Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The clinical presentation and outcome of sarcoidosis varies by race. However, the race difference in mortality outcome remains largely unknown.

METHODS:

We studied mortality related to sarcoidosis from 1999 through 2010 by examining data on multiple causes of death from the National Center for Health Statistics. We compared the comorbid conditions between sarcoidosis-related deaths with deaths caused by car accidents (previously healthy control subjects) and rheumatoid arthritis (chronic disease control subjects) in both African Americans and Caucasians.

RESULTS:

From 1999 through 2010, sarcoidosis was reported as an immediate cause of death in 10,348 people in the United States with a combined overall mean age-adjusted mortality rate of 2.8 per 1 million person-years. Of these, 6,285 were African American and 3,984 Caucasian. The age-adjusted mortality rate for African Americans was 12 times higher than for Caucasians. African Americans died at an earlier age than Caucasians. African Americans living in the District of Columbia and North Carolina and Caucasians living in Vermont had higher mortality rates. Although the total sarcoidosis age-adjusted mortality rate had not changed over the 12 year period studied, this rate increased for Caucasians (R = 0.747, P = .005) but not for African Americans. Compared with the control groups, pulmonary hypertension was significantly more common in individuals with sarcoidosis.

CONCLUSIONS:

This nationwide population-based study exposes a significant difference in ethnicity and sex among people dying of sarcoidosis in the United States. Pulmonary hypertension investigation should be considered in all patients with sarcoidosis, especially African Americans.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease with an unknown etiology.1 Ethnicity plays an important role in sarcoidosis epidemiology, disease presentation, and clinical outcomes.2 The reported disease incidence is five in 100,000 for Caucasians and 39 in 100,000 for African Americans.3 The lifelong risk for the development of sarcoidosis is estimated to be 2.7% for African American women and 2.1% in African American men but only 1% for Caucasian women and 0.7% for Caucasian men.4 Sarcoidosis affects African Americans at a younger age than Caucasians, with a reported peak incidence one decade earlier than in Caucasians.4

African Americans with sarcoidosis have a higher rate of hospital admission than Caucasians.5,6 Additionally, remarkable differences exist in the clinical presentation of sarcoidosis between African Americans and Caucasians. Sarcoidosis is more often symptomatic in African Americans.7 African Americans experience more extrapulmonary sarcoidosis, more often affecting the skin, bone marrow, and eyes,8,9 and have a higher likelihood of decreasing FVC in the course of pulmonary sarcoidosis.10 As such, African Americans experience worse prognosis, more multiorgan involvement, and a higher rate of hospitalization.11‐13 Despite several health disparities analyses focusing on the epidemiology and prognosis of sarcoidosis, few studies have evaluated the role of this difference plays in mortality.12,14

In this study, we hypothesized that African Americans with sarcoidosis have a higher mortality rate, which increased in the past decade. We examined the trend of the sarcoidosis-related mortality rate in African Americans and Caucasians over 12 years and compared comorbidities with representative control groups of previously healthy people defined as those who died as a result of car accidents and chronically ill people defined as those who died of rheumatoid arthritis.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois at Chicago approved a waiver for this study (IRB number 2014-0418). This retrospective, population-based study compared data on immediate cause of death based on US death certificates from 1999 to 2010. The data were obtained from the WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) online databases prepared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.15 Death certificates list a single underlying cause of death (the immediate cause of death), up to 20 comorbidities, and demographic information.16 Diseases and related conditions reported on the death certificate are coded in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), since 1999.17

Study Variables

Variables included in the analysis were age, sex, race/ethnicity, year of death, cause of death, and comorbid conditions. Race/ethnicity was categorized according to US Census standards as non-Hispanic white, Asian-Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic black (black), and American Indian-Alaska Native (Native American). The study population was defined as non-Hispanic African American and non-Hispanic Caucasian. Age at death was classified into the clustered age-groups.

Study Definitions

Sarcoidosis-related mortality was defined as the immediate cause of death from pulmonary or extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. This included all observations that assigned any of the ICD-10 D86 codes as the immediate cause of death.

Two control groups were selected: pedestrians who died in traffic accidents, representing a healthy population, and people who died of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis, like sarcoidosis, is a chronic inflammatory disease with a higher prevalence in African Americans and women. In addition, both diseases are usually treated with similar medications. Traffic accident-related deaths were defined by an immediate cause of death with ICD-10 codes of V01 to V09. Seropositive and seronegative rheumatoid arthritis-related deaths were defined by an immediate cause of death with ICD-10 codes M05 and M06.0. Comorbidities were defined with the following ICD-10 codes: pneumonia, J09-J18; acute respiratory failure, J96.0; nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, A31; TB, A16 to A19; COPD, J44; pulmonary hypertension, I27.0 and I27.2; diabetes, E10 to E14; heart failure, I50; chronic renal failure, N18; dementia (vascular, F01; Alzheimer, G30); asthma, J45; HIV infection, B20 to B24; neoplasm, C00-D48; hepatic failure, K70.4 and K72.0; and pulmonary fibrosis, J84.

Statistical Analysis

Counts and percentages were examined as predictors using crude ORs and χ2 test or, as appropriate, Mantel-Haenszel, exact, or two-sided analysis of variance tests. The crude mortality rate was not primarily used in this study because of the potential misleading information resulting from comparing rates over time in various age-groups. Age-adjusted mortality rates were used to calculate relative mortality risk among groups and over time. Age-adjusted death rates were calculated by weighting averages of the age-specific rates and comparing with relative mortality risk among 2,000 US standard populations. The equation for the age-adjusted death rate calculation was R′ = Σi(Psi/Ps)Ri, where Psi is the standard population for age-group, and i and Ps are the total standard population (all ages combined).15 Linear regression and exponential growth regression model analysis were performed to evaluate the trend of age-adjusted rates of sarcoidosis-related mortality from 1999 to 2010.

