Abstract

The aim of this study was to validate the MarkWiiR (MW) captured by the Nintendo Wii-Remote (100-Hz) to assess active marker displacement by comparison with 2D video analysis. Ten participants were tested on a treadmill at different walking (1<6 km · h−1) and running (10<13 km · h−1) speeds. During the test, the active marker for MW and a passive marker for video analysis were recorded simultaneously with the two devices. The displacement of the marker on the two axes (x-y) was computed using two different programs, Kinovea 0.8.15 and CoreMeter, for the camera and MW, respectively. Pearson correlation was acceptable (x-axis r≥0.734 and y-axis r≥0.684), and Bland–Altman plots of the walking speeds showed an average error of 0.24±0.52% and 1.5±0.91% for the x- and y-axis, respectively. The difference of running speeds showed average errors of 0.67±0.33% and 1.26±0.33% for the x- and y-axes, respectively. These results demonstrate that the two measures are similar from both the x- and the y-axis perspective. In conclusion, these findings suggest that the MarkWiiR is a valid and reliable tool to assess the kinematics of an active marker during walking and running gaits.

Keywords: Assessment, Biomechanics, Bland-Altman test, Locomotion, Testing

INTRODUCTION

Kinematics is the branch of classical mechanics which describes the motion of points, bodies (objects) and systems of bodies (groups of objects) without consideration of the causes of motion [1, 2]. At the laboratory, the study of kinematics is performed with instruments such as optoelectronic devices that have the advantage of providing high accuracy in tracking markers [3]. Nevertheless, they also have the disadvantage of being expensive, with a complex configuration and procedures that require an expert technician. Moreover, they are not transportable and there are also conditions where optoelectronic devices cannot be used, for example, when there are reflective surfaces, when there is a lot of light in the environment, and when the experiment can only be performed outside the laboratory. Motion capture is an intensively used tool [4] that thanks to the technological innovation can generate video footage with high quality [5].

The disadvantage of this technique is the post-processing analysis which is time consuming and that requires a huge amount of attention to track the markers [5]. Moreover, the technology used for the recent video cameras providing high quality images comes with an increased cost. Furthermore, the data processing “frame to frame” after motion capture requires a long time for the researcher to assess kinematic analysis [6]. Besides, walking [7, 8] and running [9–11] kinematics analysis is of interest for sport scientists, in particular for those who work on gait [12] and rehabilitation [13]. Therefore, finding an easy, low-cost, time-efficient way of analyzing such motion patterns would be worthwhile.

Nintendo® has, in recent years, introduced to the market a device that is capable of tracking an active marker which emits light in the infrared spectrum [14]. The device Wii-Remote ™ (Nintendo, Kyoto -Japan) is commonly used in the field of video games. Previous research suggests the Wii-Balance-Board may also be suitable for research purposes. Indeed it has been validated for: studying jump performance [15], balance [16], rehabilitation [17], and even for surgeon training [18]. Based on the many advantages of this technology, this device can potentially be used to study kinematics by inverting the way it is used. Indeed, the Wii-Remote™ can be connected to an active marker fixed to a body part and give the possibility to study its kinematics. Hence, the aim of the present study was to validate the MarkWiiR™, comparing it with high-frequency video analysis, while studying the spatial displacement of the malleolus marker during walking and running at different speeds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Ten male students took part in the study (age 24.7±3.9 years; body mass 60.1±7.6 kg, height 1.68±0.09 m; BMI 21.1±2.0 kg·m−2). After being informed of the procedures, methods, benefits, and possible risks involved in the study, each participant reviewed and signed an informed consent form prior to participation in the study, in accordance with the ethical standards. The investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee.

