Abstract

This article describes current knowledge on sexual, mental, and behavioral health of sexual minority (SM) youth and identifies gaps that would benefit from future research. A translational sciences framework is used to conceptualize the article, discussing findings and gaps along the spectrum from basic research on prevalence and mechanisms, to intervention development and testing, to implementation. Relative to adults, there has been much less research on adolescents and very few studies that had longitudinal follow-up beyond one year. Due to historical changes in the social acceptance of the SM community, new cohorts are needed to represent contemporary life experiences and associated health consequences. Important theoretical developments have occurred in conceptualizing mechanisms that drive SM health disparities and mechanistic research is underway, including studies that identify individual and structural risk/protective factors. Research opportunities exist in the utilization of sibling-comparison designs, inclusion of parents, and studying romantic relationships. Methodological innovation is needed in sampling SM populations. There has been less intervention research and approaches should consider natural resiliencies, life-course frameworks, prevention science, multiple levels of influence, and the importance of implementation. Regulatory obstacles are created when ethics boards elect to require parental permission and ethics research is needed. There has been inconsistent inclusion of SM populations in the definition of “health disparity population,” which impacts funding and training opportunities. There are incredible opportunities for scholars to make substantial and foundational contributions to help address the health of SM youth, and new funding opportunities to do so.

Over the past two decades, many studies have reported mental, behavioral, and sexual health disparities among sexual minority (SM) youth—an umbrella term for youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, who engage in same-sex behavior, or who have same-sex attractions (Saewyc, 2011). Meta-analyses have shown significant sexual orientation differences in aspects of suicidality (Marshal et al., 2011), psychological distress and depressive symptomatology (Marshal et al., 2011), and substance use (Marshal et al., 2008). Much of the data that have demonstrated these differences came from probability samples that have included items asking about one or more dimensions of sexual orientation, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) (e.g., Bostwick et al., 2014; Kann et al., 2011). CDC national behavioral and case surveillance data have also demonstrated alarming incidence of HIV infections among young men who have sex with men (MSM)(Balaji et al., 2013; CDC, 2013b).

While acknowledging the importance of addressing these disparities, it is also important to point out that most SM youth are resilient and do not experience these mental, behavioral, and sexual health problems (Herrick, Egan, Coulter, Friedman, & Stall, 2014; Mustanski, Andrews, Herrick, Stall, & Schnarrs, 2014; Mustanski, Garofalo, Herrick, & Donenberg, 2007). There is also reason to be optimistic that positive change in the social determinants (e.g., increasing legalization of same-sex marriage; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Meyer, 2003) of these disparities is rapidly occurring and therefore a future in which these disparities do not exist may be achievable (Mustanski, Birkett, Greene, Hatzenbuehler, & Newcomb, 2014).

There is need for much more health research with SM youth. As we have moved into an era of evidence based healthcare where proof of the effectiveness of an intervention is increasingly required in order to receive funding, SM youth are often left out because of lack of research to demonstrate program effectiveness within this population. This is perhaps most clear in the CDC’s compendium of evidence-based HIV prevention programs, where there are seven best evidence interventions for youth, none of which target adolescent MSM (CDC, 2013a) despite that they represent the majority of infections among youth (CDC, 2014b). Using a program within the compendium is often a requirement to receive HIV prevention funding, and similar requirements exist for other health issues. Without basic research to inform intervention development and clinical trials demonstrating effectiveness, SM all too often are left without proven interventions to address their health needs.

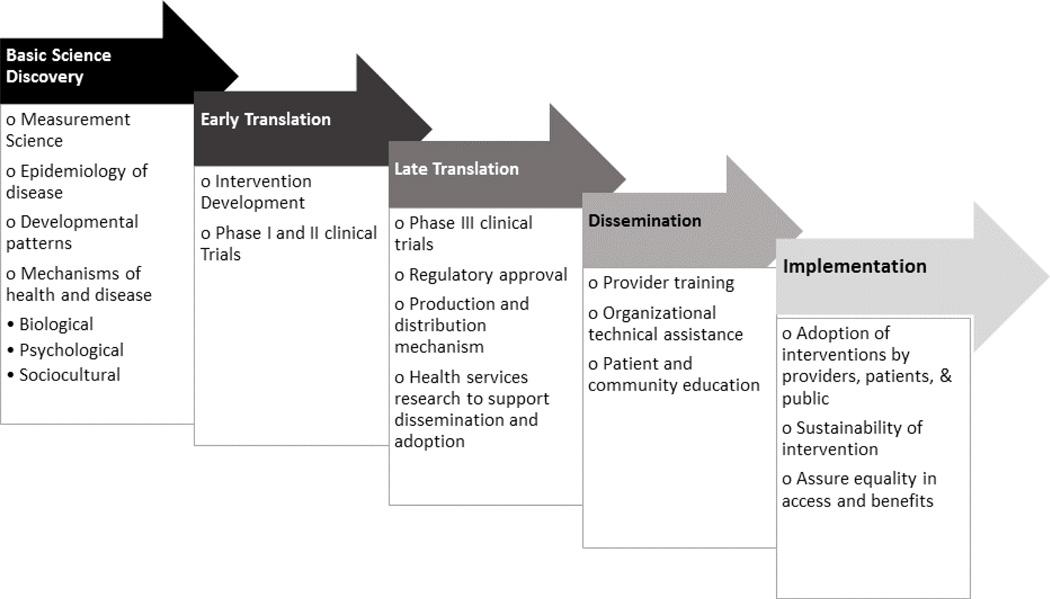

In this article I discuss areas of future research needs and opportunities for SM youth, and also describe some likely obstacles along the way. I utilize a translational science perspective as an organizing framework for describing these opportunities, which was informed by earlier models and descriptions of translational science (Hawk et al., 2008; Spoth et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 1, this translational model of SM health research represents a spectrum from basic research on the measurement and development of sexual orientation and gender identity, to epidemiological research documenting the prevalence and developmental course of health issues among SM youth, to research on the mechanisms that drive disparities and individual differences in health risks and outcomes, to the development and testing of culturally appropriate preventive and treatment interventions, and finally dissemination and implementation research on the effective delivery of services. This model has been highly influential in guiding my own program of research on HIV prevention with young men who have sex with men (MSM), which has crucially benefitted from the interplay of knowledge generated across each of these translational steps. In this article I use this translational model to describe where I believe future research should be headed—beginning with basic research, then discussing intervention research, and closing with some barriers to accomplishing this work.

Figure 1.

