Abstract

Background:

Eating disorders (EDs) are an emerging concern in India. There are few studies comparing clinical samples in western and nonwestern settings.

Aim:

The aim was to compare females aged 16–26 years being treated for an ED in India (outpatients n = 30) and Australia (outpatients n = 30, inpatients n = 30).

Materials and Methods:

Samples were matched by age and body mass index, and had similar diagnostic profiles. Demographic information and history of eating and exercise problems were assessed. All patients completed the quality-of-life for EDs (QOL EDs) questionnaire.

Results:

Indians felt they overate and binge ate more often than Australians; frequencies of food restriction, vomiting, and laxative use were similar. Indians were less aware of ED feelings, such as, “fear of losing control over food or eating” and “being preoccupied with food, eating or their body.” Indians felt eating and exercise had less impact on their relationships and social life but more impact on their medical health. No differences were found in the global quality-of-life, body weight, eating behaviors, psychological feelings, and exercise subscores for the three groups.

Conclusion:

Indian and Australian patients are similar but may differ in preoccupation and control of their ED-related feelings.

Keywords: Australia, culture, eating disorders, India, quality-of-life

INTRODUCTION

Research indicates that the early detection of eating disorders (EDs) and early intervention are associated with a good prognosis.[1] The number of EDs in India appears to be on the rise, and more patients are presenting to doctors and clinics with ED symptoms.[2,3] Despite this, there is little published research on the eating pathology and presentation of females with EDs in India. Mammen et al.[4] conducted an ED prevalence study over 6 years using a retrospective chart design, reviewing a sample of Indian psychiatric patients. They found that 1.25% of the clinical sample was diagnosed with a form of ED based on criteria of the International Classification of Diseases Version 10.

There are a few published case studies of Indian females presenting for treatment in India with a form of ED.[5,6,7,8,9] Indian females in India with an ED may not present with signs typical of EDs reported in western clinical samples such as a fear of fatness, fear of weight gain, or body image disturbances.[8] The exception is in cases of premorbid overweight or obesity that subsequently lose a significant, unhealthy amount of weight and report a fear of fatness and body image disturbance.[7] However, along with a thinner body image ideals of Indian women, recent ED cases have described a fear of fatness and body image disturbance, in those females that are more exposed to western beauty ideals.[9]

Tareen et al.[10] studied girls with low weight who presented to psychiatric clinics in the United Kingdom, and compared the symptoms of girls of Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi ethnicity with their Caucasian counterparts. They found that these South-Asian women presented with less fat phobia, weight preoccupation, and less exercising to control weight, but with more loss of appetite. South-Asians had similar body image disturbance, perfectionism, and depressive symptoms than their Caucasian counterparts. The authors commented that a lack of “fat phobia” could suggest that South-Asians do not have a strong association of “fat” as being undesirable. It should be noted that Indians in India and those in the UK would most likely experience different pressures from their family, stressors, and levels of exposure to western ideals.

A common risk factor for the development of an ED in Indians seems to be psychosocial stressors relating to family or achievement, like feelings of failure in regards to parental expectations.[6] It may be difficult to measure this as subjects may be reluctant to disclose such information if it brings shame to the family.

The interpretation of the diagnostic criteria may be susceptible to cultural differences.[11] There is insufficient research in India at present to establish the symptoms that patients present with for the treatment and which diagnostic criteria are useful in this population.

Quality-of-life questionnaires measure health with a broader perspective than merely symptom assessment. They are usually self-reported and gauge a patient's sense of well-being. Quality-of-life for EDs (QOL EDs) has been found to be useful in the Indian population for females of different socioeconomic status (SES) and ages and has also been translated into Hindi for use in population, which may not be comfortable in communicating in English.[12] Recent use of the QOL ED in an Australian clinical sample found it to be useful in ascertaining treatment effectiveness.[13]

The aim of the study was to describe key characteristics and QOL ED samples in Indian and Australian females. Since little is known about the epidemiology of EDs in India, prevalence estimates are unable to be determined. Consequently, this study is exploratory in nature, and we are unable to hypothesize whether the prevalence of EDs will differ between the Indian and Australian samples. Others have conjectured that the traditional Indian emphasis on family or “sociocentrism” may be protective, at least for those living in India[14] and so we hypothesize that Indians with EDs will report a better quality-of-life than the Australian patients. Evidence to date is inconsistent regarding body dissatisfaction, with reports of Indians having greater dissatisfaction,[15] similar levels,[16,17] and lesser dissatisfaction[18] than Caucasians. The familial protection, in combination with less exposure to the western thinness ideal, leads us to hypothesize that Indian ED patients will have lesser body dissatisfaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Indian sample

