Abstract

Context:

Recent studies have demonstrated that a high proportion of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients shows an association with psychological factors. A few studies were conducted on the investigation of psychological features of IBS patients in Iran.

Aims:

We aimed to evaluate the relationship of psychological distress with IBS in outpatient subjects.

Settings and Design:

A total of 153 consecutive outpatients met Rome III criteria, and 163 controls were interred to study and invited to complete the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) instrument in order to assessment of psychological distress.

Statistical Analysis:

Univariate (t-test and Chi-square) and multivariate (logistic regression) methods were used for data analysis.

Results:

A significant association of IBS with all nine subscale and three global indices including global severity index (GSI), positive symptom distress index (PSDI), and positive symptom total (PST) of the SCL-90-R were detected. Patients with IBS reported significantly higher levels of poor appetite, trouble falling asleep, thoughts of death or dying, early morning awakening, disturbed sleep, and feelings of guilt compared to the controls. Multivariate analysis indicated that interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, paranoid ideation, depression and phobic anxiety subscales, and PST, PSDI, and GSI global indices were significantly associated with IBS (age, gender, educational level, marital status, employment status, smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index).

Conclusions:

Psychological features are strongly associated with IBS; notably, interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, paranoid ideation, depression, phobic anxiety, and all global indices including PST, PSDI, and GSI is significantly associated with. Hence, the appropriate psychological assessment in these patients is critically important.

Keywords: Global severity index, irritable bowel syndrome, psychological distress, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders characterized by abdominal discomfort associated with altered bowel habits.[1] Recent studies have demonstrated that a high proportion of IBS patients shows an association with psychological factors, especially depression, anxiety, and somatization.[2,3,4] The prevalence of psychiatric disorders including depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and somatization disorder was ranged between 29% and 61% in IBS patients.[5,6] Lydiard and Falsetti[7] reported that 94% of IBS patients had a lifetime prevalence for an Axis I psychiatric disorder. Approximately, 40% of patients with anxiety or mood disorders fulfilled the IBS criteria and IBS was more observed in patients with panic disorders (4-6 times) compared to those without panic disorders.[8]

While some believed that IBS is a biopsychosocial disorder with disturbances of motor function, heightened visceral sensitivity, and possibly central nervous system disturbances,[9,10,11] others suggest that IBS is not a psychiatric disorder, but psychosocial factors influence how the illness is experienced and acted upon.[12] However, there is a considerable of evidence supporting an association between psychological distress, environmental stress, and functional gastrointestinal disorders, especially IBS.[9,13,14] Locke et al.[13] with a nested case–control study on the general population revealed that the psychological distress was significantly associated with the presence of a functional gastrointestinal disorder. Other studies have also observed higher rates of somatization in outpatients with IBS.[14] Given the high prevalence of anxiety-depressive disorders and low quality-of-life scores in IBS patients, it is suggested that psychiatric assessment may facilitate management of the IBS suffers and improve their quality-of-life.[15,16]

Although a range of Iranian studies concerning IBS has been conducted on estimation of the prevalence of IBS,[17,18,19,20] there is a few information on the investigation of psychological features of IBS patients in Iran.[15,16] Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the relationship of psychological distress with IBS in outpatient subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research work was designed as the case–control study. All outpatient subjects visited by the gastroenterologist between October 2010 and October 2011 at Taleghani Hospital gastroenterology clinic, Tehran, Iran, and diagnosed as IBS (according to Rome III criteria) were invited to participate in the study. A control group including individuals who were referred to the other clinics due to medical problems rather than gastrointestinal chief complains was entered to the survey. We compared the psychological state of an outpatient group with the syndrome both with subjects with the syndrome who had not reported having it.

After explanation of the study aim, patients and controls were asked to give their written consent to participate. The study received the approval from Ethics Committee.

All patients and controls asked to complete the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R). SCL-90-R is a 90 item self-administered inventory that used for measuring the psychological problems in the past 7 days. Participants are requested to rate the severity of their symptoms on a five-point scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = no problem-4 = very much) over this period. SCL-90-R has nine subscales (somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychotics) and three global indices (global severity index [GSI], positive symptom distress index [PSDI] and positive symptom total [PST]). GSI, which is obtained by averaging the scores over the total number of items, serves as a reliable measure of psychological distress. The questionnaire has also seven items known as additive items (item 19, 44, 59, 60, 64, 86, 89). The additive items are not pure reflections of one specific dimensional construct, and they are designed to aid in making accurate predictions concerning the respondent's clinical status. They include poor appetite, trouble falling asleep, thoughts of death or dying, overeating, awakening in the early morning, restless/disturbed sleep, and feelings of guilt.