Model of translational SM health research

My suggestions for future research directions are focused on sexual minority, rather than gender minority (e.g., transgender), youth because these literatures are somewhat distinct and are at very different phases of scientific development. Research on differences in health outcomes among transgender and gender nonconforming youth has not yet been derived from population-based samples, but community-based samples have reported existence of health disparities (Garofalo, Deleon, Osmer, Doll, & Harper, 2006; Grossman & D'Augelli, 2007; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010). In general there has been relatively little research on the health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth, and the clinical research that has been conducted has tended to focus on outcomes related to gender transitions. As such the science in this area is in a more formative stage, and instead of addressing it here I refer interested readers to other source of reviews and recommendations for transgender health research (Baral et al., 2013; Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities., 2011; Olson, Forbes, & Belzer, 2011; Stroumsa, 2014).

Future Directions in Basic Research

Data from younger samples and longitudinal designs

The overwhelming majority of research on SM health starts with individuals who are age 18 and older, which has been linked to reticence by some Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to issue waivers of parental permission that will allow youth to participate without the risks of disclosing their sexual orientation or gender identity to their parents (see further discussion below and Fisher & Mustanski, 2014; Mustanski, 2011). There have been a relatively small number of studies of samples of SM or MSM participants starting at ages 14 or 16 (e.g., D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Mustanski, DuBois, Prescott, & Ybarra, 2014; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011; Mustanski et al., 2010; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2013; Newcomb, Ryan, Garofalo, & Mustanski, 2014; Rosario, Hunter, & Gwadz, 1997), but even fewer that have longitudinally followed adolescents over multiple years to allow for charting of the developmental course of health issues or the identification of predictors of later health issues (e.g., Bauermeister et al., 2010; Newcomb, Heinz, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2014; Newcomb, Ryan, et al., 2014). Some large longitudinal studies of general samples of youth, such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), have queried sexual orientation of participants as well. The major advantages of asking sexual orientation in these large, population-based samples of youth is their external validity and that they allow for comparisons between SM and heterosexual youth. Another potential advantage—which has not yet been fully exploited—is that some population-based cohorts were started in childhood. As these young children grow into adolescence and young adulthood and some identify as SMs, the data from their self- and family-reports could be used to understand developmental processes and health issues that existed before they self-identified or disclosed a SM status. For example, we know that SM youth are more likely to be gender non-conforming on average in childhood (Bailey & Zucker, 1995), but other differences may exist that can have health implications. General cohort studies that follow individuals from childhood until adolescence and beyond, and assess SM status when developmentally appropriate, can then look back at the earlier data from the SM participants to characterize the unfolding of mechanisms that drive disparities. Such an understanding would create opportunities to put in place innovative, resiliency-promoting resources that provide developmental scaffolding before or during the coming out process—thereby preventing the development of minority stress related health outcomes. Such a resiliency-focused prevention approach would be a revolution from current approaches that focus more on treatment of resulting problems (Mustanski, Birkett, Greene, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2014).

New longitudinal cohort studies of SM youth are needed, both because of the limited prior research, and because existing ongoing cohorts may no longer represent the experience of SMs who are currently teenagers given the rapid change in social acceptance of a SM status (Public Religion Research Institute, 2011; Saad, 2013). This rapid change in social acceptance also creates a challenge for longitudinal cohort studies as it is difficult to disentangle developmental effects from historical change. To disentangle these effects would require the continuous enrollment of new participants into an ongoing cohort study. Doing so would allow for modeling development by history interactions (Cook & Campbell, 1979; Miyazaki & Raudenbush, 2000; Schaie, 1986). As waves of data accumulate, power to detect development by history interactions increases, allowing historical effects to be disentangled from development. When such a design is used, it will be an important advance in our understanding of developmental aspects of sexual orientation, gender identity, and health.

Novel approaches for characterizing mechanism that drive disparities

Much of the early research on the health of SM youth was atheoretical and focused on documenting disparities with those in the majority, and only more recently has research begun focusing on the mechanisms that explain disparities or within-group risk (Saewyc, 2011). Meyer’s minority stress theory (2003) has been popular in research on drivers of health among SM populations. The theory posits that stigma, prejudice, and discrimination create a stressful social environment that causes health problems and articulates a stress process comprised of experiencing prejudice events, expectations of rejection, concealing one’s identity, internalization of society’s homonegativity, and ameliorative coping. Hatzenbuehler (2009) extended minority stress theory in creating a psychological mediation framework that begins with stress as the start of the model and then examines psychological processes, including emotion regulation, social and cognitive processes, through which stress leads to psychopathology. The psychological mediation framework differs from minority stress theory in its inclusion of general psychological processes rather than exclusively minority group-specific processes. Hatzenbuehler’s (2014) work has also highlighted the importance of structural stigma, which represents the “societal-level conditions, cultural norms, and institutional policies that constrain the opportunities, resources, and well-being of the stigmatized” (Hatzenbuehler & Link, 2014, p. 2). These theoretical models of the effects of stigma have been enormously important to the field in their articulation of testable hypotheses about mechanisms, and thereby have helped shepherd research on mechanisms (see reviews by Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013).

While there has been much theoretical advancement in describing forms of minority stress and mediators of these stressors on mental health, there has been little research on moderators that may explain why some individuals are more or less influenced by the exposure to minority stressors (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Moderators of minority stress could include pre-existing individual characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, personality, coping skills), interpersonal factors (e.g., family support), as well as structural factors (e.g., anti-bullying policies in schools). Future theory-driven research on moderators would be particularly valuable in identifying individuals who are at increased risk of negative health outcomes under minority stress exposures as well as modifiable factors that could help lessen the impact of such stressors.

Family Based Research

Longitudinal designs are powerful for testing the mediational mechanisms articulated in these theoretical models, but as described above they have been relatively rare in research on SM health. Research on structural stigma has also been rare, and instead most studies have focused on individual processes (Hatzenbuehler, 2014). Innovation is needed in methodologies that can more rigorously characterize the mechanisms driving disparities. One design that has incredible potential, but has rarely been used is the sibling comparison design (Balsam, Beauchaine, Mickey, & Rothblum, 2005). With this approach, a SM is matched with a non-SM sibling and within-family analyses are conducted on relationships between putative mechanisms and outcomes. The major advantage of this approach is it controls for family-level processes, thereby avoiding confounds inevitable in comparisons of unrelated youth (e.g., family factors may explain differences rather than individual-processes; Dick, Johnson, Viken, & Rose, 2000). Furthermore, between-family factors (e.g., social class, religiosity, conservatism) may act as mediators or moderators of individual effects. For example, experiences of bullying may be more common for the SM child in a sibling pair, and its effects may be more toxic in families that are less accepting. Without a family-based design such associations cannot be resolved.

