Abstract

The phospholipase D (PLD) superfamily catalyzes the hydrolysis of cell membrane phospholipids generating the key intracellular lipid second messenger phosphatidic acid. However, there is not yet any resolved structure either from a crystallized protein or from NMR of any mammalian PLDs. We propose here a 3D model of the PLD2 by combining homology and ab initio 3 dimensional structural modeling methods, and docking conformation. This model is in agreement with the biochemical and physiological behavior of PLD in cells. For the lipase activity, the N- and C-terminal histidines of the HKD motifs (His 442/His 756) form a catalytic pocket, which accommodates phosphatidylcholine head group (but not phosphatidylethanolamine or phosphatidyl serine). The model explains the mechanism of the reaction catalysis, with nucleophilic attacks of His 442 and water, the latter aided by His 756. Further, the secondary structure regions superimposed with bacterial PLD crystal structure, which indicated an agreement structure model obtained. It also explains protein-protein interactions, such as PLD2-Rac2 transmodulation (with a 1:2 stoichiometry), PLD2 GEF activity on Rac2 that is relevant for actin polymerization and cell migration, and a biding site for phosphoinositides. Since tumor-aggravating properties have been found in mice overexpressing PLD2 enzyme, the 3D model of PLD2 will be also useful, to a large extent, in developing pharmaceuticals to modulate its in vivo activity.

Keywords: Enzyme catalysis, PLD, phospholipids, homology, ab initio 3 dimensional structural modeling, docking conformation

INTRODUCTION

PLD has been associated with a variety of physiological cellular functions, such as intracellular protein trafficking, cytoskeletal dynamics, membrane remodeling and cell proliferation (1,2) and with pathological activities such as angiogenesis and tumorigenesis (3,4). There are currently 6 mammalian isoforms of the gene (PLD1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) (5–8). Out of these, PLD1 has been extensively studied. The PLD1 gene has been localized to the long arm (q) of chromosome 3 (3q26) (9) and covers 210 kb of genomic DNA that is defined by 31 exons (10,11). The mammalian PLD2 gene is found on the short arm (p) of chromosome 17 (17p13) (12), is defined by 25 known exons of a genomic region spanning 16.3 kb and encodes for two splice variants (PLD2a and PLD2b) of 933 amino-acids in length each (13), which yields functionally indistinguishable proteins of 106 kDa MW (14).

All members of the PLD superfamily possess two highly conserved phosphatidyltransferase HKD catalytic domains (HKD1 and HKD2) that are defined by the consensus peptide sequence HxK(x)4D(x)6GSxN, which are vital to the lipase activity. PLD1 and PLD2 also bear the phox homology (PX) and pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, both at the N-terminal end and the phosphatidylinositol 4,5- bisphosphate [PIP2] binding site (15). Two HKD motifs are requisite for catalytic activity (16). In case of salmonella endonuclease (nuc) the protein forms dimer to catalyze the reaction. In higher organisms the protein contains two HKD motifs suggesting a duplication and common origin. In these proteins, both the motifs tightly interact to form an active center (16,17). The HKD motifs are also present in other biologically diverse proteins such as bacterial phospholipid synthases, endonucleases, a pox envelope protein and a Yersinia toxin.

PLD1 and PLD2 are classical mammalian PLD isoforms (15). The PX and PH domains of PLD1 and PLD2 function as strong modulators of the membrane recycling machinery. It regulates, for example, interaction with SH2/SH3-containing tyrosine kinases (18,19). PLD3, PLD4, PLD5 and PLD6 isoforms lack PX and PH domains (20) and, therefore, could be considered non-classical PLDs.

Apart from lipase activity, PLD2 possesses guanine nucleotide exchange activity (GEF) for the small GTPase Rac2 and Ras (21–23). The PX domain of PLD2 contains the site for GEF activity, whereas both the PLD2-PX and -PH domains are involved in interacting with the small GTPase substrate (24), which can be either Rac2 or Ras (22,25).

In spite of these accomplishments characterizing PLD, there are not yet any resolved structures of the protein either from a crystallized protein or from NMR. Therefore, we set out to model the isoform of PLD2, using computational methods and selecting from among the candidate structures on the basis of their consistency with the experimental results.

We report here a 3D model of PLD2, fully based on biochemical data, which will help explain the 2 intermolecular enzymatic activities, as well as to reasonably predict the physiological behavior of PLD in cells, protein-protein interactions and phospholipid binding sites.

Having a working modeled structure of PLD will tremendously help in the rational design of more specific inhibitors that are proving to become quite important for recovering tumorigenesis (26), as relates to the PLD/phospholipid fields.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was from Mediatech (Manassas, VA); Opti-MEM, Lipofectamine, Plus reagent, and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); [3H]butanol was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO); [35S] GTPγS was from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA); ECL reagent was from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). The plasmids used in this experiment were as follows: pcDNA3.1-mycPLD2-WT, pcDNA3.1-mycPLD2-K758R, pcDNA3.1-mycPLD2-F129Y, pcDNA3.1-mycPLD2-R172C, pcDNA3.1-mycPLD2-D263-266, pRK5-myc-Rac2 or pCMV6-mycHRas, mCit-C1(pEYFP-C1)-YFP-PLD2 and pCerulean-C1-PLD2.

Cells and cell culture

COS-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Transfections

Transfections were performed using appropriate amounts of plasmid DNA, 5 μl Lipofectamine (Invitrogen), and 5 μl Plus reagent (Invitrogen) in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen), per the manufacturer’s protocol. COS-7 cells or RAW264.7/LR5 macrophages were transfected for 3 h, washed, re-fed with prewarmed complete medium, and maintained for 48 h. After 48 h, cells were harvested for their respective experiment. When necessary, post-transfection before harvesting, cells were treated with 10 nM EGF or IL-8 depending upon the experiment and the cell line for indicated time lengths.

Purification of PLD2 and Rac2 using baculoviral expression system

To generate a purified, recombinant, and full-length PLD2 or Rac2, a baculovirus expression system was used for the overexpression and subsequent purification. Briefly, the PLD2-WT or Rac2-WT genes and the Bsu36I-digested BacPAK5 viral DNA were co-transfected into Sf21 insect cells in separate reactions, which rescued the very large viral DNA and effectively transferred the PLD2 or the Rac2 genes separately into the AcMNPV genome. PLD2 or Rac2 baculoviral stocks were selected that overexpressed PLD2-WT or Rac2, respectively, and were used to infect Sf21 insect cells for further overexpression of PLD2 or Rac2 and subsequent purifications of PLD2 or Rac2 using the TALON matrix, as previously described in (27).

Immunoprecipitation, SDS-PAGE and western blot analyses

After transfection, cells were harvested and lysed with special lysis buffer (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 100 μM sodium orthovanadate, and 0.1% Triton X-100). The lysates were sonicated and the presence of overexpressed protein was confirmed by performing SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. For immunoprecipitation, the cell lysates were treated with 1 μl monoclonal antibody for the respective protein and 10 μl agarose beads (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and incubated at 4°C for 4 h. After incubation, the immunoprecipitates were washed with LiCl wash buffer (2.1% LiCl, 1.6% Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) and NaCl wash buffer (0.6% NaCl, 0.16% Tris-HCl, 0.03% EDTA, pH 7.4), respectively, and sedimented at 12,000 × g for 1 min. The resulting pellets were then analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blot (WB) analyses.

Lipase assay

Phospholipase D activity (transphosphatidylation) in cell sonicates was measured using short chain PC, 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC8) micelles or 1,2-diarachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3 phosphocholine (AraPC) or 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) liposomes and [3H] butanol. In case of long chain fatty acid containing PC, the liposomes were sonicated to form SUVs. Approximately 50 μl of cell sonicates were added to microcentrifuge Eppendorf tubes containing the following assay mix (120 μl final volume): 3.5 mM PC8 or DOPC or AraPC, 1 mM PIP2, 75 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, and 2.3 μCi (4 mM) of [3H]butanol. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 30 °C, and the reaction was stopped by adding 300 μl of ice-cold chloroform/methanol (1:2). Lipids were extracted and dried for thin layer chromatography (TLC). TLC lanes that migrated as authentic phospho butanol were scraped, dissolved in 3 ml of Scintiverse II scintillation mixture, and counted. Background counts (boiled samples) were subtracted from experimental samples.

