Abstract

Neuropsychological dysfunction is associated with risk for suicidal behavior, but it is unknown if antidepressant medication treatment is effective in reducing this dysfunction, or if specific medications might be more beneficial. A comprehensive neuropsychological battery was administered at baseline and after eight weeks of treatment within a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comparing paroxetine and bupropion in study of patients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder and either past suicide attempt or current suicidal thoughts. Change in neurocognitive performance was compared between assessments and between medication groups. Treatment effects on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Scale for Suicidal Ideation were compared with neurocognitive improvement. Neurocognitive functioning improved after treatment in all patients, without clear advantage for either medication. Improvement in memory performance was associated with a reduction in suicidal ideation independent of the improvement of depression severity. Overall, antidepressant medication improved neurocognitive performance in patients with major depression and suicide risk. Reduced suicidal ideation was best predicted by a combination of the independent improvements in both depression symptomatology and verbal memory. Targeted treatment of neurocognitive dysfunction in these patients may augment standard medication treatment for reducing suicidal behavior risk.

Keywords: Major Depression, Suicide, Antidepressant Treatment, Cognition

1. Introduction

Neurocognitive deficits are a risk factor for suicidal behavior. Impaired neurocognitive functioning has been found in patients with histories of suicide attempt (King et al., 2000; Keilp et al., 2001; Keilp et al., 2008; Dombrovski et al., 2008; Jollant et al., 2011; Keilp et al., 2013) and those with current suicidal ideation (Marzuk et al., 2005; Westheide et al., 2008). These impairments extend beyond the neurocognitive problems associated with depression. Poorer performance on tests of attention, memory and language fluency are most consistently reported in depressed suicide attempter samples (Keilp et al., 2013; Jollant et al., 2011; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2014a; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2014b). Antidepressant treatment can improve neurocognitive performance in patients with major depression (Constant et al., 2005; Gallassi et al., 2006; Herrera-Guzman et al., 2008; Herrera-Guzman et al., 2009), but it is unknown if it is effective in reducing neurocognitive deficits that are specifically related to the risk for suicidal behavior.

Patients with suicidal ideation and past suicidal behavior are typically excluded from antidepressant clinical trials due to safety concerns, limiting the data available to inform treatment selection in this population. In the only known randomized, double-blind study of patients specifically selected for elevated suicide risk, Grunebaum et al. (2012) found a relative advantage for paroxetine in comparison to bupropion in reducing suicidal ideation in patients with the most severe levels of ideation at baseline. Compared with bupropion, paroxetine treatment also produced greater reduction in depressive symptoms in patients with greater initial depression severity.

However, no study has yet examined whether there are differential treatment benefits among antidepressant medications in terms of reducing neurocognitive dysfunction in patients at risk for suicide. Treatment of suicidal patients has typically focused on reducing depressive symptoms believed to be the principal determinant underlying suicidal behavior (Henriksson et al., 1993). Evidence that treatment-related improvements in neurocognitive functioning are partially independent from improvement in the clinical symptoms of MDD (Herrera-Guzman et al., 2009), though, suggests that neurocognitive difficulties should be considered a distinct and essential target of treatment. Persistent neurocognitive problems in the context of improved mood state (Fava et al., 2006; Majer et al., 2004; Paelecke-Habermann et al., 2005) are also associated with poor psychosocial functioning (Murrough et al., 2011; Jaeger et al., 2006) that can prolong distress and extend the period of suicide risk. Medications that enhance cognition in conjunction with relieving depressive symptoms may then offer better treatment outcomes for patients at high risk for suicidal behavior.

Antidepressant medications augment the activity of monoamine systems that modulate both mood and cognition (Booij et al., 2003). Drugs that specifically increase available levels of norepinephrine and dopamine, such as bupropion, a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), may be particularly advantageous for producing neurocognitive change. Improved neurocognitive functioning in response to antidepressants with noradrenergic effects has been reported (Gallassi et al., 2006) with neurocognitive gains exceeding those associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment in depressed patients (Ferguson et al., 2003; Herrera-Guzman et al., 2009; Herrera-Guzman et al., 2010). Bupropion has demonstrated efficacy in adult patients with ADHD (Wilens et al., 2005; Banaschewski, 2004). It has also been shown to improve verbal memory and processing speed in children with ADHD (Clay et al., 1988) with specific benefits to performance of learning, attention and memory tasks relative to methylphenidate (Barrickman et al., 1995). Within depressed patients, improvements in visual memory and processing speed were seen after an eight-week trial of bupropion (Herrera-Guzman et al., 2008). Gualtieri and Johnson (2007) found that MDD patients treated with bupropion had neuropsychological functioning comparable to that of non-depressed comparison subjects, while patients taking SSRIs continued to exhibit impairments in psychomotor speed and neurocognitive flexibility.

