Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate test reliability of the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 (YYIR1) in 36 high-level youth soccer players, aged between 13 and 18 years. Players were divided into three age groups (U15, U17 and U19) and completed three YYIR1 in three consecutive weeks. Pairwise comparisons were used to investigate test reliability (for distances and heart rate responses) using technical error (TE), coefficient of variation (CV), intra-class correlation (ICC) and limits of agreement (LOA) with Bland-Altman plots. The mean YYIR1 distances for the U15, U17 and U19 groups were 2024 ± 470 m, 2404 ± 347 m and 2547 ± 337 m, respectively. The results revealed that the TEs varied between 74 and 172 m, CVs between 3.0 and 7.5%, and ICCs between 0.87 and 0.95 across all age groups for the YYIR1 distance. For heart rate responses, the TEs varied between 1 and 6 bpm, CVs between 0.7 and 4.8%, and ICCs between 0.73 and 0.97. The small ratio LOA revealed that any two YYIR1 performances in one week will not differ by more than 9 to 28% due to measurement error. In summary, the YYIR1 performance and the physiological responses have proven to be highly reliable in a sample of Belgian high-level youth soccer players, aged between 13 and 18 years. The demonstrated high level of intermittent endurance capacity in all age groups may be used for comparison of other prospective young soccer players.

Keywords: football, talent identification, talent selection, aerobic capacity, reliability

INTRODUCTION

The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 (YYIR1) has been extensively studied in different populations and age groups [1]. Also, the YYIR1 has been described as a valid tool in adult professional [2] and non-elite youth soccer players [3], in soccer referees [4] and in youth handball players [5]. In intermittent sports, such as soccer, where high-intensity activities are interspersed with periods of (active) recovery, the YYIR1 may assist as a valuable tool to measure an athlete’s intermittent endurance capacity. Moreover, in recent literature, the YYIR1 has often been used in talent identification and development programmes in youth soccer populations [6–8].

Measures of reliability are extremely important in sports sciences [9]. A coach needs to know whether an improvement (in intermittent endurance) is real or due to a large amount of measurement error. For example, Krustrup et al. [2] reported the good test-retest reliability of the YYIR1 (coefficient of variation (CV) of 4.9%) in 13 adult professional soccer players, whilst Thomas et al. [10] found a CV of 8.7% in 18 recreationally active adults. Also, Castagna et. al [11] reported a CV of 3.8% for the YYIR1 in 18 elite youth soccer players (14.4 years) of San Marino. However, the latter study aimed to investigate the direct validity between endurance field tests and match performance, rather than the reliability of the YYIR1.

Recently, a test-retest reliability study by Deprez et al. [3] reported CVs of 17.3, 16.7 and 7.9% in U13 (n = 35), U15 (n = 32) and U17 (n = 11) non-elite youth soccer players, respectively, showing adequate to high reproducibility of the YYIR1. This study was the first to investigate the reliability of the YYIR1 in a large sample of youth soccer players, aged between 12 and 16 years. However, the authors mentioned possible concerns in interpreting the results regarding the protocol used (2 test sessions), the level of the players (sub- and non-elite), and the relatively high coefficients of variation, typical errors and limits of agreement compared with those reported in adults. Therefore, as a consequence of previous findings and similar to the previous study, we conducted a reliability study with three test sessions in high-level youth soccer players, aged between 13 and 18 years. Also, since structured talent identification (and development) programmes are now fundamental at the highest (youth) level for the preparation of future (professional) athletes, information about the reliability of evaluation tools is essential. Consequently, the aim of the study was to investigate test reliability of the YYIR1 performance and physiological responses in high-level youth soccer players.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and design

Participants were 76 youth soccer players from one professional Belgian soccer club, aged between 13.1 and 18.5 years, who underwent a high-level soccer training programme (6 training hours and 1 game (on Saturday) per week). All players were assessed for anthropometrical characteristics and three YYIR1 in November 2013. Players were divided into three age groups according to their birth year (U15, U17 and U19) For example, players born in 1999 and 2000 were assigned to the U15 age group. All participants and their parents or legal representatives were fully informed about the aims of the study and written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital (approval number: EC 2009/572), and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration.