To examine comorbid conditions, we compared decedents aged > 35 years with sarcoidosis with traffic accident- and rheumatoid arthritis decedents in the same age-group from 1999 to 2010 and calculated crude OR and CI comparisons of selected comorbidities. For all statistical analyses, a two-tailed P < .05 was considered significant.

A total of 70,494 pedestrians died in traffic-related accidents during the study period. There were 7,723 non-Hispanic African American (women, 2,066; men, 5,657) and 28,295 non-Hispanic Caucasian (women, 9,240; men, 19,055) decedents aged > 35 years used as control subjects.

Rheumatoid arthritis was reported as the immediate cause of death in 29,997 (women, 22,935; men, 7,062) individuals. There were 1,881 non-Hispanic African American (women, 1,469; men, 412) and 2,860 non-Hispanic Caucasian (women, 1,941; men, 919) decedents aged > 35 years used as control subjects.

Data are suppressed by the National Center for Health Statistics when a category has < 10 people for confidentiality reasons. Death rates are labeled as unreliable when the numerator is < 21. All analyses were performed using the statistical software packages SPSS, version 21 (IBM Corporation) and GraphPad Prism, version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc).

Results

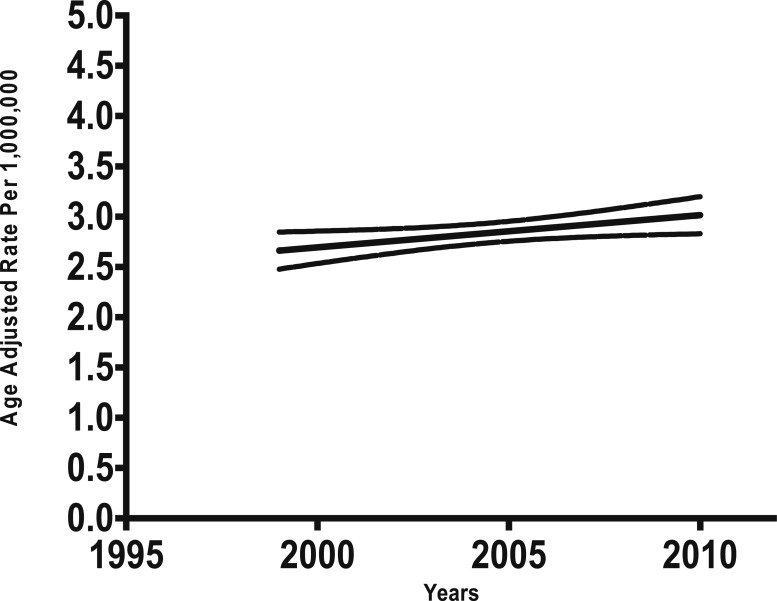

From the 29,176,040 deaths occurring from 1999 to 2010, sarcoidosis was recorded as immediate cause of death in 10,348 decedents. From those, 6,264 were non-Hispanic African Americans, 3,761 non-Hispanic Caucasians, 246 Hispanic, 23 American Indian or Alaska Native, and 54 Asian or Pacific Islander. The total age-adjusted rate of sarcoidosis-related deaths was 2.8 per 1 million population, which did not change during the 12-year study period (R = 0.424, P = .169) (Fig 1). However, the age-adjusted rate of sarcoidosis-related deaths in Caucasians significantly increased over the same period (R = 0.747, P = .005). This increasing rate was not observed in African Americans (P > .05).

Figure 1 –

Total age-adjusted rate of sarcoidosis-related deaths in the United States, 1999 to 2010.

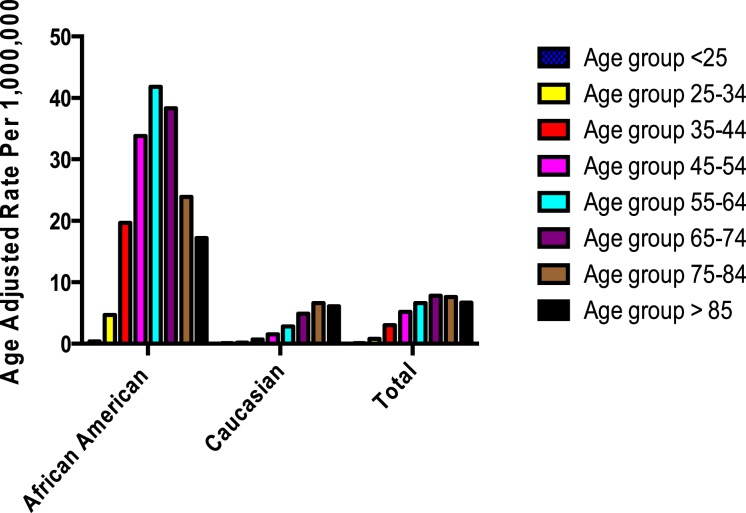

There was a remarkable difference in age frequency in mortality rates per race. In patients aged > 55 years, 5,527 died of sarcoidosis (crude rate, 7.7 per 1 million population). From those, 2,672 were African American (crude rate, 37 per 1 million population) and 2,855 Caucasian (crude rate, four per 1 million population). The crude mortality rates for non-Hispanic African Americans in the age-groups 55 to 64, 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and > 85 years were 42, 38, 24, and 17 per 1 million population, respectively. Crude mortality rates for non-Hispanic Caucasians in those age-groups were three, five, seven, and six per 1 million population, respectively (P = .0003 comparing African Americans with Caucasians). Figures 2 and 3 show the crude mortality rate per 1 million population stratified by age-group and ethnicity. Sex-adjusted mortality rates were higher in women (6,457 women died; age-adjusted mortality rate, 3.3) than in men (3,891 men died; age-adjusted mortality rate, 2.3) (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02-1.20; P = .0136) (Table 1).