Ability of the each of the SCL-90-R subscales to predict IBS was evaluated by multivariate logistic regression. The disease status was used as the dependent variable and all nine subscales, and three global indices of SCL-90-R served as independent variables in the logistic model. For the aim of controlling confounding effect, demographic variables including age, gender, educational level, marital status, employment status, smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (BMI) were interred in the logistic regression analysis as covariates. The mean scores of additive items were compared using Student's t-test between IBS patients and controls. Background variables were compared by Pearson's Chi-square test (categorical variables) and Student's t-test (continuous variables). All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of participants

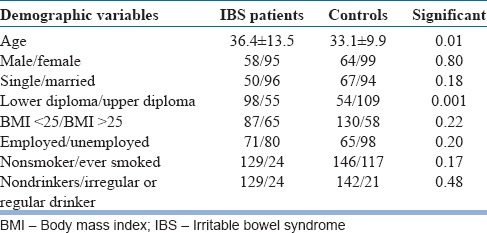

Overall, 153 IBS patients and 163 controls agreed to participate to this study. The profile of IBS patients was similar in terms of sex, marital status, employment status, BMI, smoking habits, and alcohol drinking habits to the control group, except that a lower ages and less educated was more observed in IBS patients compared with controls [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

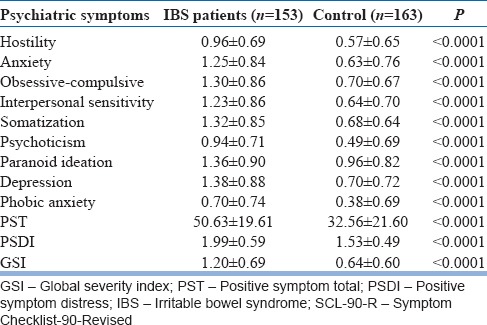

Psychological distress in irritable bowel syndrome patients and controls

The mean scores for the SCL-90-R subscales and three global indices in IBS subjects and controls are given in Table 2. A significant association of IBS with all nine subscale and three global indices scores of the SCL-90-R was detected, with numerically greater mean scores observed in subjects with IBS.

Table 2.

Comparing mean scores of the SCL-90-R GSI, PST, and PSDI and subscales between IBS patients and controls

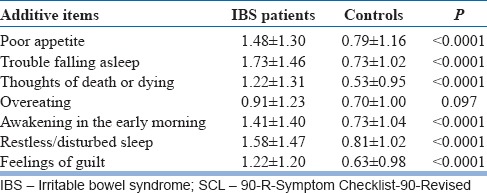

As seen in Table 3, patients with IBS reported significantly higher levels of poor appetite, trouble falling asleep, thoughts of death or dying, awakening in the early morning, restless or disturbed sleep, and feelings of guilt compared to the controls. Further analysis indicated that all of the above difficulties (except overeating) were significantly higher in women with IBS than the control women (P < 0.05). However, men with IBS have experienced more difficulties regarding trouble falling asleep, thoughts of death or dying, restless or disturbed sleep, and feelings of guilt compared to the control men (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Comparing mean scores of the SCL-90-R additive item between IBS patients and controls

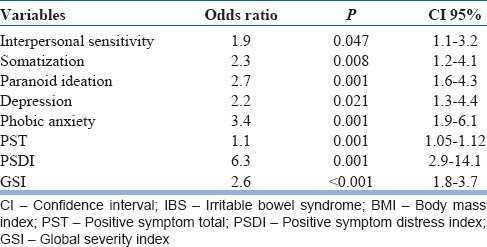

Multivariate analysis indicated that five of the SCL-90-R subscales including interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, paranoid ideation, depression and phobic anxiety, and all global indices including PST, PSDI, and GSI were significantly associated with IBS (age, gender, educational level, marital status, employment status, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of predictors for the development of IBS, adjusting for age, gender, educational level, marital status, employment status, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI

DISCUSSION

In this case–control study, we investigated the association of psychological problems with IBS status. IBS was diagnosed by Rome III criteria, and the psychological features were assessed by SCL-90-R. We also examined the independent psychological predictors of IBS (adjusted for some demographic factors).