The Indian females were outpatients at a private mental health clinic in Delhi, India. Patients ranged from 16 to 24 years, were single, postmenarcheal, nulliparous, and diagnosed with an ED; psychotic patients were excluded. Thirty consecutive cases of ED were identified. No males presented for treatment. All patients had presented within 5 years of recognizing a problem associated with controlling body weight. Patients with ED were only treated as outpatients at this hospital. Two out of 30 were Islamic, while the remaining belonged to the Hindu religion. All patients attending the clinic were from middle to upper SES.

Australian samples

Inpatients and outpatients receiving treatment in a private psychiatric clinic for their ED were included. They were aged between 16 and 26 years. Thirty inpatients and 30 outpatients were found by matching their age, body mass index (BMI), and marital status against the Indian sample.

Measures and procedure

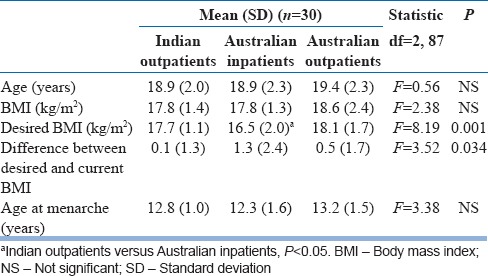

Diagnosis of an ED was made by a specialist psychiatrist as close to presentation as possible, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Version IV (DSM-IV) and all patients completed the QOL ED.[13,19] The Indian patients were given the choice between the Hindi and English versions of the QOL ED,[12] although all patients chose the English version. The QOL ED asked questions relating to the last 28 days and the last 3 months, however, all data used for analysis were for the prior 3 months, as the times for data collection could not insure a common point in treatment. For example, the first presentation for treatment and the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria require some behaviors to be present for 3 months or more. A global QOL score is calculated based on six subscores: Body weight (based on the variation from the normal range), eating behavior, ED feelings, psychological feelings, acute medical status, and effect on daily living. Two additional subscores (five questions pertaining to each subscore) relating to overeating feelings and exercise feelings were included, which were used in the development of the QOL ED, but are not included in the global QOL ED score.[19] The questions and scoring are available.[19] Current age, height, weight, age at menarche, and history of eating, weight, and exercise problems were also collected [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic information for Indian and Australian ED patients

Statistical analysis

Differences between the patient groups (Indian outpatients, Australian inpatients, and Australian outpatients) were ascertained using analysis of variances (ANOVAs) for demographics (e.g. age, BMI, and desired BMI), QOL ED scores (global and subscores), and additional scores from the exercise eating examination (overeating feelings and exercise feelings). Where a significant group difference was observed in an ANOVA, planned pairwise contrasts were conducted with the Indian sample as the reference group (i.e. Indian group versus Australian inpatients; Indian group versus Australian outpatients). In addition, where groups differed significantly on scores or subscores, a series of planned MANOVAs with Bonferroni corrections were run with the items within the scores or subscores as the dependent variable. Again, pairwise contrasts with the Indian sample as the reference, were run where the MANOVA indicated an overall group difference. All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 19.0 (www.ibm.com), and alpha was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic details

There were no significant differences in age or BMI at presentation between the Indian and Australian patient groups. Table 1 contains demographic data of Indian and Australian ED patients. Indians desired a higher BMI than Australian inpatients but lower than Australian outpatients. Dissatisfaction with body weight (difference between current and desired BMI) amongst the Indian patients was no different to that of Australians.