Figure 2 –

Age-adjusted rate per 1 million stratified per race and age-group in the United States, 1999 to 2010.

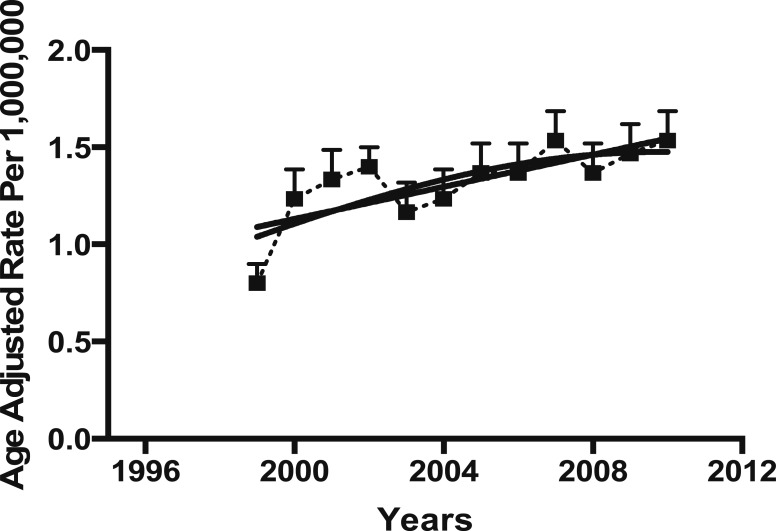

Figure 3 –

Age-adjusted rate of sarcoidosis-related deaths in Caucasians in the United States, 1999 to 2010.

TABLE 1 ] .

Sarcoidosis-Related Death Stratified per Sex and Race

| Sex | No. Patients | Crude Rate | Age-Adjusted Ratea |

| Total sarcoidosis-related death | |||

| Female | 6,457 | 0.359 | 3.3 (3.3-3.4) |

| Male | 3,891 | 0.224 | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) |

| Total | 10,348 | 0.293 | 2.8 (2.8-2.9) |

| Sarcoidosis-related death in African Americans | |||

| Female | 3,962 | 17 | 18.5 (17.9-19) |

| Male | 2,285 | 10.8 | 12.7 (12.1-13.2) |

| Total | 6,247 | 14 | 16 (15.6-16.4) |

| Sarcoidosis-related death in Caucasians | |||

| Female | 2,300 | 1.9 | 1.5 (1.4-1.5) |

| Male | 1,451 | 1.2 | 1.1 (1.1-1.2) |

| Total | 3,984 | 1.6 | 1.3 (1.3-1.3) |

Per 1 million population (95% CI).

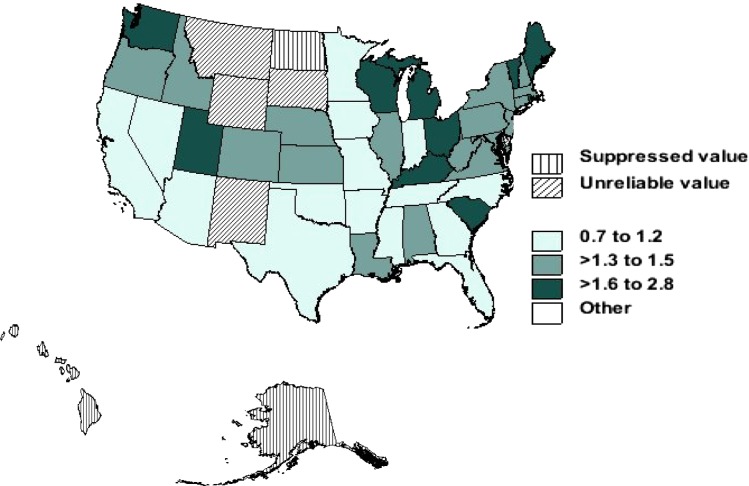

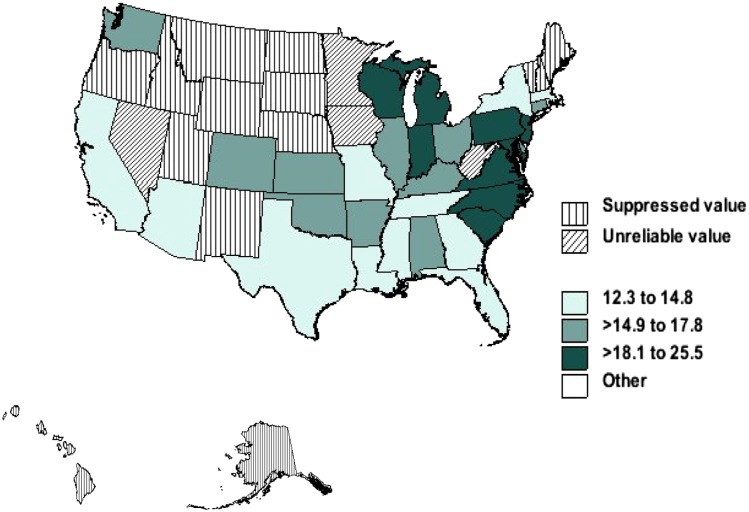

Figures 4 and 5 show age-adjusted mortality rates per 1 million person-years in non-Hispanic African American and Caucasian decedents with sarcoidosis by state from 1999 to 2010. The highest age-adjusted mortality rate for Caucasians with sarcoidosis was reported in Vermont (three per 1 million person-years) and the lowest in Arizona (one per 1 million person-years). However, this distribution was different for African Americans. The highest age-adjusted rate for African Americans was recorded in the District of Columbia (26 per 1 million person-years) and lowest in Arizona (12 per 1 million person-years).