Along these same lines, studies of parents of SM children are almost non-existent in the literature, which is a major void. Some studies have been done with parents of SM young adults in their early- to mid-20s (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009), but there have been very few studies of parents of SM teens. One exception was a small qualitative study of seven White, middle-class, suburban parents in New England, which described the meaning parents ascribe to learning that an adolescent is gay or lesbian, how adolescent disclosure affects the solidarity of the parent–child relationship, and what interventions support healthy parent adjustment (Saltzburg, 2004). There have also been many studies of SM adolescents who report on relationships with their parents, which have found significant cross-sectional (e.g., Garofalo, Mustanski, & Donenberg, 2007; Mustanski & Hunter, 2009; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011) and longitudinal (e.g., Mustanski & Liu, 2013; Newcomb, Heinz, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2013; Newcomb, Heinz, & Mustanski, 2012; Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003) associations of perceived parental social support and acceptance with multiple health behaviors and outcomes. Yet these one-sided designs omit critical information needed to understand these bi-directional relationships, and literature with heterosexual youth has clearly shown that parent and child reports convey unique information (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). As such, lack of data from parent reports limits our understanding of the impact of parenting factors—such as acceptance, social support, monitoring, warmth, and communication—on outcomes in SM youth. Absence of involvement of parents in research also stands in the way of creating family-based interventions that could have profound and sustained impacts on the health and development of SM youth (Bouris et al., 2010; Garofalo et al., 2007).

There are some very substantial methodological issues that will need to be addressed in order to conduct research with parents of SM teens. The paramount issue is one of ascertainment. In my experience, organizations that provide important support services to parents of SM children (e.g., PFLAG) are often willing to collaborate on research, but most of the parents who attend such programs have adult SM children rather than teenagers. For example, in one survey of parents of SM children recruited through PFLAG chapters the mean age of the parents (58.7 years) suggests most parents had adult children (Conley, 2011). Recruitment of parents of SM teens from the general population of parents, such as through schools, would require screening of a very large number of parents in order to identify a sufficient sample who report a SM child. With such an approach there will be concerns about bias in terms of which parents are willing to report on a screening survey that they have a SM child. Another option is to recruit SM teens and ask them to invite their parents to participate in research. Unfortunately, there is evidence that a substantial proportion of SM youth would be unwilling to do this, and this is even more so the case with racial/ethnic minority youth (Mustanski, 2011).

In using approaches where recruitment begins with either the parent or the SM child there will be concerns about bias in which parents are aware of their child’s SM status, as not all children disclose during adolescence. In this regard, there are historical changes with age of coming out appearing to be declining (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006b). Racial/ethnic minority youth appear to be less likely to come out to their parents (Grov et al., 2006b; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011), which suggests that studies in which parental involvement is required may be biased against racial/ethnic minority participation. Furthermore, the parents who do know their child’s SM status and are willing to report it in a screener, or have children who feel safe approaching parents for research involvement, may be more accepting than average, which could severely limit the external validity of study findings. Such limitations would be unacceptable for an epidemiological study seeking to report the prevalence of health issues among SM youth as the reports of youth able to include their parents in the study will not generalize to the larger population of SM youth. However, if the goals are more intervention-focused, such as developing a family-based prevention program, then it may be satisfactory to begin a program of such research with families where parents are aware and accepting of their child’s SM status, with an acknowledgement that in the future more families will likely have such acceptance and that future studies could explore approaches to involve less accepting parents. In sum, I do not believe it is scientifically or ethically advisable to require parental permission for epidemiological research, nor for many types of interventions aimed directly at the child (see discussion on IRBs below). However, I do think the time is ripe to begin developing and testing family-based health interventions for SM youth, which I believe have tremendous untapped potential.

Research on Romantic Relationships

In addition to the need for designs that involve siblings and parents, there is also great need for study of romantic relationships among SM youth. Even in the area of research on HIV among young MSM—a health issue explicitly linked to the transmission of a virus within a sexual dyad—most research has focused on individuals rather than both partners (Karney et al., 2010; Mustanski, Starks, & Newcomb, 2014). Beyond HIV there are important reasons to consider romantic relationships’ effects on mental and behavioral health among SM youth, as well as to advance basic understanding of the development of romantic relationships (Diamond, Savin Williams, & Dube, 1999; Furman, Brown, & Feiring, 1999). From a developmental perspective, initiating romantic relationships and developing romantic competencies is one of the primary tasks of adolescence and young adulthood, and skills developed in this period will have implications later in life. In terms of mental health, the association with aspects of romantic relationships has been complex; on balance the research, primarily with heterosexual youth, suggests positive dating experiences in middle-to-late adolescence have beneficial effects on mental health, self-esteem, and social acceptance (Connolly & McIsaac, 2011). Bauermeister has been a leader in conducting research on adolescent same-sex romantic relationships in terms of characterizing ideal romantic relationships (Bauermeister et al., 2011) and their influences on mental and behavioral health (Bauermeister et al., 2010; Bauermeister, Ventuneac, Pingel, & Parsons, 2012). For example, in one longitudinal study he found that being in a same-sex relationship had different effects on psychological well-being depending on sex (Bauermeister et al., 2010). In our own mixed-methods studies we described longitudinal associations between romantic relationship status and engagement in HIV risk behaviors (Mustanski, Newcomb, & Clerkin, 2011; Newcomb, Ryan, et al., 2014) and qualitative interviews with young same-sex couples on condom use and relationship stages and processes (Greene, Andrews, Kuper, & Mustanski, 2014; Macapagal, Greene, Rivera, & Mustanski, under review). In terms of future directions, more research is needed on the development of healthy same-sex relationships in adolescence, particularly research on effective strategies used by SM youth to initiate and maintain healthy relationships.

Conducting research with young same-sex couples will have its challenges. Firstly, most individuals would be unwilling to ask a new romantic partner to participate in a research study with them, and therefore it may be difficult to study couples at very early stages of relationship formation. This exclusion of couples in more casual relationships or at very early stages of dating may not be problematic for some research topics. For example, in the domain of HIV/STIs research shows the majority of unprotected sex and HIV transmission occur within serious relationships (e.g., Bingham et al., 2003; Hays, Kegeles, & Coates, 1997; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Clerkin, 2011; Newcomb, Ryan, et al., 2014; Stueve, O'Donnell, Duran, San Doval, & Geier, 2002; Sullivan, Salazar, Buchbinder, & Sanchez, 2009). For research on other health topics it may be particularly critical to enroll couples at earlier stages in the relationship or to observe the relationship unfold from initial meeting, but of course this is a challenge not inherent to SM research. One creative solution is for researcher to create and/or recruit couples from speed-dating events (Finkel, Eastwick, & Matthews, 2007).

