Abstract

No research with youth has investigated whether measured genetic risk interacts with stressful environment (GxE) to explain engagement in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Two independent samples of youth were used to test the a priori hypothesis that the Transporter-Linked Polymorphic Region (5-HTTLPR) would interact with chronic interpersonal stress to predict NSSI. We tested this hypothesis with children and adolescents from United States public schools in two independent samples (N’s = 300 and 271) using identical procedures and methods. They were interviewed in person with the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview to assess NSSI engagement and with the UCLA Chronic Stress Interview to assess interpersonal stress. Buccal cells were collected for genotyping of 5-HTTLPR. For both samples, ANOVAs revealed the hypothesized G*E. Specifically, short carriers who experienced severe interpersonal stress exhibited the highest level of NSSI engagement. Replicated across two independent samples, results provide the first demonstration that youth at high genetic susceptibility (5-HTTLPR) and high environmental exposure (chronic interpersonal stress) are at heightened risk for NSSI.

Keywords: NSSI, G*E, interpersonal stress, youth

1. Introduction

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as intentionally causing bodily harm to oneself without the intent to die (Nock and Favazza, 2009). In community samples, approximately 8% of early adolescents report engaging in NSSI behavior, and this rate increases in middle to late adolescents (13.9-21.4%; Barrocas et al., 2010). Research with clinical samples shows even higher rates, with about 40% of adolescent inpatients engaging in NSSI (Barrocas et al., 2010). This study is the first to examine whether functional variation in the Transporter-Linked Polymorphic Region (5-HTTLPR) in the regulatory region of the gene SLC6A4, that codes for the serotonin transporter, moderated the effect of interpersonal stress on NSSI among youth.

NSSI models posit a vulnerability-stress model that emphasizes interpersonal stressors (Prinstein, Guerry, Browne, et al., 2009). Yet, no work has examined measured genetic risk, as the vulnerability, enhancing the effect of interpersonal stress for explaining NSSI. Here, we focus on 5-HTTLPR because it is associated with several traits related to NSSI behaviors, including emotion regulation and behavior control problems (Canli and Lesch, 2007) and suicidal behaviors (Mann, Brent, and Arango, 2001).

Polymorphisms of the 5HT system are candidates of interest and biologically plausible for testing G*E effects on NSSI given 5HT’s involvement in emotion and cognition (Canli and Lesch, 2007). The serotonin transporter regulates serotonin function by terminating serotonin action in the synapse via reuptake. The short (S) allele is associated with decreased transcriptional efficiency compared with the long (L) allele (Canli and Lesch, 2007). The decreased transcriptional efficiency associated with the S allele results in less serotonin being recaptured in the presynaptic neuron when compared to the L allele. Although the exact mechanism by which this polymorphism gives rise to psychiatric outcomes, including NSSI, has not been fully elucidated, there have been many studies investigating its role in phenotypes that correlate strongly with NSSI, including depression (see positive meta analysis by Karg, Burmeister, Shedden, & Sen, 2011, although there is controversy as seen in negative meta analysis by Risch and colleagues, 2009) and related emotional distress outcomes, such as borderline personality disordered traits (Hankin, Barrocas et al., 2011).

This study incorporated two suggestions from the G*E literature to provide a more accurate and rigorous examination of G*E in NSSI. First is using reliable and valid assessments of environmental stress (Uher and McGuffin, 2010). We used the gold-standard stress interview to assess for interpersonal stress (Hammen, Adrian, Gordon, et al., 1987). Second, we used a built-in replication sample to enhance confidence about significant G*E effects and reduce false positive concerns (Duncan and Keller, 2011). This study reports data from two independent samples in which identical methods and procedures were used; the second sample provides opportunity to replicate the expected significant G*E effect for explaining NSSI risk.

We tested the a priori hypothesis that youth with at least one short allele of 5-HTTLPR, and who experience greater chronic interpersonal stress, would report higher NSSI compared to those with low interpersonal stress or LL genotype group regardless of stress level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study 1

2.1.1 Sample and Procedures

A general, community sample of 300 youth (mean age=12.0; SD=2.45; 55% girls; 32% 3rd grade, 36% 6th grade, and 32% 9th grade; 67% Caucasian, 7% African-American, 7% Hispanic, 4% Asian-American, and 14% mixed ethnicity) was recruited from schools in Colorado. Eligibility was based on the child being in 3rd, 6th, or 9th grade in participating schools. Inclusion criteria consisted of English-fluency; exclusion criteria included children with IQ>70, an autism spectrum or psychotic disorder (see Barrocas et al., 2012 for cohort study details). Youth visited the lab with a caretaker, who provided informed consent for their child; youth assented to participation. The University of Denver’s Institutional Research Board (IRB) approved the study at this site.