Experimental setting

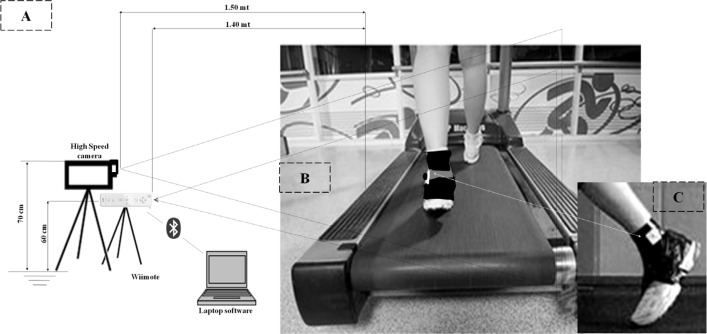

All the participants were in good general health conditions at the time of the study and they performed the test in only one session. All participants wore running shoes and performed a standardized 8-min walking warm-up at 3.5 km·h−1 [19] on a treadmill (Technogym XT Pro 600; Gambettola, Italy) at 0% slope. After the warm-up, the experiment started with the subjects walking at different speeds from 1 to 6 km·h−1 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 km·h−1) and running from 10 to 13 km·h−1 (10, 11, 12, and 13 km·h−1) on the treadmill at zero level-slope with 1 minute of passive recovery between sets [20]. The exercise periods were of 1 min each and were performed in a randomized order. Participants were asked to wear on the left malleolus an MarkWiiR™ (MW) that was captured by the Nintendo Wii-Remote™ fixed on a tripod at 0.6 m height and 1.4 m far from the sagittal plane of the participant (Figure 1). Moreover, in the flat surface the MW a reflective marker was fixed to be recorded by a camera located on a tripod placed at 0.7 m height and 1.5 m far from the sagittal plane of the subject [21].

FIG. 1.

Experimental setup. A: The position of the camera, the Wii-RemoteTM, and the laptop with respect to the treadmill. B: One subject on the treadmill. C: The infrared-LED MarkerWiiRTM and the passive marker attached to the subject's ankle.

Data collection and analysis

The reference marker displacement was detected by a High-Speed Camera (Casio FH20, Japan) with an acquisition sampling frequency of 210-Hz and resolution of 480 × 360 pixels. This resolution has a spatial precision of about 25 millimetres (Error 1.26%) for the x-axis and 19 mm (Error 0.95%) for the y-axis over a horizontal plane of 2 m. The film sequences were analyzed off-line (∼1.5 hours for each subject) using the motion analysis software Kinovea™ 0.8.15. Once the marker on the video was identified, the software automatically tracked it and extracted the displacement in two dimensions.

The new instrumentation used to record the displacement consisted of two parts: an MarkWiiR™ (Latina, Italy), and a Wii-Remote™ (Nintendo, Kyoto -Japan). The MW consisted of an infrared-LED (model Vishay TSAL 6400), fed with two batteries (CR-2032) with a total mass of about 40 g. It was tightly fixed to the left malleolus of the participants with an secured band (Vetrap™) to eliminate the MW independent swinging that allowed them to freely move for walking or running. The Wii-Remote™, also known colloquially as the Wii-mote (100 Hz), is the primary controller for Nintendo's Wii console. The Wii-Remote™ can be used as an accurate pointing device up to 5 m away from the infrared light source. The data from the MW were acquired in real time using customized CoreMeter™ based on CSharp™ software's on the Windows platform [22]. The necessary positioning calculations are based on basic trigonometry to determine the distance between the Wii-Remote and the MW emitter. The displacement of the marker on a Cartesian coordinate system corresponds to a pixel distance on the sensor. Then from the pixel distance, with inverse calculation, the real displacement was derived [18].

The signal from the camera was down-sampled from 210 Hz to 100 Hz using 1-D data interpolation. Then, the two displacement signals (x- and y-axes) from each device were synchronized with Matlab™ 8 software on the first and the last detectable peaks. Finally, the signals were normalized with respect to the maximum value of each signal because the two signals had a different order of magnitude and were incomparable. A preliminary inspection of the time-frequency characteristic (0 to 5 Hz) of the data of each subject was performed using the Fourier transformation and did not show any particular difference among signals and speeds [23].

