Abstract

Pharmacological and behavioral interventions have focused on reducing tic severity to alleviate tic-related impairment for youth with chronic tic disorders (CTDs), with no existing intervention focused on the adverse psychosocial consequences of tics. This study examined the preliminary efficacy of a modularized cognitive behavioral intervention ("Living with Tics", LWT) in reducing tic-related impairment and improving quality of life relative to a waitlist control of equal duration. Twenty-four youth (ages 7–17 years) with Tourette Disorder or Chronic Motor Tic Disorder and psychosocial impairment participated. A treatment-blind evaluator conducted all pre- and post-treatment clinician-rated measures. Youth were randomly assigned to receive the LWT intervention (n=12) or a 10-week waitlist (n=12). The LWT intervention consisted of up to 10 weekly sessions targeted at reducing tic-related impairment and developing skills to manage psychosocial consequences of tics. Youth in the LWT condition experienced significantly reduced clinician-rated tic-impairment, and improved child-rated quality of life. Ten youth (83%) in the LWT group were classified as treatment responders compared to four youth in the waitlist condition (33%). Treatment gains were maintained at one-month follow-up. Findings provide preliminary data that the LWT intervention reduces tic-related impairment and improves quality of life for youth with CTDs.

Keywords: cognitive behavior therapy, functional impairment, treatment outcome, quality of life, chronic tic disorders, Tourette Disorder

1. Introduction

Tourette Disorder and other chronic tic disorders (hereafter collectively referred to as CTDs) are neuropsychiatric conditions characterized by the presence of motor and/or phonic tics lasting at least a year. Approximately 0.3%–0.8% of youth are estimated to be affected by CTDs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Although tics are the hallmark symptom of CTDs, youth with CTDs regularly present with co-occurring psychiatric conditions [e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), non-OCD anxiety disorders; Freeman et al., 2000; Specht et al., 2011; Lebowitz et al., 2012], social and emotional difficulties (Carter et al., 2000; Tabori Kraft et al., 2012; McGuire et al., 2013) and disruptive behaviors (Sukhodolsky et al., 2003; Tabori Kraft et al., 2012). Youth with CTDs experience significant impairment (Conelea et al., 2011) that often affects multiple domains of functioning (Storch et al., 2007a). Indeed, relative to their peers, youth with CTDs report a diminished quality of life (Storch et al., 2007b; Eddy et al., 2011b).

In response to the impairment and diminished quality of life reported by many youth with CTDs, interventions have focused on alleviating tic severity. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of typical and atypical antipsychotic medications (e.g., haloperidol, risperidone) has demonstrated their efficacy in reducing tic symptom severity compared to placebo (Weisman et al., 2012). Although efficacious, these medications are frequently accompanied by side effects that may limit tolerability and acceptability (Scahill et al., 2006a). Similarly, a meta-analysis of RCTs of alpha-2 agonists medications (e.g., guanfacine, clonidine) demonstrated their efficacy in reducing tic symptom severity, albeit with modest results (Weisman et al., 2012). Behavior therapy (e.g., habit reversal training, comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics) has also demonstrated efficacy in reducing tic symptom severity in RCTs for youth and adults (Piacentini et al., 2010; Himle et al., 2012; Wilhelm et al., 2012), with a meta-analysis of behavior therapy RCTs identifying comparable treatment effects to antipsychotic medications (McGuire et al., 2014).

Although pharmacological and behavioral interventions both demonstrate efficacy in alleviating tic symptom severity, these treatments primarily focus on tic severity reduction predicated on the assumption that tic severity is wholly responsible for the impairment and diminished quality of life experienced by youth with CTDs. Despite this assumption, the interplay between tic severity, impairment, and quality of life remains unclear among youth with CTDs. For instance, several reports have identified a modest association between tic severity and quality of life (Storch et al., 2007b; Cutler et al., 2009), whereas others have failed to find a significant relationship (Bernard et al., 2009; Eddy et al., 2011a). This ambiguous relationship is further complicated by research suggesting that co-occurring OCD and ADHD (Eddy et al., 2012), depressive symptoms (Muller-Vahl et al., 2010), negative self-perception (Khalifa et al., 2010; Eddy et al., 2011b), and social deficits (McGuire et al., 2013) can negatively impact quality of life for individuals with CTD. Indeed the relationship between tic severity and quality of life may be more nuanced as many youth with CTDs experience problems secondary to their tics (e.g., social interference, discrimination, peer victimization; Storch et al., 2007c; Conelea et al., 2011; Zinner et al., 2012) that can impact domains central to their quality of life to varying degrees.

Although many individuals with CTDs report that tics subside in early adulthood (Bloch et al., 2006), tics often do not remit entirely and, at the least, a child must endure them for many years. Similarly, evidence-based treatments yield significant reductions in tic severity, but infrequently result in tic remission. Thus, youth with CTDs have to develop effective coping strategies for tics even when receiving evidence-based treatment. While experts acknowledge that tics can have adverse psychosocial consequences that may endure even after tics diminish and/or remit (Scahill et al., 2013), there has been limited research on helping youth with CTDs develop skills to cope with these psychosocial consequences. Indeed, when adults with CTDs were surveyed about their experiences, many stated that they continued to feel different from peers because of their tics, relied on social avoidance to manage tics, experienced social impairment, and believed that tics contributed to other psychological problems (Conelea et al., 2013). Thus, adults with CTDs continue to experience considerable adverse psychosocial consequences associated with tics that likely started in childhood. Therefore, interventions are needed for youth that not only reduce tic symptom severity, but also provide skills to manage the adverse psychosocial problems associated with tics (Peterson and Cohen, 1998). Targeted interventions may mitigate the impairment caused by tics, positively impact quality of life during childhood and adolescence, and curtail social difficulties into adulthood.

Although co-occurring problems are recognized as an important aspect of treatment in evidence-based practice parameters (Murphy et al., 2013), few treatment protocols have attempted to target co-occurring problems among youth with CTDs (Scahill et al., 2006b; Sukhodolsky et al., 2009), and have not directly addressed the psychosocial challenges associated with tics themselves. To date, only a single open-label case series has examined an intervention to address associated negative social consequences of tics in youth with CTD. Storch and colleagues developed a modular cognitive behavioral intervention called Living with Tics (LWT) and found that it reduced tic-related impairment, improved psychosocial functioning, and increased quality of life among eight youth with CTDs (Storch et al., 2012). This therapeutic approach is important because it addresses aspects of treatment not directly targeted by existing pharmacological or behavioral interventions, and can serve as either a primary or adjunctive component of existing evidence-based interventions.

