Abstract

Purpose

To compare age-dependent changes in health status among childhood cancer survivors and a sibling cohort.

Methods

Adult survivors of childhood cancer and siblings, all participants of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, completed three surveys assessing health status. At each of three time points, participants were classified as having poor outcomes in general health, mental health, function, or daily activities if they indicated moderate to extreme impairment. Generalized linear mixed models were used to compare survivors with siblings for each outcome as a function of age and to identify host- and treatment-related factors associated with age-dependent worsening health status.

Results

Adverse health status outcomes were more frequent among survivors than siblings, with evidence of a steeper trajectory of age-dependent change among female survivors with impairment in at least one health status domain (P = .01). In adjusted models, survivors were more likely than siblings to report poor general health (prevalence ratio [PR], 2.37; 95% CI, 2.09 to 2.68), adverse mental health (PR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.52 to 1.80), functional impairment (PR, 4.53; 95% CI, 3.91 to 5.24), activity limitations (PR, 2.38; 95% CI, 2.12 to 2.67), and an adverse health status outcome in any domain (PR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.97 to 2.23). Cancer treatment and health behaviors influence the magnitude of differences by age groups. Chronic conditions were associated with adverse health status outcomes across organ systems.

Conclusion

The prevalence of poor health status is higher among survivors than siblings, increases rapidly with age, particularly among female participants, and is related to an increasing burden of chronic health conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer during childhood predisposes patients to adverse outcomes that negatively affect health status and quality of survival.1 The risk and manifestation of adverse health outcomes in an individual patient is influenced by a myriad of factors including premorbid health conditions,2,3 genetic or familial characteristics,4–7 specific treatment modalities and intensity,8 and lifestyle issues.9 Adverse psychosocial effects of cancer on educational achievement, employment status, and household income may affect the course of late effects by their impact on survivor access to health insurance, health care, and rehabilitative services.10–12 Characterization of sociodemographic, treatment, and behavioral factors associated with increased risk of poor physical and psychological health after childhood cancer may expedite provider identification of survivors in need of access to interventions to preserve or improve health.

We previously evaluated baseline health status of adults participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS),10 which provided a cross-sectional analysis of survivorship in early adult years. However, knowledge deficits remain regarding important areas of long-term health, particularly regarding how cancer-related morbidity affects the natural course of organ senescence and its ultimate impact on long-term health status. Increasing numbers of studies have reported that survivors experience earlier onset or accelerated progression of adverse health conditions commonly associated with aging.13–15 In our current study, we assessed the CCSS cohort's health status over time, using the original six health domains to evaluate the impact of aging on cancer-related morbidity. The goal of the study was to identify sociodemographic, treatment, and behavioral factors associated with declining health status to guide clinical care and inform future investigations to improve and preserve survivor health.

METHODS

Participants

Participants for these analyses were members of the CCSS cohort who completed a series of three surveys that were distributed over a 15-year period and who consented to medical record abstraction.16,17 Briefly, eligible participants had survived cancer for at least five years and were diagnosed at one of 26 institutions in North America when they were younger than age 21 years. A sibling comparison group was also enrolled onto the study, and they completed questionnaires at similar time points. Protocol documents were approved by institutional review boards at each institution; participants provided informed consent.

Health Status

Our primary outcomes were six domains of health status: general health, mental health, functional impairment, activity limitations, pain as a result of cancer treatment, and anxiety/fears related to cancer and/or treatment. Participants contributed information corresponding to their age at the time of each survey, potentially providing responses at up to three time points. As in our previous cross-sectional analysis,10 participants were classified as having poor general health if they responded “poor” or “fair” to the question, “Would you say that your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Adverse mental health status was assigned to participants whose responses to the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 resulted in a sex-specific T-score of 63 or higher on the Global Severity Index or any one of the Depression, Anxiety, or Somatization subscales.18 Participants were categorized with functional impairment if they reported that a health problem resulted in them needing help with personal care or routine needs, or if it resulted in difficulty attending work or school. Activity limitations were assigned to participants who reported that health limited moderate activities, such as walking upstairs or climbing a few flights of stairs, or walking one block three or more months out of the past two years. Survivors were dichotomized as having medium, a lot, or very bad, excruciating pain related to their cancer/treatment versus none or a small amount of pain, and medium, a lot, or very many, extreme fears or anxiety related to their cancer/treatment versus no or a small amount of anxiety or fears. Siblings were categorized in the general and mental health categories and the functional impairment and activity limitation categories only. To characterize overall burden, the total number of adverse health status outcomes was calculated, including poor general health, adverse mental health, functional impairment, and activity limitations.

Independent Variables

We evaluated demographic variables in models, including age at questionnaire, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment (high school graduate or not), annual household income, and health insurance status. Personal characteristics included body mass index, drinking status,19 smoking status,20 and physical activity (Table 1). We considered disease and treatment variables such as primary diagnosis; age at diagnosis; time from diagnosis to questionnaire; exposure to anthracycline and alkylating agents; and radiation to the brain, chest, or abdomen. Surgical procedures included craniotomy, thoracotomy, nephrectomy, cystectomy, and amputation.

Table 1.

Host- and Treatment-Related Characteristics of Cancer Survivors and Siblings

| Characteristic | Survivor Group (n = 22,568; %)* | Sibling Group (n = 7,504; %)* | χ2 P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | < .0001 | ||

| Male | 51.9 | 46.4 | |

| Female | 48.1 | 53.6 | |

| Race/ethnicity | < .0001 | ||

| White | 88.8 | 89.2 | |

| Black | 3.7 | 2.2 | |

| Hispanic | 4.6 | 2.9 | |

| Other | 2.6 | 2.4 | |

| Not reported | 0.4 | 3.3 | |

| High school graduate | < .0001 | ||

| Yes | 87.4 | 91.5 | |

| No | 6.3 | 3.5 | |

| Not reported | 6.3 | 5.1 | |

| Annual household income | < .0001 | ||

| < $20,000 | 14.2 | 7.3 | |

| ≥ $20,000 | 74.7 | 85.6 | |

| Not reported | 11.0 | 7.0 | |

| Health insurance | < .0001 | ||

| Yes/Canadian | 86.8 | 90.0 | |

| No | 12.0 | 9.2 | |

| Not reported | 1.2 | 0.7 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2† | < .0001 | ||