We administered a comprehensive set of neuropsychological measures in the high suicide-risk patient sample of Grunebaum et al. (2012) before and after eight weeks of randomized antidepressant treatment with either an SSRI (paroxetine) or an NDRI (bupropion). The current study had three main objectives. First, to determine whether neurocognitive performance can be improved with antidepressant treatment specifically within high-risk individuals. Second, to investigate whether antidepressant medications with disparate mechanisms of action have differential effects on neurocognitive functioning in a high-risk sample. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that bupropion would produce greater improvement in overall neurocognitive performance and that paroxetine would produce greater improvement in specific measures of impulsivity. Third, we examined the relationship between treatment-related changes in neurocognitive performance and measures of clinical improvement related to suicidal behavior risk (severity of depression and suicidal ideation).

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Detailed study methods have been reported elsewhere (Grunebaum et al., 2012). Subjects were adults meeting DSM-IV criteria for current unipolar Major Depressive Disorder. All subjects had a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD, 17-item; Hamilton, 1960) score ≥ 16, in addition to either a prior suicide attempt, current suicidal ideation or both. Ideation threshold for non-attempters was a score ≥ 2 on the suicide item of the HRSD, endorsing ‘wishes to be dead or has any thought of possible death to self’ (Hamilton, 1960). Patients with clear suicidal intent or plan were only able to participate if they consented to voluntary inpatient admission to our research unit.

Exclusion criteria included bipolar disorder, psychosis, anorexia or bulimia nervosa or drug or alcohol dependence within the past six months, unstable medical illness, lack of capacity to consent, pregnancy or lactation. Patients currently taking an SSRI or bupropion for other indications (such as anxiety), with medical contraindications to either drug, prior nonresponse to three other SSRIs, or paroxetine or bupropion use in the past two years (at least 2/3 maximum approved dose for ≥ 6 weeks) were excluded.

Patients were recruited via local media, internet advertising and clinician referral. Written informed consent was obtained after full description of the study was provided. The study was conducted at a single site at Columbia University Medical Center/New York State Psychiatric Institute with IRB approval.

2.2 Instruments

Diagnoses were established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axes I (SCID-I; First et al., 1998) and II (SCID-II; First et al., 1996). The Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd revision (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1997) were used to estimate premorbid intellectual ability.

Diagnostic and suicide attempt classifications were made in weekly interdisciplinary consensus conferences. History of past suicidal behavior and suicidal events during the course of the study were assessed via structured interview with the Columbia Suicide History Form (Oquendo et al., 2003). Suicidal ideation (clinician-rated Scale for Suicidal Ideation; Beck et al., 1979) and depressive symptoms (HRSD and Beck Depression Inventory; Beck & Steer, 1987) were evaluated weekly. All raters were Master’s or PhD level psychologists.

At baseline and after eight weeks of treatment, patients completed the Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al., 1971), Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ; Broadbent et al., 1982), and a neuropsychological test battery assessing the following domains: Reaction Time (computerized Simple and Choice Reaction Time), Psychomotor functioning (WAIS-III Digit Symbol, Trail Making Test parts A & B), Attention (computerized Continuous Performance Test, Identical Pairs version and Stroop), Memory (Buschke Selective Reminding Task and Benton Visual Retention Test, Administration D), Working Memory (computerized A Not B Reasoning and N-Back), Language Fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Tests using Letters and Category [animals]), and Impulse Control (computerized Go-No Go and Time Production).

Reaction Time tests and Impulse Control tasks were randomized for each administration. Alternate forms were available for all other tests with the exception of the Stroop and Category Fluency, neither of which exhibited practice effects in pilot or previous studies (Fallon et al., 2008). The computerized measures have been described previously in detail (Sackeim et al., 2001; Keilp et al., 2005) and have demonstrated utility in detecting neurocognitive deficits associated with suicidal behavior and depression (Keilp et al., 2001; Keilp et al., 2013). Scores on primary measures from each test were z transformed relative to either published norms or a reference sample of healthy controls and adjusted for the effects of age, gender, and education. Domain scores represent the average of the z scores for the primary score of each test within each neurocognitive domain. To characterize overall performance, the six domain scores were averaged to produce a neurocognitive “index” score.

2.3 Procedures

Patients, psychiatrists and assessors were blind to treatment. Assessors were blind to patients’ clinical status. Following informed consent, patients were randomized to treatment with extended-release forms of either paroxetine or bupropion and completed baseline ratings and neuropsychological testing. Patients met weekly with a study psychiatrist for pharmacotherapy and a psychologist for clinical ratings. Daily medication dose was paroxetine 25 mg or bupropion 150 mg in weeks 1 and 2, and paroxetine 37.5 mg or bupropion 300 mg in weeks 3 and 4. Protocol permitted increases to paroxetine 50 mg or bupropion 450 for the following weeks if clinically indicated. Concomitant treatment with benzodiazepine (up to lorazepam 6 mg daily or its equivalent) for anxiety or zolpidem for insomnia was permitted. Neuropsychological testing was repeated after eight weeks of treatment.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Patients who completed the study were compared with those who dropped out of treatment on demographic, clinical and neurocognitive measures using chi-squared analyses and t-tests.

The remaining analyses exclusively utilized subjects who completed the post-treatment neuropsychological battery. Patients were divided by drug treatment group. Groups were first compared on demographic and clinical variables with chi-square analyses and t-tests.