2.1.2 Measures

2.1.2.1 NSSI

NSSI was measured using the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI; Nock, Holmberg, Photos, et al., 2007), a structured clinical interview assessing presence and frequency of NSSI engagement. For this study, endorsement of NSSI engagement was scored in a dichotomous manner, such that youth who met criteria for NSSI were scored as “1” and those who denied NSSI were rated as “0”. Interviews were conducted in person. SITBI has excellent inter-rater and test-retest reliability (κs = 1.00) and validity (κs ≥ 0.74). Inter-rater reliability for SITBI in this study was excellent (κ = 1.00).

2.1.2.2 Chronic Interpersonal Stress

The youth version of the UCLA Chronic Stress Interview (CSI; Hammen, et al., 1987), a semi-structured contextual stress interview, assessed stress. Interviews were conducted over the phone. CSI has excellent reliability and validity. Peer and romantic domains were used to create an index for chronic interpersonal peer stress. Information on peer and romantic stress were presented to a team of blind raters who arrived at a severity score ranging from 1 (little/no stress) to 5 (severe stress) and a chronicity score from 1 (less than 6 months) to 5 (5 years or more). These scores were combined and then recoded (0 to 2) to designate no-average (0), moderate (1), and severe (2) amounts of chronic interpersonal stress.

2.1.2.3 Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981) is the most commonly used self-report measure assessing depressive symptoms among youth. It shows good reliability (alpha = 0.89 in this study) and validity.

2.2 Study 2

2.2.1 Sample and Procedures

Participants included 271 youth (mean age=11.7, SD=2.47; 54% girls; 30% 3rd grade, 36% 6th grade, and 34% 9th grades; 56% Caucasian, 16% African-American, 8% Hispanic, 16% Asian-American, and 4% mixed ethnicity) who were recruited from schools in the general community in New Jersey. Procedures and measures were identical to Study 1. Rutgers University’s IRB approved this study for this site.

2.3 Genotyping for Both Studies

Children provided a saliva sample for DNA collection via Oragene® kits from DNA Genotek (Ottawa, ON, Canada). 5-HTLPR alleles, including SNP rs25531, were characterized from genomic DNA isolated using standard methods (Whisman, Richardson, and Smolen, 2011). The laboratory methods, including storage of DNA and genotyping methods, are reported in Whisman 2011. Genotyping was performed on all participants, and this resulted in a successful 98% call rate.

Both bi-allelic and tri-allelic genotypes were determined in order to take into account the potential effects of rs25531 on 5-HTTLPR functioning (Hu, Oroszi, Chun, et al. 2005). The results of the analyses were the same for both approaches.

An additive genetic model was used, so three genotype groups of participants were formed. The bi-allelic Genotype N’s for Study 1 were SS=67, SL=135, LL=98; tri-allelic N’s were SS/SLg/LgLg=84, S/La/La/Lg=141, and La/La=75. Genotype groups did not vary significantly by race (χ2 (1, N = 300)= 0.38, P = 0.54) or sex (χ2 (1, N = 300)= 0.001, P = 0.97). Bi-allelic genotype N’s for Study 2 were SS=56, SL=136, LL=79; tri-allelic N’s were SS/SLg/LgLg=81, S/La/La/Lg=138, and La/La=52. Genotype groups did not vary significantly by race (Caucasian compared to non-Caucasian; χ2 (1, N = 271) = 0.47, P = 0.49) or sex (χ2 (1, N = 271) = 0.02, P = 0.87). Genotype groups did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

2.4 Data Analytic Plan

A 3×3 (Interpersonal Stress by 5-HTTLPR genotype) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with NSSI as dependent variable was used to test the primary hypothesis. Initial inspection revealed that the data did not meet assumptions of normality, so a square root transformation was used that then exhibited normal distributions for each variable. Accordingly, the data were then appropriate for analysis by ANOVA. Missing data were listwise deleted. There was no familial relatedness among participants (i.e., no siblings were used in analyses), so no correction for relatedness was used.

In initial model testing, we examined whether child gender or grade moderated effects. Neither significantly moderated the expected G*E: gender [F(1, 570) = 1.49, p = 0.22] nor grade [F(2, 570) = 1.45, p = 0.17]. However, given demonstrated gender (9% girls vs 6.7% boys) and age effects in NSSI rates (Barrocas et al., 2012), we retained gender and grade as covariates along with CDI and ethnicity.

