Abstract

Objective

Insurance coverage for young adults has increased since 2010, when the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required insurers to permit children on parental policies until age 26 as dependents. This study estimated changes in young adults’ use of hospital-based services with diagnosis codes for mental illness and substance abuse associated with the dependent coverage provision.

Method

Quasi-experimental comparison of national sample of non-birth hospital inpatient admissions to general hospitals (n=2,670,463 total, n=430,583 with primary behavioral health diagnosis) and California emergency department (ED) visits with behavioral health diagnoses (n=11,139,689). Data spanned 2005 to 2011. Estimates compared young adults who were and were not targeted by the ACA dependent coverage provision (19 to 25 versus 26 to 29 year olds), estimating changes in utilization before and after 2010. Primary outcomes included: quarterly inpatient admissions for primary diagnosis of any behavioral health disorder per 1000 population; ED visits with any behavioral health diagnosis per 1000 population; and payer source.

Results

Dependent coverage expansion was associated with 0.14 per 1000 more (p<0.001) inpatient admissions for behavioral health for 19-25 (ACA covered) versus 26-29 (then ACA uncovered) year olds. The coverage expansion was associated with 0.45 fewer behavioral health ED visits per 1000 (p=0.001) in California. The probability that inpatient admissions nationally, and ED visits in California were uninsured, decreased significantly (p<0.001).

Conclusions

ACA dependent coverage provisions produced modest increases in general hospital psychiatric inpatient admissions and higher rates of insurance coverage for young adult children nationally. Lower ED visit rates were observed in California.

Introduction

In 2009, 29% of young adults lacked insurance, exceeding rates for other ages. Because of this historically low insurance rate, coverage is expected to change most for young adults due to the March 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).(1) The first major provision of the ACA, which required insurers to extend dependent coverage eligibility until age 26, took effect in September 2010. Since then, insurance coverage has risen by 3 to 10 percentage points for 19-25 year olds, originating largely from private insurance coverage.(2-5) As the ACA's implementation continues, the major questions shift from tracking uninsurance rates to understanding changes in access to care and health care use. To date, limited evidence on early effects of ACA coverage suggests patients face fewer financial barriers to care, an increase in the share of emergency department (ED) visits covered by private insurance, and no change in the likelihood of having a usual source of care.(5, 6)

Evidence on the relationship between insurance expansions and utilization in hospital settings is mixed.(7-10) Insurance coverage lowers patients’ out-of-pocket costs for hospital-based visits, increasing the likelihood of using care in this setting. On the other hand, insurance may increase access to outpatient services, which could lower rates of potentially preventable ED visits and hospitalizations. Experimental evidence suggests that Oregon's Medicaid expansion increased overall rates of ED use, although ED visits for behavioral health disorders remained stable.(11)

This paper examines young adults’ hospital-based care for behavioral health diagnoses (mental illness and substance use disorders). Behavioral health disorders are the most prominent conditions facing young adults. Most behavioral health disorders emerge by age 24,(12) and mental illness prevalence peaks at ages 18-25.(13) Excluding childbirth, primary diagnoses of behavioral health disorders comprise 16% of inpatient admissions in this age group.(14) Behavioral health conditions have added significance because they often coincide with poor education and employment outcomes.(15-17) Hospital-based care is important for this age group. For example, young adults have high rates of ED use; 1 in 4 18-24 year olds visited an ED in 2010.(18)

The ACA, and its reinforcement of 2008 federal parity law, raises the generosity of coverage for behavioral health care.(19) However, the implications of coverage expansions for young adult utilization of care are poorly understood, and some fear that behavioral health treatment will accelerate cost growth in this age group.(20) One recent study of Massachusetts’ 2006 health reform found that young adults, after experiencing significant insurance coverage gains, had fewer inpatient admissions and ED visits for behavioral health problems compared to other states and age groups.(14) These results may not generalize to the ACA dependent coverage expansion, given more psychiatrists per capita in Massachusetts, and higher hospitalization rates than other US states. In addition, the ACA's extension of private dependent coverage to 19-25 year olds was more limited than Massachusetts’ 2006 reforms, which enacted individual mandates, insurance reforms, and expansions of public and private insurance coverage simultaneously. Using national inpatient discharge data and discharge data on inpatient admissions and ED visits from California, we investigated short-term changes in hospital-based care for behavioral health diagnoses and source of payment for this care among young adults after the dependent coverage expansions.