Statistical analysis

To investigate the statistical agreement between the two devices the Pearson product moment correlation and Bland-Altman plots were used [24]. Moreover, the following variables were calculated: the bias, defined as the mean difference between MW signal [25] and the video signal; the imprecision, defined as the standard deviation of the difference between the MW signal and the video signal; the upper and lower limits of agreement, and the Z-score of the bias. The statistical agreement between the two signals was fixed to 1.96, which is the approximate value of the 97.5 percentile point of the normal distribution used in probability and statistics. Subsequently the same statistical approach was applied putting together the walking speeds and the running speeds and finally the same statistical approach was performed adding together all the speeds. Standard error of measurement (SEM) was calculated to assess the concurrent validity between the MW and the video analysis. Moreover, the effect size (Cohen's d) was computed [26] using the standard deviation of the difference between signals over the standard deviation of the video signal.

RESULTS

All the participants were able to complete the experiment and the results of the displacement of a marker on two axes (x and y) extracted from two different devices are reported in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Results of the displacement of a marker on x axis extracted from two different devices.

| Velocity (km·h−1) | Correlation | SEM | SEM (%) | ES | x axis Bias | Imprecision | LoA+ | LoA- | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.892 | 0.049 | 9.6% | 0.008 | 0.181% | 1.430% | 2.985% | −2.623% | 0.422 |

| 2 | 0.965 | 0.042 | 8.4% | 0.001 | 0.020% | 0.669% | 1.331% | −1.291% | 0.100 |

| 3 | 0.978 | 0.038 | 7.2% | 0.028 | 0.725% | 0.439% | 1.585% | −0.134% | 5.511 |

| 4 | 0.764 | 0.093 | 18.3% | 0.024 | −0.651% | 2.104% | 3.474% | −4.775% | −1.031 |

| 5 | 0.957 | 0.056 | 10.9% | 0.016 | 0.437% | 0.395% | 1.210% | −0.337% | 3.687 |

| 6 | 0.861 | 0.079 | 15.7% | 0.026 | 0.711% | 0.309% | 1.316% | 0.106% | 7.680 |

|

| |||||||||

| Walking | 0.903 | 0.060 | 11.7% | 0.009 | 0.237% | 0.518% | 1.252% | −0.778% | 0.002 |

| 10 | 0.734 | 0.108 | 20.0% | 0.034 | 0.876% | 1.383% | 3.587% | −1.836% | 2.110 |

| 11 | 0.911 | 0.075 | 14.2% | 0.037 | 0.955% | 0.344% | 1.629% | 0.281% | 9.262 |

| 12 | 0.907 | 0.076 | 14.4% | 0.009 | 0.225% | 0.403% | 1.015% | −0.565% | 1.861 |

| 13 | 0.854 | 0.091 | 17.6% | 0.025 | 0.626% | 0.635% | 1.871% | −0.619% | 3.285 |

|

| |||||||||

| Running | 0.851 | 0.088 | 16.6% | 0.027 | 0.671% | 0.328% | 1.314% | 0.027% | 0.007 |

| Locomotion | 0.882 | 0.071 | 13.6% | 0.016 | 0.411% | 0.485% | 1.361% | −0.540% | 0.003 |

Note: in the table are reported the Pearson product moment correlation (Correlation), the Standard Error of the Measure (SEM), The Percentage SEM (SEM 8%) and the Effect Size (Cohen's d) computed from the standard deviation of the difference between signals over the standard deviation of the video signal. Percentage of bias, imprecision (standard deviation of the bias), upper (LoA+) - lower (LoA-) limits of agreement, Z-score value for each speeds (1 to 13 km · h−1), mean of walking (1 to 6 km · h−1), running (10 to 13 km · h−1) and overall mean of speeds (Locomotion).

TABLE 2.

