Abstract

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED) is the only adult psychiatric diagnosis for which pathological aggression is primary. DSM-IV criteria focused on physical aggression, but DSM-5 allows for an IED diagnosis in the presence of frequent verbal aggression with or without concurrent physical aggression. It remains unclear how individuals with verbal aggression differ from those with physical aggression with respect to cognitive-affective deficits and psychosocial functioning. The current study compared individuals who met IED criteria with either frequent verbal aggression without physical aggression (IED-V), physical aggression without frequent verbal aggression (IED-P), or both frequent verbal aggression and physical aggression (IED-B) as well as a non-aggressive personality-disordered (PD) comparison group using behavioral and self-report measures of aggression, anger, impulsivity, and affective lability, and psychosocial impairment. Results indicate all IED groups showed increased anger/aggression, psychosocial impairment, and affective lability relative to the PD group. The IED-B group showed greater trait anger, anger dyscontrol, and aggression compared to the IED-V and IED-P groups. Overall, the IED-V and IED-P groups reported comparable deficits and impairment. These results support the inclusion of verbal aggression within the IED criteria and suggest a more severe profile for individuals who engage in both frequent verbal arguments and repeated physical aggression.

Keywords: Intermittent Explosive Disorder, Aggression, Anger

1. Introduction

Although aggression is a recognized global health concern (Krug et al., 2002), and most aggression is affective in nature (Averill, 1983), there exists only one psychiatric diagnosis for which affective aggression is the core symptom: Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), IED is defined as the failure to resist aggressive impulses that result in repeated acts of verbal and/or physical aggression (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). The inclusion of verbal aggression represents a major change over previous iterations of IED in the DSM.

IED is both common, with lifetime prevalence rates of 5.4% to 7.3%, (Kessler et al., 2005; Coccaro et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2006; Ortega et al., 2008) and highly impairing. IED is associated with substantial distress, health problems, troubled relationships, occupational difficulty, and legal or financial problems (McElroy et al., 1998; McCloskey et al., 2010). Individuals with IED are rated as lower in overall psychosocial functioning than healthy volunteers or psychiatric controls (McCloskey et al., 2006; McCloskey et al., 2008a). In addition, IED has been associated with several cognitive-affective deficits, including poor impulse control and affect dysregulation.

Individuals with IED report increased impulsivity on self-report measures, but do not appear more impulsive on validated laboratory tasks of impulsivity (Coccaro et al., 1998; Best et al., 2002). An argument could be made that the heterogeneity of “impulsivity” across measures (Evenden, 1999; Whiteside and Lynam, 2003) is likely to be responsible for this inconsistency. However, the relationship between IED and general impulsivity has been ephemeral even within the same measure (e.g., BIS) (Coccaro et al., 1998; Best et al., 2002). This suggests that IED may not be wholly characterized as a problem of impulse control and that the aggressive outbursts may be more related to other constructs, such as emotion regulation. Individuals with IED have difficulty regulating their behavior under periods of extreme stress or intense emotion, particularly anger (Davidson et al., 2000; Siever, 2008). This difficulty regulating emotion does not appear to be limited to anger; IED is significantly associated with deficits in overall affect regulation relative to both healthy volunteers and other psychiatric populations (Coccaro et al., 1998; McCloskey et al., 2006; McCloskey et al., 2008).

Despite marked cognitive-affective deficits and psychosocial impairment, empirical research on IED has been limited. This is partially due to a lack of congruence in defining the disorder. Prior to DSM-5, an IED diagnosis was limited to individuals who reported physical aggression. This may be related to the fact that physical aggression is often considered more severe than verbal aggression (e.g., Solari & Baldwin, 2002). However, studies showed that individuals with frequent verbal aggression (i.e., two or more times a week for a month or more) reported similar levels of anger, aggression, and impairment comparable to their IED counterparts, most of whom had high levels of both verbal and physical aggression (McCloskey et al., 2006; Coccaro, 2011; Coccaro, 2012). These findings have, in part, led to the inclusion of verbal aggression in DSM-5 IED. However, there has been limited research comparing “pure” verbal and physical sub-types of IED. McCloskey and colleagues (2008a) found no differences between an IED group with both physical and verbal aggression and a verbally aggressive group on measures of trait aggression, trait anger, and clinical impairment, with both groups showing more aggression, anger, and impairment than a psychiatric control group. However, no study to date has directly compared individuals with pathological physical (but not verbal) aggression to those with pathological levels of verbal (but not physical aggression). Understanding how these aggressive groups differ in terms of cognitive-affective functioning and psychosocial impairment will provide important insight into the homogeneity of the IED diagnosis (Coccaro and Kavoussi, 1997; Coccaro et al., 1998).

The current study examined areas of increased cognitive-affective deficits and psychosocial impairment in three distinct groups of individuals with IED: (1) individuals meeting for IED verbal aggression (i.e., verbal outbursts, such as heated arguments, yelling and cursing, occurring on average at least twice a week for three months or more; IED-V group), (2) individuals meeting IED physical aggression criteria (i.e. either three assaults on people, animals, or property with damage/injury over a 12 month period or an average of two assaults on people, animals or property without injury / damage a week for 3 months; IED-P group), (3) individuals met both physical and verbal IED criteria; IED-B group). The three IED variants were compared to each other as well as to a psychiatric control group consisting of individuals diagnosed with a personality disorder, including personality disorder not otherwise specified, who did not meet any of the DSM-5 IED aggression criteria (PD group). All participants were assessed for the severity of deficits in anger, anger dyscontrol, and aggression using a multi-method approach that included behavioral, questionnaire, and clinical interview measures. Putative associated constructs of affective lability, impulsivity, and psychosocial functioning were also assessed.

It was predicted that IED-V participants would report less physical aggression than the other IED groups, whereas IED-P participants would report less verbal aggression than the other IED groups. No other differences were expected among IED groups on measures of anger, anger dyscontrol, and aggression. Further, it was expected that all IED groups would show higher levels of anger, anger dyscontrol, and aggression relative to the PD control group. Lastly, it was predicted that all IED groups would show decreased psychosocial functioning and increased levels of affect lability and impulsivity compared to the PD control group, but not differ from each other on these constructs.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were 134 men and 168 women between the ages of 18 and 65 (M = 37.27, SD = 9.80) recruited from the community via advertisements for healthy volunteers and individuals with emotional or anger problems as a part of larger ongoing studies of aggression, anger, and personality at the University of Chicago. Participants were excluded if they reported (a) current psychopharmacological treatment or substance dependence, (b) lifetime bipolar or psychotic disorder, (c) a traumatic head injury with loss of consciousness greater than one hour, or (d) current major depression. This study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Participants were predominately Caucasian (62.3%) or African-American (27.2%). Diagnostic groups consisted of: (a) IED-V (n = 41), (b) IED-P (n = 60), (c) IED-B (n = 111), and (d) PD (n = 90).

