Abstract

In a prior study (Stein et al., 2013), we reported that rats pre-exposed to delayed rewards made fewer impulsive choices, but consumed more alcohol (12% wt/vol), than rats pre-exposed to immediate rewards. To understand the mechanisms that produced these findings, we again pre-exposed rats to either delayed (17.5 s; n = 32) or immediate (n = 30) rewards. In post-tests, delay-exposed rats made significantly fewer impulsive choices at both 15- and 30-s delays to a larger, later food reward than the immediacy-exposed comparison group. Behavior in an open-field test provided little evidence of differential stress exposure between groups. Further, consumption of either 12% alcohol or isocaloric sucrose in subsequent tests did not differ between groups. Because Stein et al. introduced alcohol concentration gradually (3–12%), we speculate that their group differences in 12% alcohol consumption were not determined by alcohol’s pharmacological effects, but by another variable (e.g., taste) that was preserved as an artifact from lower concentrations. We conclude that pre-exposure to delayed rewards generalizes beyond the pre-exposure delay; however, this same experimental variable does not robustly influence alcohol consumption.

Keywords: impulsive choice, delay discounting, alcohol, sucrose, open field, lever press, rat

Across species, impulsive choice has been operationalized as preference for smaller, relatively immediate rewards over larger, more delayed rewards (e.g., Ainslie, 1975). In human cross-sectional studies (e.g., comparisons of alcoholics vs. controls), impulsive choice in laboratory tasks is strongly associated with substance-use disorders (for meta-analysis, see MacKillop et al., 2011). One account of this relation is that impulsive choice plays an etiological role in the development of substance-use disorders, as a generalized tendency to over-value immediate outcomes (or devalue delayed outcomes) might be expected to produce persistent preference for immediate drug effects over the delayed benefits of abstinence (e.g., long-term good health; for review, see Perry & Carroll, 2008; Stein & Madden, 2013). Some evidence supports this interpretation, as impulsive choice in longitudinal studies has been shown to precede and predict subsequent adoption of tobacco, cocaine, and alcohol use (e.g., Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009; Kim-Spoon, McCullough, Bickel, Farley, & Longo, 2014; Khurana et al., 2013), indicating that the relation between impulsive choice and substance-use disorders cannot be solely explained as a consequence of prior drug exposure.

Rodent studies have yielded relations between impulsive choice and drug self-administration at least formally consistent with the human longitudinal data reviewed above. That is, impulsive choice in screening tasks has been shown to precede and predict greater self-administration of a range of drugs, including alcohol, cocaine, nicotine, and methylphenidate (e.g., Diergaarde et al. 2008; Koffarnus & Woods, 2013; Marusich & Bardo, 2009; Perry, Larson, German, Madden, & Carroll, 2005; Poulos, Le, & Parker, 1995; for review, see Stein & Madden, 2013). Despite these naturally occurring relations, few rodent studies have been designed to determine whether experimental changes in impulsive choice yield predictable changes in drug self-administration. If experimental reductions in impulsive choice produce concomitant reductions in drug self-administration, a direct causal relation between these variables would be strengthened. In translation, this finding would suggest that treating impulsivity in human populations would yield therapeutic effects on substance-use disorders. If, however, experimental reductions in impulsive choice do not reliably reduce drug self-administration, then the naturally occurring relation between these variables may owe to the mutual influence of a third, unexamined variable (biological or behavioral).

Adopting the experimental logic above, Stein et al. (2013) experimentally reduced impulsive choice in rats (via prolonged pre-exposure to delayed rewards) in order to examine whether this change produced a concomitant reduction in alcohol consumption. These authors pre-exposed two experimental groups to sessions in which food was available from a single lever following either fixed (17.5 s; n = 14) or escalating (17.5 – 44 s, on average; n = 16) delays. In subsequent testing, both experimental groups more frequently preferred a larger, later reward (LLR; three pellets, delayed by 15 s) over a smaller, sooner reward (SSR; one pellet, delivered immediately) than a comparison group pre-exposed to immediate rewards (n = 14). However, when these authors examined alcohol consumption across ascending concentrations (3% – 24%), the group pre-exposed to fixed delays, although less impulsive, consumed significantly more alcohol at a 12% concentration than the comparison group exposed to immediate reward1. The direction of this effect counters the naturally occurring relation between these variables (e.g., Poulos et al., 1995); however, interpreting these data requires further investigation. In the present study, we sought to address two variables that may have been responsible for this finding.

First, a large experimental literature documents that chronic stress, particularly during adolescence, increases alcohol consumption in rodents (for review, see Becker, Lopez, & Doremus-Fitzwater, 2011). If one assumes delay to reward is a stressor, then chronic pre-exposure to this putative stressor might be expected (independent of its effects of on impulsive choice) to increase subsequent alcohol consumption. Few studies, however, have examined delay as a possible source of stress in rodents. In at least one study, acute exposure to a prolonged (15 min), non-operant delay to highly palatable food was shown to increase the stress hormone, corticosterone, in rats (Cifani, Polidoro, Melotto, Ciccocioppo, & Massi, 2009). However, these authors’ specific methodology (e.g., acute delay exposure in a model of “yo-yo” dieting) may limit the generality of this effect across experimental paradigms and its relevance to the data reported by Stein et al. (2013). Further study is required to estimate the potential role of stress in the effects of delay pre-exposure on alcohol consumption.

Second, Stein et al. (2013) examined alcohol consumption under ascending alcohol concentrations, a preparation designed to match prior studies in the literature (e.g., Poulos et al., 1995). A problem here is the degree to which this choice may have introduced sources of variance (e.g., taste) into data collection that were unrelated to alcohol’s pharmacological effects. Indeed, such concern is warranted, as reanalysis of Stein et al.’s data indicates that likely subpharmacological consumption at 3% alcohol (approximately 0.1–0.2 g/kg/30 minutes, on average) significantly predicted consumption at the 12% concentration at which group differences emerged (r = .59, p < .001; n = 44). Thus, it appears the variable(s) that determined consumption of 12% alcohol were preserved as an artifact from the 3% concentration. As a result, the degree to which delay pre-exposure increases rats’ preference for alcohol’s pharmacological effects, independent of the influence of extra-pharmacological properties experienced at lower concentrations, has yet to be determined. To this end, examining consumption of 12% alcohol in isolation is necessary. Moreover, examining consumption of a sucrose solution in a separate test is necessary to estimate the influence of delay pre-exposure on preference for sweet substances in the absence of pharmacological effects.

Aside from the specific concerns outlined above regarding Stein et al.’s (2013) data, variables that impact impulsive choice are of broad interest to those studying impulsive choice and its relation to addiction and other pathologies (e.g., ADHD; Scheres, Tontsch, & Thoeny, 2013). To this end, we sought in the present study to provide a more thorough examination of the effects of delay pre-exposure on impulsive choice than that provided by Stein et al. Because Stein et al. tested impulsive choice under only a single non-zero LLR delay (15 s) the degree to which the effects of pre-exposure may generalize to longer delays is unclear. In addition, little is known about the mechanism(s) by which delay pre-exposure exerts its effects on impulsive choice. To this end, examination of secondary behavioral measures (e.g., response latency, time spent visiting the food receptacle during delays), and determining how such measures relate to impulsive choice, may provide important clues. For example, if delay pre-exposure reduces impulsive choice by altering timing processes, then this may be evident in the temporal pattern of food receptacle visits during delays in the impulsive choice test. In turn, such secondary analyses are likely to inform future research designed explicitly to investigate functional mechanisms underlying the effects of delay pre-exposure on impulsive choice.

