HIV viral titers in HIV-infected patients. J Hum Virol. 1998;1(5):338–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Gubler MC, Beaufils H. Dysregulation of podocyte phenotype in idiopathic collapsing glomerulopathy and HIV-associated nephropathy. Nephron. 2002;91(3):416–23. doi: 10.1159/000064281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz MM, Korbet SM, Rydell J, Borok R, Genchi R. Primary focal segmental glomerular sclerosis in adults: prognostic value of histologic variants. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25(6):845–52. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barisoni L, Mokrzycki M, Sablay L, Nagata M, Yamase H, Mundel P. Podocyte cell cycle regulation and proliferation in collapsing glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2000;58(1):137–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shankland SJ, Eitner F, Hudkins KL, Goodpaster T, D’Agati V, Alpers CE. Differential expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in human glomerular disease: role in podocyte proliferation and maturation. Kidney Int. 2000;58(2):674–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanji N, Ross MD, Tanji K, et al. Detection and localization of HIV-1 DNA in renal tissues by in situ polymerase chain reaction. Histology and histopathology. 2006;21(4):393–401. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winston JA, Bruggeman LA, Ross MD, et al. Nephropathy and establishment of a renal reservoir of HIV type 1 during primary infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):1979–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adih WK, Selik RM, Xiaohong H. Trends in Diseases Reported on US Death Certificates That Mentioned HIV Infection, 1996–2006. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011;10(1):5–11. doi: 10.1177/1545109710384505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Agati V, Appel GB. Renal pathology of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18(4):406–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen AH, Nast CC. HIV-associated nephropathy. A unique combined glomerular, tubular, and interstitial lesion. Mod Pathol. 1988;1(2):87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyatt CM, Morgello S, Katz-Malamed R, et al. The spectrum of kidney disease in patients with AIDS in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Kidney Int. 2009;75(4):428–34. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Agati V, Suh JI, Carbone L, Cheng JT, Appel G. Pathology of HIV-associated nephropathy: a detailed morphologic and comparative study. Kidney Int. 1989;35(6):1358–70. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duffield JS. Macrophages and immunologic inflammation of the kidney. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30(3):234–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milazzo L, Menzaghi B, Corvasce S, et al. Safety of statin therapy in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(2):258–60. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181142e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCutchan JA, Wu JW, Robertson K, et al. HIV suppression by HAART preserves cognitive function in advanced, immune-reconstituted AIDS patients. Aids. 2007;21(9):1109–17. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280ef6acd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szczech LA. Monitoring HIV patients’ kidney function in clinical practice. What is known about kidney disease in other clinical contexts can help guide HIV care providers in monitoring kidney function in their patients. J Watch AIDS Clin Care. 2009;21(11):92–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agins B, Bacon O, Balano K, et al. HHS, editor. Guide for HIV/AIDS Clinical Care. Washington, D.C: 2011. p. 611. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker JA, Sulciner ML, Nowicki KD, Miller AD, Burdo TH, Williams KC. Elevated Numbers of CD163 Macrophages in Hearts of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Monkeys Correlate with Cardiac Pathology and Fibrosis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014 doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]