Data and Measures

We used three data sources from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. To study patterns of inpatient hospitalization, we used the 2005-2011 National Inpatient Samples (NIS), annual random samples of 20% of U.S. community hospitals. Although these data exclude specialty mental health or substance use treatment facilities, the majority of behavioral health inpatient admissions in the U.S. occur in non-specialty community hospitals.(21) Using the NIS sample weights, the data are nationally representative of all inpatient admissions in the sampling frame. We complement the NIS data by studying utilization patterns for all inpatient admissions in California's State Inpatient Database (SID), which includes admissions to specialty mental health or substance use treatment facilities. We studied emergency department (ED) use in California's 2005-2011 State Emergency Department Dataset (SEDD), which includes the universe of ED records in the state. The SEDD excludes ED visits leading to an inpatient admission at the same facility. We confirmed our findings in a sensitivity analysis examining the unduplicated count of total ED visits in California, including inpatient admissions in the SID originating from any ED.

We selected California for analysis because it is the most populous state and because, unlike other large states, its databases of inpatient and ED discharges, including specialty mental health and substance use facilities, were available throughout the study period. Finally, insurance coverage for young adult Californians grew substantially after implementation of the ACA's dependent coverage provision.(4) California's discharge data employ selected age-masking to protect patient confidentiality, which could bias estimated changes in hospital-based service use toward zero. We discuss the methods and scope of age-masking, and its likely limited impact for our analysis in the Supplemental Methods section.

Primary outcomes included rates of non-birth, behavioral health inpatient admissions and ED visits. For inpatient hospitalizations, we considered admissions with a primary diagnosis of any behavioral health disorder at discharge (ICD-9 codes 296.xx-319.xx), stratifying analyses for primary diagnoses of depression, psychoses/schizophrenia, substance use disorders, and all other behavioral health diagnoses as described in Supplemental Table 1.

The SEDD data do not distinguish primary from other diagnoses, so we studied visits with any behavioral health diagnosis associated with the visit. We created mutually exclusive categories: depression only, psychosis only, substance use disorder only, substance use disorder and any mental illness, more than one mental illness, and all other behavioral health (Supplemental Table 1), where “only” indicates the absence of other behavioral health diagnoses for that visit.

The 2005-2011 NIS data include 2,670,463 non-birth admissions, of which 430,583 had a primary behavioral health diagnosis. After applying the NIS sampling weights, those observations represent 2,136,503 admissions with a primary behavioral health diagnosis nationally, or 16% of all non-childbirth admissions. The 2005-2011 California SID data include 1,265,314 non-childbirth-related inpatient admissions, 254,664 (20%) of which had a primary behavioral health diagnosis. The 2005-2011 California SEDD data include 11,139,689 non-childbirth-related ED visits, 1,577,850 (14%) of which had any behavioral health diagnosis. We also examined the expected primary payer of each inpatient admission and ED visit, to assess whether the likelihood that services were uninsured, or were covered by private insurance, changed after the dependent coverage expansion.

We measured inpatient hospitalizations and ED visits as rates per 1000 population, following methods used to study effects of prior insurance expansions.(14, 22) We created 616 “cells” defined by single year of age (19-29), sex, and quarter (2005 through 2011). In each cell, numerators reflect total admissions for that age-sex-quarter group. The denominators are the Census bureau's national and state-level population estimates corresponding to the numerators from the NIS, SID, and SEDD.(23)

Statistical Analysis

We used a difference-in-differences research design, estimating differential changes in hospital-based service use among young adults with behavioral health diagnoses before and after the dependent coverage expansions. We compared changes for ages targeted by the provision, 19-25 year olds, relative to an otherwise similar group in terms of levels and trends in service use but not targeted by dependent coverage changes, 26-29 year olds.

Although the dependent coverage provision went into effect September 23, 2010, a number of large insurers extended dependent coverage through age 25 before the formal implementation date to prevent gaps in coverage for new graduates.(24) Previous work documented significant increases in parental employer-sponsored insurance coverage during this interim period, although these increases appear to reflect shifting from sources of insurance for young adults, and rates of insurance coverage remained unchanged.(2) Due to this complex transition, we defined the second and third quarters of 2010 as the “interim” expansion period, and we defined the fourth quarter of 2010 and later as the post-dependent coverage expansion period.

For each outcome, we estimated the following linear regression model:

where Yikt=admissions or visits per 1000 population for age i, sex k, and quarter t. The term agei represents a set of 10 indicator variables for each individual year of age. Quartert is a set of 27 indicator variables for each quarter (excluding the first), which control for secular trends and seasonality in the outcome. We created an interaction term between the variables “interim” (=1 April through September 2010, and 0 otherwise) and “age 19 to 25i” (=1 for age 19-25 rates, and 0 otherwise). We created a second interaction between “aftert” (=1 after September 2010, and 0 otherwise) and “age 19 to 25i”. The coefficient β1 is interpreted as the differential change in inpatient or ED use between treatment and control groups during the interim implementation period of the dependent coverage expansion, and the coefficient β2 yields the differential change in inpatient or ED use between the treatment and control group after the dependent coverage expansion went into effect. The inclusion of the full set of indicator variables for single year of age and quarter obviates the need to include main effects for the “age 19-25,” “interim,” and “after” variables. We estimated additional models stratified by gender, due to known gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of specific behavioral health disorders, and in initiation and course of treatment.(25-28) We estimated our regression models with robust Huber-White standard errors, and we report p-values based on two-tailed t-statistics.