Results of the displacement of a marker on y axis extracted from two different devices.

| Velocity (km·h−1) | Correlation | SEM | SEM (%) | ES | y axis Bias | Imprecision | LoA+ | LoA- | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.875 | 0.066 | 25.5% | 0.093 | 2.208% | 0.962% | 4.094% | 0.322% | 7.650 |

| 2 | 0.946 | 0.065 | 22.6% | 0.104 | 2.689% | 1.088% | 4.821% | 0.557% | 8.240 |

| 3 | 0.945 | 0.066 | 22.1% | 0.051 | 1.394% | 0.669% | 2.704% | 0.083% | 6.948 |

| 4 | 0.684 | 0.130 | 44.7% | 0.042 | 1.175% | 1.882% | 4.863% | −2.514% | 2.080 |

| 5 | 0.945 | 0.068 | 21.6% | 0.058 | 1.599% | 1.075% | 3.705% | −0.508% | 4.958 |

| 6 | 0.857 | 0.086 | 27.3% | 0.001 | 0.062% | 2.330% | 4.628% | −4.505% | 0.088 |

|

| |||||||||

| Walking | 0.875 | 0.080 | 27.3% | 0.058 | 1.521% | 0.906% | 3.298% | −0.256% | 0.014 |

| 10 | 0.772 | 0.112 | 31.0% | 0.057 | 1.605% | 0.712% | 3.001% | 0.208% | 7.508 |

| 11 | 0.922 | 0.078 | 21.9% | 0.029 | 0.768% | 1.255% | 3.229% | −1.692% | 2.041 |

| 12 | 0.877 | 0.096 | 26.6% | 0.047 | 1.298% | 0.890% | 3.041% | −0.446% | 4.863 |

| 13 | 0.868 | 0.094 | 27.4% | 0.050 | 1.358% | 0.913% | 3.148% | −0.432% | 4.956 |

|

| |||||||||

| Running | 0.860 | 0.095 | 26.7% | 0.046 | 1.257% | 0.352% | 1.947% | 0.568% | 0.011 |

| Locomotion | 0.869 | 0.086 | 27.1% | 0.053 | 1.415% | 0.719% | 2.824% | 0.007% | 0.010 |

Note: In the table are reported the Pearson product moment correlation (Correlation), the Standard Error of the Measure (SEM), The Percentage SEM (SEM 8%) and the Effect Size (Cohen's d) computed from the standard deviation of the difference between signals over the standard deviation of the video signal. Percentage of bias, imprecision (standard deviation of the bias), upper (LoA+) - lower (LoA-) limits of agreement, Z-score value for each speeds (1 to 13 km · h−1), mean of walking (1 to 6 km · h−1), running (10 to 13 km · h−1) and overall mean of speeds (Locomotion).

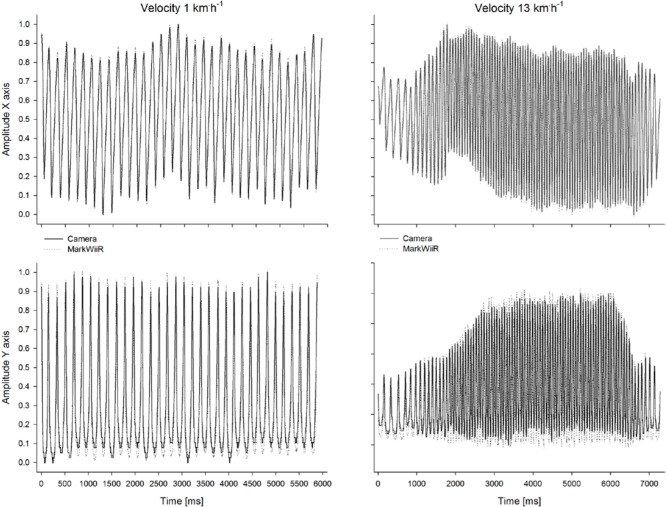

The Bland-Altman plots are provided in Figure 2. Both devices showed excellent overlapping of the marker displacement across speeds (an example is reported in Figure 3) with a modest to excellent correlation (x-axis≥0.734; y-axis≥0.684), small bias (x-axis ≤1%; y-axis ≤ 2.7%) and small imprecision (x-axis ≤ 2.1%; y-axis ≤ 2.3%). For each single speed except for 6 km·h−1 there was a difference between signals (z > 1.96) but, considering them together for the walking, running, and general locomotion (walking plus running), the z-value was less than 1.96, showing a statistical equivalence of signals. The SEM of the x-axis ranged from 0.038 (7.2%) to 0.108 (20%), and for the y-axis from 0.065 (21.6%) to 0.130 (44.7%). The ES of the x-axis ranged from 0.001 to 0.037 and for the y-axis from 0.001 to 0.104.

