Abstract

Background:

Of various spiritual care methods, mindfulness meditation has found consistent application in clinical intervention and research. “Listening presence,” a chaplain's model of mindfulness and its trans-personal application in spiritual care is least understood and studied.

Aim:

The aim was to develop a conceptualized understanding of chaplain's spiritual care process based on neuro-physiological principles of mindfulness and interpersonal empathy.

Materials and Methods:

Current understandings on neuro-physiological mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) and interpersonal empathy such as theory of mind and mirror neuron system are used to build a theoretical framework for chaplain's spiritual care process. Practical application of this theoretical model is illustrated using a carefully recorded clinical interaction, in verbatim, between chaplain and his patient. Qualitative findings from this verbatim are systematically analyzed using neuro-physiological principles.

Results and Discussion:

Chaplain's deep listening skills to experience patient's pain and suffering, awareness of his emotions/memories triggered by patient's story and ability to set aside personal emotions, and judgmental thoughts formed intra-personal mindfulness. Chaplain's insights on and ability to remain mindfully aware of possible emotions/thoughts in the patient, and facilitating patient to return and re-return to become aware of internal emotions/thoughts helps the patient develop own intra-personal mindfulness leading to self-healing. This form of care involving chaplain's mindfulness of emotions/thoughts of another individual, that is, patient, may be conceptualized as trans-personal model of MBI.

Conclusion:

Chaplain's approach may be a legitimate form of psychological therapy that includes inter and intra-personal mindfulness. Neuro-physiological mechanisms of empathy that underlie Chaplain's spiritual care process may establish it as an evidence-based clinical method of care.

Keywords: Chaplain, empathy, healing, mindfulness, mirror neuron, religion, spiritual

INTRODUCTION

Spiritual care is reportedly provided in various forms such as prayers by religious/spiritual (r/s) care providers in hospital settings,[1,2] faith healers at religious places of worship[3,4] or as part of traditional, complementary and alternative medical (TCAM) treatments.[5,6] Over the last several decades, in United States and few other developed nations, hospital-based r/s care services had evolved into a professional department of chaplaincy/pastoral care.[7,8] The spiritual care providers from this department are called as chaplains. While the rest of the world may still be unaware of this specialized profession, pastoral care providers/chaplains are graduates, with masters’ degree in theology, and they undergo rigorous, 1-year long, nationally accredited training[9,10] in providing spiritual care to hospitalized patients. This training and education, called as Chaplain-Residency and clinical pastoral education (CPE), helps a chaplain to provide spiritual care to pluralistic patient population without the necessity of prayer/religious rituals and/or other techniques of TCAM.

Research studies on chaplaincy have focused on understanding their role in health care,[11,12] their service utilization,[13,14,15] as well as the clinical outcomes of their services,[16,17] but there are no studies describing their spiritual care processes and/or possible scientific mechanisms underlying this approach. This paper presents a typical clinical interaction between a chaplain and his patient. It focuses on understanding possible mechanisms underlying chaplain's spiritual care while describing the care process for informed understanding of chaplaincy by other health care professionals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The author's experiential understanding of the theory and practice of chaplain's spiritual care process is described, followed by literature review on the current understandings of neuro-physiological mechanisms involved in mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) and interpersonal empathy with an attempt to build a theoretical framework for the chaplain's model of care. A chaplain-patient clinical interaction is presented in verbatim demonstrating a typical spiritual care process in chaplaincy, and it is used for a qualitative basis in this paper. The literature review is used to explain/analyze how what happens in the verbatim may be explained by neural mechanisms. With examples of empathetic interactions from the verbatim and the neuro-physiological theories demonstrating one another, this paper attempts to conceptualize chaplain's care as a trans-personal model of MBI.

Introduction to chaplain's model of spiritual care

Described as “Listening Presence,” the chaplain's model of spiritual care is described by Wolfelt[18] in his single author textbook/guide for chaplains-in-training and this is the model of care adapted effectively by CPE-trained chaplains, however not grounded in any scientific theory. The steps in this model of care includes, a chaplain (1) actively listening to emotional pain and struggles in a patients’ story (2) becoming aware of how the patient's story is triggering emotional memories within, (3) remaining mindfully aware but without “suffering” from them (4) avoiding cognitive calculations or judgments about patient's behavior or life's choices, (5) returning focus to empathize with patient's pain/struggles using verbal and nonverbal communication, (6) facilitating patient to share painful emotions/stories, which increases their intra-personal awareness (7) while resisting own urge to rush the patient out of their pain and suffering, that is, avoids making “treatment plans” for the patient. Thus, with its key ingredients of empathy and mindfulness of patients’ emotional state, this model of “Listening Presence” has close resemblance to the MBI;[19] which in the context of a dyadic relationship such as chaplain-patient interaction takes a trans-personal/transcendental form of mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation and its intervention in clinical care has been the most widely studied model of spiritual care;[20,21] elaborate understandings on the neuro-physiological mechanisms of this model would serve to build our theoretical frame-work of chaplaincy process.