GEF Activity: GTP binding

GTP ([35S]-GTPgS) binding of Rac2 or Ras was measured in the presence of immunoprecipitated PLD2-WT or PLD2-F129Y or PLD2-R172C. Recombinant PLD2-WT was used as the positive. Nineteen pmol of Rac2 was incubated with 8 μM GDP, 6 mM MgCl2 (20 μl volume) for 10 min at room temp. GDP-bound Rac2 was added to 20 μl 100 mM AMP-PNP, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 μM [35S]-GTPgS in the absence or presence of recombinant PLD2 or immunoprecipitated PLD2-WT or F129Y or R172C (45 μl volume). The relative amount of GTPgS-bound to Rac2 was measured by scintillation spectrometry.

Coimmunoprecipitation analyses

After transfection, cells were harvested and lysed with Special lysis buffer (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 100 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 0.1% Triton X-100). The lysates were sonicated and treated with 1 mlmonoclonal antibody for the respective protein and 10 ml agarose beads (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and incubated at 4°C overnight. After incubation, the immunoprecipitates were washed with LiCl wash buffer (2.1% LiCl, 1.6% Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) and NaCl wash buffer (0.6% NaCl, 0.16% Tris-HCl, 0.03% EDTA, pH 7.4), respectively, and sedimented at 12,000 X g for 1 min. The resulting pellets were then analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blot (WB) analyses.

Prediction of full-length PLD2 structure: homology modeling

Based on the experimental data, a list of amino acid residues that is key for PLD2 activities as well as PLD2’s interactions with other proteins was generated. This is shown in Table 1, and is used to assure the quality of the predicted structures.

Table 1.

Criteria based on experimental evidence that need to be applied to any predicted structure for validation.

List of important amino acid residues in PLD2 and their functional role that are used in this paper as criteria for the PLD2 molecular modeling. These criteria are a summary of data from both our lab and from other investigators, as listed in the references of the table. They present the starting experimental evidence used to test the model that, for example, certain amino acids that interact with other signaling proteins with known motifs (such as SH2 or SH3) need to be on the surface of PLD2 in order to bind to said proteins; or that certain alcohol-amino acids (Ser, Thr, Tyr) need to be also exposed to the surface in order to be phosphorylated; or that the histidines on the two catalytic motifs should be in close spatial proximity.

| Domain | Amino acids | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key sites of PLD2 PX domain | Phe(F) 107,129 Leu (L) 166, 173 Arg (R) 172 |

GEF catalytic site | 23, 24 |

| Lys (K) 101, 102 and 103 | Putative PKCz binding sites | 26 | |

| Ser(S) 134 | Putative Cdk5 phosphorylation site | 35 | |

| Pro (P) 145 and 148 | Putative PLCg binding sites | 36 | |

| Tyr(Y) 169 and 179 | Grb2 binding sites | 45 | |

| Thr (T) 175 | Putative Akt phosphorylation site | 46 | |

| Key sites of PLD2 PH domain | Ile (I) 255 - Val (V) 280 (CRIB 1) Ile (I) 306 - His (H) 323 (CRIB2) |

Putative Rac2 binding sites | 38 |

| Tyr (Y) 296 | Putative EGF-R phosphorylation site | 39 | |

| Other important sites of PLD2 | His (H)442-Gly(G) 457 (HEKLLVVDQVVAFLGG) His (H) 756 -Asn (N) 773 (HSKVLIADDRTVIIGSAN) |

HKD motif 1 HKD motif 2 |

10–16 20, 40 |

| Tyr (Y) 415 | Putative JAK3 phosphorylation site | 39 | |

| Tyr (Y) 511 | Putative Src phosphorylation site | 39 | |

| Thr (T) 566 | Putative PKC delta phosphorylation site | 44 |

Abbreviations:

GEF Guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity, PLC - Phospholipase C, Cdk5 - Cyclin D kinase 5, PKC - Protein kinase C, Grb2 - Growth factor receptor binding protein.

I-TASSER

Human PLD2’s amino acid sequence was obtained from NCBI, and submitted, to the protein structure prediction server, Iterative threading assembly refinement server (I-TASSER). I-TASSER threads the protein sequence through the PDB structure library and searches for the possible alignments. For unaligned regions, I-TASSER uses ab intio modeling. I-TASSER simulations can be run not only for the full chain, but also for the separate domains (28). Since I-TASSER-predicted full-length PLD2 is principally comprised of random secondary structures (not shown), we also obtained structures of domains separately. More than one solution was obtained for individual domain predictions. One out of the many solutions was chosen based on the criteria mentioned in Table 1. These were docked pair-wise to obtain a group of candidate structures of the complete protein. From this group, one final model was chosen visually, based on the criteria mentioned in Table 1.

Phyre-2

We also used the server, Phyre 2 (protein homology/analogy recognition engine), which is an improved version of Phyre. After creating the profile of non-redundant sequence, the secondary structure was predicted. Using the profile and model of secondary structure a full-length 3D models were generated. The missing parts that arise during the queues are determined by the loop library method (26). Finally, molecular modeling and visualization was performed using the Swiss PDB viewer (SPDBV). More than one solution was observed before finalizing the final structure. By visual inspection we concluded the PLD2 model predicted by Phyre2 server meets most of the criteria listed in Table 1. However, this model was not entirely energetically favorable as certain amino acid conformations are not viable. These issues were fixed by manually perturbing the structure using SPDBV and minimizing the result using steepest decent and conjugate gradient methods. Finally, the complete 3D model was energy minimized which resulted in a modeled structure, which was energetically favorable and consistent with experimental criteria listed in Table 1.

Molecular docking

The computer-simulated docking studies were performed using both HEX 6.1 and AutoDock Vina. In order to model the full-length 3D PLD2 structure from the different domains of PLD2 (obtained from I-TASSER) as well as for docking two (PLD2/Rac2) the HEX (29) was used. The structure of Rac2 was obtained from PDB database (PDB IDs 2W2T). HEX is a macromolecular docking program that takes into consideration both shape and electrostatic charge. In predicting molecular docking juxtapositions, it uses spherical polar fourier (SPF) correlations to accelerate the docking calculations. In many respects, this approach is similar to conventional fast Fourier transform (FFT) docking methods, which use Cartesian grid representations of the molecular shape and electrostatic properties and translational FFTs to perform docking correlations. The default docking control parameters of the HEX program were used to arrive at 100 docked conformations (30). In all the HEX dockings, PLD2 was treated as receptor while the other protein partner was treated as ligand.

Enzyme-substrate docking

For docking PLD2 with its substrate 1, 2 di-octanoyl phosphatidyl choline (PC8), PC8 structure was retrieved from the PDB database, ID: 2LYA. PLD2 and the substrate 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC8) were submitted to Autodock Vina (31). Autodock Vina allows the ligand to have flexible/rotatable bonds. Docking with AutoDock Vina starts by defining a search space or binding site in a restricted region of the protein. The coordinates of Lys 444 zeta nitrogen lie between the two catalytic Histidines (442 and 756) in our 3D model. Therefore, in the present study, the receptor grid was generated using the coordinates of Lysine 444. The resulting docking conformation was further visualized using the PyMOL.

Using the same conditions, docking experiments were performed with phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE) and di-oleoyl phosphatidyl serine (PS), in order to explain the ability and specificity of PLD2 towards PC. Structures of PE and PS were retrieved from the PDB IDs 3B74 (32) and 2LYB (33) respectively. To determine PIP2 binding sites on PLD2, docking experiments were performed with PLD2 and phosphatidyl inositol 4, 5- bisphosphate (PIP2) whose structure was retrieved from the PDB ID, 3W68 (34).