The current study extended up the preliminary findings by Storch et al. (2012) by incorporating additional modules into the LWT intervention and evaluating its efficacy relative to a waitlist condition of equal duration in a randomized controlled pilot trial. We hypothesized that the LWT intervention would be superior to the waitlist condition in reducing clinician-rated tic impairment and improving quality of life for youth with CTDs. Secondary aims explored the effects of the LWT intervention on tic symptom severity, obsessive-compulsive symptom severity, and anxiety symptom severity relative to the waitlist condition.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

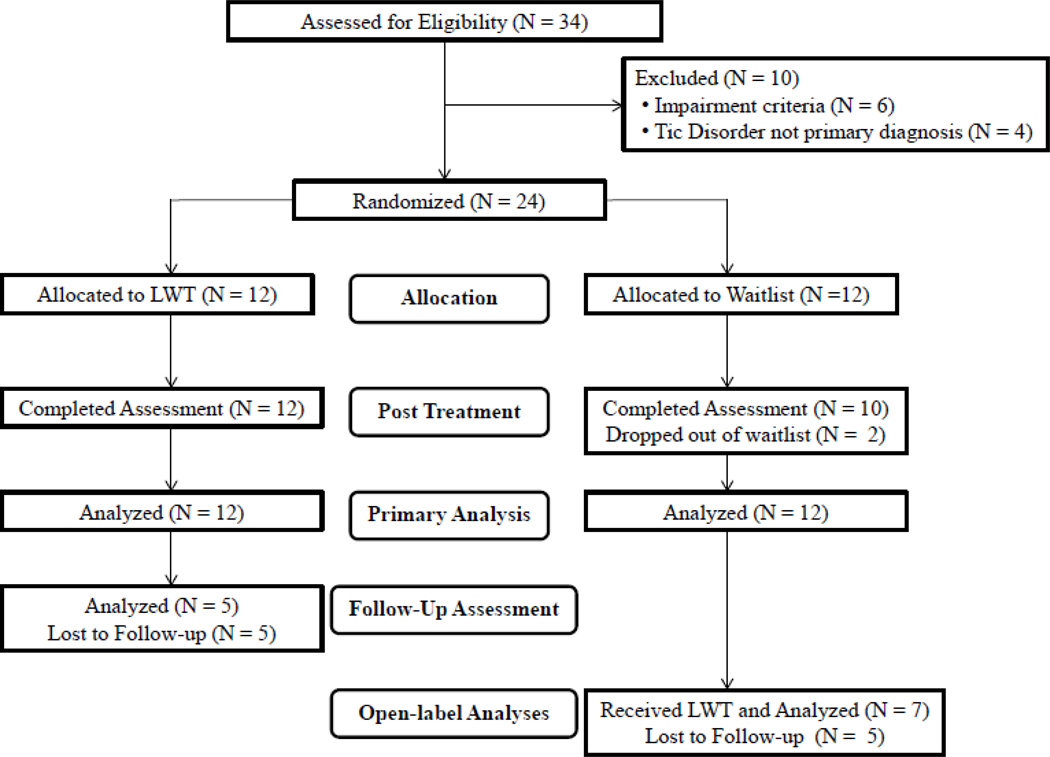

Thirty-four youth and their parents were invited to participate in this study. Youth were recruited from the normal clinic flow within an outpatient OCD and CTD specialty clinic in the southeastern United States. Study inclusion criteria required that youth: 1) have a principal diagnosis of CTD; 2) be between 7 and 17 years of age; 3) have a Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS; Leckman et al., 1989) Total Impairment score ≥ 20 and a YGTSS Total Tic Severity score ≥ 10; 4) be English speaking; 5) have at least one parent be available to attend relevant sessions; and 6) be medication-free or on a stable dose of medication for at least eight weeks prior to treatment. Youth were excluded from participation for the following reasons: 1) presence of comorbid psychosis, bipolar disorder, autistic disorder, or current suicidal intent; 2) presence of an untreated primary psychiatric condition that warranted more immediate treatment (e.g., OCD, ADHD); and 3) were receiving another psychological intervention. Tic disorder diagnoses were confirmed via a clinical interview with a child and adolescent clinical psychologist or psychiatrist experienced with CTD, and administration of the YGTSS by a trained clinician. Co-occurring diagnoses were determined via the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-DSM-IV-Child and Parent Version (Silverman and Albano, 1996). Twenty-four youth met inclusion criteria, and participated in the study. A CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1, and a summary of participant characteristics is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study, LWT indicates Living with Tics treatment protocol.

Table 1.

Pre-treatment Sample Characteristics

| Total Sample (N = 24) |

LWT Group (N = 12) |

Waitlist (N = 12) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | χ2 | p | |

| Male | 18 (75%) | 7 (58%) | 11 (92%) | Fisher's exact | 0.16 |

| On a tic medicationa | 13 (54%) | 6 (50%) | 7 (58%) | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| Comorbid Diagnosesb | |||||

| ADHD | 10 (42%) | 4 (33%) | 6 (50%) | 0.69 | 0.41 |

| OCD | 9 (38%) | 4 (33%) | 5 (42%) | Fisher's exact | 1.00 |

| Non-OCD Anxiety Disorderc | 17 (71%) | 8 (67%) | 9 (75%) | Fisher's exact | 1.00 |

| Depressive Disorder | 3 (13%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (17%) | Fisher's exact | 1.00 |

| Disruptive Behavior Disorder | 5 (21%) | 4 (33%) | 1 (8%) | Fisher's exact | 0.32 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t | p | |

| Age | 11.34 (2.68) | 11.71 (2.80) | 10.97 (2.61) | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| Tic Symptom Severity | |||||

| CGI-Tic Severity | 3.17 (0.82) | 3.00 (0.60) | 3.33 (0.98) | −1.00 | 0.33 |

| YGTSS Total Tic Score | 22.42 (7.80) | 20.17 (8.81) | 24.67 (6.21) | −1.45 | 0.16 |

| Tic Impairment | |||||

| YGTSS Impairment Score | 29.58 (7.51) | 27.50 (7.54) | 31.37 (7.18) | −1.39 | 0.18 |

| CTIM-P Tic Impairment Score | 21.23 (18.03) | 18.38 (15.13) | 24.09 (20.81) | −0.77 | 0.45 |

| Co-Occurring Symptom Severity | |||||

| CY-BOCS Total Score | 11.17 (7.39) | 11.25 (8.16) | 11.08 (6.91) | 0.05 | 0.96 |

| MASC Total Score T-Scored | 44.17 (9.57) | 41.27 (8.79) | 46.83 (9.84) | −1.42 | 0.17 |

| Quality of Life | |||||

| PedsQL Total Score | 76.68 (15.76) | 73.91 (14.90) | 79.44 (16.76) | −0.85 | 0.40 |

Note: ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, YGTSS = Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, CTIM-P = Child Tourette Impairment Scale-Parent report, CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory,

Tic influencing medications included antipsychotics and alpha-2 agonists

Some youth had more than one comorbid diagnosis

Does not include specific phobias

Missing one form for patients.