| Underweight | 4.7 | 2.5 | |

| Normal | 48.0 | 46.2 | |

| Overweight | 29.1 | 30.7 | |

| Obese | 18.2 | 20.6 | |

| Heavy/binge drinker‡ | < .0001 | ||

| Yes | 10.4 | 13.3 | |

| No | 89.6 | 86.7 | |

| Smoking status | < .0001 | ||

| Never | 71.5 | 61.3 | |

| Former | 11.2 | 16.4 | |

| Current | 17.2 | 22.3 | |

| Meets CDC physical activity guidelines§ | < .0001 | ||

| Yes | 70.6 | 77.2 | |

| No | 29.4 | 22.8 | |

| Grade 3-4 chronic conditions | < .0001 | ||

| One | 25.7 | 9.8 | |

| Two or more | 10.9 | 1.7 | |

| Age group picked on questionnaire, years | < .0001 | ||

| 18-24 | 18.2 | 13.4 | |

| 25-29 | 18.7 | 17.3 | |

| 30-34 | 24.1 | 21.8 | |

| 35-39 | 19.4 | 19.9 | |

| 40-44 | 12.1 | 15.1 | |

| ≥ 45 | 7.4 | 12.6 | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||

| Mean | 9.5 | ||

| Standard deviation | 5.6 | ||

| Range | 0-20 | ||

| Time from cancer diagnosis, years | |||

| Mean | 22.4 | ||

| Standard deviation | 6.8 | ||

| Range | 6-39 | ||

| Diagnosis | |||

| Leukemia | 30.4 | ||

| CNS malignancy | 12.4 | ||

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 17.1 | ||

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 9.1 | ||

| Wilms tumor | 6.7 | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 4.1 | ||

| Soft-tissue sarcoma | 9.6 | ||

| Bone malignancy | 10.6 | ||

| Select chemotherapy exposures | |||

| Anthracycline agents | 26.9 | ||

| Alkylating agents | 52.0 | ||

| Brain radiation, maximum dose, Gy | |||

| None | 66.9 | ||

| 3.0-23.9 | 9.2 | ||

| 24.0-29.9 | 12.8 | ||

| ≥ 30.0 | 11.1 | ||

| Chest radiation, maximum dose, Gy | |||

| None | 71.6 | ||

| 6.2-23.9 | 7.4 | ||

| 24.0-37.9 | 11.4 | ||

| ≥ 38.0 | 9.6 | ||

| Abdominal radiation, maximum dose, Gy | |||

| None | 74.2 | ||

| 14.0-23.9 | 7.0 | ||

| 24.0-34.9 | 8.6 | ||

| ≥ 35.0 | 10.2 | ||

| Pelvic radiation, maximum dose, Gy | |||

| None | 79.7 | ||

| 6.1-23.9 | 5.3 | ||

| 24-34.9 | 6.7 | ||

| ≥ 35.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Surgery | |||

| Craniotomy | 10.1 | ||

| Thoracotomy | 4.4 | ||

| Nephrectomy | 5.8 | ||

| Cystectomy | 0.7 | ||

| Upper extremity amputation | 0.5 | ||

| Lower extremity amputation | 4.8 | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Represents 9,711 survivors and 3,206 siblings who completed the baseline questionnaire; 6,875 survivors and 2,351 siblings who completed the 2003 questionnaire; and 5,982 survivors and 1,947 siblings who completed the 2007 questionnaire.

BMI was categorized as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2).

Heavy/binge drinking was assigned to male participants who reported consuming > 4 drinks/day or > 14 drinks/week and to female participants who reported consuming > 3 drinks/day or > 7 drinks/week.

The equivalent of at least 150 minutes moderate physical activity per week.

We graded the severity of chronic medical conditions across 13 categories using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. Conditions were graded as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe/disabling (grade 3), or life threatening (grade 4), and were included in models if they were grade 3 or 4 and if onset was before the time of survey completion.

Statistics

Because participants contributed data from one, two, or three questionnaires, analyses were carried out with the survey as the denominator, along with covariates relevant to that survey. Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the study population. We calculated percentages of responses indicating poor health status for each outcome and compared them between siblings and survivors, overall and by diagnostic group, using generalized linear models with a log-link function to allow direct estimation of prevalence ratios (PR) along with robust variance estimates to account for within-person correlation.21 Models were adjusted for demographic and personal characteristics, except insurance status, which was not associated with outcomes in univariable analyses. To evaluate the potential difference in trajectory of change in prevalence of adverse health status between survivors and siblings as a function of age, an interaction term for survivor status by five-year age group was included in each model. Figures illustrating the age-dependent relationships were constructed using lowess smoothers.22 In separate models among survivors, we evaluated host-and treatment-related predictors of adverse health status outcomes and associations between chronic conditions and adverse health status outcomes, including variables with a univariable significance level of less than 0.1, accounting for within-person correlation with robust variance estimates. We estimated the probability of participation for each participant for each questionnaire for which they were alive, based on age at diagnosis, age at questionnaire (estimated if questionnaire was missing), sex, race, baseline educational attainment, and income. We evaluated the impact of nonparticipation by including inverse probability weights to calculate prevalence estimates and to evaluate associations between host- and treatment-related factors and each outcome. Because there were no appreciable differences between models with and without inverse probability weights, we present results from unweighted models.23 We used SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) for all analyses. Graphs were constructed with Stata version 11.2 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Participants

Of 12,846 potentially eligible study participants who were alive and age 18 years or older at the baseline survey in 1995, 9,711 participants completed the surveys. The Data Supplement (online-only) compares characteristics of participants by number of questions completed. In 2003 and 2007, respectively, 6,875 and 5,982 survivors completed surveys at each follow-up period. All three questionnaires were completed by 5,474 survivors. The comparison group included 3,206 siblings at baseline, 2,351 in 2003, and 1,947 in 2007. Characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1.