FIG. 2.

Bland-Altman plots of x and y dimensions of walking and running speeds. The continuous line represents the bias while the dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of agreement. For all the panels, the values of bias, imprecision, and Z-score are reported.

FIG. 3.

Example of displacement comparison from the passive markers recorded by the camera (continuous line), and displacement recorded by the MarkWiiRTM (dotted line). The displacement is reported on two dimensions x-axis and y-axes for walking at 1 km · h−1 and running at 13 km · h−1.

DISCUSSION

The present study provided a valid replacement method to the classical video analysis. The Wii-Remote™ and a new active marker “MarkWiiR™”, allow one to study the kinematics of a marker during locomotion. In this regard, the MW exhibits excellent concurrent validity with a video analysis. The criterion or construct validity [27] assessed with the correlation between the two measurements was higher than 0.7 and acceptable [23]. An overall 20% SEM gives an idea of the accuracy of the mean and the effect size of the SEM was very low (ES<0.1) [26]. These results show that the two measures are similar and could therefore be used interchangeably.

The concurrent validity, examined with Bland–Altman plots, showed a very low bias for each of the studied speeds (Figure 2). This variability was very low considering together the walking (≤ 1.521%) and running (≤ 1.257%) speeds and obviously stayed very low considering all together the studied speeds (≤ 1.415%). The excellent concurrent validity when compared with 2D video analysis suggests that it is a satisfactory device for assessing a marker displacement during locomotion (from walking to 13 km·h−1 speed running). The imprecision between the two measurements was low (< 2.3%) and the z-value of each speed, except three speeds (1 and 2 km·h−1 for the x-axis, and 6 km·h−1 for the y-axis), was up to one standard deviation; hence the two measures were different even when the bias was very small. Comparing these results with the spatial error of the video analysis (x-axis = 1.26% and y-axis = 0.96%) for the x-axis the MW error was lower while for the y-axis it was 2.8 times bigger. This disagreement between measures can be justified considering the error introduced by the spatial resolution of the video analysis. Indeed, the x bias between measures was less than 1.26%, while for the y bias it was a little higher than 0.95%. Besides, the time spent by the researcher (with expertise of 5 years) related to the data analysis of each subject was about 1.5 hours. This is time-consuming with respect to the real-time method provided by the MW, which does not require any post-exercise analysis. Therefore, the MW showed also the advantage of decreasing the data analysis process.

This kinematic measurement tool should also be validated against optotronic instruments. It should also be validated for potential use with more than one active marker. In essence, the use of this technology opens up new possibilities for research, lowering the cost of the equipment and thereby increasing the accessibility to technicians and operators. Therefore, it is suggested that the MW device fulfils the following needs: being transportable, easy to use, of low cost, and presenting a good accuracy. These characteristics warrant the promising use of such tools in the field. This provides the impetus for further research into sport and clinical applications in the clinical setting with a wide range of populations.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the results of the present study are promising. Indeed, the MW is inexpensive and it is accurate in measuring the marker displacement in locomotion. This allows a number of new applications in the field of kinematics, in rehabilitation and any field where it is required to track the displacement of a segment. The MW has the potential to ‘bridge the gap’ between laboratory testing and field testing. Many physical therapists, trainers, sports coaches and athletes require devices that can measure kinematics in 2D (i.e., walk, race-walk, run, pedalling, clean and jerk). Consequently, the MW and the custom-made software are useful to visualize the kinematics during some training activities, which could engender improvements in evidence-based training. This new methodological “real time / live” approach shortens data collection times; therefore MW is favourable compared to a simple video analysis.