2.2 Psychiatric Interview Measures

The Intermittent Explosive Disorder Interview (IED-I; Coccaro, 2005) was used to assess DSM-5 IED, Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID; First, 1996) to diagnose non-IED Axis I disorders, and Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SID-P; Pfohl et al.,1995) to diagnose personality disorders. In addition, the Aggression scale of the Life History of Aggression (LHA-A; Coccaro et al., 1997) was administered to assess lifetime (since age 13) frequency of aggressive acts (i.e., temper tantrums, physical fights, verbal aggression, physical assaults on other people [or animals], and assaults on property), and a Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score was assigned after the interview.

2.3 Self-Ratings of Aggression and Associated Constructs

Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss and Perry, 1992) is 29 items self-report measure of trait aggressiveness that includes of four scales: physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility.

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory—2 (STAXI–2; Spielberger, 1999) is a 57-item self-report measure of anger and anger expression/control. Four STAXI-2 scales were used in the current study: Anger Expression-Out (AX-O) and Anger Expression-In (AX-I) which measure how often angry feelings result in aggression and anger suppression, respectively. Anger Control-Out (AC-O) and Anger Control-In (AC-I) scales assess how often individuals attempt to reduce anger and express it constructively.

Barratt Impulsivity Scale 11 (BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995) is an internally consistent (α = 0.79–0.83) 34-item questionnaire of impulsive personality traits in the areas of motoric, attentional, and non-planning impulsiveness.

Affective Lability Scale (ALS; Harvey et al., 1989) is a 54-item questionnaire that assesses propensity to change affective state (higher scores indicate greater affective lability). The ALS contains six scales, four scales that assess lability from euthymia to anger, anxiety, hypomania, and depressed mood and two scales measure vacillation between depression and hypomania (biphasic) and anxiety and depression (anxiety/depression).

Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q; Endicott et al., 1993) is a self-report quality of life measure. For this study, the 15-item Summary scale of the Q-LES-Q was used.

2.4 Behavioral Measures

Taylor Aggression Paradigm (TAP; Taylor, 1967) is a well-validated (McCloskey and Berman, 2003b) laboratory measure of retaliatory aggression. In this task, the participant competes against a fictitious opponent in a reaction-time game during which electric shock is administered and received. Before each trial, the participant selects a shock level for the opponent to receive should the participant have a faster reaction-time on that trial. Aggression is defined as the intensity of the shock selected. In the current study, the dependent variables were defined as both the mean shock selection and the number of extreme (20) shock selections across four provocation blocks.

Immediate Memory Task (IMT; Dougherty and Marsh, 2003) is a behavioral measure of motor impulsivity that consists of a series of briefly presented five-digit numbers on a computer monitor. Subjects are instructed to respond when the five-digit number they see is identical to the one that preceded it. On a third of the trials, the stimulus is a number that differs from the preceding number by only one digit (its position and value determined randomly). Responses to catch stimuli are recorded as commission errors, which are believed to reflect motor impulsivity in this task. The proportion of commission errors to correct detections, known as the IMT ratio, is the primary dependent measure of impulsivity for this task (Dougherty et al., 2008).

2.5 Procedure

On visit 1, participants completed a 3–4 hour diagnostic interview that included the IED interview, SID-P, SCID, and LHA-A. Diagnosticians also assigned a GAF score after the interview. All interviews were conducted by trained graduate-level diagnosticians who were not informed about the study hypotheses. Diagnosticians underwent a rigorous training program, which resulted in good to excellent inter-rater reliabilities (K = 0.84 ± 0.05) across Axis I and Axis II disorders. Final diagnoses were assigned by team best-estimate consensus procedures (Klein et al., 1994). Between visits 1 and 2, participants completed the BPAQ, STAXI-2, BIS, ALS, and Q-LES-Q questionnaires.

On visit 2, participants completed a urine drug test and alcohol breathalyzer test prior to being prepared for the TAP. For the TAP, fingertip electrodes were attached to two of the fingers on the participant’s non-dominant hand. An upper shock pain threshold was determined by administering increasingly intense shocks at 100-microampere intervals until the participant reported the shock “very unpleasant.” To increase the credibility, this procedure was repeated with the other “subject” (an audiotape of a confederate), and overheard by the participant. Next, instructions were provided via intercom to indicate that the task was a reaction-time game. Before each trial, both subjects selected a shock from 0 through 10 or 20. The slower person on each trial received the shock chosen by their opponent before that trial. The 10 shock corresponded to the shock level judged by the participant to be very unpleasant. Shocks 9 through 1 were five percent decrements of the 10 shock, such that 1 was 55% of the maximum threshold. The participant was informed that the 20 shock would administer a “severe” shock, twice the intensity of the 10 (in the one instance the fictitious opponent selects a 20, the participant does not receive the shock because he or she “wins” the trial). Thus, a 20-shock selected by the participant indicated extreme aggression. Participants were also given a 0 (no) shock option.

Participants completed 28 reaction-time trials consisting of an initial trial, followed by four, 6-trial blocks of increasing provocation by the opponent with a transition trial between blocks. The average shock setting by the fictitious opponent across the first three blocks was 2.5, 5.5, and 8.5 respectively. The fourth block differs from the third block only in that a highly aversive 20 shock is selected by the opponent on the first trial of the block. The participant lost (i.e., received the opponent shock) on half the trials, with the frequency of wins and losses preprogrammed by the experimenter. After the TAP, the participant was debriefed to determine the participant’s level of insight into the task (i.e., deception component and purpose).

3. Results

Analyses were conducted two-tailed at the 0.05 level of significance. For measures comprised of multiple scales, MANOVA analyses were first used to examine multivariate effects of diagnostic status and gender as well as gender*group interactions. Subsequent univariate analyses were performed to examine the main effect of diagnostic group, gender, and gender*group interactions. For significant group main effects resulting from ANOVA analyses, post-hoc mean comparisons were done using Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). For significant interactions, simple effects analyses were performed. For significant χ2 analyses, single degree of freedom χ2 analyses were performed post-hoc to determine significant differences of proportions between groups. Effect sizes are provided using partial eta squared (ήp2) for analyses of variance. For ήp2, 0.01, 0.06 and 0.14 are considered small, medium and large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988).