In light of the concerns and considerations outlined above, we sought to systematically reproduce and extend the effects of delay pre-exposure on impulsive choice and alcohol consumption reported by Stein et al. (2013). Two groups of Long-Evans rats were pre-exposed to either a fixed delay to food rewards2 (17.5 s; n = 32) or immediate food rewards (n = 30). In these delay-exposed (DE) and immediacy-exposed (IE) rats, we examined a variety of behavioral measures: (1) potential behavioral indicators of prior stress exposure in an open-field test (e.g., exploration of the open field, motor activity, defecation; Colorado et al., 2006; Katz et al., 1981), (2) impulsive choice under both 15-s and 30-s LLR delays, including secondary behavioral measures of response latency (a potential measure of motivation), time spent in the food receptacle during delays (a possible measure of mediating behavior), and temporal patterns of intra-delay receptacle visits (a potential measure of timing), (3) consumption of 12% wt/vol alcohol and isocaloric sucrose (in separate tests), and (4) impulsive choice in a retest, more than two months following the initial test.

Method

Subjects

All animals were maintained under the standards of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Utah State University. Subjects were 63 experimentally naïve, male Long-Evans rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN), received at the facility at postnatal day (PND) 21. Rats were individually housed in polycarbonate cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled colony room. Lights in the colony operated on a 12-hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m.). Water was freely available in all home cages.

Rats were randomly assigned to either DE (n = 32) or IE (n = 31) groups. One IE rat died of natural causes early in training, leaving only 30 rats in the IE group. Following three days of ad-libitum food access, rats were weighed daily and restricted to 85% of the vendor-supplied, age-adjusted free-feeding weight. Food restriction continued until 14 days prior to open-field, alcohol and sucrose tests, at which point rats were provided with ad-libitum food access in their home cages. Following alcohol and sucrose testing, food restriction was reinstated using rats’ 85% free-feeding weights (recalculated from free-feeding weights 12–14 days following the final alcohol or sucrose session).

Unless otherwise specified below, experimental sessions were conducted seven days per week between the hours of 7:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. Sessions were conducted at approximately the same time each day, with DE and IE rats counterbalanced across time of day.

Apparatus

Thirty identical operant conditioning chambers were used (24.1×30.5×21 cm; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Each chamber was housed within a sound-attenuating box outfitted with a white-noise speaker. Centered on the rear wall of the chamber and 6.5 cm above the chamber’s grid floor was a retractable response lever. Two identical retractable levers were located at the same height on the front wall, one to the left and one to the right of the rear lever. Directly above all three levers was a 28-V DC cue light. A pellet feeder delivered grained based pellets (45 mg; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) to a receptacle centered below the two front wall levers.

Sixteen polycarbonate cages, identical to those in which the rats were housed, were used in the alcohol and sucrose tests. Each cage was equipped with two drinking tubes (Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA), located above a small glassware bowl (Pyrex; World Kitchen, LLC, Rosemount, IL) used to collect leakage. Alcohol and sucrose tests occurred in a room equipped with a white-noise speaker and illuminated by a 40W red light.

An open-field arena was used to measure exploratory behavior. The arena (41 cm×41 cm×41 cm) consisted of four black acrylic walls and a white acrylic floor. Testing occurred within a room equipped with a white-noise speaker and illuminated with approximately 60 lux of ambient light at the level of the arena floor. All sessions were recorded using a digital video camera (Logitech, Inc., Newark, CA) mounted 81 cm above the arena floor. Smart (ver. 3.0) video tracking software and manual scoring were used to analyze behavior.

Procedures

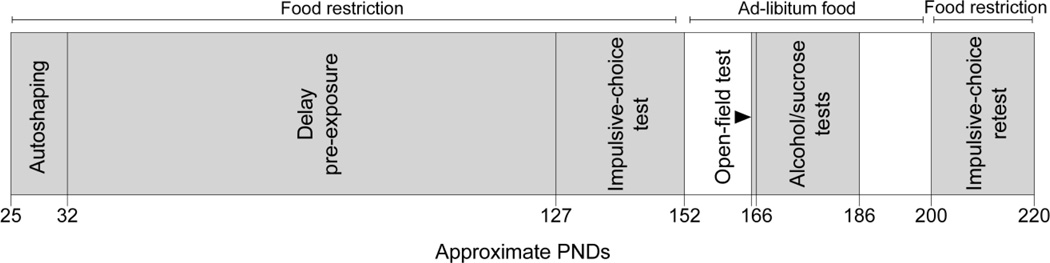

Figure 1 illustrates the order and duration of all experimental phases, as well as the approximate age of rats during these phases.

Figure 1.

Order and approximate durations of experimental conditions, by age. Depicted durations of delay pre-exposure and the initial impulsive-choice test include side-lever and choice-training, respectively. Some durations varied slightly depending on sessions required to meet training criteria (see text; Table 1). White space indicates periods in which sessions were not completed.

Autoshaping

An autoshaping procedure was used to establish rear lever pressing. To produce comparable rates of acquisition across DE and IE groups, a constant ratio of intertrial interval to trial length of 11:1 was used (Gibbon, Baldock, Locurto, Gold, & Terrance, 1977). For DE and IE rats, the ITI was 247.5 and 55 s, respectively. During the ITI, no programmed stimuli were presented. Following the ITI, the rear-lever/light complex was activated (i.e., lever inserted and light illuminated) for 5 s. For DE rats, either a single response or termination of this 5-s period (whichever occurred first) deactivated the lever; the cue light remained illuminated for 17.5 s prior to delivery of two food pellets. For IE rats, deactivation of the lever and light occurred simultaneously and was contiguous with pellet delivery. Sessions consisted of 25 trials and continued until rats earned ≥ 90% of the scheduled rewards across two consecutive sessions.

Delay pre-exposure

All rats completed 90 sessions of delay pre-exposure; sessions were composed of 125 trials. Each trial began with the activation of the rear-lever/light complex. A single lever press deactivated the rear lever and initiated a delay to the delivery of two food pellets. This delay was 17.5 s for DE rats and 0.01 s [henceforth 0 s] for IE rats. In this and all subsequent phases, the cue light above the lever remained illuminated during the delay. If the rear lever was not pressed within 20 s of trial onset, the rear-lever/light complex was deactivated and the trial was scored as an omission. A variable-length ITI ensured that trials started every 50 s, regardless of rear-lever response latency or omissions.

Immediately following the 90 sessions of responding on the rear lever, all rats were briefly trained to respond on the two front-wall levers. Session structure and stimuli were identical to those used during delay pre-exposure, except that the rear lever was not used. Instead, either the left or right (determined randomly without replacement every two trials) front-lever/light complex was activated at the beginning of every trial. Front-lever training continued until rats completed ≥ 90% of programmed trials for two consecutive sessions.

Choice-training and impulsive-choice test

Prior to the impulsive-choice test, all rats completed choice training in order to ensure sensitivity to reward amount (e.g., Evenden & Ryan, 1996). Choice-training sessions consisted of three blocks of 20 trials, with each block separated by a 7-min blackout period. Each block consisted of six forced-choice trials (only one front lever available; left-right order determined randomly, as described above) and 14 free-choice trials (both front levers available). At the beginning of all trials, the rear-lever/light complex was activated. A single response deactivated the complex and activated one or both front-lever/light complexes, depending on trial type (forced or free choice). A single response on a front-wall lever deactivated both levers and initiated a delay to the delivery of food; the cue light above the selected lever remained on during the delay, while the unselected cue light was turned off. One lever produced a 1-pellet reward whereas the other delivered 3 pellets; sides counterbalanced within and between groups. Within each group, the delay to both rewards was the same; however, these delays differed between groups (as before, 17.5 s in DE rats and 0 s in IE rats). Failures to respond within 20 s of lever insertion terminated the trial and were counted as omissions. Sessions continued until rats chose the larger reward on ≥ 90% of the trials and made no more than five omissions during two consecutive sessions.

