Abstract

The purpose of this project was to examine group- and individual-level responses by struggling adolescents readers (6th – 8th grades; N = 155) to three different modalities of the same reading program, Reading Achievement Multi-Component Program (RAMP-UP). The three modalities differ in the combination of reading components (phonological decoding, spelling, fluency, comprehension) that are taught and their organization. Latent change scores were used to examine changes in phonological decoding, fluency, and comprehension for each modality at the group level. In addition, individual students were classified as gainers versus non-gainers (a reading level increase of a year or more vs. less than one year) so that characteristics of gainers and differential sensitivity to instructional modality could be investigated. Findings from both group and individual analyses indicated that reading outcomes were related to modalities of reading instruction. Furthermore, differences in reading gains were seen between students who began treatment with higher reading scores than those with lower reading scores; dependent on modality of treatment. Results, examining group and individual analyses similarities and differences, and the effect the different modalities have on reading outcomes for older struggling readers will be discussed.

Keywords: Adolescents, reading, reading program design, Latent Change Score, individual gains

When considering what might be effective for adolescents at-risk for and with reading disabilities (hereafter referred to as struggling readers)there is a critical need to understand how they develop reading skills and the factors that impact success in learning to read at this age level (Calhoon, 2005; Calhoon, Sandow, & Hunter, 2010; Calhoon, 2013). Older struggling readers fall into a wide range of developmental levels, presenting a unique set of circumstances not found in younger more homogeneous beginning readers (Biancarosa & Snow, 2004). These struggling adolescents readers generally belong to one of two categories, those provided with little or poor early reading instruction or those possibly provided with good early reading instruction, yet for unknown reasons were unable to acquire reading skills (Roberts, Torgesen, Boardman, & Sammacca, 2008). Additionally within these two categories, adolescent struggling readers are extremely heterogeneous and complex in their remediation needs (Nation, Snowling, & Clarke, 2007; Torgesen et al., 2007).

Decades of research on the development of effective early literacy programs for beginning readers (Kindergarten through 3rd grade) have begun to help determine which reading components (e.g., phonological decoding, spelling, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, writing activities) need to be taught, and also how best to combine and organize these components in reading lessons to optimize the students’ response to instruction (i.e., Chard & Osborn, 1999; Ehri, 2000; Fletcher, Denton, Fuchs, & Vaughn, 2005; Juel & Roper/Schneider, 1985; Mathes, Howard, Allen, & Fuchs, 1998; National Reading Panel, 2000). Unfortunately, less has been learned to date about effectively organizing instructional components for adolescent struggling readers (Calhoon, 2006).

A recent meta-analysis of 85 studies with struggling readers in preschool through 7th grades suggests that the optimal type or modality of reading intervention may vary with grade level (Suggate, 2010). Phonics interventions produced greater effect sizes for kindergarten and 1st grade students, while mixed (phonics with comprehension) interventions and pure comprehension interventions yielded larger effects for older students. However, given the wide range of results from adolescent intervention studies (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Kazdan, 1999; Hasselbring & Goin, 2004; Lovett, Borden, DeLuca, Lacerenza, Benson, & Brackstone, 1994; Lovett, Lacerenza, Borden, Frijters, Steinbach, & De Palma, 2000; Lovett & Steinbach, 1997; Lovett, Steinbach, & Frijters, 2000; Mastropieri, Scruggs, Mohler, Beranek, Spencer, Boon, 2001; Vaughn et al., 2010, Vaughn et al., 2011a; Vaughn et al., 2011b), additional research on this issue is needed to provide a more complete picture that can inform the design and delivery of instruction for older struggling readers (Suggate, 2010).

In investigating efficacy of reading instruction, the analyses have typically focused on group-level effects. This approach provides valuable knowledge, but in some circumstances may potentially obscure gains occurring for individuals or subgroups. Given the wide range of remedial reading needs within the adolescent population, examining responses to different instructional programs at the individual level as well as for groups may thus be highly informative about the learning trajectories of adolescents who have struggled and not yet acquired normative literacy skills (Vaughn et al., 2010, Vaughn et al., 2011a; Vaughn et al., 2011b). Individual analyses have rarely been conducted in samples of struggling adolescent readers, however.

Goals

To better understand the needs of adolescent struggling readers, we sought to look in greater detail at the effects of modality differences, and to examine such effects at both the group and individual levels of analysis. The modalities being compared were three versions of an existing reading program whose efficacy has been examined in samples of struggling readers (Calhoon, 2005; Calhoon et al., 2010; Calhoon, 2013). The components of the program, the modality differences that were contrasted in previous analyses, and the findings to date are summarized in the following section.

The Reading Achievement Multi-Component Program (RAMP-UP)

The Reading Achievement Multi-Component Program (RAMP-UP; Calhoon, 2003) blends the cognitive strategy instruction, socio-cultural theory, and techniques of direct instruction to address the complex deficits of older struggling readers. First, RAMP-UP incorporates direct instruction with explicit cognitive strategy instruction. This approach is supported by findings from several major syntheses and a meta-analysis of research on models for instructing students with learning disabilities (Mastropieri, Scruggs, Bakken, & Whedon, 1996; Swanson, 1999a, 1999b, 2001; Swanson, Hoyskyn, & Lee, 1999; Talbott, Lloyd, & Tankersley, 1994). Cognitive strategy instruction relies on principles adapted from social learning and cognitive theories (Bandura, 1986; Meichenbaum, 1977); common features are strategy steps, modeling, verbalization, reflective thinking, and self-regulation (Vaughn & Bos, 2012). Other instructional techniques that have been shown to be effective with adolescent struggling readers are also used in RAMP-UP, such as directed questioning and responses, guided practice, explicit and direct instruction in phonological skills, extended practice opportunities with feedback, and breaking down tasks into component parts (Swanson, 1999b, 2001; Swanson & Hoskyns, 1998; Vaughn et al., 2000).

Second, based on principles of sociocultural theories, RAMP-UP uses reciprocal peer-tutoring, thereby providing an interactive social setting that allows students to integrate existing and new knowledge by negotiating with one another through the use of cognitive strategies that foster, monitor, and maintain understanding (Dole, Duffy, Roehler, & Pearson, 1991). The use of reciprocal peer-mediated instruction increases the kinds of social interchanges that have been associated with higher levels of academic engagement through active engagement in frequent, thoughtful reading for understanding (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002).

A fundamental design feature of RAMP-UP is its use of separate, stand-alone instructional modules for key reading components (phonological decoding, spelling, fluency, comprehension). These modules can be combined create different modalities, permitting a specific emphasis or dosage of instruction to be placed on one or more of the component(s) while ensuring standardization of implementation for each component. The modular design of RAMP-UP allows multiple modalities to be created from a single program, so that valid comparisons between the different modalities can be made with regard to their efficacy in strengthening reading proficiency of adolescent struggling readers. For additional information about RAMP-UP see Calhoon (2005), Calhoon et al. (2010), and Calhoon (2013).

To date, three modalities have been created from the core RAMP-UP program: Alternating, Integrated, and Additive. Table 1 provides a comparison of the instructional components and scheduling for the three organizational structures, each based on different assumptions about the needs of struggling adolescent readers.

Table 1.

Modality organization of the reading components

| Alternating Modality | Instructional Time Per Component by Study

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Monday

|

Tuesday

|

Wednesday

|

Thursday

|

Friday

|

Study #1 |

| Comprehension | Decoding | Decoding | Decoding | Comprehension | 51 hrs decoding, 34 hrs comprehension Study #2 58 hrs decoding, 39 hrs comprehension |

|

| |||||

| Integrated Modality | |||||

|

Monday

|

Tuesday

|

Wednesday

|

Thursday

|

Friday

|

Study #2 |

| Comprehension | Decoding + Fluency + Spelling |

Decoding + Fluency + Spelling |

Comprehension | Decoding + Fluency + Spelling |

37 hrs decoding, 13 hrs spelling, 8 hrs fluency, 39 hrs comprehension. Study #3 35 hrs decoding, 5 hrs spelling, 8 hrs fluency, 24 hrs comprehension |

|

| |||||

| Additive Modaltiy | |||||

|

1st- 7 weeks

|

2nd- 7 weeks

|

3rd- 7 weeks

|

4th-5–7 weeks

|

Study #2 | |

| Decoding | Decoding + Spelling | Decoding + Spelling + Fluency + spelling |

Comprehension + Spelling +Fluency |

63 hrs decoding, 16 hrs spelling, 6 hrs fluency, 12 hrs comprehension Study # 3 48 hrs decoding, 6 hrs spelling, 5 hrs fluency, 13 hrs comprehension |

|

The Alternating modality uses only two of the available reading components, phonological decoding and comprehension. This modality is based on research showing that most adolescent struggling readers appear to have a low-level core linguistic impairment in processing the sound structure (phonology) of language (Curtis, 2004; Curtis & Longo, 1999; Ehri, 1992; Hock et al., 2009; Stanovich & Siegel, 1994) leading to deficits concentrated in the areas of word identification and phonological decoding (Fletcher, et al., 1994; Hock et al., 2009; Savage, 2006). As shown in Table 1, phonological decoding instruction is provided separately for three days (e.g., Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays) and comprehension instruction occurs on two other days (e.g., Mondays and Fridays).