Literature review on mindfulness based intervention and interpersonal empathy

Mindfulness meditation and its application in medicine

Mindfulness is a meditative art of being in a state of non-judgmental, compassionate and purposeful awareness of thoughts and feelings that arise in the present moment within an individual.[22,23] Because of its positive effects on well-being, in the last few decades it has been increasingly incorporated to augment existing cognitive and behavioral therapies.[19,20,21] These MBI typically start as therapist guided meditation sessions which progress into independent patient practice.[21] The aim of MBI is to enhance “metacognitive” awareness of negative self-depreciative, automatic, ruminative thoughts and feelings as mere “mental events rather than aspects of or direct reflections of truth.”[24] In the parlance of chaplain/pastoral education “metacognition” is described in terms of “inner-dialogue”[25] which enhances exploration of one's own experiences in newer ways[26] and strengthens their responsibility for their feelings, values and perceptions[25] allowing the individuals to become compassionate witnesses to their own painful experiences ultimately leading to self-healing.[27]

Neuro-physiological mechanisms of emotional pain, suffering, mindfulness and healing

Physiologically, the hippocampus and amygdala-parts of the limbic brain-work together to detect emotional threats from current events[28] based on past memory/historical experiences; of the two, amygdala is the “alarm/freight-raiser,”[29] sending impulses to all parts of the brain for effective flight/fight action. Pathologically, hyper-functioning of amygdalae causes excessive ruminations of past pain and/or worries about the future which characterizes suffering and depression[30] and other psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, panic or paranoia. On the other hand, cortical circuits arising from hippocampus, cingulate, prefrontal and temporo-parietal areas, involved in learning and memory processing, help in modulating cortical arousal and its responses to emotional stimuli.[31,32] Insula - yet another cortical region - is reported to be responsible for self-awareness of internal, both nonconscious physical and emotional sensations, as well as the awareness of conscious motivational and social, feelings.[33,34,35] Mindfulness training, as evidenced by neuroimaging studies, increases thickness of the said cortical areas to enhance their attention monitoring systems and improve conscious awareness of the internal emotional sensations. It effectively modulates emotional arousal and cultivate compassion while down-regulating emotional centers such as amygdala.[31,36,37,38,39] Mindfulness meditation also trains the prefrontal cortex to promote stable recruitment of non-conceptual sensory pathways-an alternative to conventional cognitive reappraisal strategies-which in turn reduces habitual negative self-evaluative processing of the brain, and consequentially leads to healing.[20,31] Vago and Silbersweig[40] suggest that mindfulness training enhances the cortical control system by integrating various parts of the frontal, parietal and even cerebellar areas of the brain responsible for meta-monitoring necessary for self-awareness and self-regulation of emotions.

Though MBI has been reported to be very effective in various medical and psychiatric disorders, clinicians and researchers conclude that it is difficult to apply in acutely symptomatic patients.[41,42] However, chaplains do visit even acutely ill-patients (physically and mentally), to provide an empathetic presence, which helps in self-regulation of emotions within those symptomatic patients. Therefore, understanding the chaplains’ trans-personal model of MBI may become more important even for acute-setting patient care.

Theories and neurological mechanisms of interpersonal empathy

Based on our emotional experiences, when we intuitively conceptualize the existence of a non-observable entity such as a “mind” then we are said to have a theory of mind (ToM). Further, this ToM helps us deduce that other individuals also have a mind, and this knowledge helps us to understand the emotions and feelings of others.[43,44] Empathy is described, by neuroscience researchers, as having a capacity to experience the feelings of others within oneself as if those emotions are one's own;[45,46] Spiritual care providers[25] also describe “empathy” in the same way and hence the mechanism underlying interpersonal empathy, as understood by neuroscientists may be acceptable to spiritual care professionals as well. Neuroscientific research on ToM,[47] and “Simulation theory”[48,49] helps us understand the mechanism of interpersonal empathy. This empathetic process is said to be processed by a network of neurons that are active during an individual's own cognitive and motor behavior as well as when that individual sits merely observing the behavior of others;[50,51] this set of neurons is called as mirror neuron system (MNS). Further studies revealed that these mirror neurons not only respond to the observed physical activities of other individuals but also involuntarily resonates/mirrors the feelings as well as being responsible for understanding the intentions and motivations behind the actions of others thereby establishing empathetic connection between two individuals.[47,52,53,54,55]