Following choice training, impulsive choice was assessed for all rats using a within-session, increasing-delay procedure (Evenden & Ryan, 1996). Sessions were identical to those described for choice training with the following exceptions: (a) the 1-pellet reward was delivered immediately; (b) the delay to the 3-pellet reward increased across the three trial blocks (0, 15, and 30 s); and (c) to ensure continued sensitivity to differences in reward amount, two probe sessions (0-s delays across trial blocks) were pseudo-randomly interspersed among those of the impulsive-choice test. Rats completed 20 total sessions in the impulsive-choice test, with no probe sessions programmed over the final six sessions.

Open-field test

Upon completion of the impulsive-choice test, rats were provided with ad-libitum food in the home cage for 14 days. On the 13th day of ad-libitum food, the rat was placed in the middle of the open-field arena and its movements were tracked for 10 minutes (e.g., Colorado et al., 2006; Spivey et al., 2009). Testing took place between 7:00 and 9:00 a.m.

Alcohol and sucrose tests

All rats were matched into pairs based on a summary measure of impulsive choice (AUC; Myerson, Green, & Warusawitharana, 2001). From each pair, one rat was randomly assigned to complete alcohol sessions; the other rat was assigned to complete sucrose sessions. The sample size used in this study was chosen so that the alcohol and sucrose conditions would contain numbers of rats (n = 16 and 15 DE and IE rats, respectively) similar to those used by Stein et al. (2013; n = 14, each group).

Alcohol and distilled water were mixed to a 12% wt/vol solution every 1–2 days. Sucrose and distilled water were mixed daily to a 21% wt/vol solution (isocaloric to alcohol). Alcohol and sucrose tests consisted of 20 daily, 30-min sessions. Each subject’s assigned test solution and water were poured into separate drinking tubes, with the placement side of the solution and water alternating daily. Following each session, the pre-post difference in weights (0.01-g resolution) of each drinking tube was recorded. Leakage, if present, was weighed and subtracted from consumption measures.

Impulsive-choice retest

Following completion of the alcohol or sucrose tests, rats continued to receive ad-libitum food in their home cages for 14 days prior to the reinstatement of food restriction. Following this period, the impulsive-choice retest was conducted as described for the initial test, except that no choice-training sessions were conducted.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS (ver. 21, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

For autoshaping, front-lever training, and choice training, the dependent measures were days to meet the training criteria. For delay pre-exposure, the 90 sessions were divided into 15, six-session blocks. Dependent measures at each session block included: rear-lever latency (s), percent trials omitted, and total time spent visiting the pellet receptacle during delays (measured by continuous 0.01-s beam breaks). An index of curvature was also examined in order to describe temporal patterns of receptacle visits during delays. To calculate this index, the 17.5-s delay was divided into 35 half-second intervals. Cumulative time spent in the receptacle across intervals was then applied to the following equation (Fry, Kelleher, & Cook, 1960; e.g., Ward & Odum, 2005):

| (1) |

in which C represents curvature and T represents cumulative time in the receptacle through interval i or through the final interval n. This measure (C) is bounded symmetrically around 0 by discrete negative and positive values, but these bounds vary as a function of the number of intervals (n) used in Equation 1. Thus, in order to make comparisons across delays of different durations, observed values were converted to a normalized measure (Cn) by dividing observed C by the fraction: (n-1)/n. Calculated using this method, Cn describes a continuum in which, at the extremes, time is spent in the receptacle only in the first interval (Cn = −1) or only in the last interval (Cn = 1). When Cn = 0, time in the receptacle is evenly distributed across the intervals.

In the impulsive-choice test and retest, data were taken from the final six sessions. Dependent measures at each delay were percent LLR choice, rear-lever latency, and percent trials omitted. Front-lever latencies were not examined because many rats displayed exclusive or near-exclusive LLR or SSR preference in free-choice trials at one or more delays, thus restricting the data available for group comparisons. Finally, time spent in the receptacle and Cn (as described previously) were examined during 15- and 30-s LLR forced-choice trials (to which all rats were exposed, regardless of free-choice preference).

In the open-field test, the 10-min session was divided into 5, two-min blocks. Dependent measures at each block included entries into the center field (defined via software as an inner square comprising 25% of the total area) and distance traveled (m). Additional global measures included defecation count (number of fecal boluses) and defecation latency (min). Instances in which rats did not defecate during the session were coded as a 10-min latency (the length of the session).

In the alcohol and sucrose tests, the 20 sessions were divided into 4, five-session blocks. Dependent measures at each block included consumption of the test solution (alcohol or sucrose; g/kg), a preference score for the test solution (g solution/mL water consumed), and body weight.

Many of the measures described above were non-normally distributed (bimodality or skew) and not amenable to transformation. Where skew was evident in dependent measures, group medians (± interquartile range) are presented in figures; in all other cases, group means (± SEM) are presented. Due to violations of normality, all non-repeated measures within individual tests (days to criterion during autoshaping, front-lever and choice training, defecation data) were analyzed using nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests. All repeated measures (those within delay pre-exposure, as well as impulsive-choice, open-field, and alcohol or sucrose tests) were analyzed using separate generalized estimating equations (GEEs; one for each measure, unless otherwise specified). Use of GEE allows for analysis of correlated, repeated measures; but unlike ANOVA, use of GEE makes no distributional assumptions (for overview, see Ballinger, 2004).

Unless otherwise specified, GEE models included group as the between-subjects factor and one within-subjects factor relevant to the test (e.g., session block during delay pre-exposure and alcohol or sucrose tests; delay during impulsive-choice tests). Because time in the receptacle and Cn could not be derived for IE rats during delay pre-exposure, only the within-subjects factor (session block) was examined. Likewise, because time in the receptacle and Cn could not be derived in either group at the 0-s delay in the impulsive-choice test, only the 15- and 30-s delays were examined when analyzing these measures. In a GEE model examining test-retest changes in LLR choice, group was again the between-subjects factors (as in previous models); however, two within-subjects factors (delay and test) and a covariate (interim completion of either alcohol or sucrose testing) were included in the model. Where significant main effects or interactions were observed in all GEE models, post-hoc comparisons were examined at individual repeated-measures time points using sequential Bonferroni correction to control Type I error rate.

Finally, Spearman rho correlations were used to examine relations between LLR choice and the following measures in DE and IE rats: rear-lever latency, percent trials omitted, time in the receptacle, and Cn from the impulsive-choice tests; and center entries, distance traveled, and defecation count and latency from the open-field tests Spearman rho correlations were also used elsewhere, as reported below, to supplement group analyses.

Results

Autoshaping

Both groups required an equivalent median number of sessions to meet the rear-lever autoshaping criterion (see Table 1; U = 410; NS).

Table 1.

Median sessions to meet the training criterion (± interquartile range) during autoshaping, side-lever, and choice training in DE and IE rats.

| Training Condition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Autoshaping | Side-Lever | Choice |

| DE | 7.00 (4.25 – 8.75) | 6.00 (4.00 – 7.75)** | 4.00 (3.00 – 5.00)* |

| IE | 7.00 (6.00 – 9.00) | 4.00 (3.00 – 6.00) | 3.00 (2.00 – 4.00) |

Significantly different than IE rats:

p < .05,

p < .01.