Adverse Health Status Among Siblings and Survivors by Age and Diagnosis Groups

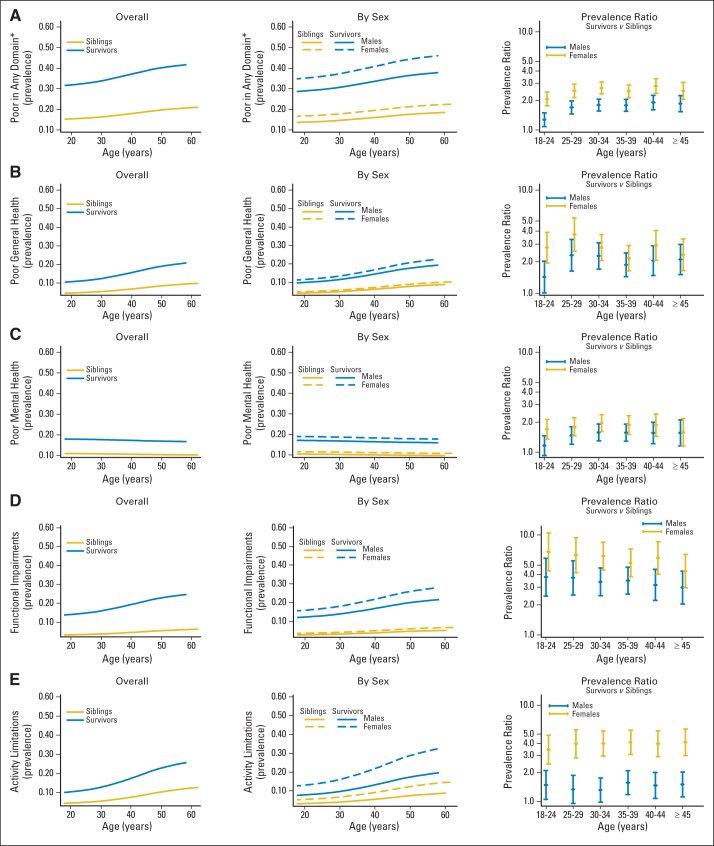

Figure 1 and the Data Supplement show overall and sex-specific percentages of survivors and siblings with adverse health status outcomes as a function of age and sex (Data Supplement; Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4) and by specific cancer histology (Data Supplement). Both survivors and siblings had an age-dependent increase in the prevalence of poor general health, functional impairment, and activity limitations. The percentages of survivors and siblings with adverse mental health status and survivors reporting cancer-related pain or anxiety did not increase with age. Adverse health status outcome percentages were higher among both male and female survivors than among siblings, with evidence of a steeper trajectory as a function of age among female survivors for poor health status in at least one domain compared with female siblings (P = .01). In adjusted models, survivors were more likely than siblings to report poor general health (PR, 2.37; 95% CI, 2.09 to 2.68), adverse mental health (PR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.52 to 1.80), functional impairment (PR, 4.53; 95% CI, 3.91 to 5.24), activity limitations (PR, 2.38; 95% CI, 2.12 to 2.67), and an adverse health status outcome in any domain (PR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.97 to 2.23; Table 3; Table 4; Data Supplement). Survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma had the largest increases in the prevalence of poor general health with age, with 10.4% increases in both groups from the 18-to-24 years old to the ≥ 45 years old age groups. HL survivors also had the greatest age-dependent increases in functional impairment and activity limitations (Table 2). By age 45 years, 25.5% of CNS tumor survivors, 23.8% of HL survivors, and 29.4% of bone-tumor survivors reported adverse health status in two or more domains when compared with 5.8% of siblings in the same age group (Data Supplement).

Fig 1.

Prevalence of survivors and siblings with a poor health status outcome in (A) any domain, (B) general health, (C) mental health, (D) function, and (E) activity by age, with prevalence ratios for each adverse outcome, comparing survivors to siblings by five-year age group.

Table 2.

Percentage of Siblings and Survivors With Adverse Health Status Outcomes by Five-Year Age Group

| Diagnosis | Poor General Health |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 Years Old |

25-29 Years Old |

30-34 Years Old |

35-39 Years Old |

40-44 Years Old |

≥ 45 Years Old |

|||||||

| % | Denominator* | % | Denominator* | % | Denominator* | % | Denominator* | % | Denominator* | % | Denominator* | |

| Siblings† | 4.8 | 968 | 4.2 | 888 | 5.2 | 1,159 | 7.0 | 1,038 | 6.6 | 754 | 8.3 | 683 |

| Survivors | 9.5 | 4,105 | 12.2 | 4,231 | 13.0 | 5,448 | 14.2 | 4,385 | 15.8 | 2,728 | 18.5 | 1,671 |

| Leukemia | 8.6 | 1,661 | 11.7 | 1,499 | 12.2 | 1,739 | 12.8 | 1,211 | 14.8 | 542 | 16.7 | 201 |

| CNS malignancy | 14.9 | 552 | 15.7 | 581 | 17.8 | 713 | 19.7 | 523 | 24.0 | 295 | 18.7 | 137 |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 11.1 | 262 | 12.0 | 466 | 12.7 | 810 | 14.3 | 890 | 17.3 | 774 | 21.5 | 667 |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 5.1 | 317 | 11.4 | 362 | 10.0 | 477 | 14.3 | 430 | 12.8 | 299 | 15.5 | 158 |

| Wilms tumor | 8.6 | 455 | 9.3 | 389 | 9.8 | 387 | 13.7 | 208 | 10.9 | 56 | 9.1 | 11 |

| Neuroblastoma | 7.9 | 319 | 12.8 | 222 | 9.7 | 239 | 13.4 | 112 | 12.5 | 24 | 0.0 | 3 |

| Soft-tissue sarcoma | 9.2 | 316 | 12.2 | 379 | 13.8 | 530 | 11.0 | 450 | 14.4 | 294 | 14.7 | 205 |

| Bone malignancy | 10.8 | 223 | 12.2 | 333 | 15.0 | 553 | 14.7 | 561 | 12.4 | 444 | 17.8 | 289 |

Evaluated in cancer survivors only.

These numbers are the denominators for the given percentages.

At the second follow-up questionnaire, only a subset of siblings were asked to complete the questions related to general health, functional impairment, and activity limitations.

Table 3.