It should be noted that 38 subjects either did not complete the TAP (n = 27) or did not believe the deception (n = 11). Thus, for analyses using the TAP, there are a total of 264 participants (34 IED-V, 57 IED-P, 96 IED-B, and 77 PD).

Preliminary Analyses

Inter-correlations among Study Variables

As shown in Table 1, most measures of anger and aggression (e.g., BPAQ, LHA-A, STAXI-2) were significantly correlated with each other. TAP mean shock correlated with the anger/aggression variables, except AX-I and AC-I. However, TAP extreme (20) shocks only correlated with mean TAP shock, BPAQ verbal and physical aggression scales, and LHA-A.

Table 1.

Inter-correlations among study measures of aggression and anger (N = 264)

| Measure | TAP- 20 |

BPA- P |

BPA- V |

BPA- A |

BPA- H |

LHA | STAXI -CI |

STAXI -CO |

STAXI -EI |

STAXI -EO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAP-M | 0.58** | 0.25** | 0.20** | 0.16* | 0.13* | 0.22** | −0.08 | −0.12* | 0.02 | 0.17** |

| TAP-20 | 0.20** | 0.16* | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.14* | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.04 | |

| BPA-P | 0.58** | 0.66** | 0.54** | 0.56** | −0.26** | −0.37** | 0.15* | 0.51** | ||

| BPA-V | 0.71** | 0.50** | 0.43** | −0.28** | −0.41** | 0.13* | 0.53** | |||

| BPA-A | 0.59** | 0.54** | −0.45** | −0.60** | 0.20** | 0.63** | ||||

| BPA-H | 0.33** | −0.30** | −0.28** | 0.38** | 0.38** | |||||

| LHA-A | −0.36** | −0.53** | 0.08 | 0.55** | ||||||

| STAXI-CI | 0.71** | −0.24** | −0.50** | |||||||

| STAXI-CO | −0.04 | −0.67** | ||||||||

| STAXI-EI | 0.25** |

Note. TAP = Taylor Aggression Paradigm; TAP–M = TAP mean shock setting; TAP-20 = number of TAP extreme (“20” shock) aggression; BPA = Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire; BPA-P = BPA Physical Aggression Scale; BPA-V = BPA Verbal Aggression Scale; BPA-A = BPA Anger Scale; BPA-H = BPA Hostility Scale; LHA = Life History of Aggression-Aggression scale; STAXI-2 = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory; STAXI-CI = STAXI-2 Anger Control-In scale; STAXI-CO = STAXI-2 Anger Control-Out scale; STAXI-EI = STAXI-2 Anger Expression-In scale; STAXI-EO = STAXI-2 Anger Expression-Out scale.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Likewise, inter-correlations between measures of affect lability, psychosocial functioning, and impulsivity were high both within and across scales (Table 2). The IMT was an exception; it was not associated with self-report measures of impulsivity or affective lability, and was negatively correlated with measures of psychosocial functioning.

Table 2.

Inter-correlations among study measures of impulsivity, affective lability, and psychosocial functioning (N = 302)

| Measure | BIS -A |

BIS- M |

BIS- N |

ALS- D |

ALS- H |

ALS- B |

ALS- X |

ALS- A |

ALS- X/D |

GAF | Q- LES- Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMT | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.04 | −0.16** | −0.18** |

| BIS-A | 0.54** | 0.42** | 0.42** | 0.38** | 0.39** | 0.40** | 0.30** | 0.36** | −0.23** | −0.24** | |

| BIS-M | 0.38** | 0.37** | 0.34** | 0.33** | 0.38** | 0.36** | 0.34** | −0.21** | −0.19** | ||

| BIS-N | 0.31** | 0.23** | 0.86** | 0.32** | 0.22** | 0.31** | −0.33** | −0.32** | |||

| ALS-D | 0.85** | 0.88** | 0.81** | 0.64** | 0.80** | −0.38** | −0.39** | ||||

| ALS-H | 0.86** | 0.74** | 0.59** | 0.65** | −0.26** | −0.27** | |||||

| ALS-B | 0.81** | 0.64** | 0.78** | −0.38** | −0.38** | ||||||

| ALS-X | 0.72** | 0.83** | −0.43** | −0.40** | |||||||

| ALS-A | 0.62** | −0.38** | −0.28** | ||||||||

| ALSX/D | −0.44** | −0.45** | |||||||||

| GAF | 0.49** |

Note. IMT = Immediate Memory Task; BIS = Barratt Impulsivity Scale; BIS-A = BIS Attentional Impulsivity scale; BIS-M = BIS Motor Impulsivity scale; BIS-N = BIS Nonplanning Impulsivity scale; ALS = Affective Lability Scale; ALS-D = ALS Depression scale; ALS-H = ALS Hypomania scale; ALS-B = ALS Biphasic scale; ALS-X = ALS Anxiety scale; ALS-A = ALS Anger scale; AL-X/D = AL Anxiety/Depression scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; Q-LES-Q = Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Demographic Variables (Table 3)

Table 3.

Demographic Variables as a function of Diagnostic Group (N = 302)

| Diagnostic Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IED-V (n = 41) |

IED-P (n = 60) |

IED-B (n = 111) |

PD (n = 90) |

Total (N = 302) |

|

| Age (SD) | 38.12 (10.86) | 38.05 (8.47) | 37.90 (10.9.3) | 35.60 (8.48) | 37.27 (9.80) |

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Male | 13 (31.7%) | 37 (61.7%) | 47 (42.3%) | 37 (41.1%) | 134 (44.4%) |

| Female* a, b, c | 28 (68.3%) | 23 (38.3%) | 64 (57.7%) | 53 (58.9%) | 168 (55.6%) |

| Race (%) | |||||

| Caucasian | 20 (48.8%) | 46 (76.7%) | 58 (52.3%) | 64 71.1%) | 188 (62.3%) |

| AA | 15 (36.6%) | 8 (13.3%) | 39 (35.1%) | 2 (2.2%) | 82 (27.2%) |

| Asian | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | 6 (2.0%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (7.3%) | 3 (5.0%) | 8 (7.2%) | 3 (3.3%) | 17 (5.6%) |

| Other | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (3.6%) | 2 (2.2%) | 9 (3.0%) |

| Education | |||||

| 7th – 9th Grade | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.09%) | 1 (0.01%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Partial HS | 1 (2.4%) | 4 (6.7%) | 4 (3.6%) | 2 (2.2%) | 11 (3.6%) |

| HS | 5 (12.2%) | 7 (11.7%) | 18 (16.2%) | 10 (11.1%) | 40 (13.2%) |

| Partial College | 19 (46.3%) | 16 (26.7%) | 47 (42.3%) | 22 (24.4%) | 104 (34.4%) |

| College | 12 (29.3%) | 24 (40.0%) | 25 (22.5%) | 39 (43.3%) | 100 (33.1%) |

| Graduate Training | 4 (9.8%) | 9 (15.0%) | 16 (14.4%) | 16 (17.8%) | 45 (14.9%) |

Note AA = African American; HS = High School.