Research on romantic relationships will be relevant even in a future where sexual stigma is absent because of the reality that the small proportion of youth interested in same-sex relationships reduces the quantity of available partners as well as accessibility of partners through traditional settings such as schools (Mustanski, Birkett, Greene, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2014). As such, innovative research methods are needed now and into the future for facilitating the development of healthy same-sex relationships and relationship skills among SM adolescents.

Research simultaneously examining multiple levels of analysis

A final comment on need for innovation in mechanistic research is that there is also need for the development of study designs that examine multiple level of analysis (i.e., from cells to society) to understanding how stigma “gets under the skin” and ultimately impacts health (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Most prior stigma research has taken place in laboratories or in single communities (Hatzenbuehler, 2014). These approaches allow for understanding of mechanisms that link stigma to physiological and psychological responses and for understanding individual experiences of stigma, but these approaches are less useful for studying structural stigma, which requires large-scale studies with samples residing in multiple geographic regions. Even when such designs can be achieved, the findings are often correlational. Some innovative “natural experiments” have been reported (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010) and more innovation is needed using such approaches. Furthermore, we need studies that integrate across these levels of analysis so that we can characterize causal pathways leading from structural factors to individual experiences, to biobehavioral responses, and ultimately to resulting health outcomes.

Methodological Innovation Needed in Sampling SM Adolescents

As described in a report by the Institute of Medicine (2011) on the health of LGBT people, sampling is a significant challenge to research in this population for multiple reasons: sexual orientation and gender identity are multifaceted concepts and defining them can be operationally challenging; individuals may be reluctant to identify as a SM; and because the SM population is a relatively small proportion of the general population it is labor-intensive and costly to recruit a large enough sample in general population surveys for meaningful analysis. For these reasons, research on the SM population most commonly uses nonprobability sampling methods (although the list of important exceptions is growing, such as the CDC's Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System: Kann et al., 2011; Mustanski, Van Wagenen, Birkett, Eyster, & Corliss, 2014), and results from these non-probability studies have had tremendous value for understanding and addressing SM health disparities. These designs have included “convenience,” venue-based, and chain-referral approaches, each of which has their own strengths and limitations and most of which have primarily been implemented with adults.

Venue-based sampling approaches, which have been used for epidemiological research on HIV among adult MSM (e.g., CDC, 2010), may not function well with adolescent samples as there are few venues where SM adolescents congregate on a regular basis (although they have been used with adolescent and young adult MSM; for an example see MacKellar, Valleroy, Karon, Lemp, & Janssen, 1996). Recruitment from venues where some SM youth congregate, such as agencies that serve SM youth with social service needs, may create issues with external validity as youth seeking services from these agencies likely have higher levels of health or social needs than the general SM youth population.

For a period there was tremendous interest in the use of Respondent Driven Sampling to recruit SM populations (RDS; Heckathorn, 1997). RDS is an incentivized chain referral sampling method designed for “hidden” samples that has been found under some conditions to produce unbiased estimates of a population. Unfortunately, research attempting RDS with adolescent MSM suggests inherent characteristics of these networks (e.g., small network size) may not allow RDS to reach the desired populations size or meet underlying assumptions of the method (Kuhns et al., 2014; Phillips, Kuhns, Garofalo, & Mustanski, 2014). While it may function as a valuable tool to recruit youth who might not be directly reachable by researchers but can be reached by peer participants, the requirements to calculate sampling weights may not be met.

When questions about SM status are added to large probability samples it has tremendous value for estimating the size of the SM population and the prevalence of health issues. For example, sexual orientation items have recently been added for the adults in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS; Ward, Dahlhamer, Galinsky, & Joestl, 2014); with a total sample size of 34,557 adults, this recent sample included 2.3% lesbian, gay, or bisexual identified individuals. Probability samples of this magnitude are rare, and most are much smaller. Because of the relatively small proportion of SM people within the population, often estimates from such studies are relatively imprecise. This limits the use of such data to examine sub-groups within the SM population. This limitation is substantial as available data indicates that these sub-groups are heterogeneous when it comes to health issues (e.g., sex differences: Bostwick et al., 2014; gay versus bisexual differences: Mustanski, Andrews, et al., 2014). The small size of the SM population creates another issue that even a small proportion of youth who falsely endorse a SM identity label can threaten the validity of findings for the target SM population. For example, Savin-Williams and Joyner (2014) recently observed that 70% of adolescents who reported either both-sex or same-sex romantic attractions at wave 1 of the Add Health study identified as exclusively heterosexual as Wave 4 young adults. They proposed that this was likely due to a combination of confusion about the wording of the same-sex attraction item and “jokesters” who reported same-sex attraction when none were present. Recently there has been much interest in best methods for assessing sexual orientation in population health studies, including the use of follow-up questions and probes to help reduce misclassification due to participant confusion and clarify when an individual cannot answer because they are still coming to understand their sexuality (a particularly important consideration for youth)(CDC, 2014a; Institute of Medicine, 2011; The Williams Institute, 2009). A commentary on Savin-Williams and Joiner pointed out that it is important to acknowledge that sexual orientation is a multidimensional construct and that inconsistency across reports or attractions and identity labels are to be expected (Li, Katz-Wise, & Calzo, 2014; for a discussion of the multidimensional nature of sexual orientation see Mustanski, Kuper, & Greene, 2014). It is also important to understand that adolescence is a time of identity and sexual development, and therefore excluding individuals who are unsure of their sexual attractions or what (if any) identity label to adopt risks mis-specifying the SM population. For example, in our developmental research on SM youth we often utilize broad inclusion criteria: identify as LGBTQ, experience same-sex attraction, or engage in same-sex behavior. For some studies inclusion criteria are more restricted (e.g., engagement in same-sex contact for research on HIV). Inclusion criteria are an important nuanced consideration for research with SM youth and need to be appropriate for the aims of the particular study.

Another important limitation of nearly all large, probability surveys is that due to their population-wide focus they do not assess constructs that are important drivers of health issues in SM populations, such as discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity or access to gender-affirming healthcare. Without measuring such constructs, probability sample studies will always be limited in their ability to characterize mechanisms that drive health issues in the SM population.