Figure 4 –

Age-adjusted mortality rates per 1 million person-years in non-Hispanic Caucasian decedents with sarcoidosis by state, United States, 1999 to 2010.

Figure 5 –

Age-adjusted mortality rates per 1 million person-years in non-Hispanic African American decedents with sarcoidosis by state, United States, 1999 to 2010.

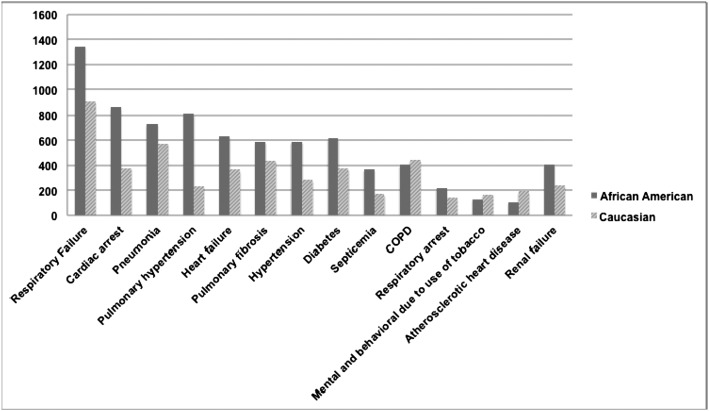

Respiratory failure was reported as the most common underlying cause of death among those with sarcoidosis during the study period, after excluding unclassified individuals. Figure 6 shows the causes of death per race. Comorbidities in sarcoidosis were compared with that of pedestrian (Table 2) and rheumatoid arthritis (Table 3) decedents.

Figure 6 –

Multiple cause of death in Caucasians and African Americans with sarcoidosis in the United States, 1999 to 2010.

TABLE 2 ] .

Comparison of Comorbid Conditions in Sarcoidosis-Related Deaths (Case Subjects) With Pedestrians Who Died in Traffic Accidents (Control Subjects) in the United States From 1999 to 2010

| African American | Caucasian | |||||

| Comorbidity | Case Subjects | Control Subjects | P Value, OR (95% CI) | Case Subjects | Control Subjects | P Value, OR (95% CI) |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Female | 476 | 9 | … | 344 | 85 | … |

| Male | 233 | 53 | … | 216 | 211 | … |

| Total | 709 (11) | 62 (0.8) | < .00001, 17 (13-22) | 560 (15) | 296 (1) | < .00001, 17 (15-20) |

| Acute respiratory failure | ||||||

| Female | 118 | 1 | … | 73 | 6 | … |

| Male | 45 | 1 | … | 44 | 6 | … |

| Total | 163 (3) | 2 (0.1) | < .00001, 109 (27-440) | 117 (3) | 12 (0.04) | < .00001, 77 (43-141) |

| NTM | ||||||

| Female | 9 | 0 | … | 9 | 0 | … |

| Male | 6 | 0 | … | 3 | 0 | … |

| Total | 15 (0.2) | 0 | < .00001 | 12 (0.3) | 0 | < .00001 |

| TB | ||||||

| Female | 7 | 1 | … | 2 | 0 | … |

| Male | 6 | 0 | … | 1 | 0 | … |

| Total | 13 (0.2) | 1 (0.01) | .0002, 17 (2-130) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | < .00001 |

| COPD | ||||||

| Female | 242 | 1 | … | 282 | 34 | … |

| Male | 160 | 11 | … | 160 | 87 | … |

| Total | 402 (7) | 12 (2) | < .00001, 47 (26-83) | 442 (12) | 121 (0.4) | < .00001, 32 (26-39) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | ||||||

| Female | 589 | 0 | … | 159 | 0 | … |

| Male | 205 | 0 | … | 73 | 2 | … |

| Total | 794 (13) | 0 | < .00001 | 232 (6) | 2 | < .00001, 896 (238-3,847) |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Female | 403 | 8 | … | 242 | 48 | … |

| Male | 199 | 31 | … | 130 | 111 | … |

| Total | 602 (10) | 39 (0.5) | < .00001, 22 (16-31) | 372 (10) | 159 (0.6) | < .00001, 20 (17-24) |

| Heart failure | ||||||

| Female | 396 | 1 | … | 234 | 17 | … |

| Male | 218 | 4 | … | 129 | 46 | … |

| Total | 614 (10) | 5 (0.6) | < .00001, 178 (74-430) | 363 (10) | 63 (0.2) | < .00001, 49 (38-65) |

| Chronic renal failure | ||||||

| Female | 87 | 5 | … | 28 | 3 | … |

| Male | 51 | 6 | … | 32 | 13 | … |

| Total | 138 (2) | 11 (1) | < .00001, 17 (9-31) | 60 (1.6) | 16 (0.6) | < .00001, 29 (17-51) |