The Integrated modality expands the Alternating organization by combining spelling and fluency instruction with phonological decoding instruction, while continuing to alternate these with comprehension instruction. Spelling instruction was added to RAMP-UP because of its strong relationship to measures of pseudoword reading, word identification and vocabulary (Swanson, Trainin, Necoechea, & Hammill, 2003). Particularly instruction focused on words of similar patterns and structures as opposed to grouping words based on similar spellings (Bear & Templeton, 1998; Templeton, 1983). Fluency activities were added to provide practice and improvement of passage reading (Carnine, Silbert, & Kameenui, 1997), aiding in the development of a large inventory of quickly identifiable words (Dowhower, 1994). As shown in Table 1, phonological decoding, spelling, and fluency are taught for three consecutive days and comprehension for the other two days.

The Additive modality is based on the theory of LeBerge and Samuels (1974), which posits that reading is hierarchical in nature (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974; Reynolds, 2000; Samuels & Kamil, 1984) and that attaining automaticity of the lower-level components (consonants, vowels, syllables, grammatical endings, meaningful parts, and the spelling units that represent them) allows attention and cognitive effort to be allocated to acquiring higher level components (fluency and comprehension). Hence, the Additive modality breaks the instructional schedule into segments and introduces components sequentially, as illustrated in Table 1. Phonological decoding instruction is the sole component taught for the first seven weeks; spelling and phonological decoding instruction occurs for the second seven weeks; fluency instruction is added for the third seven weeks; finally, phonological decoding instruction is dropped and comprehension instruction is added for the remainder of the instructional period.

Three empirical investigations of efficacy and modality differences have been conducted to date. The central findings of all three studies will be summarized here (For a more in depth description of each study see Calhoon, 2005, Calhoon, 2010 and Calhoon, 2013). In the first study (Calhoon, 2005); the Alternating modality was compared to a widely used adolescent reading program. Participants were 38 6th and 7th grade struggling readers. The Alternating modality of RAMP-UP produced standard score gains of 6.6 to 8.9 for decoding and comprehension skills (pre-test standard scores ranged from 78.88 to 89.27; posttest scores ranged from 80.16 to 98.22), which were significantly greater than the control program, (F(1,37) ≥ 7.02, η ≥ .94). Neither program, however, promoted significant gains in fluency.

The second study (Calhoon, 2010), implemented with 90 6th, 7th, and 8th grade students with reading disabilities compared the Alternating, Integrated and Additive modalities. Overall, each modality produced significant standard score increases in decoding, fluency, and comprehension, but not spelling (pre-test standard scores ranged from 67.48 to 83.41; posttest scores ranged from 77.07 to 94.45). Comparisons between modalities showed the Additive program produced significantly larger gains than either the Alternating and Integrated modalities for word identification (9.0 vs. 3.5 and 2.7, respectively), word attack (14. 7 vs. 9.3 and 9.9) and spelling (3.2 vs. −0.7 and 0.7). With respect to oral passage reading fluency, the Additive and Integrated modalities significantly outperformed the Alternating modality (gains of 32.8 and 31.0 vs. 25.6 words correct per minute, respectively), while all three gained similarly in silent reading fluency (2.1 to 4.6 standard score points). On the Gray Silent Reading Test, a significantly larger increase favored the Additive condition (20.8) over the Integrated (9.6), with an intermediate effect for the Alternating modality (12.6).

A third study (Calhoon, 2013) was conducted with 47 6th grade students with and at-risk for reading disabilities comparing only the Integrated and Additive modalities. Both versions of RAMP-UP produced significant gains of comparable size (pre-test standard scores ranged from 72.17 to 88.70; posttest scores ranged from 82.26 to 96.95) in word identification (6.5 and 6.4, respectively), word decoding (8.3 and 10.3), spelling (3.1 and 3.0), oral reading fluency (18. 3 vs. 18.3), silent reading fluency (5.3 vs. 4.5), and passage comprehension (8.2 vs. 9.1). The only statistically significant (p < .01) difference found was for the Gray Silent Reading test (10.1 vs. 8.7), favoring the Additive modality.

Comparability across studies

Combining the student demographic databases from the three studies yielded a sample of 155 struggling middle school (6th through 8th grades) readers. A description of these students’ backgrounds is provided in Table 2 for each instructional modality. Chi-square analyses indicated students across the three modalities did not differ significantly (p < .05) in gender, ethnicity, and grade level, One-way ANOVAs on age and IQ identified no significant differences among the subgroups.

Table 2.

Student Demographics

| Variable | Alternating N = 47 |

Integrated N = 55 |

Additive N = 53 |

F | χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) | |||

| Age in Yearsa | 12.06 (.88) | 12.05 (.80) | 11.99 (.78) | 1.04 | ||||

| IQb | 91.45 (12.38) | 91.2 (12.50) | 95.16 (10.93) | 1.70 | ||||

| Genderc | 1.30 | |||||||

| Female | 17 (36.2) | 26 (47.3) | 23 (43.4) | |||||

| Male | 30 (63.8) | 29 (52.7) | 30 (56.6) | |||||

| Ethnicity d | 4.56 | |||||||

| Hispanic-American | 15 (31.9) | 25 (45.5) | 18 (24.0) | |||||

| Caucasian | 18 (38.3) | 15 (27.3) | 15 (28.3) | |||||

| African-American | 9 (19.1) | 12 (21.8) | 15 (28.3) | |||||

| Other | 5 (10.6) | 3 (5.5) | 5 (9.4) | |||||

| Gradee | 3.06 | |||||||

| Sixth Grade | 31 (66.0) | 39 (70.0) | 40 (75.5) | |||||

| Seventh Grade | 12 (25.5) | 8 (14.5) | 8 (15.1) | |||||

| Eighth Grade | 4 (8.5) | 8 (14.5) | 5 (9.4) | |||||

Note:

df = (1,3);

df =(1,3);

df=(1,2);

df=(1,5);

df=(1,4);

df =(1,2);

df=(1,4)

Training and fidelity for each study were implemented similarly for each of the four reading components. To insure fidelity of treatment, individual fidelity checklists were developed for each modality, consisting of statements capturing the essential elements of implementation and instruction. Fidelity (percentage of elements that were delivered with fidelity) ranged from 90.3 to 98.7 (M = 94.5) for the Alternating modality in Study 1; from 86.8 to 94.5 (M = 91.20) for the Alternating modality, from 92.5 to 95.2 (M = 93.8) for the Integrated modality, and from 91.6 to 94.2 (M = 92.9) for the Additive modality in Study 2; and from 84.0 to 98.0 (M = 91.33) for the Additive modality and from 88.0 to 98.0 (M = 92.6) for the Integrated modality in Study 3. It is therefore; reasonable to make comparisons based on fidelity and demographic data from these studies.

Therefore, the purpose of the current analyses was to synthesize the findings from the foregoing three modality studies with adolescent struggling readers, and to examine the outcomes at both the group and individual level to determine whether differences are evident among modalities.

Methods

Participants

Participants for Studies 1 and 2 were first selected by school administrators and special education language arts teachers based on: (a) having an Individual Education Program (IEP) goal or goals in reading; (b) currently receiving special education language arts in a self-contained or resource classroom; (c) having a history of reading difficulties; (d) having an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) score of 75 or above; and (e) currently not enrolled in an English as a Second Language class or receiving support from ESL personnel. The same criteria were used for Study 3, except that students at-risk for reading difficulties were also included, and these students did not have to meet criteria (a) and (b).

