Sir,

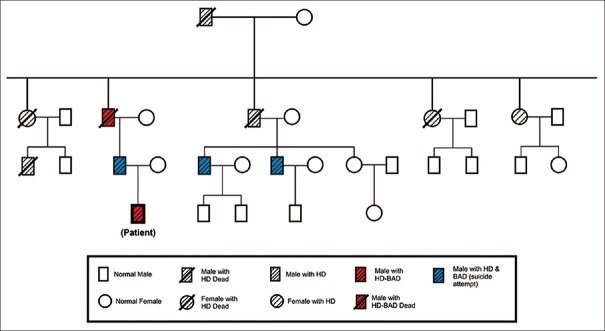

Huntington's disease (HD) is inherited autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder that results from an unstable expansion of trinucleotide repeat cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) of the huntingtin gene IT-15 on chromosome 4p16.3. It is characterized by movement disorders (usually chorea), cognitive impairment (resulting in dementia) and psychiatric disorders. Symptoms typically begin in the fourth decade of life and result in progressive deterioration in functional capacity and independence. The association of mood disorder appears confined in certain families, suggesting genetic heterogeneity within HD.[1,2] Psychiatric changes are often present before the development of chorea or intellectual impairment. In our case, the patient had a positive family history of HD in three successive generations. Here, we report a case of 17-year-old male patient who presented to neurology out-patient department (OPD) with complaints of increased blinking of eyes for 8 months and continuous jerky involuntary movements of left foot for 1 month. Genetic analysis showed CAG repeat expansion – 60 units and thus patient was diagnosed to be suffering from HD. Patient was referred to psychiatry OPD for his behavioral complaints and was subsequently admitted to our psychiatric ward. The members of patient's family complained that for the last 3 months he was having irritable behavior, frequent fights, remained restless, abstained frequently from school, reduced sleep and gradually started boasting about self, talking more than usual, his speech was loud, interjected with rhyming and punning and sometimes complained that other people make gestures and pass comments on him, though he denied hearing any voices. One year prior to the current hospitalization, patient complained of sadness of mood, loss of energy, loss of appetite and sleep and had these symptoms lasted for 6 months, but did not consult any specialist and these were resolved gradually. There is a strong family history of HD comprising 11 cases in three successive generations [Figure 1]. Of these 11 cases of HD in the family, five cases had comorbid bipolar affective disorder with one of them committing suicide. Patient was diagnosed as having HD with bipolar affective disorder currently episode manic with psychosis (F31.2). On Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), baseline score was 32 and Clinical Global Impression (CGI-severity score) was 6. Treatment was started with divalproate 1500 mg/day as a mood stabilizer, haloperidol (10 mg/day) for psychotic symptoms and lorazepam 4 mg/day for inducing sleep. After 4 weeks, there was a satisfactory response (with 50% reduction) in psychiatric symptoms as assessed on YMRS scale score of 17 and CGI- global improvement score of 2. In addition to pharmacotherapy, patient also received individual supportive psychotherapy. After 4 weeks of treatment, there was improvement in patient's condition, his mood stabilized, and he was no longer delusional. He was discharged and now remains in outdoor patient treatment with a long-term follow-up plan for medical care, psychological, genetic, family counseling and emerging benefit of striatal fetal neurotransplantation.

Figure 1.

Pedigree chart of Huntington's disease with bipolar affective disorder

In our 17-year-old patient, psychiatric changes have appeared before the usual onset of disease. Patient had strong positive family history of HD and on genetic analysis test; there was a higher number (60) of CAG repeats suggestive of earlier onset of disease. The age of onset inversely correlated with the size of the triplet repeat expansion.[3] The progression of HD is inexorable and usually leads to death within 15 to 20 years of presentation in patients who eventually become immobile and severely demented.[4] However, in future treatment with transplantation of fetal neuronal material to replace the degenerated neurons and cell engineered to secrete neurotrophic factors in HD are emerging to ameliorate the condition but replication of results in human needs further research.[5]

The affective disorders may be present 20 years prior to the onset of chorea and dementia in HD. The prevalence of Major affective disorder is found in 41% of patients with HD, 32% being depressive and 9% bipolar.[2] Findings show that the frequency of suicidal ideation doubled from 9.1% in at-risk persons with a normal neurological examination to 19.8% in at-risk persons with soft neurological signs and increased to 23.5% in persons with “possible HD.” In persons with a diagnosis of HD, 16.7–21.6% had suicidal ideation,[6] 5.7% of deaths among affected persons resulted from suicide and 27.6% of patients attempted suicide at least once.[7]

This case shows that patients of HD can present with symptoms of either depression or mania which can further increase the risk of suicide in these patients. Psychosis is not uncommon in bipolar disorder and in case of HD with chorea, the treatment with haloperidol to ameliorate choreiform movement is dependent on the serum haloperidol concentration.[8] Hence cases such as ours emphasize the need for the psychiatrists to be aware of the psychological symptoms and the suicidal risk associated in patients presenting with organic brain disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paulsen JS, Ready RE, Hamilton JM, Mega MS, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric aspects of Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:310–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.3.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folstein S, Abbott MH, Chase GA, Jensen BA, Folstein MF. The association of affective disorder with Huntington's disease in a case series and in families. Psychol Med. 1983;13:537–42. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700047966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenblatt A. Neuropsychiatry of Huntington's disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9:191–7. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.2/arosenblatt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovestone S. Alzheimer's disease and other dementias (including Pseudodementias) In: David AS, Fleminger S, Kopelman MD, Lovestone S, Mellers JD, editors. Lishma's Organic Psychiatry: A Textbook of Neuropsychiatry. 4th ed. London: Wiley Blackwell Publishing; 2009. pp. 576–84. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman TB, Sanberg PR, Isacson O. Development of the human striatum: Implications for fetal striatal transplantation in the treatment of Huntington's disease. Cell Transplant. 1995;4:539–45. doi: 10.1177/096368979500400604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulsen JS, Hoth KF, Nehl C, Stierman L. Critical periods of suicide risk in Huntington's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:725–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrer LA. Suicide and attempted suicide in Huntington disease: Implications for preclinical testing of persons at risk. Am J Med Genet. 1986;24:305–11. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320240211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr AN, Fischer JH, Koller WC, Spunt AL, Singhal A. Serum haloperidol concentration and choreiform movements in Huntington's disease. Neurology. 1988;38:84–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]