Coordinates

Access to the full-length modeled structure created in this paper can be found in the Supplementary data file “PLD2 coordinates of 3D structure model” with PDB that contains PDB coordinates in text format. These coordinates can be used by any investigator to reconstruct the three-dimensional model we are presenting in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean + SEM. The difference between means was assessed by the Single Factor Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test. Probability of p<0.05 indicated a significant difference.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A 3D modeled structure of PLD2

The absence of a crystal structure for mammalian PLD2 hinders advances in the field of PLD biology. To remedy this situation, we combined modeling tools with biochemical evidence, such as substrate accessible active site(s) and solvent accessible phosphorylation sites to obtain a structural model. A compilation of criteria including considerable experimental evidence is shown in Table 1 (10,21,24,35–47). These criteria are a summary of data from both our lab and from other investigators, as listed in the references of the table. They present the starting experimental evidence used to test the model that, for example, certain amino acids that interact with other signaling proteins with known motifs (such as SH2 or SH3) need to be on the surface of PLD2 in order to bind to said proteins; or that certain alcohol-amino acids (Ser, Thr, Tyr) need to be also exposed to the surface in order to be phosphorylated; or that the histidines on the two catalytic motifs should be in close spatial proximity. Since the large majority of the criteria were fulfilled with the initial model, we used it to further refine a predicted PLD2 structure.

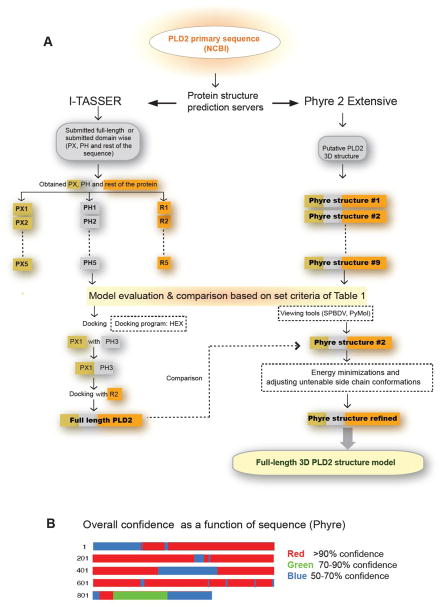

The strategy we followed to obtain the full-length 3D model of PLD2 is pictorially shown in Figure 1A, which used two different protein prediction programs algorythms, implemented by either I-TASSER or Phyre and compared the resulting structures (28,48). In either case, the scoring that the structure solving programs provide had to be orthogonal with the biological and biochemical data on Table 1. For example, energy minimization was run only after a candidate structure has checked out all requisites of Table 1.

Figure 1. Phospholipase D2 is dual enzyme that bears guanine nucleotide exchange as well as lipase activity.

(A) Self-explanatory schematic representing the strategy applied in this study to obtain a PLD2 three- dimensional structure. Briefly, PLD2 primary sequence was submitted to I-TASSER and Phyre 2 Extensive protein prediction servers. Both the servers provided with more than one solution, which were evaluated based on set criteria (the laboratory bench marks) listed in Table 1. (B) Summary of confidence in the structural model of PLD2. Confidence in the PLD2 structure, as estimated by Phyre2, is displayed as a function of position in the proteins’s primary structure.

PLD2 structure prediction - Phyre versus I-TASSER

When a full sequence was submitted to I-TASSER, the HKD motifs were comparable to the crystallized bacterial HKD members. However, a major part of the resulting structure was found to be random without the expected PX and PH domains. To remedy this, domain-wise structures were obtained from I-TASSER (28). More than one solution was obtained for each domain. Individual domains were chosen based on the set criteria in Table 1. Next, using the program HEX, we docked the globular domains of the possible solutions. The lowest energy docking orientation was selected and the primary structures of the fragments were linked to obtain the full-length modeled structure (predicted at pH 7). In a complementary approach, the full-length PLD2 sequence was submitted to the Phyre2 server for “Intensive’’ modeling (48). Multiple solutions were obtained out of which, the 3D model structure that satisfied the set criteria in Table 1 and that with the lowest energy score was selected. The confidence of the resulting model estimated by Phyre2 is summarized in Figure 1B, which represents the overall confidence as a function of sequence. It is worth mentioning that in the Phyre-predicted structure, 71% of the residues of PLD2 were modeled at greater than 90% confidence. Analysis of I-TASSER- and Phyre-predicted PLD2 structures revealed that the criteria listed in Table 1 are convincingly demonstrated to a larger extent in Phyre-PLD2 and therefore we pursued the Phyre predicted model for PLD2 3D structure.

Refining Phyre PLD2

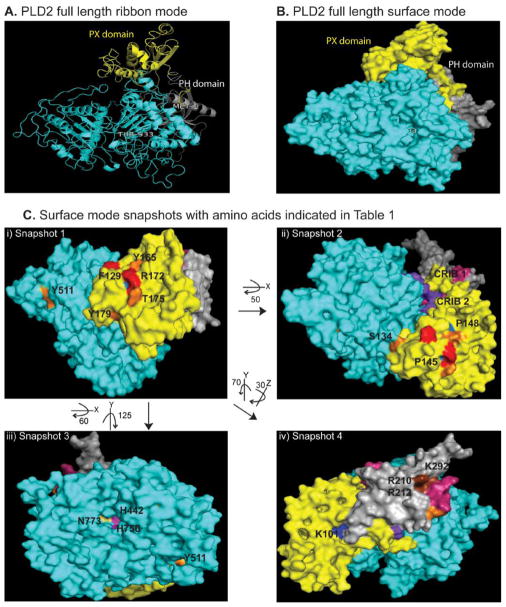

The initial structural model obtained (that fulfilled criteria in Table 1) was not energetically minimized. In several instances, sidechains were in untenable conformations such as steric hindrances between some of the amino acid sidechains. Therefore, the model was globally adjusted manually and through a combination of steepest decent (1000 step) and conjugate gradient (300 step) energy minimizations implemented by SPDBV (49). Bulk dielectric constants were used for these calculations instead of explicit solvent molecules. All these steps provided gave us a biochemically agreeable, energetically favorable, full-length PLD2 3D model. This model is shown in Figure 2, where active sites, protein binding sites and phosphorylation sites are labeled in different colors (Figure 2). Access to the full-length modeled structure created in this paper can be found in the Supplementary data file “PLD2 coordinates of 3D structure model” with PDB that contains PDB coordinates in text format.

Figure 2. PLD2 full-length structure model in three dimensions.

(A,B) PLD2 3D structure in ribbon (A) and surface (B) modes. PX and PH domains of the protein are shown in yellow and gray, respectively, while the rest of the protein is shown in blue. (Ci-Civ) Different snapshots (snapshot 2 is turned 50° X, snapshot 3 is turned 60° X, 125° Y, snapshot 4 is turned 70° anticlockwise Y, 30° Z from snapshot 1 as indicated in the Figure) of PLD2 3D structure model in surface mode indicating that the important amino acids that interact with the binding partners or subject to post translational modifications are exposed to the solvent. Color code is as follows: Yellow - PX domain, Silver- PH domain, Cyan - Rest of the PLD2 bearing HKD motifs, Magenta - Lipase sites, Red- GEF sites, Orange - putative Phosphorylated sites, Brown - Putative lipid binding sites, Dark blue PKC binding sites, Skyblue - PLC binding sites, Pink - CRIB1, Purple - CRIB2. Full access of this model can be found along with the paper in the website “PLD2 3D structure model” with PDB coordinates in text format.

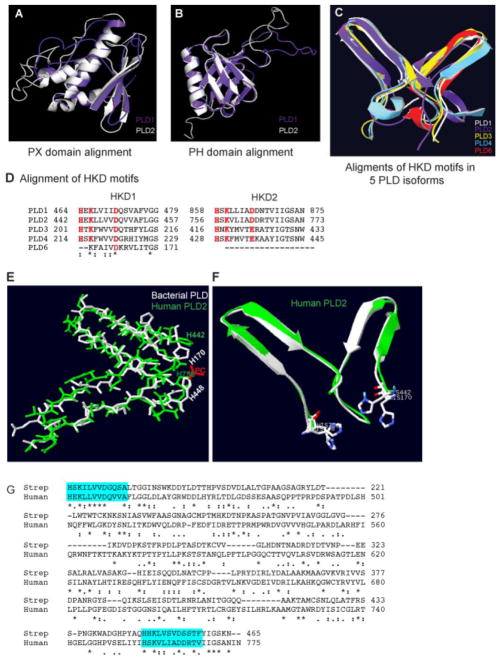

A 3D comparison of PLD isoforms

Next, we sought to compare sequence as well as the modeled structure of PLD2 with other mammalian isoforms. First, we obtained the predicted structures of PLD1 and PLD3-6 via Phyre2 server (energy minimizations were not performed for these structures). A multiple sequence alignment of PLD1 through 6 was performed using Clustal W, following which we compared predicted 3D structures of PLD1, 3, 4 and 6 isoforms with our PLD2 structural model. It is known that PLD1 and 2 are the only mammalian isoforms that contain the regulatory PX and PH domains. Figures 3A and B shows the structural alignment of the PX and PH domains of PLD1 and 2, respectively. The two HKD motifs are spatially or three-dimensionally conserved among the PLD1 through 6 isoforms (Figure 3C). Sequence alignments of the HKD motifs of PLD isoforms is shown in Figure 3D. Amongst the mammalian PLD isoforms, only PLD1, 2 and 6 possess lipase activity. The lack of lipase activity in PLD3 and 4 cannot be attributed to the absence of PX and PH domains, since PLD6 also lacks these domains and is still active upon dimerization.