IED-B ≠ IED-P,

IED-V ≠ IED-P,

IED-P ≠PD.

p < 0.01.

The four groups did not differ in age [F(3, 301) = 1.26, p = 0.29], race [χ2(12, N = 302) = 18.79, p = 0.09], or education, [χ2(12, N = 302) = 20.65, p = 0.15]. However, the groups differed with regard to gender [χ2(3, N = 302) = 10.51, p = 0.02]. The IED-V, IED-B, and PD groups had a higher proportion of women relative to the IED-P group.

Psychopathology

As shown in Table 4, the groups differed in prevalence of (non-IED) lifetime Axis I diagnoses. Follow-up analyses showed a larger proportion of IED-V and IED-B participants met criteria for a comorbid Axis I disorder than did IED-P or PD participants. Looking at different classes of Axis I disorders, a larger proportion of IED-B participants were diagnosed with a lifetime mood disorder than all other groups. The groups also differed with respect to history of substance use disorders with the IED-P group having a greater proportion of individuals diagnosed with a substance use disorder than any other group. Lastly, the groups differed on prevalence of lifetime anxiety with a monotonic trend of IED-B > IED-V > IED-P > PD. Overall, the groups differed in mean number of (non-IED) Axis I disorders [F(3, 302) = 88.92, p < 0.001, ήp2 = 0.49] with IED-B participants having more Axis I disorders than IED-V or IED-P groups, and all IED groups having more Axis I diagnoses than the PD group.

Table 4.

Lifetime Psychopathology as a Function of Diagnostic Group (N = 302)

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IED-V (n = 41) |

IED-P (n = 60) |

IED-B (n = 111) |

PD (n = 90) |

χ2 | p-value | |

| Axis I Psychopathology | ||||||

| Any (non-IED) Axis I (% subjects) a, c | 41 (100%) | 60 (100%) | 111 (100%) | 68 (75.6%) | 55.89 | 0.001 |

| Mood Disordera, b, d | 26 (63.4%) | 28 (46.7%) | 79 (71.2%) | 40 (44.4%) | 18.21 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety Disorders a, b, c, d, e, f | 17 (41.5%) | 14 (23.3%) | 50 (45.0%) | 32 (35.6%) | 8.26 | 0.04 |

| Substance Disorders a, c, e | 19 (46.3%) | 35 (58.3%) | 52 (46.8%) | 26 (28.9%) | 13.81 | 0.003 |

| Axis II Psychopathology | ||||||

| Any Axis II (% subjects) a, b, d, e, f | 33 (80.5%) | 40 (66.7%) | 100 (90.1%) | 90 (100%) | 39.61 | 0.001 |

| Cluster Aa, d | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (1.7%) | 20 (18.0%) | 4 (4.4%) | 17.35 | 0.001 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder a, c, d, f | 11 (26.8%) | 12 (20.0%) | 40 (36.0%) | 7 (7.8%) | 25.48 | 0.001 |

| Other Cluster B a, d, f | 13 (31.7%) | 11 (18.3%) | 36 (32.4%) | 9 (10.0%) | 17.19 | 0.001 |

| Cluster C a, b, e, f | 6 (14.6%) | 9 (15.0%) | 37 (33.3%) | 30 (33.3%) | 12.47 | 0.01 |

| Not Otherwise Specifiedd, e | 13 (31.7%) | 16 (26.7%) | 29 (26.1%) | 43(47.8%) | 15.83 | 0.02 |

IED-B ≠ IED-P,

IED-B ≠ IED-V,

IED-V ≠ IED-P,

IED-B ≠ PD,

IED-P ≠PD,

IED-V ≠ PD.

Group differences were also found with respect to personality disorder prevalence (Table 4). Follow-up analyses indicated that the IED-B group had a significantly larger proportion of individuals with a PD than IED-V or IED-P groups. All IED groups had a smaller proportion of personality-disordered individuals than the PD group (which was 100%). With respect to personality disorder clusters, a larger proportion of participants in the IED-B group were diagnosed with a Cluster A disorder than in those in the IED-P and PD groups. In contrast, a higher proportion of IED-B and PD participants were diagnosed with a Cluster C disorder than participants in the IED-P or IED-V groups. Due to the relationship between borderline personality disorder (BPD) and affective aggression, we separated this diagnosis from the other cluster B disorders. A greater proportion of IED-B and IED-V participants were diagnosed with BPD relative to the IED-P or PD groups. Regarding the remaining Cluster B disorders, these were more common in the IED-B group than the IED-P or PD groups. The IED-V group also showed a higher prevalence of a non-BPD Cluster B diagnosis than the PD group. Finally, there was also a group effect for number of personality disorders [F (3, 302) = 9.97, p < 0.001, ήp2 = 0.08] with post-hoc analyses showing that the IED-B group endorsed a significantly higher number of personality disorders than the IED-P or PD groups.