Only all youth players who completed three YYIR1 in three consecutive weeks were retained in the analyses (n = 36), against which a total of 40 players were excluded (drop-out rate of 53%). As a consequence, 22 players, 10 players and 4 players were retained in age groups U15 (13.9 ± 0.5 years; 162.3 ± 10.3 cm; 47.7 ± 10.1 kg), U17 (16.2 ± 0.6 years; 173.9 ± 4.9 cm; 61.8 ± 8.4 kg) and U19 (18.1 ± 0.4 years; 176.4 ± 7.1 cm; 67.4 ± 5.5 kg), respectively.

The YYIR1 was conducted according to the guidelines described by Krustrup and colleagues [2], each time on Tuesday (November 2013), and started around 6 pm (successively U15 > U17 > U19). All players were familiarized with the YYIR1 (players were part of the Ghent Youth Soccer Project follow-up study [12] and ran at least two YYIR1 before the start of the present study) and were asked to refrain from strenuous training exercise 48 h before each test session. All tests were conducted on the same outdoor location (artificial turf) in dry, windless weather conditions (temperature about 10°C in each test assessment), wearing soccer boots. Participants were given feedback on their performances after completing all three test sessions.

Heart rate (HR) was recorded every second during each test session with a heart rate monitoring system (Polar Team2 System, Kempele, Finland). The start HR (HR at first beep), the submaximal HR (after level 14.8, circa 90% of maximal HR), the peak HR (highest heart rate recorded), and the recovery HRs after 30 seconds, and 1 and 2 minutes after completing the test were used for analyses. It was found that the heart rates at fixed points during the YYIR1 test (i.e., after 6 and 9 min) were inversely correlated with the YYIR1 performance [2]. However, this relationship was not established after 3 min, suggesting that the test should be longer than 3 minutes. Therefore, the submaximal heart rate after completing level 14 (i.e., after 14.8) was included in the present analyses. This submaximal version corresponds to a total time of exactly 6 minutes and 22 seconds. All heart rates, except for the peak HR (bpm), were expressed as percentage of peak HR.

Statistics

All analyses were performed separately for the three age groups. First, the differences between test sessions were checked for outliers and 3 players were excluded from the analyses (differences were larger than 2 SDs). Test reliability was carried out using pairwise comparisons between the 3 test sessions. Absolute reliability was measured using the typical error (TE = SDdiff / √2) and coefficient of variation (CV = (TE / grand mean) * 100), and relative reliability was investigated using intra-class correlations (ICC), and considered as excellent between 0.75 and 1.00, good between 0.41 and 0.74, and poor between 0.00 and 0.40 [13]. All reliability calculations (TE, CV and ICC) were accompanied with 90% confidence intervals (CI).

In addition, the ratio limits of agreement (LOA) (log transformed data) with Bland and Altman plots were examined to illustrate the differences in YYIR1 performances between test sessions for all age groups together [9], [14]. SPSS for Windows (version 20.0) was used for all calculations. All data are presented as mean (SD) values.

RESULTS

The grand mean YYIR1 performances for the U15, U17 and U19 age groups were 2024 ± 470 m, 2404 ± 347 m, and 2475 ± 347 m, respectively (Table 1). The ICCs for these age groups were considered excellent and varied between 0.87 and 0.95. The TEs (and accompanying CVs) for the YYIR1 differences between test sessions 1 and 2 were 137 m (6.8%), 101 m (4.3%) and 107 m (4.1%); between test sessions 2 and 3 were 149 m (7.1%), 77 m (3.1%) and 74 m (3.0%); and between test sessions 1 and 3 were 147 m (7.5%), 126 m (5.4%) and 172 m (6.9%), for age groups U15, U17 and U19, respectively. The ICCs amongst test sessions for all HRs were considered excellent and varied between 0.76 and 0.97, except for the recovery HR after 1 minute, which was considered as good (ICC = 0.73). Table 1 gives a detailed overview of mean (SD) values for each test session and pairwise comparisons with TEs and CVs.