Consent was waived for our study of secondary data, reviewed and deemed exempt by Dartmouth College's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Results

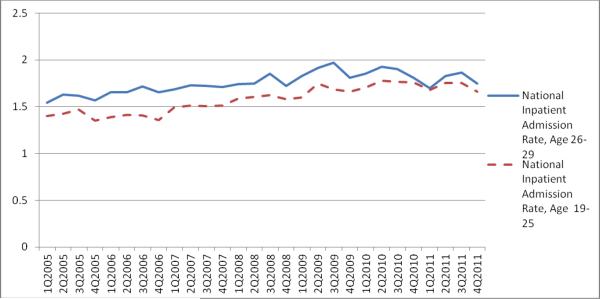

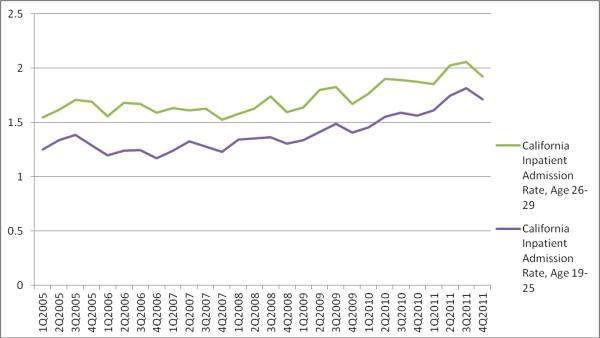

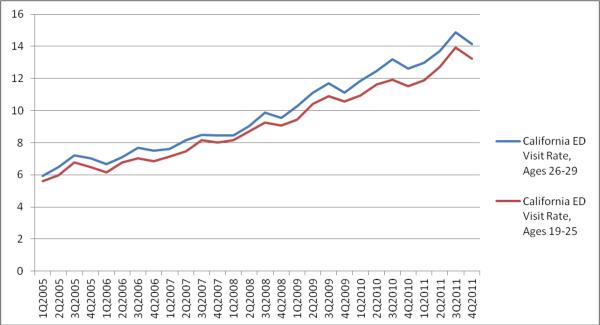

Use of hospital-based services increased over the study period (Figure 1). Importantly, trends in outcomes were similar between the two age groups before the dependent coverage expansion, validating the difference-in-differences research design. The national quarterly inpatient hospitalization rate at non-specialty hospitals during the study period was 1.58/1000 for 19-25 year olds and 1.75/1000 for 26-29 year olds, with slightly lower rates comparing females to males. In California, the average quarterly inpatient admission rate was 1.40/1000 for 19-25 year olds and 1.72/1000 for 26-29 year olds, while the average quarterly ED visit rate was 9.17/1000 and 9.83/1000 for 19-25 and 26-29 year olds, respectively (Table 1). The trends in the pre-period ED visit rates were similar across age groups, just as they were for inpatient admissions, validating our choice of comparison group (see Supplemental Methods section for statistical evidence that trends were parallel). Behavioral health diagnoses were common; 16% of non-birth inpatient admissions to community hospitals nationally, 20% of non-birth inpatient admissions in California for 19-25 year olds had a primary behavioral health diagnosis, and 14% of ED visits in California for 19-25 year olds involved a behavioral health diagnosis.

Figure 1. Behavioral Health Inpatient and Emergency Department Use Rates, 2005-2011.

Panel A. National Inpatient Admissions to non-Specialty Behavioral Health Facilities, with Primary Behavioral Health Diagnosis per 1000 population, 2005-2011

Panel B. California Inpatient Admissions with Primary Behavioral Health Diagnosis per 1000 population, 2005-2011

Panel C. California Emergency Department Visits with Any Behavioral Health Diagnosis per 1000 population, 2005-2011

Table 1.