Aggression

Behavioral Aggression

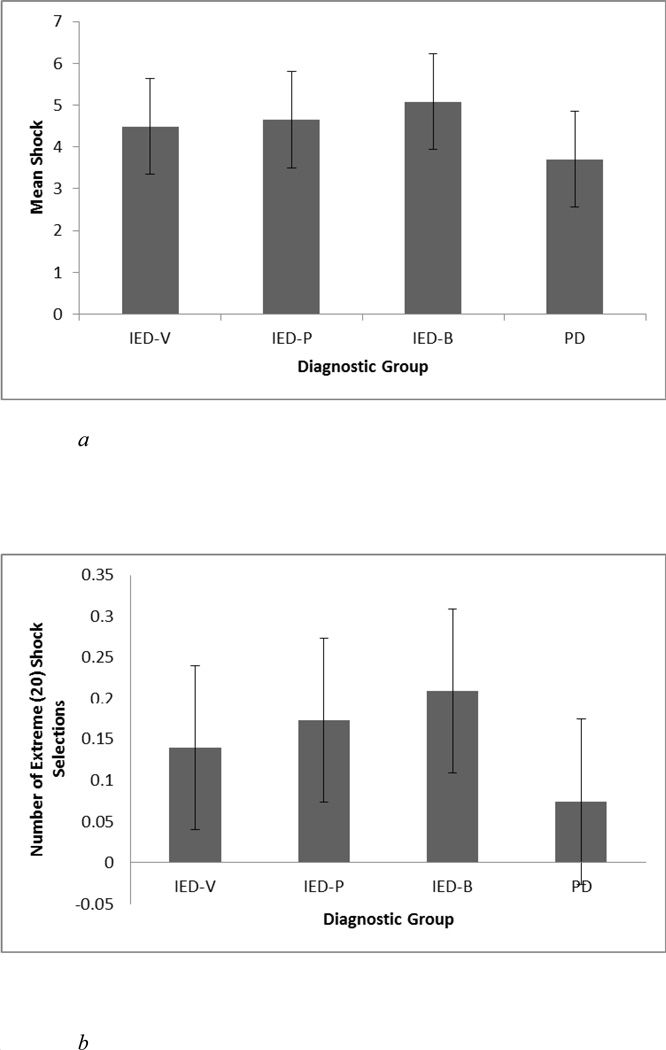

TAP 20-shocks were recoded as 11 to minimize their influence on mean shock calculations (McCloskey and Berman, 2003a). A 4 (Group)*4 (Provocation Block)*2 (Gender) repeated measures ANOVA for mean shock selection across the four blocks revealed a significant between-subjects effect for group [F(3, 256) = 4.83, p < 0.01, ήp2 = 0.05] (Figure 1a). Post-hoc analyses showed that IED-B and IED-P participants set significantly higher mean shocks than PD participants, while the IED-V participants did not differ from any other group. The effect of gender and the gender*group interaction were not significant (p’s > 0.16).

Figure 1.

a. Mean shock selections on the Taylor Aggression Paradigm as a function of diagnostic group. (n = 264)

b. Number of extreme (20) shock selections on the Taylor Aggression Paradigm as a function of diagnostic group. (n = 264)

The extreme shock (number of 20 shocks) data were positively skewed (z = 4.30). Therefore the data were log transformed, which reduced the skew to acceptable levels (z = 1.82). A 4*4*2 repeated measures ANOVA for number of extreme shocks revealed a non-significant trend for group, F(3, 256) = 2.54, p = 0.06, ήp2 = 0.03 (Figure 1b). Exploratory analyses showed that combined, all three IED groups set more extreme shocks than the PD group [F(1, 262) = 5.41, p = 0.02, ήp2 = 0.02]. The effect of gender and the gender*group interaction were not significant (p’s > 0.10).

Self-Reported Aggression and Anger (Table 5)

Table 5.

Self-Reported Aggression and Associated Dependent Variables as a Function of Diagnostic Group (N = 302)

| Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IED-V (n = 41) |

IED-P (n = 60) |

IED-B (n = 111) |

PD (n = 90) |

F value |

p-value | ήp2 | |

| BPAQ | |||||||

| Physical Aggressiond, e, f | 23.45 (8.59) | 24.23 (9.57) | 27.61 (8.96) | 16.97 (6.61) | 24.95 | 0.000 | 0.21 |

| Verbal Aggressiona, d | 15.68 (5.54) | 14.47 (3.81) | 17.68 (4.36) | 13.99 (4.02) | 13.78 | 0.000 | 0.12 |

| Angera, b, d, e, f | 20.93 (7.23) | 20.85 (6.13) | 24.78 (6.13) | 15.95 (5.99) | 33.74 | 0.000 | 0.26 |

| Hostilityd | 21.45 (7.50) | 22.76 (6.13) | 24.27 (7.53) | 21.01 (6.03) | 3.93 | 0.009 | 0.04 |

| LHA-Aa, b, d, e, f | 14.12 (4.41) | 15.48 (5.30) | 18.59 (3.97) | 8.04 (4.58) | 89.51 | 0.000 | 0.47 |

| STAXI-2 | |||||||

| Anger Control-Ina, c, d, f | 18.90 (5.93) | 19.75 (5.25) | 17.88 (4.63) | 21.74 (4.53) | 10.35 | 0.000 | 0.10 |

| Anger Control-Outa, b, d, e, f | 20.56 (5.68) | 20.60 (4.61) | 17.15 (4.50) | 23.49 (4.94) | 28.76 | 0.000 | 0.23 |

| Anger Expression-In | 18.44 (4.89) | 18.44 (4.89) | 17.87 (4.18) | 19.29 (4.87) | 18.61 (4.35) | 1.12 | 0.341 |

| Anger Expression-Outa, b, d, e, f | 19.51 (5.60) | 19.51 (5.60) | 18.37 (4.25) | 21.90 (5.34) | 15.51 (3.89) | 29.15 | 0.000 |

| IMTd | 0.37 (0.19) | 0.37 (0.19) | 0.32 (0.19) | 0.37 (0.18) | 0.29 (0.15) | 3.21 | 0.024 |

| BIS | |||||||

| Attentional | 17.46 (3.93) | 18.43 (3.28) | 18.57 (3.40) | 17.73 (3.66) | 1.74 | 0.159 | 0.02 |

| Motorb, d | 21.12 (4.43) | 22.33 (4.49) | 23.35 (5.13) | 21.32 (4.45) | 3.69 | 0.012 | 0.04 |

| Nonplanning | 26.26 (5.45) | 26.40 (5.44) | 27.45 (5.93) | 25.60 (4.93) | 1.87 | 0.135 | 0.02 |

| ALS | |||||||

| Depressiona, d | 24.10 (7.04) | 22.32 (7.08) | 25.35 (6.14) | 22.51 (5.67) | 4.29 | 0.006 | 0.04 |

| Hypomaniaa, d | 25.25 (7.86) | 23.83 (7.60) | 27.10 (6.91) | 24.37 (6.59) | 3.84 | 0.010 | 0.04 |

| Biphasica, d | 17.60 (6.07) | 16.52 (5.86) | 19.13 (6.11) | 16.30 (4.84) | 4.98 | 0.002 | 0.05 |

| Anxietya, d | 13.75 (4.90) | 12.32 (4.50) | 14.74 (4.75) | 12.02 (4.11) | 7.41 | 0.000 | 0.07 |

| Angera, d, e, f | 15.55 (5.46) | 14.20 (4.91) | 17.83 (4.98) | 11.27 (4.06) | 32.26 | 0.000 | 0.25 |

| Anxiety/Depressiona, d | 14.58 (5.30) | 14.35 (5.35) | 17.48 (6.24) | 14.27 (5.55) | 7.36 | 0.000 | 0.07 |

| GAFa, c, d, f | 57.51 (10.52) | 63.67 (10.53) | 55.62 (9.06) | 62.52 (8.49) | 12.99 | 0.000 | 0.12 |

| Q-LES-Qa, c, d, f | 42.71 (10.15) | 46.17 (10.01) | 40.70 (11.53) | 45.70 (8.11) | 6.37 | 0.000 | 0.06 |

Note. BPAQ = Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire; LHA-A = Life History of Aggression – Aggression Scale; STAXI-2 = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory; IMT = Immediate Memory Task; BIS = Barratt Impulsivity Scale; ALS = Affective Lability Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; Q-LES-Q = Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.