TABLE 1.

Means (SD) for YYIR1 distance and heart rates for each test moment with pairwise typical errors (TE (90% confidence interval)) and coefficients of variation (CV (90% confidence interval), and grand mean intra-class correlation (ICC (90% confidence interval)) between the three test moments.

| Variable | Age category | n | Weekl mean (SD) | Week 2 mean (SD) | Week 3 mean (SD) | Grand Mean mean (SD) | TE (abs) 1-2 (90% CI) | CV (%) 1 -2 (90% CI) | TE (abs) 2-3 (90% CI) | CV (%) 2-3 (90% CI) | TE (abs) 1 -3 (90% CI) | CV (%) 1-3 (90% CI) | ICC (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YYIR1 (m) | U15 | 22 | 1849 (471) | 2162 (523) | 2062 (409) | 2024 (470) | 137 (110-184) | 6.8 (5.5-9.2) | 149 (119-200) | 7.1 (5.6-9.5) | 147 (118-198) | 7.5 (6.0-10.1) | 0.92 (0.85-0.96) |

| U17 | 10 | 2288 (357) | 2496 (322) | 2428 (360) | 2404 (347) | 101 (74-167) | 4.3 (3.1-7.0) | 77 (56-126) | 3.1 (2.3-4.8) | 126 (92-207) | 5.4 (3.9-8.8) | 0.95 (0.87-0.98) | |

| U19 | 4 | 2610 (266) | 2660 (314) | 2370 (415) | 2547 (337) | 107 (66-312) | 4.1 (2.5-11.8) | 74 (46-217) | 3.0 (1.8-8.6) | 172 (106-500) | 6.9 (4.3-20.1) | 0.87 (0.41-0.99) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| HR start (%) | U15 | 22 | 53.5 (4.4) | 53.8 (4.4) | 53.7 (4.1) | 53.7 (4.2) | 2.2 (1.8-3.0) | 2.1 (1.7-2.9) | 2.1 (1.7-2.8) | 2.0 (1.6-2.7) | 1.6 (1.3-2.1) | 3.0 (2.4-3.9) | 0.95 (0.90-0.97) |

| U17 | 10 | 49.3 (4.5) | 47.9 (4.7) | 48.4 (4.9) | 48.5 (4.6) | 2.2 (1.6-3.6) | 2.2 (1.6-3.6) | 1.8 (1.3-3.0) | 2.2 (1.6-3.6) | 0.8 (0.6-1.4) | 1.6 (1.2-2.9) | 0.97 (0.91-0.99) | |

| U19 | 4 | 45.4 (9.5) | 47.0 (10.6) | 45.7 (11.0) | 46.0 (10.3) | 3.2 (2.0-9.3) | 3.2 (2.0-9.6) | 2.6 (21.6-7.6) | 2.9 (1.8-8.7) | 2.2 (1.4-6.4) | 4.8 (3.1-14.1) | 0.97 (0.82-1.00) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| HR submax (%) | U15 | 22 | 95.4 (2.4) | 95.3 (2.1) | 95.1 (1.7) | 95.3 (1.8) | 2.5 (2.0-3.3) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 2.1 (1.7-2.9) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) | 1.1 (0.9-1.6) | 0.92 (0.86-0.96) |

| U17 | 10 | 92.8 (3.0) | 91.8 (1.5) | 92.1 (1.9) | 92.3 (1.9) | 2.7 (2.0-4.5) | 1.5 (1.1-2.5) | 1.4(1.0-2.3) | 1.5 (1.1-2.5) | 1.7 (1.2-2.8) | 1.8 (1.3-3.0) | 0.95 (0.87-0.98) | |