Ramachandran and Brang[56] reported that this resonance comes from a dynamic equilibrium between individual brains; other researchers suggest that resonance is due to an individual's involuntary and unconscious ability to develop theories (ToM) about what another person is thinking.[45] Oberman et al.[57] elaborate that MNS in an individual functions by matching the external environmental perceptions with preexisting representation present within their internal sensory-motor cortex of the brain. Researchers[58,59] suggest an interplay between the ToM and MNS mechanisms to produce the emotional contagion[60,61] and empathetic understanding of others while invoking self-empathy within the individual recipients in the relationship,[62,63] and in case of a patient-recipient this invoked self-empathy helps in producing desirable clinical benefits. Judging other persons weaknesses, wisdom, intelligence, and intentions is a major stone-wall that prevents interpersonal empathy; “suspending judgment” is another major process in interpersonal empathy,[25] which, again, is a function based on metacognition and insular awareness.[20,31,40]

Similar to the analogy of a “waterfall versus water-in-the-bucket,”[64] for better understanding, neuro-physiological mechanisms reviewed above are tied to various real-life examples of mindfulness, and inter-personal empathy noted in the verbatim of chaplain-patient clinical interaction described below.

Study setting and methodology

This clinical encounter occurred on the medical floor of a tertiary care medical center under the Franciscan Health System (FHS), a Catholic institution in Washington, USA. The primary encounter that is reported in this paper was about 45 min long, there were couple of brief, 15 min, follow-up visits, the highlights of one of them is included in this paper/table. The patient is an elderly Caucasian, American, devout Christian, female patient with a history of recurrent pneumonia, under investigation for a possible lung cancer, currently her symptoms were in remission. The patient was also diagnosed with “mild depression.” As described elsewhere in this paper, so as to provide a nonjudgmental presence this chaplain avoided knowing patient's diagnoses prior to visiting with the patient. Hospital guidelines were followed to take care of issues related to patient privacy and informed consent.

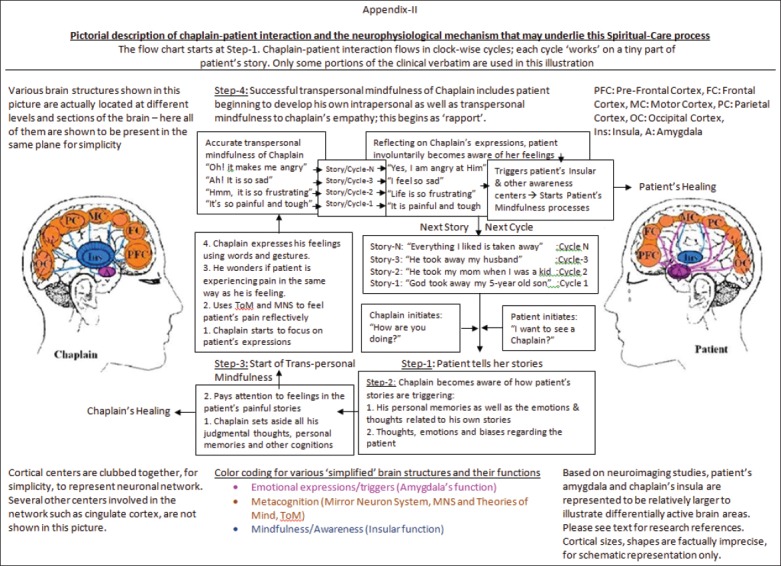

The spiritual care provider/chaplain in this case is a psychiatrist by profession and he could draw on all his knowledge in neuropsychological mechanisms of interpersonal empathy as well as psychotherapeutic skills obtained from past professional training and experience. While psychotherapeutic skills enables the spiritual care process, intellectual activities such as diagnosis and treatment plans, that are essential part of psychiatric care are in fact judgmental behavior and hence a hindrance in establishing and maintaining the ToM based-empathic, healing-loop between the provider and the patient [Figure 1]. Spiritual care residency training provides a chaplain the skill in staying with the feelings, avoiding all distractions including diagnosing and/or planning the next steps in treating the patient that are normal processes of psychiatric assessment and care. Nonetheless, this author believes that the desirable clinical outcome in this case was due to his past training in psychiatry and psychotherapy along with regular practice of mindfulness meditation that helped him in strengthening listening skills of chaplaincy. Though the patient was unaware of this chaplain's psychiatric/medical background, her appreciative comment [Appendix 1, P32] would make the reader wonder as to what qualifies a person to be called as a physician, in the eyes of a patient.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the intra and transpersonal model of mindfulness in a chaplainæs spiritual care process

The whole chaplain-patient interaction was recollected, as much as possible out of memory, recorded in verbatim [Appendix 1] by the chaplain, immediately after exiting the patient's room so as to maintain the accuracy of the qualitative data. The encounter is traditionally organized into three columns, for CPE studies: (1) Patient-chaplain interaction, verbatim, (2) objective observations of patient and self/chaplain's behavior, and clinical environment and (3) subjective description of chaplain's own thoughts and feelings. Further, the qualitative clinical data from the verbatim is systematically organized and studied under two separate, chaplain and patient phases, which actually occurred concurrently as seen in the schematic presentation [Figure 1].