Self-reported ethnicity was included as covariate to manage concerns about ethnic population stratification because self-reported ethnicity correlates nearly perfectly with genetic ancestry and addresses concerns about population stratification (Tang, Quertermous, Rodriguez, et al., 2005). CDI was included as a control because substantial prior evidence (e.g., Karg et al, 2011), including data from our laboratory (e.g., Ford, Mauss, Troy, Smolen, and Hankin, in press; Hankin, Jenness, et al., 2010; Jenness, Hankin, Abela, Young, and Smolen, 2011; Oppenheimer et al., 2013), shows that 5-HTTLPR interacts with stress, and other psychosocial/environmental influences, to predict depressive symptoms. We wanted to examine the hypothesized unique effect of 5-HTTLPR*interpersonal stress in explaining variance for NSSI after removing the effect of depressive symptoms, which is strongly associated with NSSI.

We hypothesized that 5-HTTLPR genotype would interact with interpersonal stress to account for significant variance in NSSI. We tested this first separately for each sample from Denver and Rutgers: Denver was the discovery sample, and Rutgers served as the independent replication sample; then we combined both samples to have a larger sample size. We planned follow-up comparisons to deconstruct the expected G*E with analyses comparing genotype group (e.g., LL, SL, and SS using bi-allelic approach) within each interpersonal stress category to see which genotype was significantly different at each level of interpersonal stress.

3. Results

3.1 Preliminary Descriptive Results

In total, 8.6% of the whole sample reported NSSI engagement; this included 6% of LL, 8% of SL, and 10.7% of SS genotype groups. There was no significant rGE in either Study 1 (r = 0.02, P = 0.76) or 2 (r = 0.07, P = 0.21).