| U19 | 4 | 88.1 (2.7) | 89.5 (4.3) | 90.0 (4.3) | 89.2 (3.7) | 2.0 (1.2-5.8) | 1.1 (0.7-3.3) | 2.9 (1.8-8.3) | 1.5 (1.0-4.6) | 1.2 (0.7-3.4) | 1.3 (0.8-3.8) | 0.95 (0.72-1.00) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Peak HR (b.min-1) | U15 | 22 | 202 (6) | 200 (6) | 201 (6) | 201 (6) | 2.2 (1.7-2.9) | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) | 0.8 (0.7-1.1) | 2.5 (2.0-3.3) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 0.90 (0.82-0.95) |

| U17 | 10 | 199 (6) | 198 (6) | 198 (7) | 198 (6) | 1.7 (1.2-2.8) | 0.8 (0.6-1.4) | 1.7 (1.2-2.8) | 0.8 (0.6-1.4) | 2.3 (1.7-3.8) | 1.5 (0.9-1.9) | 0.94 (0.86-0.98) | |

| U19 | 4 | 202 (11) | 198 (9) | 198 (8) | 199 (9) | 2.9 (1.8-8.3) | 1.4 (0.9-4.1) | 1.5 (0.9-4.3) | 0.7 (0.5-2.2) | 3.2 (2.0-9.3) | 1.6 (1.0-4.7) | 0.93 (0.62-1.00) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| HR rec 30" (%) | U15 | 22 | 93.0 (2.9) | 93.1 (2.3) | 93.1 (2.3) | 93.1 (2.2) | 3.4 (2.7-4.5) | 1.8 (1.5-2.5) | 2.4 (1.9-3.2) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 1.6 (1.3-2.2) | 1.7 (1.4-2.4) | 0.76 (0.60-0.87) |

| U17 | 10 | 94.1 (2.3) | 93.6 (1.7) | 94.4 (1.2) | 94.0 (1.4) | 4.0 (2.9-6.6) | 2.1 (1.6-3.5) | 2.8 (2.1-4.6) | 2.1 (1.6-3.5) | 1.3 (0.9-2.1) | 1.4 (1.0-2.2) | 0.80 (0.56-0.93) | |

| U19 | 4 | 94.2 (1.2) | 94.3 (1.5) | 93.7 (1.4) | 94.1 (1.1) | 3.2 (2.0-9.4) | 1.8 (1.1-5.3) | 3.0 (1.8-8.7) | 1.7 (1.0-5.0) | 1.0 (0.6-2.9) | 1.1 (0.6-3.1) | 0.92 (0.58-0.99) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| HR rec 1’ (%) | U15 | 22 | 81.6 (5.2) | 81.8 (4.7) | 82.6 (4.3) | 82.0 (4.2) | 5.2 (4.4-7.3) | 3.6 (2.9-4.9) | 5.3 (4.2-7.1) | 3.4 (2.7-4.6) | 3.1 (2.5-4.2) | 3.8 (3.0-5.1) | 0.73 (0.56-0.85) |

| U17 | 10 | 81.9 (6.6) | 80.5 (4.9) | 81.4 (5.1) | 81.2 (5.3) | 4.7 (3.4-7.7) | 2.7 (2.0-4.5) | 4.9 (3.6-8.1) | 2.7 (2.0-4.5) | 2.4 (1.8-3.9) | 2.9 (2.2-4.8) | 0.91 (0.79-0.97) | |

| U19 | 4 | 84.0 (1.7) | 83.8 (2.2) | 80.7 (1.4) | 82.8 (0.5) | 5.3 (3.3-15.4) | 3.3 (2.0-10.0) | 3.4 (2.4-11.3) | 2.3 (1.4-6.9) | 1.9 (1.2-5.7) | 2.3 (1.5-6.9) | 0.81 (0.26-0.99) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| HR rec 2’ (%) | U15 | 22 | 69.4 (5.6) | 69.1 (5.9) | 70.6 (4.8) | 69.7 (5.1) | 3.0 (2.4-4.0) | 2.3 (1.9-3.1) | 4.8 (3.9-6.5) | 3.6 (2.9-4.9) | 2.9 (2.4-4.0) | 4.1 (3.4-5.7) | 0.89 (0.80-0.94) |