Analyzing the qualitative data [Appendix 1]

Chaplain's phase

Chaplain enters the patient's room mindfully aware of his emotions/curious feelings. Mindfulness is known to prepare an individual to remain aware, be receptive to newer and ever changing emotions,[22,23] which helped chaplain remain calmly aware of his emotions triggered by the clinical situation (S2, S8) as well as remain dynamically present to patient's ever changing momentary emotions and fleeting thoughts (P4). Being mindful also helped chaplain to become aware of how patient's stories are triggering his emotions and memories (S15). Mindfulness improves individual's skills to listen deeply to understand the patient's emotions and thoughts in a better way;[63] with his deep listening skills, the chaplain, reflectively and vicariously feels and understands the patient's pain and suffering accurately (P16, C11, P17).

Using ToM,[43,44] the mindful chaplain became fully attentive to patient's facial expressions, body language and emotional stories and connected those dots with his own internal emotions, thoughts and was thus able to match the patient's emotional struggles with similar ones of his own (S2, S15). It helped the chaplain to empathize with patient's pain/struggles.[47] As described elsewhere, neurologists describe this process in terms of ToM[47] or simulation theory[48,49] which also involves MNS networks of empathy. Chaplain's mindfulness also includes metacognitive abilities that help in setting aside judgmental thoughts and avoiding advice. Conventional wisdom of helping such a patient as in this verbatim would include statements such as “eat something, you need some energy” (S8), or asking “what happened to your husband, how did he die?” or “don’t worry about your cat, your friends will take good care of it” (C8, C10 not shown in truncated table). Statements such as these would belie a chaplain's ability to stay mindful of patients’ painful emotions. They demonstrate his own need and/or internal urge to move quickly to a more comfortable place of cognitive-solution seeking role. While, staying with the feelings that underlie patient's statements demonstrate chaplain's empathy to patient's painful emotions as well as to her maladaptive cognitions. Patient starts to model the chaplain in staying connected with her own emotions and that in turn helps the patient to self-empathize with her own painful feelings. As a provider, chaplain returns and re-returns his focus to be mindful of patient's pain and sufferings; sharing only his empathetic feelings of patient's pain and suffering and avoids cognitive derivations of those feelings (C11). He facilitates the patient to share more of her stories, using carefully worded open-ended and self-reflective statements expressing/labeling the feelings (C11).

Patient phase

Initiated by the chaplain (C3, 4), patient shares her painful stories and becomes unconsciously aware of her emotions/thoughts (P4, P8) and further, observing the chaplain's emotional expressions, she reflectively and consciously starts to feel her own emotions. Patient's intra-personal mindfulness improves further as she poses a question, probably rhetorically, when she said, “How does it feel?” (P11). Also likely, she was hesitant/afraid to even look at her own painful emotions; then probably encouraged by the chaplain's continued attention to her painful/fearful emotions, she confronts them herself (P16, 17). With each of patient's story chaplain responds with expressions labeling those painful emotions which helped the patient to identify reflectively and become aware of her own feelings (C11).

Needless to say, even this patient was equipped with her own ToM. However because of the intensity of emotional preoccupation she was unmindful of her own emotions. Initially the patient did not care for anything outside of her self-consuming thoughts, she had poor eye contact (O2) and she “would not care whether the chaplain was a Catholic or Protestant or a Rabbi” (P2) but eventually comes out of her preoccupations to be able to focus on the external by inquiring about the chaplain's where-about and faith tradition. She breaks off from her negative automatic thoughts and starts to inspect and corrects her own thoughts and speech (P19, P20a, b); this may be chaplain-induced meta-cognition within the patient or rekindling of her ToM. Patient returns and re-returns to feel her emotions by retelling her painful stories in greater depth and details (P16), indicating her feelings of comfort and security of an empathetic and nonjudgmental chaplain; clearer understanding of self and others[65] rapport building are described to be functions of MNS.[65,66] Development of rapport indicates initiation of patient's trans-personal mindfulness which becomes obvious when she starts to reflect on the intentions of the empathizing chaplain (P18). While ToM is known to help us understand the emotional intentions behind the behavior of others, MNS provides us the neural basis for that understanding.[67] Patient comes to feel and believe that the chaplain is able to empathize with her painful emotions without judging her. Empathetic behavior can be automatically grasped by the observer through MNS mechanisms;[50,51,54,55] chaplain's behavior becomes involuntarily and reflectively mirrored by patient's brain[48,49] leading her to develop improved awareness (P19-20, S34) of her painful emotions and automatic judgmental/negative thoughts. As the patient remained aware of them without feeling the need to move away, reflecting the chaplain's behavior, intuitively she understood that those thoughts and emotions are mere works of her mental activities and not actual truths[22] thus leading to self-empathy/compassion and eventual healing.[68,69] Improved clinical outcome was evident from her improved eye contact, reversal of sad, angry mood (O34), becoming cheerful, relaxed (O36) making positive statements, and attending to her nutritional needs (P25, 26-not shown in table). Her cheerful mood continued into the follow-up visit, the next day when she thanked the chaplain profusely for the previous night visit saying that she “woke up (in the morning) with feet above the grass” and had a good breakfast. Patient's friend had also acknowledged the improved mood of the patient (P29, O52- not shown in table).