IED-B ≠ IED-P,

IED-B ≠ IED-V,

IED-V ≠ IED-P,

IED-B ≠ PD,

IED-P ≠PD,

IED-V ≠ PD.

A 4 (Group)*2 (Gender) MANOVA on the BPAQ scales revealed a significant multivariate effect of diagnostic group [Wilks F(12, 778.14) = 11.30, p < 0.001, ήp2 = 0.13] as well as a significant multivariate group*gender interaction [Wilks F(12, 783.43) = 2.24, p = 0.009, ήp2 = 0.03]. There was no significant multivariate effect of gender (p > 0.05). Subsequent univariate analyses revealed a significant effect of group for all four BPAQ scales. Post-hoc analyses showed that all IED groups reported significantly more physical aggression than the PD group, but did not differ from each other. With respect to verbal aggression, the participants in the IED-B group reported more verbal aggression than those in the IED-P or PD groups. For anger, all IED groups reported high trait anger than the PD group. The IED-B group also reported more anger than the IED-P and IED-V groups, who did not differ. For hostility, the IED-B group reported more hostility than the PD group. There was also a significant gender*group interaction for hostility [F(3, 301) = 4.03, p < 0.01, ήp2 = 0.04]. Follow-up simple effects analyses revealed that men in the IED-V group self-reported higher trait hostility than women [t(39) = 2.94, p = 0.005], but men in the PD group reported lower hostility than women [t(88) = −2.22, p = 0.03]. There were no gender differences in the IED-P or IED-B groups (p’s > 0.27).

A 4 (Group)*2 (Gender) ANOVA on the LHA Aggression scale revealed a significant main effect of group. Post-hoc analyses showed that the IED-B group reported more acts of aggression than the IED-V and IED-P groups who reported more acts of aggression than the PD group. Neither the main effect of gender nor the gender × group interaction was significant (F’s < 1).

A 4 (Group*2 (Gender) MANOVA on the STAXI-2 scales revealed a significant multivariate effect of group [Wilks F(12, 786.08) = 9.33, p < 0.001, ήp2 = 0.11]. There was no multivariate effect of gender or group × gender interaction, F’s < 1. Univariate analyses revealed significant group effects for AC-I, AC-O, and AX-O. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the IED-B and IED-V groups reported lower levels of AC-I than the PD group. The IED-B group also reported lower levels of AC-O and higher levels of AX-O than the IED-V and IED-P groups who reported lower levels of AC-O and higher levels of AX-O than the PD group.

Associated Constructs (Table 5)

Impulsivity

A 4 (Group)*2 (Gender) ANOVA of the IMT Ratio revealed a main effect of group. Post-hoc analyses showed that the IED-V group was more impulsive than the PD group. There was neither a main effect of gender nor a significant group × gender interaction (p’s > 0.25).

A 4 (Group)*2 (Gender) MANOVA on the BIS-11 scales revealed no significant multivariate effect of group, gender, or group × gender interaction (p’s > 0.08). Univariate analyses found a main effect of group for motor impulsivity with post-hoc analyses showing IED-B participants reported more motor impulsivity than IED-V participants. There were no differences between groups for either attentional impulsiveness or nonplanning.

Affective Lability

A 4 (Group)*2 (Gender) MANOVA on the ALS scales revealed a significant multivariate effect of group [Wilks F(18, 826.39) = 6.66, p < 0.001, ήp2 = 0.12]. There was no multivariate effect of gender or group*gender interaction (p’s > 0.14). Univariate analyses showed significant group effects for all six ALS scales. With respect to anger, all IED groups reported significantly more anger than the PD group; the IED-B group also reported more anger than the IED-P group. For all other ALS scales, the IED-B group reported significantly increased affective lability compared to both the PD and IED-P groups. No other group differences were found for depression, hypomania, biphasic, anxiety, or anxiety/depression.

Psychosocial Functioning

A 4 (Group) *2 (Gender) ANOVA on GAF scores revealed a significant main effect of group. Post-hoc analysis showed that IED-B and IED-V groups each had lower GAF scores than IED-P and PD groups. Neither the main effect of gender nor the gender*group interaction was significant (p’s > 0.15).

A 4 (Group)*2 (Gender) ANOVA on the Q-LES-Q total score revealed a significant group effect in which IED-B group reported a lower Q-LES-Q score than IED-P or PD groups. Neither the main effect of gender nor the gender*group interaction was significant (p’s > 0.15).

To assess whether the group differences in impairments were in part an artifact of differences in comorbidity, the above psychosocial functioning analyses were re-run with (a) total number of (non-IED) Axis I and Axis II comorbid diagnoses and (b) the presence of three specific disorder/classes, borderline personality disorder, mood disorder, and substance use disorder as covariates. Including these covariates did not change the pattern of results for GAF scores. For the Q-LES-Q, inclusion of covariates eliminated the significant differences between the IED-V group and both the IED-P and PD groups. However, the IED-B group continued to show significantly lower Q-LES-Q scores than either the IED-P or PD groups.

4. Discussion

The current study examined levels of anger and aggression as well as associated cognitive-affective deficits and psychosocial functioning in three groups of individuals who met DSM-5 criteria for IED based on (1) only verbal aggression (IED-V), (2) only physical (IED-P), or (3) both verbal and physical aggression (IED-B) as well as a non-IED personality-disordered (PD) comparison group. It was hypothesized that all three IED groups would differ from the PD control group on measures of anger, anger dyscontrol, and aggression but that the IED groups would only differ from each other on measures specific to verbal and physical aggression. It was also hypothesized that each IED group would show greater deficits on putative constructs of affective lability and impulsivity, as well as poorer psychosocial functioning, relative to the PD control group. The IED groups were not expected to differ on these measures. Results from the current study are mixed and suggest that pathological verbal aggression may be as problematic as pathological physical aggression, and those individuals who engage in both forms of pathological aggression may be the most impaired.

As predicted, the IED groups showed increased anger and aggression relative to PD participants. The IED groups self-reported higher trait anger and physical aggression as well as more aggressive acts, less control of angry feelings, and greater anger expression than the PD group. Likewise, on a behavioral aggression measure, all IED groups set more extreme shocks than the PD group and the IED-B and IED-P groups set higher mean shocks than the PD group. Overall, these findings are consistent with previous research showing increased anger and aggression in individuals with IED relative to psychiatric controls (Coccaro et al., 1998; Coccaro, 2003; Coccaro et al., 2005; McCloskey et al., 2006; Coccaro, 2011).