2.2 Measures

Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS; Leckman et al., 1989)

The YGTSS is a clinician-rated semi-structured interview with demonstrated reliability and validity that measures tic symptom severity over the previous week (Leckman et al., 1989; Storch et al., 2005). The YGTSS produces a Total Tic Score (range: 0–50), and a Total Impairment Score (range: 0–50), with higher rating indicating greater tic severity and impairment, respectively.

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children-DSM-IV: Child and Parent Version (ADIS-IV-C/P; Silverman and Albano, 1996)

The ADIS-C/P is a clinician-administered structured diagnostic interview based on DSM-IV criteria. Diagnoses reflect endorsement of symptoms, as well as a severity rating (patient impairment/distress) of at least four on a 0–8 scale. The ADIS-C/P has demonstrated strong psychometric properties including test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and concurrent validity (Silverman et al., 2001; Wood et al., 2002).

Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-Severity; Guy, 1976)

The CGI-Severity is a 7-point clinician rating of illness severity that ranges from no illness (0) to extremely severe illness (6). The CGI-Severity served as an overall measure of tic severity and tic-related impairment experienced by youth. The CGI-Severity has been widely used in RCTs of youth with CTDs (Piacentini et al., 2010; Himle et al., 2012).

Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-Improvement; Guy, 1976)

The CGI-Improvement is a clinician-rated measure of improvement that is rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very much worse (0) to very much improved (6). The CGI-Improvement was administered at the post-treatment (or post-waitlist) assessment by an independent evaluator blind to treatment condition. The CGI-Improvement is well validated in treatment studies of CTDs (Storch et al., 2011; Jeon et al., 2013), with a rating of either "very much improved" or "much improved" corresponding with a positive response to treatment.

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS; Scahill et al., 1997)

The CY-BOCS is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview used to assess obsessive compulsive symptom severity over the past week, with total severity scores ranging betweeen 0–40. The CY-BOCS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties and sensitivity to treatment (Scahill et al., 1997; Storch et al., 2004).

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-Child Version (PedsQL; Varni et al., 2003)

The PedsQL version is a 23-item child-rated measure that assessed youth’s quality of life. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores corresponding to better quality of life. The PedsQL Total Score provides a metric of overall child-rated quality of life. Extensive validity and reliability data have been published across multiple clinical presentations in support of the PedsQL (e.g., Varni and Burwinkle, 2006; Lack et al., 2009).

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al., 1997)

The MASC is a psychometrically sound 39-item child-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of general, social, and separation anxiety in youth (March et al., 1997). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-scale that ranges from never true (0) to often very true about me (3). The MASC items sum to produce a total score that serves as an index of anxiety symptom severity.

Child Tourette’s Syndrome Impairment Scale (CTIM-P; Storch et al., 2007a)

The CTIM-P is a 37-item parent-rated instrument that includes school, home, and social activities that may be impaired by tics or other related problems. The CTIM-P produces a total tic impairment score, which has demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity (Storch et al., 2007a).

Satisfaction with Services (SS; Hawley and Weisz, 2005)

The SS is a 5-item instrument that assesses parents’ and youths’ satisfaction with therapeutic services (e.g., “Overall, how satisfied were you with the help that your child received at this clinic?”). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert-type scale that ranges from one (very false/very unsatisfied) to five (very true/very satisfied). Total scores range from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater treatment satisfaction.

2.3 Procedures

The local Institutional Review Board approved study procedures. At the screening assessment, written consent and assent were obtained from parents and youth respectively. Afterwards, a trained independent evaluator administered clinician-administered ratings (YGTSS, ADIS-C/P, CGI-Severity, CY-BOCS). Subsequently, youth (PedsQL, MASC) and parents (CTIM-P) completed their respective rating scales. If participants met inclusion criteria, they were randomly assigned on a 1:1 basis to either immediate treatment or a 10-week waitlist. Participants who received treatment immediately were invited back within a week to begin LWT. Participants could receive up to 10 sessions over the 10 week period (1 session per week), but were not required to utilize all 10 sessions prior to the post-treatment assessment. Approximately 10 weeks after their initial assessment, participants were re-evaluated using the same assessment battery by an independent evaluator blind to treatment condition. For those participants who received treatment immediately and were considered to be treatment responders on the CGI-Improvement, a follow-up assessment was completed approximately one month after the post-treatment assessment to examine the short-term durability of treatment gains. Participants assigned to the 10-week waitlist condition were offered LWT, and completed a post-treatment assessment (n=7) that consisted of the same assessment battery.

2.4 Independent Evaluator Training and Reliability

Independent evaluators were trained clinicians who had experience working with youth with CTDs. Evaluator training involved instructional meetings, in vivo observations, and direct supervision provided by an experienced clinical psychologist. All clinician-administered interviews were audio recorded for quality assurance purposes. Inter-rater reliability of the YGTSS was completed either by listening to audio recordings of assessment and/or completing independent YGTSS ratings in vivo during assessments. Six assessments (25%) were randomly selected from each assessment point (pre-treatment, post-treatment), and independently rated by two additional raters. Excellent inter-rater reliability was found across raters for both the YGTSS Total Tic Score (ICC=0.99, 95% CI: 0.98, 0.99) and YGTSS Total Impairment Score (ICC=0.98, 95% CI: 0.94, 0.99).