Delay Pre-Exposure

Rear-lever latency and trial omissions

The upper two panels of Figure 2A depict rear-lever latency and percent trials omitted during delay pre-exposure. For latency, main effects of session block (Wald’s χ2 = 118.38; p < .001) and group (Wald’s χ2 = 67.36; p < .001) were observed, as well as a Group × Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 14.52; p < .001). Post-hoc comparisons at individual session blocks revealed significantly longer latencies in DE rats from session blocks 1–12 (p < .05 or lower; see Figure 2A) and no between-group differences from session blocks 13–15.

Figure 2.

Panel A: Rear-lever latency and percent trials omitted per session, and time in the receptacle and Cn per trial, across session blocks during delay pre-exposure. Panel B: Percent LLR choice across delays in the impulsive-choice test. Panel C: Rear-lever latency and percent trials omitted per session, and time in the receptacle and Cn per trial, across delays in the impulsive-choice test. All panels: Where specified, data reflect median (± interquartile range) observed values; all remaining data reflect mean (± SEM) values. Data points have been slightly displaced on the x-axis, for clarity. Significantly different than IE rats: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

When percent trials omitted was examined, main effects of session block (Wald’s χ2 = 342.3; p < .001) and group (Wald’s χ2 = 69.76; p < .001) were observed, as well as a Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 39.27; p < .001). Post-hoc comparisons at individual session blocks revealed longer latencies in DE rats from session blocks 1–9 (p < .05 or lower; see Figure 2A) and no between-group differences from session blocks 10–15.

Time in the Receptacle and Cn

The lower two panels of Figure 2A depict time in the receptacle and Cn during delay pre-exposure. For DE rats, a main effect of session block was observed on time in the receptacle (Wald’s χ2 = 90.38; p < .001), with this measure rising to peak values by the 10th session block and remaining approximately stable through the final session block. Likewise, a main effect of session block was observed on Cn (Wald’s χ2 = 264.16; p < .001); however the relation between these variables was bitonic, with Cn rising to peak values by the fourth session block and declining to baseline levels by the tenth session block. The individual differences in Cn are addressed below.

Front-Lever and Choice Training

Rats in the DE group required significantly more sessions than IE rats to meet the front-lever and choice-training criteria (see Table 1; in both cases, U < 324; p < .05).

Impulsive-Choice Test

LLR choice

Figure 2B depicts percent LLR choice across delays in the impulsive-choice test. Choice was stable across the final six sessions analyzed, as no significant main effect of session on LLR choice, or Delay×Session interaction, was observed in any group (in all cases, Wald’s χ2 < 0.90; NS). Results of GEE revealed main effects of group (Wald’s χ2 = 34.24; p < .001) and delay (Wald’s χ2 = 593.26; p < .001) on LLR choice, as well as a Group × Delay interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 34.11; p < .001). Post-hoc comparisons revealed significantly greater LLR choice (collapsed across delay) in DE, compared to IE rats (p < .001). Comparisons at individual delays revealed greater LLR choice in DE, compared to IE rats, at both the 15- and 30-s LLR delays (in both cases, p < .001).

Response latency and trial omissions

The upper two panels of Figure 2C depict rear-lever response latency (s) and percent trials omitted across LLR delays. Results of GEE revealed significant main effects of delay on both latency and omissions (in both cases, Wald’s χ2 > 28.26; p < .001), but no main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 < 0.39; NS). Results further revealed a significant Group×Delay interaction for omissions (Wald’s χ2 = 12.41; p < .05), but not latency (Wald’s χ2 = 2.44; NS). Post-hoc comparisons revealed significantly fewer omissions in DE, than IE rats at the 15-s LLR delay (p < .05). Finally, LLR choice did not significantly correlate with measures of rear-lever latency or percent trials omitted at either the 15- or 30-s delay.

Time in the receptacle and Cn

The lower two panels of Figure 2C depict time in the receptacle and Cn across delays in the impulsive-choice test. For time in the receptacle, results of GEE revealed significant main effects of group (Wald’s χ2 = 4.49; p < .05) and delay (Wald’s χ2 = 137.09; p < .001), as well as a Group×Delay interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 10.90; p < .01). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that DE rats spent significantly more time in the receptacle than IE rats at the 30-s delay (p < .01), but not at the 15-s delay.

When Cn was examined, results of GEE revealed a significant main effect of delay (Wald’s χ2 = 9.98; p < .01) and no main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 = 0.79; NS), but a significant Group×Delay interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 4.89; p < .05). Post-hoc comparisons, however, revealed no between-group differences at either delay.

Table 2 provides correlations between LLR choice and measures of time in the receptacle and Cn in the impulsive-choice test. Significant positive correlations at both delays were observed between LLR choice in the first test of impulsive choice and the time that DE rats spent in the food receptacle; these correlations were not significant for IE rats. For Cn, a significant negative correlation was observed at the 15-s and 30-s delays in DE rats (i.e., rats that evenly distributed their time in the feeder during the delay tended to make more LLR choices than those that spent more time in the feeder at the end of the delay). In IE rats, this negative correlation was significant only at the 30-s delay.

Table 2.

Spearman rho correlations in DE and IE rats between LLR choice (15- and 30-s delays) and simultaneously collected measures of time in the receptacle and Cn in the impulsive-choice test and retest.

| Test | LLR Delay |

Time in Rec. | Cn | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | DE | IE | ||

| Test | 15 | .59** | .30 | −.45* | −.27 |

| 30 | .71*** | .32 | −.54** | −.50** | |

| Retest | 15 | .42 | .14 | −.20 | −.26 |

| 30 | .66*** | .15 | −.58** | −.16 | |

Bolded coefficients indicate statistical significance.

p < .05.

p < .01,

p < .001.

— indicates data unavailable for the retest.

Open-Field Test

Center entries and distance traveled

The left panels of Figure 3A depict center entries and distance traveled in the open-field test. A main effect of time was observed on center entries (Wald’s χ2 = 21.61; p < .001), but there was no main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 = 1.84; NS) or Group×Time interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 1.25; NS). In contrast, main effects of group (Wald’s χ2 = 7.09; p < .01) and time (Wald’s χ2 = 52.0961; p < .001) were observed on distance traveled, as well as a Group×Time interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 11.96; p < .05). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that DE rats were less active than IE rats in the second two-minute block (p < .05) but distance traveled was otherwise undifferentiated. Finally, LLR choices made at the 15- and 30-s delays (test or retest) did not significantly correlate with either of these open-field measures in DE or IE rats.

Figure 3.

Panel A: Center entries and distance traveled across two-minute blocks in the open-field test. Also depicted is defecation count and latency; in which horizontal lines within each box represent group medians; upper and lower box edges represent interquartile range; whiskers represent minimum and maximum values. Panels B and C: Consumption and body weight during the alcohol and sucrose tests. All panels: Where specified, panels reflect median (± interquartile range) observed values; all other panels reflect mean (± SEM) observed values. Data points have been slightly displaced on the x-axis, for clarity. Significantly different than DE rats: *p < .05.

Defecation count and latency

The right panels of Figure 3A depict defecation count and defecation latency in the open-field test. No differences between groups were observed in either of these measures (U > 424; NS). As before, 15- or 30-s LLR choice (test or retest) did not significantly correlate with either of these measures in DE or IE rats.