Characteristics of Behavioral Health Inpatient Admissions & Emergency Department Visits, 2005-2011

| 19-25 year olds | 26-29 year olds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Males | Females | Full Sample | Males | Females | |

| Panel A. National Inpatient Admission Rates per 1000 Population (SD) | ||||||

| Primary diagnosis of: | ||||||

| Any mental illness or SUDa | 1.58 (0.23) | 1.69 (0.23) | 1.47 (0.17) | 1.75 (0.22) | 1.89 (0.18) | 1.62 (0.16) |

| Depression | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.24 (0.04) | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.31 (0.06) | 0.26 (0.03) | 0.36 (0.04) |

| Psychoses | 0.52 (0.16) | 0.65 (0.12) | 0.39 (0.07) | 0.61 (0.17) | 0.75 (0.11) | 0.47 (0.07) |

| Substance Use Disorder | 0.27 (0.09) | 0.34 (0.07) | 0.21 (0.05) | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.45 (0.05) | 0.25 (0.04) |

| Other Mental Illness | 0.49 (0.07) | 0.45 (0.07) | 0.52 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.08) | 0.43 (0.05) | 0.54 (0.06) |

| Length of Stay | 6.44 (0.65) | 6.92 (0.49) | 5.97 (0.40) | 6.58 (0.57) | 6.96 (0.46) | 6.20 (0.40) |

| # age and sex-specific quarterly rates | 392 | 196 | 196 | 224 | 112 | 112 |

| # inpatient admissions (weighted) | 1,329,051 | 725,755 | 603,296 | 807,452 | 436,505 | 370,947 |

| Panel B. California Inpatient Admission Rates per 1000 Population (SD) | ||||||

| Primary diagnosis of: | ||||||

| Any mental illness or SUD | 1.40 (1.28) | 1.58 (1.49) | 1.23 (1.00) | 1.72 (1.49) | 1.95 (1.74) | 1.49 (1.15) |

| Depression | 0.21 (0.20) | 0.18 (0.17) | 0.25 (0.22) | 0.24 (0.20) | 0.20 (0.17) | 0.28 (0.22) |

| Psychoses | 0.62 (0.64) | 0.82 (0.79) | 0.42 (0.35) | 0.85 (0.82) | 1.12 (1.00) | 0.58 (0.46) |

| Substance Use Disorder | 0.18 (0.18) | 0.23 (0.22) | 0.12 (0.11) | 0.21 (0.20) | 0.26 (0.24) | 0.15 (0.12) |

| Other Mental Illness | 0.39 (0.33) | 0.35 (0.32) | 0.43 (0.34) | 0.43 (0.36) | 0.38 (0.34) | 0.47 (0.37) |

| Length of Stay | 6.93 (0.89) | 7.37 (0.83) | 6.48 (0.71) | 7.14 (0.85) | 7.49 (0.76) | 6.78 (0.78) |

| # age and sex-specific quarterly rates | 392 | 196 | 196 | 224 | 112 | 112 |

| # inpatient admissions | 150,010 | 87,699 | 62,311 | 104,654 | 60,555 | 44,3099 |

| Panel C. California EDa Visit Rates per 1000 Population (SD) | ||||||

| Visit with any diagnosis of: | ||||||

| Any mental illness or SUD diagnosis | 9.17 (3.03) | 9.14 (3.15) | 9.20 (2.90) | 9.83 (3.32) | 9.89 (3.43) | 9.77 (3.23) |

| Depression diagnosis (only) | 0.51 (0.25) | 0.32 (0.11) | 0.69 (0.21) | 0.56 (0.30) | 0.35 (0.12) | 0.78 (0.26) |

| Psychoses diagnosis (only) | 0.63 (0.23) | 0.73 (0.23) | 0.54 (0.18) | 0.77 (0.27) | 0.89 (0.28) | 0.66 (0.21) |

| SUD diagnosis (only) | 4.83 (1.82) | 5.30 (1.95) | 4.36 (1.54) | 4.98 (1.96) | 5.63 (2.06) | 4.33 (1.62) |

| 2 or more mental disorder diagnoses | 0.29 (0.11) | 0.24 (0.08) | 0.34 (0.10) | 0.32 (0.13) | 0.26 (0.09) | 0.39 (0.13) |

| Co-occurring SUD and mental diagnoses | 0.88 (0.37) | 0.95 (0.39) | 0.82 (0.33) | 1.00 (0.42) | 1.06 (0.42) | 0.93 (0.41) |

| Other behavioral health diagnoses | 2.03 (0.73) | 1.60 (0.50) | 2.46 (0.66) | 2.19 (0.83) | 1.70 (0.57) | 2.68 (0.75) |

| # age and sex-specific quarterly rates | 392 | 196 | 196 | 224 | 112 | 108 |

| # ED visits | 982,167 | 510,086 | 472,081 | 595,683 | 306,825 | 288,858 |

SUD, substance use disorder; ED, emergency department

b – Individuals with “Depression(only)” “Psychoses (only)” or SUD (only) indicates no other mental illness or substance use disorder diagnosis. Other physical diagnoses may be present on these discharge records.