Two prior communications have reported on treatment response in this clinical trial (Grunebaum et al., 2012; Grunebaum et al., 2013). However, since the current sample was a subset of the full clinical trial sample (n = 74) for whom neuropsychological data were available, we re-analyzed clinical response. Clinical response was defined as >50% decline in HDRS-24 score. Chi-squared analyses were used to examine clinical response rates between drug groups. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine treatment-related changes in depression and ideation measures between drug groups.

Repeated measures ANOVA including all neurocognitive domain scores was used to assess overall neurocognitive performance changes from treatment between drug groups. Repeated measures ANOVA was also performed by drug group for each domain and neuropsychological test independently.

Patients were combined across drug groups to look at the relationship between changes in clinical ratings and changes in neurocognitive performance related to treatment. Hamilton-24 scores were used to track clinical response to treatment. Change scores in neurocognitive tests were compared between clinical responders and non-responders using t tests. Correlations were performed across drug groups between neurocognitive domains and both SSI and HDRS-23 scores (with the suicide item removed), and between specific neuropsychological tests and both SSI and HDRS-23 scores.

3. Results

3.1 Dropout Analysis

A total of 76 patients enrolled in the neuropsychological arm of the study. Of these subjects, 14 were excluded from analyses. Two were dropped prior to beginning study drug due to the emergence of exclusionary symptoms (i.e. mania, psychosis). Five subjects’ baseline test data were invalid: one began treatment with significant doses of pain medication that affected the sensorium, and four did not cooperate with neuropsychological test procedures. At follow-up, test data for two subjects could not be used due to fatigue and poor cooperation at time of assessment.

The remaining 67 subjects were initially randomized and tested at baseline, but 10 dropped out before a second assessment. Dropouts were equally distributed between medication groups. Dropouts were comparable to study completers in terms of demographics and clinical severity, but trended toward having a higher percentage of non-native English speakers (40.0% vs. 15.8%, χ2[1] = 3.19, P = 0.07). Accordingly, dropouts had lower WAIS-III Vocabulary subtest scores (scaled score 10.9 ± 5.3 vs. 13.4 ± 3.1; t[64] = 2.00, P = 0.05), though did not differ from completers in overall estimate of intelligence based on a combination of scores on WAIS-III Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning (average scaled score 12.8 ± 2.7 vs. 13.4 ± 3.1; t[64] = 0.69, P = 0.49). The most significant differences between dropouts and completers were the dropouts’ higher percentage of subjects with prior suicide attempts (90.0% vs. 49.1%; χ2[1] = 4.96, P = 0.03) and poorer performance on impulse control tasks (Impulse Control domain score −0.54 ± 0.63 vs. 0.17 ± 0.89; t[65] = 2.44, P = 0.02). Compared to completers, dropouts, then, were more likely to be non-native English-speaking past suicide attempters with more impulsive behavioral performance.

3.2 Treatment Group Characteristics

In total, 57 patients successfully completed neuropsychological testing at baseline and eight-week follow up. Demographic and clinical characteristics of completing participants are presented in Table 1. At baseline, drug-assignment groups were comparable in age, sex distribution, education, estimated intelligence, and depression severity. Treatment groups did not differ with respect to comorbid cluster B personality disorder, percentage of past suicide attempters, or trait measures of aggression, impulsivity or hostility.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Rating Data

| Bupropion | Paroxetine | P-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 30 | -- |

| Age (yrs.) | 38.9 ± 11.5 | 36.3 ± 12.5 | 0.41 |

| Sex (% Female) | 51.9% (14) | 53.3% (16) | 0.91 |

| Education (yrs.) | 16.2 ± 2.8 | 15.1 ± 2.0 | 0.09 |

| IQ Estimate2 | 12.7 ± 2.4 | 12.9 ± 2.9 | 0.78 |

| Native English Speaking | 85.20% | 83.30% | 0.85 |

| HDRS (24-item)3 | 26.8 ± 7.6 | 25.6 ± 8.9 | 0.59 |

| BDI4 | 28.4 ± 9.6 | 27.4 ± 11.4 | 0.74 |

| Number Dep. Episodes | 11.3 ± 16.3 [median=5.0] | 11.1 ± 16.6 [median=3.0] | 0.97 |

| Current Dep. Episode (wks) | 57.9 ± 76.9 [median=22.0] | 82.2 ± 126.1 [median=36.0] | 0.50 |

| Axis II Diagnosis (% Cluster B) | 18.5% (5) | 16.7% (5) | 0.85 |

| Lifetime Substance Use Disorder | 40.7% (11) | 40.0% (12) | 0.96 |

| Past Suicide Attempt (%) | 44.4% (12) | 53.3% (16) | 0.50 |

| Max. Attempt Lethality | 2.4 ± 2.0 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 0.57 |

| Scale for Suicide Ideation | 11.0 ± 7.7 | 7.3 ± 6.5 | 0.06 |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale | 59.8 ± 15.9 | 57.6 ± 17.9 | 0.63 |

| Brown-Goodwin Aggression History | 20.2 ± 6.7 | 19.7 ± 5.9 | 0.77 |

t-test for continuous variables, chi-squared for categorical variables.