DISCUSSION

Improved awareness of emotions and metacognitive abilities indicates activation of patient's insular[33,34,35] and cortical functions[31,36,37,38,39] respectively, which subdue amygdala leading to reduced emotional reactivity[29] resulting in self-healing evidenced by the significantly desirable clinical outcomes. Spiritual care process of a chaplain involving his mindful empathetic presence to another individual's emotional pain and suffering may be understood as trans-personal mindfulness mediated through ToM. The existence of such a process may be empirically evident from the significantly desirable outcomes noted in this clinical encounter, and this argument is best supported by evidence-based, neuroimaging studies validating the existence of provider-patient empathic-loop by “lighting-up” interpersonal cortico-cortical connections that are described by MNS.[70]

Though this chaplain's intervention resulted in significantly desirable clinical outcome, some of his subtle subconscious thoughts (S15, S20) may have influenced the way the interaction took shape; there can be several educational pieces from this verbatim for chaplaincy but they are not the focus of this paper. As Rev Dr John Switon[64] suggests, in our attempt to study spiritual care process from a scientific perspective, we had to deconstruct the “beautiful waterfall” of a chaplain-patient empathic interaction into two separate, chaplain and patient, phases as well as into two, intra and trans-personal, modes of mindfulness. While such breakdown is necessary for better understanding of various components of this complex process of chaplaincy, it also robs the process of its various other unmeasurable qualitative aspects. With mindfulness processes occurring in both chaplain and the patient, healing process may also be occurring in both of them, and no doubt, it is a common belief among chaplains that spiritual healing is never provided but received by both individuals in a dyad. Chaplain's mindfulness helped him to instantly and reflexively feel patient's painful emotions and stay with it leading to the desirable clinical outcome observed at the end of the visit. The clinical benefits could be mediated through ToM and MNS mechanisms leading to the cortico-cortical connections[55] and the dynamic equilibrium[56] between chaplain and patient's brain. The chaplain, being a psychiatrist, was able to draw on his knowledge of neuro-psychological processes involved in provider-patient interaction. Training in mindfulness meditation further helped him to remain in the ever-changing present moment during the clinical visit. Thus, this author believes that, training in both psychiatry/clinical-psychology and mindfulness-based methods of care are essential for an effective chaplaincy.

The clinical outcome may also be dependent on various provider variables such as a chaplain's personal practice of mindfulness meditation and unmeasured patient variables. Some of the patient variables that may have contributed to the outcome would be milder symptoms and the wisdom of an elderly person who could touch-base with her innate strengths in mindfulness re-inspired by the chaplain; one would imagine that it will be highly impossible to regain one's strengths of mindfulness within one session. The clinical outcome, even though very positive, may also be a fleeting change in patient's behavior.

Implications of this study

This paper is first of its kind to illustrate a chaplain's spiritual care process of “listening presence” in terms of mindfulness, and with this we attempt to bridge the chaplain's clinical care model with that of MBI programs. Further, by conceptualizing a trans-personal form of mindfulness, which may be applicable in acute care settings, we can establish chaplaincy as a powerful model of spiritual care. Defining chaplaincy as an MBI model would attract clinicians and researchers towards chaplaincy, deservedly, with the same vigor they bestow on MBI programs. A chaplain's care may be viewed as a forerunner to introducing patients, naïve, to mindfulness-based techniques. Chaplains being recognized as experts in spiritual care[71] may benefit by identifying the key element of mindfulness in their model of care and understanding neurobiological processes involved in it. Illustrating neurological processes underlying chaplain's spiritual care will help in bridging chaplaincy with neurosciences and establish it as a scientific clinical subject. Training and practice of meditation is reported to activate brain circuits linked with empathy and ToM for an enhanced and effective response to emotional stimuli,[72] promoting mindfulness in psychotherapists-in-training had significantly improved the desirable therapeutic course and outcome among their patients.[73] Clinical outcomes of chaplains’ spiritual care may as well improve by promoting mindfulness in chaplaincy training. While MBI programs may adapt the chaplaincy model to care for their actively symptomatic patients, clinical chaplains may consider incorporating MBI program's patient training module[74,75] for patients’ continued self-care upon discharge and empowering them as active participants in their own healing process and preventing relapse.[76]