2.5 Treatment Protocol

The LWT treatment protocol was initially developed by Storch et al. (2012) and was updated to include the additional modules of parent-training and emotion regulation for this current protocol (see Storch et al., 2012 for further information about treatment module development). The LWT intervention consisted of 10 modules delivered in weekly 50-minute sessions (see Table 2). This modular approach was explicitly designed to individualize each youth's treatment within the context of empirically-derived treatment modules. Modules could be used for more than one treatment session (with the noted exception of psychoeducation and relapse prevention) and could be used interchangeably to address youth's most pressing problems over the course of treatment. In Session 1 (psychoeducation), the therapist oriented participants to treatment and assessed the impact of tics on youth's lives. The therapist focused on the initial problem area identified as most important by parents and youth, but was allowed to redirect treatment based on clinical presentation. For instance, if treatment initially focused on habit reversal training (HRT), but disruptive behaviors interfered with HRT implementation, the therapist could use the parent training for disruptive behaviors module to provide parents with the tools to manage disruptive behaviors, and then return to HRT when the problematic behavior was resolved. Similarly, if treatment focused on overcoming tic-related avoidance, but peer teasing was reported to be an immediate problem that week, the therapist could use the coping with tics at school module to help the youth deal with immediate peer teasing, and then return to overcoming tic-related avoidance when the situation was resolved.

Table 2.

Overview of the Modular Intervention

| Focus of Module | Key Elements |

|---|---|

| Psychoeducation |

|

| Abbreviated Habit Reversal Training |

|

| Feeling Identification & Cognitive Restructuring |

|

| Problem Solving |

|

| Parent Training for Disruptive Behaviors |

|

| Emotion Regulation and Anger Management |

|

| Overcoming Tic-Related Avoidance |

|

| Talking About Tics & Coping at School |

|

| Improving Self-Esteem |

|

| Relapse Prevention |

|

Treatment modules included abbreviated HRT (Mode=2 sessions, Range: 1–3), cognitive restructuring (Mode=0 sessions, Range: 0–2), problem solving (Mode=0 sessions, Range: 0–5), parent training (Mode=0 sessions, Range: 0–3), emotion regulation (Mode=0 sessions, Range: 0–2), overcoming tic-related avoidance (Mode=0 sessions, Range: 0–1), talking about tics with peers and coping at school (Mode=1 session, Range: 0–2), and improving self-esteem (Mode=0 sessions, Range: 0–2). Although therapists were instructed to limit abbreviated HRT to two sessions, one participant received three sessions of HRT due to clinical indication.

Treatment was provided by post-doctoral level psychologists and advanced clinical psychology doctoral students. Therapists were supervised by an experienced clinical psychologist between treatment sessions. All therapy sessions were audio-taped for quality assurance purposes. Fidelity ratings to the treatment manual were made on 20% of randomly selected sessions. Sessions were rated for adherence to the treatment manual and overall session quality using detailed forms developed for the study. Scores for adherence and session quality ratings ranged from “no adherence/poor quality” (0) to “excellent adherence/excellent quality” (5). Adherence (M=4.59, SD=0.67) and quality ratings (M=4.59, SD=0.67) indicated that therapist adherence to the treatment manual and overall session quality was good to excellent.

2.6 Analytic Plan

A series of chi-square and t-tests assessed pre-treatment between group differences, with Fisher exact tests being used when cell sizes were less than five for categorical variables. Analyses of pre- and post-treatment data were based on intent-to-treat principles (ITT), with last observation carried forward used to account for missing post-treatment data for two participants lost to follow-up. As a precautionary step, completer analyses were also conducted to determine if outcomes differed by analytic approach. Findings were consistent between ITT and completer analyses for continuous measures; thus, only the former is reported as it is more conservative. Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous measures. Using two groups (LWT and waitlist) and the two time points (pre-treatment versus post-treatment), an ANOVA tested for a significant interaction between treatment group and time. The effect size (ES) for continuous measures was calculated using Cohen's d. The rates of positive response on the CGI-Improvement were evaluated using χ2 tests. Change between the post-treatment and the follow-up assessment for treatment responders in the LWT group was examined using paired t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests. As youth who completed the waitlist condition also received LWT, an open-trial analysis was conducted wherein outcome data were collapsed across treatment arms (12 LWT, 7 WL). Paired samples t-tests were performed to compare pre-treatment and post-treatment scores for all youth who received the LWT intervention (n=19). Given the exploratory nature of this intervention, significance was set at p=0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Participant and Treatment Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics for each group are presented in Table 1. Participants in the LWT and waitlist conditions did not significantly differ on demographics, clinical characteristics, or tic medication status. Twenty-two of the 24 participants (92%) completed pre-treatment and post-treatment study procedures. Two participants in the waitlist condition were lost to follow-up (e.g., unable to be reached), and did not complete the post-waitlist assessment. Participants randomized to the LWT group received an average of eight sessions of therapy over the treatment period (range: 6–10 sessions).

3.2 LWT versus Waitlist

The mean YGTSS Total Impairment Score decreased from 27.50 ±7.54 at pre-treatment to 8.33 ±8.35 at post-treatment in the LWT group, and from 31.67 ±7.18 to 23.75 ±8.82 in the waitlist group. This 70% reduction in clinician-rated tic impairment on the YGTSS was significantly greater than the 25% reduction in the waitlist group, and falls within the range of a large treatment effect (p=0.01, ES=1.50, see Table 3). Youth in the LWT group also experienced a greater improvement in quality of life (PedsQL) relative to youth in the waitlist condition (p=0.03, ES=0.72, see Table 3). On the CGI-Improvement, 10 of the 12 participants (83%) in the LWT condition were rated as treatment responders compared to four of 12 participants (33%) in the waitlist condition (χ2 =6.17, p=0.013).

Table 3.

Pre-and Post-Treatment scores for the Living with Tic and Waitlist Groups Using Last Observation Carried Forward

| Living with Tics (N =12) | Waitlist (N = 12) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure |

Pre- treatment Mean (SD) |

Post- Treatment Mean (SD) |

Pre- treatment Mean (SD) |

Post- Treatment Mean (SD) |

F- Test |

p | ES |

| Tic Symptom Severity & Impairment | |||||||

| YGTSS Impairment Score | 27.50 (7.54) | 8.33 (8.35) | 31.67 (7.18) | 23.75 (8.82) | F1, 22 = 7.38 | 0.01 | 1.50 |

| YGTSS Total Tic Score | 20.17 (8.81) | 14.33 (8.92) | 24.67 (6.21) | 24.75 (8.60) | F1, 22 = 1.89 | 0.18 | 0.76 |

| CTIM-P Tic Impairment Score | 18.38 (15.13) | 9.87 (9.56) | 24.09 (20.81) | 13.06 (11.92) | F1, 22 = 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.14 |

| Co-Occurring Symptom Severity | |||||||

| CY-BOCS Total Score | 11.25 (8.16) | 5.83 (7.72) | 11.08 (6.91) | 10.17 (7.96) | F1, 22 = 3.91 | 0.06 | 0.61 |

| MASC Total Score T-Score | 41.27 (8.79) | 37.55 (8.12) | 46.83 (9.84) | 45.08 (9.57) | F1, 21 = 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.21 |

| Quality of Life | |||||||

| PedsQL Total Score | 73.91 (14.90) | 83.61 (12.01) | 79.44 (16.76) | 77.81 (19.75) | F1, 22 = 5.33 | 0.03 | 0.72 |