Prevalence Ratios and 95% CIs for Adverse Health Status Outcomes by Host and Treatment-Related Factors Among Survivors

| Variable | Poor General Health |

Adverse Mental Health |

Functional Impairment |

Activity Limitations |

Cancer-Related Pain |

Cancer-Related Anxiety |

Adverse Outcome in Any Domain |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Female | 1.20 | 1.06 to 1.35 | 1.16 | 1.05 to 1.29 | 1.45 | 1.30 to 1.61 | 1.96 | 1.74 to 2.21 | 1.23 | 1.07 to 1.41 | 1.73 | 1.55 to 1.94 | 1.51 | 1.40 to 1.64 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| Nonwhite | 1.41 | 1.18 to 1.68 | 1.10 | 0.93 to 1.29 | 1.32 | 1.12 to 1.55 | 1.12 | 0.99 to 1.27 | ||||||

| Age at interview, years | ||||||||||||||

| 18-24 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| 25-29 | 1.74 | 1.44 to 2.10 | 1.62 | 1.37 to 1.91 | 1.20 | 1.00 to 1.43 | 1.19 | 0.99 to 1.44 | 1.13 | 1.02 to 1.26 | ||||

| 30-34 | 1.95 | 1.63 to 2.33 | 2.15 | 1.84 to 2.51 | 1.32 | 1.11 to 1.57 | 1.18 | 0.97 to 1.42 | 1.20 | 1.09 to 1.33 | ||||

| 35-39 | 2.29 | 1.89 to 2.77 | 2.82 | 2.38 to 3.33 | 1.89 | 1.56 to 2.29 | 1.11 | 0.90 to 1.37 | 1.27 | 1.14 to 1.42 | ||||

| 40-44 | 2.81 | 2.29 to 3.45 | 3.50 | 2.89 to 4.23 | 2.42 | 1.96 to 2.98 | 1.14 | 0.90 to 1.45 | 1.28 | 1.13 to 1.46 | ||||

| ≥ 45 | 3.52 | 2.79 to 4.43 | 4.54 | 3.63 to 5.66 | 3.57 | 2.82 to 4.51 | 0.93 | 0.69 to 1.27 | 1.63 | 1.40 to 1.90 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||||||||||||||

| 0-4 | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| 5-9 | 1.18 | 0.96 to 1.45 | 0.78 | 0.62 to 0.98 | ||||||||||

| 10-14 | 0.99 | 0.82 to 1.19 | 0.75 | 0.61 to 0.92 | ||||||||||

| 15-20 | 0.93 | 0.79 to 1.09 | 0.89 | 0.74 to 1.06 | ||||||||||

| Income < $20,000/year | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.25 | 1.98 to 2.56 | 1.84 | 1.65 to 2.05 | 2.46 | 2.18 to 2.77 | 2.14 | 1.87 to 2.44 | 2.02 | 1.75 to 2.35 | 1.51 | 1.33 to 1.72 | 1.89 | 1.72 to 2.08 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| High school graduate | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| No | 2.14 | 1.76 to 2.60 | 1.43 | 1.19 to 1.73 | 2.65 | 2.22 to 3.16 | 1.85 | 1.51 to 2.27 | 1.48 | 1.16 to 1.89 | 1.23 | 0.99 to 1.51 | 1.90 | 1.63 to 2.22 |

| Body mass index | ||||||||||||||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 1.70 | 1.35 to 2.13 | 1.12 | 0.92 to 1.38 | 1.45 | 1.17 to 1.80 | 1.65 | 1.32 to 2.07 | 1.43 | 1.11 to 1.84 | 1.44 | 1.22 to 1.69 | ||

| 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 | 1.15 | 1.01 to 1.30 | 1.08 | 0.97 to 1.20 | 1.09 | 0.98 to 1.23 | 1.10 | 0.97 to 1.25 | 1.10 | 0.95 to 1.28 | 1.08 | 0.99 to 1.17 | ||

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1.83 | 1.59 to 2.11 | 1.24 | 1.10 to 1.41 | 1.27 | 1.11 to 1.45 | 1.61 | 1.40 to 1.85 | 1.25 | 1.05 to 1.50 | 1.32 | 1.20 to 1.46 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Former | 1.50 | 1.27 to 1.77 | 1.53 | 1.33 to 1.75 | 1.46 | 1.26 to 1.69 | 1.05 | 0.89 to 1.24 | 1.62 | 1.35 to 1.94 | 1.24 | 1.06 to 1.45 | 1.35 | 1.21 to 1.51 |

| Current | 1.91 | 1.66 to 2.20 | 1.92 | 1.71 to 2.16 | 1.12 | 0.98 to 1.28 | 1.07 | 0.92 to 1.24 | 1.58 | 1.35 to 1.86 | 1.25 | 1.09 to 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.31 to 1.60 |

| Meets CDC physical activity guidelines* | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| No | 1.89 | 1.70 to 2.10 | 1.26 | 1.15 to 1.38 | 1.62 | 1.47 to 1.79 | 1.89 | 1.71 to 2.10 | 1.22 | 1.07 to 1.39 | 1.10 | 0.99 to 1.22 | 1.31 | 1.22 to 1.41 |

| Anthracyclines | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.15 | 1.00 to 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.13 to 1.51 | 1.32 | 1.12 to 1.54 | 1.14 | 1.00 to 1.29 | 1.11 | 1.01 to 1.22 | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Alkylating agents | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.26 | 1.10 to 1.44 | 1.19 | 1.08 to 1.32 | 1.21 | 1.08 to 1.35 | 1.18 | 1.03 to 1.35 | 1.18 | 1.02 to 1.37 | 1.20 | 1.06 to 1.36 | 1.16 | 1.06 to 1.27 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Cranial radiation, Gy | ||||||||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| 3.0-23.9 | 0.83 | 0.66 to 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.83 to 1.24 | 0.80 | 0.64 to 1.01 | 0.78 | 0.59 to 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.85 to 1.13 | ||||

| 24.0-29.9 | 1.02 | 0.84 to 1.24 | 1.00 | 0.83 to 1.19 | 0.72 | 0.58 to 0.89 | 1.05 | 0.84 to 1.32 | 1.05 | 0.92 to 1.19 | ||||

| ≥ 30.0 | 1.52 | 1.21 to 1.91 | 2.39 | 1.97 to 2.92 | 1.28 | 1.02 to 1.60 | 1.14 | 0.91 to 1.43 | 1.63 | 1.39 to 1.91 | ||||

| Chest radiation, Gy | ||||||||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| 6.2-23.9 | 1.33 | 1.06 to 1.65 | 0.98 | 0.81 to 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.92 to 1.56 | 1.22 | 1.05 to 1.41 | ||||||

| 24.0-37.9 | 1.35 | 1.12 to 1.62 | 0.90 | 0.76 to 1.07 | 1.36 | 1.09 to 1.69 | 1.20 | 1.05 to 1.37 | ||||||