Figure 3. Structural and sequence alignment of known mammalian PLD isoforms.

Based on the model of Figure 3 here are depicted three dimension structure alignment of PLD1 (white) and PLD2 (purple) PX (A) and PH (B) domains. (C) Catalytic HKD motifs of PLD1-PLD6 show perfect alignment three dimensionally. (D) Sequence alignment of HKD motifs of the known mammalian PLD isoforms (PLD1, 2, 3, 4 and 6). (E, F) Superimposed active sites of streptomyces PLD (white) along with the substrate dibutyryl phosphatidylcholine (Red) (PDB ID: 1VOV) and human PLD2 structure model (green). (G) Sequence alignment of streptomyces PLD (170 -465) and human PLD2 (446 -775) with HKD motifs highlighted in cyan boxes.

Next, we wanted to compare the catalytic site of our PLD2 structure model, with that of streptomyces PLD that was crystallized along with its substrate dibutyrylphosphatidyl choline (PDB ID: 1VOV) (50). Figure 3E and F shows the superimposed streptomyces (white) and human PLD (green) active site residues, while Figure 3G shows sequence alignment of the same. These results indicate that the active site residues of our predicted model for the PLD2 structure fits with the existing bacterial PLD crystal structure to a larger extent. Specifically the orientation of the two key amino acids, Histidines 442 and 756, those that play an important role in the phosphatidyl choline hydrolysis are aligned.

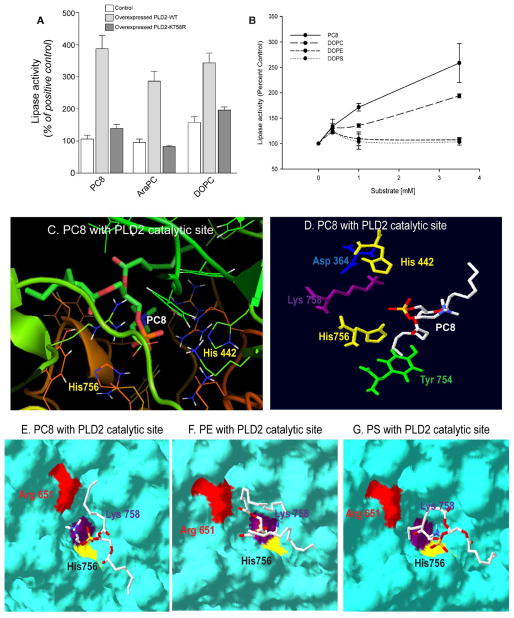

Modeling of PLD2 complexed with phosphatidyl choline

Once we found that the active site residues superimpose, we decided to test it by performing theoretical docking studies with its substrate phosphatidylcholine (PC) and with known protein interacting partners. Examining these binding/interactions with the PLD2 model of Figure 3 allowed for us to test our model in silico. Based on biochemical experimental data, the two histidines in the HKD motifs play an important role in the catalytic conversion of PC to PA and choline (15,50,51). We first performed lipase assays using variety of phosphatidylcholine species (Figure 4A) as well as other phospholipids (Figure 4B). Results shown in Figure 4A indicate that PLD2-WT, but not PLD2-K758R can breakdown a variety of PC species, including 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC8), 1,2-diarachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (AraPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC). Figure 4B indicates that C8-PC followed by DOPC, but neither PE nor PS serves as substrates for this PLD2.

Figure 4. PLD2 lipase catalytic site forms a groove that fits the substrate PC.

(A) Lipase assay of cells that were untransfected (white bars) or transfected with PLD2-WT (gray bars) or lipase inactive mutant, PLD2-K758R (black bars) against 3 different phosphatidylcholines: 1,2-di-octanoyl (PC8), 1,2-di-arachidonoyl (Ar PC) or 1,2 dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC). (B) Lipase activity performed with increasing concentrations of different phospholipids, PC8, DOPC, Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and Phosphatidylserine (PS) ranging from 0 to 3.5 mM. (C-D) Using the model depicted in Figure 2, shown here is the lipase catalytic site groove of PLD2 with the substrate PC8 (C). (D) Orientation of key aminoacids in the active site of PLD2 towards the substrate PC8. (E, F) PLD2 HKD catalytic site with the PC8 (E) PE (F) and PS (G) in surface mode that shows orientation of PC8 is in such a way that facilitates choline release from the HKD groove while the same is not true in case of PE or PS.

Next, to demonstrate phospholipid accommodation in PLD2’s presumptive active site pocket of the 3D structural model of PLD2, initial docking was performed with PLD2 and PC8 (from PDB ID: 2LYA) (33) by employing autodock vena (31). PLD2 was treated as receptor, whereas PC8 as a small molecule ligand. The search space was centered at the location of lysine 444 that lies between the two Histidine residues. Of the solutions derived by autodock, the best scoring conformation was presented in Figure 4C and D, which shows PLD2’s active site (Figure 4C) with the substrate PC8. The orientation of the key amino acids in the active site is more clearly shown in Figure 4D.

Modeling of PLD2 with other phospholipids

Figure 4B suggests that PLD2 while hydrolyzes PC, it is not able to hydrolyze other phospholipids, PE and PS. Therefore, we next wanted to determine the specificity of PLD2’s putative lipase active site pocket in silico. Using the same conditions that we used to dock PC8, we performed docking with the phospholipids phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (PDB ID: 3B74) (32) and phosphatidylserine (PS) (PDB ID: 2LYB) (33). Panels in Figures 4E, F and G show PLD2’s presumtive active site docked with PC8, PE and PS. A closer observation of these results led us speculate that the choline group on PC is oriented outwards making the choline release easy. In case of both PE and PS, the head groups are oriented inward into the presumptive active site pocket. We propose that this makes the release of head group difficult when compared to that of PC, further affecting the hydrolysis. All this explains the PLD2’s ability to hydrolyze PC but not PE and PS (Figure 4B). However whether PS or PE can act as inhibitors of PLD2 is not clear, as these experiments were performed with one substrate at a time (PS or PC or PE). In reality, other factors such as, affinity of the enzyme (PLD2) to the substrate and the amount of the substrate available and accessible to the enzyme determine the formation of enzyme substrate complex resulting in the product. Also additional in silico experiments with PLD2 3D structure model with other possible phospholipid substrates such as lysoPC, will give insight on PLD2’s catalysis.

Mechanism of PLD2 lipase reaction, based on structural details

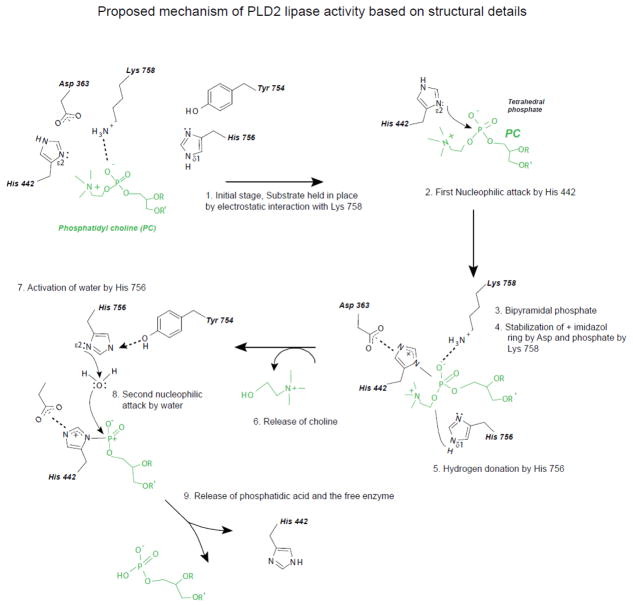

Based on our model of PLD2 3D structure and its docking with the substrate PC8 (Figure 4C-D), we propose the working model for human PLD2 lipase activity (Figure 5). The reaction could take place in three steps that are explained as follows:

Figure 5. Mechanism of PLD2 lipase activity.