Note: YGTSS = Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, CTIM-P = Child Tourette Impairment Scale-Parent report, CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, Peds QL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

When examining secondary outcomes, a large reduction in the YGTSS Total Tic Score was observed for the LWT group relative to the waitlist group (ES=0.76), however it did not reach statistical significance (p=0.18, see Table 3). Similarly, youth in the LWT group exhibited improvement on other secondary outcomes in comparison to the waitlist condition (ES=0.10–0.76), however these differences were not significant (see Table 3). For the 12 youth in the LWT group, the mean parental satisfaction following the intervention was 24.50 (SD=0.67), and mean child satisfaction was 24.08 (SD=1.93), suggesting that both youth and their parents were satisfied with the intervention.

3.3 Follow-up Assessment

Five of the 10 treatment responders on the CGI-Improvement completed a follow-up assessment (M=6weeks, SD=2weeks). The reductions in tic-related impairment in the LWT group were maintained at follow-up. The follow-up YGTSS Total Impairment Scores (M=10.00, SD=0.00) were not significantly different from the post-treatment scores (t4=0.00, p=1.00). Furthermore, no significant change was observed between post-treatment scores and follow-up scores on child-rated quality of life (t4=0.41, p=0.71). All follow-up assessment completers (100%) continued to respond to treatment on the CGI-Improvement (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00). Paired samples t-tests found no significant differences between post-treatment scores and follow-up scores on the YGTSS Total Tic Score (p=0.73), CY-BOCS (p=0.08), MASC Total T-score (p=0.68), and CTIM-P Tic Impairment (p=0.41).

3.4 Open-Trial Analyses

Youth in the waitlist group who completed the post-waitlist assessment were offered LWT (n=10). Seven youth in the waitlist condition received LWT and completed a post-treatment assessment. An open-trial analysis was conducted wherein outcome data were collapsed across treatment arms (12 LWT, 7 WL) to examine effects of the intervention. Participants in these open-label analyses (n=19) collectively received an average of nine therapy sessions over the 10-week period (range: 6–10 sessions). Paired sample t-tests comparing pre-treatment to post-treatment scores revealed that youth receiving LWT exhibited a 60% reduction on the YGTSS Total Impairment score (p<0.001, ES=1.21, see Table 4). These youth also reported experiencing an improved quality of life (p<0.01, ES=0.76), with 16 out of the 19 participants (84%) being considered a treatment responder on the CGI-Improvement. Youth receiving LWT experienced a 30% reduction on the YGTSS Total Tic Score (p=0.03, ES=0.54), and also exhibited significant improvement on the CY-BOCS (p<0.001, ES=0.86), MASC Total T-score (p<0.03, ES=0.58), and CTIM-P Tic Impairment (p<0.001, ES=0.91). For the 19 youth who received treatment, the mean parental satisfaction following the LWT intervention was 24.61 (SD=0.61), and mean child satisfaction was 24.06 (SD=1.89), suggesting that both youth and their parents were satisfied with the intervention.

Table 4.

Open Label Pre-and Post-Treatment scores for Participants who completed LWT Treatment

| Living with Tics (N =19) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure |

Pre-treatment Mean (SD) |

Post-Treatment Mean (SD) |

Paired T- Test |

p | ES |

| Tic Symptom Severity & Impairment | |||||

| YGTSS Impairment Score | 26.32 (7.61) | 10.53 (9.11) | 5.28 | < 0.001 | 1.21 |

| YGTSS Total Tic Score | 21.79 (9.13) | 16.11 (9.47) | 2.33 | 0.031 | 0.54 |

| CTIM-P Tic Impairment Score | 16.97 (13.77) | 7.71 (8.35) | 3.95 | 0.001 | 0.91 |

| Co-Occurring Symptom Severity | |||||

| CY-BOCS Total Score | 12.16 (7.85) | 6.05 (7.55) | 3.75 | 0.001 | 0.86 |

| MASC Total Score T-Score | 43.78 (9.38) | 40.22 (10.41) | 2.45 | 0.026 | 0.58 |

| Quality of Life | |||||

| PedsQL Total Score | 73.34 (17.29) | 82.89 (13.09) | −3.29 | 0.004 | 0.76 |

Note: YGTSS = Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, CTIM-P = Child Tourette Impairment Scale-Parent report, CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, Peds QL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

4. Discussion

The present study examined the preliminary efficacy of a cognitive behavioral intervention to reduce tic-related impairment and improve quality of life for youth with CTDs. Although previous pharmacological and behavioral interventions have emphasized reduction in tic severity, the present intervention focused on providing youth and their parents with skills to deal with tic-related problems and negative psychosocial consequences associated with tics. The LWT intervention significantly reduced clinician-rated tic-related impairment (ES=1.50) and improved child-reported quality of life (ES=0.72) relative to a waitlist condition. Aside from experiencing therapeutic benefit, participating parents and youth found this intervention to be highly satisfactory. Youths' improvement during acute treatment was maintained at the follow-up assessment for the subsample of responders who completed the assessment. Collectively, results from this pilot trial suggest that the LWT intervention is associated with reduced tic-related impairment, improved quality of life, and high satisfaction.