| U17 | 10 | 67.5 (7.0) | 66.0 (7.4) | 66.6 (7.0) | 66.7 (6.9) | 3.8 (2.7-6.2) | 2.9 (2.1-4.8) | 5.8 (4.3-10.0) | 2.9 (2.1-4.8) | 2.5 (1.8-4.0) | 3.7 (2.7-5.8) | 0.93 (0.83-0.98) | |

| U19 | 4 | 70.5 (6.0) | 71.2 (5.8) | 68.1 (3.3) | 69.9 (4.9) | 3.3 (2.1-9.7) | 2.5 (1.6-7.6) | 4.9 (3.0-14.2) | 3.1 (1.9-9.2) | 2.2 (1.4-6.4) | 3.2 (2.0-9.2) | 0.91 (0.55-0.99) | |

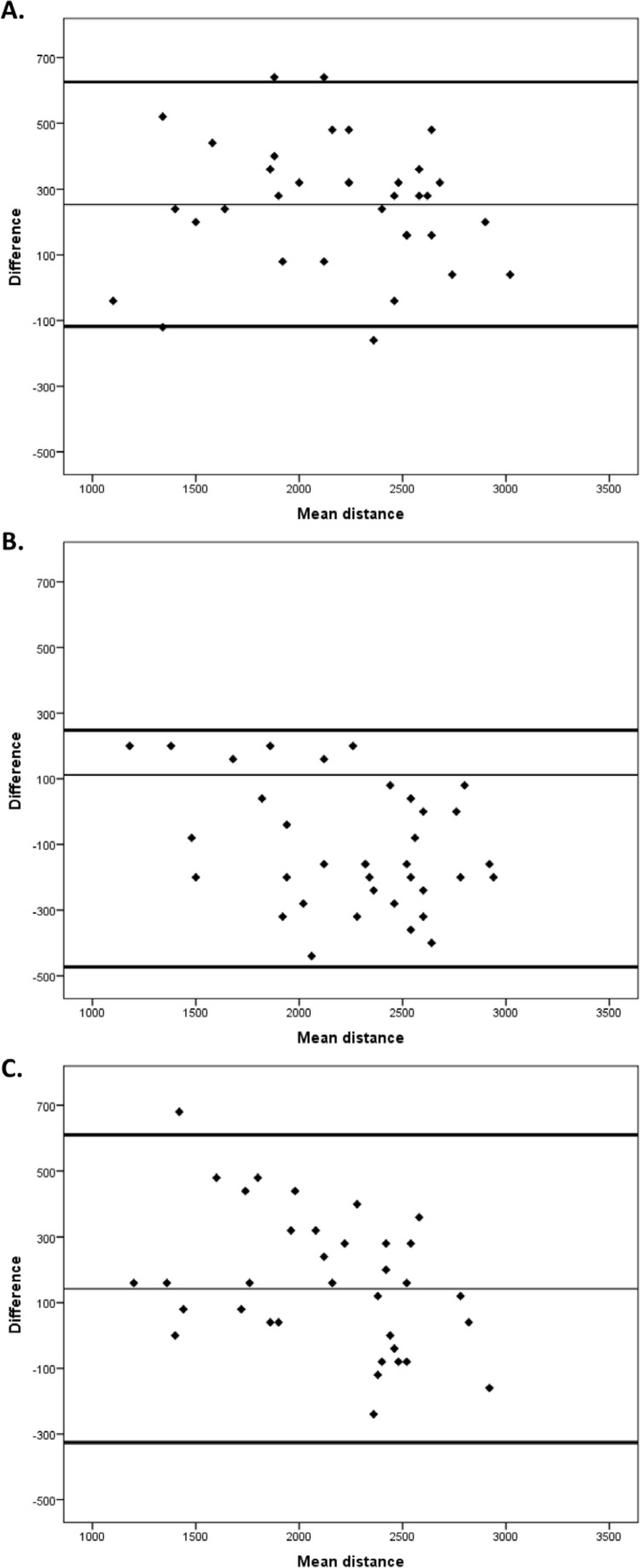

The 95% ratio LOA between test sessions 1 and 2 were 1.17 */÷ 1.24, 1.09 */÷ 1.13 and 1.02 */÷ 1.11, for age groups U15, U17 and U19, respectively (Table 2). Similar analyses between test session 2 and 3 revealed 95% LOA of 0.96 */÷ 1.23, 0.97 */÷ 1.09 and 0.88 */÷ 1.12, for age groups U15, U17 and U19, respectively. Finally, the 95% LOA between test sessions 1 and 3 were 1.13 */÷ 1.28, 1.06 */÷ 1.15, and 0.90 */÷ 1.22 for age groups U15, U17 and U19, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates Bland and Altman plots for the differences between test sessions 1 and 2, test sessions 2 and 3, and test sessions 1 and 3 for all players.

TABLE 2.

Sample size, measurement means and differences (log transformed), the ratio limits of agreement with the limit range, and correlations between the absolute differences (Abs diff.) and the mean.

| Log transformed YYIR1 measurements | Ratio limits | Range | Correlation (Abs. diff. v mean) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| n | Week 1 | Week 2 | Difference (SD) | ||||

| U15 | 22 | 7.489 | 7.647 | 0.157 (0.111) | 1.17 */÷ 1.24 | 0.94 to 1.45 | 0.98 |

| U17 | 10 | 7.724 | 7.815 | 0.091 (0.063) | 1.09 */÷ 1.13 | 0.96 to 1.23 | 0.98 |

| U19 | 4 | 7.863 | 7.881 | 0.017 (0.053) | 1.02 */÷ 1.11 | 0.92 to 1.13 | 0.97 |

|

| |||||||