Behavioral health inpatient admissions to non-specialty hospitals increased more for 19-25 year olds compared with 26-29 year olds after the dependent coverage provision (0.14 per 1000, p<0.001; Table 2). The differential rise in inpatient admissions was smaller during the interim implementation period, and did not reach statistical significance (β1= 0.06, p=0.063). The dependent coverage expansion was associated with significant increases in inpatient admission rates for all of the specific primary behavioral health diagnoses (Supplemental Table 2). After stratifying by sex, the increases in inpatient admissions were positive and statistically significant for both males and females. However, the increase was significantly larger for males. Inpatient admissions also differentially rose for males during the interim implementation period, (β1= 0.10, p=0.008). Significant increases for males were found within each specific behavioral health category, but only depression and psychoses admissions increased significantly more among females comparing 19-25 year olds with 26-29 year olds (Supplemental Table 2). In the California inpatient data, estimates were similar to the national data, with smaller estimated effects and wider confidence intervals. Inpatient admission rates did not significantly increase overall or for females. However, among males, admissions grew 0.12 per 1000 more for 19-25 versus 26-29 year olds (p=0.011). Among the specific behavioral health categories in the full California sample, only admission rates for SUD and for other mental illness increased significantly (Supplemental Table 3). Both increases were significant for males, whereas only the increase in SUD admissions was significant for females (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 2.

Differential Change in Inpatient Admissions and ED Visits with Behavioral Health Diagnoses per 1000 for 19-25 Year Olds After Implementation of Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Provision

| Full Sample (n = 616 age and sex-specific quarterly admission rates) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interim expansion period, age 19-25 vs. 26-29 | (95% CI) | P-value | Post-expansion period, age 19-25 vs. 26-29 | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Outcome | ||||||

| National Inpatient Admissions | 0.06 | (−0.003,0.13) | 0.063 | 0.14 | (0.10,0.17) | <0.001 |

| California Inpatient Admissions | 0.01 | (−0.19,0.22) | 0.911 | 0.08 | (−0.06,0.22) | 0.282 |

| California EDb Visits | −0.51 | (−0.76,−0.25) | <0.001 | −0.45 | (−0.72,−0.19) | 0.001 |

| Males (n = 308 age-specific quarterly admission rates) | ||||||

| National Inpatient Admissions | 0.10 | (0.03,0.18) | 0.008 | 0.20 | (0.15,0.26) | <0.001 |

| California Inpatient Admissions | 0.0001 | (−0.09,0.09) | 0.998 | 0.12 | (0.03,0.21) | 0.011 |

| California EDb Visits | −0.32 | (−0.65,0.02) | 0.063 | −0.09 | (−0.37,0.20) | 0.544 |

| Females (n = 308 age-specific quarterly admission rates) | ||||||

| National Inpatient Admissions | 0.02 | (−0.05,0.10) | 0.515 | 0.07 | (0.02,0.11) | 0.004 |

| California Inpatient Admissions | 0.02 | (−0.05,0.10) | 0.560 | 0.04 | (−0.04,0.13) | 0.340 |

| California EDb Visits | −0.69 | (−1.02,−0.37) | <0.001 | −0.81 | (−1.12,−0.50) | <0.001 |

a –Table shows coefficient estimate on age 19-25 quarterly admission/visit rates interacted with indicator for interim expansion period (2nd and 3rd quarters 2010) and post period (4th quarter 2010-2011) in regression models of admission/visit rates controlling for age, quarter, and (where appropriate) sex. 95% confidence intervals are based on robust Huber-White standard errors, and p-values are based on two-tailed t-statistics.

ED, emergency department

In contrast to the inpatient results, the dependent coverage expansion was associated with significantly slower growth in the rates of ED use with any behavioral health diagnosis. In California, growth in ED visits not leading to inpatient admission was 0.45 per 1000 (p<0.001) lower among 19-25 year olds compared with 26-29 year olds after the coverage expansion (Table 2). The differential reduction in ED use was observed in the interim implementation period as well (β1= −0.51, p<0.001). Stratifying by sex, the slower growth in ED visits with behavioral health diagnoses after the coverage expansion was significant for females (β2=−0.81; p<0.001) but not for males (β2=−0.09; p=0.544). The difference in trends of ED use significantly dropped during the interim implementation period for females (β1= -0.69, p<0.001), but not for males (β1= −0.32, p=0.063). We found significantly slower growth in ED visits within all diagnostic categories except “other behavioral health” (Supplemental Table 4). Mirroring the results for all ED visits with behavioral health diagnoses, the slower growth in visits for specific diagnoses were significant, except for “other behavioral health” visits, among females. For males, only the reduction in psychoses-related ED visits was significant, and rates of ED visits with a diagnosis of “other behavioral health” increased faster among 19-25 year olds compared with 26-29 year olds (0.11; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.19). Sensitivity analyses estimating trends in rates of ED visits, including visits resulting in admissions at the same facility, yielded virtually identical results (Supplemental Table 5).