These findings may be understood in several ways. First, the LWT intervention primarily focused on reducing tic-related impairment and problems associated with tics among youth with CTDs instead of directly targeting tic symptom severity. This is different from current evidence-based behavioral interventions that focus on reducing tic symptom severity as a means to reduce impairment and improve functioning. Indeed, behavior therapy for youth with CTD has moderate-to-large treatment effects for tic severity (0.68) and tic-related impairment (0.57) (Piacentini et al., 2010). Comparatively, this intervention emphasized the development of skills for youth and their parents to deal with problems that accompany tics (e.g., social interference, peer teasing, regulating emotions and behaviors, self-esteem). As parents and youth developed improved skills, they could directly address both problematic tic symptoms and associated problems using adaptive strategies. For instance, social avoidance due to tic symptoms is common (Conelea et al., 2011); in the LWT intervention, youth learned skills to manage tics during social activities (e.g., competing responses, coping strategies) and practiced overcoming tic-related avoidance in a step-wise fashion. Concurrently, parents were instructed to limit their accommodation of youth's tic-related avoidance, thereby providing youth with the opportunity to practice their improved skills. While the LWT intervention targeted reductions in tic-related impairment, it is important to note that treatment also incorporated active instruction on HRT to help youth and parents learn to manage tics. Collectively, this individualized treatment package yielded a moderate reduction in tic symptom severity that falls within the range of full trials of behavior therapy (Piacentini et al., 2010), but had smaller treatment effects on tic symptom severity in open-label analyses in which the sample size was larger. Thus, LWT's treatment effects on tic severity may be more modest in a larger RCT. Although direct comparisons between the LWT and behavior therapy cannot be inferred in the absence of a head-to-head trial, these findings suggest that LWT can yield moderate-to-large treatment effects for tic severity and tic-related impairment. While there may be some impetus to conduct such a head-to-head trial, it would not prove clinically relevant as these two interventions may be combined in clinical practice.

Second, youth in the LWT group experienced a significant improvement in their quality of life. While medications and behavioral interventions are efficacious in reducing tic symptom severity, quality of life may remain impaired due to the presence of sustained poor coping strategies (e.g., social avoidance) that continue to impact social, emotional and school functioning (Conelea et al., 2011; Conelea et al., 2013). Although many youth respond to pharmacological and behavioral interventions for CTDs (Murphy et al., 2013), remission is rare and even treatment responders continue to experience tics. Thus, the LWT intervention presents a unique opportunity to help youth with CTDs develop effective tools to manage their tics and associated problems, which is hypothesized to positively affect their quality of life. While this study examined the LWT intervention as a stand-alone treatment, it may also serve as an adjunctive treatment to either pharmacological and/or behavioral interventions. For instance, for youth who receive an evidence-based intervention but do not achieve desired reductions in tic-related impairment or improvement in quality of life, their treatment may be supplemented with relevant LWT modules to develop skills to effectively manage tic-related problems and navigate the adverse psychosocial consequences of remaining tics. Alternatively, given the overlap between current behavior therapy protocols (Woods et al., 2008) and modules covered in LWT (e.g., psycho-education, HRT, relapse prevention), an integrative approach may be used whereby the two treatments are combined. For example, a clinician may interweave HRT with LWT modules to reduce tic severity and tic-related impairment, and improve youth's quality of life in an individualized and empirically-informed method. While this integrative approach would likely require more sessions than originally intended by either treatment protocol (8–10 sessions), 15 treatment session (or fewer) is a standard figure for cognitive behavioral treatments among related disorders (e.g., OCD; March and Mulle, 1998).

Lastly, the LWT intervention was rated as highly satisfactory by parents and youth. This high level of satisfaction suggests that the LWT intervention is well tolerated by both youth and parents, and adequately addressed their needs. This is a notable contrast from existing pharmacological interventions for CTD that may be accompanied by adverse side effects that can limit tolerability (Scahill et al., 2006a; Correll et al., 2009). This high satisfaction observed in the LWT group may serve to limit treatment attrition, and result in greater session attendance. Similarly, other modularized cognitive-behavioral interventions have also reported high patient satisfaction ratings and limited attrition (Wilhelm et al., 2011; Storch et al., 2013), suggesting strong patient acceptability that may be attributed to the adaptable nature of the treatment protocol.

Although results were promising for primary outcomes, secondary clinical outcomes did not differ significantly between groups, which mirrors other pilot trials of youth with CTDs (Scahill et al., 2006b; Sukhodolsky et al., 2009). Despite these non-significant group differences, two interesting findings emerged. First, there was a clinically significant reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in the RCT (ES=0.61), which reached statistical significance in the open-label analyses (p<0.001, ES=0.86). Given that youth in the LWT condition learned to overcome tic-related avoidance and approached feared situations using step-wise exposures, youth and parents may have applied these learned skills to confront other fears. Alternatively, as many youth with CTDs have tic-related obsessive compulsive symptoms (e.g., not just right sensations, repeating rituals), it may be that youth diagnosed with OCD in the LWT group (n=4; 33%) applied competing responses (a component of HRT) to help them counter rituals, thereby resulting in habituation to obsessional worries (e.g., resisting the desire to fix re-arrange something by folding arms). Given the frequent co-occurrence of OCD with CTDs, this finding bears promise for youth with CTDs and OCD receiving LWT. Second, there was no significant difference between groups on parent-rated tic impairment in the RCT (p=0.56, ES=0.14), but a significant reduction in parent-rated tic impairment in open-label analyses (p<0.001, ES=0.91). This was somewhat surprising in light of the large effect reported by a treatment blinded evaluator. It may be that parents become accustomed to youth's impaired functioning, and accommodate accordingly. Alternatively, some aspects of tic-related impairment (e.g., loss of peer friendships, peer teasing, poor self-concept) may not be overtly distinguishable to parents as youth may keep them internalized. Thus, parents may not realize the magnitude of youth's tic-related impairment until it is reviewed in therapy. Indeed, this may account for the differential treatment effects observed between parent-rated tic impairment and child-rated quality of life observed in the RCT.

These findings should be considered within the context of study limitations. First, this study had a small sample size. Although pilot trials are intended to refine treatment approaches and problem solve pragmatic considerations (Leon et al., 2011), this study was underpowered to detect smaller between-group treatment effects. Thus, some medium-sized between-group treatment effects were not statistically significant at post-treatment (e.g., tic severity, obsessive-compulsive severity). On balance, the sample size is comparable to other pilot intervention trials among youth with CTDs (Scahill et al., 2006; Sukhodolsky et al., 2009). Second, there was a comparatively high response rate among youth in the waitlist condition (33%). This response rate was markedly higher than control conditions in larger randomized controlled trials (18.5%; Piacentini et al., 2010). Thus, some secondary characteristics that exhibited large treatment effects were still not significant between groups. However open-label analyses identified that youth receiving LWT improved significantly on secondary characteristics. Third, this trial used a waitlist control comparison. Between group treatment effects may have been smaller if a non-behavioral active comparison intervention were used instead. Fourth, this study used a one-month follow-up to examine the short-term durability of treatment gains. Given the waxing and waning nature of tics (Lin et al. 2002), it may be that a 3-or-6 month follow-up assessment used in other RCTs may yield differences in treatment durability (Piacentini et al., 2010; Woods et al., 2011). Finally, this study developed treatment modules based on an open-label pilot study conducted by (Storch et al., 2012) and clinical expertise. Future research and refinement of the LWT treatment manual may prove beneficial to identify additional modules and incorporate them into the treatment package to address problems not identified by previous parents and children with tics.