Limitations

Spirituality is not quantifiable, and manifestations of spiritual care process are often unique, findings are qualitative in nature and are nongeneralizable. Other limitations include nonideal collection of qualitative data; the chaplain-patient interaction could not be recorded electronically due to institutional policy of FHS and more importantly any attempt to record such a sensitive and intimate spiritual care conversation will interfere with rapport-building, care process, and clinical outcome; readers may be informed that even taking physical notes while visiting with a patient is discouraged in chaplaincy practice. Though the whole verbatim was recorded immediately after exiting the patient's room there may be few inadvertent omissions by chaplain.

CONCLUSION

To develop into a scientific, clinical discipline, Spiritual care providers have to demonstrate evidence-based interventions and outcomes. Understanding the spiritual care process using neurological principles may be an inevitable step in further development of Spiritual Care/chaplaincy as a clinical subject. Notwithstanding the limitations, further studies are possible and needed to strengthen our argument.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am deeply indebted to my CPE supervisor, Dr. Rev. Garrett Starmer, for his patient guidance and his Socratic-teaching skills which helped me understand the spiritual care process in an experiential way. Special thanks goes to my colleagues in the CPE residency group for their continued critical as well as validating feedback that helped me understand my strengths and growing edges. I would like to thank the entire faculty especially, Chaplains Kathy Olson, Paula, and Jane Profont at the Spiritual Care Department of Franciscan Health System group for compassionate and way-side lessons in spiritual care. I greatly appreciate Ch. Judy Klontz, Ch. Glori Schneider (my chaplain supervisors), Dr. Kevin Flannelly, (Chaplain and editor of JHCC), Dr. Pratima Murthy (Professor of Psychiatry, NIMHANS) and Dr. David Vago (Instructor, Functional Neuroimaging lab, Harvard Medical School) for their valuable inputs.

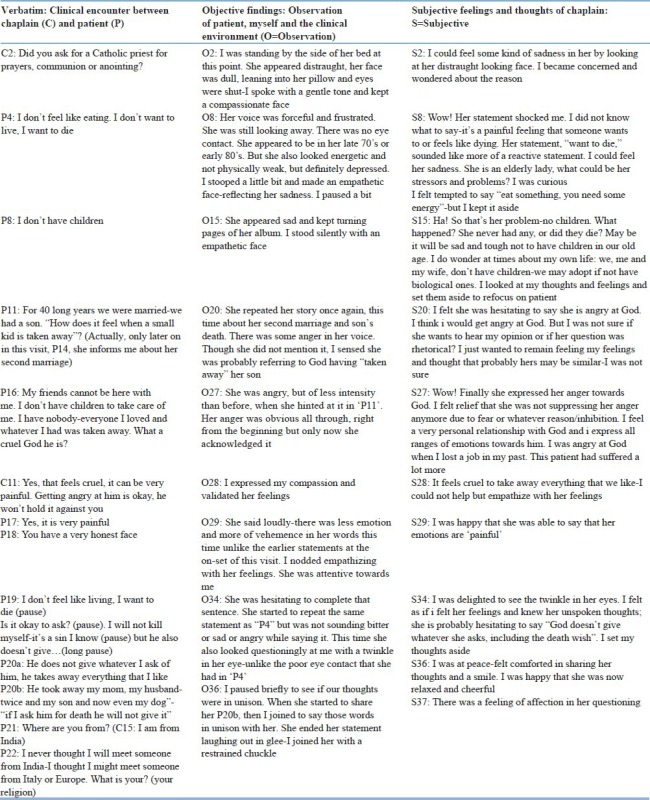

Following is the verbatim (qualitative data) of clinical encounter between the chaplain (spiritual care provider) and patient