WAIS-III Vocabulary/Matrix Reasoning Average

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Beck Depression Inventory

3.3 Treatment Response

Treatment response data are presented in Table 2. Depression improved with treatment, with each group demonstrating a decline in HDRS-24 severity of just over 10 points (average 34.2 ± 64.1% decline). Overall, 47.4% of treated patients met criteria for clinical response (>50% decline in HDRS-24 score), with equivalent response rates in each treatment group (48.1% bupropion, 46.7% paroxetine; χ2[1] = 0.01, P = 0.91). Similar improvements were observed on the BDI and POMS. Suicidal ideation declined significantly in both drug groups, though was greater at both time points in the bupropion treated group. Subjective neurocognitive complaints declined with treatment, with a trend toward greater improvement in the bupropiontreated group.

Table 2.

Treatment Effects: Clinical Rating Data

| Bupropion | Paroxetine | Effect (P-value)1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post- Treatment |

Baseline | Post- Treatment |

Time | Group | Time × Group | |

| HDRS-242 | 26.8 ± 7.6 | 16.9 ± 11.5 | 25.6 ± 8.9 | 14.0 ± 8.6 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.51 |

| BDI3 | 28.4 ± 9.8 | 15.4 ± 13.0 | 27.4 ± 11.4 | 12.7 ± 9.9 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.49 |

| SSI4 | 11.0 ± 7.7 | 6.2 ± 7.8 | 7.3 ± 6.5 | 2.4 ± 4.5 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.94 |

| POMS5 | 114.4 ± 32.3 | 61.9 ± 48.9 | 115.0 ± 34.8 | 67.2 ± 49.6 | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| CFQ6 | 53.3 ± 14.9 | 43.5 ± 15.3 | 47.5 ± 15.7 | 43.9 ± 19.6 | 0.001 | 0.50 | 0.11 |

Repeated measures ANOVA.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Beck Depression Inventory

Scale of Suicidal Ideation

Profile of Mood States, Total score

Cognitive Failures Questionnaire, Total score

3.4 Neuropsychological Test Performance

When comparing pre and post-treatment neuropsychological test performance between drug groups (Table 3), there was an overall effect of time (F[1,53] = 35.80, P < 0.001) and a time by domain interaction (F[6,318] = 4.84, P < 0.001). There was, however, no time by drug interaction (F[1,53] = 0.26, P = 0.61), nor a time by test domain by drug interaction (F[6,318] = 1.33, P = 0.24). There also was no aggregate drug group effect across time points (F[1,53] = 0.09, P = 0.77).

Table 3.

Neuropsychological tests by drug group

| Bupropion | Paroxetine | Effect (P-value)1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post- Treatment |

Baseline | Post- Treatment |

Time | Group | Time × Group | |

| Reaction Time | −0.36 ± 1.27 | −0.45 ± 1.23 | −0.06 ± 0.86 | −.2 20 ± 0.90 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.79 |

| Simple RT | −0.22 ± 1.76 | −0.44 ± 1.74 | −0.23 ± 1.12 | −0.67 ± 1.38 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.58 |

| Choice RT | −0.44 ± 1.54 | −0.40 ± 1.82 | −0.10 ± 1.27 | 0.24 ± 1.18 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.71 |

| Psychomotor | −0.01 ± 0.81 | 0.22 ± 0.70 | −0.46 ± 0.66 | 0.15 ± 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Trail Making A | −0.09 ± 1.00 | 0.32 ± 1.01 | −0.57 ± 0.98 | 0.00 ± 0.97 | 0.003 | 0.07 | 0.60 |

| Trail Making B | −0.14 ± 1.12 | −0.12 ± 0.97 | −0.69 ± 1.03 | 0.16 ± 1.11 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.01 |

| Digit Symbol | 0.10 ± 1.04 | 0.33 ± 0.92 | −0.29 ± 0.66 | 0.22 ± 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.05 |

| Attention | −0.17 ± 0.79 | −0.21 ± 0.85 | 0.14 ± 0.83 | 0.17 ± 0.60 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.73 |

| CPT (d’) | −0.12 ± 0.81 | 0.23 ± 0.82 | −0.37 ± 1.10 | 0.23 ± 1.10 | <0.001 | 0.61 | 0.29 |

| Stroop Interference | −0.21 ± 1.30 | 0.05 ± 1.44 | −0.04 ± 1.36 | 0.10 ± 0.91 | 0.19 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| Memory | −0.65 ± 1.14 | −0.07 ± 1.18 | −0.33 ± 1.07 | −0.03 ± 0.94 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 0.19 |

| Buschke SRT Total | −0.57 ± 1.33 | −0.10 ± 1.36 | −0.23 ± 1.39 | 0.10 ± 1.30 | 0.004 | 0.44 | 0.58 |

| Benton VRT | −0.73 ± 1.56 | −0.03 ± 1.33 | −0.37 ± 1.10 | −0.16 ± 1.07 | 0.002 | 0.71 | 0.10 |