Given the strengths and limitations of probability and non-probability samples, these represent complimentary approaches that are both necessary to advance understanding of the health of SM youth. Further, the limitations of existing probability and non-probability sampling methods for SM youth make this an area ripe for future research on new methodologies and their external validity. For example, in the area of probability sampling, methodological research should be conducted to demonstrate how to effectively over-sample SM individuals in order to allow more precise estimates, particularly within sub-groups. In research using non-probability sampling designs, more understanding is needed on how to efficiently recruit SM individuals and how to maximize external validity. In the absence of a principled sampling methodology for this population, grant applications focused on understanding and addressing the health of SM youth are inherently at a disadvantage in comparison to proposals focused on populations where validated methods exist. As such, methodological research should be considered a priority area for the future, which is consistent with the recommendation of the Institute of Medicine report (2011).

Consideration of Intersectionality

A small but growing literature has begun to apply an intersectionality perspective to examine how race/ethnicity, geographic location, socioeconomic status, gender identity, and other marginalized positions in society contribute to health disparities among SMs and how these factors may modify minority stress processes and intervention approaches (for a review of this literature among SM youth see Mustanski, Kuper, et al., 2014). Coined by Crenshaw (1989), the intersectionality perspective emerged from feminist scholarship, as well as critical race theories, and aims to understand social inequality across these multiple social dimensions (Bowleg, 2008; Cole, 2009; Davis, 2008). In relation to sexual orientation development, the Intersectionality perspective emphasizes that the experience of being a SM tends to vary by the racial or ethnic group with which one identifies, as well as by other factors such as socioeconomic status (Chae & Ayala, 2010; Herek, Norton, Allen, & Sims, 2010; Mustanski, Birkett, Greene, Rosario, et al., 2014; Ross, Essien, Williams, & Fernandez-Esquer, 2003).

Research on the impact of race/ethnicity on SM identity development has been mixed. Some investigators have reported that there are no significant differences in the timing of psychosexual milestones or in sexual identity formation (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006a; Rosario, Meyey-Bahlburg, Hunter, & Exner, 1996) while others have found distinct racial/ethnic differences in the timing of certain milestones (Dube & Savin-Williams, 1999). Models have also been proposed for interaction in the development of sexual and racial/ethnic identities (Collins, 2000; Jamil, Harper, & Fernandez, 2009), with some literature highlighting cultural conflicts (Parks, Hughes, & Matthews, 2004; Wilson & Miller, 2002; Wilson, 2008), while others have suggested resiliencies associated with multiple minority identities (Bowleg, Huang, Brooks, Black, & Burkholder, 2003; Meyer, 2010). Moving beyond race/ethnicity, there is increasing appreciation in the literature for differences in the development of sexual orientation based on sex and gender (e.g., Diamond, 2012).

In terms of future directions in applications of intersectionality to psychological research on SM youth, greater specificity of the perspective and methodological development are needed. Controversies continue about whether Intersectionality is a theory, a heuristic device, or a method for doing feminist analysis (Davis, 2008). Scholars also have debated which categories (and how many) should be included in intersectional analysis and whether categories should be used at all. There are disagreements on the focus and scope of Intersectionality, but a general consensus that intersectionality would benefit from a broadly accepted definition and a methodology explicating how, where, and when it should be applied (Davis, 2008).

Future Directions in Intervention Research

To date, most research on SM youth has been descriptive, and to a lesser extent mechanistic, but very little has focused on developing, testing, or disseminating interventions. To a large extent this reflects the typical progress of health research, which often begins by identifying the extent of the health issue, studies its drivers, and finally utilizes this information to develop interventions. The progression along this continuum perhaps has been slower for research with SM youth, likely due to a combination of challenges I address in the next section, but I believe the time has come for an expansion of intervention research.

Why do we need intervention research specific to SM youth?

SM youth are impacted by unique cultural, contextual, and developmental factors that need to be addressed in interventions (Coker, Austin, & Schuster; Garofalo & Harper, 2003; Harper, 2007a; Meyer, 2003; Mustanski, Newcomb, DuBois, Garcia, & Grov, 2011; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2006). Consider the case of HIV prevention. Young MSM share some common risk/protective factors with other young men, but also have unique experiences. For example, family support is protective against HIV risk in all youth (Garofalo, Mustanski, & Donenberg, 2008; LaSala, 2007; Ryan et al., 2009), but “coming out” and its implications for effective parental monitoring and support is an issue unique to SM youth. Taking this example further, a young man who is having sex with other males and believes he may have acquired a sexually transmitted infection may be particularly reticent to involve his parents in accessing healthcare services if he is not out to his parents and therefore particularly worried about answering questions about his sexual behavior. The role of sociosexual contexts are also dramatically different for young MSM than their heterosexual peers (e.g. online/smartphone hook up sites; Harper, 2007b; Mustanski, Newcomb, Du Bois, Garcia, & Grov, 2011). In the domain of mental health, accumulating evidence shows that the chronic stress experienced by SM individuals can be accounted for by unique experiences like sexual orientation-based victimization, perceived stigma, and internalized homophobia (Meyer, 2003). Furthermore, navigating the development of a SM identity can be a particularly stressful time both in terms of self-acceptance and dealing with disclosure and reactions of others (e.g., Jadwin-Cakmak, Pingel, Harper, & Bauermeister, 2014). These are just a few examples of the myriad ways in which SM-status needs to be considered in interventions addressing mental, behavioral, and sexual health and therefore why targeted interventions are needed.

Furthermore, it is also important to recognize SM as a heterogeneous group. For example, a health intervention that is culturally responsive to the needs of a lesbian-identified youth may not address all of the needs of a bisexually-identified young woman. Who should the intervention be tailored for and targeted to in its delivery? In parallel, who will get left out if tailoring and targeting are restricted? Reviews of the literature have reported that culturally adapted treatments were more effective than non-adapted treatments (Smith, Rodriguez, & Bernal, 2011) and that adapted interventions have positive effects on clients’ engagement, retention, and satisfaction (Griner & Smith, 2006). An alternative to tailoring and targeting content to SM individuals is to develop broad-based universal interventions for all youth that incorporate content that is valuable to SM youth. Such an approach may be more likely to reach SM youth that do not identify as LGBTQ, but the dose of relevant intervention material may be curtailed. The pros and cons of each of these complementary strategies needs to be considered early in intervention conceptualization.

Attempting to intervene on sexual orientation

One longstanding issue that has recently received increased attention in the media and policy circles is so called “reparative therapy”—approaches that claim to be able to change an individual’s sexual orientation. Since research on psychoanalytic and unpleasant conditioning-based approaches to changing sexual orientation proved unsuccessful, research in this area waned since the 1970s (Drescher, 1998; Zucker, 2003), and with continuing research providing no support for change efforts (Spitzer, 2012). Currently, every major professional mental health organization has issued position statements that such practices are not only ineffective but also harmful (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2009). More recently, several states have passed laws prohibiting such practices, but little has been written about the long term effects of exposure or how to support SM youth in recovering from such experiences.