| Dementia | ||||||

| Female | 6 | 5 | … | 13 | 24 | … |

| Male | 2 | 15 | … | 3 | 29 | … |

| Total | 8 (0.1) | 20 (0.3) | .11 | 16 (0.4) | 53 (0.2) | .0022, 2 (1.3-4) |

| Asthma | ||||||

| Female | 96 | 1 | … | 48 | 5 | … |

| Male | 38 | 0 | … | 12 | 2 | … |

| Total | 134 (2) | 1 (0.01) | < .00001, 179 (25-1,277) | 60 (1.6) | 7 (0.02) | < .00001, 67 (31-147) |

| HIV | ||||||

| Female | 8 | 3 | … | 1 | 0 | … |

| Male | 6 | 7 | … | 3 | 3 | … |

| Total | 14 (0.2) | 10 (0.1) | .14 | 4 (0.1) | 3 (0.01) | .0001, 10 (2-46) |

| Neoplasm | ||||||

| Female | 83 | 3 | … | 91 | 17 | … |

| Male | 42 | 10 | … | 69 | 50 | … |

| Total | 125 (2) | 13 (0.2) | < .00001, 13 (7-23) | 160 (4) | 67 (0.2) | < .00001, 19 (14-26) |

| Hepatic failure | ||||||

| Female | 41 | 0 | … | 26 | 3 | … |

| Male | 21 | 0 | … | 19 | 10 | … |

| Total | 62 (1) | 0 | < .00001 | 45 (1.2) | 13 (0.05) | < .000001, 27 (15-50) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | ||||||

| Female | 391 | 0 | … | 285 | 5 | … |

| Male | 185 | 0 | … | 151 | 4 | … |

| Total | 576 (10) | 0 | < .00001 | 436 (12) | 9 (0.03) | < .00001, 424 (219-822) |

Data are presented as No. and No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. NTM = nontuberculous mycobacteria.

TABLE 3 ] .

Comparison of Comorbid Conditions in Sarcoidosis-Related Deaths (Case Subjects) With Rheumatoid Arthritis-Related Deaths (Control Subjects) in the United States From 1999 to 2010

| Comorbidity | African American | Caucasian | ||||

| Case Subjects | Control Subjects | P Value, OR (95% CI) | Case Subjects | Control Subjects | P Value, OR (95% CI) | |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Female | 476 | 321 | … | 344 | 371 | … |

| Male | 233 | 93 | … | 216 | 195 | … |

| Total | 709 (11) | 414 (22) | < .00001, 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 560 (15) | 566 (20) | < .00001, 0.73 (0.64-0.83) |

| Acute respiratory failure | ||||||

| Female | 118 | 33 | … | 73 | 59 | … |

| Male | 45 | 6 | … | 44 | 20 | … |

| Total | 163 (3) | 39 (2) | .1 | 117 (3) | 79 (2.7) | .31 |

| NTM | ||||||

| Female | 9 | 2 | … | 9 | 2 | … |

| Male | 6 | 0 | … | 3 | 3 | … |

| Total | 15 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | .2 | 12 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | .2 |

| TB | ||||||

| Female | 7 | 0 | … | 2 | 2 | … |

| Male | 6 | 2 | … | 1 | 1 | … |

| Total | 13 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | .3 | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | .7 |

| COPD | ||||||

| Female | 242 | 79 | … | 282 | 178 | … |

| Male | 160 | 37 | … | 160 | 123 | … |

| Total | 402 (7) | 116 (6) | .4 | 442 (12) | 301 (11) | .052 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | ||||||

| Female | 589 | 42 | … | 159 | 28 | … |

| Male | 205 | 4 | … | 73 | 16 | … |

| Total | 794 (13) | 46 (2) | < .00001, 6 (5-8) | 232 (6) | 44 (2) | < .00001, 5 (4-7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Female | 403 | 115 | … | 242 | 125 | … |

| Male | 199 | 51 | … | 130 | 76 | … |

| Total | 602 (10) | 166 (9) | .09 | 372 (10) | 201 (7) | < .00001, 1.5 (1.3-1.8) |

| Heart failure | ||||||

| Female | 396 | 142 | … | 234 | 242 | … |

| Male | 218 | 25 | … | 129 | 109 | … |

| Total | 614 (10) | 167 (9) | .06 | 363 (10) | 351 (12) | .0024, 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| Chronic renal failure | ||||||

| Female | 87 | 32 | … | 28 | 20 | … |

| Male | 51 | 17 | … | 32 | 8 | … |

| Total | 138 (2) | 49 (2.6) | .5 | 60 (1.6) | 28 | … |

| Dementia | ||||||

| Female | 6 | 15 | … | 13 | 15 | … |

| Male | 2 | 7 | … | 3 | 3 | … |

| Total | 8 (0.1) | 22 (1.2) | < .00001, 0.1 (0.05-0.3) | 16 (0.4) | 18 (1) | .3 |

| Asthma | ||||||

| Female | 96 | 17 | … | 48 | 18 | … |

| Male | 38 | 1 | … | 12 | 2 | … |

| Total | 134 (2) | 18 (1) | .0004, 2 (1-4) | 60 (1.6) | 20 (0.7) | .0006, 2.4 (1.4-3.9) |

| HIV | ||||||

| Female | 8 | 1 | … | 1 | 0 | … |

| Male | 6 | 0 | … | 3 | 0 | … |

| Total | 14 (0.2) | 1 (0.05) | .1 | 4 (0.1) | 0 | .07 |

| Neoplasm | ||||||

| Female | 83 | 21 | … | 91 | 51 | … |

| Male | 42 | 21 | … | 69 | 44 | … |

| Total | 125 (2) | 42 (2) | .7 | 160 (4) | 95 (3) | .03, 1.3 (1.03-1.72) |

| Hepatic failure | ||||||

| Female | 41 | 4 | … | 26 | 0 | … |

| Male | 21 | 0 | … | 19 | 1 | … |

| Total | 62 (1) | 4 (0.2) | .0006, 5 (2-14) | 45 (1.2) | 1 (0.03) | < .00001, 36 (5-258) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | ||||||

| Female | 391 | 182 | … | 285 | 198 | … |

| Male | 185 | 59 | … | 151 | 142 | … |

| Total | 576 (10) | 241 (13) | .0001, 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 436 (12) | 340 (12) | .9 |