| Working Memory | −0.35 ± 0.75 | 0.02 ± 0.73 | −0.47 ± 1.15 | −0.18 ± 1.14 | 0.002 | 0.52 | 0.68 |

| N-Back (d’) | −0.58 ± 1.12 | −0.23 ± 0.96 | −0.55 ± 1.18 | −0.47 ± 1.30 | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.35 |

| A Not B Reasoning2 | −0.10 ± 0.69 | 0.24 ± 1.02 | −0.38 ± 1.51 | 0.11 ± 1.70 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.68 |

| Language Fluency | −0.06 ± 0.78 | 0.02 ± 0.73 | −0.17 ± 0.88 | −0.06 ± 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.65 | 0.83 |

| Letter Fluency | −0.08 ± 0.94 | 0.12 ± 1.00 | −0.19 ± 1.16 | 0.10 ± 1.11 | 0.008 | 0.83 | 0.58 |

| Category Fluency | −0.04 ± 0.84 | −0.07 ± 0.77 | −0.15 ± 0.88 | −0.22 ± 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.87 |

| Impulse Control | 0.11 ± 0.68 | 0.09 ± 0.65 | −0.20 ± 0.76 | 0.01 ± 0.70 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.15 |

| Go-No Go3 | −0.04 ± 1.04 | −0.06 ± 0.89 | −0.53 ± 1.00 | −0.09 ± 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.06 |

| Time Production4 | 0.30 ± 0.75 | 0.26 ± 0.78 | 0.13 ± 0.97 | 0.11 ± 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.97 |

Repeated measures ANOVA

Median RT

Commission Errors

Deviation score

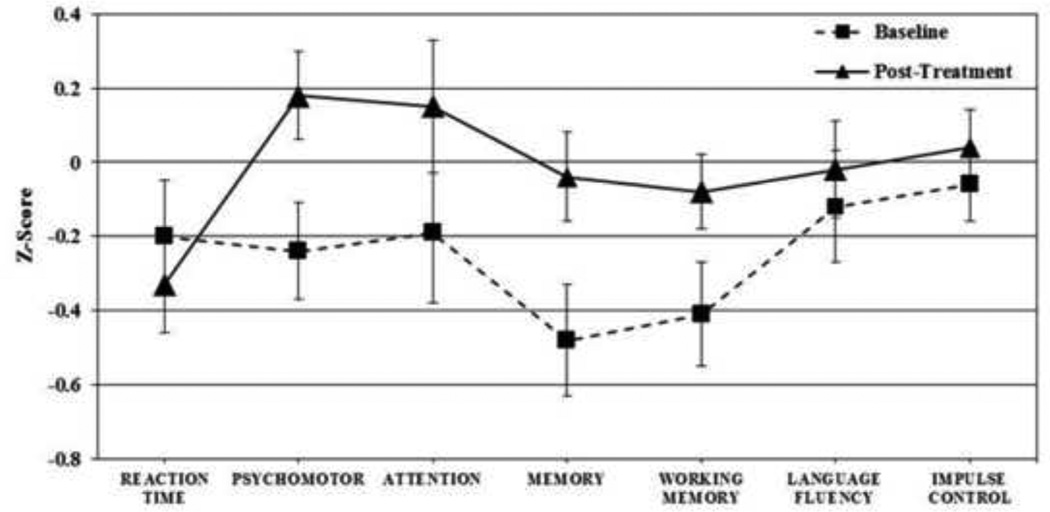

In sum, there was general improvement in test performance that was concentrated within specific domains, but no differential drug effects for global neurocognitive function or particular neurocognitive domains in this omnibus analysis. Changes in neuropsychological functioning across treatment groups are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cognitive change in response to treatment across drug groups.

When drug treatment groups were analyzed together (without consideration of drug assignment), the time (F[1,54] = 36.74, P < .001) and time by domain effects (F[6,324] = 4.83, P < 0.001) remained significant. Significant change over time was found in Psychomotor (t[54] = 5.40, P < 0.001; effect size = 0.43), Attention (t[54] = 3.78, P < 0.001; effect size = 0.35), Memory (t[54] = 4.05, P < 0.001; effect size = 0.43) and Working Memory (t[54] = 3.28, P = 0.002; effect size = 0.33) domains.

Treatment effects for both groups were observed for specific measures within psychomotor, attention, memory and working memory domains. Improvement was significant on Trail Making A and B, WAIS-III Digit Symbol, CPT, Buschke SRT, Benton VRT, and the A Not B timed reasoning test Letter fluency improved with treatment, but was offset in the language fluency domain by a slight decline in category fluency performance.

There were no differential drug effects observed in an omnibus analysis across all tests, but a differential drug effect was observed in the psychomotor domain when analyzed alone. Paroxetine treated subjects showed greater improvement on Trail Making Part B and WAIS-III Digit Symbol. They also showed a trend toward greater improvement in Go-No Go performance, due in part to their poorer performance at baseline.