| ≥ 38.0 | 1.27 | 1.04 to 1.55 | 1.18 | 0.99 to 1.41 | 1.55 | 1.22 to 1.95 | 1.28 | 1.12 to 1.47 | ||||||

| Abdominal radiation, Gy | ||||||||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| 1.4-23.9 | 1.02 | 0.77 to 1.36 | 0.96 | 0.75 to 1.22 | ||||||||||

| 24.0-34.9 | 0.77 | 0.60 to 0.99 | 1.11 | 0.90 to 1.37 | ||||||||||

| ≥ 35.0 | 1.03 | 0.82 to 1.29 | 1.34 | 1.12 to 1.60 | ||||||||||

| Craniotomy | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.19 | 0.94 to 1.52 | 1.23 | 1.05 to 1.44 | 1.82 | 1.48 to 2.23 | 1.47 | 1.17 to 1.86 | 1.27 | 1.08 to 1.49 | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Thoracotomy | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.32 | 1.05 to 1.67 | 1.24 | 1.04 to 1.47 | ||||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| Nephrectomy | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.84 | 0.66 to 1.07 | 0.79 | 0.61 to 1.03 | ||||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| Cystectomy | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.69 | 1.56 to 4.63 | 2.46 | 1.46 to 4.16 | 3.49 | 2.04 to 5.98 | 2.22 | 1.28 to 3.83 | 1.61 | 1.05 to 2.49 | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Lower extremity amputation | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.94 | 1.58 to 2.38 | 2.82 | 2.29 to 3.49 | 2.50 | 1.98 to 3.15 | 2.14 | 1.79 to 2.56 | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| Upper extremity amputation | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.72 | 0.85 to 3.47 | 2.85 | 1.54 to 5.30 | ||||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PR, prevalence ratio.

At least 150 minutes per week of moderate physical activity. For each outcome, all generalized estimating equations were adjusted for other host- and treatment-related risk factors with a reported PR and for within-person correlation. Variables with P < .10 were retained using backward selection criteria.

Table 4.

Prevalence Ratios and 95% CIs for Adverse Health Outcomes by Chronic Condition Status

| Variable | General Health |

Mental Health |

Functional Health |

Activity Limitation |

Cancer-Related Pain |

Cancer-Related Anxiety |

Any Adverse Health Status Domain |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| Any versus no chronic condition, grade 3-4* | 2.39 | 2.17 to 2.64 | 1.78 | 1.63 to 1.95 | 3.25 | 2.97 to 3.55 | 3.20 | 2.91 to 3.53 | 2.41 | 2.15 to 2.69 | 1.56 | 1.42 to 1.72 | 2.37 | 2.21 to 2.54 |

| One versus no chronic condition, grade 3-4* | 1.96 | 1.76 to 2.19 | 1.53 | 1.38 to 1.69 | 2.62 | 2.38 to 2.89 | 2.53 | 2.28 to 2.82 | 2.25 | 1.99 to 2.55 | 1.41 | 1.26 to 1.57 | 1.99 | 1.85 to 2.15 |

| Two or more versus no chronic conditions, grade 3-4* | 3.80 | 3.33 to 4.34 | 2.63 | 2.32 to 2.98 | 5.45 | 4.81 to 6.17 | 5.41 | 4.75 to 6.16 | 2.87 | 2.45 to 3.37 | 2.03 | 1.76 to 2.34 | 3.95 | 3.53 to 4.42 |

| Organ system-specific versus no organ-specific chronic condition, grade 3-4* | ||||||||||||||

| Second malignancy | 1.80 | 1.49 to 2.19 | 1.22 | 1.01 to 1.46 | 1.54 | 1.28 to 1.84 | 1.45 | 1.20 to 1.76 | 1.29 | 1.03 to 1.63 | 1.70 | 1.41 to 2.05 | 1.55 | 1.33 to 1.80 |

| Vision/hearing/speech | 1.69 | 1.44 to 1.98 | 1.47 | 1.26 to 1.70 | 2.56 | 2.23 to 2.95 | 1.42 | 1.21 to 1.66 | 1.35 | 1.12 to 1.64 | 1.15 | 0.97 to 1.37 | 1.77 | 1.56 to 2.01 |

| Endocrine | 1.24 | 1.05 to 1.45 | 1.41 | 1.23 to 1.62 | 1.11 | 0.96 to 1.29 | 1.17 | 1.00 to 1.37 | 1.26 | 1.05 to 1.52 | 1.24 | 1.06 to 1.46 | 1.30 | 1.16 to 1.46 |

| Respiratory | 3.10 | 2.25 to 4.28 | 2.63 | 1.83 to 3.78 | 2.42 | 1.72 to 3.41 | 3.14 | 2.19 to 4.50 | 2.57 | 1.69 to 3.91 | 2.14 | 1.44 to 3.17 | 2.46 | 1.70 to 3.56 |

| Cardiac | 2.72 | 2.30 to 3.21 | 1.72 | 1.47 to 2.03 | 2.36 | 2.00 to 2.79 | 2.89 | 2.45 to 3.41 | 1.31 | 1.06 to 1.62 | 1.23 | 1.01 to 1.50 | 2.41 | 2.07 to 2.80 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.44 | 1.13 to 1.84 | 1.29 | 1.04 to 1.61 | 1.29 | 1.03 to 1.61 | 1.41 | 1.10 to 1.81 | 1.30 | 0.98 to 1.71 | 1.48 | 1.17 to 1.87 | 1.34 | 1.13 to 1.60 |

| Renal | 1.78 | 1.16 to 2.74 | 1.55 | 1.02 to 2.35 | 1.94 | 1.21 to 3.11 | 1.77 | 1.11 to 2.83 | 1.09 | 0.61 to 1.94 | 0.98 | 0.55 to 1.75 | 1.77 | 1.15 to 2.74 |

| Musculoskeletal | 1.15 | 0.96 to 1.37 | 1.05 | 0.89 to 1.25 | 1.90 | 1.63 to 2.22 | 3.55 | 3.05 to 4.14 | 3.20 | 2.71 to 3.78 | 1.10 | 0.91 to 1.32 | 2.08 | 1.82 to 2.37 |

| Neurologic | 2.19 | 1.82 to 2.62 | 2.13 | 1.81 to 2.52 | 5.30 | 4.46 to 6.30 | 4.31 | 3.62 to 5.13 | 2.48 | 2.02 to 3.05 | 1.59 | 1.33 to 1.92 | 3.78 | 3.17 to 4.49 |

| Other hematologic† | 1.49 | 1.18 to 1.87 | 1.30 | 1.04 to 1.63 | 1.52 | 1.21 to 1.91 | 1.46 | 1.16 to 1.82 | 1.39 | 1.07 to 1.81 | 1.21 | 0.95 to 1.55 | 1.57 | 1.30 to 1.88 |

Abbreviation: PR, prevalence ratio.