Eligibility was also based on the student’s reading grade level, which was estimated from the combined average of two subtests (Letter Word Identification ; Word Attack) of the Woodcock Johnson Tests of Achievement-III (WCJ-III; Woodcock, McGrew & Mather, 2001) along with the Comprehension subtest of the Gray Silent Reading Test (GRAY; Wiederholt & Blalock, 2000). Reading level on these tests was required to be 3.5 or lower for Studies 1 and 2, and 4.0 or lower for Study 3.

Measures

In all, eight reading measures were used, but two of the tests were not given in all three studies, as noted below. Each student was tested individually in a single session that occurred within one week of the beginning and end of the intervention period.

Decoding

The WCJ-III Letter Word Identification (LWID) and Word Attack (WA) subtests were given to measure decoding. For LWID students are asked to identify isolated letters and words correctly; test-retest reliability is .95. WA requires students to apply phonic and structural analysis skills to nonsense words; test-retest reliability is .85.

Spelling

WJ-III Spelling (SP) subtest was used to assess spelling-to-dictation by requiring the students to write orally-presented words of increasing difficulty. Test-retest reliability exceeds .95.

Fluency

The number of words in grade level connected text that the student reads correctly per minute was assessed with AIMSweb (Pearson Assessment, 2010) progress monitoring Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) passages. Alternate form reliability for ORF has been found to range from .81 to .91, and concurrent validity across a broad range of measures to range from .71 to .92 (Shinn & Shinn, 2002). The Reading Fluency (RF) subtest of the WCJ-III (RF) requires the student to read sentences silently and judge whether each is a true or false statement; test-retest reliability exceeds .87.

Reading Comprehension

The WCJ-III Passage Comprehension (PC) task assesses understanding of brief passages using a cloze procedure; test-retest reliability exceeds 0.91. The Gray Silent Reading Comprehension Test (GRAY) has students silently read passages and answer multiple choice questions. Coeffient alphas across 12 age intervals are greater than 0.90. The PC was given only in Study 2, and the GRAY was not administered in Study 1.

Results

The purpose of this study was to conduct an integrative data analysis across three studies that explored differences among RAMP-UP modalities implemented with 6th through 8th grade struggling readers from both a group and an individual level perspective. Results of latent change analyses to examine treatment effects at the group level will first be reported. A supplementary exploration of gains by individuals through comparisons between high- and low-gainer subgroups will then be described.

Preliminary Analyses

Prior to the main analyses it was important to examine the extent to which modality differences existed on the pre-intervention assessments, as well the extent to which data were missing. When data from the three studies were concatenated, a series of ANOVAs were run to test for initial fall differences across the conditions, and a Linear Step-Up (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) was applied to control for the false discovery rate. No statistically significant differences were detected across modalities for LWID [F(3,153) = 1.63, p = .18], WA [F(3,153) = 2.07, p = .11], PC [F(3,153) = 2.21, p = .10], ORF passages [F(3,153) = 0.31, p = .82], or the GRAY [F(3,153) = 0.84, p = .43]. Although RF appeared to be statistically significant [F(3,153) = 2.73, p = .046], once the linear step-up procedure was applied, the effect was no longer significant.

The overall percentage of missing data was 8.5%, but when disaggregated across individual measures, the missing data was restricted to the pretest administrations of the GRAY (13.4%) and PC (64.2%), as well as the posttest administration of the GRAY (13.4%). Missing data could be attributed to a missing-by-design pattern, due to the fact that the fall and spring assessments of the GRAY were not administered in Study 1 and the fall assessment of the PC was not given in Study 2. In such an instance multiple imputations of the data is appropriate (Enders, 2010). To correct for potential bias in the latent change score estimation of the parameters, a multiple imputation was conducted using the Multiple Imputation procedure in SAS 9.2 using Markov Chain Monte Carlo estimation with 10 imputations, and with the minimum and maximum values for the sample distribution for each variable as constraints.

Descriptive statistics for the original and imputed data are reported in Table 3. For the three variables that presented missing data the maximum standardized difference between the original and imputed scores was d = 0.08 for the GRAY scores in the spring. At the fall administration, students had nearly identical mean W-scores on LWID and RF tasks (i.e., 476.2), with a higher average performance on WA (478) and PC (482). From fall to spring, students made gains across all individual measures. The bivariate correlations, shown in Table 3, ranged from r = .23 between fall PC and LWID to r = .84 between fall and spring ORF. The strong correlation between fall and spring ORF was an indication of high stability in student performance over time, as was the r = .73 estimate for RF. Moderate performance stability existed for the GRAY (r = .65) and LWID (r = .61), with relatively lower stability observed for WA (r = .53), and PC (r = .43). With strong stability in student’s performance on the ORF and RF assessments, it was expected that there would be less individual differences in change from the fall to spring because the large correlation was partly an indication of a relatively constant rank order in scores. Conversely, with the lower correlations on WA and PC, this was evidence that students who obtained lower scores on the two measures at the fall did not necessarily have lower scores at the spring, and shifted their position in rank ordering of students over time.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Original and Imputed Data.

| Variables | Fall LWID |

Fall RF |

Fall ORF |

Fall Gray |

Fall PC |

Fall WA |

Spring LWID |

Spring RF |

Spring ORF |

Spring Gray |

Spring PC |

Spring WA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall LWID | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Fall RF | 0.50 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Fall ORF | 0.49 | 0.67 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Fall GSR | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Fall PC | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Fall WA | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Spring LWID | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 1.00 | |||||

| Spring RF | 0.45 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||||

| Spring ORF | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |||

| Spring GSR | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.60 | 0.14 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||

| Spring PC | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 1.00 | |

| Spring WA | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Original Data: Mean (SD) | 476.24 (20.38) | 476.20 (16.56) | 67.08 (26.38) | 14.47 (8.04) | 481.94 (12.82) | 477.64 (15.46) | 494.36 (19.03) | 488.58 (19.46) | 90.60 (31.06) | 24.89 (11.64) | 496.71 (15.81) | 499.15 (12.80) |

| Imputed Data: Mean (SD) | 476.24 (20.38) | 476.2 (16.56) | 67.08 (26.38) | 14.22 (7.12) | 482.5 (11.31) | 477.64 (15.46) | 494.36 (19.03) | 488.58 (19.46) | 90.6(31.06) | 23.97(10.73) | 496.71 (15.81) | 499.15 (12.80) |

Note: Italics are test-retest correlations

Latent Change Scores Analyses (LCS)