3.5 Relationship of Neuropsychological to Clinical Improvement

Across both drugs, treatment responders and non-responders were comparable in terms of neurocognitive change, with the exception of the memory domain where responders showed greater improvement (change of 0.67 ± 0.74 SD vs. 0.22 ± 0.80 SD; t[53] = 2.13, P = 0.04). This was most pronounced on the Buschke SRT (0.67 ± 0.98 SD vs. 0.14 ± 0.87 SD; t[52] = 2.08, P = 0.04).

Within the entire patient sample, improvement in memory domain scores correlated with decline in both the HDRS-23 (suicide item removed) (r = −0.35, P = 0.004) and SSI (r = −0.39, P = 0.003). This was primarily attributable to specific improvement in Buschke SRT performance (associated with both decline in HDRS-23 (r = −0.35, P = .004) and SSI (r = −0.51, P < 0.001)).

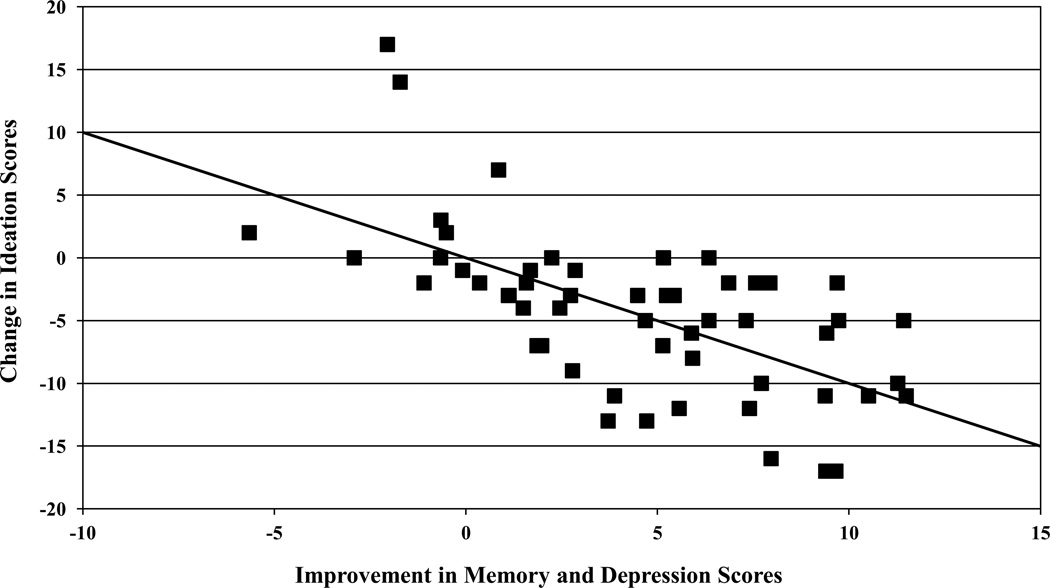

Notably, while improved Buschke SRT performance was associated with both reduction in depression severity and reduced suicidal ideation (significant correlation between lower SSI and lower HDRS-23, r = 0.52, P < 0.001), the correlation between change in Buschke SRT and change in suicidal ideation scores remained significant after controlling for the change in HDRS-23 depressive symptoms (partial r = −0.41, P = 0.002). Thus, there appears to be an independent association between memory improvement and the reduction in suicidal ideation. Using both the change in HDRS-23 and change in Buschke SRT scores in a regression equation to predict the change in SSI score, each contributed independently (change in HDRS-23 standardized β = 0.39, P = 0.002; change in Buschke SRT standardized β = −0.38, P = 0.002) and the overall equation was significant (Multiple R = 0.63, F[2,53] = 16.63, P < 0.001). These data are shown in Figure 2. While depression symptom change scores accounted for 27 percent of suicidal ideation change score variance, depression and memory improvement together accounted for 40 percent.

Figure 2.

Linear combination of change scores in HDRS-24 and Buschke SRT predict change in suicidal ideation scores

4. Discussion

In this sample of patients at elevated risk for suicidal behavior, there was overall improvement in neurocognitive functioning following antidepressant treatment irrespective of drug type. Data did not support our hypothesis regarding bupropion yielding greater improvement in neurocognitive functioning. There was trend-level support for our hypothesis that paroxetine would produce greater improvement on tests of impulsivity but this did not reach significance. There were few individual drug effects on neuropsychological measures. Paroxetine was paradoxically associated with a greater improvement in psychomotor performance, though this was only significant when neurocognitive domains were compared individually. The magnitude of neurocognitive improvement across drug treatment groups was greater than that typically attributable to practice effects (see Fallon et al., 2008 for changes in healthy comparison subjects after repeated testing on many of the same measures, where improvement with practice averaged 0.10 SD with each repeated administration). Use of alternate forms of tests also indicates that improvement was not due to familiarity with the test stimuli. Significant changes across drug treatment groups were found in Psychomotor, Attention, Memory and Working Memory domains. The magnitude of improvement is reasonable given the moderate levels of cognitive impairment associated with depression and suicidal behavior.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of neurocognitive improvement in the context of antidepressant treatment in a sample where all patients are at elevated risk for suicidal behavior. While neither medication was superior in this modest-sized sample, post-treatment test scores were similar to those in normative samples, with z-scores around zero in most neurocognitive domains. This indicates that antidepressant treatment is capable of normalizing neurocognitive deficits in patients with elevated suicide risk, including those in the attention and memory domains, which have consistently been shown to be associated with suicidal behavior (Keilp et al., 2013; Jollant et al., 2011; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2014a; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2014b). Patients also reported improvement on a subjective measure of cognitive difficulties, but this subjective report did not correlate with changes on the neurocognitive measures themselves. Neurocognitive test results were not consistent with prior reports of enhanced cognitive functioning with bupropion treatment in depression, which may be attributable to the exclusion of patients with elevated suicide risk in these studies. Patients with histories of suicidal behavior tend to have more severe cognitive impairments than non-attempter depressed groups (Keilp et al., 2001; Keilp et al., 2008; Dombrovski et al., 2008; Jollant et al., 2011; Keilp et al., 2013) and may therefore demonstrate less robust cognitive changes with bupropion.