Data are presented as No. or No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. See Table 2 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Comparison of Sarcoidosis and Pedestrian Traffic Accident Groups

Although the mean age of the sarcoidosis group was older than the pedestrian traffic-accident group, all aged > 35 years, no significant difference was observed between the two groups (R = 0.173, P = .57). As shown in Table 2, acute respiratory failure, asthma, neoplasm, and pulmonary fibrosis were significantly higher in both African American and Caucasian sarcoidosis decedents. Dementia and HIV infection frequencies in African American individuals were the only comorbidities in which no significant difference between the sarcoidosis and pedestrian traffic accident groups was observed.

Twenty-four malignant neoplasms of bronchus and lung were reported in African American and Caucasian decedents with sarcoidosis (four and eight African American men and women, respectively, and eight and four Caucasian men and women, respectively). Among the pedestrian traffic accident group, 17 individuals had lung cancer (one African American man and 11 and five Caucasian men and women, respectively). Significant differences were found in the frequency of lung cancer between pedestrian traffic accident and sarcoidosis decedents (OR, 16 [P = .0004] and 6 [P < .0001] for African Americans and Caucasians, respectively).

Comparison of Sarcoidosis and Rheumatoid Arthritis Groups

Compared with rheumatoid arthritis decedents, conditions such as pulmonary hypertension, asthma, and hepatic failure were significantly more common in both African American and Caucasian decedents with sarcoidosis (Table 3). However, Caucasians in the sarcoidosis group were less likely to have diabetes and neoplasm but more likely to have heart failure than Caucasians in the rheumatoid arthritis group. African Americans in the sarcoidosis group were less likely to have dementia and pulmonary fibrosis than African Americans in the rheumatoid arthritis group. The comorbid conditions were compared between African American and Caucasian decedents aged > 35 years with sarcoidosis (Table 4). Pulmonary fibrosis was reported to be significantly more common in Caucasian decedents; however, pulmonary hypertension was significantly more common in African American decedents.

TABLE 4 ] .

Comparison of Comorbid Conditions in Sarcoidosis-Related Deaths Stratified Based on Race in the United States From 1999 to 2010

| Comorbidity | African American | Caucasian | P Value | OR (95% CI) |

| Pneumonia | ||||

| Female | 476 | 344 | … | … |

| Male | 233 | 216 | < .00001 | 0.75 (0.85-0.67) |

| Total | 709 (11) | 560 (15) | … | … |

| Acute respiratory failure | ||||

| Female | 118 | 73 | … | … |

| Male | 45 | 44 | .21 | … |

| Total | 163 (3) | 117 (3) | … | … |

| NTM | ||||

| Female | 9 | 9 | … | … |

| Male | 6 | 3 | .50 | … |

| Total | 15 (0.2) | 12 (0.3) | … | … |

| TB | ||||

| Female | 7 | 2 | … | … |

| Male | 6 | 1 | .1 | … |

| Total | 13 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | … | … |

| COPD | ||||

| Female | 242 | 282 | … | … |

| Male | 160 | 160 | < .00001 | 0.53 (0.61-0.46) |

| Total | 402 (7) | 442 (12) | … | … |

| Pulmonary hypertension | ||||

| Female | 589 | 159 | … | … |

| Male | 205 | 73 | < .00001 | 2 (2-3) |

| Total | 794 (13) | 232 (6) | … | … |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| Female | 403 | 242 | … | … |

| Male | 199 | 130 | .9 | … |

| Total | 602 (10) | 372 (10) | … | … |

| Heart failure | ||||

| Female | 396 | 234 | … | … |

| Male | 218 | 129 | .4 | … |

| Total | 614 (10) | 363 (10) | … | … |

| Chronic renal failure | ||||

| Female | 87 | 28 | … | … |

| Male | 51 | 32 | .02 | 1.43 (1.05-1.94) |

| Total | 138 (2) | 60 (1.6) | … | … |

| Dementia | ||||

| Female | 6 | 13 | … | … |

| Male | 2 | 3 | .004 | 0.31 (0.13-0.72) |

| Total | 8 (0.1) | 16 (0.4) | … | … |

| Asthma | ||||

| Female | 96 | 48 | … | … |

| Male | 38 | 12 | .03 | 1.3 (1.02-1.89) |

| Total | 134 (2) | 60 (1.6) | … | … |

| HIV | ||||

| Female | 8 | 1 | … | … |

| Male | 6 | 3 | .16 | … |

| Total | 14 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | … | … |

| Neoplasm | ||||

| Female | 83 | 91 | … | … |

| Male | 42 | 69 | < .00001 | 0.47 (0.37-0.60) |

| Total | 125 (2) | 160 (4) | … | … |

| Hepatic failure | ||||

| Female | 41 | 26 | … | … |

| Male | 21 | 19 | .40 | … |

| Total | 62 (1) | 45 (1.2) | … | … |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | ||||

| Female | 391 | 285 | … | … |

| Male | 185 | 151 | .0007 | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| Total | 576 (10) | 436 (12) | … | … |

Data are presented as No. and No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. See Table 2 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Discussion

We found a remarkable race difference in sarcoidosis-related mortality in the United States and demonstrate that age-adjusted mortality rates remained flat during the 12-year study period. Although age-adjusted mortality does not seem to be increasing in the African American population, this trend was observed in the Caucasian population.