3.2. G*E Results by Site to Demonstrate Replication

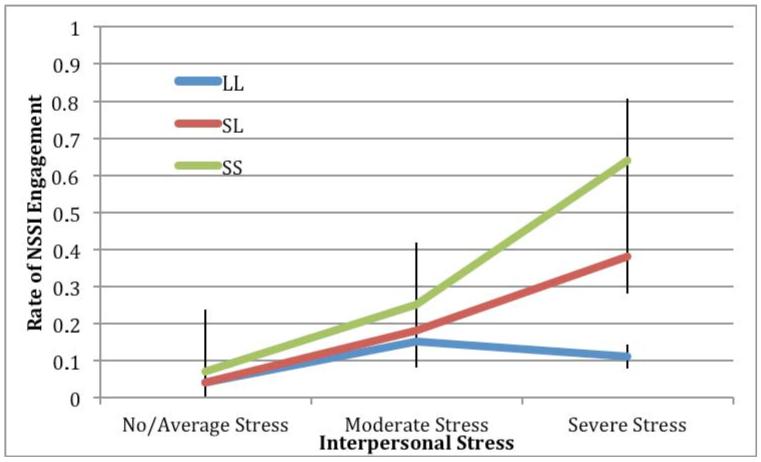

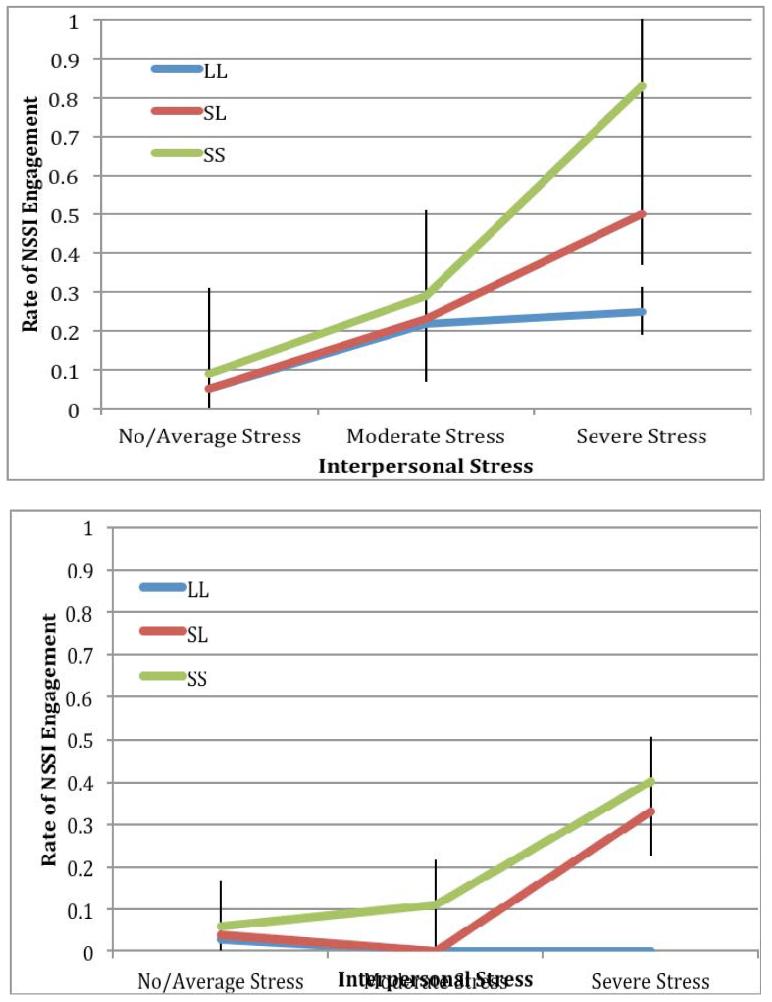

Analyses showed the significant G*E effect was obtained in both samples (see Supplementary Table 1 for bi-allelic results; Supplementary Table 2 for tri-allelic results). The interaction of bi-allelic 5-HTTLPR x interpersonal stress was significant in Study 1 [F(4, 299) = 2.96, p = 0.02, Partial Eta squared = .03] and Study 2: [F(4, 270) = 2.81, p = 0.02, Partial Eta squared = .03]. Planned follow-up analyses showed that among youth with severe chronic interpersonal stress, SS and SL genotypes differed significantly from the LL group in Study 1, F(2, 15) = 4.12 p < 0.05; in Study 2, SS and SL genotypes differed from the LL group F(2, 13) = 4.20 p < 0.05. There was no difference between genotype groups in the no-average (Study 1, F(2, 250) =0 .82, p = 0.44; Study 2, F(2,226) = 0.39, p = 0.67) or moderate stress (Study 1, F(2, 31) = .10, p = 0.90; Study 2, F(2, 30) = 0.47, p = 0.63) groups. Figure 1 illustrates these results for each sample separately (Denver, middle; Rutgers, bottom).

Figure 1.

Interaction of bi-allelic 5-HTTLPR with Chronic Interpersonal Stress for NSSI Engagement. 5-HTTLPR: serotonin transporter gene promotor polymorphism. LL: long-long allele; SL: short-long allele; SS: short-short allele. Standard deviation bars are included. (top panel is both sites combined, middle panel is Denver site; bottom panel is Rutgers site).

3.3. G*E Results for Whole Sample

Given that results were significant for each sample, we combined them together with both samples combined to illustrate the findings with the largest possible sample size. The following variables were significant factors accounting for variance in SITBI NSSI: CDI covariate [F(1, 570) = 29.56, p < 0.001, Partial Eta squared = .06], 5-HTTLPR [F(2, 570) = 8.02, p < 0.001, Partial Eta squared = .03], interpersonal stress [F(2, 570) = 14.62, p < 0.001, Partial Eta squared = .06], and the interaction of bi-allelic 5-HTTLPR x interpersonal stress [F(4, 570) = 4.03, p = 0.003, Partial Eta squared = .03]. Planned follow-up analyses showed that among youth with severe chronic interpersonal stress, SS and SL genotypes differed from the LL group, F(2, 29) = 4.02 p < 0.05. There was no difference between genotype groups in the no-average (F(2, 477) = 1.14, p = 0.32) or moderate stress (F(2, 62) = .25, p = 0.78) groups. Figure 1 illustrates these results for both samples combined together (top panel) with standard deviation bars. For the LL genotype, 135 were no/low stress, 29 moderate stress, and 9 severe stress; for SL it was 241 no/low, 24 moderate, 13 severe; and for SS 102 no/low, 10 moderate, and 8 severe. Finally, the interaction of tri-allelic 5-HTTLPR x interpersonal stress [F(4, 570) = 2.65, p = 0.03, Partial Eta squared = .02] was similarly significant and revealed the same pattern as bi-allelic 5-HTTLPR.

3.4. G*E Results for Caucasian only Sub-Sample

These findings were the same when only Caucasians as the predominant ethnic group were analyzed. Specifically and consistent with the trends found for the overall larger sample, factors accounting for variance in SITBI NSSI included: bi-allelic 5-HTTLPR [F(2, 312) = 4.47, p = 0.01, Partial Eta squared = .05], interpersonal stress [F(2, 312) = 9.98, p < 0.001, Partial Eta squared = .10], and the interaction of 5-HTTLPR x interpersonal stress [F(4, 312) = 5.54, p = 0.001, Partial Eta squared = .08]. Similarly, the interaction of tri-allelic 5-HTTLPR x interpersonal stress [F(4, 312) = 4.71, p = 0.001, Partial Eta squared = .09] was significant.