| n | Week 1 | Week 2 | Difference (SD) | Ratio limits | Range | Correlation (Abs. diff. v mean) | |

|

| |||||||

| U15 | 22 | 7.647 | 7.611 | −0.036 (0.104) | 0.96 */÷ 1.23 | 0.78 to 1.18 | 0.31 |

| U17 | 10 | 7.815 | 7.784 | −0.030 (0.045) | 0.97 */÷ 1.09 | 0.89 to 1.06 | −0.29 |

| U19 | 4 | 7.881 | 7.759 | −0.122 (0.056) | 0.88 */÷ 1.12 | 0.79 to 0.99 | −0.96 |

|

| |||||||

| n | Week 1 | Week 2 | Difference (SD) | Ratio limits | Range | Correlation (Abs. diff. v mean) | |

|

| |||||||

| U15 | 22 | 7.489 | 7.611 | 0.121 (0.125) | 1.13 */÷ 1.28 | 0.88 to 1.45 | −0.22 |

| U17 | 10 | 7.724 | 7.784 | 0.070 (0.072) | 1.06 */÷ 1.15 | 0.92 to 1.22 | 0.03 |

| U19 | 4 | 7.863 | 7.759 | −0.104 (0.103) | 0.90 */÷ 1.22 | 0.74 to 1.10 | −0.64 |

FIG. 1.

Bland and Altman plots with 95% LOA for the total sample (n = 36) between (A) test sessions 1 and 2, (B) test sessions 2 and 3, and (C) test sessions 1 and 3.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the test reliability of the YYIR1 performance in 36 Belgian high-level youth soccer players, aged between 13 and 18 years. Therefore, three test sessions in three consecutive weeks were conducted. Overall, it emerged from the results that the YYIR1 is highly reproducible with CVs between 3.0 and 7.5% over all age groups. Also, excellent relative reliability was found within each age group for YYIR1 performance (ICCs between 0.87 and 0.95). Additionally, the physiological responses have also been found to be highly reliable. The present results encourage the use of the YYIR1 to assess and evaluate the intermittent endurance capacity in high-level youth soccer players. Also, age-specific reference values of the present soccer sample may be useful to trainers and coaches in the development and evaluation processes.