We found that IBS was correlated with higher mean scores of all SCL-90-R subscales and PST, PSDI, and GSI indices in univariate analysis. IBS patients like many other medical patient groups, experience levels of depression and anxiety.[4] Clinic patients with gastrointestinal disorders (especially IBS) have higher prevalence of psychological distress (40-60%) compared to healthy individuals (<20%).[4] The most common psychological problems that often precede or occur simultaneously with gastrointestinal disorders are anxiety, depression, panic, posttraumatic stress, and somatization disorders.[6,8,13,14] The American gastroenterological association technical review on IBS reported psychiatric comorbidity about 40-90% of IBS patients referred to tertiary care centers.[21] Locke et al.[13] with a nested case–control study revealed that functional gastrointestinal disorders were more likely to be reported by those with higher scores on each of the nine SCL-90-R scales (except phobic anxiety). Our multivariate logistic regression analysis also showed that interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, paranoid ideation, depression, and phobic anxiety and all global indices including PST, PSDI, and GSI have ability to predict the IBS status independently. Similar to our results, Choung et al.[9] found that all of the SCL-90-R subscales-except phobic anxiety-were independently associated with IBS relative to non-IBS (P < 0.05). Somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, and total life event stress were reported as independent related factors (adjusted for age and sex) for functional gastrointestinal disorders.[13]

Some suggest that coexisting of gastrointestinal symptoms with IBS is associated with an increased level of psychological disorders.[22] A positive correlation between the GSI and the number of gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms was reported by Talley et al.[23] Balboa et al.[24] show that the comorbidity of functional dyspepsia with IBS has a significant negative impact on the psychological status. Unlike the studies mentioned above, others have found that the number of comorbid functional gastrointestinal disorders does not predict the rate and severity of anxiety and depression.[25]

With regards to additive items, we have received more complaints about poor appetite, trouble falling asleep, thoughts of death or dying, early morning awakening, disturbed sleep, and feelings of guilt in IBS patients comparing to controls. There are a few studies on evaluation of nongastrointestinal symptoms such as poor sleep in IBS patients. The prevalence of poor sleep has been reported by 25-30% of IBS patients.[26,27] The frequency of self-reported sleep disturbance in women with IBS (25%) was significantly higher than in controls.[28] Perceived poor sleep was reported by more than half of IBS patients, and it was related to increased IBS symptom severity the next day.[29] Of the most common causes of poor sleep is psychological distress,[30,31] and the level of psychological distress has been shown to be noticeably higher in IBS patients.[32,33] On the other hand, several studies have found an association between BMI with gastrointestinal symptoms[34,35,36] and obesity is associated with disturbed sleep and shorter sleep duration.[37,38] In the present study, BMI was considered as a confounder variable and all analysis adjusted for BMI and some other demographic factors. Our study was clinic-based, and it could have a source of selection bias. Our cases and controls were selected from the clinic and hence it may not be a representative of the general population. Individuals seeking medical care may be psychologically different from the whole population. Furthermore, we did not have any information about diagnosis in the control group that this issue could influence the results. Our findings, therefore, need to be interpreted with caution.

It is an obvious step by steps we can suggest a particular etiological model to explain the occurrence of IBS for discussing the findings from that perspective. We hope, this study done as a background for other researches in IBS Iranian patients. In conclusion, psychological features are strongly associated with IBS; notably, interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, paranoid ideation, depression, phobic anxiety, and all global indices including PST, PSDI, and GSI is significantly associated with IBS independent of age, gender, education level, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI. Hence, the appropriate psychological assessment in these patients is critically important.