When treating youth with CTD, it is important to conduct a comprehensive evidence-based assessment to clarify treatment goals (McGuire et al., 2012). As part of this assessment, youth's quality of life should be evaluated using either general quality of life measures that have demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in youth with CTD (Storch et al., 2007b), or more CTD specific quality of life measures (Cavanna et al., 2008). While CTD specific quality of life measures have demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in Italian youth with CTD (Cavanna et al., 2013a; Cavanna et al., 2013b), such measures still require further psychometric validation in English-speaking youth with CTD prior to their widespread use. After a thorough evaluation and clarification of treatment goals, clinical guidelines should be followed for youth and families seeking reductions in tic symptom severity (Murphy et al., 2013). However, for youth also experiencing adverse psychosocial consequences related to tics and/or a poor quality of life, there exist limited empirically-supported treatment options. This pilot trial identified that the LWT intervention produced significant reductions in clinician-rated tic-impairment and improved youth’s quality of life. Thus, these youth may benefit from the LWT intervention as either a primary, augmentative, or integrative treatment with pharmacotherapy or behavior therapy. These findings encourage the evaluation of the LWT intervention in a larger and appropriately powered RCT. Future evaluations should include additional within-treatment assessments to evaluate potential mechanisms of change for tic-related impairment and quality of life (e.g., coping skills questionnaire).

Highlights.

Existing treatments focus on reducing tic severity rather than tic-related impairment

Youth with tic disorders often experience adverse psychosocial consequences due to tics

Treatment emphasized developing coping skills for psychosocial consequences of tics