Alcohol and Sucrose Tests

Alcohol consumption, preference, and body weight

Figure 3B depicts alcohol consumption (g/kg) and corresponding body weight (g) across session blocks among rats assigned to this test. A main effect of session block was observed on consumption (Wald’s χ2 = 9.51; p < .05), but no main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 = 0.14; NS) or Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 6.63; NS).

Median alcohol preference scores (i.e., g solution/mL water consumed) across session blocks 1–5 (not pictured) ranged from 1.49 (IQR: 1.21 – 1.95) to 2.40 (IQR: 0.36 – 6.07) in DE rats and 1.32 (IQR: 1.15 – 1.75) to 2.26 (IQR: 0.14 – 1.72) in IE rats. Results of GEE revealed no main effect of session block (Wald’s χ2 = 1.83; NS) or group (Wald’s χ2 = 0.95; NS) on alcohol preference, nor was there a significant Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 0.99; NS).

Body weight significantly increased across session blocks (Wald’s χ2 = 124.39; p < .001), but weight was undifferentiated across groups (Wald’s χ2 = 3.27; NS) and there was no Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 2.66; NS).

Sucrose consumption, preference, and body weight

Figure 3C depicts sucrose consumption (g/kg) and corresponding body weight (g) for rats assigned to the test of sucrose consumption. No main effect of group was observed on consumption (Wald’s χ2 = 2.25; p = NS); however, a main effect of session block was observed (Wald’s χ2 = 80.80; p < .001), as well as a Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 17.82; p < .01). Post-hoc comparisons revealed no significant group differences in consumption at individual session blocks.

Median sucrose preference across session blocks 1–5 (not pictured) ranged from 9.88 (IQR: 6.40 – 15.70) to 50.88 (IQR: 31.90 – 112.60) in DE rats and 10.89 (IQR: 7.60 – 19.30) to 18.92 (IQR: 12.6 – 88.80) in IE rats. Results of GEE revealed a main effect of session block on sucrose preference (Wald’s χ2 = 34.83; p < .001), but no main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 = 0.70; NS) or Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 2.59; NS).

Again, a main effect of session block was observed on body weight (Wald’s χ2 = 122.10; p < .001), but no main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 = 0.07; NS) or Group×Session Block interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 8.94; NS).

Impulsive-Choice Retest

LLR choice

Figure 4A depicts percent LLR choice across delays in the impulsive-choice retest. As in the initial test, choice was stable across the final six sessions, as no main effect of session or Delay × Session interaction was observed in either group (in all cases, Wald’s χ2 < 0.76; NS). Results of GEE revealed main effects of group (Wald’s χ2 = 15.31; p < .001) and delay (Wald’s χ2 = 368.41; p < .001), as well as a Group×Delay interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 15.67; p < .001). Post-hoc comparisons revealed greater LLR choice in DE, compared to IE, rats at both the 15- (p < .001) and 30-s (p < .05) delays.

Figure 4.

Panel A: Median percent LLR choice (± interquartile range) across delays in the impulsive-choice retest. Panel B: Rear-lever latency and percent trials omitted per session, and time in the food receptacle and Cn per trial, across LLR delays in the impulsive-choice retest. Panel C: Percent LLR choice at the 15- and 30-s delays in the impulsive-choice test and retest. Gray lines indicate data for individual subjects. All panels: Where specified, panels reflect median (± interquartile range) observed values; all other panels reflect mean (± SEM) observed values. Data points have been slightly displaced on the x-axis, for clarity. Significantly different than IE rats: *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Choice in DE rats varied substantially, with interquartile ranges of 5.16 – 100% and 0.51 – 98.46% LLR choice at 15- and 30-s LLR delays, respectively. In contrast, choice in IE rats varied little; interquartile ranges were 0.00 – 6.12% and 0.00 – 1.65% LLR choice at 15- and 30-s LLR delays, respectively.

Response latency and trial omissions

The upper two panels of Figure 4B depict rear-lever response latency (s) and percent trials omitted across LLR delays. For both measures, results revealed a main effect of delay (in both cases, Wald’s χ2 >15.15; p < .001), but no main effect of group (in both cases, Wald’s χ2 < 0.88; NS) or Group×Delay interaction (in both cases, Wald’s χ2 < 1.64; NS). As in the initial impulsive-choice test, LLR choice did not significantly correlate with measures of rear-lever latency or percent trials omitted at either the 15- or 30-s delay.

Time in the receptacle and Cn

The lower two panels of Figure 4B depicts time in the receptacle and Cn across LLR delays. For time in the receptacle, results of GEE revealed main effects of group (Wald’s χ2 = 5.04; p < .05) and delay (Wald’s χ2 = 140.25; p < .001), as well as a Group×Delay interaction (Wald’s χ2 = 7.14; p < .01). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that DE rats spent more time in the receptacle than IE at the 30-s delay (p < .05), but not at the 15-s delay.

When Cn was examined, results of GEE revealed a main effect of group (Wald’s χ2 = 11.32; p < .01). While there was no main effect of delay (Wald’s χ2 = .31; NS), a Group×Delay interaction was observed (Wald’s χ2 = 5.99; p < .05). Post-hoc comparisons revealed larger Cn values in DE rats at the 15-s delay (p < .01), but not at the 30-s delay.

Table 2 provides correlations between LLR choice and measures of time in the receptacle and Cn in the impulsive-choice retest. For time in the receptacle, a significant positive correlation was observed at the 30-, but not 15-s, delay in DE rats. In contrast, no significant correlations were observed in IE rats. For Cn, a significant negative correlation was observed at the 30-, but not 15-s, delay in DE rats. Again, neither of these correlations was significant in IE rats.

Test-retest comparisons

Figure 4C depicts group and individual-subject comparisons between LLR choice in the impulsive-choice test and retest (for space, 0-s delays are not depicted). When test and retest were compared, there was no main effect of test (Wald’s χ2 = 1.33; NS); however, a Group×Test interaction was observed (Wald’s χ2 = 5.24; p < .05); specifically, post-hoc comparisons revealed a reduction in LLR choice (collapsed across delay) at the retest in DE rats (p < .05), but not in IE rats. No other two- or three-way interactions were observed (in both cases, Wald’s χ2 < 4.47; NS) and interim completion of either alcohol or sucrose testing was not a significant covariate (Wald’s χ2 > 0.19; NS). Despite individual-subject changes in choice depicted in Figure 4C, LLR choice was strongly correlated across tests at both the 15-s delay (DE: rho = .85; IE: rho = .69; ps < .001) and 30-s delay (DE: rho = .93; IE: rho = .80; ps < .001).

Discussion

The results of the present study reproduce and extend previously reported effects of delay pre-exposure on impulsive choice (Stein et al., 2013), demonstrating both greater LLR choice in DE than IE rats at a 15-s LLR delay, and generalization of this effect to a longer, 30-s LLR delay. Effects of delay pre-exposure were generally robust across time and intervening experience, as differences in choice between DE and IE rats were also observed in the impulsive-choice retest (more than two months following the initial test); however, a significant decline in LLR choice (collapsed across delays) was observed in DE rats between tests.

Rats in the DE group consumed comparable amounts of alcohol as rats in the IE group. Similarly, DE rats consumed comparable amounts of sucrose as IE rats; however, a significant Group×Session Block interaction was observed on sucrose consumption, the source of which appears to be greater initial acceptance of sucrose in DE compared to IE rats in the first two session blocks, with consumption converging between groups by the three latter session blocks.