The attrition rate in the broader treatment trial of which this study was a part was comparable to that of other clinical trials in MDD (Grunebaum et al., 2012), and exceeded the drop-out rate of the patients who participated in neuropsychological testing. However, patients who completed baseline neurocognitive assessment and subsequently dropped out of the study were more likely to have made a prior suicide attempt and had significantly poorer scores on tests within the impulse control domain. These dropouts may be at greatest risk for suicidal behavior and among those who might benefit the most from treatment. More extensive efforts may be needed to ensure their continued compliance in both research and clinical settings. In addition, their withdrawal from the study may have attenuated the range of scores on measures of impulse control, and contributed to the lack of change in this domain following antidepressant treatment.

Verbal memory deficits are a consistent finding in depressed suicide attempter samples (Keilp et al., 2001; Dumbrovski et al., 2008; Westheide et al., 2008; Keilp et al., 2013). Results here suggest that verbal memory impairment has an independent relationship with suicidal ideation, extending beyond the association of both of these factors with depression severity. Improvement in verbal memory was associated with reduced suicidal ideation even after controlling for the improvement in depression severity, and in combination they explained 40% of the variance in the reduction of suicidal ideation. The mechanism of this association is unclear, but this finding emphasizes the need to assess cognition in determining suicidal behavior risk. It also suggests that the relationship of memory dysfunction to suicidal ideation may merit further investigation.

The main limitation of this study was its small sample size, as well as selective attrition. Additional clinical trials with larger samples of patients at high risk for suicide are needed to inform treatment options for this population of high public health importance, and are feasible with careful monitoring. However, suicidal patients are a highly selected group, difficult to recruit, retain, and requiring intensive follow-up, so larger trials may necessitate multi-center studies. Medications used in this study may not have had sufficiently distinct mechanisms of action to yield differential treatment effects. Heterogeneity of both the depressive and suicidal phenotypes may have obscured detection of potential differential medication effects. Finally, interactions between the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems may have contributed to the apparent lack of differential drug effects (Dong & Blier, 2001; Healy & McKeon, 2000).

Overall, these results indicate that both mood and cognition can be improved with antidepressant medication in patients at risk for suicidal behavior, but special care must be taken to retain patients who are impulsive, less verbal, and ethnically diverse. With respect to treating neurocognitive dysfunction in depression, there appears to be equivalency across the antidepressants used in this study, although paroxetine showed a slight advantage for improving psychomotor performance. Suicidal ideation declined in conjunction with improvement in depression severity, but improved memory also played an independent role in reducing suicidal ideation. Further antidepressant treatment studies designed to improve memory and other aspects of neurocognitive functioning as a method of reducing suicide risk are needed.

Highlights.

A comprehensive neuropsychological battery was administered to depressed patients at elevated risk for suicide before and after treatment in a clinical trial

Patients were treated with paroxetine or bupropion for eight weeks

Neurocognitive functioning improved after treatment in all patients, without clear advantage for either medication

Improvement in memory performance was associated with reduced suicidal ideation independent of the improvement of depression severity

Targeted treatment of neurocognitive dysfunction may bring about greater reduction in risk for reducing suicidal behavior