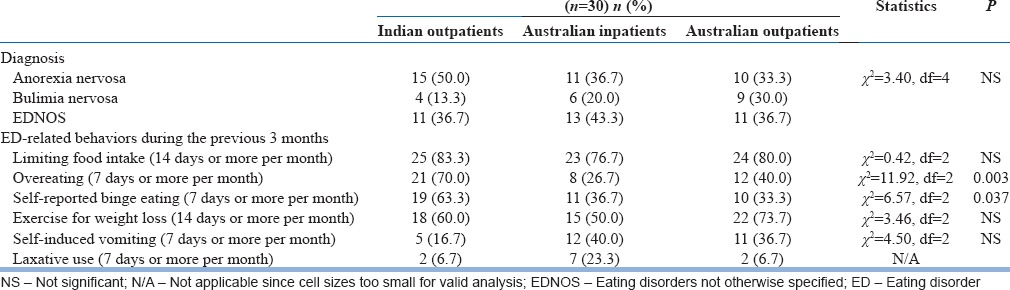

Diagnostic profiles

While AN was a more common diagnosis than BN among the whole patient population, the distribution of diagnosis did not differ significantly between the samples [Table 2]. Indians were likely to report they overate and binge ate more frequently than Australians [Table 2]. The Indian patients did not report any comorbid conditions, and none were taking medication. Among the Australian inpatients, 11 out of 30 patients recognized depression as their comorbidity and three reported anxiety. In the Australian outpatients, seven reported comorbid depression and one reported anxiety. Approximately half of the Australian patients (in both samples) were taking some form of medication for psychiatric symptoms.

Table 2.

ED diagnoses and ED-related behaviors during the previous 3 months

Quality-of-life for eating disorders

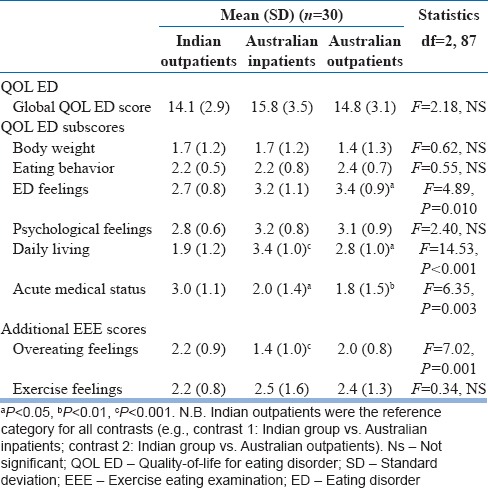

The global QOL ED and subscores for each group are listed in Table 3. The groups did not differ in the global QOL ED score and body weight, eating behaviors, psychological, and exercise subscores. The Australian groups scored higher in subscores relating to ED feelings and daily living (indicating a poorer QOL), whilst the Indian group reported a poorer QOL related to acute medical status and overeating feelings subscores compared to both Australian groups.

Table 3.

QOL ED global and subscores between Indian and Australian ED patients

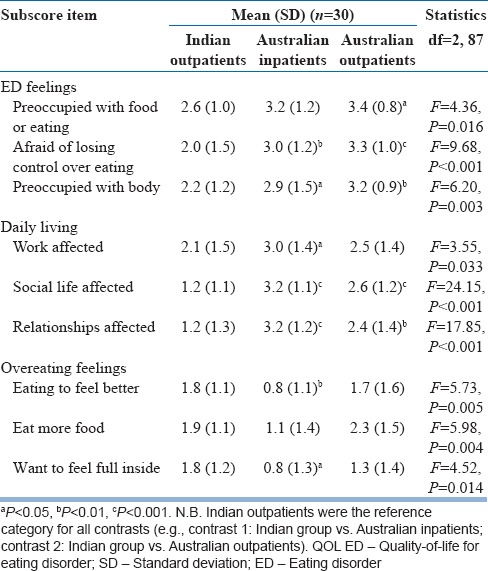

The items in the subscores that were found to be significantly different between the samples (ED feelings, daily living, overeating feelings) were further explored. These are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of significant individual items of the QOL ED subscores

DISCUSSION

This is the first published quantitative study of ED patients in India. There have been studies involving nonclinical samples, and clinical samples in western countries, but none, other than several case histories, conducted in India on a clinical sample and none comparing the same data with ED patients in a western country.

The Indian and Australian ED patients were well-matched for age and BMI and had similar ED diagnostic profiles and ED behaviors. This was confirmed by the lack of significant difference for the QOL ED eating behavior subscore between the Indian and Australian patients. Although the Australian inpatient and outpatient samples differed for body weight dissatisfaction (current BMI minus desired BMI), there was no difference between the Indian and Australian samples. The QOL ED is a more comprehensive measure of ED pathology than simply using diagnostic criteria and provides more information than eating pathology assessment tools. In addition, we believe that the QOL ED is more appropriate for use in a nonwestern culture than measures derived from western samples, since aspects of quality-of-life are more universal and comprehensible across different languages and cultures than specific diagnostic criteria.