Chronic conditions according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

Includes blot clots and aplastic anemia; all generalized estimating equations adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, age at questionnaire administration, age at diagnosis, body mass index, smoking status, physical activity level, and within-person correlation.

Adverse Health Status Among Survivors by Host- and Treatment-Related Factors

Table 3 lists the results of a multivariable model evaluating risk factors for poor health status outcomes in each of the six domains or any domain. Female sex, annual household income of less than $20,000 per year, not graduating from high school, obesity, smoking, and not meeting recommended physical activity guidelines were associated with adverse health status across multiple domains. Nonwhite race was associated with poor general health, adverse mental health, and functional impairment. Older age was associated with poor general health, functional impairment, and activity limitations.

Alkylating-agent exposure was associated with adverse health status across all domains. Anthracycline exposure was associated with poor general health, activity limitations, cancer-related pain, and cancer-related anxiety. Cranial radiation exposure was associated with poor general health, functional impairment, activity limitations, and cancer-related pain, with the highest risk for adverse health status in the ≥ 30 Gy dose group. Chest radiation exposure was associated with poor general health and activity limitations. A history of brain surgery was associated with poor general health, adverse mental health, functional impairment, and activity limitations. Bladder surgery was associated with poor general health, functional impairment, activity limitations, and cancer-related pain. Lower extremity amputation was associated with functional impairment and activity limitation; upper or lower extremity amputation was associated with cancer-related pain.

Adverse Health Status Among Survivors by Chronic Conditions

Table 4 details the impact of chronic health conditions on health status. In adjusted models, the risk for adverse health status across all or any domains was higher among survivors with any (versus those with none) grade 3 to 4 chronic conditions. PRs ranged from 1.56 (95% CI, 1.42 to 1.72) for cancer-related anxiety to 3.25 (95% CI, 2.97 to 3.55) for functional impairment. Survivors with two or more chronic conditions were at even greater risk, with PRs of 2.03 (95% CI, 1.76 to 2.34) for cancer-related anxiety and 5.45 (95% CI, 4.81 to 6.17) for functional impairment. Chronic conditions were associated with adverse health status across organ systems.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study indicate that childhood cancer survivors experience increasing prevalence of impairment with age in general health, functional status, and activity limitations, in excess of that reported by siblings. The presence of serious, disabling, and life-threatening chronic health conditions increases the risk of impairment across all health domains, with the greatest impact on functional impairment and activity limitations. In contrast to general health, functional, and activity domains, the prevalence of mental health impairment and moderate-to-extreme cancer-related pain or anxiety did not increase with age. This observation may be explained from our use of a distress assessment based on symptoms over the past 7 days,18 reflecting acute rather than chronic problems, or because mental health symptoms can wax and wane over time.24 Even though the proportion of adult survivors with mental health impairment seems consistent over time, we have previously observed that there are subsets of survivors whose mental health improves, while others develop new symptoms.25

Our results highlight disparities in health status outcomes related to sex, race, and age. Female sex was independently associated with an increased risk of impairment in all health status domains and a steeper rate of increase in at least one adverse health status outcome when compared with siblings. These findings may result from greater vulnerability to cancer treatment–related toxicities among women,26 or may simply reflect similar trends in the general population.27 Racial-minority participants were also more likely to have poor general health and functional impairment than were white participants. As in the general population, racial-minority childhood cancer survivors have socioeconomic indicators linked to excess risk of comorbid health conditions and reduced utilization of preventive health services, which may explain these results.28,29 Previous cross-sectional analyses of special populations in the CCSS have not disclosed elevated risk of adverse health status or differences in health care utilization among survivors with racial and ethnic minority status relative to their white counterparts.30 However, race/ethnicity and low socioeconomic status may confer unique vulnerabilities for adverse outcomes over time following childhood cancer. Further study is required to elucidate the etiology of this disparity among aging survivors and improve their access to services.

Not surprisingly, risk for poor general health, functional impairment, and activity limitations accelerated with aging in association with a higher prevalence of serious, disabling, and life-threatening chronic health conditions. These conditions have been shown to result in health-related unemployment and lost productivity among childhood cancer survivors that increase in prevalence with advancing age and time from therapy.31,32 Paradoxically, insurance restrictions and cost barriers associated with unemployment and underemployment are associated with limitations in access to rehabilitative health services.33,34 Education of survivors about new health care legislation that can be leveraged to facilitate access to medical and rehabilitative services may provide important resources to preserve health status.35

Numerous reports have documented risky health behaviors among childhood cancer survivors.20,36–48 Tobacco use, poor dietary habits, and physical inactivity may exacerbate cancer treatment–related toxicity. Some childhood cancer survivors also have abnormalities of body composition, including being overweight or obese, which increases risk of cardiovascular disease, common adult-onset cancers, and other chronic health problems.49–57 Our study quantifies the adverse impact of these modifiable risk factors on health status. Survivors who reported smoking, abnormalities of body mass index (underweight or overweight/obese), and suboptimal levels of physical activity had increased risk for poor general health as well as impairment in other health-status domains. Although smoking rates among childhood cancer survivors are generally lower than those found in noncancer populations,36,43,44 survivors seem to be less likely to quit smoking.47,58 This is particularly concerning as some survivors have greater vulnerability to tobacco-related health risks because of previous cancer treatment. Obesity, especially in combination with hypertension, increases the risk for severe, life-threatening, and fatal cardiac events in aging childhood cancer survivors.59 Moreover, the cardiovascular health risk conferred by these modifiable factors is in excess of that expected following treatment with chest radiation.59 A significant proportion of childhood cancer survivors are also underweight54 or have reduced lean muscle mass.14 These conditions are associated with increased risk of chronic health conditions and premature mortality.14,54 Unfortunately, less than one third of the survivors in the CCSS cohort follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for physical activity, which could help remediate detrimental body composition alterations.