Youth receiving LWT experienced reduced impairment and improved quality of life

Findings provide preliminary support for using LWT for youth with tic disorders

Acknowledgements

In alphabetical order, the authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Erin Brennan, B.A., Erika A. Crawford, B.A., Camille Hanks, B.A., Anna M. Jones, B.A., Lauren Kaercher, B.A., Morgan King, B.A., and Michael Sulkowski, Ph.D. The authors would also like to express their appreciation to the children and families who participated in this study. Support for this article comes in part from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award R01MH093381. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bawden HN, Stokes A, Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Salisbury S. Peer relationship problems in children with Tourette's disorder or diabetes mellitus. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard BA, Stebbins GT, Siegel S, Schultz TM, Hays C, Morrissey MJ, Leurgans S, Goetz CG. Determinants of quality of life in children with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2009;24:1070–1073. doi: 10.1002/mds.22487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch MH, Peterson BS, Scahill L, Otka J, Katsovich L, Zhang H, Leckman JF. Adulthood outcome of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children with Tourette syndrome. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:65–69. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudjouk PJ, Woods DW, Miltenberger RG, Long ES. Negative peer evaluation in adolescents: Effects of tic disorders and trichotillomania. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 2000;22:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, O'Donnell DA, Schultz RT, Scahill L, Leckman JF, Pauls DL. Social and emotional adjustment in children affected with Gilles de la Tourette's Syndrome: Associations with ADHD and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Luoni C, Selvini C, Blangiardo R, Eddy CM, Silvestri PR, Cali PV, Gagliardi E, Balottin U, Cardona F, Rizzo R, Termine C. Disease-specific quality of life in young patients with tourette syndrome. Pediatr Neurology. 2013a;48:111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Luoni C, Selvini C, Blangiardo R, Eddy CM, Silvestri PR, Cali PV, Seri S, Balottin U, Cardona F, Rizzo R, Termine C. The Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Quality of Life Scale for children and adolescents (C&A-GTS-QOL): development and validation of the Italian version. Behavioural Neurology. 2013b;27:95–103. doi: 10.3233/BEN-120274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Schrag A, Morley D, Orth M, Robertson MM, Joyce E, Critchley HD, Selai C. The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome-quality of life scale (GTS-QOL): development and validation. Neurology. 2008;71:1410–1416. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327890.02893.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of diagnosed Tourette Syndrome in persons aged 6–17 years – United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control. 2009;58:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman C, Murphy T, Scahill LD, Compton SN, Walkup J. Exploring the impact of chronic tic disorders on youth: Results from the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2011;42:219–242. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman CL, Murphy TK, Scahill LD, Compton SN, Walkup JT. The impact of Tourette syndrome in adults: Results from the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey. Community Mental Health Journal. 2013;49:110–120. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9465-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler D, Murphy T, Gilmour J, Heyman I. The quality of life of young people with Tourette syndrome. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2009;35:496–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M, Agodi A, Barchitta M, Cali P, Robertson MM, Rizzo R. Clinical correlates of quality of life in Tourette syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2011a;26:735–738. doi: 10.1002/mds.23434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M, Cali P, Robertson MM, Rizzo R. The effects of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on quality of life in tourette syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2012;24:458–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11080181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy CM, Rizzo R, Gulisano M, Agodi A, Barchitta M, Cali P, Robertson MM, Cavanna AE. Quality of life in young people with Tourette syndrome: a controlled study. Journal of Neurology. 2011b;258:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, Kerbeshian J, Robertson MM, Sandor P. An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42:436–447. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich S, Morgan SB, Devine C. Children's attitudes and behavioral intentions toward a peer with Tourette syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1996;21:307–319. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. National Institute for Mental Health. Rockville, MD: 1976. Clinical Global Impressions, ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology; pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, Weisz JR. Youth Versus Parent Working Alliance in Usual Clinical Care: Distinctive Associations With Retention, Satisfaction, and Treatment Outcome. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:117–128. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Freitag M, Walther M, Franklin SA, Ely L, Woods DW. A randomized pilot trial comparing videoconference versus face-to-face delivery of behavior therapy for childhood tic disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S, Walkup JT, Woods DW, Peterson A, Piacentini J, Wilhelm S, Katsovich L, McGuire JF, Dziura J, Scahill L. Detecting a clinically meaningful change in tic severity in Tourette syndrome: A comparison of three methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;36:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa N, Dalan M, Rydell AM. Tourette syndrome in the general child population: cognitive functioning and self- perception. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;64:11–18. doi: 10.3109/08039480903248096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack CW, Storch EA, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Ricketts ED, Murphy TK, Goodman WK. Quality of life in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: base rates, parent-child agreement, and clinical correlates. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:935–942. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz ER, Motlagh MG, Katsovich L, King RA, Lombroso PJ, Grantz H, Lin H, Bentley MJ, Gilbert DL, Singer HS, Coffey BJ, Kurlan RM, Leckman JF. Tourette syndrome in youth with and without obsessive compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;21:451–457. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0278-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:566–573. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Yeh CB, Peterson BS, Scahill L, Grantz H, Findley DB, Katsovich L, Otka J, Lombroso PJ, King RA, Leckman JF. Assessment of symptom exacerbations in a longitudinal study of children with Tourette's syndrome or obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1070–1077. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Mulle K. OCD in Children and Adolescents: A Cognitive-behavioral Treatment Manual. Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Hanks C, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Murphy TK. Social deficits in children with chronic tic disorders: Phenomenology, clinical correlates and quality of life. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Kugler BB, Park JM, Horng B, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Evidence-based assessment of compulsive skin picking, chronic tic disorders and trichotillomania in children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2012;43:855–883. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Brennan EA, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Small BJ, Storch EA. A meta-analysis of behavior therapy for Tourette Syndrome. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;50:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Vahl K, Dodel I, Muller N, Munchau A, Reese JP, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Dodel R, Oertel WH. Health-related quality of life in patients with Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2010;25:309–314. doi: 10.1002/mds.22900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TK, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Stock S AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with tic disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:1341–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Cohen DJ. The treatment of Tourette's syndrome: multimodal, developmental intervention. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 1):62–72. discussion 73–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Chang S, Ginsburg GS, Deckersbach T, Dziura J, Levi-Pearl S, Walkup JT. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:1929–1937. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM, Jr, Budman C, Coffey BJ, Jankovic J, Kiessling L, King RA, Kurlan R, Lang A, Mink J, Murphy T, Zinner S, Walkup J. Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome. NeuroRx. 2006a;3:192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI. Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Sukhodolsky DG, Bearss K, Findley D, Hamrin V, Carroll DH, Rains AL. Randomized Trial of Parent Management Training in Children With Tic Disorders and Disruptive Behavior. Journal of Child Neurology. 2006b;21:650–656. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210080201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Woods DW, Himle MB, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, Piacentini JC, McNaught K, Walkup JT, Mink JW. Current controversies on the role of behavior therapy in Tourette syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2013;28:1179–1183. doi: 10.1002/mds.25488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions Graywinds Publications. San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV : Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht MW, Woods DW, Piacentini J, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Chang S, Kepley H, Deckersbach T, Flessner C, Buzzella BA, McGuire JF, Levi-Pearl S, Walkup JT. Clinical characteristics of children and adolescents with a primary tic disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2011;23:15–31. doi: 10.1007/s10882-010-9223-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes A, Bawden HN, Camfield PR, Backman JE, Dooley JM. Peer problems in Tourette's disorder. Pediatrics. 1991;87:936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin AB, Nadeau JM, Jones AM, De Nadai AS, Mutch PJ, Selles RR, Ung D, Murphy TK. The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, De Nadai AS, Lewin AB, McGuire JF, Jones AM, Mutch PJ, Shytle RD, Murphy TK. Defining treatment response in pediatric tic disorders: A signal detection analysis of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2011;21:621–627. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Lack CW, Simons LE, Goodman WK, Murphy TK, Geffken GR. A measure of functional impairment in youth with Tourette's Syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007a;32:950–959. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Lack C, Milsom VA, Geffken GR, Goodman WK, Murphy TK. Quality of life in youth with Tourette's syndrome and chronic tic disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007b;36:217–227. doi: 10.1080/15374410701279545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Morgan JE, Caporino NE, Brauer L, Lewin AB, Piacentini J, Murphy TK. Psychosocial treatment improved resilience and reduce impairment in youth with tics: An intervention case series of eight youth. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2012;26:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Murphy TK, Chase RM, Keeley M, Goodman WK, Murray M, Geffken GR. Peer victimization in youth with Tourette's syndrome and chronic tic disorder: Relations with tic severity and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007c;29:211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Sajid M, Allen P, Roberti JW, Goodman WK. Reliability and validity of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:486–491. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Soto O, Sajid M, Allen P, Roberti JW, Killiany EM, Goodman WK. Psychometric evaluation of the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Zhang H, Peterson BS, King RA, Lombroso PJ, Katsovich L, Findley D, Leckman JF. Disruptive behavior in children with Tourette's syndrome: Association with ADHD comorbidity, tic severity, and functional impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:98–105. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Vitulano LA, Carroll DH, McGuire J, Leckman JF, Scahill L. Randomized trial of anger control training for adolescents with Tourette's syndrome and disruptive behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:413–421. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabori Kraft J, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, Thomsen PH, Henriksen TB, Scahill L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of tic disorders in a community sample of school-age children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;21:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM. The PedsQL as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: a population-based study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2003;3:329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman H, Qureshi IA, Leckman JF, Scahill L, Bloch MH. Systematic review: Pharmacological treatment of tic disorders – efficacy of antipsychotic and alpha-2 adrenergic agonist agents. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Piacentini J, Woods DW, Deckersbach T, Sukhodolsky DG, Chang S, Liu H, Dziura J, Walkup JT, Scahill L. Randomized trial of behavior therapy for adults with Tourette syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:795–803. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Fama JM, Greenberg JL, Steketee G. Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Piacentini J, Chang S, Deckersbach T, Ginsburg G, Peterson A, Scahill LD, Walkup JT, Wilhelm S. Managing Tourette Syndrome: A Behavioral Intervention for Children and Adults Therapist Guide: A Behavioral Intervention for Children and Adults Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Piacentini JC, Scahill L, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, Chang S, Deckersbach T, McGuire J, Specht M, Conelea CA, Rozenman M, Dzuria J, Liu H, Levi-Pearl S, Walkup JT. Behavior therapy for tics in children: acute and long-term effects on psychiatric and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Child Neurology. 2011;26:858–865. doi: 10.1177/0883073810397046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinner SH, Conelea CA, Glew GM, Woods DW, Budman CL. Peer victimization in youth with Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2012;43:124–136. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0249-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]