Based on the structural details obtained from Figure 4, we propose the following steps in PC hydrolysis by PLD2. (A) Histidine 442 exerts a nucleophilic attack on phosphate moiety of PC, with the help of Aspartate 363. (B) His 756, Lysines 444 and 758 might be involved in stabilizing the tetrahedral intermediate. (C) In the final step, Histidine 756 donates hydrogen to the tetrahedral intermediate and activates water, which then exerts a second nucleophilic attack, ultimately leading to the release of choline and phosphatidic acid (PA) respectively.

With the help of the Aspartic acid 363, Histidine 442 (Ne) nucleophilically attacks the phosphate group on the substrate phosphatidyl choline. This will form the tetrahedral phosphatidyl enzyme intermediate as explained in (50,52).

The tetrahedral intermediate thus formed needs to be stabilized. Histidine 756, Lysines in the HKD motif, Lysine 444 and 758 might play a crucial role in doing so. Lysines might have a role in stabilizing the negative charges of the oxygens on the phosphate. Mutation of lysine 758 completely inactivates the lipase.

Histidine 756, on the other hand will participate in the reaction possibly by donating a proton (Nd) leading to the release of choline. Subsequently, with the help of Tyrosine 754, Histidine 756 activates water. A second nucleophilic attack will takes place where water will nucleophilically attack the phosphate moiety. This will result in the formation of phosphatidic acid (PA).

Also the superimposition of bacterial PLD and human PLD2 (Figure 3E) indicates the conserved orientation of the key aminoacids as well as the secondary structures. All this is in agreement with the mechanism of lipase action of bacterial PLD that was based on crystal structure (50,51). These facts suggest that the presented model for PLD2 3D structure is comparable to the bacterial PLD in terms of lipase reaction mechanism. In addition, we are able to explain other existing biochemical findings with the proposed 3D structure model.

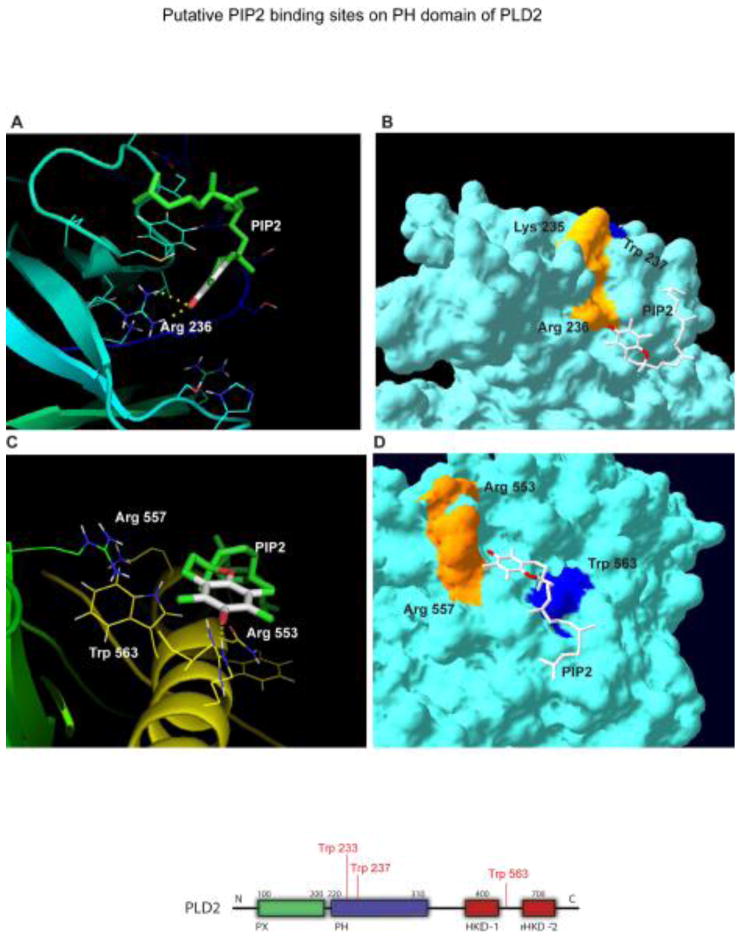

Modeling of PLD2 structure model with PIP2

It is well established that phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is one of the positive regulators of PLD2 (53). Therefore we sought to determine the possible putative binding site for PIP2 on PLD2. Biochemical data from the literature suggest that PIP2 might have two binding sites on PLD2, one at PH domain and the other towards the C-terminus (54). In the same study they showed that Arginine 237 and Tryptophan 238 are essential for PIP2 mediated localization of PLD2. In the same study they also suggested the possible PIP2 binding regions binding in the C-terminal region (54). PIP2 binding regions in various proteins are not well defined, but generally is comprised of clusters of basic and aromatic aminoacid residues. In a study by Sciorra et al (55), it was speculated that the region between 554–575 aminoacids in mouse PLD2 might be a putative PIP2 binding region. This region corresponds to 531–564 in human PLD2 (hPLD2). By mutational analysis they showed that Arginines 554 (R553 in hPLD2) and 558 (R557 in hPLD2) contribute in responding to PIP2 (55). However many other possible basic amino acids in that region, which might play a role in binding to PIP2 binding cannot be ruled out. In order to determine if our model can predict the new binding sites or if it can dock PIP2 to the proposed binding sites, we performed docking experiments.

Docking was performed with PIP2 (PDB ID: 3W68) and our PLD2 structure model with the search site focused at PH domain and between 532 and 564 aminoacids. Out of the solutions obtained, we chose three solutions (Figure 6). In each of these, polar inositol ring is oriented towards the basic aminoacid residue and the hydrophobic tail is oriented towards aromatic aminoacids, mostly tryptophan. The first two solutions are R236 and W238 (Figure 6A), R557 and W563 (Figure 6B) that were suggested to be involved in PIP2 interaction. This information is in consistent with our model for PLD2 3D structure. Figure 6C on the other hand, shows a novel putative PIP2 binding region in PH domain, which involves R210, R212 and W233. Nevertheless, this requires experimental confirmation.

Figure 6. Prediction of PIP2 binding sites in the PH domain of PLD2.

(A–F) Using the model depicted in Figure 2, shown here is the docking between PLD2 and PIP2 (PDB ID: 3W68) in ribbon (A, C and D) or surface (B, D and F) modes. Effect of PLD2 putative PIP2 binding site double mutant R210/212A on lipase activity in the presence of PIP2 determined by performing a lipase activity assay. Cell lysates (G) or intact cells (H) were treated with increasing concentrations of PIP2 (0 to 10 mM) and lipase assay was performed. PIP2 binding mutant is irresponsive in the presence of PIP2 unlike PLD2-WT.

These results indicate that the polar region of PIP2 might interact with the basic aminoacid residues that are clustered and are surface exposed. R210, 212, and 236 as well as K235 are all present as a cluster in the near vicinity. The possibility of more than one PIP2 molecule interacting with multiple basic aminoacid clusters at the same time is quite possible. In Figures 6A, B and C, the docking conformation of PLD2 and PIP2 were shown in ribbon and surface modes. Along with the basic aminoacids, aromatic aminoacids such as W might also play a role by interacting with hydrophobic regions of PIP2.

Next, we wanted to explore the effect of the novel putative PIP2 binding mutants (R210 and R212 on lipase activity in the presence of PIP2. In order to do that a PLD2 double mutant was made where R210 and R212 were mutated to Alanine. Intact cells or cell lysates overexpressing either PLD2-WT or PLD2-R210/212A, were treated with increasing concentrations of PIP2 ranging from 0 to 10 mM and lipase activity was determined. The results presented in Figure 6G and H suggests that PIP2 exerted a positive effect on PLD-WT expressing cells in a dose-dependent fashion, as expected. Interestingly mutating the putative PIP2 sites (R210 and R212), made PLD2 irresponsive to PIP2.