The results of our study should be considered within the context of several methodologic limitations. As in our original study, health status was based on a composite assessment of survivor responses to validated instruments used in healthy populations and self-reported medical conditions. Although this approach enhanced the feasibility of collection of health outcomes data among a large, clinically heterogeneous pediatric cancer population, the extent of morbidity related to cancer treatment is likely underestimated owing to the high prevalence of undiagnosed disease and inconsistent surveillance in community settings.15 Survivor-specific changes in health status over the three time periods were also not assessed. Unequal participation by either more impaired or healthier survivors eligible for CCSS may result in over- or underestimation of health outcomes, although adjustment for differences known at baseline do not indicate bias. In addition, the relatively low proportion of racial and ethnic minority participants in CCSS may limit generalizability of these results to those populations. The use of a sibling control group may influence results based on sibling participation in the family cancer experience. Existing literature demonstrates that siblings report fewer mental health symptoms than the general population,60 suggesting mental health status outcomes among survivors may be underestimated when compared with population norms. Finally, health outcomes experienced by CCSS participants may not reflect those of recently treated survivors. However, an assessment of the evolution of childhood cancer therapy emphasizes that, though changes have occurred in cancer-specific treatment approaches, including surgical techniques, radiation delivery, and supportive care, there are many treatment exposures being applied to currently diagnosed patients that have been in use for more than four decades.61,62

In summary, longitudinal evaluation of adult survivors participating in the CCSS demonstrates decline in self-perceived general health in association with reduced functional status and increased activity limitations related to an increasing burden of chronic health conditions. Specific sociodemographic characteristics, cancer therapies, and health behaviors influence the magnitude of risk and help define risk profiles that can be used in counseling and clinical care of survivors (Table 5). Collectively, our findings underscore the need for systematic and ongoing assessment of health status throughout the life span of individuals treated for childhood cancer that addresses cancer-related health risks, management of chronic disease, and lifestyle factors. The complexity of health concerns among aging survivors treated with intensive multimodality therapy deserves particular attention by providers to assure optimal care coordination and maintenance of functional status. In our cohort, nearly one third of the survivors of CNS malignancy across all age groups noted functional impairment that undoubtedly contribute to the increasing prevalence of activity limitations with advancing age. Similarly, HL survivors experienced the greatest age-dependent increases in functional impairment and activity limitations. Beyond cancer diagnosis and treatment, vulnerabilities related to health disparities should be considered to facilitate survivor access to medical and rehabilitation services that restore or ameliorate early functional loss or that protect against or minimize the impact of later-onset organ-system dysfunction.63

Table 5.

Sociodemographic, Cancer Therapy, and Health Behaviors Affecting Health Status Domains

| Risk Factors by Health Status Domains | Poor General Health* | Adverse Mental Health† | Functional Impairment‡ | Activity Limitations§ | Cancer-Related Pain‖ | Cancer-Related Anxiety¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (5-6 domains) | ||||||

| Female | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Low education/income level | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Alkylating agent | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Smoker | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Low physical activity | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Obese | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Intermediate (3-4 domains) | ||||||

| Underweight | X | X | X | X | ||

| Anthracycline | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cystectomy | X | X | X | X | ||

| Age ≥ 25 years | X | X | X | |||

| Cranial radiation ≥ 30 Gy | X | X | X | |||

| Lower extremity amputation | X | X | X | |||

| Craniotomy | X | X | X | |||

| Low (1-2 domains) | ||||||

| Nonwhite race/ethnicity | X | X | ||||

| Chest radiation | X | X | ||||

| Upper extremity amputation | X | X | ||||

| Abdominal radiation > 35 Gy | X | |||||

| Thoracotomy | X |

NOTE. Clinical factors independently associated with adverse health status by multivariable analysis. Suggested patient management is as follows:

Periodic (at least annual) clinical evaluation with risk-based screenings per Children's Oncology Group guidelines; management of comorbid health conditions; counseling regarding modifying lifestyle factors.

Psychological assessment with attention to emotional health status. Referral to mental health services as indicated.

Clinical assessment of functional and activity limitations. Referral to rehabilitation services (physical and/or occupational therapy) as indicated.

Clinical assessment of chronic symptoms. Referral to pain rehabilitation services as indicated.

Psychosocial assessment with attention to access to health care and resources and ability to manage practical concerns. Referral to social work services as indicated.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Grant No. CA55727 (G.T. Armstrong, primary investigator) from the National Cancer Institute, by Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant No. CA21765 (R. Gilbertson, primary investigator) to St Jude Children's Research Hospital, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Presented at the 43rd Congress of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, Auckland, New Zealand, October 28-30, 2011.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Ann Mertens, Sharon Marie Castellino, Wendy Leisenring, Leslie L. Robison, Kirsten K. Ness

Financial support: Leslie L. Robison

Administrative support: Leslie L. Robison

Provision of study materials or patients: Leslie L. Robison

Collection and assembly of data: Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Kevin R. Krull, Ann Mertens, Wendy Leisenring, Leslie L. Robison, Kirsten K. Ness

Data analysis and interpretation: Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Kendra Jones, Tara M. Brinkman, Kevin R. Krull, Daniel A. Mulrooney, Ann Mertens, Sharon Marie Castellino, Jacqueline Casillas, James G. Gurney, Paul C. Nathan, Wendy Leisenring, Leslie L. Robison, Kirsten K. Ness

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Age-Dependent Changes in Health Status in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Cohort