Acknowledgements

Source of Funding: no external funding was received specifically for this project. No support was received from any company.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare having no conflict of interest. More specifically, there is no relationship (of any kind) between the companies named in the present article and any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor Whittaker E. A treatise on the analytical dynamics of particles and rigid bodies; Cambridge University Press; 1904. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright TW. Elements of Mechanics Including Kinematics, Kinetics and Statics; E and FN Spon; 1986. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atha J. Current techniques for measuring motion. Appl Ergon. 1984;15(4):245–257. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(84)90197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekman P, Friesen WV. A tool for the analysis of motion picture film or video tape. Am Psychol. 1969;24(3):240–243. doi: 10.1037/h0028327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharatkumar AG, Daigle K, Pandy M, Cai Q, Aggarwal J. Lower limb kinematics of human walking with the medial axis transformation; 1994. pp. 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minetti AE, Ardigò LP. The transmission efficiency of backward walking at different gradients. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442(4):542–546. doi: 10.1007/s004240100570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padulo J, Annino G, D'Ottavio S, Vernillo G, Smith L, Migliaccio GM, Tihanyi J. Footstep analysis at different slopes and speeds in elite race walking. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(1):125–129. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182541eb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padulo J, Annino G, Tihanyi J, Calcagno G, Vando S, Smith L, Vernillo G, La Torre A, D'Ottavio S. Uphill Racewalking at Iso-Efficiency Speed. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(7):1964–1973. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182752d5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padulo J, Degortes N, Migliaccio GM, Attene G, Smith L, Salernitano G, Annino G, D'Ottavio S. Footstep manipulation during uphill running. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(3):244–247. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padulo J, Annino G, Migliaccio GM, D'Ottavio S, Tihanyi J. Kinematics of running at different slopes and speeds. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(5):1331–1339. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318231aafa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padulo J, Annino G, Smith L, Migliaccio GM, Camino R, Tihanyi J, D'Ottavio S. Uphill running at iso-efficiency speed. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(10):819–823. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padulo J, Filingeri D, Chamari K, Migliaccio GM, Calcagno G, Bosco G, Annino G, Tihanyi J, Pizzolato F. Acute effects of whole-body vibration on running gait in marathon runners. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(12):1120–1126. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.889840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kesar TM, Sauer MJ, Binder-Macleod SA, Reisman DS. Motor learning during poststroke gait rehabilitation: a case study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2014;38(3):183–189. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark RA, Paterson K, Ritchie C, Blundell S, Bryant AL. Design and validation of a portable, inexpensive and multi-beam timing light system using the Nintendo Wii hand controllers. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(2):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto K, Matsuzawa M. Validity of a jump training apparatus using Wii Balance Board. Gait Posture. 2013;38(1):132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark RA, Bryant AL, Pua Y, McCrory P, Bennell K, Hunt M. Validity and reliability of the Nintendo Wii Balance Board for assessment of standing balance. Gait Posture. 2010;31(3):307–310. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsch JE, Brettler A, Smith C, Welsh J, John R, Guarrera-Bowlby P, Kafri M. Nintendo wii sports and wii fit game analysis, validation, and application to stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(6):701–719. doi: 10.1310/tsr1806-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiimote 3D. Interaction in VR Assisted Assembly Simulation. http://www.nadakthse/utbildning/grukth/exjobb/rapportlistor/2011/rapporter11/ringman_olsson_mikael_11072pdf 2014.

- 19.Wass E, Taylor NF, Matsas A. Familiarisation to treadmill walking in unimpaired older people. Gait Posture. 2005;21(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padulo J, Chamari K, Ardigò LP. Walking and running on treadmill: the standard criteria for kinematics studies. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(2):159–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belli A, Rey S, Bonnefoy R, Lacour JR. A Simple Device for Kinematic Measurements of Human Movement. Ergonomics. 1992;35(2):177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vando S, Unim B, Cassarino SA, Padulo J, Masala D. Effectiveness of perceptual training proprioceptive feedback in a virtual visual diverse group of healthy subjects: a pilot study. Italian J Public Health. 2013;10:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Impellizzeri FM, Marcora SM. Test validation in sport physiology: lessons learned from clinimetrics. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2009;4(2):269–277. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.4.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padulo J, Maffulli N, Ardigò LP. Signal or noise, a statistical perspective. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(13):E1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400112111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(9):917–928. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]