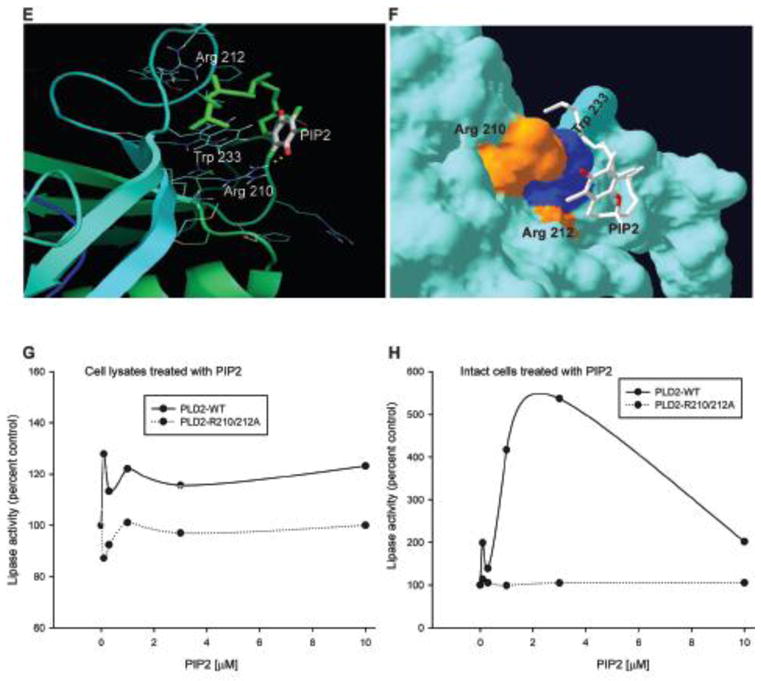

Protein interactions of PLD2: PLD2 and Rac2 molecular modeling

We next wanted to determine if our model could explain the protein-protein interactions of PLD2. From previous studies in our lab, we know that PLD2 and Rac2 interact with each other and in addition, Rac2 influences PLD2 activity (38,56). While this suggests that PLD2 is an effector of Rac2, PLD2 acts as GEF for Rac2 and acts upstream (24). Representative data showing the same is presented in Figure 7A–B. Figure 7C shows our modeled PX domain (from Figure 2) has PLD2-GEF catalytic residues highlighted. From the three-dimensional model, it is obvious that residues F107, F129, L166, and L173 might form a hydrophobic pocket, which we speculate might be involved in promoting nucleotide exchange on Rac2.

Figure 7. PLD2 and Rac2 transmodulate each other.

(A) GEF activity of PLD2-WT when compared to the GEF deficient PLD2-F129Y or PLD2-R172C. (B) Lipase activity of PLD2-WT is significantly reduced in the presence of Rac2, suggesting a negative effect of Rac2 on PLD2. Activity of PLD2D263-266, which is deficient in binding to Rac2, is rescued. (C) Modeled PLD2-PX domain (ribbon) showing GEF site, and the key amino acid residues involved are listed. (D and E) Docking model of PLD2 and Rac2 in ribbon (D) and surface (E) modes showing binding of two Rac2 molecules, one upstream (blue) (that has a negative effect on PLD2) and one downstream (magenta) (that is activated by PLD2-GEF activity). Color code: PX and PH domains of PLD2 are in yellow and gray colors, respectively. Shown in aqua blue and and magenta are upstream and downstream Rac2 molecules, respectively. In both Rac2 molecules, red and blue colors represent switch I and II, respectively. Labels are represented in same colors as that of each domain.

The fact that Rac2 is both upstream affecting PLD2 and downstream activated by PLD2 suggests the possibility of more than two binding sites for Rac2 on PLD2. Taking into consideration these sets of facts, we wanted to see if our PLD2 3D modeled structure was in agreement with these experimental findings. We used the PLD2 modeled structure and performed HEX docking (57) with a first Rac2 molecule (PDB id: 2W2T) (58). From the several docking results that were generated, an energetically favorable complex was chosen and docked with another molecule of Rac2 (Figure 7D, E). In agreement with the experimental data, two Rac2 molecules are in close proximity to the PLD2-PX and -PH domains.

We believe that the upstream Rac2 (shown in navy blue) that regulates PLD2 via binding is in closer proximity to the CRIB motifs (gray and purple) of the PLD2-PH domain (Figure 7D, E). On the other hand, the PLD2-GEF catalytic site (green) is in close proximity to the downstream Rac2 (magenta) switch I (red) (Figure 7D, E), which in conventional GEF catalysis is usually perturbed by upstream GEFs. All this correlates with the results of mutational analysis, which identified residues in the PLD2-PX as GEF residues. Overall, PLD2-GEF activates Rac2, while at the same time PLD2 is an effector protein for active Rac2-GTP.

Why is our model for PLD2 3D structure significant?

Modeling experiments were performed using the ITASSER server (28) and the Phyre 2 (48) server. In both cases multiple models are predicted and a “best” model is suggested. Groups that created each of these servers used them in the recent Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction experiment (CASP 10). This experiment assesses the ability of protein prediction algorithms and servers to predict protein structures for proteins prior to their determination by x-ray crystallography. From about 70 protein prediction servers created by structural biomedical/bio computational scientists across the protein structure prediction community, I-TASSER performed best and Phyre 2 was in the upper 30% for prediction of three dimensional protein structure from primary sequences. An interesting finding in this experiment was that these servers found the correct conformation much more frequently among the top scoring 10 or so candidate models, but were unable to correctly choose which of these was best.

This argues first, that the prediction methods used in this paper were among the very best at the current state of the art and second, that the chances of selecting the best structural model are greatly improved by supplementing largely energy-based scoring methods with alternative information about a protein’s structure. This information includes biological activity and information, for example molecule binding properties. Here we use just such biological information in conjuction with sound structure prediction methodologies to identify models that are consistent with known Phospholipase biology and are heuristic, suggesting both features of these enzymes and how these features can be tested.

CONCLUSIONS

We present here a 3D modeled structure of PLD2 fully based on biochemical and biological data and, in turn, explain several models of how this enzyme interact with other cell signaling proteins. Since a 3D structure for mammalian PLD has not previously been determined (crystallography, NMR or otherwise) or predicted by any laboratory, this contribution is first as far as we can understand.

The model provides a structural basis that explains previously published biological and biochemical findings by our and other labs. The predicted modeled structure explains the active site, several motif homologies with other mammalian PLD isoforms and interaction with known small molecule inhibitors. This is important since PLD2 has been recently described as a tumorigenic and metastasis inducing protein. Finding good docking inhibitors will be important for understanding and modulating pathology. The model also predicts what other proteins should bind to PLD (we are giving the example of Rac2). Further, it can be used to study the other enzymatic activity in PLD that is, a GEF activity.

This study established a firm foundation for future bioinformatics-based studies using full-length PLD2 as a model. While PLD2 activity has been shown to be necessary for cellular processes, like leukocyte chemotaxis and phagocytosis, and general cell migration. Deregulated PLD2 levels were reported in several cancers such as breast, colorectal and renal (59–63). A recent publication from our own lab reported a study in which the presence of PLD2 promoted the formation of aggressive tumors in mice, while silencing PLD2 reduced tumor size (3). All this suggests an increasing demand for the availability of PLD2’s 3D structure, which can then be used to design specific and efficient small molecule inhibitors or modulators that will regulate PLD2 activities/protein interactions.

The predicted 3D model of PLD2’s structure reported here is in accordance with the experimental evidence to a very large extent. From the docking results with the known PLD2 binding partners presented in the current study, we believe that exceptional modulators of PLD2 can be developed more efficiently. The current model has also paved a way to determine how PLD2 associates with the membrane when stimulated and the regulatory structural dynamics. The model should also constitute the basis for the discovery of new enzymatic properties on PLDs and new protein-protein associations with signaling proteins or lipids.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The first structure model for mammalian PLD, in the absence of any resolved structure, crystallized or NMR.