It also reduces the importance of food- or body-related questions that are common in westernized ED specific assessment tools, for example, eating attitudes test that are not sensitive in Indian females as responses can be influenced by social or religious factors.[20]

Although there were no differences for the global QOL ED score, Indian females were less preoccupied with ED-related feelings. Fear of loss of control over eating and preoccupation with thoughts of food, eating or body weight occurred but to a significantly lesser extent for Indian patients. There have been suggestions that internal and external locus of control is a factor that deserves more recognition and further research in nonwestern samples.[21,22] We suggest that the subscore relating to ED feelings is based on questions that reflect a sense of personal control or autonomy, which was predominant in Australian females. We did not have specific measures of external or internal control, however, we suggest that Indian girls like other Asian population[21] have a strong orientation towards family values, collectivism rather than individualism and hence personal or internal control is less important to them. We also suggest that Indians in India may not have the opportunity or freedom to control food or eating, as cooking is usually done by servants in higher SES groups and the family would sit down to eat the same meal together. Indian patients reported a better quality-of-life related to their social life and relationships than Australian patients. Indians tend to be collectivistic rather than individualistic, and identify with being members of the family.[14] It is possible that Indians would not tend to isolate from others, and therefore, maintain close relationships when experiencing ED pathology, hence experiencing a better social and relationship QOL. There were no meaningful differences in the impact of eating and exercise on work for the Indian and Australian outpatients. The Australian inpatients reported a greater effect of their illness on work; however, this would not be unusual as they were waiting for admission to hospital or were in the hospital while data were collected and unable to work.

Indian patients felt their eating and exercise had more effect on their acute medical health. This could mean that Indian females tend to explain ED feelings and behaviors in medical and physical terms and are more accepting of the physical rather than psychological effects of their ED on their health or that they are protected from the psychological effects by family and externalizing their problems.[22] Alternatively, they may have been “sicker” when they presented for treatment. Similar varied explanations may occur for vomiting. In the study by Mammen et al.,[4] there were a high proportion of psychogenic vomiters (vomiting associated with other psychological disturbances and is not self-induced) in their sample of ED patients in India. Vomiting may be designated as involuntary in these population as an expression of their distress[4] or to avoid bringing shame upon themselves or their family. Other studies report a low prevalence of vomiting;[14] this may be due to the classification of vomiting into psychogenic (nonorganic cause) and vomiting with an organic cause. Self-induced vomiting for weight loss may not be understood or not acceptable.

Indians reported more days of overeating than the Australian samples. This did not translate into actual differences in behaviors according to diagnostic interviews conducted by their psychiatrist and the finding that the rates of bulimia nervosa were similar.

Our results did not suggest a lack of fat phobia in Indian girls, contrary to previous reports.[7,10] Fear of fatness and body image disturbance as cited in the ED criteria of the DSM-IV are difficult to comment on as being at and maintaining a low weight (refusal to gain weight, denial of seriousness of low weight) is frequently taken as evidence of body image disturbance and fear of fatness. This could account for the similarities in diagnoses in the Indian and Australian patients despite the differences in ED feelings. Another likely explanation, apart from differences in the interpretation of the diagnostic criteria, is the lack of questions relating to body image in the QOL ED. These questions, apart from being preoccupied with thoughts of body weight and shape, are not included in the QOL ED because they were not found to discriminate between ED and non-ED western females.[23]

In our study, all patients had reached menarche, developed the disorder postpubertally, and included patients who were diagnosed with AN, BN, and eating disorders not otherwise specified. These results differ from research published by Mammen et al.[4] suggesting that AN patients were more likely to develop their disorder postpubertally whereas patients with BN patients or “vomiters” were more likely to develop their disorder prepubertally. This should be investigated further but could reflect the definition of onset, for example, being overweight rather than disordered eating.

There are limitations in being able to assess large samples in Indian populations due to lack of presentations and hesitancy by the patient or families to seek treatment. Mental health stigma can prevent people from recognizing or admitting that EDs are serious problems. It has been suggested that Indian patients may not divulge information until they have developed a strong rapport and trusting relationship with the therapist.[8] Being full-bodied or “fat” has been desirable in India, and even though there may be a shift towards the value of being thin, the predisposing mental health beliefs could have caused patients to deny thoughts or feelings related to restricting, vomiting, and so on. As there were so few differences between the Indian and Australian patients in the current study, it appears the Indian patients are giving an accurate account of what was occurring for them.