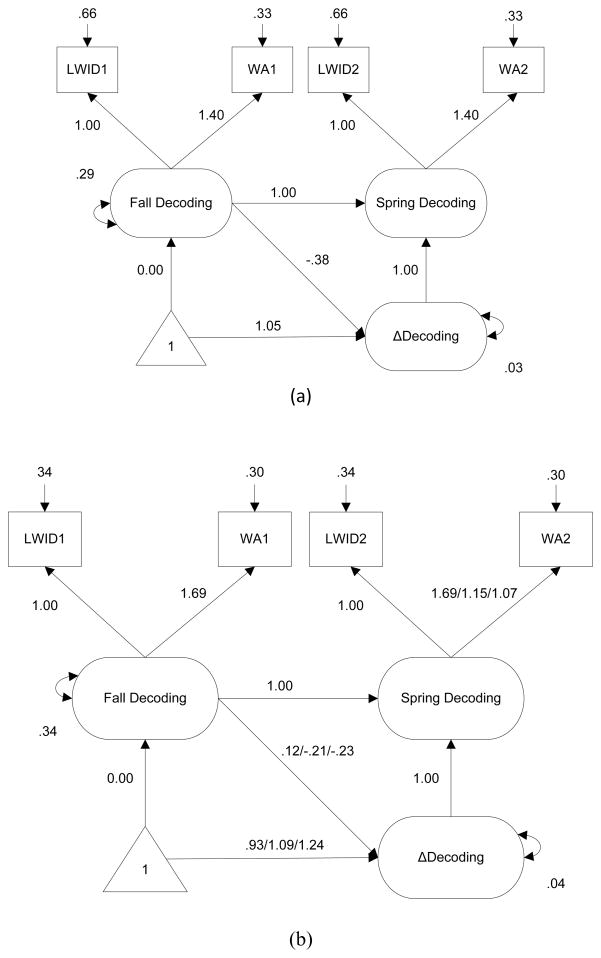

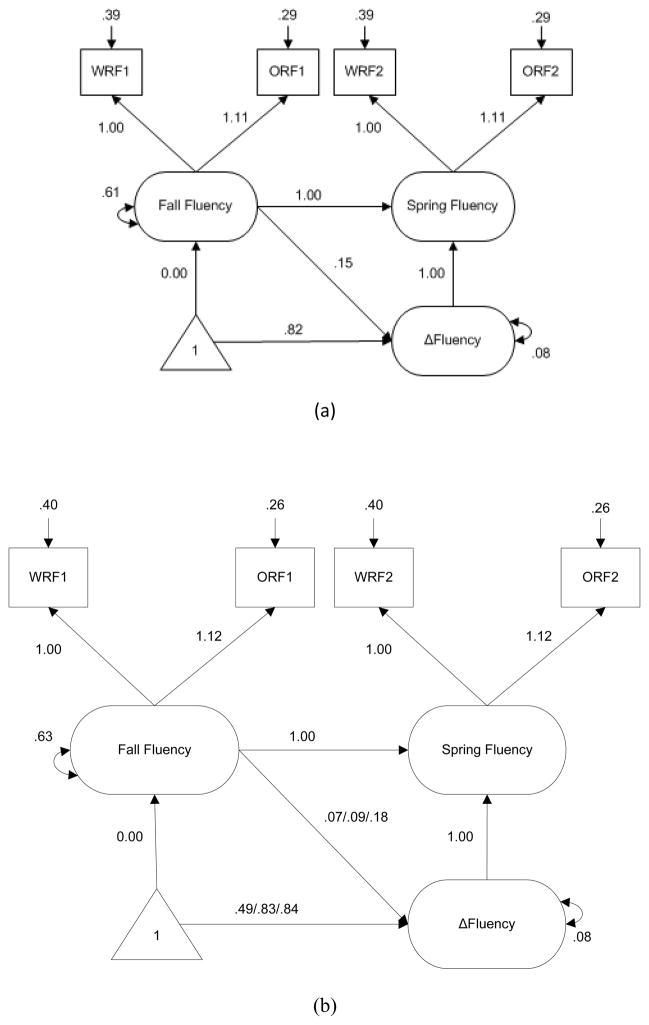

It is well known that individual, observed measures are subject to measurement error; thus, latent variables were created to represent decoding (LWID and WA), fluency (RF and ORF), and reading comprehension (PC and GRAY). These linear composites were fit using confirmatory factor analysis, and utilized in the latent change score analysis. The reporting of the LCS results is broken into three sections; first, a description of the analytic methods; second, model results for each outcome (Figures 2a, 3a, 4a), which estimate the path coefficients and factor means averaged across all treatment conditions; and multiple group LCS models (Figures 2b, 3b, 4b) to estimate differences among the treatment conditions.

Figure 2.

Decoding measurement models results for (a) latent change score and (b final multiple group latent change score.

Note. Freed group estimates are reported as Alternating/Integrated/Additive.

Figure 3.

Fluency measurement models results for (a) latent change score and (b) final multiple group latent change score.

Note. Freed group estimates are reported as Alternating/Integrated/Additive.

Figure 4.

Reading Comprehension measurement models results for (a) latent change score and (b) final multiple group latent change score.

Note. Freed group estimates are reported as Alternating/Integrated/Additive.

LCS Methods

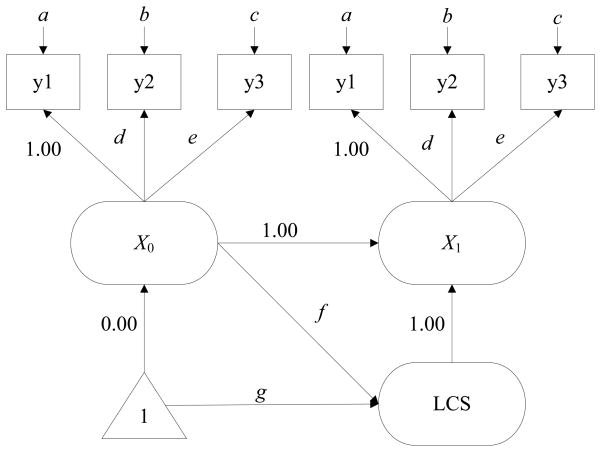

To answer our first research question, which concerns the relationship between changes in reading skills and differences between groups that received different modalities of RAMP-UP in intervention, a series of multiple group latent change score (LCS) analyses (McArdle, 2001) were conducted with W-scores on the WCJ-III measures, and the raw score of the GRAY. Although largely applied in cognitive development and aging research, the use of LCS in literacy research may have high utility as it combines aspects of longitudinal modeling and causal relationships among multivariate constructs. LCS models may be viewed as a hybrid between traditional latent growth curve models and cross-lagged regression, whereby they capture the change that occurs between latent difference scores at multiple time points. Change scores in observed measures are typically calculated by taking the difference between an individual’s score at a later point in time from their baseline score. This is often expressed as:

| (1) |

representing that individual i has changed between the baseline (X0) and a later assessment (X1), accounting for measurement error at each time point (e1 and e0). Just as raw difference scores may be calculated with equation 1, a latent change score (LCS) follows the same logic by taking the difference between two latent variables. Because latent constructs model the common variance across the observed indicators, it is assumed to be without error; thus, a LCS could be written as:

| (2) |

where the change score captures the reliable components of equation 1 (King et al., 2006). In this manner, one is able to view change as a function of latent, rather than raw, differences.

Specification of a basic LCS measurement model for an outcome is displayed in Figure 1 to facilitate a discussion of the assumptions and constraints of the model. For clarity we present a simplistic model rather than one with symbols traditionally associated with a measurement model for means, variances, and path coefficients (see McArdle, 2001 for further information). At first glance, Figure 1 appears to be nothing more than a typical structural equation model that estimates the effect of X0 on X1, X0 on LCS, and LCS on X1; however, as a change score model, there are several differences are worth mentioning. In this example, we assume that a construct, X, is measured over at least two time-points: baseline (i.e., pretest; X0) and future (i.e., posttest; X1) assessment, and that at each time point, the construct is measured by the same observed variables (i.e., y1–y3). The error variances in the model (a, b, and c) are constrained to be equal for each measure across the pretest and posttest measurement occasions. Similarly, the loadings for y2 and y3 (d and e, respectively) are constrained to be equal over time. In both cases, these invariances are specified so that the estimated LCS is a function of actual change, and unrelated to differences in how the observed measures describe the latent factor over time.

Figure 1.

Sample latent change model denoting constrained error scores (a,b,c) for each observed measures (y11, y12, y13, y21, y22, y23) across baseline (X0) and future measurement (X1), fixed loadings for model identification (y1), constrained loadings across time points for each measures (d,e), fixed intercept for X0, fixed autoregressive effect of X1 on X0, fixed autoregressive effect of the latent change score (LCS) on X1, estimated path coefficient for LCS on X0 (f), and estimated intercept for LCS (g).

Implicit to these constraints is that a formal test of configural and metric invariance has occurred; thus, an important first step in the estimation of the LCS is the extent to which the indicators are invariant over time. For model scaling, the loadings of y1 are fixed to 1.0, and for model identification in the LCS, the effects of X0 on X1, and LCS on X1 are also fixed to 1.0. Last, the intercept of X0 is constrained to 0.00. The two freed parameters in this model for estimation are the autoregressive effect of the pretest on change (f), and the mean LCS (g). When interpreting the path f, a negative value indicates that individuals with low latent pretest scores gained more than those with higher pretest scores, a value near 0 describes a pattern of constant change across the students, and a positive value describes fan-spread growth where those who have higher X0 ability scores had higher LCSs than those with lower X0 ability.

The scaling of the latent change score is an important consideration before fitting the LCS model to the data. Without scaling the scores over time, the resulting change score is not interpretable. In order to appropriately estimate the scores, the observed measures were converted to z-scores at the fall. Scaling occurred by taking the mean and variance for each raw score variable at the fall, and applying that distribution to the spring raw scores to create scaled z-scores for the spring which were sensitive to change. Because the raw scores were converted to a z-score, the results of the LCS reflect standardized unit change.