Intervening to improve SM health

In the absence of evidence-based prevention and clinical interventions targeted or validated with SM youth, this is a major area of future research. A number of theoretical perspectives may be particularly useful in informing intervention development for SM youth. First, interventions should be developed to promote and build on natural resiliencies in the face of chronic SM stressors. SM people are prone to developing deficits in emotion-regulation skills as a result of the early experiencing of chronic stress (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003). Efforts to promote healthy emotion regulation and copings skills can help SM youth establish resiliency in the face of these chronic stressors. Research on the natural resiliency-promoting processes among SM youth, such as investing self-worth in domains more intrapersonally controllable than other’s approval (e.g., personal academic achievement), may help inform interventions (Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013). Such interventions will need to be mindful that research has shown that overinvestment in achievement domains is also associated with psychological costs (Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013). This consequence could be avoided by helping SM youth balance their self-worth across multiple domains. More research is needed on the long-term effects of coping strategies utilized by SM youth, as some may be adaptive in the short term but maladaptive in the long-term (e.g., erecting self-protective emotional walls against victimization in adolescence, which may make it difficult to later develop health interpersonal relationships).

Intervention research may benefit from utilizing a framework that emphasizes prevention and health promotion in the context of the life-course, thereby acknowledging that there is an accumulation of events at each stage of life that shapes and influence later stages (Institute of Medicine, 2011; O'Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009). This perspective also emphasizes the prevention, rather than the treatment, of adverse health outcomes, and it stresses the importance of scaffolding youth before, or during, periods of vulnerability to avert adverse health outcomes. Using a prevention approach is not only cost-effective, but it helps to avoid the pain and suffering associated with health issues (O'Connell et al., 2009). Behavioral prevention and promotion approaches for SM adolescents in the area of sexual health have just begun to emerge in the literature (e.g., Hidalgo et al., 2014; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2011; Mustanski, Garofalo, Monahan, Gratzer, & Andrews, 2013; Mustanski, Greene, Ryan, & Whitton, 2014), but preventive interventions for mental disorders, suicidality, and substance use have lagged and such research is vital.

One important challenge of a prevention framework for SM youth is identifying and reaching them before or during their period of vulnerability. How do you reach a SM youth with a targeted intervention before they have come out to anyone? This challenge is perhaps why online research with SM youth continues to thrive since it began in the late 1990s (Mustanski, 2001). Because SM use the internet and mobile technology to explore their sexuality and seek resources and romantic partners (Magee, Bigelow, Dehaan, & Mustanski, 2012; Rice et al., 2012), it creates an opportunity to reach them early in the process of their identity exploration and to diffuse interventions (Burrell et al., 2012; Holloway et al., 2013; Silenzio et al., 2009; Ybarra, DuBois, Parsons, Prescott, & Mustanski, 2014). Research using innovative approaches to online and mobile sexual health interventions with SM youth will surely continue to thrive and expand (Allison et al., 2012), and these successes can serve as a roadmap for eHealth and mHealth interventions focused on mental and behavioral health.

A final comment on frameworks for intervention development is that for SM to achieve health equity multiple levels of the ecodevelopmental context will need to be addressed (Mustanski, Birkett, Greene, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2014), including the social and policy landscape (i.e., social stigma, legal discrimination), institutions (e.g., schools), neighborhoods and communities (e.g., community violence), romantic relationships (e.g., relationship education programs that encompass same-sex relationships), families (e.g., parental acceptance, effective parenting), and individual SM youth (e.g., coping skills). Because psychologists tend to focus on individual-level factors, much research on SM mental, behavioral, and sexual health has been oriented to the individual-level (e.g., individual experiences of victimization, motivations, etc) rather than other more external ecodevelopmental levels. Multilevel models for intervention have begun to be explicated in areas such as HIV prevention (e.g., Johnson et al., 2010) and there are a few examples of studies of structural interventions or policies on SM mental health (e.g. school anti-bullying policies: Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013). Testing effects beyond the individual level and characterizing interactions across levels are important areas of future research.

Once interventions are developed and validated, I believe it is important for their developers to support their dissemination and implementation, ideally in partnership with implementation scientists who can inform the best methods for uptake and translation of the intervention into routine practice. This is no small feat, and universities are often under-equipped to support implementation initiatives. They also tend to reward innovation rather than what is sometimes considered to be the prosaic work of disseminating or supporting the implementation of something already validated (see recent editorial on universities and HIV implementation science: El-Sadr, Philip, & Justman, 2014). In my own work I have found nothing more satisfying than to have witnessed my epidemiological research inform the development and pilot testing of a new intervention, the intervention subject to a randomized clinical trial, and then begin supporting the implementation of that intervention at the community-level. There is a long road ahead for the study and implementation of my own interventions, but as a future research direction I hope the field will move further towards embracing the channeling of scientific findings into action for the benefit of SM youth.

Challenges to research on the health and development of SM youth

Regulatory obstacles

Beyond the methodological challenges described above (e.g., sampling), a number of other obstacles have challenged research efforts to improve the health of SM youth. One is reticence by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to waive requirements of parental permission for research with SM youth (Fisher & Mustanski, 2014; Mustanski, 2011). Available and emerging data suggests that, without such waivers, studies of SM youth cannot reasonably be conducted because too many SM youth are unwilling to approach their parents for permission, and those willing differ vastly on a range of outcomes (Mustanski, 2011). This lack of willingness to involve parents in the research or parental permission process is beyond general teenage reluctance to involve their parents in activities as they navigate the transition to independence, but instead stems from the real threat that discussing their SM status with parents could result in victimization, abuse, or being expelled from the home (Friedman et al., 2011; Keuroghlian, Shtasel, & Bassuk, 2014). Therefore, approaching their parents to participate in a study of SM youth may open them up to abusive experiences; an unnecessary risk when federal regulations outline that in such situations parental permission can be waived (Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Research has not yet sufficiently documented the perspectives of SM youth on the risk and benefits of participating in health research, nor has it produced a rich understanding of the range of reasons SM youth are reluctant to involve their parents; ethics research in this area is an important future direction.

Many HIV epidemiological studies have been approved without requirements of parental permission based on the grounds that federal regulations define a child based on the consent laws of the local jurisdiction, and most states allow individuals under age 18 consent to HIV testing and counseling with no parental notification requirement (for discussion see Nelson, Lewis, Struble, & Wood, 2010; for example of study of MSM ages 15+ years in seven states see Valleroy, MacKellar, & Karon, 2000). However, there is much confusion and disagreement among ethicists, IRBs, and child health researchers about the interplay and application of federal and local regulations when it comes to young people’s ability consent to research using tests and treatments that would not require parental permission in clinical practice (Fisher & Mustanski, 2014; Institute of, 2004; Mustanski, 2011), and therefor this area is ripe for future policy research.