We observed no evidence of differential early or chronic stress exposure in DE vs. IE rats in the majority of measures in the open-field test (e.g., increased defecation, reduced center exploration; Colorado et al., 2006; Katz et al., 1981). Although DE rats were less active than IE rats, motor activity was unrelated in correlational analyses to either LLR choice or alcohol and sucrose consumption in either DE or IE rats. Thus, between-group differences again appear to be an effect of delay pre-exposure unrelated to stress. These data provide little evidence of a role of stress in the data reported by Stein et al. (2013).

Delay Pre-Exposure and Impulsive Choice

Observed effects of delay pre-exposure on LLR choice were heterogeneous despite significant group differences, as choice in a substantial proportion of DE rats failed to respond to treatment in the impulsive-choice test (approximately one third) and retest (one half). Regarding this heterogeneity, no clear predictors of treatment response were evident in open-field behavior (center entries, motor activity, and defecation) or response latency and trial omissions in the impulsive-choice tests. Total time spent in the food receptacle and the temporal pattern of intra-delay receptacle visits (Cn) in the initial impulsive-choice tests were positively and negatively correlated, respectively, with LLR choice in DE rats. When group levels of these intra-delay behaviors were considered, DE rats spent significantly more time in the receptacle than IE rats during the 30-s (but not 15-s) LLR delay in both impulsive-choice tests. Rats in the DE group also showed greater temporal precision of intra-delay receptacle visits at the 15-s (but not 30-s) LLR delay in the impulsive-choice retest, despite an otherwise inverse relation between Cn and LLR choice within individual groups. Generally, imperfect covariance between group differences in impulsive choice and intra-delay behavior (across delays and tests) indicates that, while these measures may be related, they are to some extent dissociable. Thus, while delay pre-exposure increased time spent in the receptacle and Cn (possible measures of mediating and timing behavior, respectively), neither of these measures likely reflects a primary mechanism underlying observed effects on LLR choice; rather, such changes appear to be ancillary effects of delay pre-exposure.

Despite systematically reproducing and extending the effects of delay pre-exposure on impulsive choice reported by Stein et al. (2013), the present study yielded no evidence of potential mechanism(s) underlying these effects. Because the relation between impulsive choice and LLR delay in psychophysical titration tasks conforms well to hyperbola-like equations in both humans and nonhumans (Mazur, 1987; Rachlin, 1989), it is thought that common behavioral processes underlie choice across species. However, some have recently challenged this notion suggesting species-specific sources of behavioral control (Blanchard, Pearson, & Hayden, 2013; Killeen, 2011). As such, an understanding of the mechanism(s) by which delay pre-exposure exerts its effects should prove useful in elucidating one or more component processes involved in nonhuman impulsive choice. In this section, we consider a number of candidate mechanisms and generate testable predictions for each.

As Killeen (2011) suggested, nonhuman impulsive choice may be a product of differential associability across LLRs and SSRs. That is, intervening delay may weaken memory of the response that produced the LLR, thereby poorly establishing the response-reward association and producing relative SSR preference. In this way, the considerable number of trials during delay pre-exposure (over 11,000 programmed in the present study) may asymptotically strengthen the association between a response and delayed reward, thus increasing LLR choice. Future research may be designed to explore this potential role of associability in delay pre-exposure by examining whether DE rats show faster response acquisition than IE rats during trace conditioning (in which CS and US are temporally distant; e.g., Raybuck & Lattal, 2011).

Delay pre-exposure may also exert its effects on LLR choice by altering timing processes. Although causal relations have yet to be established, prior human and nonhuman data demonstrate an association between impulsive choice and poor performance in timing tasks (e.g., Baumann & Odum, 2012; Marshall, Smith, & Kirkpatrick, 2014; but also see Galtress, Garcia, & Kirkpatrick, 2012). In the abstract, if delay pre-exposure produces changes in the subjective estimation of delay length, then such changes may alter the relative value of LLRs. However, we observed only limited evidence of group differences in our measure of timing (i.e., greater Cn values in DE, compared to IE, rats at the 15-s LLR delay only in the impulsive-choice retest). Moreover, Cn values were negatively related to LLR choice in DE rats—the opposite of what one would predict if timing were a mechanism underlying effects of delay pre-exposure on LLR choice. We note, however, that it is presently unclear how our Cn measure corresponds to validated timing measures more frequently reported in the literature. Future research may be designed to examine the effects of delay pre-exposure on timing speed or precision in peak-interval or temporal bisection task (Catania, 1970).

Finally, in contrast with the accounts described above, a seemingly simple explanation for the present study’s effects on LLR choice may involve habituation to the aversive properties of delay during pre-exposure sessions. Despite this account’s apparent parsimony, however, it is the most ambiguous. Reward delay in operant paradigms can be considered aversive from a behaviorally functional view (Perone, 2003), as delay is a response-contingent stimulus (albeit temporally diffuse) that serves to suppress behavior (e.g., response rate; Jarmolowicz & Lattal, 2013). However, appealing solely to this behaviorally functional definition is inadequate, as a putative role of habituation in delay pre-exposure yields predictions identical to those from all other accounts described above—that is, gradual reductions in response latency during, and elevated LLR choice following, delay pre-exposure. A unique prediction for future research, however, is that a longitudinal assay of the stress hormone, corticosterone, should reveal declining evidence of stress over delay pre-exposure sessions.

The considerations above highlight some of the potential complexities in nonhuman impulsive choice. Identification of functional mechanisms underlying delay pre-exposure’s effects may provide important clues regarding component processes in impulsive choice. In this way, experiential variables like delay pre-exposure may be used as an experimental tool similar to pre-session drug administration in behavioral pharmacology (e.g., use of anxiolytic drugs to examine the role of anxiety in experimental paradigms). We note, however, that the varied behavioral effects of pharmacological treatment (e.g., on the reinforcing efficacy of food, discrimination of reinforcer contingencies, or motor behavior; Chu et al., 2014; Johnson, Stein, Smits, & Madden, 2013; Hoffman & Benninger, 1985) often make it difficult to attribute changes in behavior to precise mechanisms. In the abstract, delay pre-exposure may recruit fewer of these nuisance variables and would therefore be better suited for use in experimentation. However, additional study is required.

Observed heterogeneity in DE rats’ LLR choice in the present study, while suboptimal from a therapeutic view, provides an interesting experimental advantage. Identification of one or more variables (behavioral or biological) that distinguish treatment responders from non-responders in future research may prove important in identifying the mechanism(s) by which delay pre-exposure exerts its effects. With this in mind, one limitation of the present study is that we did not establish baseline levels of impulsive choice prior to delay pre-exposure. In a recent paper, Bickel, Landes, Kurth-Nelson, & Redish (2014) reviewed five prior data sets, finding evidence for rate dependence in treatment effects on impulsive choice. That is, the degree to which impulsive choice responds to treatment variables depends on baseline impulsive choice, with particularly impulsive participants responding the most to treatment and less impulsive participants responding very little or not at all. Given this finding, knowledge of baseline impulsive choice may prove useful in future studies on delay pre-exposure, as a similar (or inverse) form of rate dependence may have been operating in the present data. Ultimately, if the present method is to serve as a valid treatment model for impulsive choice and related substance-use pathology in humans, its phenomenology would ideally resemble that observed in humans.