We explored basic LCS models for measures of decoding, fluency, and reading comprehension, as well estimating treatment effects for each latent construct. By implementing a multiple-group approach to the LCS models, it was possible to explore the extent to which means in the LCS varied across the three groups, as well as the invariance of the parameters (e.g., residual variances, effect of time 1 on the LCS). Across the three outcomes, an initial model was specified which constrained all parameters to be equal over the treatment groups, thereby allowing a test of complete invariance. This model was followed by revisions which incrementally relaxed particular constraints until adequate model fit was reached according to common fit indices. A difference in the chi-square for nested models was used, as were the root mean square error of approximate (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1992), comparative fit index (CFI, Bentler, 1990), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Bentler & Bonnett, 1980). CFI and TLI values greater than or equal to 0.95 and RMSEA up to .10 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996) are considered to be minimally sufficient criteria for acceptable model fit.

The first step of the LCS model building involved a test of longitudinal invariance of loadings and errors from the fall to spring. Resulting fit to the data for the base model was acceptable across multiple indices (see Table 4) for decoding [χ2(3) = 5.32, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .08 (95% CI = .00, .18)], fluency [χ2(2) = 2.58, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI = .00, .18)], and reading comprehension [χ2(2) = 4.61, CFI = .98, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .09 (95% CI = .00, .22)]. The decoding LCS results (Figure 2a) indicated that the mean change score across all individuals was 1.05 (p < .001), and that the autoregressive effect of fall decoding on the change score was negative (−.38). When considering the fluency LCS (Figure 3a), a small, and positive association was estimated between the latent fall score and change (.15), with an overall mean change of 0.82 from fall to spring. Reading comprehension demonstrated the largest mean gains for the latent change score (1.38; Figure 4a), with a small autoregressive effect of fall scores on the change score (.18).

Table 4.

Model fit indices for base model and multiple group invariance testing across outcomes

| Outcome | Model | Chi-square | df | BIC | RMSEA (95% Confidence) | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decoding | Base | 5.32 | 3 | 1269 | .08 (.00, .18) | 0.99 | 0.97 |

| Invariance | 249.06 | 32 | 4105 | .39 (.35, .44) | 0.01 | 0.33 | |

| Freed Regression | 213.93 | 30 | 4079 | .37 (.33, .42) | 0.01 | 0.39 | |

| Freed Intercepts | 140.51 | 29 | 4011 | .29 (.25, .34) | 0.39 | 0.62 | |

| Freed Posttest | 32.73 | 22 | 1259 | .10 (.00, .18) | 0.94 | 0.95 | |

| Fluency | Base | 2.58 | 2 | 1278 | .05 (.00, .18) | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Invariance | 96.56 | 31 | 1338 | .22 (.17, .27) | 0.82 | 0.90 | |

| Freed Regression | 52.42 | 27 | 1313 | .15 (.09, .20) | 0.93 | 0.95 | |

| Freed Intercepts | 28.03 | 25 | 1299 | .05 (.00, .14) | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| Reading Comp. | Base | 4.61 | 2 | 1243 | .09 (.00, .22) | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| Invariance | 167.78 | 28 | 1695 | .33 (.29, .38) | 0.27 | 0.53 | |

| Freed Regression | 161.11 | 25 | 1703 | .33 (.28, .39) | 0.30 | 0.49 | |

| Freed Intercepts | 68.4 | 25 | 1611 | .20 (.14, .27) | 0.77 | 0.84 | |

| Freed Pretest-Posttest | 29.84 | 18 | 1606 | .11 (.03, .19) | 0.95 | 0.94 |

Note. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index.

Treatment effects related to latent change

Differences in LCS among each of the modalities (Alternating, Integrated, Additive) were examined. For each of the outcomes, a model was tested which assumed the complete invariance of parameters across the three groups (i.e., pattern coefficients, means, regression effects). This model was compared to subsequent models which freed specific parameters within the model where it was believed that differences among the modalities would lie. Because it was expected that differences might exist in the relationship between the latent fall score and the change score, as well as in the mean latent change, these parameters were iteratively freed.

When considering the latent composite of decoding, the model testing complete invariance fit very poorly [χ2(32) = 249.06, CFI = .01, TLI = .33, RMSEA = .39 (95% CI = .35, .44)]. Subsequent models were run which freed the regression of the latent change score on the fall score (Table 4), as well as intercept value for the latent change score, and the pattern coefficient for Word Attack. The final model which incorporated these changes yielded acceptable fit to the data [χ2(22) = 32.73, CFI = .94, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .10 (95% CI = .00, .18)], and significantly differed from the baseline model (Δχ2(10) = 216, p < .001), indicating that the freed parameters across groups reflected significant between-group differences. Figure 2b highlights that the effect of fall decoding on the decoding change score was small and positive for students in the Alternating modality (.12), while it was small and negative for those in the Integrated (−.21) and Additive (−.22) groups. This indicated that students in the Alternating modality who had higher decoding ability in the fall tended to change more between the fall and spring. Conversely, students in the other two modalities demonstrated that those with lower decoding ability in the fall changed more. The mean latent change score in decoding, in standardized units (z units), for the three modalities were: .93 in the Alternating group, 1.09 in the Integrated group, and 1.24 in the Additive group.

Model fit for the specification of the invariance of fluency parameters across the modalities are also reported in Table 4. Based on the sequential process of fitting constrained and freed models, the model which freed the change score on fall regression and the mean change scores across groups fit significant better than the invariant model [Δχ2(6) = 68, p < .001]. Figure 3b shows that the relationship between fall fluency and the change score was near 0 for the Alternating (.07) and Integrated (.09) modalities, and stronger for the Integrated (.83) and Additive (.84) conditions than for the Alternating modality (.49).

Latent change for reading comprehension showed differences across the conditions in both the means, and the specific relations between fall and change score performance. The final model included freed regressions and means, as well as specific covariance’s within each time point, and variances of the fall composite (Figure 4b). This model fit significantly better to the better than the model of complete invariance [Δχ2(10) = 138, p < .001]. The mean change was strong across all three modalities, with the largest gains made by those in the Additive condition (1.66) followed by Alternating (1.39) and Integrated (1.17) groups. Moreover, the pattern of change suggested that much more fan-spread change was observed in the Alternating compared to the other modalities, indicating that students with higher reading comprehension in the fall made stronger gains over the year.

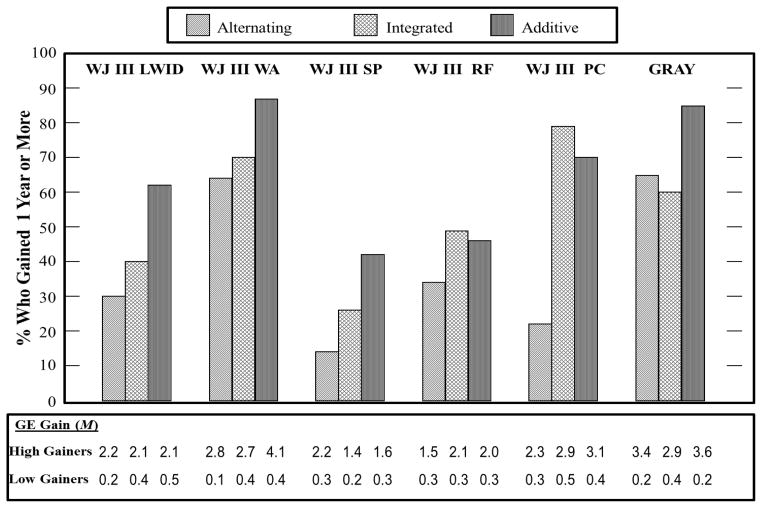

Individual student gains

To address our second research question which concerned the association between interventions and individual differences, we examined individual gains made by adolescent struggling readers after being provided one year of intensive reading instruction. Grade equivalent (GE) score differences from pre- to posttest were used to represent educationally meaningful changes in performance on the measures. Because ORF words correct per minute cannot be derived into GE scores, this measure was not used in the analysis. Individual students were classified as ‘high-gainers’ if their GE rose one full year or more from pretest to posttest and as a ‘low-gainers’ if the change in GE was less than a year. This cut point was based on the assumption that if provided with one year of instruction, a student who is not falling further behind should attain at least as much growth as a typically developing student would make in a year’s time.

GE scores were chosen as metric for representing gain at the individual level because of its transparency. GE’s are continuous interval-scaled scores that reflect, in years and months, the grade level at which a student achieves. For example, a student earning a 2.4 GE score on the RF subtest would be regarded as performing the same as a second grade student in the fourth month of the school year (i.e., November/December).