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Melissa M. Hudson

No relationship to disclose

Kevin C. Oeffinger

No relationship to disclose

Kendra Jones

No relationship to disclose

Tara M. Brinkman

No relationship to disclose

Kevin R. Krull

No relationship to disclose

Daniel A. Mulrooney

No relationship to disclose

Ann Mertens

No relationship to disclose

Sharon Marie Castellino

No relationship to disclose

Jacqueline Casillas

No relationship to disclose

James G. Gurney

No relationship to disclose

Paul C. Nathan

No relationship to disclose

Wendy Leisenring

Research Funding: Merck

Leslie L. Robison

No relationship to disclose

Kirsten K. Ness

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross JA, Spector LG, Robison LL, et al. Epidemiology of leukemia in children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:8–12. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trobaugh-Lotrario AD, Smith AA, Odom LF. Vincristine neurotoxicity in the presence of hereditary neuropathy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:39–43. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malkin D, Friend SH, Li FP, et al. Germ-line mutations of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene in children and young adults with second malignant neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:734. doi: 10.1056/nejm199703063361018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Relling MV, Rubnitz JE, Rivera GK, et al. High incidence of secondary brain tumours after radiotherapy and antimetabolites. Lancet. 1999;354:34–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Relling MV, Yang W, Das S, et al. Pharmacogenetic risk factors for osteonecrosis of the hip among children with leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3930–3936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong FL, Boice JD, Jr, Abramson DH, et al. Cancer incidence after retinoblastoma. Radiation dose and sarcoma risk. JAMA. 1997;278:1262–1267. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.15.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM. Long-term complications following childhood and adolescent cancer: Foundations for providing risk-based health care for survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:208–236. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.4.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabin C. Review of health behaviors and their correlates among young adult cancer survivors. J Behav Med. 2011;34:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290:1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:61–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pui CH, Cheng C, Leung W, et al. Extended follow-up of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:640–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krull KR, Brinkman TM, Li C, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4407–4415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness KK, Krull KR, Jones KE, et al. Physiologic frailty as a sign of accelerated aging among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St Jude Lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4496–4503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derogatis LR. Scoring, and Procedure Manual. ed 4. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and Public Health: Fact Sheets—Alcohol Use and Your Health. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm.

- 20.Emmons KM, Butterfield RM, Puleo E, et al. Smoking among participants in the childhood cancer survivors cohort: The Partnership for Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:189–196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169–184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkman TM, Zhu L, Zeltzer LK, et al. Longitudinal patterns of psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1373–1381. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong GT, Sklar CA, Hudson MM, et al. Long-term health status among survivors of childhood cancer: Does sex matter? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4477–4489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women's Health: Health Factors and Risk Factors. 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/women.htm#healthstatus.

- 28.Casillas J, Castellino SM, Hudson MM, et al. Impact of insurance type on survivor-focused and general preventive health care utilization in adult survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) Cancer. 2011;117:1966–1975. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4401–4409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castellino SM, Casillas J, Hudson MM, et al. Minority adult survivors of childhood cancer: A comparison of long-term outcomes, health care utilization, and health-related behaviors from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6499–6507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dowling E, Yabroff KR, Mariotto A, et al. Burden of illness in adult survivors of childhood cancers: Findings from a population-based national sample. Cancer. 2010;116:3712–3721. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Med Care. 2010;48:1015–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirchhoff AC, Kuhlthau K, Pajolek H, et al. Employer-sponsored health insurance coverage limitations: Results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirchhoff AC, Lyles CR, Fluchel M, et al. Limitations in health care access and utilization among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5964–5972. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Zallen JP, et al. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants' perceptions and knowledge of health insurance coverage: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0225-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauld C, Toumbourou JW, Anderson V, et al. Health-risk behaviours among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:706–715. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butterfield RM, Park ER, Puleo E, et al. Multiple risk behaviors among smokers in the childhood cancer survivors study cohort. Psychooncology. 2004;13:619–629. doi: 10.1002/pon.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carswell K, Chen Y, Nair RC, et al. Smoking and binge drinking among Canadian survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers: A comparative, population-based study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:280–287. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emmons K, Li FP, Whitton J, et al. Predictors of smoking initiation and cessation among childhood cancer survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1608–1616. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Florin TA, Fryer GE, Miyoshi T, et al. Physical inactivity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1356–1363. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster MC, Kleinerman RA, Abramson DH, et al. Tobacco use in adult long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1464–1468. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frobisher C, Winter DL, Lancashire ER, et al. Extent of smoking and age at initiation of smoking among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1068–1081. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahalley LS, Robinson LA, Tyc VL, et al. Risk factors for smoking among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:428–434. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klosky JL, Howell CR, Li Z, et al. Risky health behavior among adolescents in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:634–646. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rebholz CE, Kuehni CE, Strippoli MP, et al. Alcohol consumption and binge drinking in young adult childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:256–264. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stolley MR, Restrepo J, Sharp LK. Diet and physical activity in childhood cancer survivors: A review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39:232–249. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tao ML, Guo MD, Weiss R, et al. Smoking in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:219–225. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tylavsky FA, Smith K, Surprise H, et al. Nutritional intake of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Evidence for bone health interventional opportunities. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:1362–1369. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow EJ, Pihoker C, Hunt K, et al. Obesity and hypertension among children after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2007;110:2313–2320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garmey EG, Liu Q, Sklar CA, et al. Longitudinal changes in obesity and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4639–4645. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green DM, Cox CL, Zhu L, et al. Risk factors for obesity in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:246–255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Stovall M, et al. Final height and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood brain cancer: Childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4731–4739. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inaba H, Yang J, Kaste SC, et al. Longitudinal changes in body mass and composition in survivors of childhood hematologic malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3991–3997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meacham LR, Gurney JG, Mertens AC, et al. Body mass index in long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2005;103:1730–1739. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Razzouk BI, Rose SR, Hongeng S, et al. Obesity in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1183–1189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rogers PC, Meacham LR, Oeffinger KC, et al. Obesity in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:881–891. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Withycombe JS, Post-White JE, Meza JL, et al. Weight patterns in children with higher risk ALL: A report from the Children's Oncology Group (COG) for CCG 1961. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:1249–1254. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Larcombe I, Mott M, Hunt L. Lifestyle behaviours of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1204–1209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3673–3680. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buchbinder D, Casillas J, Krull KR, et al. Psychological outcomes of siblings of cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Psychooncology. 2011;20:1259–1268. doi: 10.1002/pon.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Green DM, Kun LE, Matthay KK, et al. Relevance of historical therapeutic approaches to the contemporary treatment of pediatric solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1083–1094. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hudson MM, Neglia JP, Woods WG, et al. Lessons from the past: Opportunities to improve childhood cancer survivor care through outcomes investigations of historical therapeutic approaches for pediatric hematological malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:334–343. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stubblefield MD, Hubbard G, Cheville A, et al. Current perspectives and emerging issues on cancer rehabilitation. Cancer. 2013;119(suppl 11):2170–2178. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.