The YYIR1 performances of the present high-level youth soccer population demonstrated the high level of intermittent endurance capacity when compared with elite youth soccer players of San Marino, Croatia and Belgium, who performed between 400 and 2219 m from U15 to U19 age groups [6–8]. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that the present youth soccer sample is subjected to training stimuli which greatly focus on the development of the intermittent endurance capacity, therefore explaining the high level of YYIR1 performances. Consequently, the present data could serve as reference values or standards for a youth soccer sample in a high-level soccer development programme. However, we do acknowledge that the small number of U19 players is a limitation of the present study. Sample size calculations for a minimal detectable change of 94 m (0.2 times the between-subject standard deviation) with similar typical errors between 74 and 172 m revealed a minimum of 10 and 37 players, respectively [15]. Additionally, data concerning biological maturation (predicted years from peak height velocity via Mirwald et al. [16]) were deliberately excluded, although available, for the reasons that (1) the YYIR1 performance is relatively little influenced by the maturational status of the player [8], and (2) the YYIR1 performances according to the players’ biological maturation were not the focus of the present study. Moreover, the use of the maturity offset protocol is only justifiable in the U15 and U17 age groups and not in the U19 age group, as the age range within which the equation can be used confidently is 9.8 to 16.8 years [16].

The present results demonstrated the high degree of reproducibility of the YYIR1 distance (ICCs between 0.87 and 0.95; CVs between 3.0 and 7.5%) in youth soccer players, aged between 13 and 18 years. Studies investigating the YYIR1 test-retest reliability revealed CVs of 4.9% and 8.7% in 13 adult professional soccer players and 18 recreationally active adults, respectively [2], [10]. However, as today the YYIR1 is well established in talent identification and development programmes [6], [7], [8], little information about the YYIR1 reliability is known in young high-level soccer players. However, Deprez et al. [3] reported in non-elite youth soccer players CVs of 17.3%, 16.7% and 7.9% in age groups U13, U15 and U17, respectively, which suggests that the YYIR1 test is more reliable in a high-level youth soccer population.

The small ratio LOA revealed that any two YYIR1 performances in one week will not differ by more than 9 to 28% due to measurement error across all age groups. The highest agreement was found between test 2 and 3 for the U17 age group (small bias: 0.97, and excellent agreement ratio: 1.09). The worst agreements were found between test sessions 1 and 2, and between test sessions 1 and 3 for the U15 age group (biases: 1.17 and 1.13, and agreement ratios: 1.24 and 1.28) which could indicate that the youngest players had the least experience with the YYIR1 or benefit/improve the most from the physical overload in the first test session during the last two sessions. Moreover, the bias between test moment 2 and 3 for the U15 age group was significantly lower (0.96) but with a similar agreement ratio (1.23), accounting for the larger variation in YYIR1 performance (reflected by larger standard deviations) and shorter distances run in comparison with the older age groups. Also, the typical errors in the U15 age group (137 to 149 m, which corresponds with approximately 3.5 running bouts) were remarkably higher than those in the U17 (77 to 126 m) and U19 age group (74 to 107 m, except for the TE between test sessions 1 and 3: 172 m) which corresponds to approximately 2 to 2.5 running bouts. It seems possible that the grand mean YYIR1 performance of 2024 m (± level 18.8) for a typical U15 player could decrease to 1884 m (± level 18.4) or improve to 2164 m (± level 19.3) within one week. This largest performance range in the present study is likely to be of great practical application for coaches on the field and seems acceptable by sport scientists involved in exercise or performance testing.

The HRs during the YYIR1 progressively increased and reached mean peak HRs of 201, 198 and 198 bpm for the U15, U17 and U19 age groups, respectively, which corresponds to the athlete’s maximal HR on the condition that players were motivated to perform maximally [2]. Also, the submaximal HRs, expressed as percentage of peak HR, varied between 89.2 and 95.3%, and were inversely correlated with the mean YYIR1 distance (r = -0.64, -0.63 and -0.53 for the U15, U17 and U19 age groups, respectively). Together with the observations of Krustrup et al. [2] that the submaximal HRs during the season were lower than those measured during the preseason, it seems that the YYIR1 is appropriate to measure changes in physical fitness without using the test to maximal exhaustion. Further, players’ recovery HRs were very similar between all age groups and were approximately 94, 81 and 69% of peak HR, 30 seconds, 1 and 2 minutes after the end of the test, respectively. The present recovery HRs are slightly higher than those reported by Krustrup and colleagues [2], who found recovery HRs after 1 and 2 minutes of 79.1 and 64.7%, respectively. This improved recovery in professional adult soccer players could be attributed to higher and more soccer-specific training loads, leading to a better soccer-specific intermittent endurance capacity, resulting in a higher capacity to recover after intensive efforts [17].