Finally, one limitation of the present study may be the absence of a true control group, as pre-exposure to immediate (as opposed to delayed) rewards may have served as an independent variable in its own right. That is, exposure to both delayed and immediate rewards may have pushed impulsive choice in opposing directions. We note, however, that impulsive choice in a prior group of experimentally naïve rats in our lab (N = 92; of similar ages, and completing an identical impulsive-choice procedure, as rats in the present study) differed minimally from that observed in IE rats. Thus, pre-exposure to delayed (as opposed to immediate) rewards appears to produce the largest proportion of observed effects on impulsive choice. Nonetheless, we advocate use of an appropriate control group in future research.

Future research should also be designed to examine the effects of delay pre-exposure across varying impulsive-choice tasks (e.g., the adjusting-delay or –amount tasks; Mazur, 1987; Richards, Mitchell, de Wit, & Seiden, 1997). Such investigations would determine whether delay pre-exposure trains tolerance to delayed rewards as a generalized trait, or whether its effects are specific to the increasing-delay task used here. In naïve rats, a recent study in our lab demonstrated within-subject correspondence in naïve rats between measures of impulsive choice in the increasing- and adjusting-delay tasks (rho = .71), although the degree to which these and other tasks may measure ancillary constructs (e.g., sensitivity to reward delay or amount) has yet to be determined.

Delay Pre-Exposure and Alcohol Consumption

Despite significantly reducing impulsive choice in the present study, delay pre-exposure produced no effect on consumption of 12% alcohol. This contrasts with data reported by Stein et al. (2013), in which delay pre-exposure produced significantly greater consumption of 12% alcohol following initial exposure to 3% and 6% alcohol. Because the 12% concentration was introduced alone in the present study (as opposed to gradually), it is possible that the effect of pre-exposure on alcohol consumption reported by Stein et al. depended on gradual introduction of alcohol. In both humans and nonhumans, self-report and electrophysiological data demonstrate that alcohol possesses both sweet and bitter taste components (e.g., Hoopman, Birch, Serghat, Portmann, & Mathlouthi, 1993; Lanier, Hayes, & Duffy, 2005; Lemon et al., 2004; Settle, 1979). Particularly relevant to Stein et al.’s data, alcohol’s sweet component and subjective ratings of pleasantness are more pronounced at low compared to high concentrations, whereas the opposite is true for alcohol’s bitter component (e.g., Hoopman et al., 1993; Scinska et al., 2000). Moreover, sucrose or saccharin preference correlates positively with alcohol consumption across species (e.g., Gosnell & Krahn, 1992; Lush, 1989; Kampov-Polevoy et al., 1995; for review, see Kampov-Polevoy et al., 1999), suggesting common sources of control. That said, we observed no overall group differences in sucrose consumption in the present study. However, we highlight the significant Group×Session Block interaction observed on sucrose consumption, which indicates at least some effect of delay pre-exposure on preference for sweet substances. Whereas we used a relatively high (and perhaps asymptotically rewarding) 21% sucrose concentration in the present study, future research may benefit from employing a lower sucrose concentration (e.g., 6%) that may be more sensitive to group differences in consumption.

Although DE rats were more active in the open-field test than IE rats, motor activity was unrelated to alcohol or sucrose consumption. Together with the absence of group differences in other open-field measures (center entries, defecation), these data suggest a minimal role of stress in Stein et al.’s (2013) prior report of greater alcohol consumption in DE compared to IE rats. However, this conclusion relies on open-field behavior as a proxy measure for prior stress exposure. Future studies may avoid this potential limitation through, as mentioned previously, use of direct measurement of stress hormone, corticosterone.

Beyond the data reported here, recent findings and a closer examination of the literature call into question the robustness of the baseline relation between naturally occurring impulsive choice and alcohol consumption in rodents (i.e., in the absence of delay pre-exposure). The primary evidence for a relation between these variables comes from Poulos et al. (1995), who reported that impulsive choice in outbred rats predicted greater consumption of 12% alcohol. However, subsequent studies failed to find similar predictive relations (Diergaarde, van Mourik, Pattij, Schoffelmeer, & de Vries, 2012; Stein et al., under review). While additional work demonstrated that impulsive choice co-varies with selective breeding for alcohol consumption or seeking (i.e., in a direction similar to that reported by Poulos et al.; Beckwith & Czachowski, 2014; Oberlin & Grahame, 2009; Wilhelm & Mitchell, 2008), the opposite relation has also been reported between these variables (Wilhelm, Reeves, Phillips, & Mitchell, 2007). These inconsistencies diminish the utility of examining alcohol consumption in rodent models when attempting to understand the relation between experimental manipulation of impulsive choice and subsequent drug self-administration. In contrast, the relations between impulsive choice and self-administration of psychostimulant drugs such as cocaine (e.g., Anker, Perry, Gliddon, & Carroll, 2009; Koffarnus & Woods, 2013; Perry et al., 2005; Perry, Nelson, & Carroll, 2008), nicotine (e.g., Diergaarde et al., 2008), or methylphenidate (Marusich & Bardo, 2009), appear to be more consistent than those reported for alcohol. With this in mind, future research may be designed to examine the effects of delay pre-exposure on self-administration of these psychostimulant drugs across a range of experimental phases (e.g., acquisition, maintenance, extinction, and reinstatement).

Conclusions

Together with prior data (Stein et al., 2013), we conclude that that delay pre-exposure reliably reduces impulsive choice and that this effect generalizes to a delay longer than the one used during pre-exposure. In contrast, delay pre-exposure does not reliably affect alcohol consumption. Delay pre-exposure may represent a valuable experimental tool in the study of impulsive choice and drug self-administration, although further investigation is required.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 1R01DA029605 (last author) and the Walter R. Borg Scholarship from the Department of Psychology, Utah State University (first author). All authors thank Tim Shahan and Pat Johnson for assistance in the design of this research, as well as Shayne Barker, Jacy Draper, Brian Hess, and Kennan Liston for assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

Portions of these data were presented at the 2013 and 2014 domestic meetings of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, the 2013 international meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, and the 2013 Behavior Change, Health, and Health Disparities Conference. A report on this research will be submitted by the first author in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

Only rats pre-exposed to fixed delays consumed significantly more alcohol than the comparison group. The difference in alcohol consumption between rats pre-exposed to escalating delays and the comparison group was only marginally significant (p = .07).

Fixed delays were used in the present study because only rats pre-exposed to fixed (and not escalating) delays in Stein et al.’s study showed stable levels of impulsive choice across time, and, as mentioned previously, consumed significantly more alcohol than rats pre-exposed to immediate reward.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey S. Stein, Department of Psychology, Utah State University