The Indian patients were attending a private clinic and chose to answer the English rather than Hindi version of the QOL ED, which confirms they belonged to the middle to high SES rather than lower SES groups.[12] One paper has suggested that AN was more common in middle to high SES groups whereas BN was indicative of a low to middle SES.[4] Further research should recruit a more diverse group of Indians patients from different SES groups, different clinics and different areas of India with varied degrees of exposure to western influence.

In summary, Indian and Australian ED patients scored similarly on the global QOL and engaged in similar ED behaviors, type and frequency. They did differ in ED-related thoughts as Australians were more aware of preoccupation and control feelings surrounding food, eating or body weight and shape. Indians felt their eating and exercise had less impact on their daily social life and relationships, but do recognize a significant effect of their disorder on their medical health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisler I, Dare C, Russell GF, Szmukler G, le Grange D, Dodge E. Family and individual therapy in anorexia nervosa. A 5-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1025–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik SC. Eating disorders. In: Vyas JN, Ahuja N, editors. Postgraduate Society. New Delhi: B. I. Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 260–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makino M, Tsuboi K, Dennerstein L. Prevalence of eating disorders: A comparison of Western and non-Western countries. MedGenMed. 2004;6:49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mammen P, Russell S, Russell PS. Prevalence of eating disorders and psychiatric comorbidity among children and adolescents. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:357–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neki JS, Mohan D, Sood RK. Anorexia nervosa in a monozygotic twin pair. J Indian Med Assoc. 1977;68:98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra PS, Shah A, Shenoy J, Kumar U, Varghese M, Bhatti RS, et al. Family pathology and anorexia in the Indian context. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1995;41:292–8. doi: 10.1177/002076409504100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khandelwal SK, Sharan P, Saxena S. Eating disorders: An Indian perspective. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1995;41:132–46. doi: 10.1177/002076409504100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendhekar DN, Mehta R, Srivastav PK. Bulimia nervosa. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:861–2. doi: 10.1007/BF02730730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendhekar DN, Arora K, Lohia D, Aggarwal A, Jiloha RC. Anorexia nervosa: An Indian perspective. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:181–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tareen A, Hodes M, Rangel L. Non-fat-phobic anorexia nervosa in British South Asian adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:161–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumford DB. Eating disorders in different cultures. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1993;5:109–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lal M, Abraham S. Translation of the Quality of Life for Eating Disorders questionnaire into Hindi. Eat Behav. 2011;12:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abraham SF, Brown T, Boyd C, Luscombe G, Russell J. Quality of life: Eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:150–5. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhugra D, Bhui K, Gupta KR. Bulimic disorders and sociocentric values in north India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:86–93. doi: 10.1007/s001270050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mumford DB, Whitehouse AM, Platts M. Sociocultural correlates of eating disorders among Asian schoolgirls in Bradford. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:222–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta MA, Chaturvedi SK, Chandarana PC, Johnson AM. Weight-related body image concerns among 18-24-year-old women in Canada and India: An empirical comparative study. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:193–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin B, Gluck ME, Knoll CM, Lorence M, Geliebter A. Comparison of eating disorders and body image disturbances between Eastern and Western countries. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03327606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker AR, Walker BF, Locke MM, Cassim FA, Molefe O. Body image and eating behaviour in interethnic adolescent girls. J R Soc Health. 1991;111:12–6. doi: 10.1177/146642409111100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham S. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. Eating Disorders: The Facts. [Google Scholar]

- 20.King MB, Bhugra D. Eating disorders: Lessons from a cross-cultural study. Psychol Med. 1989;19:955–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soh N, Surgenor LJ, Touyz S, Walter G. Eating disorders across two cultures: Does the expression of psychological control vary? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:351–8. doi: 10.1080/00048670701213278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman A, Patel V, Leon DA. Why do British Indian children have an apparent mental health advantage? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:1171–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham SF, von Lojewski A, Anderson G, Clarke S, Russell J. Feelings: What questions best discriminate women with and without eating disorders? Eat Weight Disord. 2009;14:e6–10. doi: 10.1007/BF03354621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]