After the dependent coverage expansion, the probability that inpatient admissions and ED visits for behavioral health were uninsured decreased (Table 3). The probability that inpatient admissions were uninsured fell 2.9 percentage points nationally comparing 19-25 with 26-29 year olds after dependent coverage expansions (p<0.001), and by 2.8 percentage points in California (p<0.001). The probability of uninsured ED visits in California dropped by 3.9 percentage points (p<0.001). Stratifying by sex, estimated reductions in uninsured discharges were statistically significant, though larger in magnitude for males than females. The likelihood that hospital-based care was uninsured did not significantly change during the interim implementation period. However, the share of hospital-based care that was covered by private insurance increased significantly both in the interim implementation period, and in the post-coverage expansion period (Supplemental Table 6).

Table 3.

Differential Change in Likelihood that Inpatient Admissions and ED Visits with Behavioral Health Diagnoses for 19-25 Year Olds are not covered by Insurance, After Implementation of Dependent Coverage Provision

| Full Sample (n = 616 age and sex-specific quarterly admission rates) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interim expansion period, age 19-25 vs. 26-29 | (95% CI) | P-value | Post-expansion period, age 19-25 vs. 26-29 | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Outcome | ||||||

| National Inpatient Admissions | −0.003 | (−0.01,0.01) | 0.567 | −0.029 | (−0.04,−0.02) | <0.001 |

| California Inpatient Admissions | 0.002 | (−0.01,0.02) | 0.781 | −0.028 | (−0.04,−0.02) | <0.001 |

| California EDb Visits | −0.006 | (−0.02,0.01) | 0.342 | −0.039 | (−0.05,−0.03) | <0.001 |

| Males (n = 308 age-specific quarterly admission rates) | ||||||

| National Inpatient Admissions | 0.002 | (−0.02,0.02) | 0.818 | −0.035 | (−0.05,−0.02) | <0.001 |

| California Inpatient Admissions | 0.008 | (−0.01,0.03) | 0.412 | −0.032 | (−0.05,−0.02) | <0.001 |

| California EDb Visits | −0.006 | (−0.02,0.01) | 0.352 | −0.045 | (−0.06,−0.03) | <0.001 |

| Females (n = 308 age-specific quarterly admission rates) | ||||||

| National Inpatient Admissions | −0.008 | (−0.02,0.002) | 0.118 | −0.023 | (−0.03,−0.01) | <0.001 |

| California Inpatient Admissions | −0.004 | (−0.02,0.01) | 0.659 | −0.023 | (−0.04,−0.01) | <0.001 |

| California EDb Visits | −0.005 | (−0.02,0.01) | 0.342 | −0.033. | (−0.04,−0.03) | <0.001 |

a –Table shows coefficient estimate on age 19-25 quarterly admission/visit rates interacted with indicator for interim expansion period (2nd and 3rd quarters 2010) and post period (4th quarter 2010-2011) in regression models of share of admissions/visits that were uninsured, controlling for age, quarter, and (where appropriate) sex. 95% confidence intervals are based on robust Huber-White standard errors, and p-values are based on two-tailed t-statistics.

ED, emergency department

Discussion

After the ACA's expansion of dependent coverage until age 26, use of inpatient behavioral health care in non-specialty hospitals rose modestly faster for young adults targeted by the expansion compared to those just above the age cutoff. These increases were stronger for males, led by growth in admissions for psychosis and substance use disorder. The picture from emergency departments in California differs. Dependent coverage expansions coincided with slightly smaller increases in rates of ED visits with behavioral health diagnoses among young adults, compared with 26-29 year olds. Following the dependent coverage expansions in the ACA, both inpatient and ED services with behavioral health diagnoses for young adults were less likely to be uninsured, consistent with early evidence on ED use for emergent conditions by Mulcahy and colleagues.(6) The likelihood that hospital-based care for behavioral health diagnoses was covered by private insurance also rose. This rise started immediately after enactment of the ACA and increased after the dependent coverage expansion was fully implemented, consistent with evidence by Akosa Antwi and colleagues.(2) That the increase in private insurance preceded declines in uninsurance may suggest that early adopters of dependent coverage moved from government-sponsored coverage, though we cannot rule out other explanations.