W scores, which are useful for tracking change were considered for this purpose, but not used because of their lack of transparency due to the ambiguity of interpretation, as spelled out in detail by Scarborough et al., (this issue). For instance, “an increase of 10 W units represents the individual’s ability to perform, with 75% success, tasks that he or she could previously perform with 50% success” (Jaffe, 2009; pg. 6). Hence, it is difficult to decide how much of an increase in W indicates satisfactory improvement by an adolescent. GE scores for the WJ-III tests are tied to the median ‘W-scores’ of the standardization

The percentage of high-gainers for each subtest by modality (Alternating, Integrated, Additive) is shown in Figure 5. Chi square tests of association showed the organization of the instructional components was associated with differences in the proportion of high-gainers across all measures (all phi = .22 to .48, χ2 (df = 2) > 7.5, p < .05) except for RF (phi = .13, p > .05). Pairwise comparisons between designs using chi-square tests further demonstrates for LWID (Additive > Alternating: 10.5475, p<.01; Additive > Integrated: 5.3535, p < .05), WA (Additive > Alternating: 7.2010, p < .01; Additive > Integrated: 9.864, p < .01), and GRAY (Additive > Integrated: 8.3453, p < .01; Additive > Alternating: 4.1126, p < .05), a similar pattern across the three subtests with the Additive modality producing significantly more high-gainers than the other modalities. For PC, the Additive and Integrated modalities produced the largest rates of high-gainers (Additive > Alternating: 9.0583, p < .01; Integrated > Alternating: 14.694, p < .01). Results for SP showed a significant difference in high-gainers between the Additive and Alternating modalities, however neither modality differed significantly from the Integrated condition (Additive > Alternating: 8.5703, p < .01; Additive > Integrated: 3.13, p > .05; Integrated > Alternating: 1.1433, p > .05).

Figure 5.

Percentage of High-Gainers (=> 1year) by organizational modality of components and reading subtests.

The Additive modality produced the highest percentage of high gainers on four of the six assessments (LWID [62%]; WA [87%]; SP [42%]; GRAY [85%]) and the largest mean gain in years of growth on two assessments (WA [4.1 years]; GRAY [3.6 years]). The Integrated modality had the highest percentage of high gainers on RF (49%) and PC (79%). However, for the Integrated modality, the students who were high gainers made comparable mean gains to students in the Additive modality on four assessments (LWID [Additive 2.1 years; Integrated 2.1 years]; SP [Additive 1.6 years; Integrated 1.4 years]; RF [Additive 2.1 years; Integrated 2.0 years], PC [Additive 3.1 years; Integrated 2.9 years]). The Alternating modality while producing the smallest percentage of high gainers on five of the six assessments, interestingly showed a higher mean gain in years of growth than the Integrated and Additive modalities for SP (Alternating [2.2 years]; Integrated [1.4 years]; Additive [1.6 years]) and a higher mean gain than the Integrated for the GRAY (Alternating [3.4 years]; Integrated [2.9 years]).

Discussion

There is a critical need to provide a research base to guide the development of effective reading programs for adolescents with RD. The goals of this study were twofold. First, we examined the effects, if any, of the modality of instruction using the same RAMP-UP program but systematically altering the organization, sequence, and duration of the reading components. Second, our aim was to address this matter at both the group and individual level of analysis. Results demonstrate that older struggling readers are sensitive to different organizational sequencing of the reading components, and to the amounts of time devoted to each reading component. This was evident in both the LCS group analysis and analyses of proficiency gains by individual students. In what follows we describe results separately for each of the key reading components that were analyzed: decoding (including word identification and word attack; fluency (both oral and silent text reading); comprehension; and spelling. In most instances results from the individual analysis coincided well with those from the multivariate group analyses, but there were some interesting patterns of were revealed from only one approach, as will be discussed.

Decoding

Findings from both the LCS analyses and examination of individual gains demonstrates that modality does matter for teaching decoding skills to adolescent struggling readers. In the LCS models the latent decoding factor was derived from test of word recognition and pseudoword decoding. Across all three modalities students in the sample made large, educationally meaningful gains. However the Additive modality produced the largest average gains (Alternating, .93; Integrated, 1.09; Additive, 1.24) for decoding.

A tantalizing finding from the LCS analysis was an indication of a learner by modality interaction. Students who began the treatment with higher decoding skills appeared to make greater gains in these skills when provided reading instruction with the Alternating modality. In contrast, students with weaker decoding skills at the outset appeared to make larger gains in these skills when provided reading instruction in either the Integrated or Additive modality, with the largest gains made by students in the Additive modality.

Results of the individual analyses showed the same pattern of student response in relation to modality when we examined the percentage of high gainers in each treatment group and compared the mean gain in reading level (grade equivalence) for the higher and lower gainers across modalities for the decoding measures. On LWID, 30%, 40% and 62% of the students across the modalities (Alternating, Integrated, and Additive, respectively) raised their grade levels by the equivalence of two or more years. For WA, 64% (Alternating) and 70% (Integrated) of students made such gains, while 87% of students receiving the Additive modality made gains that were twice as large. Taken together, the individual and group analyses indicate that the Additive modality is potentially most effect at strengthening decoding skills of adolescent struggling readers as in our sample.

These analyses also revealed the extreme disparity between the high and low gainers within each modality. The average change in reading level for low gainers ranged from .01 to .05 years, demonstrating that those students who did not succeed made almost no progress at all. Although our criterion for gain, an increase of 1 year in reading level, was made somewhat arbitrarily it has proved to distinguish quite well between student making progress and those failing to benefit from instruction.

Finally it bears noting that, regardless of modality, the percentage of students and years of growth was larger on the WA subtest than the LWID subtest. It would be expected that decoding of real words would advance at the same level as that of nonsense words but this was not observed. A similar finding was found with adult learners (Sabatini, 2002). One explanation might be that nonsense words follow more closely true phonetic rules, while real words, especially multisyllabic words found later on the LWID subtest vary too far from the phonetic rules. It could be hypothesized that these older students still need more intensive phonological decoding provided at even a much deeper level (i.e., stressed and unstressed syllables; changes in vowel sound in multisyllabic words) for a longer period of time for generalization to real words to take place.

Both the LCS and individual analyses indicated that the best modality for boosting decoding skills for struggling adolescent readers is the Additive modality. Although the LCS and individual analysis are totally consistent with each other, the LCS is more informative to researchers because of the statistical interpretations and effect size metrics, and the individual analyses are more beneficial for teachers and administrators because of ease of interpretation and language congruency with information presentation (i.e., grade equivalency gains) within school settings.

Fluency

For fluency, the LCS model demonstrated that students provided reading instruction in the Integrated (.83) and Additive (.84) modalities made larger gains than students in the Alternating (.49) modality. Again, as with decoding, the analyses of individual gains in reading levels showed a similar pattern of findings to the LCS analyses while providing a somewhat more informed picture. Slightly less than 50% of students made on average two years of growth in the Integrated and Additive modalities, while for the Alternating modality only 14% of the students increased on average one and half years. The mean average gain for low gainers for all three modalities (range 54% – 66%) represented only three months in grade equivalent terms, again showing the disparity between higher and lower gainers. It is known that increasing fluency for older struggling readers is difficult (Edmonds et al., 2009; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Kazdan, 1999; Olson, Wise, Johnson, & Ring, 1997; Mastropieri et al., 2001). However, it is encouraging that an average gain of two years was attained by the higher gainers in both the Integrated and Additive modalities for approximately half of these older struggling readers, large gains in fluency were achieved and the modality for acquiring these gains mattered.

Comprehension

The pattern of results from the LCS model indicated that students in all three modalities made large gains, and that students in the Additive modality classes made larger gains (1.66) than those who received the other two modalities (Alternating, 1.39; Integrated, 1.17). Noteworthy, LCS analyses suggested that there were learner by modality interactions similar to those seen for decoding. Students who started treatment with higher comprehension skills appeared to make greater gains in comprehension when provided the Alternating modality. In contrast, students with lower comprehension skills at the outset made larger gains in comprehension when provided with either the Integrated or Additive modality, again with the largest gains made by students in the Additive modality.

Individual gains for comprehension contributed to providing a more complete and complimentary picture of the group level results. For the WCJ-III PC test, the Integrated modality produced a somewhat higher percentage of high gainers (79%) than the Additive modality (70%), with high gainers in both these modalities making approximately three years of growth. In the Alternating modality, however, there were relatively few high gainers (22%) and their reading levels rose less sharply, on average. On the GRAY comprehension test, however, it was the Integrated modality that produced somewhat fewer high gainers, whose gains were slightly smaller, than the Additive and Alternating modalities..