Footnotes

Source of Support: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Longstreth GF. Definition and classification of irritable bowel syndrome: Current consensus and controversies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:173–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budavari AI, Olden KW. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:477–506. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(03)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, Svedlund J, Toner BB, Whitehead WE. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II25–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–58. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creed F. The relationship between psychosocial parameters and outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Med. 1999;107:74S–80. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masand PS, Kaplan DS, Gupta S, Bhandary AN, Nasra GS, Kline MD, et al. Major depression and irritable bowel syndrome: Is there a relationship? J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lydiard RB, Falsetti SA. Experience with anxiety and depression treatment studies: Implications for designing irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials. Am J Med. 1999;107:65S–73. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lydiard RB. Irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, and depression: What are the links? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 8):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Talley NJ. Psychosocial distress and somatic symptoms in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: A psychological component is the rule. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1772–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Coutinho SV. V. Stress and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:G519–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mönnikes H, Tebbe JJ, Hildebrandt M, Arck P, Osmanoglou E, Rose M, et al. Role of stress in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Evidence for stress-induced alterations in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity. Dig Dis. 2001;19:201–11. doi: 10.1159/000050681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drossman DA. Irritable bowel syndrome: The role of psychosocial factors. Stress Med. 1994;10:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locke GR, 3rd, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: A population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koloski NA, Boyce PM, Talley NJ. Somatization an independent psychosocial risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome but not dyspepsia: A population-based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1101–9. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000231755.42963.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modabbernia MJ, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Imani A, Mirsafa-Moghaddam SA, Sedigh-Rahimabadi M, Yousefi-Mashhour M, et al. Anxiety-depressive disorders among irritable bowel syndrome patients in Guilan, Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:112. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamali R, Jamali A, Poorrahnama M, Omidi A, Jamali B, Moslemi N, et al. Evaluation of health related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khademolhosseini F, Mehrabani D, Nejabat M, Beheshti M, Heydari ST, Mirahmadizadeh A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults over 35 years in Shiraz, southern Iran: Prevalence and associated factors. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:200–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Vahedi M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Khoshkrood Mansoori B, Safaee A, Habibi M, et al. Economic burden attributable to functional bowel disorders in Iran: A cross-sectional population-based study. J Dig Dis. 2011;12:384–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorouri M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Functional bowel disorders in Iranian population using Rome III criteria. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:154–60. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoshkrood-Mansoori B, Pourhoseingholi MA, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Sedigh-Tonekaboni B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: A population based study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–31. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corsetti M, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Janssens J, Tack J. Impact of coexisting irritable bowel syndrome on symptoms and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1152–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, Lacy BE, Olden KW, Crowell MD. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2454–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balboa A, Mearin F, Badía X, Benavent J, Caballero AM, Domínguez-Muñoz JE, et al. Impact of upper digestive symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1271–7. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000243870.41207.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikocka-Walus A, Turnbull D, Moulding N, Wilson I, Andrews JM, Holtmann G. Psychological comorbidity and complexity of gastrointestinal symptoms in clinically diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1137–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corney RH, Stanton R. Physical symptom severity, psychological and social dysfunction in a series of outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34:483–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90022-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyhlin H, Ford MJ, Eastwood J, Smith JH, Nicol EF, Elton RA, et al. Non-alimentary aspects of the irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:155–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90082-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarrett M, Heitkemper M, Cain KC, Burr RL, Hertig V. Sleep disturbance influences gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:952–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1005581226265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldsmith G, Levin JS. Effect of sleep quality on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1809–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01296103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benca RM. Sleep in psychiatric disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:739–64. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Billiard M, Partinen M, Roth T, Shapiro C. Sleep and psychiatric disorders. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(Suppl 1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lydiard RB, Fossey MD, Marsh W, Ballenger JC. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychom Med. 1993;34:229–34. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71884-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heitkemper MM, Jarrett M, Cain KC, Shaver J, Walker E, Lewis L. Daily gastrointestinal symptoms in women with and without a diagnosis of IBS. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1511–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talley NJ, Quan C, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Association of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms with body mass index in an Australian cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:413–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delgado-Aros S, Locke GR, 3rd, Camilleri M, Talley NJ, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Obesity is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1801–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talley NJ, Howell S, Poulton R. Obesity and chronic gastrointestinal tract symptoms in young adults: A birth cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1807–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohatsu ND, Tsai R, Young T, Vangilder R, Burmeister LF, Stromquist AM, et al. Sleep duration and body mass index in a rural population. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1701–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sperber AD, Tarasiuk A. Disrupted sleep in patients with IBS – A wake-up call for further research? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:412–3. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]