Preventing research that will help improve the health of SM youth by requiring parental permission when it is unfeasible, or requiring samples to start at age 18 years, is in conflict with current ethical discourse focusing on youths’ right to participate in studies that will protect them from receiving developmentally untested, inappropriate, and unsafe treatments (e.g., Nelson et al., 2010). Because allocations for services are driven by epidemiological data, and funding for prevention/treatment programs requires evidence of program effectiveness, blocking such research perpetrates disparities.

Lack of consistent recognition of SM populations as a minority or disparity population

SM populations are inconsistently included in the definition of minority and disparity populations in reports on minority representation in the scientific and healthcare workforces, and in funding opportunities to increase the pipeline of underrepresented minorities in these employment sectors. Without clear data it is impossible to know their degree of representation or underrepresentation. In my experience with students and colleagues, there are very few Psychology faculty members in graduate institutions who are conducting research on SM health, and even fewer who focus on youth. This creates an inherent pipeline issue as there are few faculty to mentor graduate students with these interests. As such, there have been calls for training grants that use innovative approaches such as brief intensive trainings or networks of mentors that can help address this pipeline issue (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Two examples of this are the NIH-funded Fenway Summer Institute in LGBT Population Health and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)-funded clinical psychology internship program in LGBT Health that is a partnership between Northwestern University and the community-based behavioral health program at Center on Halsted. We need more such programs if we are going to have a sufficient cadre of researchers and clinicians with cultural competence in SM health to address health disparities.

There is also inconsistency across and within federal and foundation funding announcements regarding the inclusion of SM populations as health disparity populations. For example, SM populations were included for the first time as a disparity population in the federal Healthy People 2020 goals for addressing health disparities in the U.S. (United States Department of Health & Human Services, 2010), MSM were identified as a key disparity population in the National AIDS Strategy (White House Office of National AIDS Policy, 2010), and SMs are sometimes identified as a disparity population in NIH funding announcements. However, unless the directors of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the National Institute of Minority Health Disparities (NIMHD) jointly designate SM as a disparity population ("Minority health and health disparities research and education act of 2000,"), then they will not be consistently included. The “health disparity” designation was created because despite notable progress in the overall health of the U.S., there are continued disparities in the burden of illness and death experienced by minority populations, who are also underrepresented in the biomedical and behavioral science workforce. Funding to address these disparities and underrepresentation was then allocated to advance equity. As such, advocacy for this designation is important in terms of recognition of the existence of inequities and for access to resources to help ameliorate them.

Conclusions

In this article I have sought to lay out my perspectives on important future research directions in mental, behavioral, and sexual health of SM youth. The evidence for the need for translational research is clear, as we have much evidence of the existence of health disparities, but less understanding of mechanisms (particularly beyond the individual level), and even less evidence for effective approaches for ameliorating or eliminating these disparities. Entire areas of scholarship that are well developed in “general samples” remain almost entirely unexplored with SM youth (e.g. research that includes parental participation). A few well known and cited longitudinal studies have been conducted with SM adolescents, but few have followed the sample for more than one year with adequate retention. Intervention research with this population is just in its infancy. Depending on how you see it, the glass is either half-empty or half-full. Research in this area has been slow and there are important methodological and logistical obstacles that have not been fully surmounted. Much is not known about SM health. On the other hand, there are incredible opportunities for scholars to make substantial and foundational contributions to this field and to help address the health of SM youth, which is an excellent opportunity for early career scholars. Furthermore, it is an exciting time to be conducting this research as an abundance of funding opportunities focused on SM health have been recently issued by federal and foundation organizations for the first time, creating new opportunities for research and training.

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this article, Dr. Mustanski was supported on research grants focused on sexual minority mental, behavioral, and sexual health from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01DA036939, R01DA035145, R01DA025548), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH096660, R21MH095413), and a grant for the training of psychology interns from the Health Resource and Services Administration (D40HP25719). I thank Dr. Michael Newcomb for providing feedback on this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Health Resource Service Administration, or those who provided feedback on the manuscript.

References

- Allison S, Bauermeister JA, Bull S, Lightfoot M, Mustanski B, Shegog R, Levine D. The intersection of youth, technology, and new media with sexual health: Moving the research agenda forward. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Task force on appropriate therapeutic responses to sexual orientation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JM, Zucker KJ. Childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation - a conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Bowles KE, Le BC, Paz-Bailey G, Oster AM, Group NS. High hiv incidence and prevalence and associated factors among young msm, 2008. AIDS. 2013;27:269–278. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ad489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Mickey RM, Rothblum ED. Mental health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings: Effects of gender, sexual orientation, and family. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:471–476. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of hiv in transgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2013;13:214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Pingel E, Eisenberg A, Santana ML, Zimmerman M. Measuring love: Sexual minority male youths' ideal romantic characteristics. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2011;5:102–121. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2011.574573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Sandfort TG, Eisenberg A, Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:1148–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Ventuneac A, Pingel E, Parsons JT. Spectrums of love: Examining the relationship between romantic motivations and sexual risk among young gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1549–1559. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0123-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham TA, Harawa NT, Johnson DF, Secura GM, MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA. The effect of partner characteristics on hiv infection among african american men who have sex with men in the young men's survey, los angeles, 1999–2000. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:39–52. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.39.23613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Meyer I, Aranda F, Russell S, Hughes T, Birkett M, Mustanski B. Mental health and suicidality among racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, Shiu C, Loosier PS, Dittus P, Michael Waldmiller J. A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31:273–309. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When black + lesbian + woman ≠ black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Huang J, Brooks K, Black A, Burkholder G. Triple jeopardy and beyond: Multiple minority stress and resilience among black lesbians. J Lesbian Stud. 2003;7:87–108. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell ER, Pines HA, Robbie E, Coleman L, Murphy RD, Hess KL, Gorbach PM. Use of the location-based social networking application grindr as a recruitment tool in rectal microbicide development research. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1816–1820. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0277-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Prevalence and awareness of hiv infection among men who have sex with men --- 21 cities, united states, 2008. MMWR; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Compendium of evidence-based hiv prevention interventions. 2013a Retrieved 10/07/2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/index.html.