There was limited support for the hypothesis that the IED groups would differ in levels of aggression that specifically target either verbal or physical aggression. The IED-V, IED–P, and IED-B groups all reported similar levels of trait physical aggression. However, the IED-B group reported more trait verbal aggression than did the IED-P group. Contrary to the hypothesis, the IED-V and IED-P groups did not differ with respect to self-reported physical or verbal aggression. Moreover, on the behavioral measure of physical aggression, all IED groups were comparably aggressive. These results suggest that individuals who engaged in one form of aggression report comparable overall trait propensity toward aggressive behavior regardless of type of aggressive act. Individuals who report participating in both verbal and physically aggressive acts also report significantly elevated trait aggression.

Additionally, it was hypothesized that all three IED groups would show comparable levels of trait anger dyscontrol and overall aggression. This hypothesis was not supported. The only anger/aggression scales where there were no differences between groups were trait hostility and internal anger suppression. The IED-B group endorsed more frequent aggressive acts, higher trait anger, higher levels of outward anger expression, and poorer control of outward anger expression than the other two IED groups. The IED-B group also reported lower levels of control of suppressed angry feelings than IED-P (but not IED-V) participants. The finding that individuals who engage in both clinically significant verbal and physical aggression also evidence greater deficits in anger and aggression is somewhat consistent with previous research. Coccaro (2011) concluded that individuals who met diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV IED (i.e., only physical aggression) reported a similar number of aggressive acts on the LHA as individuals without IED, while individuals who met research criteria for IED-IR (i.e., both verbal and physical aggression were possible) reported a significantly higher number of aggressive acts. However, McCloskey and colleagues (2008a) found no group differences on the constructs of anger and anger dyscontrol using similar diagnostic groupings. It should be noted, however, that the verbal aggression group in McCloskey et al. (2008a) reported nearly identical mean levels of trait anger and anger dyscontrol as in the current study. This was also the case for the group who reported engaging in both physical and verbal aggression. Thus, it is possible that the conflicting results may be explained by the increased sample size and power to detect group differences in the current study. However, additional studies that include a larger sample of IED-V, IED-P, and IED-B individuals are needed to corroborate and expand the current findings.

Although there were clear and consistent differences between all IED groups and the PD group in terms of anger and aggression, group differences on measures of affective lability, impulsivity, psychosocial functioning were more varied. With respect to affect lability, anger was the only scale in which all IED groups showed greater dysregulation than the PD group. For all other forms of lability (i.e., depression, hypomania, biphasic, anxiety, and anxiety/depression), a consistent pattern emerged in which the IED-B group reported greater lability than the PD group as well as greater lability than the IED-P group. The IED-V and IED-P groups did not differ in any category. These findings replicate and extend previous research indicating greater non-anger affect lability in IED-B participants relative to IED-V or IED-P participants (McCloskey et al., 2008a). Moreover, the fact that the IED–B group showed the most generalized pattern of affect dysregulation provides further support for the proposed hypothesis that greater global deficits in affective lability may be associated with increased aggressive behavior.

Differences in impulsivity between diagnostic groups were also consistent with the trend of increased cognitive-affective deficits in those who engage in both verbal and physical aggression. Scores on a self-report measure of impulsivity [which were consistent with previous studies of impulsivity in IED (Lejoyeux et al., 1998; McCloskey et al., 2008a; Coccaro, 2011)], showed the IED-B group reported greater motoric impulsivity than did the IED-V group; there were no other differences among IED groups on either self-reported or behavioral measures of impulsivity. The IED-B group also self-reported greater motoric impulsivity than the PD group and showed greater behavioral impulsivity than PD controls. There were no other differences between diagnostic groups in behavioral impulsivity, which mirrors previous research showing an ephemeral relationship between impulsivity and IED (Coccaro et al., 1998; McCloskey et al., 2008a; Coccaro, 2011). In fact, it has been suggested that it is not the level of generalized impulsivity that differentiates individuals with IED from those without, but the impulsive nature of the aggressive outbursts specifically (Coccaro, 2011).

With respect to psychosocial functioning, the IED-B and IED-V groups showed poorer quality of life and greater psychosocial impairment compared to IED-P and PD groups. For IED-B this was true even when controlling for comorbid Axis I and Axis II psychopathology whereas the inclusion of these covariates eliminated the IED-V group differences for self-reported quality of life. Thus, the clear pattern of affect regulation and behavioral control deficits in IED-B relative to PD is again reflected in impaired psychosocial functioning and furthers the argument that the presence of both verbal and physical aggression may be indicative of a particularly severe subgroup of individuals with IED. It reasons that individuals who show increased difficulty controlling angry outbursts, greater overall affect dysregulation, and a high number of aggressive acts would also show substantial distress, occupational difficulty, difficulty maintaining relationships, and legal problems (McElroy et al., 1998; McCloskey et al., 2006; McCloskey et al., 2008a; Ortega et al., 2008). Thus, it’s possible that the inability to regulate affect, particularly angry affect, is a core contributor to the overall dysfunction and psychosocial impairment seen in the IED-B group.

The finding that the IED-B group reported greater psychosocial impairment than the IED-P group combined with the finding that the IED-V group was seen as more impaired by clinicians than IED-P or PD groups provides some evidence that frequent verbal aggression may be more deleterious to psychosocial functioning than occasional physical aggression. This is generally consistent with previous research (e.g., Coccaro et al., 1998; McCloskey et al., 2008a). However, after controlling for psychopathology, IED-V participants did not differ from IED-P or PD groups on self-reported quality of life. Thus, the extent to which verbal aggression in the absence of physical aggression impairs one’s experienced life circumstance remains unclear.

This investigation represents the first study to specifically compare a group of aggressive individuals who engage in pathological levels of verbal (but not physical) aggression to a group of individuals who engage in pathological levels of physical (but not verbal) aggression as well as to those who engage in both pathological verbal and physical aggression. The current study also allowed for investigation of the diagnostic validity of pathological verbal aggression and made it possible to examine areas of increased cognitive-affective deficits and psychosocial impairment in three different sub-types of individuals diagnosed with IED. The study also used a multi-modal assessment of aggression and impulsivity as well as both clinician-assessed and self-report measures of psychosocial functioning. This allowed for more complex investigation of pathological verbal aggression as well as the putative constructs of IED.