Additionally, small absolute TEs (between 1.4 and 5.8 bpm) and CVs (between 0.7 and 4.8%) with high ICCs (between 0.73 and 0.97) for all physiological responses were observed between test moments, resulting in the high reproducibility of HR measurements during the YYIR1 test. This finding might encourage coaches to survey the players’ HRs with the aim of monitoring improvements or decrements in physical fitness during a competitive soccer season.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the typical error, coefficients of variation, intra-class correlations and ratio limits of agreement were used to investigate test reliability of the YYIR1 test. The YYIR1 performance and all physiological responses have proven to be highly reliable in a sample of Belgian elite youth soccer players, aged between 13 and 18 years. The demonstrated high level of intermittent endurance capacity in all age groups may be used as reference values in well-trained adolescent soccer players.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to the parents and children who consented to participate in this study and to the directors and coaches of the participating Flemish soccer club, KAA Gent. The authors would like to thank the participating colleagues, Stijn Matthys, Valentijn Deneulin and Bert Celie for their help in collecting data. There has been no external financial assistance with this study.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bangsbo J, Iaia FM, Krustrup P. The yo-yo intermittent recovery test: A useful tool in evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. 2008;38:37–51. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krustrup P, Mohr M, Amstrup T, Rysgaard T, Johansen J, Steensberg A, Pedersen PK, Bangsbo J. The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test: Physiological response, reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:697–705. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000058441.94520.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deprez D, Coutts A, Lenoir M, Fransen J, Pion J, Philippaerts RM, Vaeyens R. Reliability and validity of the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 in young soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2014;32:903–910. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.876088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castagna C, Abt G, D’Ottavio S. Competitive-level differences in yo-yo intermittent recovery and twelve minute run test performance in soccer referees. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:805–809. doi: 10.1519/R-14473.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souhail H, Castagna C, Mohamed HY, Younes H, Chamari K. Direct validity of the yo-yo intermittent recovery test in young team handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:465–470. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c06827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castagna C, Impellizzeri F, Cecchini E, Rampinini E, Barbero Alvarez JC. Effects of intermittent-endurance fitness in match performance in young male soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:1954–1959. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b7f743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markovic G, Mikulic P. Discriminative ability of the yo-yo intermittent recovery test (level 1) in prospective young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;25:2931–2934. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318207ed8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deprez D, Vaeyens R, Coutts AJ, Lenoir M, Philippaerts RM. Relative age effect and yo-yo IR1 in youth soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:987–993. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. J Sports Sci. 1998;26:217–238. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas A, Dawson B, Goodman C. The yo-yo test: reliability and association with a 20m-run and VO2max. Int J Sports Physiol Perf. 2006;1:137–149. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.1.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castagna C, Manzi V, Impellizzeri F, Weston M, Barbero Alvarez JC. Relationship between endurance field tests and match performance in young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:3227–3233. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e72709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaeyens R, Malina RM, Janssens M, Van Renterghem B, Bourgois J, Vrijens J, Philippaerts RM. A multidisciplinary selection model for youth soccer: the Ghent Youth Soccer Project. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:928–934. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleiss JL. New York: Wiley; 1986. Reliability of measurements: The design and analysis of clinical experiments. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopkins WG. A new view of statistics. Available from: http://sportsci.org/resource/stats [Accessed 2014 July 4]

- 16.Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones AD, Bailey DA, Beunen GP. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:689–694. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malina RM, Eisenmann JC, Cumming SP, Ribeiro B, Aroso J. Maturity-associated variation in the growth and functional capacities of youth football (soccer) players 13-15 years. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91:555–562. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0995-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]