- CDC. Hiv surveillance report, 2011. Vol. 23. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. A brief quality assessment of the nhis sexual orientation data. Hyattsville, MD: Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014a. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Hiv among youth. Washington, DC: 2014b. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk_youth_fact_sheet_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Ayala G. Sexual orientation and sexual behavior among latino and asian americans: Implications for unfair treatment and psychological distress. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47:451–459. doi: 10.1080/00224490903100579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Austin SB, Schuster MA. The health and health care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Annual Review of Public Health. 31:457–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64:170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JF. Biracial-bisexual individuals: Identity coming of age. International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies. 2000;5:221–253. [Google Scholar]

- Conley CL. Learning about a child's gay or lesbian sexual orientation: Parental concerns about societal rejection, loss of loved ones, and child well being. Vol. 58. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, McIsaac C. Romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Underwood MK, Rosen LH, editors. Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 180–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation : Design & analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally College Pub. Co; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;14:538–554. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and ptsd among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1462–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory. 2008;9:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;13:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Code of federal regulations, title 45 public welfare, part 46 protection of human subjects. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html. [PubMed]

- Diamond LM. The desire disorder in research on sexual orientation in women: Contributions of dynamical systems theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Savin Williams RC, Dube EM. Sex, dating, passionate friendships, and romance: Intimate peer relations among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 175–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Johnson JK, Viken RJ, Rose RJ. Testing between-family associations in within-family comparisons. Psychological Science. 2000;11:409–413. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher J. I'm your handyman: A history of reparative therapies. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;36:19–42. doi: 10.1300/J082v36n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1389–1398. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr WM, Philip NM, Justman J. Letting hiv transform academia — embracing implementation science. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Eastwick PW, Matthews J. Speed-dating as an invaluable tool for studying romantic attraction: A methodological primer. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Mustanski B. Reducing health disparities and enhancing the responsible conduct of research involving lgbt youth. Hastings Center Report, In Press. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hast.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc E, Stall R. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:1481–1494. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and hiv risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Harper GW. Not all adolescents are the same: Addressing the unique needs of gay and bisexual male youth. Adolescent Medicine. 2003;14:595–611. doi: 10.1016/S1041349903500470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Donenberg DR. Hiv prevention with young men who have sex with men: Parents know and parents matter; it's time to develop family-based programs for this vulnerable population. Journal of Adolescent Health, under review. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Donenberg G. Parents know and parents matter; is it time to develop family-based hiv prevention programs for young men who have sex with men? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GJ, Andrews R, Kuper L, Mustanski B. Intimacy, monogamy, and condom problems drive unprotected sex among young men in serious relationships with other men: A mixed methods dyadic study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014:73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37:527–537. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanin JE, Parsons JT. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming-out process among gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Sex Research. 2006a;43:115–121. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanin JE, Parsons JT. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming-out process among lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Sex Research. 2006b;43:115–121. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW. Sex isn't that simple: Culture and context in hiv prevention interventions for gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Psychologist. 2007a;62:806–813. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW. Sex isn't that simple: Culture and context in hiv prevention interventions for gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Psychologist. 2007b;62:803–819. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma "get under the skin"? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:S21–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Link BG. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2014;103:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk ET, Matrisian LM, Nelson WG, Dorfman GS, Stevens L, Kwok J Translational Research Working, G. The translational research working group developmental pathways: Introduction and overview. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:5664–5671. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RB, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Unprotected sex and hiv risk taking among young gay men within boyfriend relationships. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:314–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Norton AT, Allen TJ, Sims CL. Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a us probability sample. Sex Res Social Policy. 2010;7:176–200. doi: 10.1007/s13178-010-0017-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Egan JE, Coulter RW, Friedman MR, Stall R. Raising sexual minority youths' health levels by incorporating resiliencies into health promotion efforts. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:206–210. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo MA, Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Johnson AK, Mustanski B, Garofalo R. The mypeeps randomized controlled trial: A pilot of preliminary efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of a group-level, hiv risk reduction intervention for young men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0347-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Fowler B, Kibe J, McCoy R, Pike E, Calabria M, Adimora A. Healthmpowerment.Org: Development of a theory-based hiv/sti website for young black msm. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23:1–12. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway IW, Rice E, Gibbs J, Winetrobe H, Dunlap S, Rhoades H. Acceptability of smartphone application-based hiv prevention among young men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0671-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of, M. Ethical conduct of clinical research involving children. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people : Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadwin-Cakmak LA, Pingel ES, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA. Coming out to dad: Young gay and bisexual men's experiences disclosing same-sex attraction to their fathers. American Journal of Men's Health. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1557988314539993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil OB, Harper GW, Fernandez MI. Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay-bisexual-questioning (gbq) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0014795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Redding CA, DiClemente RJ, Mustanski BS, Dodge B, Sheeran P, Fishbein M. A network-individual-resource model for hiv prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:204–221. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Kinchen S, Chyen D, Harris WA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12--youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, united states, 2001–2009. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2011;60:1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Hops H, Redding CA, Reis HT, Rothman AJ, Simpson JA. A framework for incorporating dyads in models of hiv-prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9802-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuroghlian AS, Shtasel D, Bassuk EL. Out on the street: A public health and policy agenda for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:66–72. doi: 10.1037/h0098852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns LM, Kwon S, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Phillips G, Mustanski BS., 2nd Evaluation of respondent-driven sampling in a study of urban young men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9897-0. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSala MC. Parental influence, gay youths, and safer sex. Health and Social Work. 2007;32:49–55. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Katz-Wise SL, Calzo JP. The unjustified doubt of add health studies on the health disparities of non-heterosexual adolescents: Comment on savin-williams and joyner (2014) Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:1023–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal K, Greene GJ, Rivera Z, Mustanski B. “The best is always yet to come”: Relationship milestones and processes among same-sex couples in emerging adulthood. under review. [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar D, Valleroy L, Karon J, Lemp G, Janssen R. The young men's survey: Methods for estimating hiv seroprevalence and risk factors among young men who have sex with men. Public Health Reports. 1996;(111 Suppl 1):138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Bigelow L, Dehaan S, Mustanski BS. Sexual health information seeking online: A mixed-methods study among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young people. Health Education and Behavior. 2012;39:276–289. doi: 10.1177/1090198111401384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Morse JQ. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Identity, stress, and resilience in lesbians, gay men, and bisexauls of color. The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38:442–454. doi: 10.1177/0011000009351601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minority health and health disparities research and education act of 2000. 2000:S.1880. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Raudenbush SW. Tests for linkage of multiple cohorts in an accelerated longitudinal design. Psychological Methods. 2000;5:44–63. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with lgbt adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]