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Dein S, Pargament K. On not praying for the return of an amputated limb: Conserving a relationship with God as the primary function of prayer. Bull Menninger Clin. 2012;76:235–59. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2012.76.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olver IN, Dutney A. A randomized, blinded study of the impact of intercessory prayer on spiritual well-being in patients with cancer. Altern Ther Health Med. 2012;18:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra N, Nagpal SS, Chadda RK, Sood M. Help-seeking behavior of patients with mental health problems visiting a tertiary care center in north India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:234–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raguram R, Venkateswaran A, Ramakrishna J, Weiss MG. Traditional community resources for mental health: A report of temple healing from India. BMJ. 2002;325:38–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7354.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Arye E, Schiff E, Vintal H, Agour O, Preis L, Steiner M. Integrating complementary medicine and supportive care: Patients’ perspectives toward complementary medicine and spirituality. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:824–31. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longacre M, Silver-Highfield E, Lama P, Grodin M. Complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of refugees and survivors of torture: A review and proposal for action. Torture. 2012;22:38–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart CW, Div M. Present at the creation: The clinical pastoral movement and the origins of the dialogue between religion and psychiatry. J Relig Health. 2010;49:536–46. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jernigan HL. Clinical pastoral education: Reflections on the past and future of a movement. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2002;56:377–92. doi: 10.1177/154230500205600407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene AE, VandeCreek L. The ACPE supervisory education process: An historical perspective. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2013;67:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford T, Tartaglia A. The development, status, and future of healthcare chaplaincy. South Med J. 2006;99:675–9. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000220893.37354.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cramer EM, Tenzek KE. The chaplain profession from the employer perspective: An analysis of hospice chaplain job advertisements. J Health Care Chaplain. 2012;18:133–50. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2012.720548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S. Pastoral identity constructed in care-giving relationships. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2012;66:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossoehme DH, Cotton S, McPhail G. Use and sanctification of complementary and alternative medicine by parents of children with cystic fibrosis. J Health Care Chaplain. 2013;19:22–32. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2013.761007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flannelly KJ, Emanuel LL, Handzo GF, Galek K, Silton NR, Carlson M. A national study of chaplaincy services and end-of-life outcomes. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Provenzale D, Griffin JM, Phelan S, Nieuwsma JA, et al. Utilization of hospital-based chaplain services among newly diagnosed male Veterans Affairs colorectal cancer patients. J Relig Health. 2014;53:498–510. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossoehme DH, Ragsdale JR, Cotton S, Meyers MA, Clancy JP, Seid M, et al. Using spirituality after an adult CF diagnosis: Cognitive reframing and adherence motivation. J Health Care Chaplain. 2012;18:110–20. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2012.720544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams JA, Meltzer D, Arora V, Chung G, Curlin FA. Attention to inpatients’ religious and spiritual concerns: Predictors and association with patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1265–71. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1781-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfelt AD. Companioning the Bereaved. A Soulful Guide for Counselors and Caregivers Publisher, Companion Press. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabat-Zinn J. New York: Dell Publishing; 1990. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sipe WE, Eisendrath SJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Theory and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57:63–9. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal ZV, Williams JM, Teasdale JD. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse; pp. 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1350–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams JM, Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Kabat-Zinn J. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. The Mindful Way through Depression: Treeing Yourself from Chronic Unhappiness. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, Segal ZV. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: Empirical evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:275–87. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Underwood RL. Empathy and Confrontation in Pastoral Care: Wipf and Stock Publishers. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Hurk PA, Wingens T, Giommi F, Barendregt HP, Speckens AE, van Schie HT. On the relationship between the practice of mindfulness meditation and personality-An exploratory analysis of the mediating role of mindfulness skills. Mindfulness (N Y) 2011;2:194–200. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ott MJ. Mindfulness meditation: A path of transformation and healing. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2004;42:22–9. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20040701-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bishop SJ. Neural mechanisms underlying selective attention to threat. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:141–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasia-Filho AA, Londero RG, Achaval M. Functional activities of the amygdala: An overview. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25:14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayberg HS. Modulating dysfunctional limbic-cortical circuits in depression: Towards development of brain-based algorithms for diagnosis and optimised treatment. Br Med Bull. 2003;65:193–207. doi: 10.1093/bmb/65.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, et al. Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res. 2011;191:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fichtenholtz HM, Dean HL, Dillon DG, Yamasaki H, McCarthy G, LaBar KS. Emotion-attention network interactions during a visual oddball task. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;20:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig AD. How do you feel – now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:189–95. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrer C, Franck N, Georgieff N, Frith CD, Decety J, Jeannerod M. Modulating the experience of agency: A positron emission tomography study. Neuroimage. 2003;18:324–33. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, Gray JR, Greve DN, Treadway MT, et al. Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1893–7. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Way BM, Creswell JD, Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Dispositional mindfulness and depressive symptomatology: Correlations with limbic and self-referential neural activity during rest. Emotion. 