The difference in modality effects between comprehension measures needs to be further explored in future research. One explanation could be test format. The WCJ-III PC subtest is a cloze format while the GRAY comprehension test is a question and answer format. The two measures may be tapping into different cognitive processes and may be influenced to different degrees by particular skills influencing comprehension’ (Cutting & Scarborough, 2006, p. 294). Noteworthy, however is that 60 to 85 percent of the high gainers in both the Additive and Integrated modalities made at least three or more years gain in comprehension skills on both comprehension measures.

As found for decoding and fluency, the disparity of gains made between the high and low gainers was quite large. The range of growth for the low gainers was only 2 to 5 months for all three modalities. The individual analyses were able to highlight the differences between those who benefited from instruction and those who failed to benefit. It is important to remember there is still a percentage of students’ not making adequate progress even with intensive instruction. How to instruct these low gainers is still a pivotal question program developers need to keep in mind.

Impressive and unexpected were the large gains made in comprehension by students in the Additive modality, insofar as they receive relatively few hours of explicit comprehension instruction (12–13 hr.) in comparison to the other modalities (24–39 hrs.). The theoretical underpinnings of the Additive modality are that reading is hierarchical and that automaticity of lower level skills (decoding, spelling) allows cognitive efforts to then be allocated to attaining higher level skills (fluency, comprehension; LaBerge & Samuels, 1974; Reynolds, 2000, Samuels & Kamil, 1984). Clearly, the changes brought about by other aspects of instruction (front loading of phonics instruction, followed by the addition of spelling instruction, followed by the addition of fluency instruction) laid the groundwork for comprehension gains, without having to supply a great deal of explicit comprehension instruction. These older struggling readers were able to master decoding, spelling, and fluency, before comprehension was even introduced into instruction, enabling them to more fully understand strategy instruction and achieve comprehension gains with very little explicit comprehension strategy instruction. These results strongly suggest that it may not be how many hours of instruction for each component that is important, but instead when those hours are incorporated into organization of instruction, that matters most.

Spelling

Spelling was examined only in analyses of growth by individual students. Consistent with results of the foregoing analyses for other aspects of literacy, the findings for spelling indicated that modality matters for the teaching of this skill also. While only 42% of students in the Additive modality were high gainers, it is impressive that the average gain of those who met the criterion was almost two years. Spelling is considered a more difficult skill than reading and requires a more comprehensive understanding of sound-symbol correspondences and orthographic representation (Ehri, 2000; Shankweiler & Lundquist, 1992). Gains in spelling ability correlate highly with gains in many linguistic abilities, including word-level reading and reading comprehension skills (Kelman & Apel, 2004; Masterson & Crede, 1999; Mehta, Foorman, Branum-Martin, & Taylor, 2005; Vellutino, Tunmer, Jaccard, & Chen 2007). Therefore, given the pattern of results in decoding and comprehension skills, it is not surprising that a higher percentage of students in the Additive modality also improved solidly in spelling.

Limitations

As with any research, limitations need to be noted. First, the use of grade equivalent scores as the metric for gains is not without controversy, although the complementary findings from the group and individual analyses suggest that this was not problematic. Second, not all reading measures were administered in all studies (GRAY not used in Study 1; WCJ-III Passage Comprehension only administered in spring for Study 2). This possibly created a difference in response rates for comprehension. Finally the sampling methods in the three studies varied slightly, and it would have been better if recruitment and inclusion criteria had been more consistent across studies.

Conclusions

Questions have sometimes been raised about the extent to which reading skills of struggling adolescents can be remediated and whether the money spent on such interventions is justified in light of the degree of benefit attained (Vaughn et al., 2010, Vaughn et al., 2011a; Vaughn et al., 2011b). Adolescents who have already gone through years of reading instruction and still lag behind their same age peers are a very heterogeneous group in their reading abilities. Through the use of both group and individual differences analysis we were able to gain a more complete and finely-tuned picture of how these struggling readers respond to treatment. The struggling readers in this study were multiple grade levels (three to seven years) behind their typically developing peers in reading ability. Results of both group and individual analyses indicate these older struggling readers can be remediated and for some, gains of two, three, four, or more years can be accomplished with only one year of instruction. While two to three years of gain for students who are four to six years behind by no means closes the achievement gap, these findings are encouraging in providing information on which modality of instruction closes the achievement gap best.

Most compelling from the current analyses are results directly investigating the differences between three modalities (Alternating, Integrated, Additive) of instruction. Outcomes showed clearly that modality of instruction can matter considerably for these older struggling readers. The differences in gains clearly demonstrate that the Additive modality, with its sequential addition of each component (isolated phonological decoding instruction, followed by addition of spelling instruction, followed by addition of fluency instruction, and finally the addition of comprehension instruction [see Table 1]) is potentially the best modality for remediating reading skills (decoding, spelling, fluency, comprehension) in older struggling readers, of the three approaches that were compared in this research. These students show that they are highly sensitivity to the scheduling of the components and the amounts of instructional time per component; this is an important finding for the development and refinement of reading programs for struggling adolescent readers. While more research still needs to be conducted in this area, this study lends credence to the different requirements this unique population of students may need in order to close the achievement gap in acquiring adequate reading skills.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Children’s Health and Human Development, R03HD048988 and P50HD52120; as well as in part by the Institute of Education Sciences’ Reading for Understanding Consortium via awards to Florida State University (R305F100005).

Contributor Information

Mary Beth Calhoon, Lehigh University.

Yaacov Petscher, Florida State University and the Florida Center for Reading.

References

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear DR, Templeton S. Explorations in developmental spelling: Foundations for learning and teaching phonics, spelling, and vocabulary. The Reading Teacher. 1998;52(3):222–242. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57(1):289–300. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2346101. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonnet DC. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Biancarosa G, Snow CE. Reading next: A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy. A report to the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research. 1992;21:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoon MB. Reading Achievement Multi-Component Program (RAMP-UP) Unpublished adolescent remedial reading program 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Calhoon MB. Effects of a peer-mediated phonological skill and reading comprehension program on reading skill acquisition of middle school students with reading disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2005;38:424–433. doi: 10.1177/00222194050380050501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoon MB. Rethinking adolescent literacy instruction. Perspectives on Language and Literacy. 2006;32(3):31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoon MB. Delivering reading instruction to adolescent struggling readers using two versions of the Reading Achievement Multi-component Program (RAMP-UP): Does modality matter. 2013 Manuscript is progress. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoon MB, Sandow A, Hunter V. Re-organizing the instructional reading components: Could there be a better way to modality remedial reading programs to maximize middle school students with reading disabilities’ response to treatment? Annals of Dyslexia. 2010;60:57–85. doi: 10.1007/s11881-009-0033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnine DW, Silbert J, Kameenui EJ. Direct instruction reading. 3. Colombus, OH: Merrill Publishing Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chard DJ, Osborn J. Phonics and word recognition and instruction in early reading programs: Guidelines for accessibility. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 1999;14(2):107–117. doi: 10.1207/sldrp1402_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M. Adolescents who struggle with word identification: Research and practice. In: Jetton T, Dole J, editors. Adolescent literacy research and practice. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis ME, Longo AM. When adolescents can’t read: Methods and materials that work. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting LE, Scarborough HS. Prediction of reading comprehension: Relative contributions of word recognition, language proficiency, and other cognitive skills can depend on how comprehension is measured. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2006;10(3):277–299. [Google Scholar]