A model based on biochemical data that predicts the active site accommodation of substrate, mechanism of reaction and interactions with other proteins during cell signaling

The model for the PLD2 structure is consistent with experimental observations and predicts new findings, such as the discovery of a phosphoinositide-binding site previously unknown.

As PLD2 is tumorigenic, the 3D structure is crucial for developing new inhibitors of in vivo activity.

Acknowledgments

The following grants to Dr. Cambronero (J.G-C.) have supported this work: HL056653-14 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 13GRNT17230097 from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data: Structure access to the full-length model created in this paper can be found along with the paper in the file “PLD2 coordinates of 3D structure model” with PDB coordinates in text format.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gomez-Cambronero J. Phosphatidic acid, phospholipase D and tumorigenesis. Advances in biological regulation. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez-Cambronero J. New concepts in phospholipase D signaling in inflammation and cancer. Scientific World Journal. 2010;10:1356–1369. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henkels KM, Boivin GP, Dudley ES, Berberich SJ, Gomez-Cambronero J. Phospholipase D (PLD) drives cell invasion, tumor growth and metastasis in a human breast cancer xenograph model. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Hongu T, Sato T, Zhang Y, Ali W, Cavallo JA, van der Velden A, Tian H, Di Paolo G, Nieswandt B, Kanaho Y, Frohman MA. Key roles for the lipid signaling enzyme phospholipase d1 in the tumor microenvironment during tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra79. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruchaga C, Karch CM, Jin SC, Benitez BA, Cai Y, Guerreiro R, Harari O, Norton J, Budde J, Bertelsen S, Jeng AT, Cooper B, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Levitch D, Hsu S, Choi J, Ryten M, Consortium UKBE, Hardy J, Ryten M, Trabzuni D, Weale ME, Ramasamy A, Smith C, Sassi C, Bras J, Gibbs JR, Hernandez DG, Lupton MK, Powell J, Forabosco P, Ridge PG, Corcoran CD, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Munger RG, Schmutz C, Leary M, Demirci FY, Bamne MN, Wang X, Lopez OL, Ganguli M, Medway C, Turton J, Lord J, Braae A, Barber I, Brown K, Passmore P, Craig D, Johnston J, McGuinness B, Todd S, Heun R, Kolsch H, Kehoe PG, Hooper NM, Vardy ER, Mann DM, Pickering-Brown S, Brown K, Kalsheker N, Lowe J, Morgan K, David Smith A, Wilcock G, Warden D, Holmes C, Pastor P, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Brkanac Z, Scott E, Topol E, Morgan K, Rogaeva E, Singleton AB, Hardy J, Kamboh MI, St George-Hyslop P, Cairns N, Morris JC, Kauwe JS, Goate AM The Alzheimer’s Research, UKC. Rare coding variants in the phospholipase D3 gene confer risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshikawa F, Banno Y, Otani Y, Yamaguchi Y, Nagakura-Takagi Y, Morita N, Sato Y, Saruta C, Nishibe H, Sadakata T, Shinoda Y, Hayashi K, Mishima Y, Baba H, Furuichi T. Phospholipase D family member 4, a transmembrane glycoprotein with no phospholipase D activity, expression in spleen and early postnatal microglia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anney R, Klei L, Pinto D, Regan R, Conroy J, Magalhaes TR, Correia C, Abrahams BS, Sykes N, Pagnamenta AT, Almeida J, Bacchelli E, Bailey AJ, Baird G, Battaglia A, Berney T, Bolshakova N, Bolte S, Bolton PF, Bourgeron T, Brennan S, Brian J, Carson AR, Casallo G, Casey J, Chu SH, Cochrane L, Corsello C, Crawford EL, Crossett A, Dawson G, de Jonge M, Delorme R, Drmic I, Duketis E, Duque F, Estes A, Farrar P, Fernandez BA, Folstein SE, Fombonne E, Freitag CM, Gilbert J, Gillberg C, Glessner JT, Goldberg J, Green J, Guter SJ, Hakonarson H, Heron EA, Hill M, Holt R, Howe JL, Hughes G, Hus V, Igliozzi R, Kim C, Klauck SM, Kolevzon A, Korvatska O, Kustanovich V, Lajonchere CM, Lamb JA, Laskawiec M, Leboyer M, Le Couteur A, Leventhal BL, Lionel AC, Liu XQ, Lord C, Lotspeich L, Lund SC, Maestrini E, Mahoney W, Mantoulan C, Marshall CR, McConachie H, McDougle CJ, McGrath J, McMahon WM, Melhem NM, Merikangas A, Migita O, Minshew NJ, Mirza GK, Munson J, Nelson SF, Noakes C, Noor A, Nygren G, Oliveira G, Papanikolaou K, Parr JR, Parrini B, Paton T, Pickles A, Piven J, Posey DJ, Poustka A, Poustka F, Prasad A, Ragoussis J, Renshaw K, Rickaby J, Roberts W, Roeder K, Roge B, Rutter ML, Bierut LJ, Rice JP, Salt J, Sansom K, Sato D, Segurado R, Senman L, Shah N, Sheffield VC, Soorya L, Sousa I, Stoppioni V, Strawbridge C, Tancredi R, Tansey K, Thiruvahindrapduram B, Thompson AP, Thomson S, Tryfon A, Tsiantis J, Van Engeland H, Vincent JB, Volkmar F, Wallace S, Wang K, Wang Z, Wassink TH, Wing K, Wittemeyer K, Wood S, Yaspan BL, Zurawiecki D, Zwaigenbaum L, Betancur C, Buxbaum JD, Cantor RM, Cook EH, Coon H, Cuccaro ML, Gallagher L, Geschwind DH, Gill M, Haines JL, Miller J, Monaco AP, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Paterson AD, Pericak-Vance MA, Schellenberg GD, Scherer SW, Sutcliffe JS, Szatmari P, Vicente AM, Vieland VJ, Wijsman EM, Devlin B, Ennis S, Hallmayer J. A genome-wide scan for common alleles affecting risk for autism. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:4072–4082. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ipsaro JJ, Haase AD, Knott SR, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. The structural biochemistry of Zucchini implicates it as a nuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012;491:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature11502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SH, Chun YH, Ryu SH, Suh PG, Kim H. Assignment of human PLD1 to human chromosome band 3q26 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;82:224. doi: 10.1159/000015105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond SM, Jenco JM, Nakashima S, Cadwallader K, Gu Q, Cook S, Nozawa Y, Prestwich GD, Frohman MA, Morris AJ. Characterization of two alternately spliced forms of phospholipase D1. Activation of the purified enzymes by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, ADP-ribosylation factor, and Rho family monomeric GTP-binding proteins and protein kinase C-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3860–868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katayama K, Kodaki T, Nagamachi Y, Yamashita S. Cloning, differential regulation and tissue distribution of alternatively spliced isoforms of ADP-ribosylation-factor-dependent phospholipase D from rat liver. Biochem J. 1998;329 (Pt 3):647–652. doi: 10.1042/bj3290647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SH, Ryu SH, Suh PG, Kim H. Assignment of human PLD2 to chromosome band 17p13.1 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;82:225. doi: 10.1159/000015106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steed PM, Clark KL, Boyar WC, Lasala DJ. Characterization of human PLD2 and the analysis of PLD isoform splice variants. Faseb J. 1998;12:1309–1317. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster DA, Xu L. Phospholipase D in cell proliferation and cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:789–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frohman MA, Sung TC, Morris AJ. Mammalian phospholipase D structure and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1439:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exton JH. Phospholipase D. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;905:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sung TC, Roper RL, Zhang Y, Rudge SA, Temel R, Hammond SM, Morris AJ, Moss B, Engebrecht J, Frohman MA. Mutagenesis of phospholipase D defines a superfamily including a trans-Golgi viral protein required for poxvirus pathogenicity. Embo J. 1997;16:4519–4530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang LQ, Seifert A, Wu DF, Wang X, Rankovic V, Schroeder H, Brandenburg LO, Hoellt V, Koch T. Role of phospholipase D2/phosphatidic acid signal transduction in {micro}- and {delta}-opioid receptor endocytosis. Mol Pharmacol. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.063107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen Y, Xu L, Foster DA. Role for phospholipase D in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:595–602. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.595-602.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selvy PE, Lavieri RR, Lindsley CW, Brown HA. Phospholipase D: enzymology, functionality, and chemical modulation. Chemical reviews. 2011;111:6064–6119. doi: 10.1021/cr200296t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahankali M, Peng HJ, Henkels KM, Dinauer MC, Gomez-Cambronero J. Phospholipase D2 (PLD2) is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the GTPase Rac2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19617–19622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114692108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henkels KM, Mahankali M, Gomez-Cambronero J. Increased cell growth due to a new lipase-GEF (Phospholipase D2) fastly acting on Ras. Cell Signal. 2013;25:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon H, Kwak D, Noh J, Lee MN, Lee CS, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Phospholipase D2 induces stress fiber formation through mediating nucleotide exchange for RhoA. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1320–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahankali M, Henkels KM, Alter G, Gomez-Cambronero J. Identification of the Catalytic Site of Phospholipase D2 (PLD2) Newly Described Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor Activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41417–41431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckert LB, Repasky GA, Ulku AS, McFall A, Zhou H, Sartor CI, Der CJ. Involvement of Ras activation in human breast cancer cell signaling, invasion, and anoikis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4585–4592. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott SA, Selvy PE, Buck JR, Cho HP, Criswell TL, Thomas AL, Armstrong MD, Arteaga CL, Lindsley CW, Brown HA. Design of isoform-selective phospholipase D inhibitors that modulate cancer cell invasiveness. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:108–117. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez-Cambronero J, Henkels KM. Cloning of PLD2 from baculovirus for studies in inflammatory responses. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;861:201–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-600-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macindoe G, Mavridis L, Venkatraman V, Devignes MD, Ritchie DW. HexServer: an FFT-based protein docking server powered by graphics processors. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:W445–449. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritchie DW, Kemp GJ. Protein docking using spherical polar Fourier correlations. Proteins. 2000;39:178–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaaf G, Ortlund EA, Tyeryar KR, Mousley CJ, Ile KE, Garrett TA, Ren J, Woolls MJ, Raetz CR, Redinbo MR, Bankaitis VA. Functional anatomy of phospholipid binding and regulation of phosphoinositide homeostasis by proteins of the sec14 superfamily. Molecular cell. 2008;29:191–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlach J, Saad JS. Trio engagement via plasma membrane phospholipids and the myristoyl moiety governs HIV-1 matrix binding to bilayers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:3525–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216655110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kono N, Ohto U, Hiramatsu T, Urabe M, Uchida Y, Satow Y, Arai H. Impaired alpha-TTP-PIPs interaction underlies familial vitamin E deficiency. Science. 2013;340:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1233508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JH, Ohba M, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Novel functions of the phospholipase D2-Phox homology domain in protein kinase Czeta activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3194–3208. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3194-3208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee HY, Jung H, Jang IH, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Cdk5 phosphorylates PLD2 to mediate EGF-dependent insulin secretion. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1787–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang IH, Lee S, Park JB, Kim JH, Lee CS, Hur EM, Kim IS, Kim KT, Yagisawa H, Suh PG, Ryu SH. The direct interaction of phospholipase C-gamma 1 with phospholipase D2 is important for epidermal growth factor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18184–18190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng HJ, Henkels KM, Mahankali M, Dinauer MC, Gomez-Cambronero J. Evidence for two CRIB domains in phospholipase D2 (PLD2) that the enzyme uses to specifically bind to the small GTPase Rac2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16308–16320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henkels KM, Peng HJ, Frondorf K, Gomez-Cambronero J. A comprehensive model that explains the regulation of phospholipase D2 activity by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2251–2263. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01239-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colley WC, Altshuller YM, Sue-Ling CK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Branch KD, Tsirka SE, Bollag RJ, Bollag WB, Frohman MA. Cloning and expression analysis of murine phospholipase D1. Biochem J. 1997;326 (Pt 3):745–753. doi: 10.1042/bj3260745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakashima S, Matsuda Y, Akao Y, Yoshimura S, Sakai H, Hayakawa K, Andoh M, Nozawa Y. Molecular cloning and chromosome mapping of rat phospholipase D genes, Pld1a, Pld1b and Pld2. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;79:109–113. doi: 10.1159/000134694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kodaki T, Yamashita S. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel phospholipase D complementary DNA from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11408–11413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez I, Arnold RS, Lambeth JD. Cloning and initial characterization of a human phospholipase D2 (hPLD2). ADP-ribosylation factor regulates hPLD2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12846–12852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chae YC, Kim KL, Ha SH, Kim J, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Protein kinase Cdelta-mediated phosphorylation of phospholipase D controls integrin-mediated cell spreading. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5086–5098. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00443-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sung TC, Zhang Y, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. Structural analysis of human phospholipase D1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3659–3666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Fulvio M, Lehman N, Lin X, Lopez I, Gomez-Cambronero J. The elucidation of novel SH2 binding sites on PLD2. Oncogene. 2006;25:3032–3040. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Fulvio M, Frondorf K, Gomez-Cambronero J. Mutation of Y179 on phospholipase D2 (PLD2) upregulates DNA synthesis in a PI3K-and Akt-dependent manner. Cell Signal. 2008;20:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leiros I, McSweeney S, Hough E. The reaction mechanism of phospholipase D from Streptomyces sp. strain PMF. Snapshots along the reaction pathway reveal a pentacoordinate reaction intermediate and an unexpected final product. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leiros I, Secundo F, Zambonelli C, Servi S, Hough E. The first crystal structure of a phospholipase D. Structure. 2000;8:655–667. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gottlin EB, Rudolph AE, Zhao Y, Matthews HR, Dixon JE. Catalytic mechanism of the phospholipase D superfamily proceeds via a covalent phosphohistidine intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9202–9207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siddiqi AR, Srajer GE, Leslie CC. Regulation of human PLD1 and PLD2 by calcium and protein kinase C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1497:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sciorra VA, Rudge SA, Wang J, McLaughlin S, Engebrecht J, Morris AJ. Dual role for phosphoinositides in regulation of yeast and mammalian phospholipase D enzymes. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:1039–1049. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sciorra VA, Rudge SA, Prestwich GD, Frohman MA, Engebrecht J, Morris AJ. Identification of a phosphoinositide binding motif that mediates activation of mammalian and yeast phospholipase D isoenzymes. Embo J. 1999;18:5911–5921. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peng HJ, Henkels KM, Mahankali M, Marchal C, Bubulya P, Dinauer MC, Gomez-Cambronero J. The Dual Effect of Rac2 on Phospholipase D2 Regulation That Explains both the Onset and Termination of Chemotaxis. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2227–2240. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01348-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mendez R, Leplae R, Lensink MF, Wodak SJ. Assessment of CAPRI predictions in rounds 3–5 shows progress in docking procedures. Proteins. 2005;60:150–169. doi: 10.1002/prot.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bunney TD, Opaleye O, Roe SM, Vatter P, Baxendale RW, Walliser C, Everett KL, Josephs MB, Christow C, Rodrigues-Lima F, Gierschik P, Pearl LH, Katan M. Structural insights into formation of an active signaling complex between Rac and phospholipase C gamma 2. Molecular cell. 2009;34:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhong M, Shen Y, Zheng Y, Joseph T, Jackson D, Foster DA. Phospholipase D prevents apoptosis in v-Src-transformed rat fibroblasts and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:615–619. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng Y, Rodrik V, Toschi A, Shi M, Hui L, Shen Y, Foster DA. Phospholipase D couples survival and migration signals in stress response of human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15862–15868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao Y, Ehara H, Akao Y, Shamoto M, Nakagawa Y, Banno Y, Deguchi T, Ohishi N, Yagi K, Nozawa Y. Increased activity and intranuclear expression of phospholipase D2 in human renal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:140–143. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshida M, Okamura S, Kodaki T, Mori M, Yamashita S. Enhanced levels of oleate-dependent and Arf-dependent phospholipase D isoforms in experimental colon cancer. Oncol Res. 1998;10:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wakelam MJ, Martin A, Hodgkin MN, Brown F, Pettitt TR, Cross MJ, De Takats PG, Reynolds JL. Role and regulation of phospholipase D activity in normal and cancer cells. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1997;37:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(96)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.