C. Renee Renda, Department of Psychology, Utah State University.

Jay E. Hinnenkamp, Department of Psychology, Utah State University

Gregory J. Madden, Department of Psychology, Utah State University

References

- Ainslie G. Specious reward: a behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:463–496. doi: 10.1037/h0076860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Perry JL, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Impulsivity predicts the escalation of cocaine self-administration in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2009;93:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Wileyto EP. Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organizational Research Methods. 2004;7:127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater TL. Effects of stress on alcohol drinking: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:131–156. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Kurth-Nelson Z, Redish AD. Aquantitative signature of self-control repair: rate-dependent effects of successful addiction treatment. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014 doi: 10.1177/2167702614528162. 2167702614528162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Odum AL. Impulsivity, risk taking, and timing. Behavioural processes. 2012;90:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith SW, Czachowski CL. Increased delay discounting tracks with a high ethanol-seeking phenotype and subsequent ethanol seeking but not consumption. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014 doi: 10.1111/acer.12523. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard TC, Pearson JM, Hayden BY. Postreward delays and systematic biases in measures of animal temporal discounting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:15491–15496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310446110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Reinforcement schedules and psychophysical judgements: a study of some temporal properties of behavior. In: Schoenfeld WN, editor. The Theory of Reinforcement Schedules. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1970. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chu SC, Chen PN, Hsieh YS, Yu CH, Meng-Hsuan L, Yan-Han L, Kuo DY. Involvement of hypothalamic PI3K-STAT3 signalling in regulating amphetamine-mediated appetite suppression. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bph.12667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifani C, Polidori C, Melotto S, Ciccocioppo R, Massi M. A preclinical model of binge eating elicited by yo-yo dieting and stressful exposure to food: effect of sibutramine, fluoxetine, topiramate, and midazolam. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:113–125. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1442-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado RA, Shumake J, Conejo NM, Gonzalez-Pardo H, Gonzalez-Lima F. Effects of maternal separation, early handling, and standard facility rearing on orienting and impulsive behavior of adolescent rats. Behavioural processes. 2006;71:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AR, Maxfield AD, Stein JS, Renda CR, Madden GJ. Do the adjusting-delay and increasing-delay tasks measure the same construct: delay discounting? Behavioural Pharmacology. 2014;25:306–315. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diergaarde L, Pattij T, Poortvliet I, Hogenboom F, de Vries W, Schoffelmeer ANM, de Vries TJ. Impulsive choice and impulsive action predict vulnerability to distinct stages of nicotine seeking in rats. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diergaarde L, Van Mourik Y, Pattij T, Schoffelmeer AN, de Vries TJ. Poor impulse control predicts inelastic demand for nicotine but not alcohol in rats. Addiction Biology. 2012;17:576–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, Ryan CN. The pharmacology of impulsive behavior in rats: The effects of drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1996;128:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s002130050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry W, Kelleher RT, Cook L. A mathematical index of performance on fixed-interval schedules of reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1960;3:193–199. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1960.3-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtress T, Garcia A, Kirkpatrick K. Individual differences in impulsive choice and timing in rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2012;98:65–87. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2012.98-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Baldock MD, Locurto C, Gold L, Terrace HS. Trial and intertrial durations in autoshaping. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1977;3:264–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA, Krahn DD. The relationship between saccharin and alcohol intake in rats. Alcohol. 1992;9:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(92)90054-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DC, Beninger RJ. The D1 dopamine receptor antagonist, SCH-23390 reduces locomotor activity and rearing in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1985;22:341–342. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopman T, Birch G, Serghat S, Portmann MO, Mathlouthi M. Solute-solvent interactions and the sweet taste of small carbohydrates. Part II: Sweetness intensity and persistence in ethanol-water mixtures. Food Chemistry. 1993;46:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Lattal KA. Delayed reinforcement and fixed-ratio performance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2013;100:370–395. doi: 10.1002/jeab.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PS, Stein JS, Smits RR, Madden GJ. Pramipexole-induced disruption of behavioral processes fundamental to intertemporal choice. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2013;99:290–317. doi: 10.1002/jeab.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampov-Polevoy AB, Overstreet DH, Rezvani AH, Janowsky DS. Saccharin-induced increase in daily fluid intake as a predictor of voluntary alcohol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1995;57:791–795. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampov-Polevoy AB, Garbutt JC, Janowsky DS. Association between preference for sweets and excessive alcohol intake: a review of animal and human studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34(3):386–395. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz RJ, Roth KA, Carroll BJ. Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: implications for a model of depression. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 1981;5:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(81)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana A, Romer D, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Giannetta JM, Hurt H. Working memory ability predicts trajectories of early alcohol use in adolescents: the mediational role of impulsivity. Addiction. 2013;108:506–515. doi: 10.1111/add.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR. Models of trace decay, eligibility for reinforcement, and delay of reinforcement gradients, from exponential to hyperboloid. Behavioural Processes. 2011;87:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, McCullough ME, Bickel WK, Farley JP, Longo GS. Longitudinal associations among religiousness, delay discounting, and substance use initiation in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jora.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Woods JH. Individual differences in discount rate are associated with demand for self-administered cocaine, but not sucrose. Addiction Biology. 2013;18(1):8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier SA, Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Sweet and bitter tastes of alcoholic beverages mediate alcohol intake in of-age undergraduates. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;83:821–831. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon CH, Brasser SM, Smith DV. Alcohol activates a sucrose-responsive gustatory neural pathway. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:536–544. doi: 10.1152/jn.00097.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSage M, Makhay M, DeLeon I, Poling A. The effects of d-amphetamine and diazepam on schedule-induced defecation in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;48:787–790. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafó MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AT, Smith AP, Kirkpatrick K. Mechanisms of impulsive choice: I. Individual differences in interval timing and reward processing. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2014;102:86–101. doi: 10.1002/jeab.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich JA, Bardo MT. Differences in impulsivity on a delay discounting task predict self-administration of a low unit dose of methylphenidate in rats. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20:447–454. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328330ad6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. Quantitative Analyses of Behavior. 1987;5:55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlin BG, Grahame NJ. High-alcohol preferring mice are more impulsive than low-alcohol preferring mice as measured in the delay discounting task. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:1294–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perone M. Negative effects of positive reinforcement. The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03392064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Carroll ME. The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Larson EB, German JP, Madden GJ, Carroll ME. Impulsivity (delay discounting) as a predictor of acquisition of i.v. cocaine self-administration in female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Impulsive choice as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16:165–177. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos CX, Le AD, Parker JL. Impulsivity predicts individual susceptibility to high levels of alcohol self-administration. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1995;6:810–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Judgment, decision, and choice: A cognitive/behavioral synthesis. WH Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Raybuck JD, Lattal KM. Double dissociation of amygdala and hippocampal contributions to trace and delay fear conditioning. PloS One. 2011;6:e15982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayfield F, Segal M, Goldiamond I. Schedule-induced defecation. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1982;38(1):19–34. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1982.38-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scinska A, Koros E, Habrat B, Kukwa A, Kostowski W, Bienkowski P. Bitter and sweet components of ethanol taste in humans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Tontsch C, Thoeny AL, Kaczkurkin A. Temporal reward discounting in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the contribution of symptom domains, reward magnitude, and session length. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settle RG. The alcoholic's taste perception of alcohol: preliminary findings. Currents in Alcoholism. 1979;5:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Madden GJ. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Addiction Psychopharmacology. 2013. Delay discounting and drug abuse: Empirical, conceptual, and methodological considerations; pp. 165–208. [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Johnson PS, Renda CR, Smits RR, Liston KJ, Shahan TA, Madden GJ. Early and prolonged exposure to reward delay: effects on impulsive choice and alcohol self-administration in male rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21:172–180. doi: 10.1037/a0031245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Renda CR, Barker SM, Liston KJ, Shahan TA, Madden GJ. Impulsive choice predicts anxiety-like behavior, but not alcohol or sucrose self-administration, in male Long-Evans rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. doi: 10.1111/acer.12713. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin R, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Pappas N. Effects of route of administration on cocaine induced dopamine transporter blockade in the human brain. Life Sciences. 2000;67:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6:292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RD, Odum AL. Effects of morphine on temporal discrimination and color matching: General disruption of stimulus control or selective effects on timing? Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2005;84(3):401–415. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.94-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm CJ, Reeves JM, Phillips TJ, Mitchell SH. Mouse lines selected for alcohol consumption differ on certain measures of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1839–1845. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm CJ, Mitchell SH. Rats bred for high alcohol drinking are more sensitive to delayed and probabilistic outcomes. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2008;7:705–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]