- Dole JA, Duffy GG, Roehler LR, Pearson PD. Moveing from the olde to the new: Research on reading comprehension instruction. Review of Educational Research. 1991;61(2):239–264. doi: 10.3102/00346543061002239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dowhower SL. Repeated reading revisited: Research into practice. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Disabilities. 1994;10:343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds MS, Vaughn S, Wexler J, Reutebuch C, Cable A, Tackett KK, Schnakenberg JW. A synthesis of reading interventions and effects on reading comprehension outcomes for older struggling readers. Review of Educational Research. 2009;79:262–300. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC. Reconceptualizing the development of sight word reading and its relationship to recoding. In: Gough PB, Ehri LC, Treiman R, editors. Reading acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 107–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC. Learning to read and learning to spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorders. 2000;20(3):19036. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Shaywitz SE, Shankweiler DP, Katz L, Lieberman LY, Stuebing KK, Francis DJ, et al. Cognitive profiles of reading disabilities: Comparisons of discrepancy and low achievement definitions. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Denton CA, Fuchs LS, Vaughn SR. Multi-tiered reading instruction: Linking general education and special education. In: Gilger J, Richardson S, editors. Research-based education and intervention: What we need to know. Baltimore, MD: International Dyslexia Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Kazdan S. Effects of peer-assisted learning strategies on high school students with serious reading problems. Remedial and Special Education. 1999;20(5):309–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbring TS, Goin LI. Literacy instruction for older struggling readers: What is the role of technology? Reading &Writing Quarterly. 2004;20(2):123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hock MF, Brasseur IF, Deshler DD, Catts HW, Marquis J, Mark CA, Stribling JW. / What is the reading component skill profile of adolescent struggling readers in urban schools? Learning Disability Quarterly. 2009;32:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Juel C, Roper/Schneider D. The influence of basal readers on first grade reading. Reading Research Quarterly. 1985;20(2):134–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman ME, Apel K. Effects of a multiple linguistic and prescriptive approach to spelling instruction: A case study. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2004;25(2):56–66. [Google Scholar]

- King LA, King DW, McArdle JJ, Saxe GN, Doron-LaMarca S, Orazem RJ. Latent difference score approach to longitudinal trauma research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:771–785. doi: 10.1002/jts.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBerge D, Samuels SJ. Toward a theory of automatic processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology. 1974;6:293–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett MW, Borden SL, DeLuca T, Lacerenza L, Benson NJ, Brackstone D. Treating the core deficits of developmental dyslexia: Evidence of transfer of learning after phononlogically- and strategy- based reading training programs. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(6):805–822. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett MW, Lacerenza L, Borden SL, Frijters JC, Steinbach KA, De Palma M. Components of effective remediation for developmental reading disabilities: Combining phonological and strategy-based instruction to improve outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92(2):263–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett MW, Steinbach KA. The effectiveness of remedial programs for reading disabled children of different ages: Does the benefit decrease for older children? Learning Disability Quarterly. 1997;20:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett MW, Steinbach KA, Frijters JC. Remediating the core deficits of developmental reading disability: A double-deficit perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2000;33(4):334–358. doi: 10.1177/002221940003300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson JJ, Crede LA. Learning to spell: Implications for assessment and intervention. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1999;30:243–254. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461.3003.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE, Bakken JP, Whedon C. Reading comprehension: A synthesis of research in learning disabilities. In: Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, editors. Advances in learning and behavioral disabilities. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1996. pp. 277–303. [Google Scholar]

- Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE, Mohler LJ, Beranek ML, Spencer V, Boon RT, et al. Can middle school students with serious reading difficulties help each other and learn anything? Learning Disabilities: Research and Practice. 2001;16(1):18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes PG, Howard JK, Allen SH, Fuchs D. Peer-assisted learning strategies for first-grade readers: Responding to the needs of diverse learners. Reading Research Quarterly. 1998;33(1):62–94. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.33.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. A latent difference score approach to longitudinal dynamic structural analyses. In: Cudeck R, du Toit S, Sorbom D, editors. Structural Equation Modeling: Present and Future. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. pp. 342–380. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, Foorman BR, Branum-Martin L, Taylor WP. Literacy as a unidimensional multilevel construct: Validation, sources of influence, and implications in a longitudinal study in grades 1–4. Scientific Study of Reading. 2005;9(2):85–116. [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D. Cognitive Behaviour Modification. Scandinavian Journal Behaviour \ Therapy. 1977;6(4):185–192. doi: 10.1080/16506073.1977.9626708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nation K, Snowling JJ, Clarke P. Dissecting the relationship between language skills and learning to read: Semantic and phonological contribution to new vocabulary learning children with poor reading comprehension. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology. 2000;9:131–139. [Google Scholar]

- National Reading Panel (NRP)—Report of the Subgroups. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2000. (NIH Pub. No. 004754) [Google Scholar]

- Olson RK, Wise B, Ring J, Johnson M. Computer-based remedial training in phoneme awareness and phonological decoding: Effects on the posttraining development of word recognition. Scientific Studies of Reading. 1997;1(3):235–254. [Google Scholar]

- RAND Reading Study Group. Reading for understanding; Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2002. Retrieved August, 2007, from http://www.rand.org/multi/achievementforall/reading/readreport.html. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RE. Attentional resource emancipation: Toward understanding the interaction of word identification and comprehension processes in reading. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2000;4(3):169–95. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Torgesen JK, Boardman A, Scammacca N. Evidence-based strategies for reading instruction of older students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2008;23(2):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini JP. Efficiency in word reading of adults: Ability group comparisons. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2002;6(3):267–298. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels SJ, Kamil ML. Models of the reading process. In: Pearson PD, Barr R, Kamil ML, Mosenthal P, editors. Handbook of reading research. New York: Longman; 1984. pp. 185–224. [Google Scholar]

- Savage J. Sound it out! Phonics in a comprehensive reading system. Columbus, OH: Open University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough H, Sabatini JP, Shore J, Cutting LE, Pugh K, Katz L. Meaningful Reading Gains by Adult Literacy Learner this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Shankweiler D, Lundquist E. On the relations between learning to spell and learning to read. In: Frost R, Katz L, editors. Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning. North Holland: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1992. pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn MM, Shinn MR. AIMSweb Training Workbook: Administration and Scoring of Reading Curriculum-Based Measurement (R-CBM) for Use in General Outcome Measurement. NCS Pearson Assessment 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE, Siegel LS. Phenotypic performance profile of children with reading disabilities: A regression-based test of the phonological-core variable-difference model. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:24–53. [Google Scholar]

- Suggate SP. Why what we teach depends on when: Grade and reading intervention modality moderate effect size. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1556–1579. doi: 10.1037/a0020612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL. Instructional components that predict treatment outcomes for students with learning disabilities: Support for a combined strategy and direct instruction model. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 1999a;14(3):129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL. Reading research for students with LD: A meta-analysis of intervention outcomes. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1999b;32:504–532. doi: 10.1177/002221949903200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL. Research on interventions for adolescents with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of outcomes related to higher-order processing. The Elementary School Journal. 2001;101(3):331–348. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL, Hoskyn M. Experimental intervention research on students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of treatment outcomes. Review of Educational Research. 1998;68(3):277–321. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL, Hoskyn M, Lee C. Interventions for students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL, Trainin G, Necoechea DM, Hammill DD. Rapid naming, phonological awareness, and reading: A meta-analysis of the correlation evidence. Review of Educational Research. 2003;73(4):407–440. [Google Scholar]

- Talbott E, Lloyd JW, Tankersley M. Effects of reading comprehension interventions for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly. 1994;17:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton S. Using the spelling/meaning connection to develop word knowledge in older students. Journal of Reading. 1983;27(1):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Houston DD, Rissman LM, Decker SM, Roberts G, Vaughn S, et al. Academic literacy instruction for adolescents: A guidance document form the center on instruction. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Bos CS. Strategies for teaching students with learning and behavior problems. Pearson; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Chard DJ, Bryant DP, Coleman M, Tyler B-J, Linan-Thompson S, et al. Fluency and comprehension interventions for third-grade students. Remedial and Special Education. 2000;21(6):321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Crinio PT, Wanzek J, Wexler J, Fletcher JM, Denton CD, Berth A, Romain M, Francis DJ. Response to intervention for middle school struggling readers: Effects of a primary and secondary intervention. School Psychology Review. 2010;31:2–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Denton CA, Fletcher JM. Why intensive interventions are necessary for students with severe reading difficulties. Psychology for the Schools. 2010;47(5):432–444. doi: 10.1002/pits.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wexler J, Leroux A, Roberts G, Denton C, Barth A, Fletcher J. Effects of intensive reading intervention for eighth-grade students with persistently inadequate response to intervention. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2011a doi: 10.1177/0022219411402692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wexler J, Roberts G, Bart A, Cirino PT, Romain MA, Francia D, Fletcher J, Denton CA. Effect of individualized and standardized interventions on middles school students with reading disabilities. Exceptional Children. 2011b;77(4):391–407. doi: 10.1177/001440291107700401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Tunmer WE, Jaccard JJ, Chen R. Components of reading ability: Multivariate evidence for a convergent skills model of reading development. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2007;11:3–32. doi: 10.1080/10888430709336632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt JL, Blalock G. Gray silent reading test. Austin: Pro-Ed; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson tests of achievement. 3. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 2001. [Google Scholar]