Pulmonary hypertension and airway diseases were more common in sarcoidosis decedents than in a representative group of the healthy population and that with rheumatoid arthritis. Furthermore, African Americans with sarcoidosis had a higher risk for pulmonary hypertension than Caucasians with sarcoidosis.

Swigris et al12 found that the age-adjusted sarcoidosis mortality rate increased by 50% from 1988 to 2007 in the United States. The current study supports these findings only for Caucasians.

In the current study, the total age-adjusted mortality rate was 2.8 per 1 million population from 1999 to 2010, which has not significantly changed. However, this figure has increased from one per million of the population in 1958 to 1.6 in 1979, 2.1 in 1991, and 2.8 in 2010.14,18

The increasing trend of Caucasian age-adjusted mortality needs further investigation. Several explanations exist for this alarming trend. One possibility is increasing awareness and improved diagnosis of sarcoidosis in Caucasians. Higher clinical suspicion coupled with the increasingly common use of advanced medical technology in Caucasians than in African Americans over the 12-year study period could explain why more cases were detected in whites. Sarcoidosis appears to be more common in Caucasians than in African Americans in older age-groups, which may have resulted in a relative increase in the exposure of sarcoidosis in Caucasians than in African Americans over the 12-year study period, especially in elderly individuals.

The overall rate of mortality due to sarcoidosis was eightfold higher in African Americans than in Caucasians. Gideon and Mannino14 and Reich19 reported a 14-fold increase. This difference may be partly due to an increased proportion of the Caucasian mortality rate in the current study. Sarcoidosis is more common in African Americans than in Caucasians (3-4:1 incidence ratio).20 This trend was shown in African ethnicity in other countries as well.21,22 The reason for this racial susceptibility remains unclear.

The age-adjusted mortality rate is 66% higher among women than men. Gillum,23 who studied sarcoidosis-related hospitalization and mortality in the United States from 1968 to 1984, demonstrated that African American women had a higher age-adjusted mortality rate than men. Swigris et al12 reported a higher mortality rate for women aged 30 to 80 years. Rybicki et al20 noted that women are 1.1 to 1.5 times more likely to receive a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, regardless of ethnicity, which may explain some but not all of the higher risk for mortality in women.

Overall, the distribution of sarcoidosis mortality was similar to its prevalence in terms of geography and race, although there were some exceptions. The highest age-adjusted mortality rate for Caucasians with sarcoidosis was in New England states, including Vermont, Rhode Island, and Maine, as well as in Utah and Washington. Mortality rates were lowest in Arizona, Oklahoma, and Nevada. This distribution, however, was different for African Americans. The highest age-adjusted rate for African Americans was seen in the District of Columbia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and New Jersey. The lowest rate was found in Florida, Texas, and Arizona. This difference in race-related mortality distribution could be partially explained by general racial population distribution in the United States.24 Other explanations include environment exposures, occupational exposures, and health-care disparities. It may simply be a reflection of the sarcoidosis prevalence in the various states.

Pulmonary complication was the most common comorbidity reported as a cause of death across all subjects with sarcoidosis. Respiratory failure was the most common single reported cause of death among patients with sarcoidosis. In their study, Gideon and Mannino14 found the same result that was in contrast with a report from Japan, which reported cardiac complications of sarcoidosis as the most common cause of death, accounting for 77% of sarcoidosis-related mortality.

Common comorbidities, including diabetes and hypertension, were reported in sarcoidosis decedents. Although it is not possible to assign an etiology from this study, sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory state that is treated with corticosteroids, which increases the risk for these comorbidities as well as many others. As commonly noted, the likelihood for comorbidities increases with age and is more frequently observed in African Americans.25,26

Poor outcome in pulmonary sarcoidosis is associated with interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension.27 Pulmonary hypertension has been reported to occur in sarcoidosis in 5% to 6% of people while at rest and in 43% during exercise.28,29 This may occur with or without left ventricular dysfunction.30 In the current study, we found that pulmonary hypertension was reported more commonly in African American decedents and pulmonary fibrosis in Caucasian decedents with sarcoidosis. Pulmonary hypertension was twofold higher in African Americans. This finding raises the question of whether African Americans experience more extensive granulomatous inflammation in the lung vasculature or whether their lung vasculature reacts more intensely to inflammation. However, Caucasians with sarcoidosis had a 20% higher rate of pulmonary fibrosis than African Americans with sarcoidosis. The reason for this finding is unclear, although it could be only a duration effect. We showed that Caucasians survived longer with sarcoidosis than African Americans. Therefore, fibrosis formation in the lungs had a longer time interval in the Caucasian population. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis of Swigris et al12 that age is a risk factor for pulmonary fibrosis in sarcoidosis. Although pulmonary hypertension may be linked to pulmonary fibrosis, it has been shown that it also occurs with near-normal lung function tests.31 Pulmonary hypertension has been shown to be responsive to medications used to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension.32,33

The main limitation of the current study is the reliance on data from death certificates, which has been noted previously.16 Clinicians may underreport or overreport causes of death as well as comorbidities. Additionally, incorrect coding may occur with primary and secondary diagnoses, and ethnicity may not be documented correctly. These limitations notwithstanding, death certificate data from the National Center for Health Statistics are critical for the evaluation disease-related mortality on a population level.34 Lead time bias is a potential confounder to the increased mortality rates in African Americans. Sarcoidosis was diagnosed 10 years earlier in African Americans than in Caucasians; thus, this longer period of exposure might explain the increased mortality rate. Detection bias contributing to the apparent increase in the prevalence of sarcoidosis and related mortality is another concern in this study. Because many cases of sarcoidosis are misdiagnosed or are subclinical, it is likely that the actual rate of sarcoidosis-related mortality is slightly higher than that reported in the National Center for Health Statistics registry.