2010;10:12–24. doi: 10.1037/a0018312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10:83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creswell JD, Way BM, Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:560–5. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f6171f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vago DR, Silbersweig DA. Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:296. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crane C, Williams JM. Factors Associated with attrition from mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with a history of suicidal depression. Mindfulness (N Y) 2010;1:10–20. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edenfield TM, Saeed SA. An update on mindfulness meditation as a self-help treatment for anxiety and depression. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2012;5:131–41. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S34937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. Affiliation, empathy, and the origins of theory of mind. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(Suppl 2):10349–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301223110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci. 1978;1:515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCormick LM, Brumm MC, Beadle JN, Paradiso S, Yamada T, Andreasen N. Mirror neuron function, psychosis, and empathy in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;201:233–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Preston SD, de Waal FB. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25:1–20. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Völlm BA, Taylor AN, Richardson P, Corcoran R, Stirling J, McKie S, et al. Neuronal correlates of theory of mind and empathy: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in a nonverbal task. Neuroimage. 2006;1(29):90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gallese V. Before and below ‘theory of mind’: Embodied simulation and the neural correlates of social cognition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:659–69. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallese V, Goldman A. Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mind-reading. Trends Cogn Sci. 1998;2:493–501. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:169–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keysers C, Gazzola V. Towards a unifying neural theory of social cognition. Prog Brain Res. 2006;156:379–401. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mainieri AG, Heim S, Straube B, Binkofski F, Kircher T. Differential role of the mentalizing and the mirror neuron system in the imitation of communicative gestures. Neuroimage. 2013;81:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liew SL, Han S, Aziz-Zadeh L. Familiarity modulates mirror neuron and mentalizing regions during intention understanding. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:1986–97. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gallese V, Sinigaglia C. What is so special about embodied simulation? Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:512–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koch G, Versace V, Bonnì S, Lupo F, Lo Gerfo E, Oliveri M, et al. Resonance of cortico-cortical connections of the motor system with the observation of goal directed grasping movements. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:3513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramachandran VS, Brang D. Sensations evoked in patients with amputation from watching an individual whose corresponding intact limb is being touched. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1281–4. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oberman LM, Pineda JA, Ramachandran VS. The human mirror neuron system: A link between action observation and social skills. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:62–6. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hooker CI, Verosky SC, Germine LT, Knight RT, D’Esposito M. Neural activity during social signal perception correlates with self-reported empathy. Brain Res. 2010;1308:100–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schulte-Rüther M, Markowitsch HJ, Fink GR, Piefke M. Mirror neuron and theory of mind mechanisms involved in face-to-face interactions: A functional magnetic resonance imaging approach to empathy. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:1354–72. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.8.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manera V, Grandi E, Colle L. Susceptibility to emotional contagion for negative emotions improves detection of smile authenticity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:6. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wild B, Erb M, Bartels M. Are emotions contagious? Evoked emotions while viewing emotionally expressive faces: Quality, quantity, time course and gender differences. Psychiatry Res. 2001;102:109–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haker H, Schimansky J, Rössler W. Sociophysiology: Basic processes of empathy. Neuropsychiatr. 2010;24:151–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams JH. Self-other relations in social development and autism: Multiple roles for mirror neurons and other brain bases. Autism Res. 2008;1:73–90. doi: 10.1002/aur.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rev, John Switon. Rediscovering mystery and wonder: Toward a narrative-based perspective on chaplaincy. J Health Care Chaplain. 2002;13:223–36. doi: 10.1300/J080v13n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monshat K, Khong B, Hassed C, Vella-Brodrick D, Norrish J, Burns J, Herrman H. “A conscious control over life and my emotions:” mindfulness practice and healthy young people. A qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):572–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.008. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rossi EL, Rossi KL. The neuroscience of observing consciousness and mirror neurons in therapeutic hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn. 2006;48:263–78. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2006.10401533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corradini A, Antonietti A. Mirror neurons and their function in cognitively understood empathy. Conscious Cogn. 2013;22:1152–61. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hall CW, Row KA, Wuensch KL, Godley KR. The role of self-compassion in physical and psychological well-being. J Psychol. 2013;147:311–23. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.693138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Germer CK, Neff KD. Self-compassion in clinical practice. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:856–67. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Braadbaart L, de Grauw H, Perrett DI, Waiter GD, Williams JH. The shared neural basis of empathy and facial imitation accuracy. Neuroimage. 2014;84:367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):49–55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lutz A, Brefczynski-Lewis J, Johnstone T, Davidson RJ. Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grepmair L, Mitterlehner F, Loew T, Bachler E, Rother W, Nickel M. Promoting mindfulness in psychotherapists in training influences the treatment results of their patients: A randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:332–8. doi: 10.1159/000107560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8:163–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00845519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Teasdale JD, Segal Z, Williams JM. How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosenzweig S, Greeson JM, Reibel DK, Green JS, Jasser SA, Beasley D. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: Variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]