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by grants from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, NARSAD and NIMH (K23-MH076049, MH48514, MH62185).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Banaschewski T, Roessner V, Dittmann RW, Santosh PJ, Rothenberger A. Non-stimulant medications in the treatment of ADHD. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;13:I102–I116. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-1010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrickman LL, Perry PJ, Allen AJ, Kuperman S, Arndt SV, Herrmann KJ, Schumacher E. Bupropion versus methylphenidate in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:649–657. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Booij L, Van der Does AJ, Riedel WJ. Monoamine depletion in psychiatric and healthy populations: review. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:951–973. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, Parkes KR. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;21:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay TH, Gualtieri CT, Evans RW, Gullion CM. Clinical and neuropsychological effects of the novel antidepressant bupropion. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1988;24:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constant EL, Adam S, Gillain B, Seron X, Bruyer R, Seghers A. Effects of sertraline on depressive symptoms and attentional and executive functions in major depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;21:78–89. doi: 10.1002/da.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, Clark L, Mazumdar S, Szanto K. Cognitive performance in suicidal depressed elderly: preliminary report. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:109–115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180f6338d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Blier P. Modification of norepinephrine and serotonin, but not dopamine, neuron firing by sustained bupropion treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155:52–57. doi: 10.1007/s002130000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon BA, Keilp JG, Corbera KM, Petkova E, Britton CB, Dwyer E, Slavov I, Cheng J, Dobkin J, Nelson DR, Sackeim HA. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated IV antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology. 2008;70:992–1003. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000284604.61160.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Graves LM, Benazzi F, Scalia MJ, Iosifescu DV, Alpert JE, Papakostas GI. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence of cognitive and physical symptoms during long-term antidepressant treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1754–1759. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JM, Wesnes KA, Schwartz GE. Reboxetine versus paroxetine versus placebo: effects on cognitive functioning in depressed patients. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;18:9–14. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Version 2.0. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Benjamin L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Version 2.0. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gallassi R, Di Sarro R, Morreale A, Amore M. Memory impairment in patients with late-onset major depression: the effect of antidepressant therapy. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Ellis SP, Duan N, Burke AK, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Pilot randomized clinical trial of an SSRI vs bupropion: effects on suicidal behavior, ideation, and mood in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:697–706. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Keilp JG, Ellis SP, Sudol K, Bauer N, Burke AK, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. SSRI versus bupropion effects on symptom clusters in suicidal depression: Post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;79:872–879. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG. Bupropion normalizes cognitive performance in patients with depression. Medscape General Medicine. 2007;9:22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy E, McKeon P. Dopaminergic sensitivity and prediction of antidepressant response. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2000;14:152–156. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lonnqvist JK. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:935–940. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Guzman I, Gudayol-Ferre E, Herrera-Abarca JE, Herrera-Guzman D, Montelongo-Pedraza P, Padros Blazquez F, Pero-Cebollero M, Guardia-Olmos J. Major Depressive Disorder in recovery and neuropsychological functioning: effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and dual inhibitor depression treatments on residual cognitive deficits in patients with Major Depressive Disorder in recovery. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;123:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Guzman I, Gudayol-Ferre E, Herrera-Guzman D, Guardia-Olmos J, Hinojosa-Calvo E, Herrera-Abarca JE. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake and dual serotonergic-noradrenergic reuptake treatments on memory and mental processing speed in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Guzman I, Gudayol-Ferre E, Lira-Mandujano J, Herrera-Abarca J, Herrera-Guzman D, Montoya-Perez K, Guardia-Olmos J. Cognitive predictors of treatment response to bupropion and cognitive effects of bupropion in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2008;160:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2006;145:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jollant F, Lawrence NL, Olie E, Guillaume S, Courtet P. The suicidal mind and brain: a review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2011;12:319–339. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Attention deficit in depressed suicide attempters. Psychiatry Research. 2008;159:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Russell M, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Harkavy-Friedman J, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior: attention control, memory and executive dysfunction in suicide attempt. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:539–551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Sackeim HA, Brodsky BS, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological dysfunction in depressed suicide attempters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:735–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Sackeim HA, Mann JJ. Correlates of trait impulsiveness in performance measures and neuropsychological tests. Psychiatry Research. 2005;135:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DA, Conwell Y, Cox C, Henderson RE, Denning DG, Caine ED. A neuropsychological comparison of depressed suicide attempters and nonattempters. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2000;12:64–70. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer M, Ising M, Kunzel H, Binder EB, Holsboer F, Modell S, Zihl J. Impaired divided attention predicts delayed response and risk to relapse in subjects with depressive disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1453–1463. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon AC, Portera L. Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 2005;112:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lour M, Droppleman JF. Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Iacoviello B, Neumeister A, Charney DS, Iosifescu DV. Cognitive dysfunction in depression: neurocircuitry and new therapeutic strategies. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2011;96:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ. Risk factors for suicidal behavior: The utility and limitations of research instruments. In: First M, editor. Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice, Review of Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003. pp. 102–130. [Google Scholar]

- Paelecke-Habermann Y, Pohl J, Leplow B. Attention and executive functions in remitted major depression patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;89:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard-Devantoy S, Berlim MT, Jollant F. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological markers of vulnerability to suicidal behavior in mood disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2014a;44:1663–1673. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard-Devantoy S, Berlim MT, Jollant F. Suicidal behaviour and memory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2014b;12:1–23. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2014.925584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackeim HA, Keilp JG, Rush AJ, George MS, Marangell LB, Dormer JS, Burt T, Lisanby SH, Husain M, Cullum CM, Oliver N, Zboyan H. The effects of vagus nerve stimulation on cognitive performance in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology. 2001;14:53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. third edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Westheide J, Quednow BB, Kuhn KU, Hoppe C, Cooper-Mahkorn D, Hawellek B, Eichler P, Maier W, Wagner M. Executive performance of depressed suicide attempters: the role of suicidal ideation. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;258:414–421. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Haight BR, Horrigan JP, Hudziak JJ, Rosenthal NE, Connor DF, Hampton KD, Richard NE, Modell JG. Bupropion XL in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]