This population-based study shows the existence of a significant difference in ethnicity and sex among sarcoidosis decedents in the United States. African American women with sarcoidosis die at a higher rate and at a younger age than Caucasians. Pulmonary hypertension is a lethal complication in patients with sarcoidosis, especially among African Americans. These findings should influence research in the areas of health disparities and disease process among various racial groups and between the sexes.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: M. M. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M. M. contributed to the study concept and design, hypotheses delineation, and data analysis and interpretation and M. M., R. F. M., D. S., N. J. S., and R. P. B. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following conflicts of interest: Dr Sweiss received grants from Genentech, Inc. Dr Baughman has received grants from Genentech, Inc, and received research grants in sarcoidosis from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; Celgene Corporation; Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc; Cephalon, Inc; and Gilead. He has received consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline plc and Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc. Drs Mirsaeidi, Machado, and Schraufnagel have reported that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the study design, data analysis, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ICD-10

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant [5 T32 HL 82547-7].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305(4):391-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westney GE, Judson MA. Racial and ethnic disparities in sarcoidosis: from genetics to socioeconomics. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27(3):453-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(2):736-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Jr, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(3):234-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen ER. Re: “Geographic variation in sarcoidosis in South Carolina: its relation to socioeconomic status and health care indicators.” Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(9):938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kajdasz DK, Judson MA, Mohr LC, Jr, Lackland DT. Geographic variation in sarcoidosis in South Carolina: its relation to socioeconomic status and health care indicators. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(3):271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sartwell PE, Edwards LB. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in the US Navy. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;99(4):250-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. ; Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS) Research Group. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 pt 1):1885-1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minus HR, Grimes PE. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32(4):361-363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Thompson BW, et al. ; ACCESS Research Group. Two year prognosis of sarcoidosis: the ACCESS experience. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20(3):204-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Kamugisha L, Westney GE. Hospitalization for patients with sarcoidosis: 1979-2000. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23(2):124-129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swigris JJ, Olson AL, Huie TJ, et al. Sarcoidosis-related mortality in the United States from 1988 to 2007. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(11):1524-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerke AK, Yang M, Tang F, Cavanaugh JE, Polgreen PM. Increased hospitalizations among sarcoidosis patients from 1998 to 2008: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gideon NM, Mannino DM. Sarcoidosis mortality in the United States 1979-1991: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):423-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER website. http://wonder.cdc.gov. Accessed June 15, 2014.

- 16.Mirsaeidi M, Machado RF, Garcia J, Schraufnagel DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease mortality in the United States, 1999-2010: a population-based comparative study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple cause of death 1999-2011. CDC WONDER website. http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/mcd.html. Accessed July 21, 2013.

- 18.Moriyama IM. Mortality from sarcoidosis in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1961;84(5 pt 2):116-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reich JM. Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis in African-Americans versus Caucasians. Eur Respir J. 2001;17(4):833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rybicki BA, Maliarik MJ, Major M, Popovich J, Jr, Iannuzzi MC. Epidemiology, demographics, and genetics of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1998;13(3):166-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geographical variations in the incidence of sarcoidosis in Great Britain: a comparative study of four areas. A report to the Research Committee of the British Thoracic and Tuberculosis Association. Tubercle. 1969;50(3):211-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benatar SR. Sarcoidosis in South Africa. A comparative study in whites, blacks and coloureds. S Afr Med J. 1977;52(15):602-606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillum RF. Sarcoidosis in the United States—1968 to 1984. Hospitalization and death. J Natl Med Assoc. 1988;80(11):1179-1184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Population distribution by race/ethnicity (based on Census Bureau’s March 2012 and 2013 current population surveys). The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-raceethnicity. Accessed June 15, 2014.

- 25.Perez A, Jansen-Chaparro S, Saigi I, Bernal-Lopez MR, Miñambres I, Gomez-Huelgas R. Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. J Diabetes. 2014;6(1):9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boruchowicz A, Maunoury V, Crinquette JF, Cappoen JP. Diabetes: an ignored complication of sarcoidosis? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(4):681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh SL, Wells AU, Sverzellati N, et al. An integrated clinicoradiological staging system for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(2):123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handa T, Nagai S, Miki S, et al. Incidence of pulmonary hypertension and its clinical relevance in patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2006;129(5):1246-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Głuskowski J, Hawryłkiewicz I, Zych D, Wojtczak A, Zieliński J. Pulmonary haemodynamics at rest and during exercise in patients with sarcoidosis. Respiration. 1984;46(1):26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baughman RP, Engel PJ, Taylor L, Lower EE. Survival in sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: the importance of hemodynamic evaluation. Chest. 2010;138(5):1078-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maimon N, Salz L, Shershevsky Y, Matveychuk A, Guber A, Shitrit D. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension in patients with near-normal lung function. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(3):406-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baughman RP, Culver DA, Cordova FC, et al. Bosentan for sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: a double-blind placebo controlled randomized trial. Chest. 2014;145(4):810-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Judson MA, Highland KB, Kwon S, et al. Ambrisentan for sarcoidosis associated pulmonary hypertension. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2011;28(2):139-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in US Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(8):881-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]