Rates of inpatient admissions for behavioral health increased 8.4% relative to the pre-expansion rates. Our results, combined with the Census Bureau's 2010 estimate of 29.7 million Americans age 19-25, imply an increase of 16,632 behavioral health inpatient admissions per year. To put these findings in perspective, the existing research using data through 2011 finds that the proportion of 19-25 year olds with insurance increased by between 4.8% and 6.9% relative to levels of coverage before the dependent coverage expansion, with over three million gaining coverage by the end of 2011.(2, 4, 5, 29) In addition, many more young adults responded to the ACA's dependent coverage expansion by switching from individually-purchased or employer-sponsored plans in their own names to parental plans.(2, 30) It is plausible that these young adults received more comprehensive and generous coverage under parental policies. Increased insurance could lead to more clinically appropriate hospitalizations if necessary services became more affordable because of expanded insurance, or if greater access to outpatient services identified the need for hospitalization. To the extent that this happened, additional hospitalizations, though cost increasing, would coincide with good clinical care. Changes in ED visits after the ACA suggest beneficial effects of the dependent coverage expansion. In California, ED visits with behavioral health diagnoses were 4.9% lower relative to the pre-dependent coverage expansion rates of ED use. Based on the size of the 19-25 year old population in 2010 in California,(23) our results imply that the number of annual ED visits with behavioral health diagnoses dropped by 7,044 in a large and diverse state with low levels of insurance coverage relative to national averages. One possible explanation for this result is that improved access to outpatient behavioral health care more than offset any increased incentives to use the ED because of expanded private insurance coverage. We find that the reductions in ED use started immediately after the ACA's enactment, and that the proportion of visits covered by private insurance also started to rise during the six-month interim implementation period. Understanding how patterns of outpatient behavioral health service use change in response to the ACA's insurance expansions is a priority for future research. However, this result may also reflect the possibility that the insurance coverage which was gained following the dependent coverage expansion relied on managed behavioral health techniques (such as 24-hour nurse triage lines) to facilitate the use of less-expensive outpatient settings and minimize more expensive treatment modalities such as EDs.(31)

Our inpatient results mirror findings describing inpatient admissions for mental illness,(10) but no evidence to date captures differences by sex, ED visits, nor does this work capture care in specialty mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities, as we do using California discharge data. In contrast to the recent experimental Oregon Health Study, which found overall increases in ED use, though no increases for behavioral health-related ED use, we find declines for ED visits with behavioral health diagnoses.(11) The discrepancy may reflect two key differences between their study and ours. The Medicaid-eligible population in Oregon has lower income, and was older than our study population. Also, Medicaid coverage could affect ED use very differently than private insurance studied here. Associations between the dependent coverage expansion and hospital-based care differed by sex. Insurance gains after the ACA were higher for males than females, although differences were modest.(4, 5) Inpatient admission growth was greater for males than for females, while declines in ED use were concentrated among females. One possible explanation is that females took greater advantage of increased insurance to use effective outpatient behavioral health services that reduced the need for hospital-based care. This represents an important avenue for future investigation.

Although we use a strong quasi-experimental design, our study has some limitations. First, discharge data lack clinical information to determine whether higher admission rates reflect clinically-appropriate, cost-effective services or services of marginal efficacy. Second, because we do not observe outpatient treatment, we cannot determine whether findings are due to the provision of more effective or frequent outpatient treatments, changes in the underlying health of the population, or restrictions on ED visits under managed care contracts. These gaps in knowledge underscore the importance of comprehensive data across care settings to understand the ACA's effects.

Third, the NIS data exclude admissions to specialty psychiatric or substance use-treatment facilities. However, only 58% of total inpatient mental health spending and 71% of total inpatient substance abuse spending nationwide occurs in non-specialty hospitals.(21) In addition, we complemented the NIS data with SID data from California which did include specialty behavioral health facilities and the results were similar. However, the SID results do not achieve the level of statistical significance seen in the NIS, due to a smaller sample and the aforementioned age-masking, which could shrink the magnitude of our estimate since some adults have randomly misclassified ages. Finally, we only consider the first 15 months of ACA implementation and thus cannot describe medium-run or long-run trends in hospital-based care.

As the ACA expands insurance to millions of Americans, it is crucial to understand the effects of new coverage on patterns of care and spending. For young adults, a group with significant behavioral health needs, and a group likely to experience large gains in coverage due to the ACA, inpatient behavioral health care rose, ED use for behavioral health fell, and the proportion of hospital-based services that were uninsured dropped after the dependent coverage expansion. Future research will assess whether these patterns will hold as the ACA expands insurance more broadly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding sources:

We gratefully acknowledge funding from NIDA grants R01 DA030391, R01 DA026414, and K24 DA019855. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Golberstein had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All analyses were completed by Ms. Zaha, Dr. Golberstein, and Dr. Meara.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

None of the authors of this manuscript report any competing interests.