Although this study represents the largest investigation of verbal vs. physical sub-types of IED to date, the number of individuals in the IED-V and IED-P groups were relatively small (n = 41 and n = 60, respectively). Future investigations should attempt to replicate the current findings using a larger sample that may be better powered to detect group differences. Additionally, despite a general approach to recruiting participants from the community that included newspaper, radio, and Craigslist advertisements, a high number of participants in the current study reported having at least a college education (48%). This percentage is somewhat higher than the national average of 30% (United States Census Bureau, 2012) and may affect generalizability of the current findings. This also suggests that despite the many adverse consequences of IED, some aspects of ability to function in the community (i.e., ability to get an education) may remain relatively intact (Kessler et al, 2006).

Future studies may want to selectively recruit for non-college educated participants for greater generalizability and assessment of functional impairment. Moreover, despite the use of multiple measures of impulsivity, the current study may not have adequately captured the broad, heterogeneity of this construct. Given the inconsistent relationship between impulsivity and IED, future investigations should consider using a more comprehensive measure of impulsivity that taps into different facets of impulsivity (Whiteside and Lynam, 2001). Lastly, the current study employed a multi-modal approach to investigating aggression, impulsivity, and psychosocial functioning, but used only a self-report measure of affective lability. Future studies should include clinician-assessed or behavioral tasks of affective lability to further elucidate the relationship between affect dysregulation and pathological verbal aggression.

Taken together, the current findings support and extend previous research showing that the levels of verbal aggression used in the DSM-5 criteria are associated with anger, aggression and psychosocial impairment above that of individuals with Axis II psychopathology and equivalent to (and sometimes greater than) individuals meeting IED criteria on the basis of physical outbursts. The current study also suggests that individuals who engage in both forms of aggression may represent a more severe, more impaired subgroup within IED; they show increased trait anger, anger dysregulation, and a higher number of aggressive acts compared to individuals who engage in a single form of aggression (verbal or physical aggression) as well as global deficits in affective lability and psychosocial impairment. Overall, the current study highlights the clinical significance of frequent verbal aggression and suggests the possibility of a unique, and more severe, profile of even greater deficits in cognitive and affective control for individuals who engage in both frequent verbal arguments and pathological physical aggression.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Averill JR. Studies on anger and aggression. Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist. 1983;38(11):1145–1160. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.38.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validating of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best M, Williams JM, Coccaro EF. Evidence for a dysfunctional prefrontal circuit in patients with an impulsive aggressive disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(12):8448–8453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112604099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder. In: Coccaro EF, editor. Aggression: Psychiatric Assessment and Treatment. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2003. pp. 149–199. [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder interview: Validity and reliability. 2005 Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder: development of integrated research criteria for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011;52:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder as a disorder of impulsive aggression for DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:577–588. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Berman ME, Kavoussi RJ. Assessment of life history of aggression: Development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Research. 1997;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Harvey PD, Kupsaw LE, Herbert JL, Bernstein DP. American Psychiatric Association. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Overt Aggression Scale Modified [OAS M]. American Psychiatric Association Task Force for the Handbook of Psychiatric Measures; pp. 699–702. [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ. Fluoxetine and impulsive aggressive behavior in personality disorder subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1081–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ, Berman ME, Lish JD. Intermittent explosive disorder-revised: development, reliability, and validity of research criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39:368–376. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Prevalence and features of intermittent explosive disorder in a clinical setting. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1221–1227. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation – A possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–594. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Marsh DM. Neurobehavioral Research Laboratory and Clinic. Houston, TX: University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; 2003. Immediate and delayed memory tasks (IMT/ DMT 2.0): A research tool for studying attention, memory, and impulsive behavior [manual] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Marsh-Richards DM, Hatzis ES, Nouvion SO, Mathias CW. A test of alcohol dose effects on multiple behavioral measures of impulsivity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden J. Impulsivity: A discussion of clinical and experimental findings. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1999;13:180–192. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Godard J, Grondin S, Baruch P, Lafleur M. Psychosocial and neurocognitive profiles in depressed patients with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2011;190(2–3):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Greenberg BR, Serper MR. The affective lability scales: Development, reliability, and validity. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1989;45(5):786–793. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198909)45:5<786::aid-jclp2270450515>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Coccaro EF, Fava M, Jaeger S, Jin R, Walters E. The prevalence and correlates of Intermittent Explosive Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:669–678. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HS, Ferro T, Riso LP. Test–retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of axis I and II disorders in a family study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1043–1047. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Ziwi AB, Lozano R, editors. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Lejoyeux M, Feuché N, Loi S, Soloman J, Adès J. Impulse-control disorders in alcoholics are related to sensation seeking and not to impulsivity. Psychiatry Research. 1998;81(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey M, Berman M. Alcohol intoxication and self-aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003a;112:306–311. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey M, Berman ME. Laboratory measures of aggression: The Taylor Aggression Paradigm. In: Coccaro EF, editor. Aggression: Assessment and Treatment into the 21st Century. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2003b. pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, Berman ME, Noblett KL, Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder-integrated research diagnostic criteria: convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, Kleabir K, Berman ME, Chen EY, Coccaro EF. Unhealthy aggression: Intermittent explosive disorder and adverse physical health outcomes. Health Psychology. 2010;29(3):324–332. doi: 10.1037/a0019072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, Lee R, Berman ME, Noblett KL, Coccaro EF. The relationship between impulsive verbal aggression and intermittent explosive disorder. Aggressive Behavior. 2008a;34:51–60. doi: 10.1002/ab.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, Noblett KL, Deffenbacher JL, Gollan JK, Coccaro EF. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for intermittent explosive disorder: A pilot randomized clinical sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008b;76(5):876–886. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Soutullo CA, Beckman DA, Taylor P, Jr, Keck PE., Jr DSM–IV Intermittent Explosive Disorder: A report of 27 cases. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:203–210. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Canino G, Alegria M. Lifetime and 12-month intermittent explosive disorder in Latinos. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;78:133–139. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman N. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Salari SM, Baldwin BM. Verbal, physical, and injurious aggression among intimate couples over time. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:523–550. [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:429–442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2): Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP. Aggressive behavior and physiological arousal as a function of provocation and the tendency to inhibit aggression. Journal of Personality. 1967;35:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Educational attainment by race and hispanic origin: 1970 to 2010. 2012:151. Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/12statab/educ.pdf.

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. Understanding the role of impulsivity and externalizing psychopathology in alcohol abuse: Application of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale. Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 2003;11:210–217. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Bradford Reich D, Fitzmaurice G. The 10-year course of psychosocial functioning among patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;122(2):103–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]