4. Discussion

Youth who engaged in NSSI were significantly more likely to have experienced severe chronic interpersonal stress, and 5-HTTLPR genotype affected this association. Specifically, youth who carried at least one short allele of 5-HTTLPR and who experienced significant interpersonal stress were the most likely to have engaged in NSSI. Prior theory and data suggest a general vulnerability-stress model can explain NSSI. Our findings are consistent with this perspective and show for the first time that a genetic vulnerability-stress model is obtained for NSSI among youth. The data suggest that significant variance in youth engagement in NSSI can be accounted for by the interaction of 5-HTTLPR and chronic interpersonal stress.

Study strengths enhance confidence in findings. First, we demonstrated measured G*E with NSSI among a cohort of youth recruited from the general community. As such, these findings are most generalizable to typically developing children and adolescents. Second, significant G*E effects were replicated in an independent sample using the same procedures and methods, including the gold-standard contextual stress interview to ascertain interpersonal stress.

Limitations provide directions for future research. First, the study was cross-sectional. G*E effects need to be examined longitudinally to predict prospective NSSI. Second, we used self-reported ethnicity and race to control for potential ethnic population stratification concerns, as we did not have genetically based ancestry biological markers to use as controls. Third, although G*E results were obtained in both the independent and replication samples as well as the combined larger sample, the relatively low base rate of NSSI, especially in context of an interaction effect with relatively low severe interpersonal stress and in different genotype groups, means that the findings should be interpreted cautiously and conclusions considered as preliminary until additional research with larger sample sizes can further examine this important G*E effect. Fourth, we only examined one candidate gene and one negative environmental context in this study. Finally, mechanisms underlying this G*E are unknown.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examine for the first time whether genetic risk affects the link between chronic interpersonal stress and nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) in youth.

We tested this G*E with a discovery sample and then an independent replication sample.

Youth with severe interpersonal stress and who have at least one short allele of 5- HTTLPR showed the highest level of NSSI.

Data support a genetic vulnerability-stress model of NSSI in youth.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIMH grants MH077195 (Hankin) and MH077178 (Young). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barrocas AL, Jenness JL, Davis TS, Oppenheimer CW, Technow JR, Gulley LD, Badanes LS, Hankin BL. Developmental perspectives on vulnerability for non-suicidal self-injury in youth. In: Benson J, editor. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. Vol. 40. Elsevier; London: 2010. pp. 301–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrocas A, Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JRZ. Rates of non-suicidal self-injury in youth: Age, gender, and behavioral methods in a general community sample. Pediatrics. 2012;130:39–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by- environment interaction research in psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1041–1049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford BQ, Mauss IB, Troy AS, Smolen A, Hankin BL. Emotion regulation protects children from risk associated with the 5-HTT gene and stress. Emotion. doi: 10.1037/a0036835. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Adrian C, Gordon D, Burge D, Jaenicke C, Hiroto D. Children of depressed mothers: Maternal strain and symptom predictors of dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:190–198. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Barrocas AL, Jenness J, Oppenheimer C, Badanes LS, Abela JRZ, Smolen A. Association between 5HTTLPR and borderline personality disorder traits among youth. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Oroszi G, Chun J, Smith TL, Goldman D, Schuckit MA. An expanded evaluation of the relationship of four alleles to the level of response to alcohol and the alcoholism risk. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:8–16. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150008.68473.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness J, Hankin BL, Abela JRZ, Young JF, Smolen A. Chronic family stress interacts with 5-HTTLPR to predict prospective depressive symptoms among youth. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:1074–1080. doi: 10.1002/da.20904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5- HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:444–454. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Brent DA, Arango V. The neurobiology and genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: A focus on the serotonergic system. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:467–477. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Favazza AR. Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definitions and classification. In: Nock MK, editor. Understanding Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: Origins, Assessment, and Treatment. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-Injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer CW, Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JRZ, Smolen A. Youth Genetic Vulnerability to Maternal Depressive Symptoms: 5-HTTLPR as Moderator of Intergenerational Transmission Effects in a Multiwave Prospective Study. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30:190–196. doi: 10.1002/da.22056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Guerry JD, Browne CB, Rancourt D. Interpersonal models of nonsuicidal self-injury. In Nock, M.K. (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang KY, Eaves L, Hoh J, Merikangas KR. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SL, Zhu X, Brown A, Rishch NJ. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:268–275. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15:18–22. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Richardson ED, Smolen A. Behavioral inhibition and triallelic genotyping of the serotonin transporter promoter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism. Journal of Research of Personality. 2011;45:706–709. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.