Contributor Information

Ezra Golberstein, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Susan H. Busch, Department of Health Policy and Management Yale School of Public Health susan.busch@yale.edu.

Rebecca Zaha, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice Geisel School of Medicine rebecca.zaha@dartmouth.edu.

Shelly F. Greenfield, Harvard Medical School sgreenfield@mclean.harvard.edu.

William R. Beardslee, Baer Prevention Initiatives, Department of Psychiatry Boston Children's Hospital AND Gardner-Monks Professor of Child Psychiatry Harvard Medical School william.beardslee@childrens.harvard.edu.

Ellen Meara, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice Geisel School of Medicine AND National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA ellen.r.meara@dartmouth.edu.

References

- 1.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011. U.S. Census Bureau. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akosa Antwi Y, Moriya AS, Simon K. Effect of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act's Dependent Coverage Mandate. Am Econ J-Econ Polic. 2012;5(4):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantor JC, Monheit AC, DeLia D, Lloyd K. Early impact of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage of young adults. Health Serv Res. 2012 Oct;47(5):1773–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Hara B, Brault MW. The Disparate Impact of the ACA-Dependent Expansion across Population Subgroups. Health Serv Res. 2013 Oct;48(5):1581–92. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommers BD, Buchmueller T, Decker SL, Carey C, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act has led to significant gains in health insurance and access to care for young adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Jan;32(1):165–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulcahy A, Harris K, Finegold K, Kellermann A, Edelman L, Sommers BD. Insurance coverage of emergency care for young adults under health reform. N Engl J Med. 2013 May 30;368(22):2105–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year. Q J Econ. 2012 Aug;127(3):1057–106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson M, Dobkin C, Gross T. The Effect of Health Insurance on Emergency Department Visits: Evidence from an Age-Based Eligibility Threshold. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013 Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson M, Dobkin C, Gross T. The Effect of Health Insurance Coverage on the Use of Medical Services. Am Econ J-Econ Polic. 2012 Feb;4(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akosa Antwi Y, Moriya AS, Simon K. Access to Health Insurance and the Use of Inpatient Medical Care: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Mandate. NBER Working Paper 20202. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, Baicker K, Finkelstein AN. Medicaid Increases Emergency-Department Use: Evidence from Oregon's Health Insurance Experiment. Science. 2014 Jan 17;343(6168):263–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1246183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2012. Contract No.: NSDUH Series H-42, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4667. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meara E, Golberstein E, Zaha R, Greenfield SF, Beardslee WR, Busch SH. Use of Hospital-based Services among Young Adults with Behavioral Health Diagnoses Before and After Health Insurance Expansions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3972. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ettner SL, Frank RG, Kessler RC. The impact of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 1997 Oct;51(1):64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berndt ER, Koran LM, Finkelstein SN, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, Miller IM, et al. Lost human capital from early-onset chronic depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 Jun;157(6):940–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullahy J, Sindelar JL. Drinking, Problem Drinking, and Productivity. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 347–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States, 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care. Hyattsville, MD: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Substantial Improvements to Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Coverage in Response to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy K. Mental health bills may limit young Americans’ clout. USA Today. 2013 Nov 6; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1986-2009. Rockville, MD: 2013. Contract No.: HHS Publication No. SMA-13-4740. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller S. The effect of insurance on emergency room visits: An analysis of the 2006 Massachusetts health reform. J Public Econ. 2012 Dec;96(11-12):893–908. [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Census Bureau Intercensal Population Estimates. 2013 Oct 28; Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal.

- 24.U.S. Department of Labor Fact Sheet: Young Adults and the Affordable Care Act: Protecting Young Adults and Eliminating Burdens on Families and Businesses [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenfield SF, Rosa C, Putnins SI, Green CA, Brooks AJ, Calsyn DA, et al. Gender research in the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Treatment Clinical Trials Network: a summary of findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011 Sep;37(5):301–12. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IOM (Insitute of Medicine) and NRC (National Research Council) Improving the Health, Safety, and Well-Being of Young Adults: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, Neill Epperson C. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014 Jun 2; doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Jan 5;86(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sommers BD. Number of Young Adults Gaining Insurance Due to the Affordable Care Act Now Tops 3 Million. 2012 Jun 19; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sommers BD, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage for young adults. JAMA. 2012 Mar 7;307(9):913–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.307.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank RG, Garfield RL. Managed Behavioral Health Care Carve-Outs: Past Performance and Future Prospects. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:303–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.